Research on Field Reconstruction and Community Design of Living Settlements—An Example of Repairing a Fish Stove in the Hua-Zhai Settlement on Wang-An Island, Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

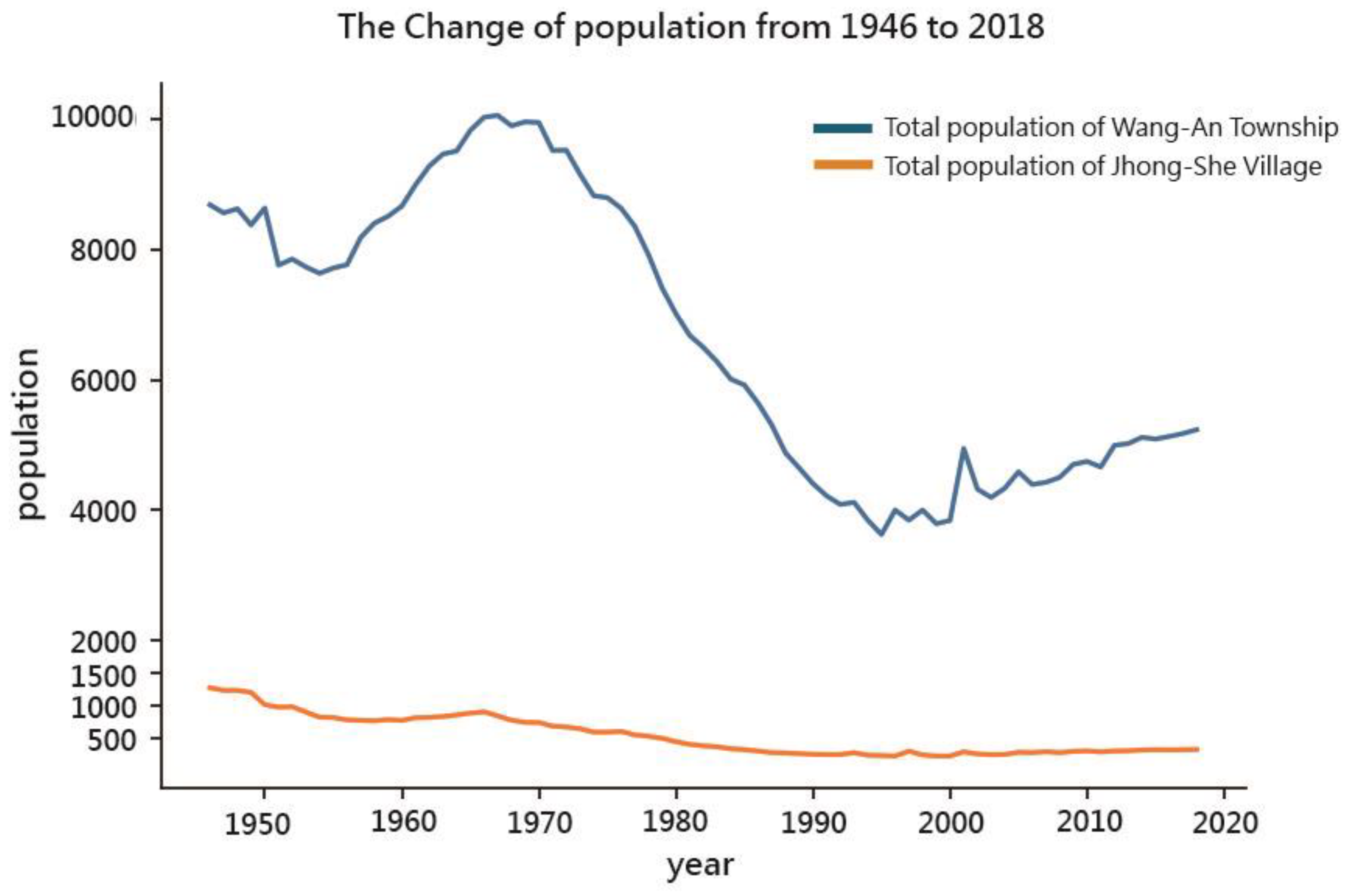

1.1. Settlement Dilemma: The Aging of the Population, the Loss of the Population, and the Innocence of Important Settlements

1.2. Experiences in the Overall Construction of the Community: Internal Conflicts in Settlements, Unclear Awareness of Settlements, and Inadequate Government Notification Mechanisms

