Social Acceptability of More Sustainable Alternatives in Clothing Consumption

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Efficiency: Minimize the input of resources (land, energy, raw materials) to produce the consumer good and use it intensively.

- Consistency: Substitute resources and adapt production processes to natural resource flows to produce products in a more environmentally friendly manner.

- Sufficiency: Restrict consumption to a level that is enough for a healthy and satisfactory life but avoids excess.

- prolonging of the useful lifetime of clothing, e.g., by choosing high-quality garments, by repairing shopworn clothes, by upcycling of used clothes or by passing them to others;

- buying of timeless instead of voguish clothing, more sustainably produced clothing, second-hand instead of new clothes, or clothing made from recycled parts or fibers;

- sharing, swapping, lending, renting, or leasing of clothing instead of buying it;

- laundry with reduced temperatures and environmentally compatible detergents;

- consigning sorted out clothes to recovery.

- The main motives for the purchase of clothes are replacement needs (28.1%), desire for something new (17.5%), special offers (16.0%), and impulse buying (12.5%) (Germany [18]).

- There are practically no differences between different consumer segments with respect to the time clothes are kept before being discarded and the frequency of wearing each clothing item (Germany, Poland, Sweden, U.S.A. [15]).

- Only 21% of the consumers sort out clothing solely because it is worn out or does not fit anymore (Germany [17]).

- For about 40% of German consumers, social and environmental compatibility of the production of clothing are relevant buying criteria (Germany, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain, [19]).

- The percentage of consumers buying clothes made from organic materials increases with income, i.e., it increases from the low-budget to the high-premium consumer segment (Germany, Poland, Sweden, U.S.A. [15]).

- The willingness to buy clothes produced under environmentally and socially acceptable production conditions is higher among women compared to men and increases with age (Germany [17]).

- The value consumers attribute to second hand-clothing and clothing made of recycled material is lower than for conventional clothing. Compared to clothing made of conventional materials, that made of organic materials is rated higher in the high casual and premium consumer segments but lower in the low-budget and low-casual segments (Germany, Poland, Sweden, U.S.A. [15]).

- For less than 10% of the consumers, the buying of second-hand clothing is a real option (European Union [20]).

- The buying of second hand-clothing is more widespread among women compared to men and can be found more frequently in younger than in older population segments (Germany [17]).

- Biospheric and altruistic values have a positive effect, while egoistic and hedonic values have a negative effect on attitudes towards more sustainably produced clothing (Germany; 1085 female consumers with a certain openness to the purchase of sustainable clothing in the middle- to high-prize segment [30]).

- The consideration of sustainability criteria in buying decisions for clothes is positively influenced by biospheric values and the feeling of compassion for vulnerable others, while there is a negative relation to hedonic values (Germany; 981 consumers all from the same small town [31]).

- Altruistic values have a positive effect on attitudes towards collaborative fashion consumption and the corresponding behavior. The association with egoistic values is slightly negative. There is also a negative effect of age on the behavior. All effects are quite small (1014 consumers all from the same small town [32]).

- There is a positive relation between personal norms and the intention to not consume clothing deemed problematic and to consume less clothing. The personal norms are associated with problem awareness, ascription of responsibility, and outcome efficacy (USA, Germany, Sweden, Poland; 4591 consumers from the general population [33]).

- Anticipated guilt is a major driver for fair-trade buying behavior (USA; 430 consumers [34]).

- Fashion leadership is positively associated with the intention to participate in clothing renting and swapping. The same relation can also be found for the need for uniqueness and the swapping intention. Materialism is negatively related to both renting and swapping (35: USA; 431 females [35]).

- (1)

- Are there social differences with respect

- (a)

- to the expression of attitudes and the relevance of social norms related to clothing consumption and

- (b)

- the consumption behavior and the openness to more sustainable alternatives?

- (2)

- Which factors have the strongest influences

- (a)

- on the consumption behavior and the use of clothing in general and

- (b)

- on sustainable clothing consumption supporting behaviors?

2. Materials and Methods

- personal importance of fashion and clothing;

- buying, duration of use, and reasons for the sorting of clothes;

- motives and reasons for purchase decisions;

- attractiveness of consumption alternatives;

- attitudes towards more sustainably produced and second-hand clothing;

- problem awareness related to clothing production and consumption;

- general sustainability-related attitudes.

