Is Co-Creation Always Sustainable? Empirical Exploration of Co-Creation Patterns, Practices, and Outcomes in Bottom of the Pyramid Markets

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Co-Creation and its Operationalization in BOP Markets

2.2. Social Value and Economic Necessity of Co-Creation at the BOP

2.3. Research Gap

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

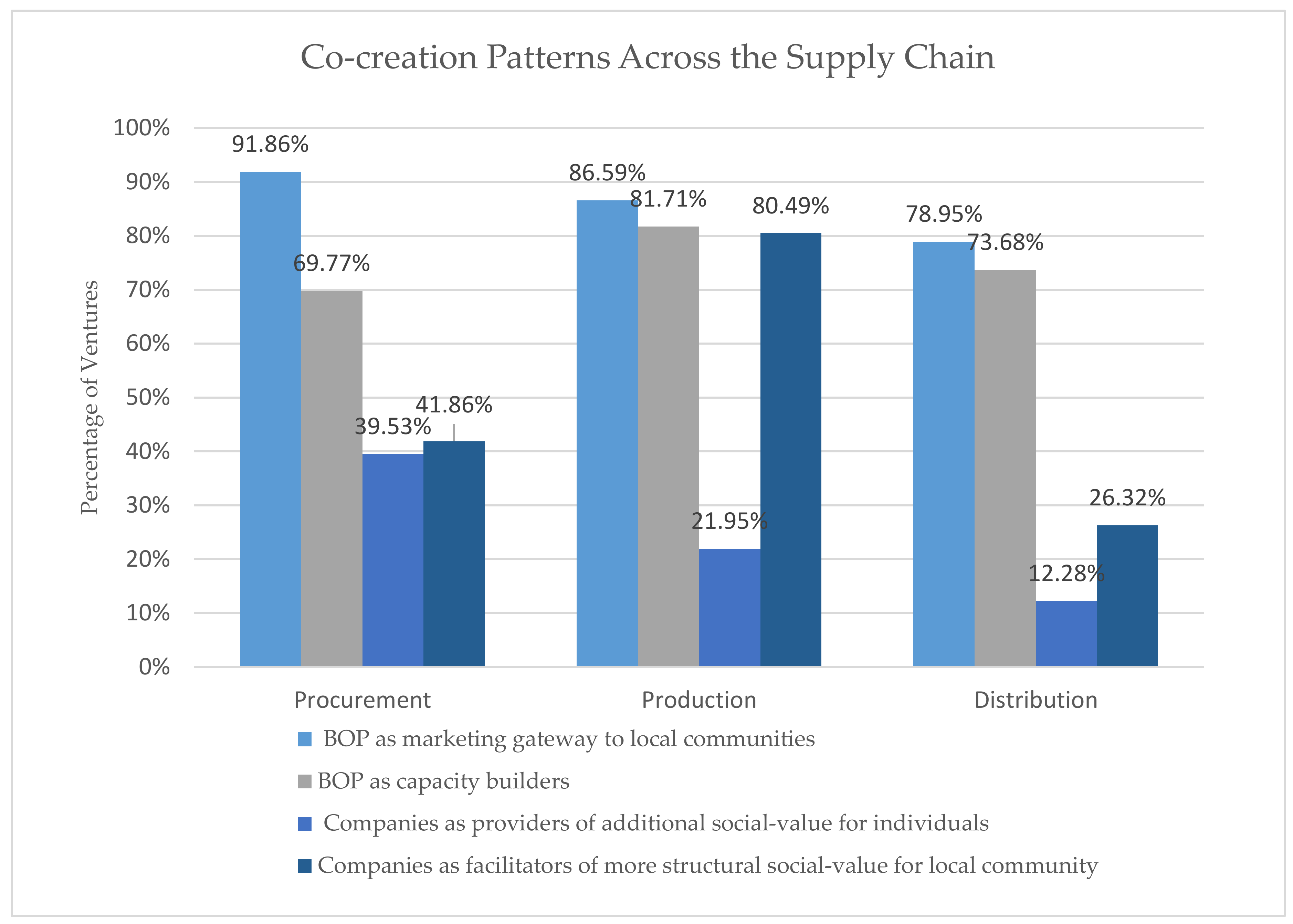

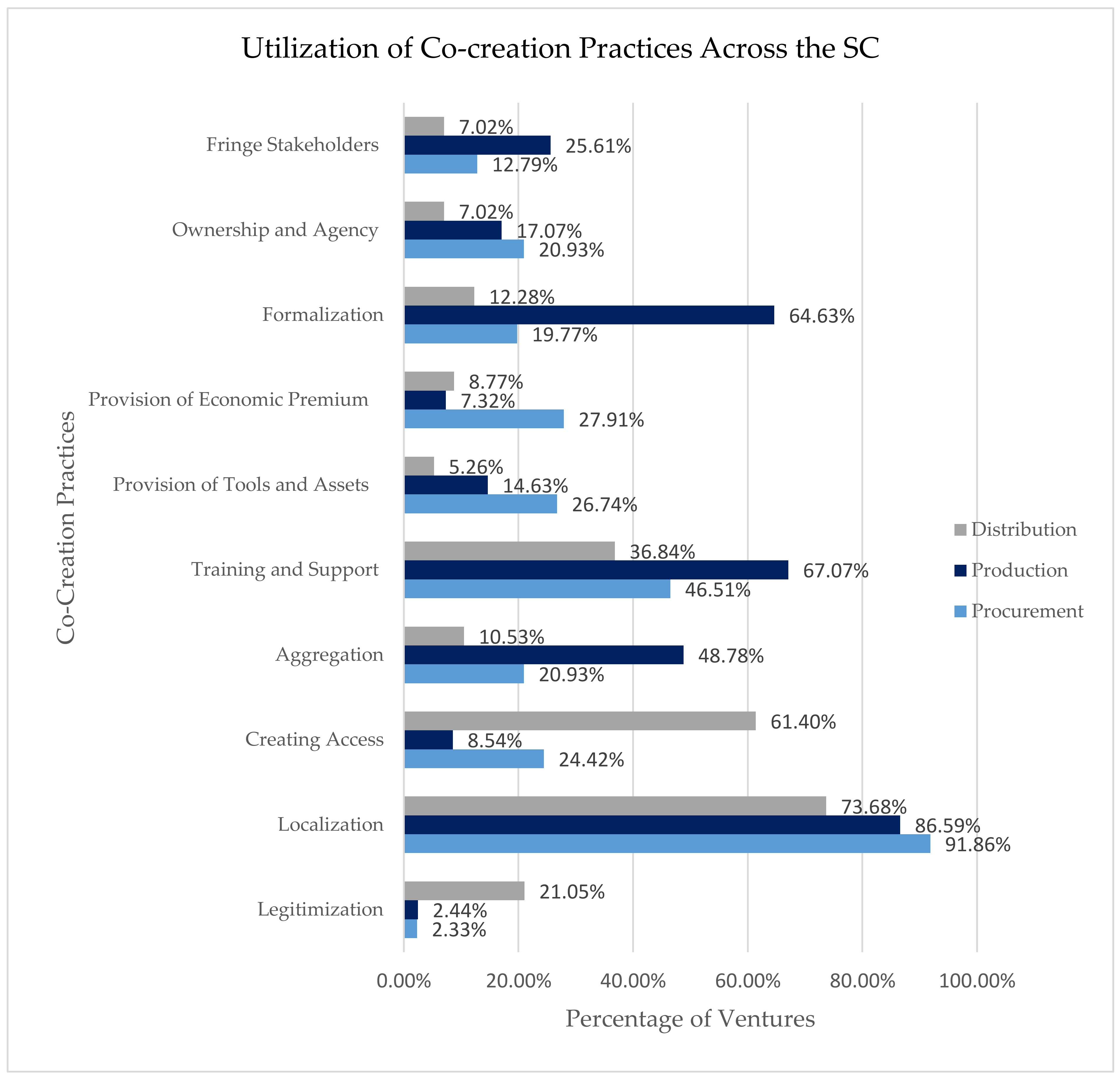

4.1. BOP as a Marketing Gateway to Local Communities

4.2. BOP as Capacity Builders

4.3. Companies as Providers of Additional Social Value for Individuals

4.4. Companies as Facilitators of More Structural Social Value for Local Communities

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Case Name | Video | Social Media | Official Website | Company Reports | Other (ex. Additional Websites, SEED in Depth Case-Study Series) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 Star Stoves | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 14 |