1.3. Hua-Zhai Fish Stove

2. Literature Review

2.1. Field of Living Settlement

2.2. Community Design: The Development History of Overall Community Construction in Taiwan

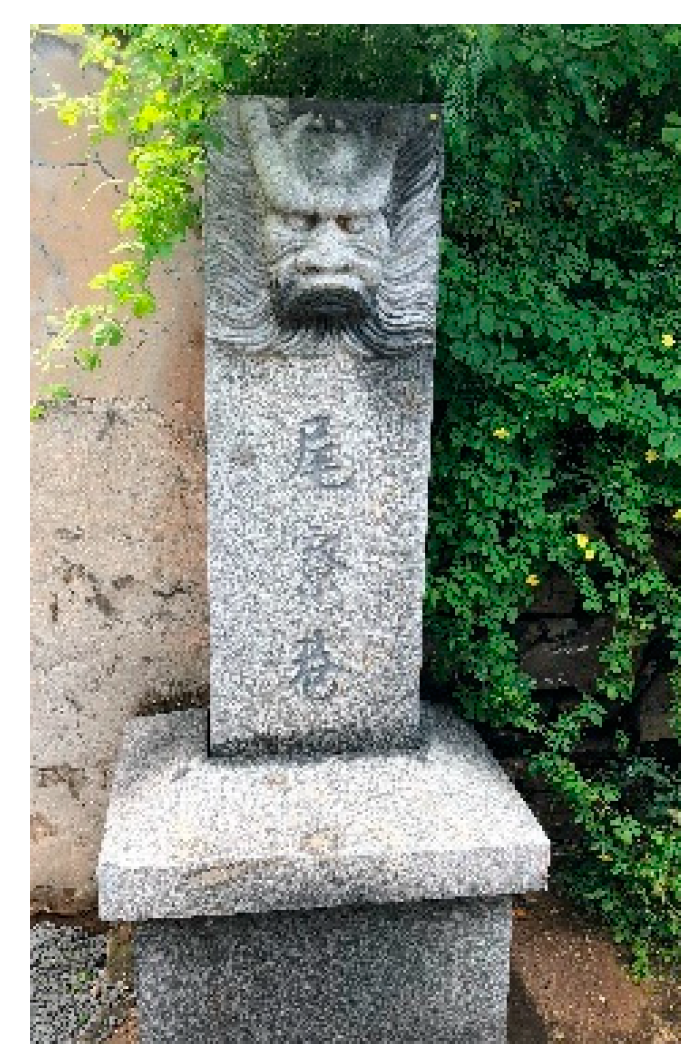

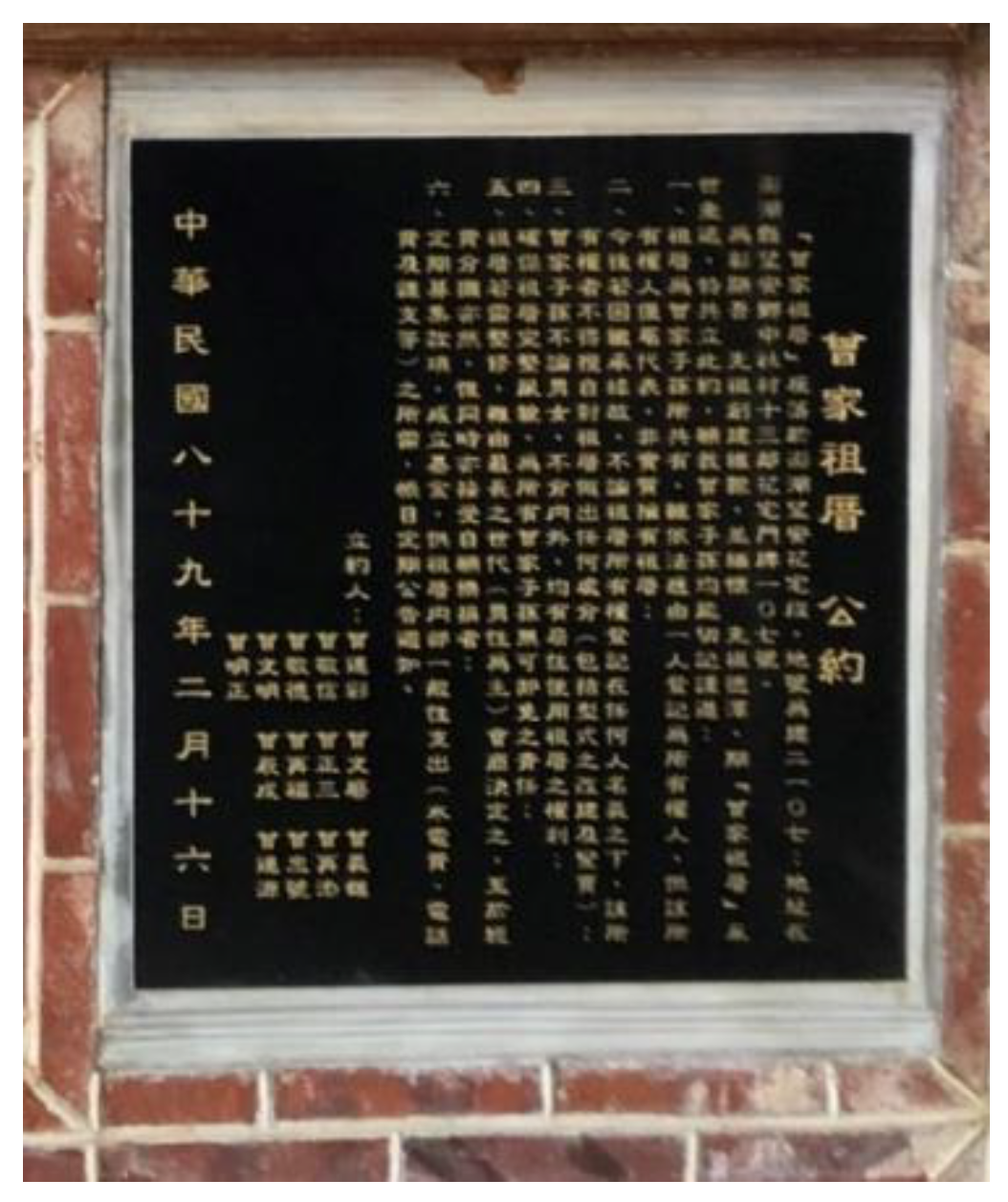

2.3. Important Settlement Construction: The Values of the Hua-Zhai Settlement as a Cultural Asset

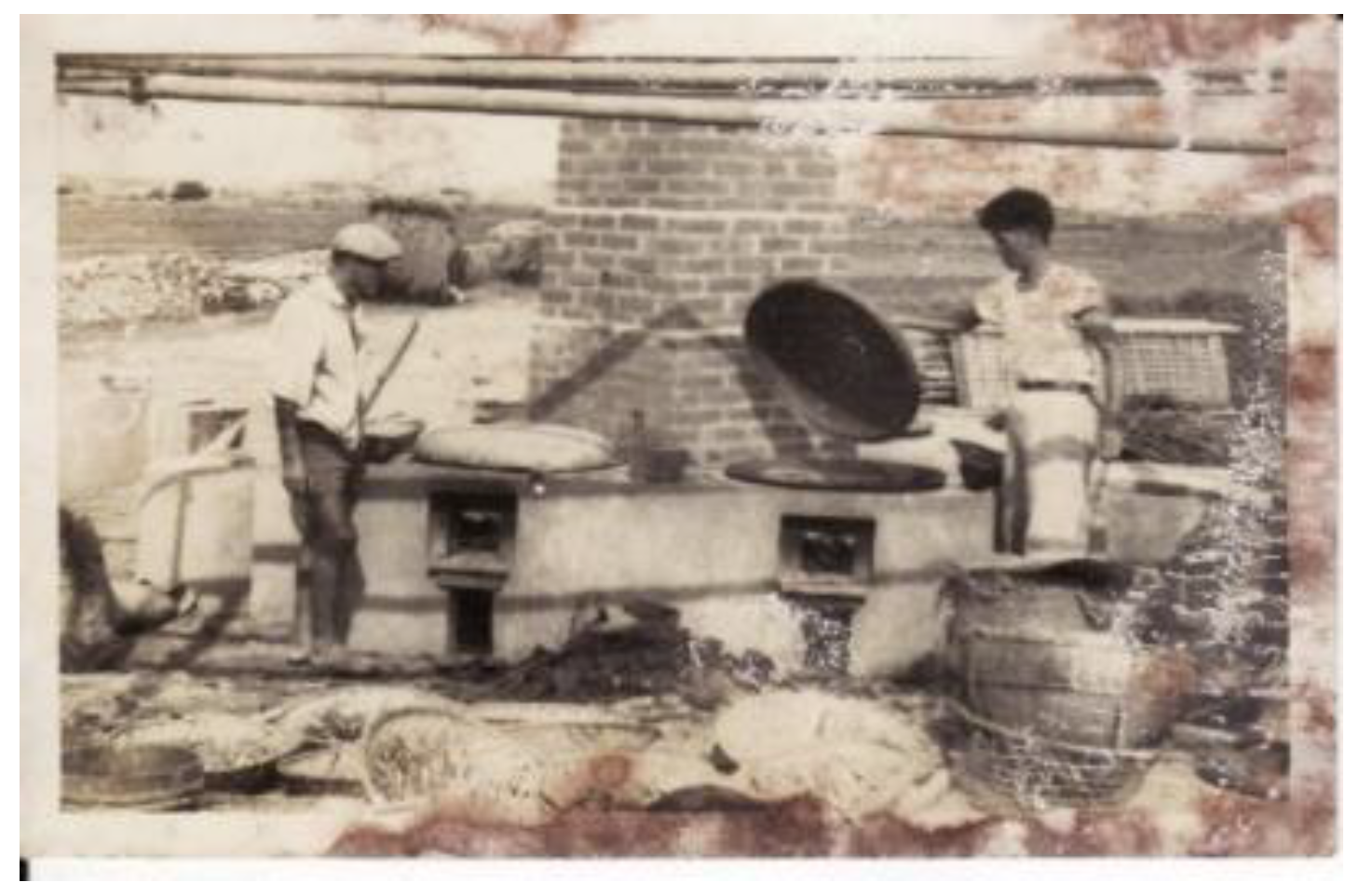

2.4. Peng-Hu Fish Stoves and the Fishery Processing Industry

3. Research Methods

4. Fish Stove Restoration Case Study

4.1. The Beginning of Hua-Zhai Activation—Descriptions of Actions in the Past Few Years

4.1.1. The Entrusted Execution Project of the Peng-Hu County Government Cultural Bureau

- Establish the Network

- Hua-Zhai management and maintenance service center: internally based on the exchange of residents’ services; externally based on providing accurate information about the history and culture of the settlement.

- Facebook fan page: mainly based on reporting the relevant news, activities, and messages of Hua-Zhai.

- Community services: clean and re-cultivate Caizhai (vegetable farms with coral stone fences), internally based on the expansion of interpersonal relations of the executive team; externally based on inviting residents of the island and schools to get to know Hua-Zhai.

- Local Empowerment

- Interpreter training: cooperated with local high schools for interpretation training. The training was divided into two stages: the first stage was basic data gathering and learning of Hua-Zhai; the second stage comprised humanities, history, and architectural learning. Interpretation could actually be carried out after satisfying the examination threshold.

- Rooting education: cooperated with local elementary schools to offer courses and lessons based on local features and characteristics, for instance, getting involved in native courses through the production of gross shoes, which, due to the application of traditional woodwork, has become the subject of scientific research, transforming the learning of traditional skills into modern educational research materials.

- Creation of illustrated books: invited local elementary schools to jointly create picture books through oral translation of historical records.

- Spread of Information

- Hua-Zhai 111 Repair Engineering Information Exhibition: an exhibition that focused on traditional buildings, and the materials are available for online reading.

- Production of a guide map: cooperated with local designers to create the map, which included a historical introduction, attractions, traffic information, and so on.

- Active and passive digital guides of QRCode and iBeacon: combined with a navigation map to record guided videos or audio guides; combined with digital technology to promote a digital guide of the settlement.

- Standard explanation manual: an explanation manual mainly used for tourism and educational purposes. The contents included the formation of settlements, the introduction of geographical names, a guide to the whole area, the construction, and so on.

- Photography exhibition of Hua-Zhai: to present the beauty of the living environment of Hua-Zhai from a microscopic perspective through the presentation of photography.

- Augmented reality (AR): combined virtual images and live scenes to reproduce the scene of life at that time.