3. Results

3.1. Attitudes and Social Norms

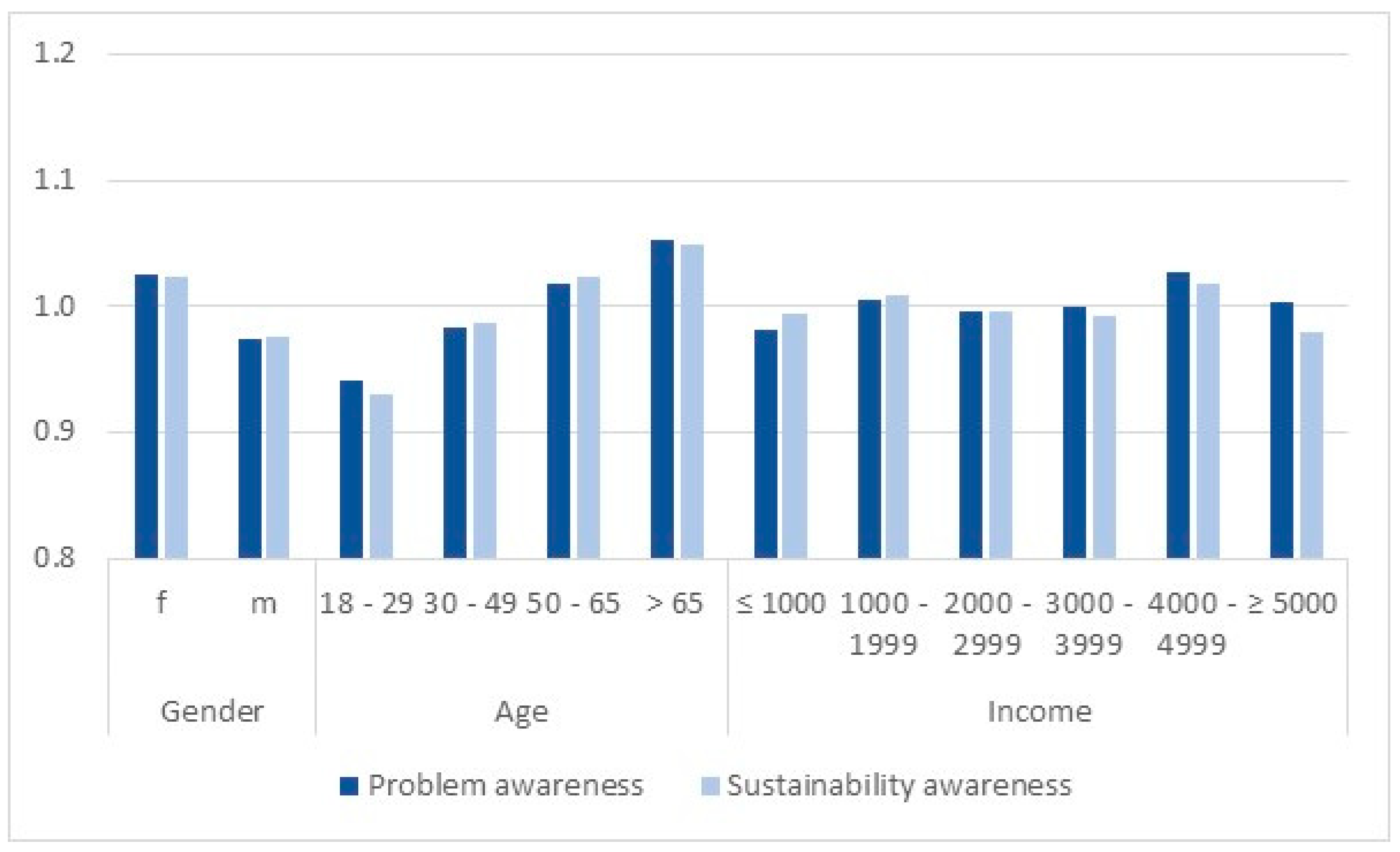

3.1.1. Sustainability and Problem Awareness

- For me, an intact environment is essential for a good life (rates of agreement on the two/three highest stages of a 6-level rating scale: 73.2%/91.1%).

