Abstract

The city of Turku is located in southwest Finland, in Northern Europe. Founded in 1229, it is the country’s oldest city. It is situated around the Aura River, which flows into the Baltic Sea, making it an ideal location for its 184,000 inhabitants and 20,000 enterprises. In June 2018, the city unveiled an ambitious climate plan to be carbon neutral by 2029. This plan was prepared according to the common model of the European Union (EU) (SECAP, Sustainable energy and climate action plan) with key milestones for years 2021, 2025, and 2029. It focuses on both adaptation and mitigation strategies with six measures outlined as necessary to meet the targets, two of which directly target citizen outreach and engagement. These two measures focus on mobilizing communities as partners in the climate plan and on raising awareness of climate change. Given its significance to the plan, this paper examines stakeholder engagement in the City of Turku’s climate policies from a governance perspective. It asks the question, how does stakeholder participation materialize in the City of Turku’s carbon neutral planning process? It aims to give a snapshot of baseline stakeholder participation in the city’s carbon neutral aspirations. It has found that whilst the plan contains ambitions for stakeholder participation, it is not fully implemented. It recommends a citizen facilitated public participation steering group that aims to inspire citizens towards taking action and engaging in the decision-making process for a carbon neutral 2029.

Keywords:

Turku; carbon neutral; cities; climate change; stakeholder participation; public; engagement 1. Introduction

Globalization has led to a gradually more interconnected world, a trend that will continue into the next century with a ballooning population. The earth’s population is predicted to grow by roughly a quarter from the current 7.7 billion to 9.7 billion by mid-century [1]. This will translate into an additional 13 percent increase in urban areas, rising from 55% in 2018 to 68% in 2050 [2]. This growth means that cities will play an ever more important role in sustainable development. As such, poorly governed urban transitions can lead to environmental degradation, and increased carbon dioxide emissions resulting in temperature rise in excess of the 1.5–2 degrees of the Paris Climate Agreement. The thrust to decarbonise urban societies and for low-carbon solutions to meet the needs of growing populations for the transformative change required for the 1.5 °C trajectory was stressed in the IPCC special report, ‘Global warming of 1.5 °C’ [3]. Urbanization and its accompanying economic and infrastructure development could add an additional 250 GtCO2 by 2050, out of a carbon budget of 800 GtCO2 to keep warming well below two degrees above pre-industrial levels [4]. The science is clear; cities are major emitters of CO2 and as such, it is imperative that they take measures to address climate change.

Cities are motivated to act as they feel the impacts of climate change in the form of extreme weather events due to their location in floodplains, along coasts, or in extremely dry areas. In 2019, such events included flooding in Venice in April, extreme temperatures exceeding 40 °C in Madrid, Montpellier in Europe, and wildfires in Serbia that affected western cities [5]. Expanding cities face stressors such as storm surges, sea level rise, coastal erosion, soil, water salination, and land subsidence [6]. Heat waves in cities are amplified by urban heat islands [3]. Urban areas are also susceptible to higher mortality rates and other impacts on human health due to increased UV and ozone concentration resulting from pollution worsened by climate change [6]. The crisis events have been used by cities as windows of opportunity for transformative shifts. Extreme weather events such as floods or droughts can be labeled as windows of opportunity when harnessed by society to enhance long-term adaptation [7]. They have often led to changes in the rules and decision-making process of cities, leading to new policies and shifts in ways cities and climate change are governed to include the public and broader stakeholders in the decision making process.

The inclusion of stakeholders in the climate change process is not new. It can be traced to the Rio Earth Summit (the 1992 UN conference on Environment and Development) where the agreement of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was inked, with the objective of stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions to prevent dangerous human stimulated effects on the climate system [8]. The inclusiveness of climate governance can be traced to the preamble to the terms of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change [8] that calls for “the widest possible cooperation by all countries and their participation in an effective and appropriate international response, in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities and their social and economic conditions”. This statement refers to the common responsibility of all states, but recognizes the varying degrees that states can enter into a collective response, based on their socioeconomic conditions and their contribution to the problem. One way that states can enter into response to include the public is further stipulated in Article 4 Commitments, 1(i) [8] (p. 6), where all Parties are required to “promote and cooperate in education, training and public awareness related to climate change, and encourage the widest participation in the process, including that of non-governmental organizations”.

The implementation of this commitment is elaborated in Article 6, Education, training, and public awareness, which discusses public access to information, training, and public participation in measures to combat climate change and its effects at the national, regional, and sub-regional levels, the levels closer to cities. As such, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change inked in 1992 represents a process with a wide participation of stakeholders outside the bureaucratic top down decision-making process, as the main actors at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change were environmental groups and businesses in addition to governments. Since then, there has been an eruption in the multiplicity of engaged actors; these include the manufacturing industry, big oil companies such as BP with its renewables section, insurance companies, carbon traders, forestry organizations, and cities, in what has been termed as new actors in climate governance experiments [9]. The recognition of these new actors in the formal lawmaking process of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change can be traced to the Cancun Agreements in 2010, where local and subnational governments were recognized as governmental stakeholders, under a shared vision for long-term cooperative action [10].

This inclusion of actors other than government into the climate regime was further reinforced at the Conference of the Parties (COP20) on December 2014, in Lima, Peru, with the launching of the online Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action (NAZCA) [11]. This Climate Action Portal (as the NAZCA online platform is called) tracks and summarizes individual and joint actions by non-state and sub-state actors. To date, there are 12,468 stakeholders registered on the site, of which 9378 are cities [11]. Momentum was gained from the 2014 action summit in New York, organized by the UN Secretary General, where the Lima-Paris Action Agenda was launched with the goal of bringing stakeholders from civil society together to stimulate climate commitments and implement actions [12]. This initiative of the governments of France, Peru, the UN Secretary General, and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat, intended to highlight the importance and power of collaboration by boosting the operational efficiency of actions to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change. It included the ‘MobiliseYourCity’ program to help 100 cities and 20 developing countries toward implementing sustainable mobility strategies by 2020, with the involved cities committing to reducing carbon emissions from public transportation by 50–75% [12]. More commitments were made in 2015, and this momentum was built up to the COP 21 in Paris.

This momentum was carried forward in the Conference of the Parties (COP21) on December 2015, where 195 countries adopted the Paris agreement. This agreement is the global call to action to prevent disastrous climate change through limiting global warming well below 2 °C and aiming for 1.5 °C [13]. The Paris Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016, when at least 55 Parties to the Convention, accounting for at least 55% of total greenhouse gas emissions, deposited their instruments of ratification, acceptance, approval, or accession [13]. It recognized the role of non-party stakeholders by dedicating section V to them (p. 19), calling on them to address and respond to climate change by scaling up efforts and supporting actions to reduce emissions, building resilience, decreasing vulnerability to the effects of climate change (and to record these actions in the NAZCA) [13]. It called on civil society, the private sector, financial institutions, cities, and other subnational authorities to strengthen knowledge, technologies, practices, and efforts of local communities and indigenous people, and also stressed the importance of incentives for carbon reductions including carbon pricing and other domestic policies [13]. The Paris Agreement also appointed two high level champions (Article 122) to coordinate the annual high-level event and to engage with all stakeholders, including the non-party stakeholders, to further the voluntary actions of the Lima-Paris Action Agenda [13]. Hence, the action of cities and other non-state stakeholders were recognized as important to the achievement of the terms of the Paris Agreement and thus explicitly written into the agreement.

