Abstract

Public sector innovation labs have gained increasing importance as one of the material expressions of public sector innovation and collaborative governance to address complex societal problems. In the current international context, there are various experiences, interpretations, and applications of this concept with similarities and differences but all of them are based fundamentally on the establishment of new forms of participation and collaboration between governments and civil society. This paper aims to examine, through a case study, how policy innovation labs could play a prominent role in promoting decision-making at the local level in order to create a more sustainable public sector. To do this, this article focuses on an analysis of the “Gipuzkoa Lab”, a public innovation lab developed in the Gipuzkoa region located in the Basque Country, Spain, in order to confront future socio-economic challenges via an open participatory approach. An analysis of a pilot project to address worker participation, developed within this participatory process, indicates that these collaborative spaces have important implications for the formulation of public policies and can change public actions, yielding benefits and engaging citizens, workers, private companies and academics. This paper provides a contemporary approach to understanding good practice in collaborative governance and a novel process for facilitating the balance between the state and civil society, and between public functions and the private sphere, for decision-making. In particular, this case study may be of interest to international practitioners and researchers to introduce the increasingly popular concept of public sector innovation labs into debates of citizen participation and decision-making.

1. Introduction

Public sector innovation and collaborative governance have become key in the creation of public and social value, by facilitating the internal and external management, design and legitimation of public policies, favouring social diversity and strengthening the role of citizens and civil society through direct democracy channels [1,2,3,4,5]. Moreover, governance networks have paved the way toward a better understanding of how creativity, experimentation and innovation can contribute to the improvement and greater impact of the decision-making process [6,7,8].

In this context, public sector innovation labs have become a vehicle for alternative policymaking, by turning collaborative trans-disciplinary spaces of socio-political experimentation into a revolutionary process that is changing the way in which we address and understand traditional policies and decision-making processes. These labs involve a diverse and combined series of key actors/agents, from policymakers and civil servants to practitioners, academics, non-profit organisations and social innovators, to co-create, co-design and co-participate in the design of public policies, with the purpose of improving social welfare standards and institutionalizing a new way of doing things [6,9,10,11].

In light of these changes, the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa in the Basque Country developed the Gipuzkoa Lab in 2016 as part of their Strategic Plan (2015–2019) to build and institutionalise a new model of open and collaborative governance in Gipuzkoa. The Gipuzkoa Lab is defined as a public sector innovation lab for social and political experimentation to co-design and test solutions to different socioeconomic problems. This policy innovation lab is also part of the public program ‘Etorkizuna Eraikiz’ (translated into “building the future” from the Basque language), which is focused on the development of a shared governance and strategic reflection framework with different stakeholders—civil society, regional private companies, practitioners, social entrepreneurs, civil servants and universities—in order to collectively decide on the future socioeconomic and political challenges of the region. This program is recognized by the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, led by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [12], as one of the best practices in collaborative and participatory governance which, therefore, represents a case of international relevance.

In this context, this article aims to examine how policy innovation labs can play a prominent role in promoting decision-making at the local level in order to create a more-sustainable public sector. Through the analysis of one of the laboratory’s main projects, Gipuzkoa Lab Participation, the paper demonstrates new ways of creating public value, institutionalizing an open and collaborative governance model that offers new communication channels for citizens, workers, private companies and academia. This pilot project is focused on the improvement of workplace participation policies in the province involving different companies, workers and the provincial government through a shared and collective learning strategy across sectors.

In order to analyse this lab, this paper is structured as follows. The first part of this article will discuss the theoretical foundation of the concept of public sector innovation labs and analyse the influence of collaborative governance and public innovation models in policy design. The second section will address the context surrounding the Gipuzkoa Lab and the methodological approach behind the mentioned pilot project that involves workers, private companies and the public sector as key actors in society. Finally, we will present several of the results and learning experiences behind this initiative and its future research implications.

2. The Scope of Public Sector Innovation Labs

Policy innovation labs are new emergent structures in public service redesign [13]. Their emergence can be seen as one of the elements in the current public sector innovation discourse and related reform attempts [11]. However, these structures have received little attention in the framework of policy science or public management literature. According to Price (2014), these labs have existed in some form for a century but the labification of the policy field has rapidly accelerated since 2010 [13].

The emergence of policy innovation labs has been associated with various trends [14], including growing interest in evidence-based policymaking [15] and the search for open government practices [16] to foster trust and transparency [17] (p.192). Contextual factors, such as the economic crisis, have pressured public sector institutions to search for more efficient public-service delivery models and practices [11].

The main aim of policy innovation labs is applying the principles of scientific labs through experimentation, testing process, monitoring and measuring. In the public sector, innovation labs seek to provide approaches, skills, models and tools beyond what most trained civil servants usually possess [18]. This necessitates the creation of spaces and opportunities for collaboration [4]. According to Tõnurist, Kattel and Lember [11], there are six reasons the public sector could create these laboratories—external complexity (context), technology, competition between old and new structures, emulation, consolidation of experience and learning. At the same time, Demircioglu and Audretschb [19] suggest that internal factors, such as experimentation and motivation to make improvements in the public sector, are strongly associated with the need to innovate in the context of the public sector and, therefore, generate platforms that facilitate the development of these processes.

In this framework, policy innovation labs seek to promote and improve collaboration [18]. In other words, policy innovation labs are defined as trans-disciplinary collaborative spaces where professionals from different sectors coexist to create a mature democratic sphere, working together with the government and other key stakeholders. According to Marlieke Kieboom [20], these laboratories are spaces for social and political experimentation, composed of teams that support public and social innovation from a systemic point of view and, therefore, should not operate alone but be part of larger structures. That is, they are not designed to obtain short-term results nor to seek the re-election of their political and institutional representatives but to improve the well-being of citizens in the long term, which translates into the new institutionalisation of innovative policies and practices. Policy innovation labs are a response to the cross-cutting nature of contemporary policy and social challenges [14].