- It means a lot to me to live in such a way that the environment is harmed as little as possible (agreement: 69.5%/91.0%).

- It is imperative that all people in the world have similarly good living conditions (agreement: 70.5%/89.8%).

- It is important to me to behave in such a way that the lives of other people are not impaired as far possible (agreement: 72.3%/91.9%).

- Environmental pollution by the mass production of clothing (rates of classifications on the two/three highest stages of a 6-level problem rating scale: 55.9%/84.1%);

- Bad working conditions in the clothing industry (64.2%/85.8%);

- Toxic substances in clothes that could harm health of wearers (62.1%/84.3%).

3.1.2. Secondary Function of Clothing

- Distinction

- I want to show by my clothing that I belong to a certain group of people (agreement: 17.8%/38.8%).

- By my clothing, I want to set myself apart from others (agreement: 22.7%/45.1%).

- Creativity

- For me it is fascinating to slip into new roles with different clothes again and again (agreement: 22.1%/44.5%).

- As for my clothing, I’m always looking for new ideas (agreement: 25.2%/51.9%).

- Individuality

- With the choice of my clothes I underline my personality (agreement: 47.3%/70.0%).

- I have my own style and choose what suits me from the respective fashion (agreement: 60.8%/88.2%).

- My clothing must please myself—I don’t care what others say (agreement: 70.6%/92.2%).