The City of Turku is one of the cities registered on the Global Climate Action (NAZCA) portal, with three logged actions, out of the 30 actions by 12 cities in Finland found on the system [11]. The first action is cooperative, as part of the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate Change and Energy to combat climate change and move to a low carbon, resilient society. The other two are logged as individual actions, for half of the city energy production to come from renewables by 2020, and for a 100% CO2 emissions reduction from 2013 to 2040 [11]. The City of Turku has further launched the ‘Turku Climate Plan 2029’ on 11 June 2018, for a carbon neutral city area by 2029 [14]. The plan focuses on both adaptation and mitigation strategies, and was prepared according to the common model of the European Union (EU) (SECAP, sustainable energy and climate action plan) with key milestones for years 2021, 2025, and 2029. There are six measures outlined as necessary to meet the targets, two of which directly target citizen outreach and engagement. These two measures speak to mobilizing communities as partners in the climate plan and to raise awareness to climate change. Given the importance of stakeholder engagement to the success of Turku’s climate policy, this paper examines stakeholder engagement in the City of Turku climate policies from a governance perspective. It asks the question, how does stakeholder participation materialize in the City of Turku carbon neutral planning process? It aims at giving a snapshot of baseline stakeholder participation in the processes of the City of Turku carbon neutral aspirations. This paper is meant to add perspective on the topic of stakeholder engagement in carbon neutral planning processes, with a methodology limited mainly to document analysis.

2. Participatory Governance

The term governance implies a moving away from state control to include other actors in the decision-making process. This decentralization of policy processes has been advocated in the European White Paper on governance [15]. The inclusion of stakeholders in environmental decision-making was propelled through EU directives such as the Water Framework Directive and its accompanying Public Participation Directive [16]. The common implementation strategy guidance document 8 states that, despite the cost, time, and energy demand, public participation pays off in the end, but is not an end of itself, rather “a tool to achieve the environmental objectives of the EU Water Framework Directive” [17]. Participatory governance has the potential to improve decision-making processes as they incorporate local knowledge and open up the political arena for environmental interests [18]. Participatory governance has been formally defined as ‘‘the processes and structures of public decision making that engage actors from the private sector, civil society and or the public at large, with varying degrees of communication, collaboration and delegation of decision making power to participants” [19].

Engaging the public in environmental decision-making processes is seen as one of the responses to the general lack of effectiveness of environmental policy [19]. The characteristics of climate change as a ‘wicked problem’ with no easy fix solutions, and competing sources of knowledge, values, and interests lends itself easily to public engagement. Climate change is a global problem with local impacts, and its complexity and differing scales makes it a requirement ‘to take account of microscopic as well as macroscopic aspects’ [20] (p. 140), such as the involvement of actors at different scales. It is a problem that encompasses all sectors of society, thus making coordination necessary across policy areas. The uncertainties and incomplete scientific knowledge on the effectiveness of renewables, e.g., make it necessary to incorporate knowledge from all stakeholders, especially indigenous stakeholders, for a more complete understanding and for workable solutions. The uncertainty related to environmental justice, who the victims are, who are the causes of the problem, and where resources should be allocated, makes it necessary to engage actors at all levels, sectors, and ‘walks’ of society for a truly inclusive approach. This will allow the incorporation of different ways of seeing the world and different value judgments by persons who are affected by and affecting the problem, thus enhancing the legitimacy of the decision-making process [19]. Finally, since climate change is irreversible and some damages cannot be repaired, preventative and proactive approaches require diverse knowledge and experiments, and the application of the precautionary principle.

3. Methodology

The latitude of this paper is limited to giving a snapshot of stakeholder participation in the City of Turku carbon neutral planning processes. Stakeholder participation refers to allowing the public to influence plans and decision-making processes [17]. The indicators used in this assessment address the design of the City of Turku carbon neutral plan, and the implementation of the terms within that plan. In this study, the term public means stakeholders who are affected by or can affect the carbon neutral decision-making process through either receiving information, consultation, or active participation [17]. Further, concerning this process, information supply refers to the provision of public access to information on decision-making processes related to carbon neutral planning, whilst consultation implies giving the stakeholders time to react to plans and proposals developed by the municipality. At the other end of the spectrum, active involvement necessitates giving stakeholders a voice in the decision-making process [17].

The literature has not provided a consensus on the benefits of stakeholder participation in environmental decision-making. There are equal examples of participatory processes that led to tangible environmental and social benefits, as there are examples that led to negative outcomes or a failure to meet goals or expectations [21]. Some explanations of the negative outcomes suggest that lower levels of engagement are a form of manipulation and as such advocate for more democratic, co-productive modes [22]. The positive environmental outcomes from participatory processes are not guaranteed, but are dependent on factors spanning three dimensions: breadth of involvement, communication and collaboration, and power delegation to participants [19]. Stakeholders can influence environmental outcomes when there is professional facilitation, which helps to overcome power imbalances, and co-optation of environmental groups, when there is less trustful setting that avoids co-optation and when there are adequate resources [19]. There is consensus in the literature that the quality of the participatory process strongly influences the quality of the decision output [17,19,21,22]. This is the basis of this review, which focuses on the quality of the participatory processes rather than the quality of the decisions made. This methodology was developed with the target audience in mind. In addition to the academic audience, this paper is targeted at city officials, both the City of Turku and other cities who are starting to think about or are in the process of designing carbon neutral plans.

3.1. Evaluating Stakeholder Participation

The word evaluation might connote a subjective judgment about a process or thing. However, as used here, it is the objective and systematic determination of the public participation process in order to pinpoint achievements and highlight gaps that can form the basis of improvement. Assessments can be done via both quantitative and qualitative criteria, but this study is qualitative, as it is exploratory in nature. In this study, the evaluation criteria are important in defining the evaluation framework. This is difficult for, as stated before, there is lack of consensus in the literature as to what represents effective best practices in public participation. This black box of stakeholder participation means that there is no recipe or universally accepted method of evaluating stakeholder participation. However, there are approaches that can be used for specific contexts that focus on key elements of the public participation process [17,21,22].