On the other hand, it is important to highlight that in both the private and public sectors, innovation laboratories can be heterogeneous in terms of their activities, scales and organizational structures, and this condition can be difficult for analysing practical experience [11].

3. The Influence of Collaborative Governance in Public Sector Innovation Labs

The crisis of representative democracies and the nation-state are changing the nature of public administrations and contemporary politics. The growing disconnection and disaffection of citizens towards politics and political parties, accelerated technological change and the socio-economic transformations suffered globally by the new power granted to markets [21,22] have contributed to the progressive distancing between the economy and politics, causing political agency to lose power and creating a gap even more distant from the needs and interests of voters [23].

In this context of rapid socioeconomic and political change, one of the virtues of governance models has been their ability to fill and shorten the gap between political institutions and citizenship. In fact, governance is largely a mechanism that favours public intervention in deliberation and political decision-making, by creating an intermediate political space, a new connector between political leaders and citizens that amplifies the diversity of the actors and networks involved [1,2,24,25,26]. This approach has often been related to public–private cooperation, which is defined as a mechanism that governments develop in order to join forces with private organizations and social agents [27]. Cooperation can take a variety of forms, such as agreements to develop projects and public policies, sharing of investments, providing public infrastructure, among others. In this framework, the pursuit of public policy reform and the re-institutionalisation of the mechanisms by which we address these participatory processes are bringing these perspectives closer to direct democracy initiatives.

It is precisely in this intermediate political space that collaborative governance has managed to bring together a diversity of public and private social actors with the aim of promoting cooperation and the exchange of knowledge in order to guide social problem solving [5,28,29,30]. Public innovation [4,31] and social innovation [7,32,33] have also played a key role in these processes through the creation of new public and social values [34,35,36], combining top-down and bottom-up approaches to socioeconomic and political problem solving.

Therefore, this mobilization of social actors, resources and knowledge not only pursues the exchange of ideas but also the achievement of better solutions through shared learning motivation structures. These formal and informal structures have also been approached in depth from network and interactive governance perspectives [3,37,38,39,40].

Ansell and Gash [29] define collaborative governance as a “governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collaborative decision-making process that is formal consensus-oriented and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public program assets” [29] (p. 544). Emerson, Nabatachi and Balogh [5] define collaborative governance as “the process and structures of public policy decision-making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government and/or actor the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished” [5] (p.2). If collaborative and network governance are the umbrella under which these new deliberation spaces are housed, policy innovation labs are a practical or material expression used to achieve public innovation.

In the book edited by Ezio Manzini and Edward Staszowski entitled “Public and Collaborative: Exploring the intersection of design, social innovation and public policy” [8], these authors reflect on the relevance and possibilities offered by collaboration as a way to improve public services. This collaboration can be based on two complementary approaches—first, a perspective centred on people where there should be greater involvement of the user in the research, prototyping, experimentation and implementation of public services; second, the direct involvement of citizens as the main drivers of the transformation process—that is, public bodies must participate in the co-production process where the users are empowered to co-design and co-implement their own service programs supported by public officials [8]. Perhaps the most important value attributed to the different forms of collaborative governance is the importance assigned to participatory processes—that is, to the capacity to generate opportunity structures for participation, regardless of the benefits and results obtained.

In this vein another, important feature of these labs is their focus on design. Already in 1969, the economist Herbert A. Simon [41], the main precursor of this conceptual paradigm, defined design as “the human effort to convert current situations into preferred situations” or as “the expression of a desire and its materialization” [41] (p.4). Designers must be able to integrate specific knowledge, thereby combining theory with practice—that is, drawing a path between the definition of a problem and its solution. Regarding this issue, Christian Bason [6] argues that the perspectives supported by design help public managers to explore in detail how the relationship between the public system and its users operates, offering these managers the possibility of closely observing the results achieved by their organizations via the concrete capture of the citizen’s actions and discourses immersed in this process. The experiences of the users are directly connected with the scope of the concrete results and the creation of user-driven innovations [42]. The methodologies based on this design are more open and interactive, allowing the direct visualization and prototyping of solutions, their testing and their final implementation. This is a relationship of mutual enrichment with citizens, where new public and social values are generated inside and outside the system [6], integrating a participatory mindset by considering not only an expert mindset. In a participatory mindset, users are partners and active co-creators; in an expert mindset, users are subjects and reactive informers [43,44].

Within this framework, the case study analysed based on the pilot project “Gipuzkoa Lab participation” represents an experimental attempt to achieve these kinds of results in collaboration with different companies, by trying to co-design and co-implement a new political agenda to improve worker participation in the territory.

It is important to highlight that the main focus group in this participation process would be the workers themselves as citizens/key users of the workplace within companies that have a key influence on society as creators of jobs, wealth and development. Their actions exceed the economic dimension and transcend other areas, including the social dimension. The positive effect that companies should have in terms of contributing to their stakeholders and to society in general is highly significant. Companies’ decision-making processes have impacts on communities, workers and the environment. For this reason, according to Vicky Smith [45], worker participation is crucial for the redefinition of private and public organisations in the 21st century, in order to achieve institutional change and create adequate policies to reform the organisation of work and labour [45]. The engagement of employees through direct and indirect channels of participation in the workplace is key for the identification and development of internal and external solutions.

