1. Introduction

Scientists have often conceived of innovation as being controlled and moved onward by ethics. Therefore, any novelty is posed as a source of potential damage or risk in business [

1,

2] and in tourism [

3,

4,

5], but not as the consequence of ethics. Nevertheless, innovation should be an essential outcome of ethics, given that innovation is not inherently good [

6]. For this reason, it is not of value if it lacks responsibility. In addition, one might consider that when service companies innovate, the innovation consists of aspects, which are easier to evaluate on the basis of morality, such as organisational and marketing issues, rather than features such as technology, product, and the engineering process [

7]. However, we still don’t know too much about it, since how ethical management influences innovation and organises knowledge represents a gap in the research [

8].

To be precise, in the field of tourism, it is stated that innovation must drive corporate social responsibility [

9], as opposed to considering ethics as a determining factor. Even until a couple of decades ago, there were only a few studies focused on the role of ethics [

10]. Nevertheless, quite recently, environmental and social responsibility have become relatively shared in society. As a result, not only has quality entailed an ethical imperative grounded on growing market demand, but also managers have taken a moral responsibility with implications in terms of innovation. In fact, not only we should talk about the ethical consequence of management but also give credit to the ethical motive and optimism inspiring decision making in the hospitality context [

11,

12].

Nevertheless, there are still a limited number of tourism management studies linked to corporate social responsibility, especially research works to further understand how to engage employees and bring about competitive success [

13,

14,

15] and innovation [

8]. The need for this new direction is crucial for the sake of the social environment and the survival of the tourism industry itself [

16]. In actual fact, innovation is a critical aim for the company’s success and survival [

17], and society demands more innovation-based upon social ethics [

18].

On this basis, the objective of the current work is multi-fold. Firstly, it consists of analysing the causal role played by social responsibility in knowledge exchange between hotel employees. Secondly, it aims to examine how social responsibility influences the degree and type of innovation. Thirdly, it endeavours to study how innovation is brought about through that internal collaboration between hotel employees. Finally, environmental management is studied in order to measure its effect on knowledge exchange and innovation.

With these aims in mind, the research paper is divided into four parts: the review of literature where the five hypotheses are placed, the methodology to provide detailed information related to the survey and the measuring instruments, the analysis of the obtained empirical results, and the conclusion.

2. Review of the Literature

In spite of business ethics, trust research and care shouldn’t be interchanged and reduced to the same concept [

19]; these different approaches are linked to each other and show some similarities. In fact, all of them lead to the conclusion that social responsibility works as a key antecedent of knowledge exchange. For instance, within the field of business ethics, there is the utilitarian framework whose appraisal highlights the importance of obtaining more benefit than the cost from any human resource policy. Thus, it is relevant to analyse the risk associated with any decision so that advantages and disadvantages can be pondered in order to see how acceptable risk can be for the company and society as a whole [

20]. Similarly, within a business ethics approach, one might find that qualities such as honesty and other moral principles must favour a work climate committed to good employee communication [

21]. Hence, it seems logical to assume that knowledge exchange is also derived from these values [

22] and principles [

23]. In this context, the quality of the relationship between a leader and members of his group reduces the chance of turnover [

24] and, in turn, increase innovations [

25].

In addition, in the field of trust research, one might state that empowering guidance has been demonstrated as a precursor for the cohesive team where information is jointly held [

26]. Equally, trust is a consequence of fairness because of the correct distribution of benefits and costs favours trustworthiness and reliability [

27]. Likewise, leadership plays a crucial role in bringing about knowledge exchange by creating a trusting and committed atmosphere [

28]. For example, ethical and charismatic leadership relies on internal and societal interests, promotes individual thinking, and learns from criticism, and opens the way to independent forms of intercommunication [

29]. Similarly, knowledge exchange is induced by transformational leadership, given that this style of management highlights the importance of collaboration and a trusting work atmosphere [

30]. For these reasons, knowledge and innovation grow with trust [

31,

32], since the principle of fair exchange in knowledge networks is necessary [

33] and this kind of empowering leadership favours it [

26]. What’s more, ethical and transformational leadership is connected with employees’ creativity when mediating knowledge exchange [

34] and becomes a real servant leader when seeks empower their followers [

35].