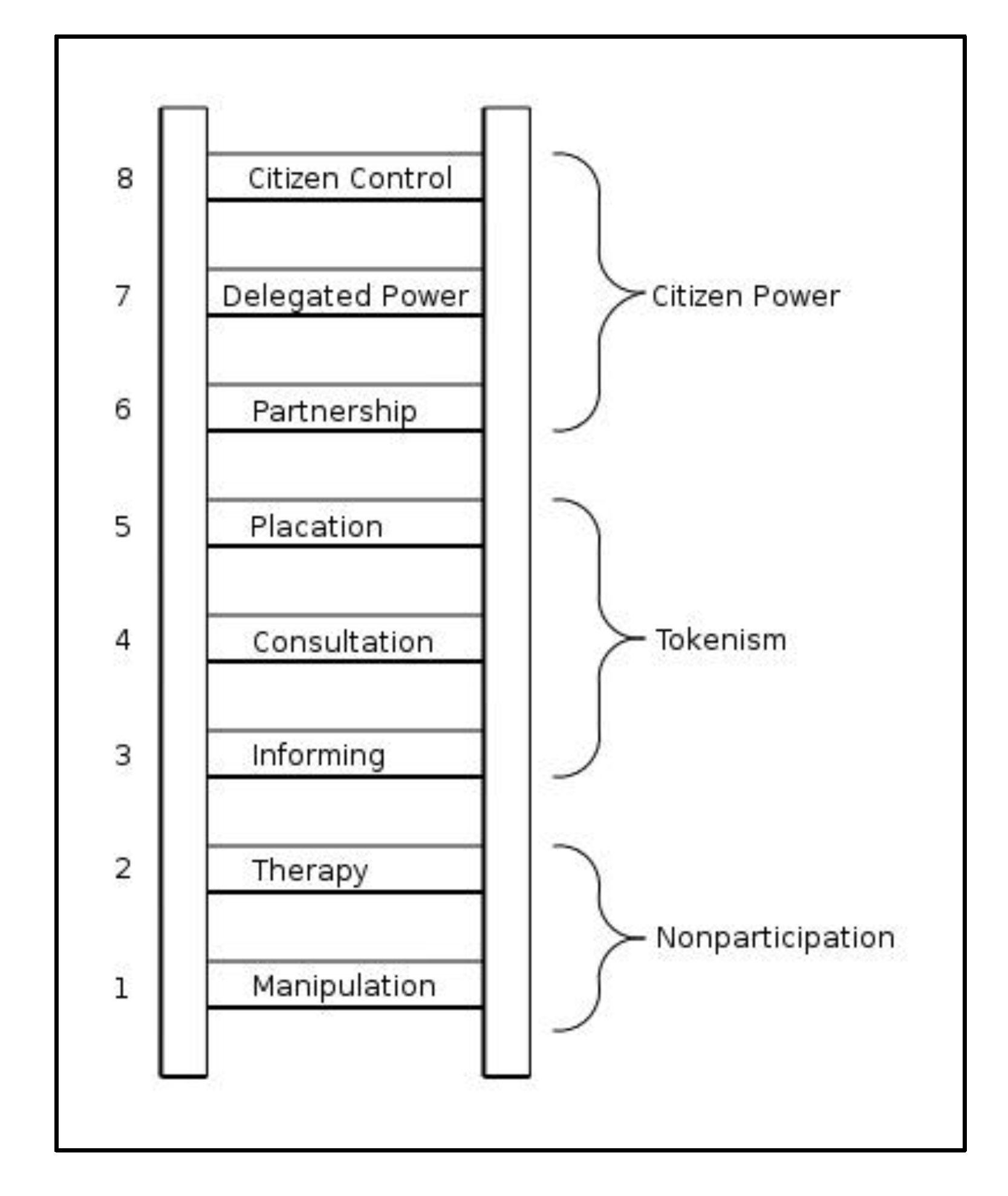

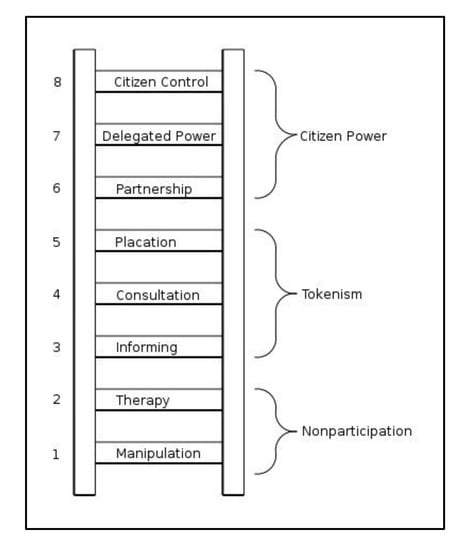

One popular evaluation framework is the Arnstein ladder of public participation, which shows increasing levels of stakeholder participation, starting with nonparticipation on the bottom rung to citizen control on the topmost rung of the ladder [22] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation [22].

Whilst this ladder is useful metaphor for representing stages of citizen participation, it assumes that higher rungs of the ladder are superior to the lower rungs. However, whilst citizen control or delegated power might be useful in some situations, consultation is also useful in other contexts. Reed conducted a grounded theory analysis of the literature on public participation and came up with eight good practices as follows [21]: i. Stakeholder participation needs to be underpinned by a philosophy that emphasizes empowerment, equity, trust, and learning; ii. Where relevant, stakeholder participation should be considered as early as possible and throughout the process; iii. Relevant stakeholders need to be analyzed and represented systematically; iv. Clear objectives for the participatory process need to be agreed among stakeholders at the outset; v. Methods should be selected and tailored to the decision-making context, considering the objectives, type of participants, and appropriate level of engagement; vi. Highly skilled facilitation is essential; vii. Local and scientific knowledge should be integrated; and viii. Participation needs to be institutionalized. Although these factors have gained general agreement in the literature, they focus mostly on the quality of the participation process and not on the perception of the participation process. The literature also identifies nine criteria that evaluate not only the participatory process but also the public’s acceptance of it [23].