| Alternative Energy Source for Heating | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Amazóniko | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Asrat and Helawi Engineering | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Awamu Biomass Energy Ltd. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| Bringing gas nearer to people | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 11 |

| EcoBrick Exchange | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Ekasi Energy | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Electricity4all | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Energy Unlimited | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Frontier Markets: Last Mile Distribution for Solar | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Ghana Bamboo Bikes Initiative | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Gogle Energy Saving Stoves and Engineering | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| GreenTech Company Ltd - fuel briquettes from groundnut shells combined with fuel efficient stoves | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| JITA Social Business Bangladesh Ltd. | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| KARIBU Solar Power | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 13 |

| Khainza Energy Limited | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Khoelife Organic Soap and Oils Primary Co-operative | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Kumudzi Kuwale | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| L’s solution ltd | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Lagazel | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| Lighting Up Women’s Lives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Loja de Energias | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Magiro Hydro Electric Limited (MHEL) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| MakaaZingira | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Man and Man Enterprise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Mozambikes | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Nafore and Afrisolar Energy Kiosks | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Nuru Energy | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| One Million Rural Cisterns | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Papyrus Reeds, Our Future Hope | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Pollinate Energy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Powering the Future with SuryaHurricanes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| PROVOKAME | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| RECAPO CBO | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| RISE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| RK Renew Energy PLC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Sahelia Solar | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Solanterns: Replacing 1 Million Kerosene Lanterns with 1 Million Solar Lanterns | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Solar Bread Oven | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Solar Serve | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 10 |

| Solar Sister – African women led grassroots green energy revolution | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| SolarTurtle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| SPOUTS of Water | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| STM Solar Technologies Manufacturing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Sunny Money | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 22 |

| Sustaintech India Pvt. Ltd. | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Switch ON- ONergy | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| Village Energy | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 9 |

| Waste Ventures India | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| A Global Marketing Partnership for SRI Indigenous Rice | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Agroforestry for sustainable land use and economic empowerment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Agua Para Todos/Water for All | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| All Women Recycling | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 8 |

| ALMODO | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| Appropriate Energy saving Technologies LTD | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Arusha Women Entrepreneur | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Au Grain de Sésame | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Backpack Farm Agriculture Program | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Baobab Products Mozambique | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Belle Verte Ltée | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Black Gold Farm Manure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Botanic Treasures | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Brent Technologies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| Chonona Aquaculture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| City Waste Recycling | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Claire Reid Reel Gardening | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| COMSOL Cooperative for Environmental Solutions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Coopérative Sahel Vert | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Cows to Kilowatts | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| Dagoretti Market Biogas Latrine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Daily Dump (PBK Waste Solutions Private Limited) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 8 |