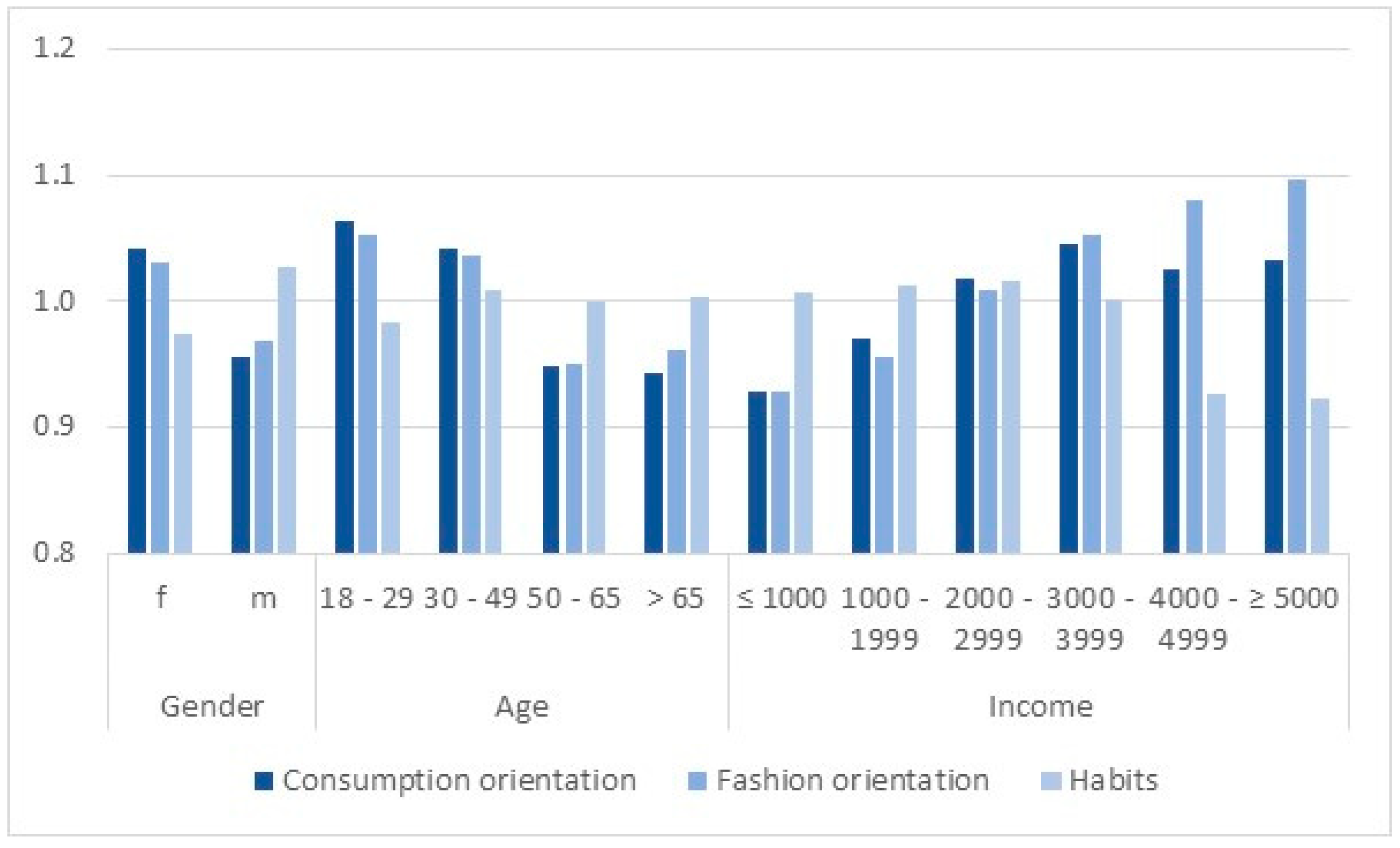

3.1.3. Consumption and Fashion

- Fashion orientation

- In fashion, I am often one step ahead of others (agreement: 14.7%/31.2%).

- In fashion, I know exactly what is ‘in’ and what is ‘out’ (agreement: 19.7%/44.4%).

- Usually, I wait until a new fashion comes out on top before I wear it (rates of disagreement on the two/three lowest stages of a 6-level rating scale: 17.7%/38.9%).

- I do not take part in this whole fashion rigmarole (disagreement: 9.2%/21.0%).

- When buying outerwear, it is important that it matches the current fashion trend (agreement: 27.8%/57.6%).

- Consumption orientation

- Buying clothes is great fun for me (agreement: 35.8%/64.0%).

- I like to go on shopping tour with others (agreement: 24.5%/45.2%).

- I regularly clear out my wardrobe to make room for new things (agreement: 20.8%/50.6%).

- I often buy clothes that I practically do not wear anymore afterwards (agreement: 11.2%/27.8%).

- I often buy clothes impulsively, without thinking about it for a long time in advance (agreement: 41.8%/67.7%).

- Habits

- I do not like changes in my clothing, I prefer to stick to my habits (agreement: 33.3%/65.9%).

- Usually, I wait until a new fashion comes out on top before I wear it (agreement: 23.5%/58.7%).

3.1.4. Social Norms

- Wearing time

- Most people who are important to me keep and wear their clothes for a long time (agreement: 38.1%/76.1%).

- Most people who are important to me would appreciate if I wear my clothes for a long time (agreement: 26.5%/64.5%).

- Sustainably produced clothing

- Most people who are important to me wear sustainably produced clothing (agreement: 14.4%/41.9%).

- Most people who are important to me would appreciate if I wear sustainably produced clothing (agreement: 24.1%/58.3%).

- Second-hand clothing

- Most people who are important to me wear second-hand clothing (agreement: 8.8%/22.9%).

- Most people who are important to me would appreciate if I wear second-hand clothing (agreement: 10.7%/33.5%).

3.1.5. Price and Quality

- Price consciousnessWhen buying outerwear, how important is it to you that

- it does not cost too much (rates of classifications on the two/three highest stages of a 6-level importance rating scale: 56.0%/85.6%);

- the price–performance ratio is right (97.0%/95.1%).

- Quality orientationWhen buying outerwear, how important is it to you that

- it consists of high-quality material (53.3%/84.1%);

- it is well made (78.5%/94.5%).