4.1.2. Cause of Action Transformation

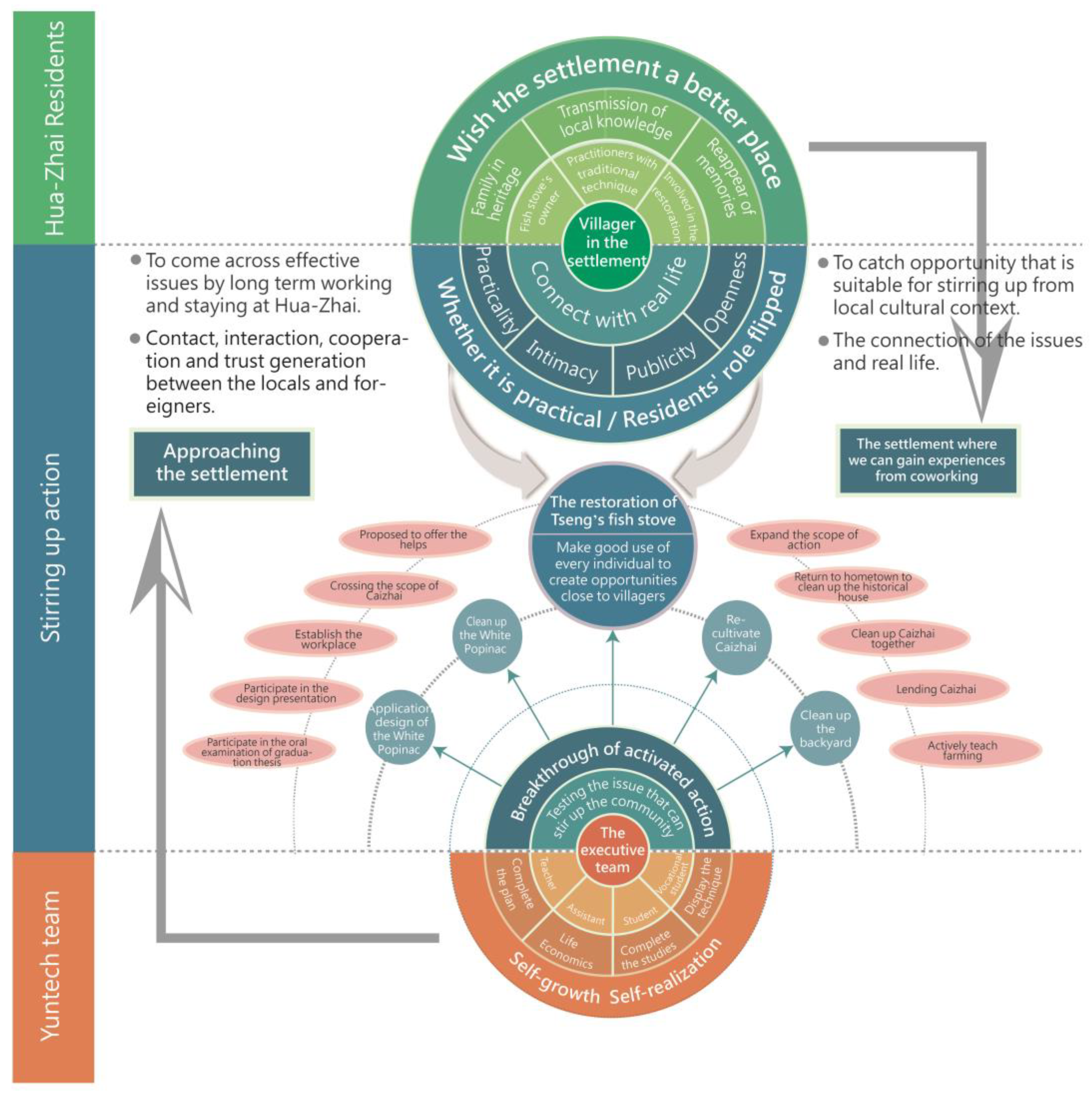

Awareness-Living in the Settlement

Transposition Thinking—Saw It, Heard It, Felt It

Imagine the Future, Depicting Settlement Activation through Experimental Design

4.2. The Test of Activation: Thinking about the Circulation of Community Resources and Creating Values

4.2.1. Backyard Renovation of the Hua-Zhai Service Center

4.2.2. Cleaning Up Caizhai and the Benefits of Diffusion

4.2.3. Cutting Down a White Popinac for Experimental Design

4.3. Breakthroughs of Activation: Restoration of Family Tseng’s Fish Stoves

- Fish Stove. Although it is privately owned, it is an open public space. Besides, it was also regarded as one of the sources of community economy in the era of fish processing. It could engage more people in working jointly, which is important for the cultural landscape in combining the works of nature and of human interactions.

- Caizhai. It is owned by a private individual and has apparent boundaries. Most residents have universal farming knowledge. The arrangement of it is relatively easy, and there is no threshold. The team selected Caizhai as the focus of recultivation because this would enable the team to actively enter the living area of the residents, encourage interaction, and build trust. Because of this, the neighborhood residents were also encouraged to work together and maintain the surroundings actively. Compared to the participation in gathering around fish stoves, the Caizhai was different because it impacted the distribution of regional influence.

4.3.1. Segmentation and Functions of the Restoration Process of Fish Stoves

4.3.2. The First Phase of Restoration: Motivation, Discovery, Evaluation, and Invitation

The Motivations of the Tseng Family

The Motivations of the Tseng Family

- We aimed to persuade our students who had decided to quit the studies into participating in the project proposed by us. Before the executive team had promised to assist, what motivated us was the focus on the way of education and careful consideration given to the future of these outstanding students with sufficient vocational training knowledge. In reality, one of the team members who served as the head of the department had experienced this problem quite often. Most students with outstanding vocational training knowledge tend to interrupt their four years of university studies due to difficult times, and they almost feel overwhelmed by this problem. So, taking this project for example, the head felt concerned about this and said, “This male student quit the studies when I was in charge. So, I wanted to find him back” (field notes). In the meantime, what this idea tells us is that even though his obtaining a university degree is a success, there are still difficulties in the future career development of students such as these who have a major in design. Therefore, we decided to allow these students a chance to bring their talents and skills into full play so as to further equip and cultivate their ability to be in charge of projects independently after graduation.

- The settlement needs to develop its own repair team. In the past, it would lead to subsequent collapse if the historic settlement houses were not immediately repaired. In the face of the gradual restoration of the historical house, it would be difficult to maintain the status quo if an on-site repair team could not be established. However, it was not easy to find a proper person in the local community because the repair task is most associated with the concept of “workhorse”, which refers to a group of people who are lower in social class. Therefore, we attempted to involve students with training knowledge (basic brickwork skills) in relation to this construction work to participate in this task. This further encouraged the locals to reconnect themselves to their hometown. Also, the students could put what they had learned into practice and, thus, inspire local resident interests in putting joint efforts into restoring the historic house through this on-site practical learning. “It is a good idea to learn in Hua-Zhai, and this kind of talent cultivation is the urgent need for the settlement currently. If they can stay, the historic settlement house will have an exclusive restoration team in the future, and its status will become better” (field notes).

- Settlement activation requires more public facilities. The settlement is currently undergoing hardware restoration and software activation. In terms of hardware, the focus is on the restoration of the historical house, which can be divided into two categories: partial subsidies and full subsidies from the government. The historical house with full support would be preserved by the government on their behalf after ten years of its restoration. On the other hand, partially subsidized homeowners may have the right to use the historical house, but part of the use must improve the activation of the settlement. However, houses are valuable private properties. Traditional social housing is a “home”, which is obviously separated from a public space, and this concept is not easy to change. Accordingly, if the focus of activation continues to be on the restored historical house, it would be difficult to have room for implementation. Therefore, the restoration of public spaces that are culturally valuable to the settlement is even more critical.