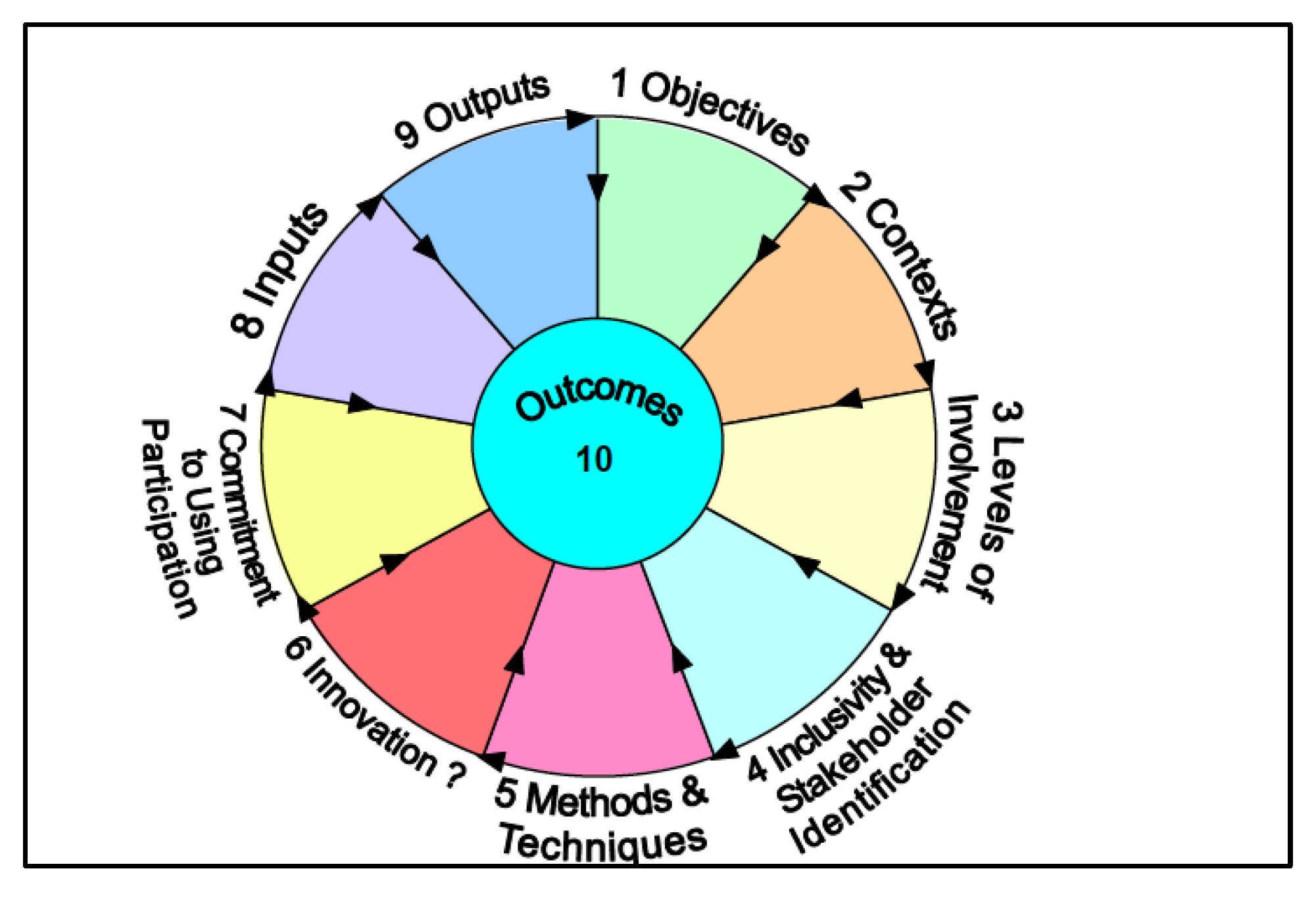

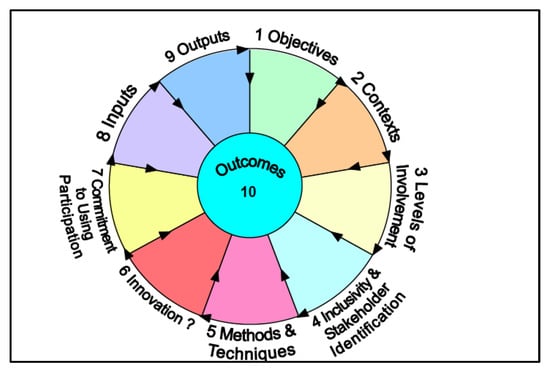

Evaluation criteria can also be found in the social learning literature. Social learning can be seen as an important outcome of successful public participation processes and as such, factors that are important for it are relevant also for assessing public participation [24]. The EU common implementation guidelines for the EU Water Framework Directive offer a ten-point evaluation framework that aims to evaluate both the participation process and the impacts of that process [17] (Figure 2). It starts with the objective of the participation and ends with the outcomes achieved.

Figure 2.

Summary framework for evaluation of participatory processes [17].

This document then goes on to discuss three categories of factors that competent authorities will need to evaluate their own practices and improve the design of public participation in the future: context, content, and process. Context factors refer to existing conditions under which public participation is being developed, and include factors such as the political and cultural environment, environmental conditions, resources, and scale of project [17]. Process factors refer to ways in which stakeholders participate, and include factors such as early involvement, facilitation, and respect [17]. Factors relating to content include valuing diversity of knowledge, evidence and proof, uncertainty, and reporting and communication [17]. This study uses an evaluation framework from the literature that builds on this work. It focuses on procedure (quality of participation process) and perception (perception of the quality of the procedure) criteria for each of the three participation levels; proactive information (PI), consultation (C), and Active Involvement (AI) [25]. This is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evaluation Framework used in study (after [25]).

It gives importance to the perception of the procedure by the stakeholders, as this is essential for engagement and acceptance. In addition, it recognizes that poorly designed procedures that are accepted by the participants can lead to less than optimal decisions [25].

Although these criteria were developed with the EU Water Framework Directive in mind, they are applicable to climate change, as climate and water are inextricably linked. Further, they are applicable to environmental policy making within the EU context. Originating from the common implementation strategy [17], it reflects the work of governmental and nongovernmental stakeholders in EU countries, drawing from diverse points of view. Since the City of Turku based its carbon plan on the EU Sustainable Energy and Climate Plan (SECAP), using an EU endorsed public participation criteria fits well into the objective of this study. The first element listed as a criterion for success in the EU SECAP is to “build support from stakeholders and citizen participation: if they support the SECAP, nothing should stop it” [26].

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This study is based on a content analysis of the City of Turku Climate Neutral Plan 2029 and key documents, such as press releases, relating to the plan. The information contained therein is further elaborated through a key informant interview with a member of the Turk Climate Neutral Plan 2029 writing and design team. For the content analysis, the researcher developed operational definitions of the procedure and perception criteria found in Table 1. The limitation of this paper is that it relies mainly on document analysis and supplemental information from one interview. As such, the main aim of this paper is to add perspective on the topic of stakeholder engagement in carbon neutral planning processes and hence, advance the dialogue on this topic.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results and discussion. Each subsection begins first with a description of the evaluation criterion and then applies it to the City of Turku carbon neutral aspirations.

4.1. Scope of the Process

Climate adaptation and mitigation actions results from processes that define policy goals and tools for their implementation. As such, for key project definition to meet the goals, transparency and participation should be present in each step (legislative initiatives, strategies, plans) leading to the definition of specific projects [25].

In order to address the elaboration of the City of Turku Climate Plan 2029, an introduction to the city is provided to show the context in which the plan was developed.

