1. Introduction

As the current market environment among companies tends to shift from product-oriented to service- and customer-oriented, the importance of customer management through creating positive customer value is further emphasized [

1]. Effective salespeople play key roles in creating positive customer value by fostering sustainable relationships between customers and firms [

2]. These behaviors contribute to the sustainable benefits of their companies as well as positive relationships with customers.

A salesperson plays an important role in representing his or her company in the liberal market economy. Their role is even more critical in representing their firm when the company’s products are not particularly superior. A salesperson is also a key factor in delivering corporate images to customers [

3,

4,

5]. The salesperson is the contact point for customers to quickly identify changes in their needs, acquire and utilize customer information, and provide services and products that meet the customers’ expectations, except when there exists a purchase facilitator such as a digital signage and a different shopping characteristics [

6,

7,

8]. The salesperson not only increases customer satisfaction but also superior sales performance in a sustainable way [

9,

10].

Previous studies have been conducted since the 1960s to improve the salesperson’s performance and to explore what is needed for effective sales. As a result, many studies have shown that it is possible to improve the performance of salespeople through monetary rewards, such as incentive and salary increases [

11], and welfare provisions [

12] and non-monetary rewards, such as education, training, and communication [

13]. However, there are other studies that suggest that if a salesperson is not able to provide good customer services, he will feel exhausted and emotionally unstable [

14]. As such, monetary or non-monetary rewards alone cannot improve the performance of the salesperson. Thus, more recent studies focus on customer orientation and adaptive selling as resources of effective and sustainable sales.

According to previous research, sustainable behaviors have been defined as a set of actions to protect natural, social, and human resources [

15]. In marketing strategy and sales domains, marketing orientation or customer orientation is a philosophy and an action plan that focuses on long-term business relationships. Companies conducting a coherent set of behaviors which focuses on their B2B partners find that a solid business entry barrier can be created by their satisfied clients. Furthermore, in the B2C market, brand loyalty can be strengthened by meeting the market needs, and all these efforts ensure sustainability when managing core business activities.

In the marketing field, as relationship marketing was highlighted, one began to pay attention to how to maintain and promote long-term relationships with existing customers rather than short-term sales-oriented relationships with new customers. The term, relationship marketing, was first mentioned in the literature of Berry [

16], and since then, much has been discussed about relationship marketing in the service marketing literature. This relationship marketing has been more effective in the service industry when there is a high orientation towards customers and salespeople interact closely with customers in order to benefit from short-term exchanges [

4].

Definitions of relationship marketing may vary, but the concept of relationship marketing is the same as pursuing mutual benefits that seek long-term relationships between customers and companies. Morgan and Hunt [

17] defined relationship marketing as the first line of marketing activities carried out to form, develop, and maintain successful relationship exchanges, while Treacy and Wiersema [

18] emphasized a company's sustainable competitive advantage and customer value. For this, they argued that customer intimacy, product leadership, and differentiation were necessary. Several studies directly investigate this influence of relationship marketing on business sustainability [

19,

20]. In sum, the main purpose of relationship marketing is to maximize mutual benefits between customers and companies by having a long-term and sustainable relationship with customers.

Customer orientation is one of the major concerns to maintain a long-term relationship with customers. Salespeople focus on customers’ needs and desires and deliver relevant services. They acquire customer information and knowledge, deliver services to satisfy their customers’ needs and desires, and develop products and company knowledge [

21]. Several previous studies found that customer orientation affected performance of salespeople in a significant way. It also had an effect on salespeople’s behaviors in relational sales environments [

22].

Adaptive selling is the ability of a salesperson to change his sales behavior while interacting with customers [

23], or based on perceived information about the nature of sales situations such as correcting communication styles, content, and sales behaviors [

24,

25]. In other words, adaptive selling modifies sales behaviors to meet the individual needs of customers, which strengthens the relationship between the customer and the salesperson, resulting in a significant impact on the sales performance [

26].

This study of customer orientation and adaptive selling argues that these sales behaviors are formed by the characteristics of organizations and the psychological characteristics of the individual salesperson and directly affect the sales performance [

22,

26,

27]. However, research on the difference between customer orientation and adaptive selling for the salesperson is insufficient, and the two concepts tend to be considered as identical.