Mobilizing the Residents of Hua-Zhai and the Teachers and Students of the Executive Team

- How to look upon the students involved in fish stove repair? Give the students an opportunity to try. At first, we wanted to let the students try it out, giving them an opportunity. We were sure that the decision to allow the students to participate in the repair process was the right one. They would learn the local unique materials and techniques through practice, such as the unique shape of Tseng’s fish stove, which also had a complicated internal structure. In terms of smoke exhaust, it was more difficult than just a single-port implementation. We needed to consider the air convection, the rate of smoke exhaust, and the chimney emissions, and the method adopted could not affect the operation of the opposite exhaust pipe. This was a very rare learning experience for the students. “It did not matter even if it was broken after being repaired. It could be restrengthened when it is used. It also did not matter if the shape of the stove was different since it was in the style of the students” (teacher Tseng Wen-Ming).

- The invisible professional division in the settlement made most use the talents and skills with which they were equipped, creating more participation opportunities. Although the fish stove was recognized as industrial equipment, it was also part of traditional construction that contains much local knowledge, which was hidden from us. To make the most use of traditional techniques and, to a greater extent, the wisdom obtained from the encouragement of settlement elders, the elders needed to conduct operational explanations. In this case, the students could go through every step smoothly. Besides, the division of labor in the settlement was considered, for example, the public well of Chang was broken; intuitively, we felt that we had to find Guang-Xiang’s grandpa to handle it. Polishing wall surfaces and removing water chestnuts should be handled by Ma Gai-Xian. If the farming tools were broken, it would be handled by Guang-Xiang’s grandpa, and Mrs. Chen Li-Xiang would be mentioned in terms of the cultivation of Caizhai. By asking different questions in a settlement, we would receive various and reliable suggestions.

- Teacher Tseng Wen-Ming and his spouse in arrangement, adjustment, and translation capacities. The actors mentioned in the preceding paragraphs were mainly Teacher Tseng Wen-Ming and his spouse. In addition to adjustment and arrangement, they also acted as the communicators to work with the repairers because they had an advisory capacity when it came to the construction work. They did not simply communicate the information encoded in the spoken languages; instead, they interpreted the local dialects or regional language and technical language used by the elders, through language switching and body language, to help the repairer understand the meaning of the language and the way of operation so that the repair work could be carried out smoothly.

4.3.3. The Second Phase of Restoration: Launch of On-Site Implementation

The Role and Mission of Local Professionals: Delivery of Local Knowledge and Workmanship

- The traditional technique needed for repairing stoves came from Mr. Yeh Chen-Ren. Mr. Yeh is also known as “MacGyver”; as his name suggests, he could handle affairs of life and work from the original conception, deliberate according to principles, and research and develop to produce all on his own. According to Mr. Yeh’s descriptions, even the house in which he used to live was built by experimenting and making mistakes after observing other sites. Repairing the fish stove is one of the methods to learn about the knowledge of local cultures and customs. This was done by transforming the construction principles of the buildings of the settlement, and the simultaneous understanding of the local culture, through understanding the knowledge acquired from the restoration of the stove. By referring to the concept of “how to mobilize the community” written by Mr. Yang Hung-Ren, the common workings of the daily life of the peasants is described and, based on their value, are ordered as “experience”, “ability”, “technique”, “knowledge”, and “theory” [19]. Accordingly, the students involved as fish stove repairmen were expected to know not only how to repair (work) but also how to operate (technique). The principle (knowledge) was the most important thing to know because this enabled us to gain knowledge of local cultures and customs. Mr. Yeh said, “The operation process of the fish stove is not simply the experience of using fish stoves or building fish stoves; instead, the reconstruction of such a fish stove is because of the increasing demand in use of the stoves used to be used at home in the early years”. Since he started working in the construction industry, he had built a home stove, and even though it had a different shape from an original fish stove, its function, structure, and principle were all the same. Therefore, with his own experience, techniques, and flexibility, he became a supervisor due to his extensive knowledge of building a fish stove. He was one in the tiny minority of residents in the settlement who could operate the construction of the stove. The operation or technical instructions were mainly based on the suggestions given by Mr. Yeh during the restoration process.

- The traditional technique needed for repairing stoves came from Mrs. Chen Li-Shiang. Mrs. Chen was well-experienced in the construction of fish stoves and home stoves. That is because her father was a building construction labor worker, so she has been considerably influenced by her father since her childhood. She has learned how to build a stove through her own repeated applications, revisions, and corrections of the construction procedures. She also took her father’s suggestions in relation to these aspects. In doing so, she knew her users’ needs while doing this kind of construction, and so she always considered how to help them in this regard, including effective cooking times and how to use the firewood, and how to best do the construction so as to allow the stove users to have a high-performance stove. For Mrs. Chen, the materials and techniques of building a stove were not the most important, rather, how to provide the users with stoves designed in an effective way that enabled their best use was of paramount importance (i.e., a stove that is easy to use, quick to fire, and good to use for cooking). In terms of simple construction, regardless of the type of material, even if the stove is for temporary use only and there is no professional technique, it is truly a stove of good use. “Initially, I did on my own. I built a stove that is easy to burn a fire, to save firewood, and quick to boil. First, we started to build the bottom of the stove, and the progress was slow. That was because we had considered the possibility of future adjustments before we started to do the construction. For example, we adjusted the bottom part of the furnace before the completion of it because this process was vital to the final part of the construction. In this case, we adjusted the bottom part of the furnace and made it rather narrower, compared with the top part, which is rather broader. We wiped it from the top (referred to as the cooktop) thoroughly and put a tripod on to it to check whether there was a circle. If so, then it would be fine” (Mrs. Chen).During the restoration, the role Mrs. Chen played in this task was less important than that played by Mr. Yeh. This was because we did not actively refer to the experience we gained from past fish stove work before the restoration. However, through the on-site situations and environment this time, we indirectly aroused Mrs. Chen’s past experiences tied to this task. Thus, she eventually actively participated in the restoration and acted as supervisor and guided us. Gender is not as frequently discussed when it comes to the division of human labor in the settlements. Women are often limited to certain job categories, and they unwittingly maintain a rather traditional role in the community because of male domination and female subordination. So, they rarely have a say in public, nor do they act as a leader to promote something publicly. With this in mind, their potentials, talents, and skills in relation to this task were neglected to a greater extent.