Finally, and in reference to the ethics of care [

19], one might state that concern for the interests of others carries a sense of solidarity and duty whose benevolent interaction represents a share in itself with implications for innovation. Thus, Chung-Herrera et al. state not only that collaborating with others facilitates change, but also that being constructive in the face of setbacks and creating a comfortable working environment are desirable dimensions in the competency model for training new hospitality management students [

36]. Equally, Upchurch and Ruhland point out the work climate in lodging operations is rooted in an ethical organisational basis, so that certain criteria such as egoism and benevolence determine particular company circumstances [

37]. It looks to be so even within the Islamic work ethic, where the enjoyment of helping others is a key antecedent of knowledge exchange by means of a faithful atmosphere directed towards innovation capability [

38].

Therefore, as ethical leadership induces collective motivation [

39], and taking into consideration that the ethical tradition in business related to utility, honesty, duties and justice, as well as trust and care, brings about knowledge exchange between hotel employees, Hypothesis 1 is put forward as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Ethical management causes knowledge exchange in hospitality.

No doubt, ecological awareness is a kind of ethics and hence implies the same consequences for collaborative knowledge associated with business ethics, trust, and care. In fact, from the perspective of business ethics, ecological awareness is a useful resource to facilitate community cohesion and a more environmentally friendly form of management. In addition, cultural values and moral principles such as respect, sharing and reciprocity are included in ecological knowledge [

40]. From the perspective of trust research, ecological management puts forward some commandments, such as building trust, reducing uncertainty, tightening feedback loops, maintaining diversity, and fair reciprocity of treatment [

41]. Finally, care and solidarity might be considered within ecological management and are central to achieving fair and equitable exchanges with others [

42].

In addition, ecological ethics is a kind of social responsibility and this involves a particular constellation of consubstantial values and beliefs. To be specific, the environmentally friendly conscience entails a certain integrative capacity, organic leadership and horizontal organisational structures whose effects favour internal dialogue [

34] and are consistent with knowledge exchange. In fact, sometimes employees are the initiators of the environmental measures taken by their companies and are quite willing to undertake green actions [

43]. In summary, sustainable culture and values, and corporate social responsibility are firm factors determining a flexible organisational structure that enhances innovation stemming from employee participation and customer co-creation processes [

44].

Furthermore, it seems logical to think that knowledge exchange is more sustainable than circumstances without any opportunity to make good use of scale and scope economies. In fact, the more highly qualified employees are willing to exchange their knowledge, the greater is the output in terms of efficiencies and skill synergies [

45].

For these reasons, ecological management encourages employees to feel more ready to collaborate with each other and, consequently, more actively exchange their knowledge and share their skills so that Hypothesis 2 is grounded and states as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Ecological management causes knowledge exchange in hospitality.

Every novelty not only needs to adhere to norms and values in a given society, but also consumer acceptability, which is the measure of how diffused and successful the company’s production is. In fact, there are three types of innovation: product, process, and market [

46], the latter of which means that consumers and competitors affect the rate at which novelties are created by the company. For this reason, an ethical manager should be able to model their innovations by conceiving new ideas related to the demands of their clients and society, since markets demand more innovation-based upon social ethics [

18].

For instance, innovation is quite frequently an answer to social concerns and thus novelty is directed towards solving society’s problems. In this sense, it has been demonstrated, in the public sector, that ethical concerns are not barriers to innovation, but drivers that lead to changes and advances [

19]. Similarly, entrepreneurship might not be ethically questioned, despite breaking rules, if it carries economic growth, new opportunities for others, and a utilitarian moral improvement within the competitive systems of values existing in society [

1].

In addition, innovation needs ethical approaches, otherwise, novelties might go against the common good; so ethics involves a logical and long-term business survival necessity. Hence, prudence is a key value for facing novelties whereby balance freedom and control for managers act in the context of changes. In other words, there is no contradiction between prudence and innovation due to novelties requiring a certain level of stability and continuity to be maintained [

47].