| Days for Girls Uganda | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| DeCo!—Decentralized Composting for Sustainable Farming and Development | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Diseclar: Ecological design and production | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Duncan Village Secondary Recycling Cooperative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| East Africa Fruit Farm and Company | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Eco-Amazon Piabas of Rio Negro | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Eco-Shoes | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| EcoAct Tanzania | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| EcoPost—Fencing Posts from Recycled Post-Consumer Waste Plastic | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| G-lish: Income Generation, Re-Generation, Next Generation | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| Gorilla Conservation Coffee | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Green Acre Living | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Green Bio Energy | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Green Heat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Green Organic Watch Cocoa Project | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Green Road | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Green the Map | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| greenABLE | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Growing the Future | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| High Atlas Agriculture | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Horizon Business Ventures Limited | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Hortinet | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| ICOSEED Enterprises | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Imai Farming Cooperative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| KadAfrica: Girls Agro Investment (GAIN) Project | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Karama | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Kataara Women’s Poverty Alleviation Group | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Kencoco Limited | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| KingFire Briquettes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Kisumu Innovation Center | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| KOLCAFÉ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Life Out Of Plastic—L.O.O.P. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Linking Small-Scale Farmers to Input-Output Markets through Rural Enterprise Network (REN) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Mashandilo Co-operative | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Masole Ammele | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Masupa Enterprises | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Mesula—Meru Sustainable Land Ltd. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| New Life | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| O Viveiro | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Organic Farm Inputs and Farm Produce—(KOFAr Ltd) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| ORIBAGS INNOVATIONS (U) LTD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| P.E.A.C.E.—Thinana Recycling Cooperative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| People of the Sun | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| Piratas do Pau Upcycling Centre | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Plastic Waste Recycling as an Alternative to Burning and Landfilling | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Precious Life Foundation’s Outgrower Project | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Pumpkin Value Addition Enterprise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| RECFAM—PRIDE Pads | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Recycling Centre for Used Plastic Bags | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Recycling for Environmental Recovery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Resentse Sinqobile Trust Trading (Zondi BuyBack Initiative) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Safi Organics | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| SEPALI—community based silk producers association | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| TECOCARRE | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Terra Nova Waste to Farming | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| The Shea Economic Empowerment Program (SEEP) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Tii Ki Komi Cassava Commercial Growers (TCCG) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Unique Quality Product Enterprise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Village Cereal Aggregation Centres (VCAC) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Walali Company Limited | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| WASHKing | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Waste to Food | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Women’s Off-season Vegetable Production Group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 47 | 32 | 146 | 1 | 386 | 612 |