The participation of workers, among other incentives, such as internationalization, innovation, digitalisation, and so forth, facilitates the development and survival of competitive projects that can generate wealth and employment for any country or region across the world. This process can also contribute to the improvement of the region’s entrepreneurial culture and social cohesion. Open participation favours a greater rootedness of the companies’ decision centres at the regional level and reinforces local value chains, thereby contributing to the generation and maintenance of the jobs and the wellbeing of citizens. The participation of people in the ownership and results of the company can also create a more cohesive and responsible territory, with smaller dispersions of income and with more compromised workers, favouring the attraction of talent.

In this context, Oeij and Dhont [46] stress that open communication and participatory structures inside companies can facilitate the learning process of workers and employers inside the organisation but systemic change is only achievable if there is an institutionalized negotiation between the involved stakeholders, workers, employers, unions, policymakers and so forth, covered by a structured legal policy framework that is capable of generating trust among them [46]. The next sections attempt to address how the Gipuzkoa Lab Participation project responds to these issues.

4. Methodology

This paper is based on a case study analysis. This research was conducted through qualitative methods, considering three data sources. First of all, official Gipuzkoa government documents were analysed, including strategic plans, studies and project reports published by the Corporate Governance Department (see Table 1).

Table 1.

List of documents analysed.

These documents contain detailed and useful information about the design and methodology of the public policy laboratory Gipuzkoa Lab. Secondly, data were collected from the outcomes reported by laboratory projects that involved different stakeholders, such as consulting firms, universities, research centres and companies with a special emphasis on actors focused on workplace participation. More concretely, projects occurring during the two periods, 2016–2017 and 2017–2018. On the other hand, in November 2017, the Gipuzkoa government organized a workshop to share the objectives, strategies and priority lines of action to boost worker participation in the region. More than a dozen organizations attended the workshop and the minutes and conclusions were consulted and analysed to identify topics highlighted by participants, thereby elaborating descriptive summaries and further evaluating the connections of these issues with the conceptual framework and the objectives of the case analysis.

Finally, four exploratory interviews were conducted with the officials responsible for the Gipuzkoa Lab and workplace participation program (see Table 2). Interviews were recorded and transcribed. The purpose of the interviews was to gain insight into the structural characteristics of the public policy laboratory and clearly define the roles played by the different actors involved in the Lab.

Table 2.

List of interviews.

Consequently, the interviews generated the testimonies and opinions of key informants in relation to the origins, development and future prospects of the Gipuzkoa Lab and its pilot project Gipuzkoa Lab Participation. The information collected during the interviews provided a better understanding of the general context in which the Etorkizuna Eraikiz program and the public innovation lab Gipuzkoa Lab are framed. At the same time, the interviews helped establish a vision in relation to the main barriers and drivers in the implementation process of the pilot project Gipuzkoa Lab participation, as reflected in the results section.

5. Public Sector Innovation Lab: Gipuzkoa Lab

5.1. Introduction to the Regional Context

The Basque Autonomous Community (2,173,210 inhabitants) is located in northern Spain and is divided into the Historical Territories of Bizkaia (1,141,442 inhabitants), Alava (321,777 inhabitants) and Gipuzkoa (709,991 inhabitants). The region of Gipuzkoa, which this analysis focuses on, is a province that borders the Southeast Basque–French region and has 11 districts and 88 municipalities.

Each of the mentioned Historical Territories has its own provincial government organized around their Provincial Councils and Regional Laws, with broad powers for the administration and socio-economic and political management of each region. These powers are framed in the Basque Country’s capacity to establish its own self-governing bodies, which are uniquely granted through the Statute of Basque Autonomy, which was passed on the 18th of December of 1979, right after the Franco regime and recognised in the Spanish Constitution. This means that Basque Country and Navarra are the only Autonomous Communities in Spain that have right over their own tax regulations, healthcare, public safety and education, as well as complete control over their own internal territorial organization. As a result, the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa possesses recognised competencies as a provincial institution, especially in the areas of finance, economic development, roads and social policies.

5.2. Gipuzkoa Lab

The Gipuzkoa Lab is framed inside the Participation Strategy for the period 2016–2019 [47] and the public policy program Etorkizuna Eraikiz (building the future in Basque language), developed by the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa. This program is the result of a strategic reflection and planning process carried out by the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa between 2015 and 2019 to redirect public policies and promote the innovation of the Gipuzkoan Institutional Governance System, thereby strengthening it, making it more dynamic and adapting it to demographic, economic, social, productive and environmental challenges, while defending the welfare and sustainability of the territory [48].

This strategy also responds to the challenge of the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa to provide solutions in a collaborative way, combining knowledge and experiences that can help to jointly build a shared future for the territory. This discussion process involves different actors/agents, including civil society organisations, the private sector, academia, civil servants and policymakers [48].

The Gipuzkoa Lab represents the materialisation of these actions and, therefore, the core of the participation strategy and Etorkizuna Eraikiz program. According to the report “Experimentation methodology of Gipuzkoa Lab” [49], the public policy laboratory at the Gipuzkoa Lab seeks to promote a prospective exercise to build public policies related to challenges in the medium term. The Gipuzkoa Lab was born with the aim of transforming organizations and companies into “laboratories” to test economic, social and cultural policies. In this sense, the innovation processes that take place in the public policy laboratory happen through pilot projects (developing in Gipuzkoa Lab) applying and sharing experiences with the territory and drawing conclusions about unsuccessful experiments.