Finally, quality is not only a market demand and self-protective condition of society but also an intrinsic ethical imperative of leaders [

48]. In this sense, managers take on a moral responsibility deriving from their professionalism, since not only is social responsibility the way companies are competing successfully nowadays, but also innovation is how managers do their best. In fact, ethics favour to go beyond assumptions and limits [

49] and ethical leadership impacts creativity by a psychological empowerment [

32,

50], so an ethical approach favours an enduring commitment to competitiveness and innovation by showing an eager enthusiasm for improvement and excellence. For instance, ethical leadership enhances innovation by intrinsically motivating a group, as well as individuals, to respond to changes and improvements [

51,

52]. In fact, it is evident that to innovate with an ethical foundation increases efficacy [

48] and employees’ creativity [

53]. For these reasons, innovation is directly proportional to the degree of social responsibility, people-orientation and the morality of managers [

48].

Hence, as ethics bring about legitimacy, survivability, and competitiveness, Hypothesis 3 is fully grounded and put forward as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Ethical management causes innovation in hospitality.

Similarly, since concern for the environment is on hotel guests’ minds, ecological improvements should be considered in the context of service quality [

54] so innovations that consist of designing new green-friendly products meet market opportunities [

55]. Hence, environmental responsibility is also a key differential of competitive advantage [

56] due to the fact that ‘green features’ are not only broadly accepted in society nowadays, and thus in demand by the main markets, but are also an indispensable part of high-quality products. In this instance, service quality and the ‘green offer’ might be assimilated to some extent, since clients’ expectations cannot be met without considering their quality of life. Not in vain, sustainability and innovation find social legitimacy by emphasizing and improving the importance of quality [

57].

What’s more, innovation is useful for working out environmental problems [

3,

58], and so finds legitimacy. For example, the principle of sustainability and innovation together comprises the reduction of unnecessary risks whereby the acquiescence and support of local communities are obtained [

59]. Similarly, entrepreneurial pragmatism finds legitimacy by building a bridge between value creation and sustainability in order to achieve continuous improvement and reduce errors [

60].

Likewise, sustainability and innovation have in common their future orientation and thus, through the principle of prudence or precaution, are involved in the quest to achieve a good long-term performance. Firstly, prior to innovation, it is essential to demand a preventative and precautionary principle, given that there is always a risk associated with any advance. Secondly, the benefit related to innovation might be limited to the benefit of the few, but unacceptable for society as a whole. In other words, it is important to reflect on how a novelty impacts society because the innovation option implies an ethical choice. In summary, innovation assimilates environmental ethics as far as long-term survivability and society as a whole are essential to the meaning of any advance [

61].

In addition, environmental ethics is a legal requirement that managers have to strictly follow; otherwise, companies might be fined. For this reason, the vast majority of the tourism industry’s environmental innovations are implemented as defensive or self-protective strategies. In other words, external forces stemming from the market are the incentives and the benchmark factor for adopting environmental advances by hotel companies. On the other side, the role played by endogenous development is less influential than the more active pressures of consumers, authorities, suppliers, and competitors [

3].

Furthermore, ecological approaches generate competitive advantages by means of efficiency and cost-reduction efforts. Eco-efficiency produces cost improvements by making much better use of resources and reducing environmental damages [

62]. Similarly, corporate environmental ethics can generate green process innovations by being more productive (reusing & recycling) and efficient (reducing), with the aim of saving and decreasing costs [

55]. In fact, environmental ethics contribute to hotel value by means of innovating for the sake of cost-efficiency advantages [

63]. Even pro-environmental measures implemented by companies are very well funded externally and require low investment [

64].

Therefore, since ecological management pursues enduring competitive advantages related to cost, as well as differentiation, that meet society’s standards and seek legitimacy—moreover, is a self-protective and legal survival factor that nobody can overlook—Hypothesis 4 might be grounded and states as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Ecological management causes innovation in hospitality.