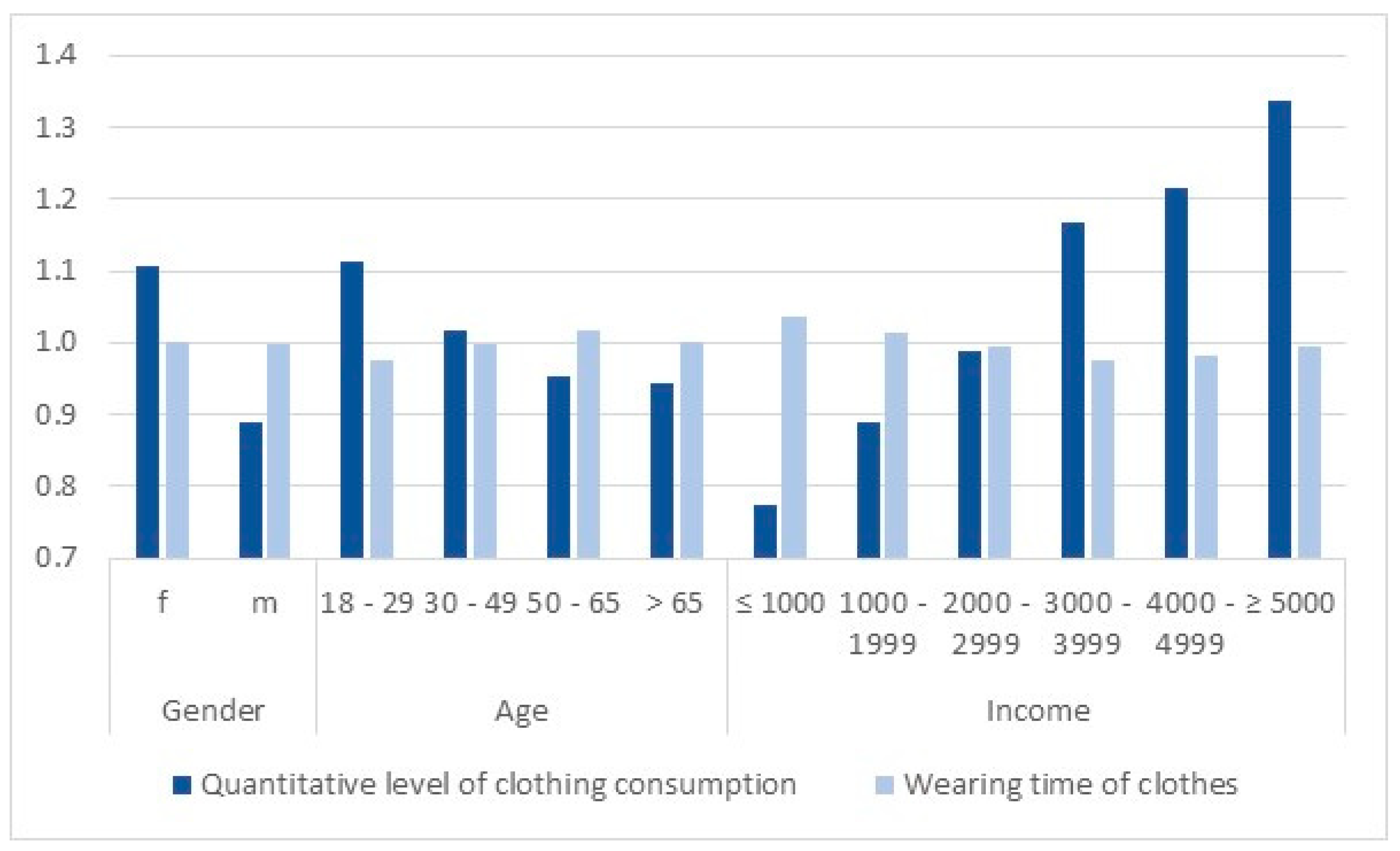

3.2. Consumption Behavior

3.2.1. Consumption and Lifetime of Clothing

- the quantitative level of outerwear consumption, calculated from the number of items bought in the last year, weighted by rough factors for the respective resource input and expenditures in manufacturing [2];

- the average wearing time for the same types of garment.

3.2.2. Sustainable Clothing Consumption Supporting Behaviors

- Restriction of clothing consumption

- I try to get along with as little clothing as possible (agreement: 26.2%/55.3%).

- I only buy clothes if I really need them (agreement: 42.7%/69.4%).

- Purchase of more sustainably produced clothingHow often do you use the following offers and possibilities in connection with clothing?