In order to select the projects, the laboratory identifies demographic, economic and social challenges that the territory will face in the medium term [49]. This selection is done through the definition of a series of topics that are divided into strategic, experimental and public interest topics in the following areas [49]:

- New models of public governance

- Equality and Diversity

- Audio-visual communication of the Basque language

- Reconciling work and family life

- Workplace participation

- Active aging and socio-sanitary systems

- Environmental sustainability

- Community and territorial development

- Social transformation and entrepreneurial impact

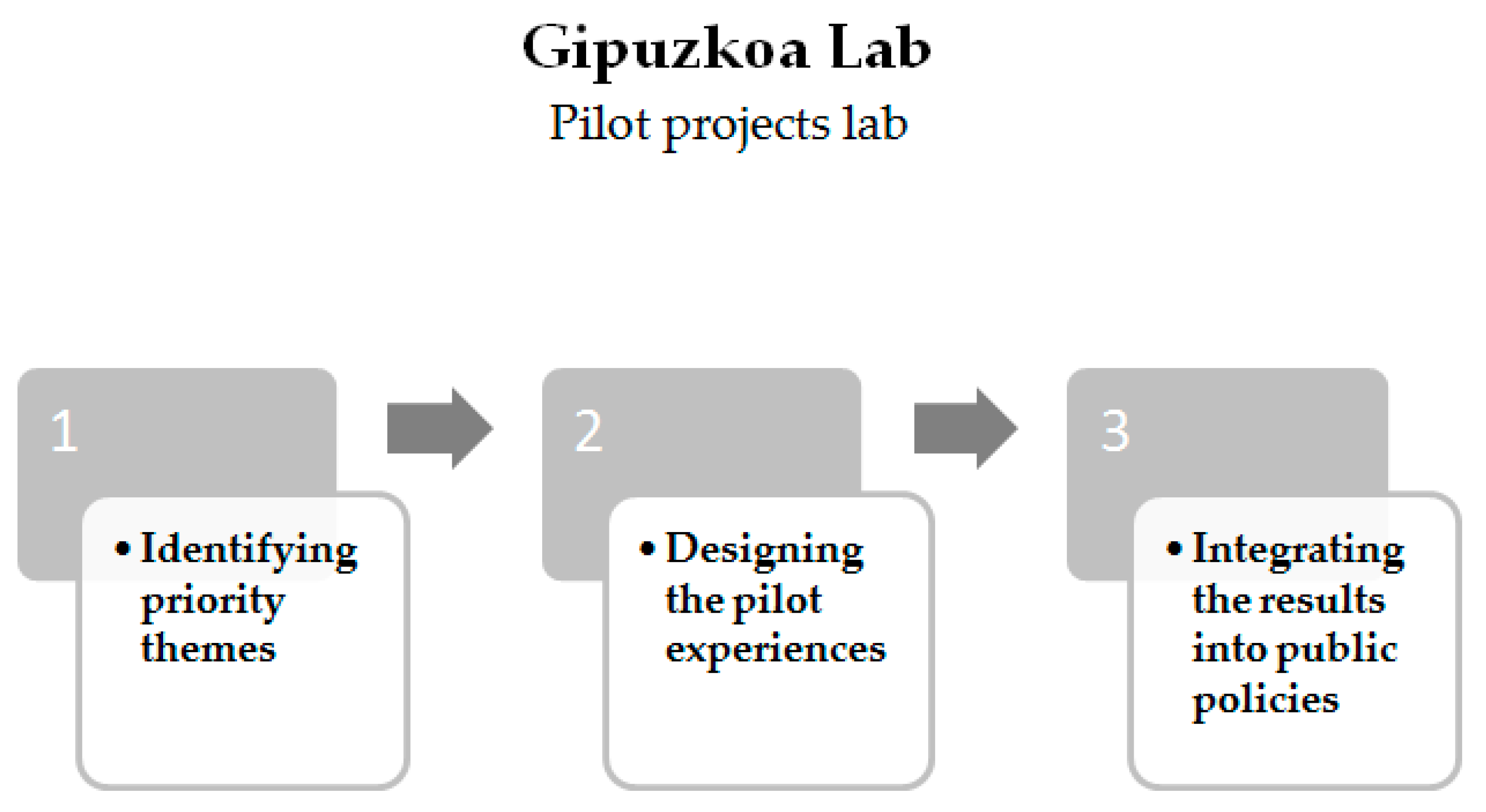

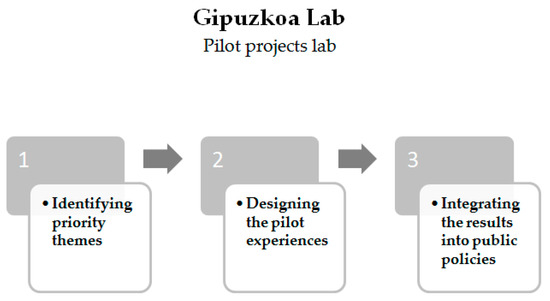

The dynamic of the Gipuzkoa Lab is to implement projects via three modalities: a) those that are implemented directly by the Provincial Council; b) those that are implemented in the framework of Gipuzkoa Lab with leadership from the Deputation of Gipuzkoa and c) those promoted by third parties—in other words, through an open call for aid. The selected projects obtained budgetary and technical resources with teams to achieve their objectives in various stages. The result of this interrelation between the public and private sectors is a portfolio of projects that can boost the reciprocal process of innovation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gipuzkoa Lab—authors’ elaboration.

In 2017, according to the Department of Governance and Communication of the Government of Gipuzkoa, the public policy laboratory had a total budget of EUR 720,000. In the framework of an open call for aid, the Gipuzkoa Lab has, so far, launched 58 projects. The following section discusses the methodological model and the achieved results of one particular call focused on workplace participation named “Gipuzkoa Lab Participation”.

5.3. Gipuzkoa Lab Participation Project

Gipuzkoa Lab Participation emerged as a pilot project in the framework of the Gipuzkoa Lab. The main objective of Gipuzkoa Lab Participation is to extract shared learning experiences that are relevant for companies, workers and the public sector in Gipuzkoa. The facilitation of worker participation in the companies of Gipuzkoa is based on the following objectives [50]:

- Increase the number of employees that participate in these companies and share successful participation models among them to improve their quality.