Local Technique for Stove Restoration: Demonstration of Local Instruments and Techniques

A Student’s Respect and Acceptance of the Way the Experts Repaired the Stove

The action he did at that time was actually a superfluous move to the back road.... Grandpa had his own way, when his approach was in use, and we all had to listen to him before we set about the task. However, we secretly modified it in due course. That was because the situation would have become worse if we had disagreed with what Grandpa told use to do. In this way, we would not reply, Grandpa, you can’t do like this.” Also, this was not a big problem for us to tackle because Grandpa just simply wanted to teach us, and he would not stay for the duration of the whole construction process. In other words, Grandpa was there just to teach us what they had known and learnt.(modern techniques)

4.3.4. The Third Phase of Restoration: Evaluation After Restoration

The Fish Stove Is Repaired and It Is Not Bad (koh-bē-bái)

Application after Restoration: Culture Delivery

4.3.5. Analysis of the Overall Fish Stove Restoration

The Locals

- They played the role of activating local knowledge, and the existing science education and techniques used to reproduce the traditional technique complemented their knowledge in this regard. Each actor possessed mutually acceptable joint tasks in this network. In the stage of repairing the fish stove, regardless of the selection of materials, human collaboration, and technical operation, priority was given to local conditions. Upon its repair, the owner of the fish stove invited the local elders, well-experienced in constructing stoves, to join the restoration and to teach the traditional techniques of constructing the stove and collecting the materials. The team unexpectedly discovered that, in addition to Mr. Yeh Chen-Ren, Mrs. Chen-Li-Shiang was also well-experienced in building and using the fish stove; therefore, she actively participated in the executive team. Simultaneously, someone was also invited to be in charge of the settlement construction plan and to assist in the process of material and equipment scheduling and borrowing. Because the “student” was very curious about cement work, this process changed from observing to participating in repair, providing experience in commercial construction. The elders knew the traditional techniques of repairing the stove. The student’s techniques helped to realize the traditional techniques described orally by the elders and re-presented it to the restoration of the fish stove. The value of traditional knowledge moved and honored the elders and made them quite harmonious and willing to share throughout the process.

- Collective memory and cross-regional participation. Based on this study, there is a region restricted to all the local residents and used as their own living area. This settlement area was mainly divided into the following four areas, including Ding-Liao, Xia-Liao, Shen-Ze-Ho, and Wei-Liao. Because of the limited scope of farming, the mobility of the residents in the settlements had been promoted. The fishery restoration process and the post-repair experience activities has made contributions to the cross-regional activities for the residents. Meanwhile, from a historical perspective, the discussions of the past memories of daily life were also triggered, and so the restoration of the fish stove is worthwhile.

- The problem of concreteness. Among the many actions performed by the team, all that the residents were concerned with was as follows:” is it true?” and “doing nothing”. We needed to listen to the voices of the elderly carefully and clearly explain the process of each action involved in the restoration. The meaning hidden in the back of the elderly’s mind was whether the team treated every part of the settlement and everything with sincerity. When the affirmation was accepted, the elderly would say, “I don’t care what you want to do! Do what you want to do” (field notes). This was a sign of rapid acceptance based on trust and understating.

Foreigners (The Executive Team)

- A breakthrough in the community development. As far as dying settlements are concerned, the restoration work of the local heritage must be taken seriously because a major breakthrough in community development is when residents are constantly thinking and trying to create a “link” through action. Such connection represents the link between people and their reconnection with physical objects. With the alteration of time and space, there have been multiple changes in the relationships among people and between people and physical objects, including the use of existing resources, an understanding of the living surroundings, and the “local knowledge” that is accumulated gradually by constantly adapting ways of living to communities [22]. In addition to making good use of “local knowledge”, we gradually discovered that specific, visual, and life-related actions were more likely to produce dialogue through a series of actions. Each action with similar or close values to the local values is more likely to encourage interaction, which, in turn, creates a sense of trust and understanding. Because the locals adapted to the living environment over many years, both the tangible and intangible cultural assets can become the biggest catalyst for local interactions and so enhances the sense of belonging in the stages of community reconstruction, recovery, and development [23].

- Self-growth and self-realization. When each member of the team gathered in Hua-Zhai, in addition to the task of coordinating the project, the goal of self-realization should also be achieved. A detailed review of the executive team’s projects, most of which were independent from the commissioned project in order to increase the implementation of the project, shows motivation from observations to face real problems the settlement is dealing with, which also includes the challenges of self-growth and realization. Settlement activation was common along with the challenges of self-growth and self-realization. Settlement activation is an ordinary case; yet, how to find out a specific solution was also a challenge for the team. When faced with challenges, each person had a different task. The teacher must decide on the research topic in the implementation process and complete the project while facing the problems that arise. The students will enter the settlement, set about the research topic, and seek guidance from their professor. What the assistant needs to work with most directly is the economic needs of the inhabitants. The vocational students combine bricklaying with traditional techniques so that the bricklaying technique can be displayed in the traditional settlement; thus, traditional technology is preserved by the combination of bricklaying.