Nobody knows everything, but the more one knows, the more one is able to identify what is ignored or not known. For this reason, knowledge is a critical factor for innovation, given that the former fosters the incidence and systematisation of the latter. In other words, knowledge needs recognition to give rise to innovation, in so far as knowledge being tacit represents a barrier to innovation being produced and shared [

65]. In this respect, employees’ skills are essential for galvanising knowledge towards innovation [

3].

What’s more, knowledge is a source of inspiration for innovation. Mainly, because knowledge motivates one to gather new knowledge configurations and this is an innovation in itself. To be precise, learning capability is a direct consequence of employees’ knowledge, since this causes more flexibility in taking up novelties [

66], gaining sensitivity towards gathering a broad variety of further knowledge [

67], and fostering a greater ability to change and innovate [

68]. It is no coincidence that knowledge management influences innovation [

69].

In addition, if one collaborates with others, the usable knowledge is greater thanks to the adding and sharing process, and in this way research gaps, unnoticed learning opportunities, and disregarded approaches might be brought into focus by innovation initiatives. In fact, the level of integration influences success in innovation, given that innovation is always multidisciplinary [

70]. Consequently, innovation is more likely to be successful when managers can count on a large number of knowledge sources [

71,

72] and firms are more open to gathering not only different but also new ideas [

73]. In this sense, market orientation and inter-functional teamwork determine firm innovation related to service performance and product [

74,

75,

76,

77].

Furthermore, the knowledge exchange dynamic involves unavoidable dialectics stemming from the fact that it’s nearly impossible for everyone to hold the same opinion and agree on how to proceed. Hence, knowledge exchange compels the reaching of a new synthesis by contrasting different perspectives if advances consist of blended contributions. Sometimes, this process leads to creative destruction, which occurs, for example, when an internal entrepreneur, forced into action by fierce competition, disturbs the company’s equilibrium with new ideas [

3]. Accepting that as a matter of fact, cultures that emphasise the active participation of employees and the importance of learning tend to be more innovative [

78,

79]. In addition to this, a broad variety of networks is a determining factor for bringing about innovations in tourism firms [

80]. In fact, the more qualified hotel employees are and the more exchange of knowledge there is between them, the more management innovations are put into practice [

81].

Likewise, knowledge management capability determines a more efficient use of resources [

82]. Knowledge sharing is more convenient and efficient because it logically socialises the benefits of information and general awareness and reduces acceptation of risk rooted in any new idea. For instance, cross-functional integration between research, development, and marketing favours efficiency, whose success is in function of the degree of innovativeness [

83].

In summary, knowledge exchange leads to recognition and inspiration, and makes much better use of fragmented information, overcoming the opposition of others for the sake of innovation. Thus, among the causes of innovation success in hospitality, the literature has highlighted the importance of employee commitment with internal collaboration [

25] and knowledge sharing [

84], and it is known how relevant ethics can be for engaging human resources [

48,

85]. On this basis, Hypothesis 5 is put forward as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Knowledge exchange causes innovation in hospitality.