- Build a context that favours participation to improve communication and collaboration between different local institutional agents, work unions and academia, along with the Provincial Government.

- Facilitate and increase awareness among workers and employers about the importance of worker participation, compromise and the implications of these actions.

The generation of collaboration dynamics with institutional agents, businesses, unions and academic agents is key in promoting coordinated interdepartmental policy actions by the Provincial Council. These experiences have to be useful for other organisations of the province, which are looking to improve or are promoting the participation of their employees in their own organisations. Also, these experiences must work as inputs to re-adapt the policy actions implemented by the Provincial Council on this topic.

The specific objectives of this call are based on [51]:

- Facilitate the development of innovative projects in workplace participation.

- Foment the different levels of participation (management, results, and/or property).

- Favour the interaction and knowledge exchange between companies and experts in this field.

- Identify new actions form the Provincial Council to guarantee the sustainability of workplace participation.

According to the Director of Economic Development, Gipuzkoa Lab participation has had two different editions involving a sample of 20 different companies and 1500 people (see Table 3).

Table 3.

List of involved companies.

The selection of these companies was performed according to a series of different criteria related to their legal structure (cooperatives, labour corporations, commercial societies); their size (small, medium, big); sector (industrial, professional services); and level of experience in worker participation (beginner, intermediate or advanced).