- buy clothing manufactured environmentally friendly (often: 9.8%, occasionally: 49.9%);

- buy clothing manufactured under fair labor conditions (often: 12.1%, occasionally: 56.2%).

- Purchase of second-hand clothingHow often do you use the following offers and possibilities in connection with clothing?

- buy second-hand clothing (often: 5.9%, occasionally: 35.0%).

3.3. Attitudes, Norms, and Behaviors

4. Discussion

4.1. Sufficiency

4.2. Consistency

4.3. Efficiency

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kleinhückelkotten, S.; Neitzke, H.P. Increasing sustainability in clothing production and Consumption—Opportunities and constraints. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2019, 28, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhückelkotten, S.; Neitzke, H.P.; Schmidt, N. Bewertung der Nachhaltigkeit von Innovationen Entlang der Textilen Kette; InNaBe-Projektbericht 7.1; ECOLOG-Institut: Hannover, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S. Environmental and social impact of fashion: Towards an eco-friendly, ethical fashion. Int. J. Interdiscip. Multidiscip. Stud. 2015, 2, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Muthu, S.S. (Ed.) Sustainability in the Textile Industry; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhückelkotten, S. Suffizienz und Lebensstile. Ansätze für eine Milieuorientierte Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation; Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spengler, S. Sufficiency as Policy: Necessity, Possibilities and Limitations of a Political Implementation of the Sufficiency Strategy; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schäpke, N.; Rauschmayer, F. Going beyond efficiency: Including altruistic motives in behavioral models for sustainability transitions to address sufficiency. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2014, 10, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B.; Glomb, M.; Hübner, G.; Kleinhückelkotten, S.; Landsbek, B.; Nebel, K.; Neitzke, H.P.; Schaltegger, S.; Woznica, A. Slow Fashion: Gestalterische, Technische und Ökonomische Innovationen für Massenmarkttaugliche Nachhaltige Angebote im Bedarfsfeld ‘Bekleidung’; InNaBe-Schlussbericht; ECOLOG-Institut: Hannover, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, J.; Laursen, S.; Rodríguez, C.; Bocken, N. Well Dressed? The Present and Future Sustainability of Clothing and Textiles; University of Cambridge, Institute for Manufacturing: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muthu, S.S. Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing; Springer: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Innovationen für Nachhaltige Bekleidung. Available online: http://www.innabe.de/index.php?id=173 (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Hobson, K. ‘Weak’ or ‘trong’ sustainable consumption? Efficiency, degrowth, and the 10 Year Framework of Programmes. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 1082–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Fuchs, D. Strong sustainable consumption governance—Precondition for a degrowth path? J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 38, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Institutional change for strong sustainable consumption: Sustainable consumption and the degrowth economy. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2014, 10, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwozdz, W.; Nielsen, K.S.; Müller, T. An environmental perspective on clothing consumption: Consumer segments and their behavioral patterns. Sustainability 2017, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhückelkotten, S.; Moser, S.; Neitzke, H.P. Repräsentative Erhebung von Pro-Kopf-Verbräuchen Natürlicher Ressourcen in Deutschland (nach Bevölkerungsgruppen); Unweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2016.

- Wahnbaeck, C.; Brodde, K.; Growth, H. Usage & Attitude Mode/Fast Fashion, Ergebnisbericht; Greenpeace: Hamburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel-Verlag. Outfit 9.0: Kleidung und Armbanduhren; Spiegel-Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fashion Revolution. Consumer Survey Report. A Baseline on EU Consumer Attitudes to Sustainability and Supply Chain Transparency in the Fashion Industry; Fashion Revolution Foundation: Derbyshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S. Mapping Clothing Impacts in Europe: The Environmental Costs; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhückelkotten, S. Konsumverhalten im Spannungsfeld konkurrierender Interessen und Ansprüche: Lebensstile als Moderatoren des Konsums. In Die Verantwortung des Konsumenten; Heidbrink, L., Schmidt, I., Ahaus, B., Eds.; Campus: Frankfurt, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wiswede, G. Konsumsoziologie—Eine vergessene Disziplin. In Konsum. Soziologische, Ökonomische und Psychologische Perspektiven; Rosenkranz, D., Schneider, N.F., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2000; pp. 23–72. [Google Scholar]