When the Locals Are in Contact with Foreigners—Fish Stoves and Other Activities

5. Conclusions

5.1. The Long-Term, On-Site Community Design Approach Helps to Identify Effective Discussion Topics

5.2. Community Design Often Finds Opportunities for Disturbance from the Local Cultural Network and Habits

5.3. Community Design Issues Shall Be Connected to the Values of Real Life and Be Practical, Intimate, Public and Open

5.4. Local Priority Shall Be Given to Community Design so the Value of Local Knowledge Is Treated Equally and the Role of the Traditional Craftsman is Reversed

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.C. The Vicissitude of Livelyhood in Peng-Hus’s Wang-An and Jiang-Jiun-Aw Islands. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.Y. Research and Challenges on the Revitalization Action of Wang-An Hua-Zhai in Important Settlement Buildings; Yi Dian Industrial Co., Ltd.: Taichung, Taiwan, 2019; pp. 12–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wangan Township Household Registration Office Penghu County. Available online: https://ris.penghu.gov.tw/wangan/home.jsp?id=154&act=view&mserno=201110250005&yy=2019&&mm=05 (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- Lin, X.H. Policy of Culture; Yang-Chih Publishing: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2009; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.P. Why Build a Temple? The Materialization of New Community Ideals in the Demilitarized Islands between China and Taiwan. Mater. Relig. 2017, 13, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.H. The Falling Fishery on the South Seas of Peng-Hu; Coral Stone: Penghu, Taiwan, 1998; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.Z. Caizhai and Fish Stove in Penghu; Xiying Scenery: Penghu, Taiwan, 1999; pp. 94–104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Administration, D.o.L. Easy Map System. Available online: https://easymap.land.moi.gov.tw/R02/Index (accessed on 30 June 2019).

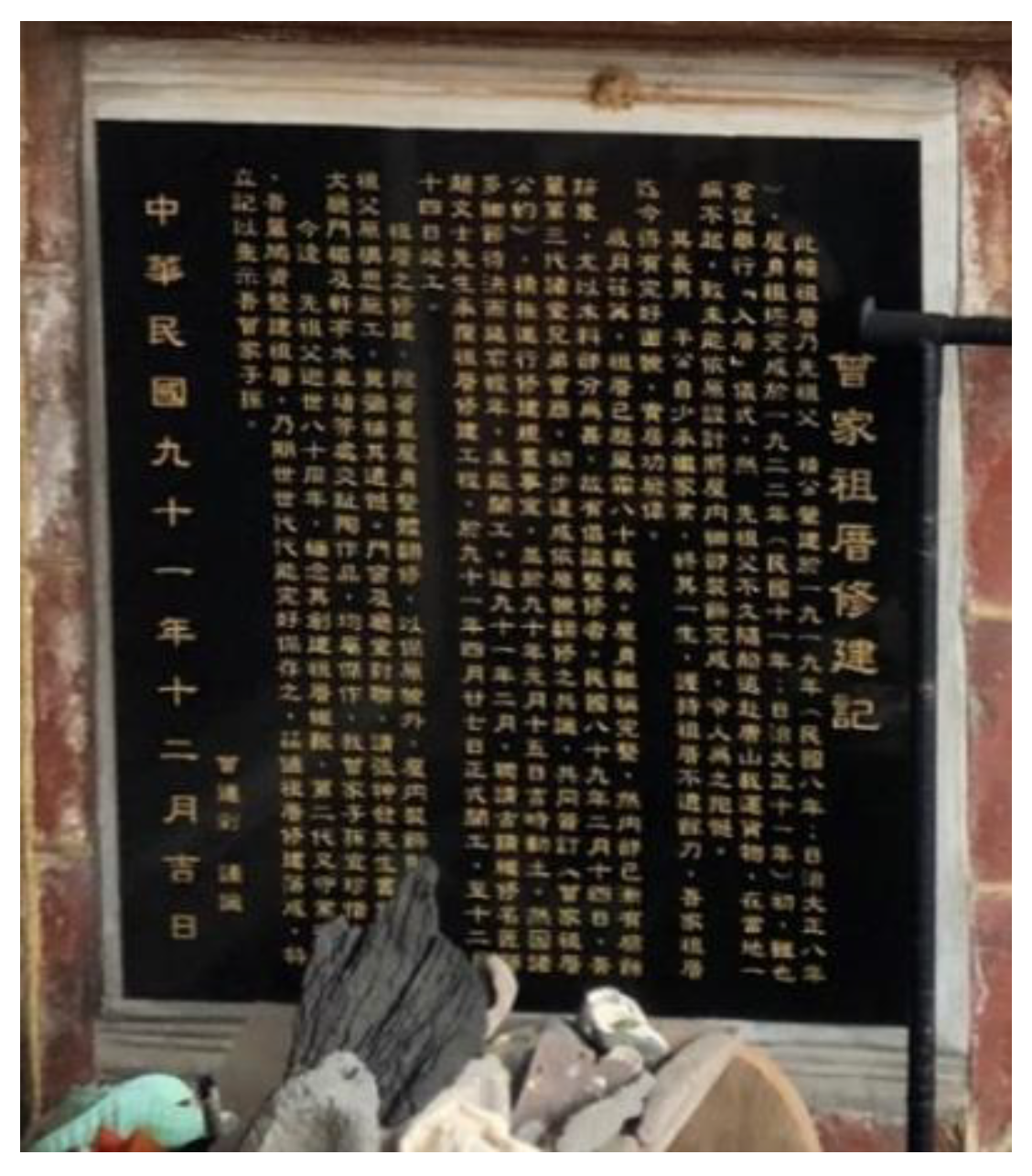

- Tseng, W.M.; Penghu, Taiwan. Wang-An. Hua-Zhai Tseng Family Fish Stove Repair. Unpublished work. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T.; Hsu, T.L.; Wang, C.H., Translators; Place: A Short Introduction; Socio Publishing Co. Ltd.: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2006.

- Tseng, S.C. Community Building in Taiwan; Walkers Cutural Print: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.H.; Miyazaki, K. From Product Design to Community Design—On the Development, Development and Methods of the Overall Construction of the Taiwan Community; Taiwan Handicrafts: Nantou, Taiwan, 1996; pp. 4–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, K.; Huang, S.F., Translators; The Overall Construction of a New Community; Taiwan Handicrafts: Nantou, Taiwan, 1995; pp. 6–22.

- Yamazaki, R.; Zhuang, Y.H., Translators; Community Design; Faces Publishing LTD: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015.

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World and Natural Heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2019).

- Fish Stove in Peng-Hu Area. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/400417913407522/?ref=nf_target&fref=nf (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Chuang, K.C. A Study of the Fish Cooking Kiln in Penghu. Master’s Thesis, Taipei National University of the Arts, Taipei, Taiwan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Wu, L.T., Translators; Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation; Linking Publishing Company: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2010.