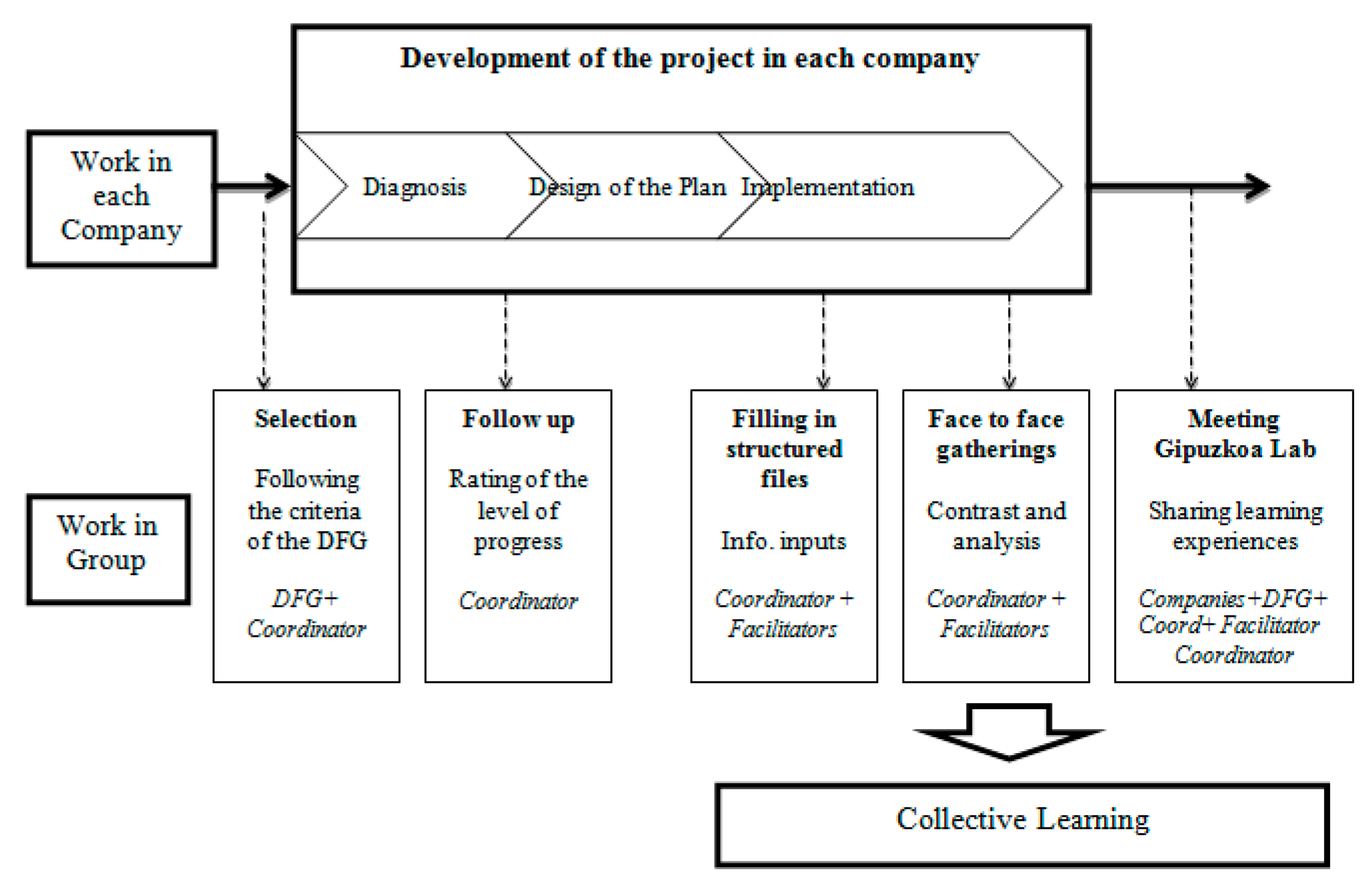

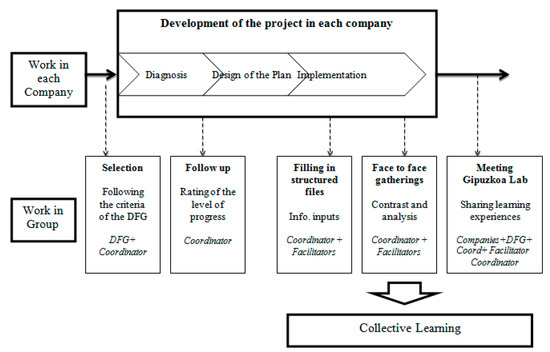

This project is based on a qualitative methodology using two processes (see Figure 2). First, in the diagnostic process, questionnaires were used to analyse the situation of worker participation based on different tools developed by consulting firms. The questionnaires were completed by the entire staff, workers or specific group (mainly the management team). Studies, publications and other materials were used in this field (e.g., contents available on the Gipuzkoa Participation website), workshops and training sessions. These tools allowed an in-depth analysis of the situations related to worker participation in the companies and the identification of lines of action to reinforce the participation model.

Figure 2.

Methodology Gipuzkoa Lab Participation—authors’ elaboration based on Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa [50].

Second, the design and implementation phase of the participation plan for each company received financial support from the Provincial Council. The knowledge of other participation experiences, interviews and group dynamics and, in some cases, the application of financial and fiscal incentives, were also used. These have been key factors in the development of the pilot projects.

Finally, all projects received financial support from the Provincial Council through an open call for aid or collaboration agreements with universities. This support is considered important for the hiring of experts, particularly for small businesses, because they have less capacity for this type of project.

6. Results—Gipuzkoa Lab Participation

According to the data collected, the companies that participated in this experimental project reached a consensus among all the involved parties (workers, facilitators and coordinators) and the public sector concerning the positive impact of worker participation in improving the wellness of employees, as well in strengthening competitive strategies in their working environments. During an interview with the Economic Development Director of the Gipuzkoa government, it was stressed that “promoting these business and social behaviours strengthens the sustainable generation of wealth in the territory and makes people the epicentre of business activity as a fundamental part of society”. On the other hand, some of these principles also apply to the organisation of work inside public sector institutions and public administrations, which implies that it will be necessary to co-create new public procurement frameworks to achieve and sustain some of the proposed policy actions inside the Gipuzkoa Lab. Moreover, all the stakeholders considered that workplace participation could help sharpen the grassroots development of these companies in the province.

This consensus was derived in the co-design of a series of preliminary learning objectives that were divided into two different dimensions—the first one linked to the internal and external management of companies and the public sector and the second one linked to the property of these companies.

Concerning the first dimension, during the interview, the Gipuzkoa Lab Manager reported the following learning objectives:

- Improvement of the labour climate and creation of a working environment that is more attractive.

- Increase the level of compromise, the implications and the sense of belonging.

- Achieve a better alignment of workers with the objectives/strategies of the company.

- Foment a greater autonomy and assumption of management responsibilities for the persons involved.

- Advance transparency and reinforcement bilateral communication and involvement in the decision-making processes.

- Encourage the professional and personal development of workers.

Regarding the second dimension, three aims were determined:

- Carry out the relay of the property (active or passive partners) and start preparing for future retirement.

- Avoid selling to third parties when facing the imminent retirement of the major owner.

- Favour the retention of talent within the organisation.

In order to achieve these objectives, in the words of the Gipuzkoa Lab Manager, “The interested parties agreed on a series of policy actions related to the way in which they manage information and communication inside the organisation, training, cultural heritage and internal governance, among other factors” (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Policy actions to achieve learning objectives.

On the other hand, the interviews were especially useful in identifying a series of possible barriers and drivers for the achievement of these policy actions observed inside companies and public sector institutions (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Main barriers and drivers for worker participation.

Finally, some of the key learning experiences were aligned around the need to reinforce worker participation in a very progressive manner, demanding more experimentation and awareness by workers and smaller companies and a progressive and ordered delegation of responsibilities. The periodical reinforcement of participation in management was also a significant issue. According to the Economic Development Director of the Gipuzkoa government, “There is a need to revise the management structure, the dynamics and systems of information and communication, and their influence on decision-making processes, especially in cooperatives and labour societies. The adaptation of best practices developed by other companies in this particular arena is also important”.

Likewise, the elaboration of a collective diagnosis of the situation through different questionnaires, individual interviews or focus groups of key organisational actors was a relevant issue. This matter was very closely related to the institutionalisation of a participatory culture that would involve all the stakeholders in the process of design, decision-making and implementation in the initial stages of the policy programs. This was seen as a vital condition for the acquisition of shared compromises between different actors in policy action development.

Overall, considering these results, we argue that this public sector innovation laboratory has been an effective space to facilitate governance and collaboration between relevant and affected stakeholders [18]. We can also demonstrate, from a practical perspective, how public innovation laboratories can contribute to more collaborative governance through the promotion of actions that are considered a fundamental axis in the creation of empowered citizenship as an agent of social change and a leader in the construction of democracy and local development.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The public sector is a dynamic system, and, as such, it needs to be managed in order to maintain its competitiveness, since the sector is increasingly under pressure to provide new public services with scarce resources [52]. In this framework, the influence of contextual factors in which the public sector operates plays an important role and aspects such as culture and organizational conditions can influence its innovation processes and facilitate or impede this work [53]. Precisely, one of the most important aspects of public innovation labs is the level of organizational autonomy, as this autonomy allows these spaces to pursue discontinuous and disruptive innovations without the direct interference of traditional organizational structures [11]. Labs arise as small and dynamic entities with relative independence and greater space for failure than traditional organisms [54].

This particularity allows the public sector to organize to support the generation of new ideas, transforming them into products and services demanded and tested by the citizens and agents involved in facilitating their introduction to the market [55]. In other words, this space allows people to organize more effectively by efficiently exploring new ideas and opportunities that help produce models and instruments to generate social policies and public value actions [13].