City of Turku

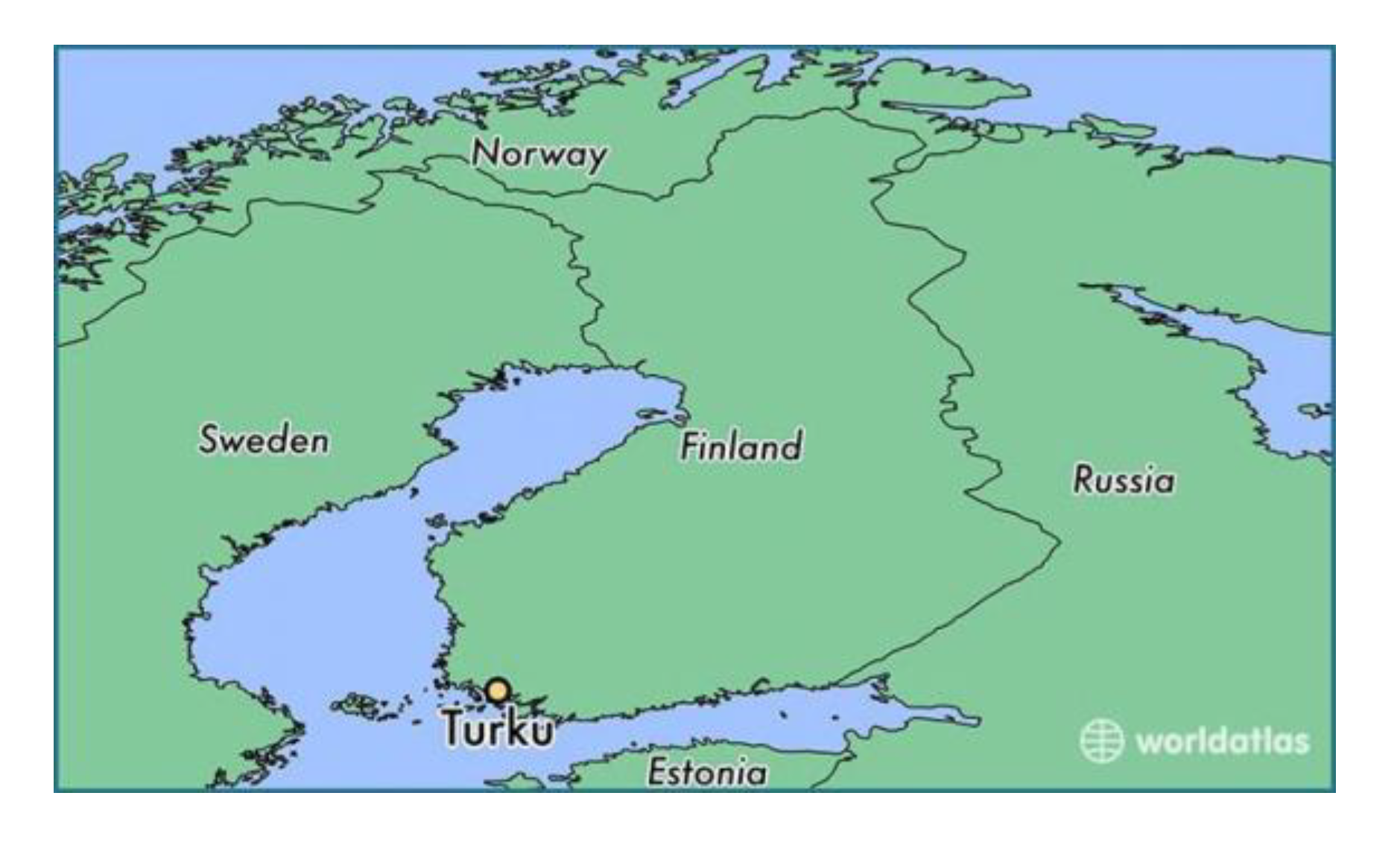

The City of Turku is located in the region of Southwest Finland and is one of its biggest cities (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Map showing Turku taken from World atlas.

The history of the city is said to have started with the letter in which Pope Gregory IX gave his permission to move the bishopric to Turku, when Turku was the biggest city in Finland and one of the most important medieval cities in the whole Swedish kingdom [27]. Turku was important as a stronghold of the Swedish empire, which established the provincial government in Turku in 1617, Finland’s first court of appeal, the Turun hovoikeus, in 1623 and gave the order in 1640 for the first university, the Royal Academy of Finland, to be established in Turku [27]. Russia won the war with Sweden fought in 1808–1809, making the Russian Emperor the ruler of Finland, and Finns Russian citizens. The word Turku originates from tǔrgǔ, an Ancient Russian word meaning ‘market place’ [27]. Turku was made the capital of autonomous Finland, with the central government and Grand Duchy located in the city in 1809. The capital was moved to Helsinki in 1812, as Emperor Alexander felt that Turku was too closely aligned to and geographically too close to Sweden [27]. The City of Turku was founded in 1229 [28].

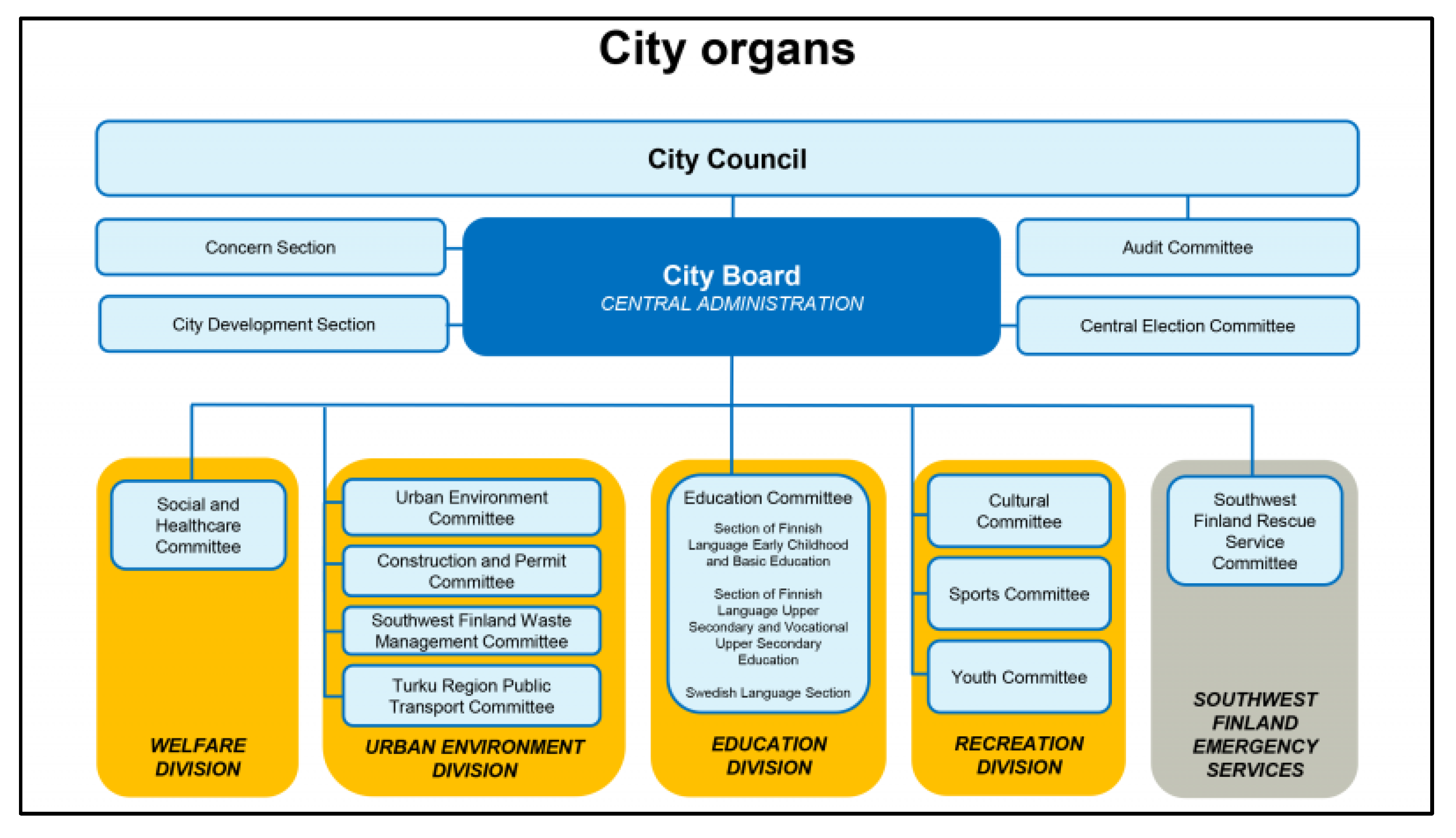

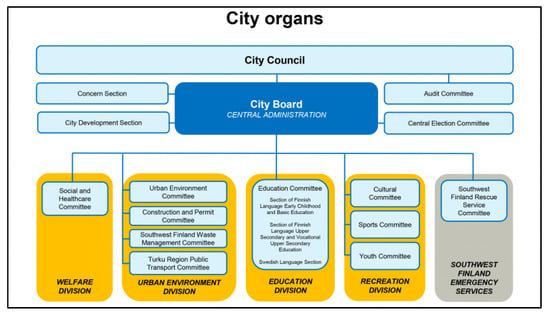

Turku had a population of 12,000 (out of the one million persons in Finland) in the 1820s, which has grown to 184,000 residents in 2019 [28]. These residents elect the city council once every four years in the municipal elections; 67 city councilors and their deputies are elected. As shown in Figure 4, the city council is the highest decision-making body of the city [28] and as such, was the one to mandate and approve the City of Turku Carbon Neutral 2029 plan [29].

Figure 4.

Organizational structure of the City of Turku. Obtained from the city website [28].