6. Conclusions

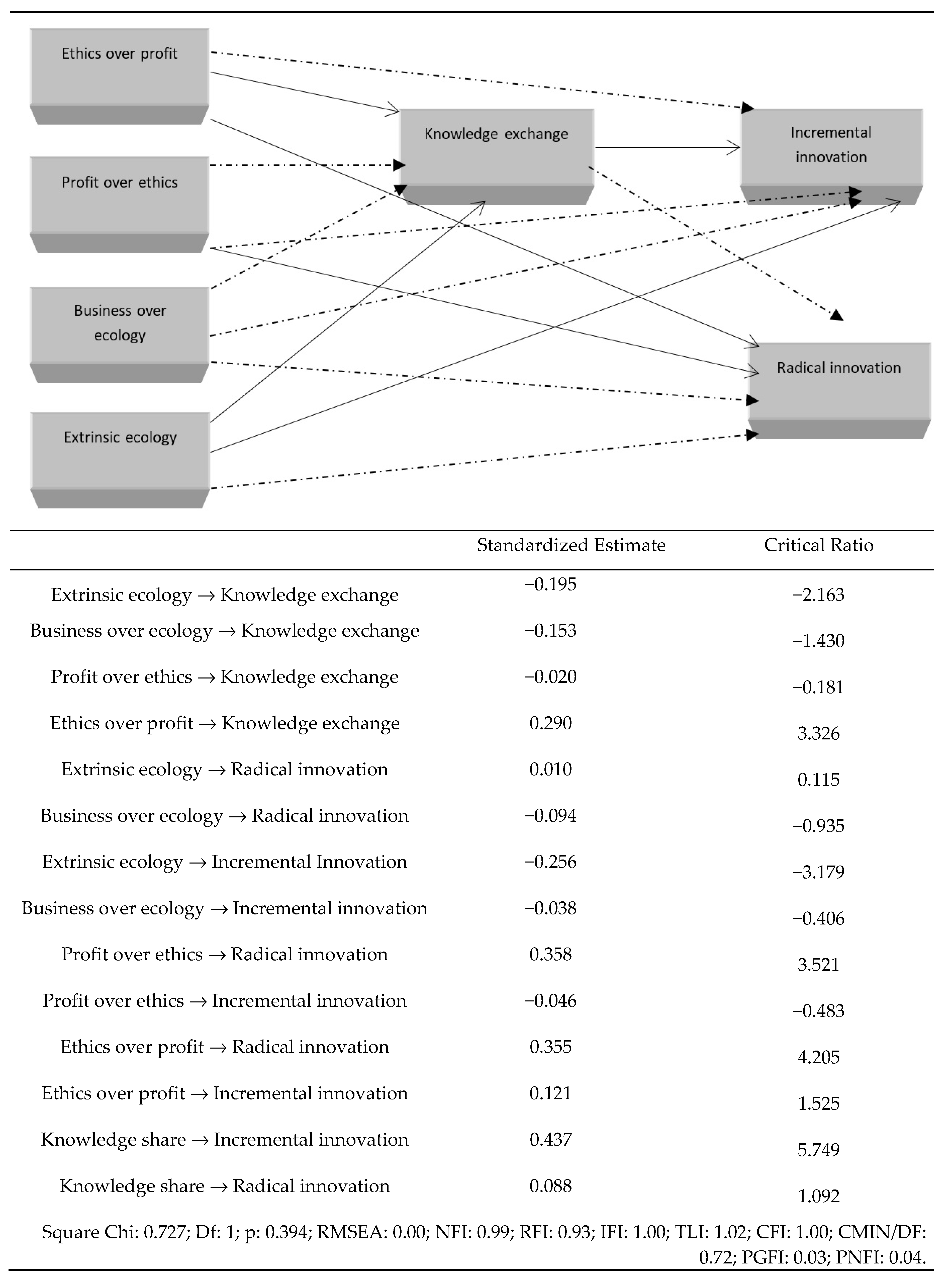

Firstly, this paper proofs the antecedent role played by social responsibility to generate innovation in hotels. Secondly, it demonstrates the direct role of employee knowledge exchange to produce breakthrough. Thirdly, it evidences the importance of ethics to trigger knowledge exchange driven by novelties. Finally, it casts doubts on how effective extrinsic ethical drives, such as extrinsic ecology, can be for causing innovations. From a practical implication perspective, one might suggest that if the hotel’s priority is designing new products and services disruptively, the tourism firm should find intrinsic and ethical directors. But if the primacy is innovating progressively without radical changes, novelties are expected to come out from team knowledge exchange and from extrinsically ethical commitments, such as the mere intention to meet the legal requirement. For instance, whereas tools for cultivating ethical standards such as personal growth courses seem to be highly recommended for managers in order to promote radical novelties, team-building techniques might be more suitable for ensuring continually improving managerial processes in hotels. In any case, it is clear that incremental and radical inspirations show different origins and thus collective and extrinsic measures must be taken for the former, although individual and intrinsic actions must be taken for the latter.