- Forscht, T.; Swoboda, B. Käuferverhalten. Grundlagen—Perspektiven—Anwendungen, 4th ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T.; Møller Jensen, J. Shopping orientation and online clothing purchases: The role of gender and purchase situation. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 1154–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.; Wong, C. The consumption side of sustainable fashion supply chain. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Parasuraman, A.; Grewal, D.; Voss, G.B. The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, O.; Oumlil, A.B.; Tuncalp, S. Consumer values and the importance of store attributes. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1999, 27, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, K.; Petersen, L.; Hörisch, J.; Battenfeld, D. Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Keller, J. Shopping for clothes and sensitivity for the suffering of others: The role of compassion and values in sustainable fashion consumption. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 1119–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Geiger, S.M. To wear or to own? Influences of values on the attitudes toward and the engagement in collaborative fashion consumption. In Eco Friendly and Fair: Fast Fashion and Consumer Behavior; Heuer, M., Becker-Leifhold, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Joanes, T. Personal norms in a globalized world: Norm-activation processes and reduced clothing consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmeier, J.; Lwin, M.; Andersch, H.; Phau, I.; Seemann, A.K. Anticipated consumer guilt: An investigation into its antecedents and consequences for fair-trade consumption. J. Macromark. 2017, 37, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Joyner Armstrong, C.M. Collaborative consumption: The influence of fashion leadership, need for uniqueness, and materialism on female consumers’ adoption of clothing renting and swapping. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Household Consumption Expenditure on Clothing and Footwear in the European Union in 2017, by Country (in Million Euros). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/422020/clothing-footwear-consumption-expenditure-europe-eu/ (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Neugebauer, C.; Schewe, G. Wirtschaftsmacht Modeindustrie—Alles bleibt anders. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 2015, 65, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S. Der Zauber der Markenwelten, oder: “Sage mir, was du trägst und ich sage dir, wer du bist”. In Mode. Die Verzauberung des Körpers. Über die Verbindung von Mode und Religion; Sellmann, M., Ed.; Kühlen: Mönchengladbach, Germany, 2002; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Die Feinen Unterschiede. Kritik der Gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft; Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ebner, C.C. Kleidung Verändert: Mode im Kreislauf der Kultur; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugele, E.; Reiss, K. (Eds.) Jugend, Mode, Geschlecht. Die Inszenierung des Körpers in der Konsumkultur; Campus: Frankfurt, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert, G.; Kühl, A.; Weise, K. (Eds.) Modetheorie. Klassische Texte aus vier Jahrhunderten; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schiermer, B. Mode, Bewusstsein und Kommunikation. Soz. Syst. 2010, 16, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnierer, T. Modewandel und Gesellschaft. Die Dynamik von ‘in’ und ‘out’; Leske und Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Umweltbundesamt. Grüne Produkte in Deutschland 2017. Marktbeobachtungen für die Umweltpolitik; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2017; p. 39.

- Textile Exchange. Preferred Fibers and Materials. Market Report 2018; Textile Exchange: Austin, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Others. The State of Fashion 2017. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/The%20state%20of%20fashion/The-state-of-fashion-2017-McK-BoF-report.ashx (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Lehmann, M.; Arici, G.; Boger, S.; Martinez-Pardo, C.; Krueger, F.; Schneider, M.; Carrière-Pradal, B.; Schou, D. Pulse of the Fashion Industry. 2019 Update; Global Fashion Agenda: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sandes, F.S.; Leandro, J.C. Exploring the motivations and barriers for second hand product consumption. In Proceedings of the CLAV 2016 9th Latin American Retail Conference, Sao Paulo, Brasil, 20–21 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, F.; Roby, H.; Dibb, S. Sustainable clothing: Challenges, barriers and interventions for encouraging more sustainable consumer behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Percent |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 51.4 |

| Male | 48.6 |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 17.0 |

| 30–49 | 32.0 |

| 50–65 | 28.3 |

| ≥65 | 22.7 |

| Household net income (€) (without ‘do not know’ and ‘not specified’) | |

| <1.000 | 11.9 |

| 1.000–1.999 | 29.5 |

| 2.000–2.999 | 27.4 |

| 3.000–3.999 | 17.2 |

| 4.000–4.999 | 5.3 |

| ≥5.000 | 4.8 |

| Continued | |

| Educational attainment (German educational system) (without ‘do not know’ and ‘not specified’) | |