The City Development Group at the City of Turku Central Administration holds the responsibility for steering and preparing the climate and environmental policies [29]. All city divisions and Turku City Group’s subsidiaries will implement the climate plan through an assigned coordinating group [14]. The City of Turku Climate neutral plan 2029 originated from a request of the City Board, the Urban Environment Committee, which then prepared the plan in a closed-door room setting in one week [29]. The City Development Section of the Turku City board steers climate and environmental policy [14]. This plan was then sent to the board and subsequently to the city council for approval in June 2018, when the plan was unveiled. Due to the closed-door nature of this meeting to develop the plan and the exclusion of stakeholders in the articulating of the plan and its development, there was a lack of transparency in its formulation. This can potentially limit buy-in and legitimacy of the plan in the eyes of key stakeholders. Stakeholder participation was limited to the interviews for the risk assessment, as will be discussed in the next section.

The caveat is that Turku Energia, the main energy producer in Turku, is owned by the City of Turku. It also holds shares in Turun SeudunEnergiantuotanto Oy (TSE), which sells district heating to Turku. According to Turku Energia’s website, the TSE multiple-fuel power station completed in Naantali at the end of 2017 will have the largest impact on the quantity of renewable energy and emission reductions [30]. A press release on the City of Turku Climate Plan 2029 indicated the support of Turku Energia and TSE for the plan [31]. It quoted Turku’s Energia’s CEO Timo Honkanen as seeing a bright future for energy in Turku [31].

4.2. Selection of Participant

The SECAP identifies stakeholders as those whose interests are affected by the issue, whose activities affect the issue, who possess/control information, resources and expertise for strategy formulation and implementation and whose participation is needed for successful implementation [26] (p. 37).

This section will begin with a description of the City of Turku Climate Plan 2029, with the aim of showing the key sectors and thus stakeholders in the process. It then ends with a discussion on the selection of participant as articulated in the SECAP process.

4.2.1. The City of Turku Climate Plan 2029

Turku, as a participating member city in the Covenant of Mayors, based its carbon neutral aspirations on the EU Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan model [14]. The Covenant of Mayors (CoM) ‘2020 target’ is a 2008 European Commission (EC) initiative launched after the adoption of the 2007 EU Climate and Energy package, in recognition and support of the efforts of local authorities to implement sustainable energy measures for a low carbon future [32]. This initiative will allow for harmonized data compilation and a common methodological and reporting framework that allows for sharing of lessons learnt and best practices to help in reducing greenhouse gas emissions [32]. CoM targets both mitigation (40% emission reduction of baseline by target year 2030) and adaptation actions, and access to secure, sustainable, and affordable energy. The commitment by cities is translated into the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP), which is based on the city’s baseline emission inventory (BEI) and the Risks and vulnerabilities assessment (RVA). Cities commit to reporting and monitoring of their implementation of the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan [32]. Cities are required to commit to stakeholder engagement, and allocating adequate resources for the execution of the plan [32].

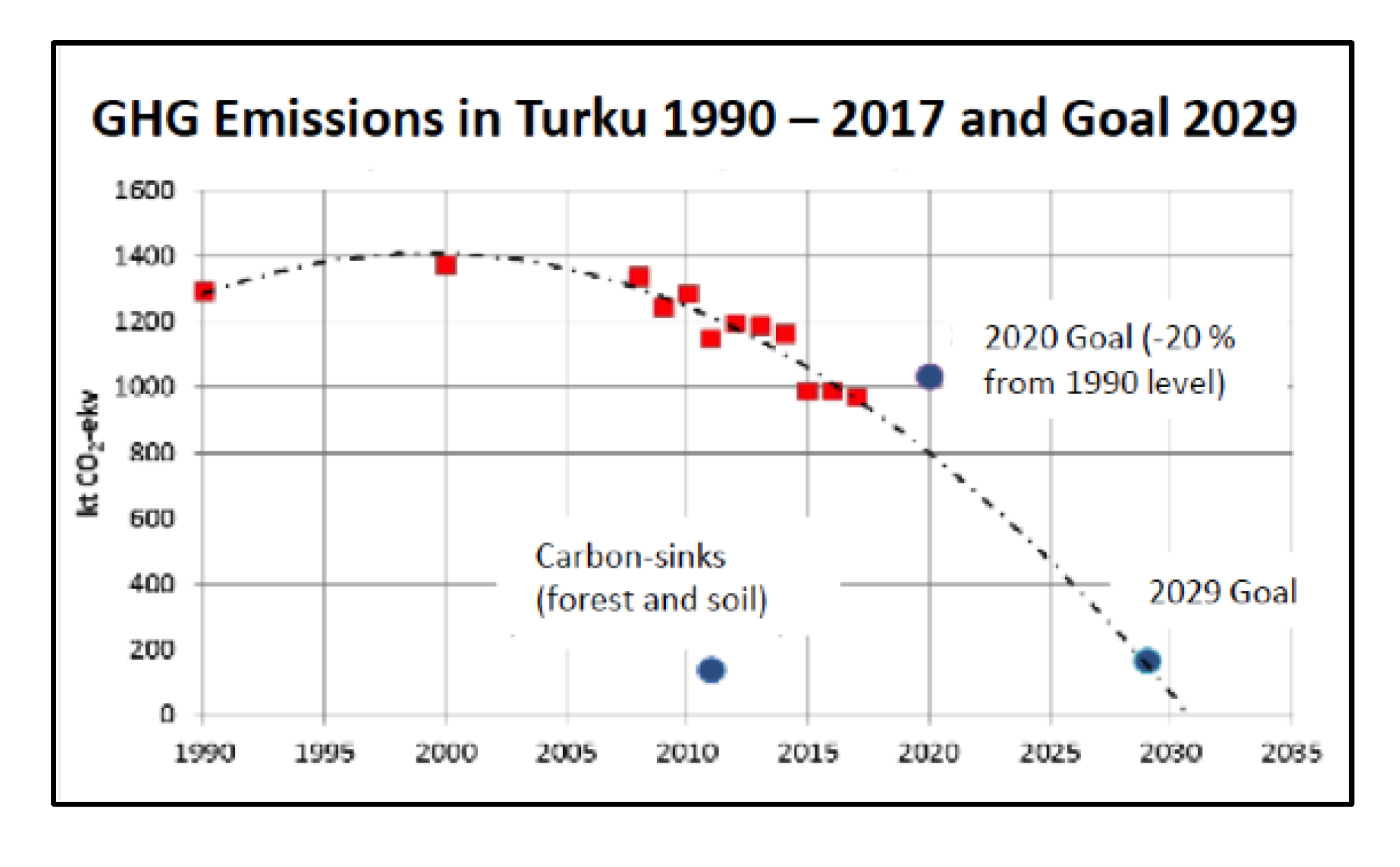

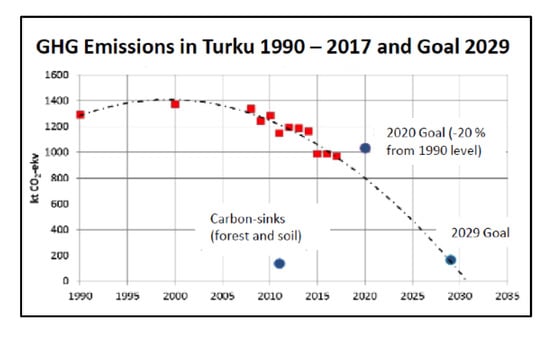

The City of Turku unveiled the City of Turku Climate Plan 2029 in June 2018 with the ambitious target of achieving a carbon neutral city area in 2029 [14] under the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan. It includes climate policies and milestones for the year 2021 (50% emissions reduction compared to 1990 level), 2025, and 2029. Whilst it may seem like an ambitious timeline, the downward trajectory of emissions already achieved by the city makes it a feasible goal [28]. Using the CO2 report calculation method (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions in Turku 1990–2017 and Goal 2029 [14].