In addition, one might state that, obviously, if profit is emphasized over ethics by hotel managers, this course of action might carry with it radical innovations. Nevertheless, despite being true, this obtained evidence is not relevant, since it was always known that not all possible invention is necessarily good, and hence ethical questions must be posed for any scientific performance. In fact, entrepreneurship implies breaking rules through a destructive creative process to take advantage of business opportunities [

1]. What might be more interesting is the fact that subjecting ethics to profitability leads to a lesser degree of innovation than highlighting the primacy of social responsibility. In this sense, it might be pointed out that ethical management is not only a key factor in reducing the uncontrollable and undesirable output of new products and services, but also the most effective way to generate radical innovations for the hotel. The rationale for this evidence might derive from the difference between transactional and transformational leadership, as far as there is a link between incremental and radical innovation and the former and latter management styles, respectively [

97,

98,

99].

On this basis, one might propose that, as the practical implication for hospitality education, social responsibility content plays a predominant role in order to train for innovation. So, as innovation is a key variable for competitive success in tourism, philosophy and ethics are as essential as other utilitarian subject matters, for instance, finance, human resources, production, and marketing. In fact, in the words of Lugosi [

100] ethics is becoming an increasingly important management skill and according to Yeung and Pine and Vallen and Casado an essential part of the hospitality curriculum [

101,

102]. Nevertheless, as the extrinsic ecological management does not work to trigger innovation, one might question the potential impact of codes of ethics to boost innovations in hospitality, apart from its utility as guiding professionalism and integrity [

103]. The same would apply to governmental regulations and any other external reinforcement.

Future lines of research can be put forward by raising some questions and considering the limitations related to the present paper. For instance, it has been demonstrated that the social responsibility capital of the hotel manager affects radical innovation linearly, but if managerial ethics is too high, does the level of knowledge exchange also go up continually? According to Molina-Morales and Martínez-Fernández, trust capital in the network doesn’t affect innovation linearly, since, after a threshold, if trust in the local relationship is too high, the level of innovation goes down [

104]. This has not been contrasted in the current research since ethical leadership has been defined in general and not in regard to the company’s human resources in particular.

Furthermore, it would be of interest to give insight into why radical innovations are only produced by individuals and not grouped sources, so that one might learn how to produce disruptive innovations by making good use of ethical teams. Is it because radical innovations are tacit knowledge-based, while incremental novelties are founded on explicit knowledge, as Rebernik and Sirek suggest? [

65]. In any case, Brooker and Joppe state that innovation should always be inclusive and not exclusive [

105].

In another vein, it might be suggested that future research brings into focus not why incremental and radical innovations are produced, but how they are generated. Indeed, despite the current paper attempting to explain it on theoretical grounds, such as business ethics, trust, and other mentioned framework, it is true that these doctrinal tenets have not been contrasted in the verified hypotheses. Therefore, it seems logical to recommend that future research contrast empirically the supposed antecedent role played by trust, honesty, rights and so on for resulting in hotel innovations.

Furthermore, it might be interesting to investigate the possible causal role played by managers’ intrinsically environmental motivations to enhance innovation, given that here only a kind of external ecological motivation has been used.

Perhaps, it is too obvious to state that there must be much to know about what might be considered a new line of research: ethics as a causative variable of tourism innovation. Afterwards, one might state that ethics is more than a prudent principle and mere sales and reputational technique at the disposal of managers, given that its innovative utility has also been henceforth demonstrated.

Finally, it is noteworthy that the current paper shows some limitations. Firstly, if it were not for the fact that the present paper encompasses five hypotheses, the paper would gain more insight into how to enhance knowledge exchange and innovation from ethics. For this reason, there is a significant room for improvement consisting of overcoming this exploratory approach. On this basis, it is advisable to perform a more profound analysis of the evidence related to how ethics can cause innovations in hospitality and other sectors. Secondly, as this research has not included any variable related to intrinsic ecological management, which had been more ethically related than any extrinsic drive, future lines of research are called for analysing how a real intrinsic ecological ethics might influences both knowledge exchange and innovation in hospitality and other sectors.