| General education school leaving certificate after grade 9 (Volks-/Hauptschulabschluss, Polytechnische Oberschule) | 37.8 |

| General education school leaving certificate after grade 10 (Mittlere Reife/Realschulabschluss, Polytechnische Oberschule) | 2.6 |

| Higher education entrance qualification (Abitur, Fachabitur) | 14.7 |

| University or university of applied sciences diploma | 15.8 |

| Other | 2.1 |

| Quantitative Level of Clothing Consumption | Wearing Time of Clothes | Purchase of More Sustainably Produced Clothing | Purchase of Second-Hand Clothing | Restriction of Clothing Consumption | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | all | f | m | all | f | m | all | f | m | all | f | m | all | f | m |

| Sociodemographic attributes | |||||||||||||||

| Age | −0.08 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.06 * | 0.05 * | 0.06 * | 0.04 | 0.08 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.04 | −0.17 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.22 *** | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Income | 0.21 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.23 *** | −0.08 *** | −0.07 * | −0.09 ** | 0.08 *** | 0.07 * | 0.10 ** | −0.08 *** | −0.02 | −0.10 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.23 *** |

| Attitudes | |||||||||||||||

| Consumption orientation | 0.40 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.38 *** | −0.40 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.44 *** | 0.07 ** | 0.03 | 0.08 * | 0.15 *** | 0.08 * | 0.17 *** | −0.37 *** | −0.35 *** | −0.35 *** |

| Fashion orientation | 0.43 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.38 *** | −0.33 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.35 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.07 * | 0.09 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.00 | 0.09 ** | −0.48 *** | −0.47 *** | −0.48 *** |

| Distinction | 0.27 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.27 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.25 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.03 | 0.12 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.04 | 0.18 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.26 *** |

| Creativity | 0.41 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.38 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.36 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.04 | 0.11 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.07 * | 0.18 *** | −0.34 *** | −0.32 *** | −0.32 *** |

| Individuality | 0.24 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.21 *** | −0.09 *** | −0.07 * | −0.12 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.07 *** | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| Price consciousness | −0.09 *** | −0.07 * | −0.15 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.14 *** | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.07 ** | 0.11 *** | 0.00 | 0.27 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.36 *** |

| Quality orientation | 0.17 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.20 *** | −0.10 *** | −0.08 ** | −0.11 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.26 *** | −0.06 ** | −0.06 * | −0.08 ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Habit | −0.15 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.10 ** | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.42 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.41 *** |

| Problem awareness | 0.08 *** | 0.04 | 0.09 ** | 0.04 | 0.11 *** | −0.02 | 0.31 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.31 *** | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.07 * | −0.06 ** | −0.06 | −0,02 |

| Sustainability awareness | 0.10 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.03 | 0.06 ** | 0.09 ** | 0,03 | 0.38 *** | 0.37 *** | 0,37 *** | 0.01 | 0,04 | −0.07 * | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0,02 |

| Social norms | |||||||||||||||

| Wearing time | ./. | ./. | ./. | 0.07 ** | 0.08** | 0.06* | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. |

| Sustainably prod. clothes | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | 0.31 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.34 *** | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. |

| Second-hand clothes | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | ./. | 0.46 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.44 *** | ./. | ./. | ./. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kleinhückelkotten, S.; Neitzke, H.-P. Social Acceptability of More Sustainable Alternatives in Clothing Consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226194

Kleinhückelkotten S, Neitzke H-P. Social Acceptability of More Sustainable Alternatives in Clothing Consumption. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226194

Chicago/Turabian StyleKleinhückelkotten, Silke, and H.-Peter Neitzke. 2019. "Social Acceptability of More Sustainable Alternatives in Clothing Consumption" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226194

APA StyleKleinhückelkotten, S., & Neitzke, H.-P. (2019). Social Acceptability of More Sustainable Alternatives in Clothing Consumption. Sustainability, 11(22), 6194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226194