- Yang, H.R. Making Community Work: A Case Study of Lin-Bien; Socio Publishing, Ltd.: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Čurović, Ž.; Čurović, M.; Spalević, V.; Janic, M.; Sestras, P.; Popović, S.G. Identification and Evaluation of Landscape as a Precondition for Planning Revitalization and Development of Mediterranean Rural Settlements—Case Study: Mrkovi Village, Bay of Kotor, Montenegro. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.; Davies, S.N.; Lorne, F.T. Trialogue on Built Heritage and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C.; Yang, H.J., Translators; Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, 2nd ed.; Rye Field Publishing Co: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015.

- Fabbricatti, K.; Biancamano, P.F. Circular Economy and Resilience Thinking for Historic Urban Landscape Regeneration: The Case of Torre Annunziata, Naples. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.C. Local Practices of Post-Museums: Treasure Hill. Museol. Q. 2014, 28, 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, E. Guidelines for envisioning real utopias. Soundings 2007, 36. Available online: https://www.net/publication/263378903_Guidelines_for_envisioning_real_utopias (accessed on 30 June 2019). [CrossRef]

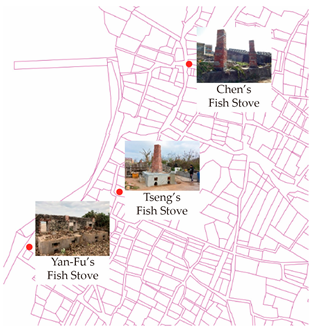

| Name | Style | Surrounding Facility | Current Situation | The Location of Preserved Fish Stoves of Hua-Zhai |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yan-Fu’s Fish Stove | Single Fish Stove | Four single fish stoves, three fish troughs, one stack room. |  |  |

| Tseng’s Fish Stove | Double Fish Stove | One double fish stove, one fish trough, one vegetable farm. |  | |

| Chen’s Fish Stove | Single Fish Stove | Three single fish stoves, several warehouses (for other uses) |  |

| Event | Time to Start | Main Participant | Action Motivation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizer | Secondary Member | Low Participation | |||

| Backyard Cleanup | 11 November 2016 | The Executive Team | None | None | Improve the environment of the service center |

| Tseng’s Caizhai | 8 February 2017 | The Executive Team | Owner of Fish Stove | Minority residents paid attention | Recultivate Caizhai, providing source materials for returning residents |

| The elders and residents of the settlement | Main living ingredients source of the team when living in the settlement | ||||

| A-Kuai’s Caizhai | 1 August 2017 | The Executive Team | Two residents of the settlement | The interaction of residents of the settlement | Agricultural farming experiment base |

| Clean and Design Popinac | 1 August 2017 | The Executive Team | Residents borrowed the restored historic house as experimental space | The interaction of residents of the settlement | Improve the environment of the settlement |

| Promote the experimental design | |||||

| Tseng’s Fish Stove | 4 October 2017 | Owner of Fish Stove | The Executive Team Traditional stove repairer Construction plant manager | The interaction of residents of the settlement The interaction of local elementary schools | Realize the dream of the Tseng family |

| Find ways to stir up community involvement | |||||

| Promotion of local activation of existing settlement hardware facilities | |||||

| The obstacles encountered in the process of training the repairer of community historic houses | |||||

| Learning and future employment considerations for practical vocational experience for outstanding students | |||||

| Event | Resident Participation Degree | Acting Body | Number of Impacted People | Local Knowledge | Collective Memory | Publicity | Concrete Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backyard cleanup | None | The executive team | Not related to life experiences | Obtained a clean garden. | |||

| Tseng’ Caizhai Cleanup | Attended and expressed views in the discussion | The main laborer’s owner of Caizhai due to the physical action produced by the arrangement | The owner of Caizhai, the whole family of No. 114 Hua-Zhai | Intimate, obvious | Contains family memories | Kindness | Drove the whole family of No. 114 Hua-Zhai to organize the surrounding environment of the house Recultivation of 3 Caizhai |

| Recultivation of A-Kui’s Caizhai | Attended and expressed vies in the discussion | The executive team | The owner of Caizhai, The residents of “Dingliaochia” | Intimate, obvious | Contains area memories | Kindness | Obtained interactions with the elders of Ding-Liao. Able to use a Caizhai Got permission to use the surrounding Caizhai |

| Popinac cleanup and application design | Informed, expressed views in the discussion | The executive team | Active diffusion across a range of people | Never appears in life memories | Completed the cleaning of various places in the settlement The elders actively proposed to provide assistance Promote the experimental design study of 2 cases Borrowed space Expanded the interaction with the residents of Shan-Ze-Hou. | ||

| Restoration of Tseng’s fish stove | Attended and expressed views in the discussion Strategy and self-management | Special acting body Main actors: traditional craftsmen, craftsmen, fish stove owners, and planners | Including the owner of the fish stove, traditional craftsman, the residents of the settlement, and local elementary schools | Intimate, practical, high-level of traditional technique | Contains the collective memory of the settlement | Kindness and localized publicity | Repaired a fish stove After the repair, experienced the venue Settlement’s new attractions Rural teaching material for the elementary school Residents actively participated across regions (Chiatou) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.-Y.; Hwang, S.-H. Research on Field Reconstruction and Community Design of Living Settlements—An Example of Repairing a Fish Stove in the Hua-Zhai Settlement on Wang-An Island, Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216066

Wang S-Y, Hwang S-H. Research on Field Reconstruction and Community Design of Living Settlements—An Example of Repairing a Fish Stove in the Hua-Zhai Settlement on Wang-An Island, Taiwan. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):6066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216066

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shu-Yen, and Shyh-Huei Hwang. 2019. "Research on Field Reconstruction and Community Design of Living Settlements—An Example of Repairing a Fish Stove in the Hua-Zhai Settlement on Wang-An Island, Taiwan" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 6066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216066

APA StyleWang, S.-Y., & Hwang, S.-H. (2019). Research on Field Reconstruction and Community Design of Living Settlements—An Example of Repairing a Fish Stove in the Hua-Zhai Settlement on Wang-An Island, Taiwan. Sustainability, 11(21), 6066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216066