In an attempt to make a contribution to policy science or public management literature, this article has introduced policy innovation labs as emerging knowledge actors in collaborative governance. We have explored the role played by policy labs in regional development and how they help create a more collaborative public sector and better public–private cooperation, thereby generating a relationship of mutual enrichment with citizens, where new public and social value are generated inside and outside the system [6,9].

According to Emerson and Nabatchi [56], researchers are seeking to understand these new collaborative dynamics, while public sector practitioners are looking to improve their collaborative efforts. In this sense, the practical experience described in this paper provides insight into introducing this approach in a regional context. This study also analyses the results of testing proposals and solutions as a way of contributing to the policy process. From an analytical perspective, this public-sector practice also presents challenges in relation to the practical implementation of collaborative governance in policy processes and outcomes. Thus, it is important to highlight that the political institutionalisation of public sector innovation and collaborative governance as a standardized action framework is an arduous and complex task since its results are not immediate and the process of training and learning its different expressions is slow and costly, as it requires resource or service conditions, policy/legal frameworks, socioeconomic and cultural characteristics, political dynamics and power relations [56]. If we add to these factors problems such as the hierarchical and bureaucratised structures of the public sphere and the necessary updating of its human and technological resources, this transformation becomes even more complex.

Nevertheless, in this complex context, public innovation labs emerge as spaces that can solve these issues. Having a holistic view of challenges can foster ecosystems that catalyse collective intelligence, generate new routines within public services and create platforms to develop and promote participation, thereby contributing to the development of collaborative governance through partnership actions that can contribute to public service and policy. They can prototype places for collaboration and co-creation that may improve the lives of citizens. This is a very important condition for promoting collaborative governance; the principle of engagement is a dynamic process that occurs with the creation of common interaction spaces in which different agents participate in working collaboratively and creating value for local development [5].

Furthermore, applying dynamics based on design and innovation is already challenging in itself; how we integrate the knowledge of experts traditionally included in these dynamics towards design-based practices is not an easy question to answer. Perhaps the most pressing challenge facing these types of perspectives is the imbalance between the power and the knowledge that is generated between, on the one hand, the actors, agents and institutions that hold power and, on the other hand, the civil organizations and users—that is to say, between the expert knowledge coming from actors and agents more or less institutionally legitimized (academic institutions, political advisors and experts of various kinds) and the tacit knowledge coming from citizens. In this respect, Sanders [43] distinguishes between an “expert mindset” and a “participatory mindset”. An expert mindset refers to the idea that users are subjects and reactive informers; the participatory mindset is the practice where users are partners and active co-creators [44]. This imbalance can affect the achievement of realistic results because the knowledge coming from the “bottom-up” structures is often not integrated into more general management dynamics or is simply lost along the way.

On the other hand, creating new and better solutions generates new demands that public administrations must adapt to and face. Each socio-political context responds to different needs. There are also great difficulties in measuring and monitoring the impact of the implemented actions, as well as a limited ability to develop long-term sustainable initiatives and strategies. So far, Gipuzkoa Lab has been based on experimentation approaches that were materialised in key pilot projects. How these projects will be sustained in the future and how exactly some of their outputs will be scaled for the formulation of new public policies remains to be seen. These issues often arise through the shifts in power relations inside the government, which usually have a great impact in the future sustainability of policy measures by the new political parties in office.

Moreover, the adoption of design methodologies for the transparent, effective and efficient use of public resources does not face the challenges that will affect public organisations in the future of work and the workplace. That is to say, how exactly do we train and update the skills of civil servants to be competitive in a rapidly changing working environment when public organisations are still constrained by bureaucratic measures and hierarchical procurement frameworks? If these measures and the impact of rapid technological and digital change require more specialised knowledge inside organisations, what will be done with the surplus of public workers in the future. The pressure to reinforce workplace innovation and the future of work is something that also has to be taken very seriously inside public sector organisations. Fully engaging public sector staff in improvement and innovation involves more than an isolated management initiative or programme; it involves the introduction of empowering work practices and procedures at every level, from day-to-day operations to strategic decision making [57].

In this sense, concerning some of the measures and the learning experiences adopted in Gipuzkoa Lab Participation, there is still a lack of clarity on how exactly these recommendations will be applied to improve workplace participation in public sector institutions, especially when facing the barriers that are created by departmental silos and internal and external distrust within different governance levels. This is also applicable to the private sector but the lack of public procurement to guarantee the free and open diffusion of knowledge and information inside public organisations is still a pending task. The impact stakeholders can have on organisational policies, strategies and projects is dependent on their relationship to the organisation itself, the issues of concern or both [58].

8. Limitations and Future Directions

Since every research project has its limitations, this one is no exception. Based on the analysed experience, the first limitation is the absence of a comparative analysis with other experiences, which could reinforce the evidence for the effectiveness of developing public innovation laboratories, through which changes within governments can be accelerated and promoted. Secondly, one of the limitations of this study is that the qualitative results of the analysis take into account the perceptions of the companies participating in the laboratory. It is essential to be able to develop a measurement of impacts in the short, medium and long term that provide more in-depth evidence of the potential and effects of implementing these types of projects within governments.

In relation to the laboratory itself, one of the fundamental aspects that is addressed as a challenge is the sustainability of these types of spaces. Changes in the government’s strategy can negatively affect the participation of citizens in the processes of experimentation, transparency and democracy, as collaborative governance depends, to a large extent, on the ability of governments to make their initiatives sustainable in the long term. On the other hand, it will be important to analyse these difficulties to connect with citizens in a way that allows the public to fully understand the purpose of this governance model.