References

- Karamchandani, A.; Kubzansky, M.; Lalwani, N. The Globe—Is the Bottom of the Pyramid Really for you? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/03/the-globe-is-the-bottom-of-the-pyramid-really-for-you (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Rangan, V.K.; Chu, M.; Petkoski, D. The Globe—Segmenting the base of the pyramid. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/06/the-globe-segmenting-the-base-of-the-pyramid (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Carleton, T.A. Crop-damaging temperatures increase suicide rates in India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8746–8751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Matos, S. Incorporating impoverished communities in sustainable supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. Environmental Supply Chain Innovation. In Greening the Supply Chain; Sarkis, J., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, J.D.; Klassen, R.; Jayaraman, V. Sustainable supply chains: An introduction. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Hahn, R.; Seuring, S. Sustainable supply chain management in “Base of the Pyramid” food projects—A path to triple bottom line approaches for multinationals? Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S. Socially responsible supply chains in emerging markets: Some research opportunities. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C.S. Supply chain opportunities at the bottom of the pyramid. Decision 2016, 43, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalid, R.U.; Seuring, S.; Beske, P.; Land, A.; Yawar, S.A.; Wagner, R. Putting sustainable supply chain management into base of the pyramid research. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahi, T. Cocreation at the Base of the Pyramid. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 416–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollakota, K.; Gupta, V.; Bork, J.T. Reaching customers at the base of the pyramid-a two-stage business strategy. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 52, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, A. The Mirage of Marketing to the Bottom of the Pyramid: How the Private Sector Can Help Alleviate Poverty. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 49, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachani, S.; Smith, N.C. Socially Responsible Distribution: Distribution Strategies for Reaching the Bottom of the Pyramid. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 50, 52–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Bendul, J.C. Value chain integration of base of the pyramid consumers: An empirical study of drivers and performance outcomes. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T.; Anupindi, R.; Sheth, S. Creating mutual value: Lessons learned from ventures serving base of the pyramid producers. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Munir, K.; Gregg, T. Impact at the ‘Bottom of the Pyramid’: The Role of Social Capital in Capability Development and Community Empowerment. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 813–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanis, E.; Milstein, M. Back to Business Fundamentals: Making. Bottom of the Pyramid. Relevant to Core Business. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2012, (Special Issue 4). Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/1581 (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Khan, R. How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendul, J.C.; Rosca, E.; Pivovarova, D. Sustainable Supply Chain Models For Base Of The Pyramid. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, S107–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Romijn, H. The empty rhetoric of poverty reduction at the base of the pyramid. Organization 2011, 19, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grönroos, C. Service logic revisited: Who creates value? And who co-creates? Eur. Bus. Rev. 2008, 20, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Voima, P. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2013, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, K.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, V. What Drives the customer Of World’s Largest Market To Participate In Value Co-Creation? Market. Intel. Plan. 2013, 32, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.L.; Pandit, A.; Saren, M.; Bhowmick, S.; Woodruffe-Burton, H. Co-creation of value at the bottom of the pyramid: Analysing Bangladeshi farmers’ use of mobile telephony. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn, R.; Berg, N. The Gatekeeping Function of Trust in Cross-sector Social Partnerships. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2014, 119, 385–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Rivera-Santos, M.; Rufín, C. Reviewing A Decade of research on the “Base/Bottom of the Pyramid” (BOP) Concept. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 338–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanis, E.; Hart, S. Innovation from the inside out. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2009, 50, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Santos, M.; Rufín, C. Global village vs. small town: Understanding networks at the Base of the Pyramid. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; McKague, K.; Thomson, J.; Davies, R.; Medalye, J.; Prada, M. Creating sustainable local enterprise networks. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, C.; Johnstone-Louis, M.; Scott, L. Shampoo, saris and SIM cards: Seeking entrepreneurial futures at the bottom of the pyramid. Gend. Dev. 2012, 20, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K. The Fortune at the Bottom or the Middle of the Pyramid? Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2008, 3, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, V.; Rosca, E. Driving impact through base of the pyramid distribution models: The role of intermediary organizations. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 492–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, K. Cannibalizing the Informal Economy: Frugal Innovation and Economic Inclusion in Africa. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2018, 30, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, N.M.; Doh, J.P.; Oetzel, J.; Yaziji, M. Corporate-NGO Collaboration: Co-creating New Business Models for Developing Markets. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hart, S.L. The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Strateg. Bus. 2002, 26, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; London, T. Developing Native Capability What Multinational Corporations Can Learn from the Base of the Pyramid. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. 2005. Available online: https://www.stuartlhart.com/sites/stuartlhart.com/files/2005SU_feature_hart.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2019).

- Amartya, S. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shivarajan, S.; Srinivasan, A. The Poor as Suppliers of Intellectual Property: A Social Network Approach to Sustainable Poverty Alleviation. Bus. Ethic Q. 2013, 23, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplinsky, R. Bottom of the Pyramid Innovation and Pro Poor Growth. Ebook. PRMED Division of the World Bank. 2011. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/26796/703720WP0P12450Poor0Growth00Sept011.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Pansera, M. Frugal or Fair? The Unfulfilled Promises of Frugal Innovation. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2018, 8, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esko, S.; Zeromskis, M.; Hsuan, J. Value chain and innovation at the base of the pyramid. South Asian J. Glob. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, P.; Ricart, J.E. Business model innovation and sources of value creation in low-income markets. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, A.; Michelini, L.; Martignoni, G. Frugal approach to innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T. The base-of-the-pyramid perspective: A new approach to poverty alleviation. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- SEED Awards. SEED—Promoting Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development. 2019. Available online: https://www.seed.uno/programmes/enterprise-support/awards (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, R.; van Beers, C.; Doorn, N. Value capture and value creation: The role of information technology in business models for frugal innovations in Africa. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 131, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gap. | Selected Examples of Concerns Raised in Literature |

|---|---|

| Nuanced understanding of the operationalization of the co-creation principle: i.e., how can companies co-create with the BOP in practice? | “[…] there is a need to examine how these [co-creation] programs are operationalized so that we can gain a deeper understanding about the impact of these programs on the society at large” [10] (p. 9). “Unfortunately, there are to date no empirical BOP studies that focus on cocreation, and we know little about the processes or methods of cocreation at the BOP” [13] (p. 427). “Thus, while the recent discourse on social exclusion and BOP has identified participation of impoverished communities within modern supply chains as a solution to poverty, little is known about how this can occur” [4] (p. 127). |