In terms of the differences between the two concepts, customer orientation is an organization culture that creates the most effective and efficient actions necessary to create a superior value to customers [

28], while adaptive selling can be seen as the salesperson’s individual actions to perform marketing concepts [

29]. In other words, customer orientation can be regarded as a culture composed of values or beliefs shared by the organizations. This leads to the salesperson’s behavior, whereas, adaptive selling can be regarded as the salesperson’s individual decision making action.

Recently, studies on enhancing the relationship between salespersons and customers are emerging, not only in the existing B2B field, but also in B2C research. In Franke and Park's study [

30], a meta-analysis was conducted in relation to sales behavior and customer orientation of salespersons. In the sample used for the meta-analysis, they included 31,428 salespeople from 33 different journals, 48 dissertations, and six working papers. The representative samples of salespeople are from telemarketing, door-to-door, computer services, financial services, insurance, real estate, etc. From this perspective, if the salesperson can have more customers by enhancing relationships with them, they can increase sales. This is an important finding, in that salespeople can control their company's unilateral dismissals or opportunistic behaviors by securing a large number of customers through enhanced customer relationships.

Hurley and Hult [

31] proposed a causal relationship between an organizational culture and individual behaviors, in the sense that the culture of the organization affects individuals’ behaviors (values-drive-behavior). Deshpande and Webster [

29] argued that an organizational culture shapes shared organizational values and beliefs and provides individuals with a basis for taking actions within the organization. However, Kohli and Jaworski [

28] argued that specific behaviors of individuals transforms marketing concepts in practice and such concepts were applied to organizational knowledge assets of the salespeople (behavior-drive-values).

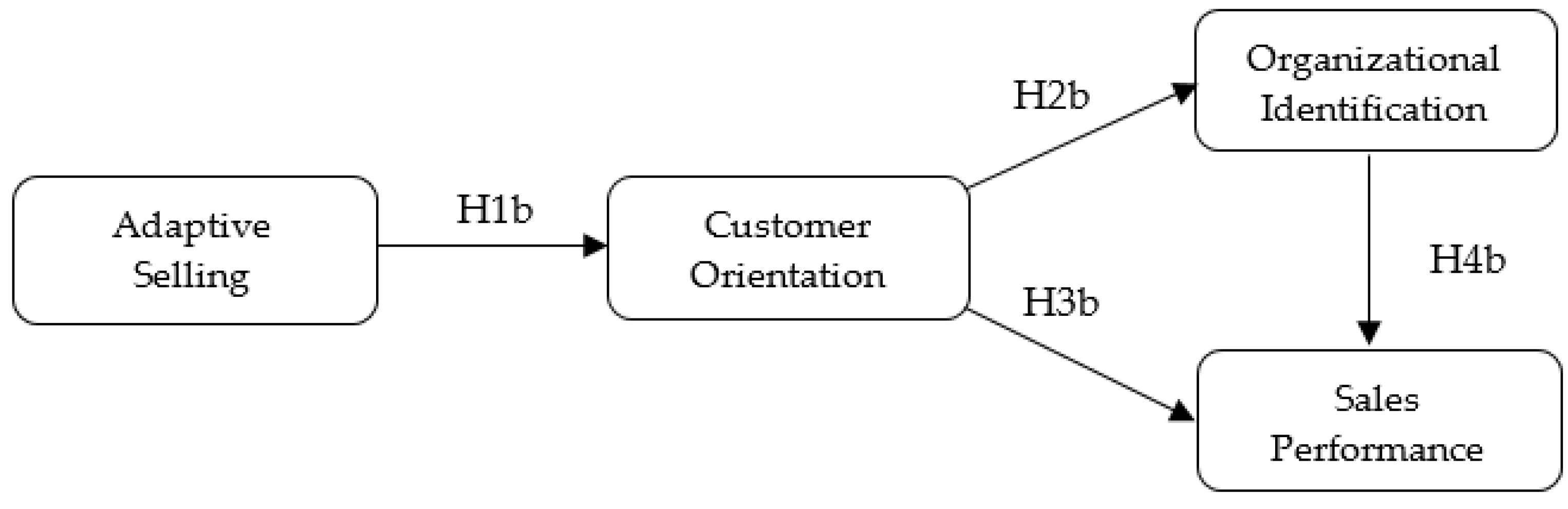

Based on previous studies, the purpose of this study is as follows. In this study, we investigate whether customer orientation as a norm of an organizational culture affects an individual’s sales behavior which reflects individual characteristics (culture-drive-individual behavior) or whether an individual’s sales behavior with salespeople’s characteristics affects customer orientation as an organizational concept (individual behavior-drive-culture). Based on these parallel constructs, two relational models will be theoretically discussed and empirically tested. The study will provide implications on sustainable business profits and sustainable relationships with customers in the future.