Therefore, future analyses must focus their attention on these challenges and limitations. Developing a panel of indicators to investigate the effects of innovation labs in the public sector is something that future research can explore, since governments, multilateral bodies, innovation centres and academia could benefit from methodologies that support the promotion and evaluation of these participation and governance models that are growing exponentially in cities and regions. Finally, but no less importantly, an analysis of the influence of regional context and social and institutional fabric on successful implementation is also required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.U.; X.B.; N.R. Method and data analysis, A.U. and X.B. Writing, A.U.; X.B.; N.R. Review and editing, A.U.; N.R. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kooiman, J. Modern Governance: New Government-Society Interactions; Sage: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, S.P. The New Public Governance: Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Torfing, J.; Peters, B.; Pierre, J.; Sørensen, E. Interactive Governance: Advancing the Paradigm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bason, C. Leading Public Sector Innovation: Co-Creating for a Better Society; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2011, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bason, C. Discovering co-production by design. In Public and Collaborative: Exploring the Intersections of Design, Social Innovation and Public Policy; Manzini, E., Staszowski, E., Eds.; DESIS Network: Milan, Italy, 2013; pp. viii–xx. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. Ready or Not? Taking Innovation in the Public Sector Seriously; NESTA: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E.; Staszowski. Public and Collaborative: Exploring the Intersection of Design, Social Innovation and Public Policy; DESIS Network: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bason, C. Design for Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Puttick, R.; Baeck, P.; Colligan, P. i-Teams: The teams and Funds Making Innovation Happen in Governments Around the World; NESTA: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tõnurist, P.; Kattel, R.; Lember, V. Innovation labs in the public sector: What they are and what they do? Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 1455–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Observatory of Public Sector Innovation. Available online: https://oecd-opsi.org/ (accessed on 23 July 2019).

- Williamson, B. Governing methods: Policy innovation labs, design and data science in the digital governance of education. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 2015, 47, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGann, M.; Blomkamp, E.; Lewis, J.M. The rise of public sector innovation labs: Experiments in design thinking for policy. Policy Sci. 2018, 51, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, M.; Lochard, A. Public Policy Labs in European Union Member States; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo, S.; Dassen, N. Innovation for Better Management: The Contribution of Public Innovation Labs; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Robinson, D.G. The New Ambiguity of ‘Open Government; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, H.V.; Bason, C. Powering collaborative policy innovation: Can innovation labs help. Innov. J. Public Sect. Innov. J. 2012, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Demircioglu, M.; Audretsch, D. Conditions for innovation in public sector organizations. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieboom, M. Lab Matters: Challenging the Practice of Social Innovation Labaroratories; Kennisland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The new public sphere: Global civil society, communication networks, and global governance. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2008, 616, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offe, C. La Gestión Política; Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. La Globalización. Consecuencias Humanas; Fondo de Cultura Económica: México, D.F., Mexico, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, J. Governance. A social-political perspective. In Participatory Governance; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. The rise of governance and the risks of failure: The case of economic development. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1998, 50, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R. The new governance: Governing without government. Political Stud. 1996, 44, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, P.; Loveridge, S. Toward an understanding of types of public-private cooperation. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2002, 26, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.; Barnes, M.; Sullivan, H.; Knops, A. Public participation and collaborative governance. J. Soc. Policy 2004, 33, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Torfing, J. How does collaborative governance scale? Policy Politics 2015, 43, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, V.; Edelenbos, J.; Steijn, B. Innovation in the Public Sector; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Albury, D. The Innovation Imperative; NESTA: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J.L.; Camus, A.; Jetté, C.; Champagne, C.; Roy, M. La Transformation Sociale par L’innovation Sociale; Presses de l’Universite du Quebec: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.H. Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Bloomberg, L. Public value governance: Moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Adm. Rev. 2014, 74, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.; Sancino, A.; Benington, J.; Sørensen, E. Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C. The networked polity: Regional development in Western Europe. Governance 2000, 13, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Theories of Democratic Network Governance; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.M. The future of network governance research: Strength in diversity and synthesis. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, J. Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hippel, E. Democratizing Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-Des. 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, R.; Farrington, C. Quantified Lives and Vital Data; Springer: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. Worker Participation: Current Research and Future Trends; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2005; pp. xi–xxiii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeij, P.R.; Dhondt, S. Theoretical Approaches Supporting Workplace Innovation. In Workplace Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandiaran, X.; Luna, A. Building the future of public policy in the Basque Country: Etorkizuna Eraikiz, a metagovernance approach. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa. Plan Estratégico de Gestión 2015–2019 de la Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa; Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa: San Sebastián, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa. Experimentation Methodology of Gipuzkoa Lab; Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa: San Sebastian, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa. Experimentation in Participation within Gipuzkoa Lab; Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa: San Sebastian, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa. PARTAIDETZA Programme; Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa: San Sebastian, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, T.; Demircioglu, M.; Alsos, G. Intensity of innovation in public sector organizations: The role of push and pull factors. Public Adm. 2019, 97, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, A.; Casali, L.; Hollanders, H. How European public sector agencies innovate: The use of bottom-up, policy-dependent and knowledge-scanning innovation methods. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Grandinetti, R. Laboratorios de Gobierno Para la Innovación Pública: Un Estudio Comparado de las Experiencias Americanas y Europeas; RedInnolabs: Rosario, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.; Lehmann, E.; Licht, G. National systems of innovation. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T. Collaborative Governance Regimes; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Totterdill, P. Introducing Workplace Innovation in the Public Sector; European Institute of Public Administration: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://www.eipa.eu/introducing-workplace-innovation-in-the-public-sector/ (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Acland, A. Dialogue by Design: A Handbook of Public and Stakeholder Engagement; Dialogue by Design: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).