In 2005, according to the CO2 report calculation method, normalized greenhouse gas emissions in Turku were 989.0kt CO2 eq, with most contribution from district heating (381.8 kt CO2 eq), electricity consumption (226.8 kt CO2 eq), and road transport (183.6 kt CO2 eq). As Figure 5 shows, this has decreased significantly, with 2015 emissions reduced by a quarter from 1990, with emissions being the lowest in 2017 at 972.2 kt CO2 eq. This was achieved through the increased use of renewable energy in district heat production, particularly from building specific heating (60% decrease of emissions). Industrial and machine emissions (68%) and waste management emissions (42%) have also decreased significantly [14].

4.2.2. Scope of Participants

The scope of participants is directly linked to the scope of activities. According to the city of Turku official [14,29], the main activities are as follows: Sustainable Energy (phase out of coal by 2025 and carbon neutral energy system 2029); sustainable mobility (reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 50% 2015–2029 and carbon neutral transport by 2029); sustainable urban structure (sustainable mobility, energy efficient functional urban areas, vibrant city life and culture); carbon sinks (increasing the capacity to bind carbon and providing ecosystem services) and adaptation and resilience (preparing for climate risks and adapting to change and building resilience). As such, key actors are municipal departments, water and energy utilities, transport companies, shipping companies, local and regional energy agencies, representatives of all levels of administration, financial partners such as OP bank and insurance companies, the ship building sector, public transport Foli, private individuals, universities, union of farmers, agriculture organizations, Union of Baltic Cities representatives, businesses and their organizations, police and fire departments, libraries, port authorities, the army, and the media.

Some of these stakeholders were included in the climate change risk and vulnerability assessment through expert interviews using the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan guidelines. However, the risk and vulnerability assessment was completed primarily using City officials (Development Manager Risto Veivo, Specialist Miika Meretoja, Environement Protection Manager Olli-Pekka Maki, and Environemntal Proteciton Planners Liisa Vainio and Tanja Ruusuvaara-Koskinen) [14], in addition to the wellbeing steering group from the city of Turku. As stated in the City of Turku Climate Plan 2029, stakeholders included one CEO, Electricity use manager, Quality and Environmental Manager, Development Manager from Turku Energia, and a representative from the Union of Baltic Cities sustainable cities commission, and two representatives from the University of Turku [14]. A good commencement, but this small number of stakeholders is not representative of the 184,000 residents and 20,000 enterprises. It is not illustrative of the municipalities, as the Turku Climate Plan affects the energy system of four municipalities, public transport of six municipalities, water management of nine municipalities, land use, housing, and transport cooperation of 12 municipalities, waste water treatment of 14 municipalities, and waste management of 17 municipalities [14]. These municipalities should have had greater representation in the risk and vulnerability assessment exercise and in the overall preparation of the plan.

4.3. Process Design

A good process design includes a clearly laid out participation mandate to manage expectations and to avoid clashes of opinion about the process itself [25]. This includes defining the objective of the participation process, the target audience and a timetable at the beginning of the process [21]. Transparency can be enhanced by effectively managing comments received during consultation through giving of feedback and acknowledging these comments.

The Turku Climate Plan 2029 states that one of the most significant adaptation actions is the increasing of information dissemination on climate. However, there is not much evidence that it is being executed or was applied during the planning stage. In the adaptation scoreboard included in annex 3 of the plan, the item, ‘consultative and participatory mechanisms set up, fostering the multi-stakeholder engagement in the adaptation process’ was given a score of C (25–50% completed), yet there was no evidence of a stakeholder engagement plan [14,28]. This scorecard stated that continuous communication is in place (again 25–50% completed), but apart from a website and news updates on the City website, there is no targeted continuous information. A recommendation would be to use the guidelines (in section 5.2) of the SECAP guidance document to prepare a comprehensive stakeholder engagement strategy. Also, allocate resources to the employment of a public engagement facilitator, as research has shown that this contributes to effective public participation [21].

In the plan, under the section of key measures for meeting climate strategy and vision, the mobilization of citizens, communities, companies, and stakeholders, development partners, and universities—the entire civil society—is listed as key to create climate measures. However, it does not elaborate on its implementation. A detailed stakeholder communication plan and a public participation facilitator are recommended for the success of this objective.

4.4. Capacity Building

This criterion speaks to the provision of adequate human and financial resources through training and financial support so that participants can have access to relevant information and are able to understand and use the provided information [25]. Stakeholders also need to be allocated enough time to provide considered reactions to the documents submitted to consultation [24].

There is information provided about the City of Turku Climate Plan 2029, which is located on the City’s website [31]. However, it is a linked document from a press release, and as such, it is not in an accessible format. This information should be translated into formats for different needs such as visually impaired, children, the elderly, and persons who learn through drawings, rather than words. The plan includes a call to the entire society to create a carbon neutral Turku, and states that common climate work arenas will be created for this purpose, but there no information on how this will be followed through. It also includes a commitment to a yearly climate forum, in which the results of the plan and new initiatives will be communicated, as well as lauding climate champions and accomplished actions and providing communication for all of society [14]. There is no mention of how stakeholders’ comments will be incorporated into the plan or how they can affect the decision-making process. The plan states that ‘sufficient resources are allocated for the task to support the management responsible for climate policy and environmental policies’, but there is no evidence of this. The interview with city official revealed that funding is linked to various city programs and there is no pool of money allocated to the implementation of this plan [28]. Financial support is necessary for effective stakeholder participation, as stated in the literature [21].

Multiple stakeholder engagement fora are necessary for successful mitigation and adaptation planning. According to the SECAP document, stakeholder engagement should be carried out from inception and until the end for it to be a successful process [26]. The guidance document includes guidelines on how to include stakeholders in the elaboration of the plan and in the implementation and follow up. The creation of citizen advisory and steering groups is one example of a successful stakeholder participation strategy. This stakeholder group should be created to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the city environment, problems, public expectations, and guarantee public agreement on indicators for measuring not only the results of the carbon plan, but the participation process, ensuring they have a say in the decision-making process. One of the key examples given is that of Sodenborg, Denmark, which created a public–private partnership for stakeholder engagement called ‘project zero’. It has multiple aims such as branding sectors of society with zero—families, businesses, etc.—but the main aim is inspiring Sodenborg toward carbon neutrality by 2030 [26].

4.5. Level of Empowerment

All participatory processes should engender empowerment and trust, as stakeholders need to perceive that they are heard and have an actual role in influencing the final decision [21,24]. This requires that they are engaged early on in the process so that they can take part in the decision making process from the inception, rather that participating after the decisions have been made. Information should be timely and accessible to participants [21,24].

This is the perception criterion, on how participants perceive the participation process. From the interview and the City of Turku Climate Plan 2029, it was found that there has been limited engagement of stakeholders. Stakeholders were engaged in the risk assessment of Turku, but very few and selected stakeholders who were not representative of the population that will be affected by the plan. The information produced on the City of Turku website on the Carbon neutral plan is not geared at all towards stakeholders. It is not a user-friendly website. As such, it is recommended that the City develops a website for the Carbon neutral plan that is targeted at different audiences and shows real time carbon emissions reduction information. It should also be interactive so that stakeholders can log their individual carbon emissions reduction in much the same way that Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action (NAZCA) portal is organized. Again, stakeholders will have a better chance of influencing the process if they are engaged in developing a communication plan and engaged in a stakeholder steering group for the Turku Climate Plan 2029.