5. Discussions and Conclusions

This study examines the customer orientation and adaptive selling of salespeople in terms of organizational viewpoint and the behavioral aspect of individual performing marketing concept, and the relationship between two variables is summarized as follows. First, as a result of examining the causal relationship between customer orientation and adaptive selling, Research Model 1, in which customer orientation is preceded by adaptive selling, is statistically significant, and customer orientation has a positive effect on adaptive selling (H1a). Second, adaptive selling had a positive effect on both organization identification (H2a) and sales performance (H3a). Finally, organizational identification does not have a significant effect on sales performance (H4a).

Previous research on salesperson’s customer orientation and adaptive sales has focused on the preceding or outcome factors affecting both variables. However, this study focused on identifying relational constructs between salesperson’s customer orientation and adaptive sales. In an existing study of the relationship between two variables, Spiro and Weitz [

24] argue that customer orientation has a positive effect on adaptive sales, while Franke and Park [

30] suggest that adaptive sales can increase customer orientation. It has been demonstrated that the effect of customer orientation on adaptive sales is not clear from the studies. This study, however, focused on identifying precedent and subsequent relationship between the two variables. The relationship between customer orientation and adaptive sales of salespersons was distinguished in terms of behaviors and individual behaviors as an organizational culture. As a result, a statistical significance of organizational behavior affecting individual behavior has been found. Therefore, the study firstly initiates the causal relationship between customer orientation and adaptive sales and opens the black box of how customer orientation in corporate level implements an individual salesperson’s adaptive motivation.

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Our study shows that customer orientation and adaptive selling are resources of sustainable companies’ performance. Based on the result, the current study has contributed in several ways.

First, the study examined the relationship between customer orientation and adaptive selling in terms of organizational culture and individual behavior. Although there have been many studies investigating the effect of customer orientation and adaptive selling on sales performance, no significant relationship between these two variables has been found. Therefore, this study is meaningful in identifying the consequential relationship between customer orientation and adaptive selling.

Second, the sales behavior of the salesperson shows that the customer orientation that is driven by the organizational culture affects the individual’s sales behavior rather than that the individual’s sales behavior affects the organizational culture. It shows the same perspective of previous studies [

29], that organizational culture influences individual behavior (culture-drive-individual behavior). It can be said that a salesperson can do adaptive selling well even for a variety of customers’ anomalous requests if companies have a good organizational culture that focuses on customer satisfaction and building sustainable customer relationship. Through this, the companies will be able to make sustainable profit. Therefore, it is important to cultivate customer-oriented culture through educational programs before the salesperson starts to take customer-oriented actions.

Third, adaptive selling is an act of persuading customers at the contact point with customers, and responds to customers’ anomalous behaviors and attempts to share positive aspects of sales products or companies. Therefore, it is commonly accepted that adaptive selling can increase organization identification with higher company attachment level by observing salesperson’s own behavior [

94]. It is important for the company to give the salesperson empowerment to make decisions at the point of contact with the customer.

Fourth, adaptive selling affects sales performance as a sales strategy that identifies the needs of consumers at the point of sales in order to improve short-term performance. Adaptive selling varies depending on the individual’s ability or characteristics. The company has various supports to develop the ability and characteristics of the individual through education and self-development of the sales skill, so that the salesperson can respond properly at the point of contact with the customer.

5.2. Limitation and Future Research

Limitations of this study and directions for future research are as follows.

First, it is difficult to generalize the findings of this study to other industries, such as the manufacturing industry, because in the current study we only focused on the service industries. Therefore, in future research, it is meaningful to investigate the differences between B2B and B2C industries in order to give specific insights to each field or increase the external validity of the results.

Second, there are various leading factors and output factors that can affect both customer orientation and adaptive selling. In particular, previous studies related to the two sales behaviors discussed that customer orientation or adaptive selling are constructed by organizational characteristics or psychological characteristics of an individual salesperson and directly affect sales performance [

22,

26,

27]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore a few more variables among these characteristic variables and to incorporate them to the current research model.

Finally, considering the causal relationship between the variables in the study, it is necessary to make a longitudinal measurement of the performance variable of adaptive selling and customer-oriented selling. In addition, the performance was measured in a self-reporting manner, therefore, we argue that future studies should use alternate methods to minimize the self-reporting bias.