| Gap. | Selected Examples of Concerns Raised in Literature |

|---|---|

| Deeper understanding of the social impact and economic necessity of co-creation: i.e., does co-creation always facilitate increased social and economic value for both parties? | “[…] when it comes to business implementation strategy, there is a myopic focus on the consumer engagement process. Going native, immersing oneself in the local culture and social structure, building trust through dialogue and mutual exchange, and then co-creating the offering in close partnership with BOP consumers are presented as virtual cure-alls to the business challenge of BOP markets” [20] (p.84). “While consumer engagement is, without question, a valuable tool for addressing certain business challenges, the field’s captivation with co-creation is distracting companies from the key issues that impact success” [20] (p.87). “[…] yet there remain major problems with these wider participatory schemes [….] such social concerns are emerging as the key challenge in sustainable supply chains, yet remain poorly understood” [4] (p. 125). “Moreover, trade-offs between cost effectiveness and impact provide further evidence for the difficulties encountered by firms to include BoP in supply chains as active economic value creators” [36] (p. 509). “Since significant firm investments are required to engage BOP consumers in value chain activities, it is essential to examine the potential value of BOP consumer integration” [17] (p. 163). |

| Example Codes | Second Order Categories: Supply Chain Practices | First Order Categories: Co-Creation Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| elder/community elders/business owner/shop owner/existing businesses/church/word of mouth/leaders/demonstrations/graduates/dialogue/ambassadors | Legitimization | BOP as marketing gateway to local communities |

| locally procure/indigenous/traditional/artisanal/local production/locally produce/local skills/artisan/mason/crafts/artisans/time-honored techniques/door to door/hyper-local | Localization | |

| Local sales-agent/micro-entrepreneur/village level entrepreneurs/commission-based/indirect employment/micro-franchisee/franchise/additional source of income/micro-entrepreneurs/collectors/part-time/indirect jobs/additional source of income | Creating Access | BOP as capacity builders |

| peer group/bulk/centralization/aggregation/centralized demand/drop-off points/collection-points/women group/youth group/pool resources/self-managed groups/community groups/self-organizing/collection yards/collection centers/savings groups | Aggregation | |

| monitor/guide/mentor/support/consult/guide/train/develop/know-how | Training and Support | |

| certification/provide inputs/provide land/micro credit/micro loans/micro-finance/low-interest/no interest/loans/micro-savings/social lending/health insurance/scholarships/on site housing/market linkages/on-site childcare | Provision of Tools or Assets | Companies as providers of additional social value for individuals |

| fair prices/premium prices/fair market value/above market value/above market wage/export/premium quality/high quality/gourmet/niche/organic/export/niche/premium/upcycling/tourist/boutique/organic | Provision of Economic Premium | |

| local employees/full-time employees/direct employment/regular income/directly employed/formalized/full-employment | Formalization | Companies as facilitators of more structural social value for local community |

| independently-owned/women-owned/ micro-business/micro-cooperatives/cooperatives/community-owned/local-ownership/women-owned/woman-led/cooperative | Ownership and Agency | |

| unemployed/youth/marginalized/mothers/school-dropouts/seasonal workers/disadvantaged/vulnerable/illiterate/disabled/refugees/ex-combatants/HIV/mothers/marginalized/disabilities/underprivileged | Focus on Fringe Stakeholders |

| Co-Creation Pattern. | Sustainability Outcomes of Co-Creation | Operationalization of Co-Creation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Value for BOP Individuals | Economic Necessity for Ventures | Co-Creation Practices | Implementation Example Upstream the SC | Implementation Example Downstream the SC | |

| BOP as a marketing gateway to local communities | Decreased or Neutral | Significantly Necessary | Legitimization | Promoting awareness of venture’s cause through brand ambassadors | Marketing through word of mouth marketing, repertoire and trust building through key figures in community |