5. Conclusions

The goal of this paper was to present a snapshot of stakeholder participation in the carbon neutral planning processes of the City of Turku, in Southwest Finland. This was done using a framework of stakeholder participation that assesses both the participatory process and the perception of this process by its participants. Since it is exploratory, it is based on document analysis, with elaboration from a key informant interview with a City of Turku official.

This study found that stakeholder engagement, which is a crucial part of the SECAP planning process, was very limited during the development of the City of Turku carbon neutral planning process. The key informant interview revealed that the City of Turku Carbon neutral plan was developed in a week of closed-door team meeting by city staff at the request of council officials. As such, there was inadequate outside stakeholder input into the plan development process, thus potentially limiting the legitimacy of the process. This is also in contradiction with the SECAP stakeholder engagement process, which states that at this stage, stakeholders provide data and share knowledge, participate in the definition of the vision, and participate in the designing of the plan and its elaboration. Since stakeholders were not involved in this process from the beginning, it has the potential to impede implementation through the loss of legitimacy, and through a potentially incorrect plan with incomplete knowledge. A recommendation to bridge this barrier is to consult with stakeholders seeking their inputs on the current plan with the aim to modify the plan by incorporating their views.

This study found that the public participatory processes do not meet the requirements of the EU SECAP process, which, like the EU Water Framework Directive, engages stakeholders at three levels: informing, consulting, and active involvement. There was neither informing, consulting, nor involvement of key public stakeholders in the development of the carbon neutral plan. However, there is some level of all of these processes after the plan was developed. In order to fulfill the requirements of the EU SECAP and the public access to information directive, it is recommended that a public–private stakeholder steering committee be established as partners for steering and implementation of the City of Turku Climate Neutral Plan. Information on this process could be obtained from the city of Sondenborg’s (Denmark) example of public–private partnership ‘ProjectZero’. ProjectZero aims to inspire and drive Sodenborg’s carbon neutral achievement in 2020 through partnerships and cooperation with key actors, and through brand ZERO on all activity sectors (ZEROfamilies, ZERObusiness, ZEROshops). Elements of this example for increasing visibility and buy in should be emulated by the City of Turku.

In the future it is vital to continue informing, consulting and engaging stakeholders through meetings, public forums and as partners in the decision-making process. It will be crucial to monitor the evolution of the participatory process to identify gaps and make necessary improvements. The results of the participatory process and its capacity to effectively engage stakeholders in the decision-making process should be assessed. This evaluation should spill over into public engagement in the drafting and approval of strategies, regulations, and legislation that influence the implementation of projects to achieve the carbon neutral goal in 2029.

Funding

The author would like to acknowledge funding support from the Academy of Finland funded URMI project–Urbanization, Mobilities and Immigration (decision nr: 303619) and the Academy of Finland funded ‘SeaHer’ project-Living with the Baltic Sea in a changing climate: Environmental heritage and the circulation of knowledge (decision nr: 315715). The author acknowledges support from the Åbo Akademi University under the Research profiling area of ‘the Sea’ with the Academy of Finland funding instrument. The author would also like to thank the City of Turku official who gave generously of his time for a key informant interview.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). World Population Prospects, the 2019: Highlights. New York United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs. 2017. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/ (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- DESA, UN. World Urbanization Prospects. 2018. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/ (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Allen, M.R.O.P.; Dube, W.; Solecki, F.; Aragón-Durand, W.; Cramer, S.; Humphreys, M.; Kainuma, J.; Kala, N.; Mahowald, Y.; Mulugetta, R.; et al. Framing and Context. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, H.-O., Pörtner, D., Roberts, J., Skea, P.R., Shukla, A., Pirani, W., Moufouma-Okia, C., Péan, R., Pidcock, S., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Dawson, R.J.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Delgado, G.C.; Barau, A.S.; Dhakal, S.; Schultz, S.; Dodman, D.; Leonardsen, L.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; et al. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature 2018, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Guardian Newspaper. Natural Disasters and Extreme Weather, Europe. 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/natural-disasters+europe-news (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- IPCC. Cliamte Change and Land: an Ipcc Special Report on Climate Change, Destertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/srccl/ (accessed on 17 August 2019).

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Arthington, A.; Bogardi, J.; Bunn, S.E.; Hoff, H.; Lebel, L.; Nikitina, E.; Palmer, M.; Poff, L.N.; Richards, K.; et al. Environmental flows and water governance: Managing sustainable water uses. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1992. Available online: https://UNFCCCc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Hoffman, A.J. Sociology: The growing climate divide. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2011, 1, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. UNFCCC Report of the Conference of the Parties on its Sixteenth Session; UN: Cancun, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- NAZCA. Global Climate Action about NAZCA. Available online: https://climateaction.UNFCCCc.int/views/about.html (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- COP 21. The Lima-Paris Action Agenda. 10000 partners united for climate. Available online: https://www.inbo-news.org/sites/default/files/16029-3-GB_plan-action-lima-paris-A4-def-light.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- UN. UN Treaties Collection. Paris Agreement. Paris 12 November 2015. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-d&chapter=27&clang=_en (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Turku City Council. Turku Climate Plan. 2029. Available online: https://www.turku.fi/sites/default/files/atoms/files//turku_climate_plan_2029.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- EU. European Governance, a White Paper. Commission of the European Communities. Brussels. 2001. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/european-governance-white-paper_en (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- EC. Environment. The European Commission Environment Webpage. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/water-framework/index_en.html (accessed on 17 August 2019).

- EC. Common Implementation Strategy for the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC), Guidance Document 8. Public Participation in Relation to the Water Framework Directive Produced by Working Group 2.9–Public Participation. 2003. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/0cbbda1e-ac34-44ea-93f5-5a51920ba063 (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Pellizzoni, L. Uncertainty and participatory democracy. Environ. Values 2003, 12, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochskämper, E.; Challies, E.; Newig, J.; Jager, N.W. Participation for effective environmental governance? Evidence from water framework directive implementation in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mormont, M. Towards concerted river management in Belgium. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1996, 39, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. A typology of public engagement mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2005, 30, 251–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippett, J.; Handley, J.F.; Ravetz, J. Meeting the Challenges of Sustainable Development-A Conceptual Appraisal of a New Methodology for Participatory Ecological Planning; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1–98. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, L. Facing the water framework directive challenges: A baseline of stakeholder participation in the European Union. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoldi, P. (Ed.) Guidebook How to Develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP)–Part 1-The SECAP Process, Step-by-Step Towards Low Carbon and Climate Resilient Cities by 2030; EUR 29412 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-96847-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turku. Information about Turku. Obtained from the InfoFinland Website. Available online: https://www.infofinland.fi/en/turku/information-about-turku (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- City of Turku. Turku Facts. City of Turku Website. Available online: https://www.turku.fi/en/study-turku/welcome-turku/turku-facts (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Interview with City of Turku Official. Three hours in depth interview with City of Turku Environmental official. 2019.

- Turku Energia. Energy Supply. Available online: http://vsk2017.turkuenergia.fi/en/energy-supply/ (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Turku News. Turku’s New Climate Plan to the Global Forefront. Available online: https://www.turku.fi/en/news/2018-06-08_turkus-new-climate-plan-global-forefront (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- EC. Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy Europe. Guidebook How to Develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).