| Localization | Local sourcing, integration of local know-how in production (e.g., specialized artisanal techniques) | Ensuring hyper-local consumption of goods | |||

| Co-Creation Pattern. | Sustainability Outcomes of Co-Creation | Operationalization of Co-Creation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Value for BOP Individuals | Economic Necessity for Ventures | Specific Supply Chain Practices | Implementation Examples Upstream | Implementation Examples Downstream | |

| BOP as capacity builders | Neutral or Slightly Increased | Necessary | Creating Access | Building a network of small scale suppliers (e.g., small-holder farmer) or working with existing networks (e.g., collectors) | Building a network of small scale BOP distributors |

| Aggregation | Utilizing standard, agreed upon drop off points for potential small scale suppliers to sell raw material | Working with consumer peer groups, church groups, self-organized groups | |||

| Training and Support | Training in new skills such as sustainable farming, semi-automated manufacturing, and machinery maintenance | Supporting in administrative task such as opening a bank account, training in book-keeping | |||

| Co-Creation Pattern | Sustainability Outcomes of Co-Creation | Operationalization of Co-Creation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Value for BOP Individuals | Economic Necessity for Ventures | Specific Supply Chain Practices | Implementation Examples Upstream | Implementation Examples Downstream | |

| Companies as providers of additional social value for individuals | Increased | Somewhat necessary | Provision of Tools or Assets | Provision of child-care for female employees, scholarships for vocational school, healthcare, access to higher quality inputs, lending land | Providing certificate, Microfinancing, or connection to fair organizations providing microfinancing for initial investments into franchise/new business |

| Provision of Economic Premium | Paying above market prices for inputs | Providing support and linkage to more lucrative markets | |||

| Co-Creation Pattern. | Sustainability Outcomes of Co-Creation | Operationalization of Co-Creation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Value for BOP Individuals | Economic Necessity for Ventures | Specific Supply Chain Practices | Implementation Examples Upstream | Implementation Examples Downstream | |

| Companies as facilitators of more structural social value for local communities | Significantly Increased | Not necessary | Formalization | Full employment as manufacturing employees, formalizing positions of waste-collectors by coordination through an online app, and ensuring regular payment | Direct employment through kiosk or hub model |

| Ownership and Agency | Creation or encouragement of cooperatives or microcooperatives | Building new businesses, women led or owned businesses | |||

| Focus on Fringe Stakeholders | Integration of wide range of marginalized stakeholders in production, focus on sourcing from individuals who have seasonal employment | Primarily through focusing on creating decentralized distribution networks with women | |||

| Operationalization of Co-Creation. | Social and Economic Outcomes of Co-Creation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Creation Pattern | Co-Creation Practices | Social Value for BOP Individuals | Economic Necessity for Ventures |

| BOP as marketing gateway to local communities | Legitimization | Decreased or Neutral | Significantly Necessary |

| Localization | |||

| BOP as capacity builders | Creating Access | Neutral or Slightly Increased | Necessary |

| Aggregation | |||

| Training and Support | |||

| Companies as providers of additional social value for individuals | Provision of Tools or Assets | Increased | Somewhat necessary |

| Provision of Economic Premium | |||

| Companies as facilitators of more structural social value for local communities | Formalization | Significantly Increased | Not necessary |

| Ownership and Agency | |||

| Focus on Fringe Stakeholders | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knizkov, S.; Arlinghaus, J.C. Is Co-Creation Always Sustainable? Empirical Exploration of Co-Creation Patterns, Practices, and Outcomes in Bottom of the Pyramid Markets. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6017. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216017

Knizkov S, Arlinghaus JC. Is Co-Creation Always Sustainable? Empirical Exploration of Co-Creation Patterns, Practices, and Outcomes in Bottom of the Pyramid Markets. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):6017. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216017

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnizkov, Stephanie, and Julia C. Arlinghaus. 2019. "Is Co-Creation Always Sustainable? Empirical Exploration of Co-Creation Patterns, Practices, and Outcomes in Bottom of the Pyramid Markets" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 6017. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216017