Flights Dominate Travel Emissions of Young Urbanites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The First Contradiction: Emissions from Long-Distance Travel Higher in Cities and City Centers

1.2. The Second Contradiction: Environmental Concern Unrelated or Positively Related to Flights and Emissions

1.3. Research Goals and Questions

- The structure of GHG emissions from travel in the Reykjavik Capital Region (Reykjavik) in Iceland

- a.

- The distribution of emissions among the studied population.

- b.

- The levels of emissions from local, domestic and international travel.

- c.

- The geographical distribution of emissions within an urban region based on residential location.

- Factors that influence this structure, specifically focusing on the contradictions described above:

- a.

- How does residential location within the urban region influence emissions from travel?

- b.

- How does awareness of climate change influence emissions from travel?

- c.

- What are other factors that influence the amount of travel-related emissions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Area

2.2. SoftGIS Survey

2.3. Allocation and Estimation of Trip Distances and GHG Emissions

2.4. Modality Styles

2.5. Geographical Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Structure of Travel Emissions

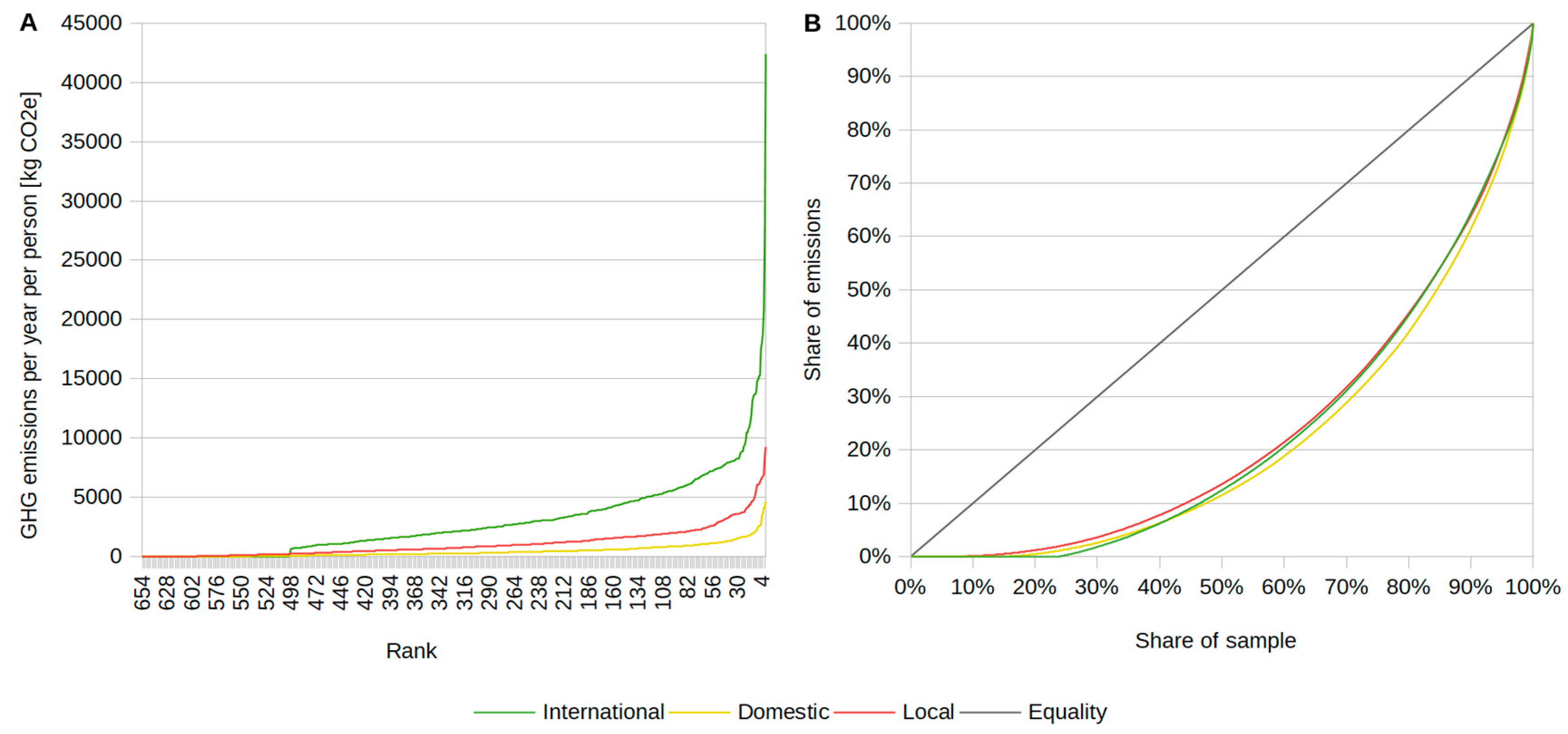

3.1.1. Unequal Distribution of Travel Emissions

3.1.2. Characteristics of More and Less Mobile Groups Distribution of Travel Emissions

3.1.3. The Internal Structure of Travel Emissions

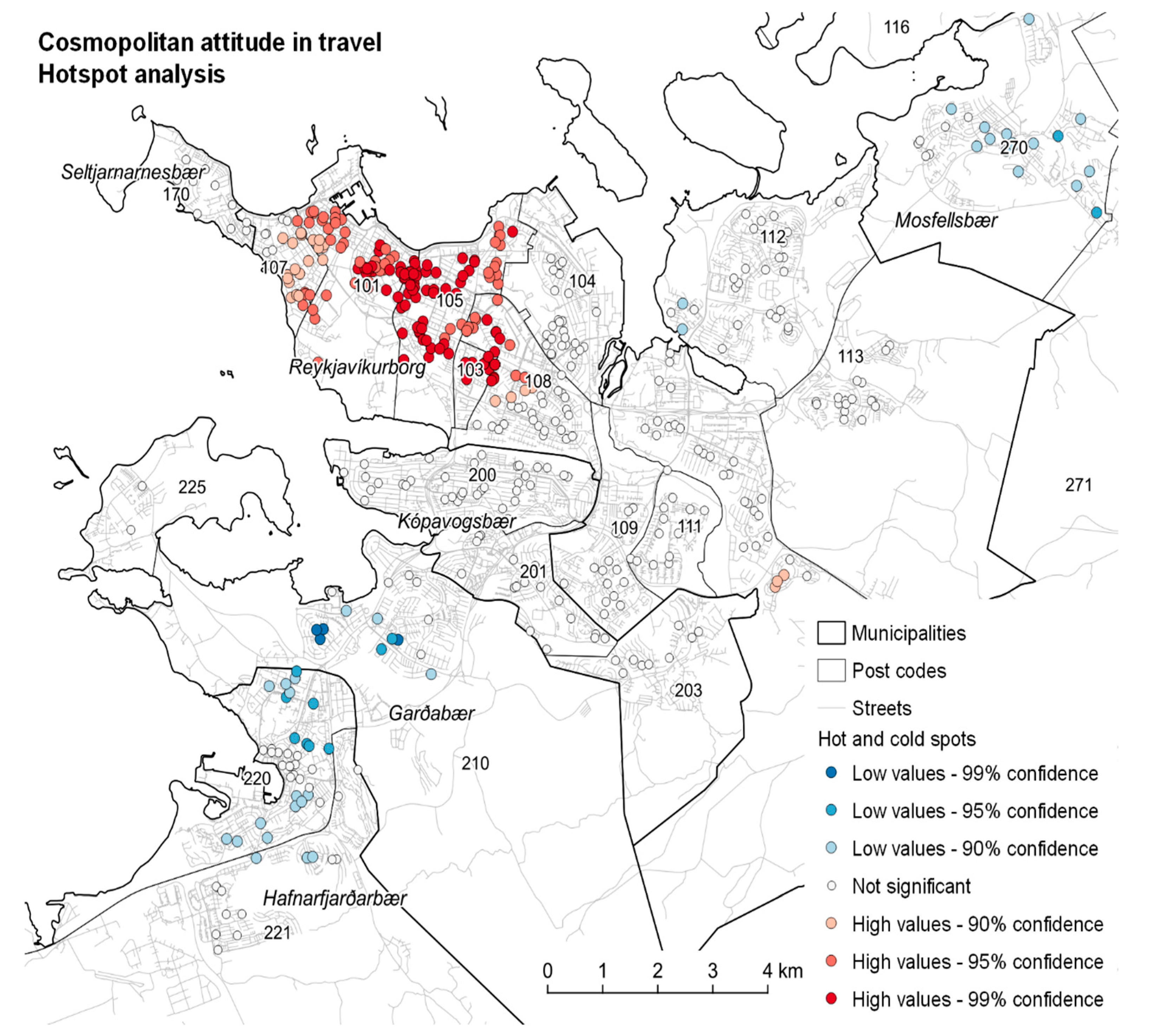

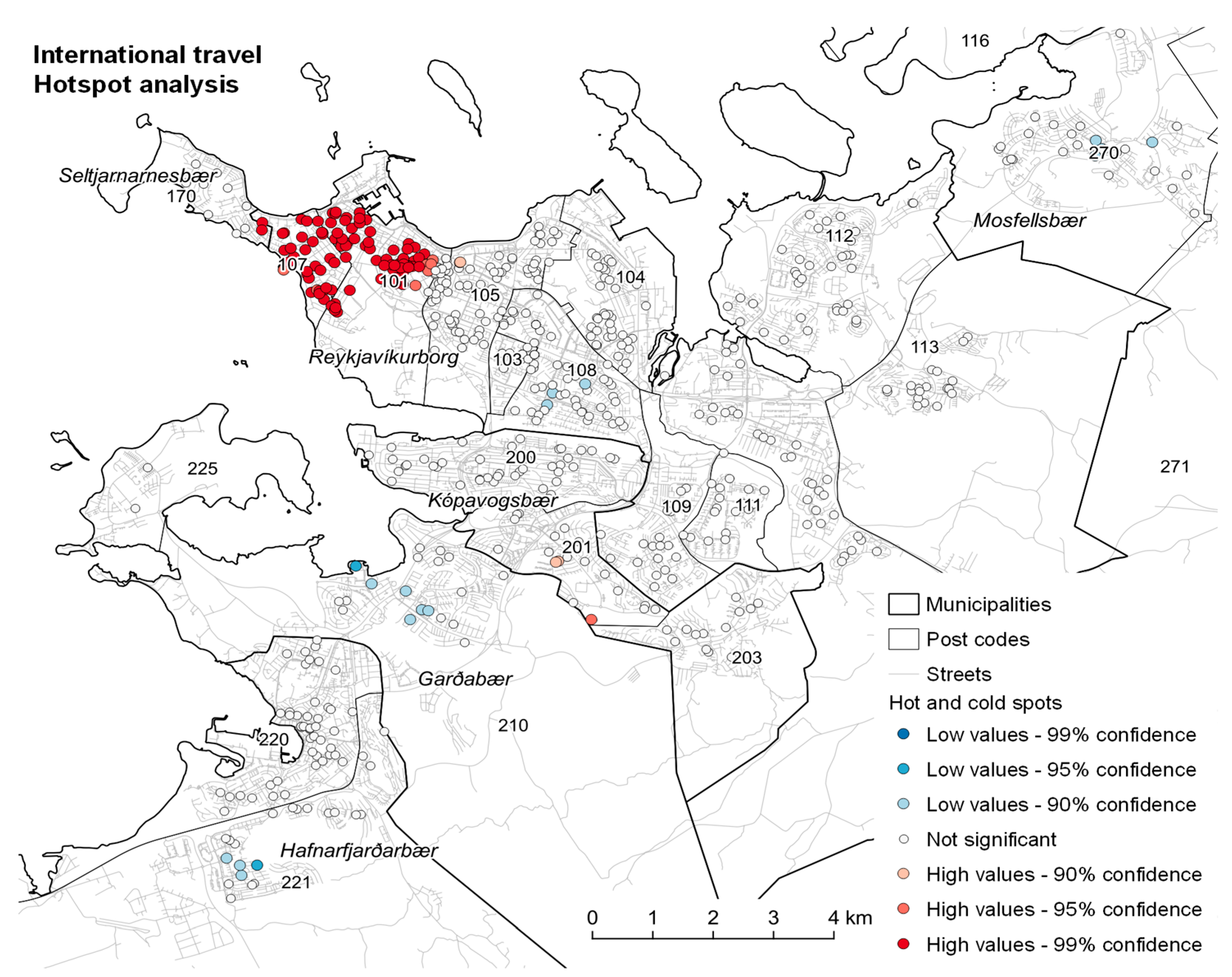

3.1.4. Geographical Distribution of Travel Emissions

3.1.5. Travel Emissions and Modality Styles

3.1.6. Travel-Related Emissions and Climate Change Awareness

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

International Travel Emissions

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Further Studies

4.3. Policy Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Methods

Appendix A.1. Trip Distances and Frequencies

Appendix A.2. Emissions Estimation with LCA

| Travel Scope | Travel Mode | Explanation and Sources | Direct Emissions: Combustion | Indirect Emissions | Total Emissions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel Production | Life-Cycle | |||||

| Local | Car | Reported fuel efficiency (liters per km, survey data) times 2.36 kg CO2e/liter [88], divided by 1.3 car occupancy [87]. Indirect emissions for San Francisco Muni [49]. | 0.138 (average) | 0.026 | 0.074 | 0.238 |

| Bus | Natural gas bus, the average occupancy rate in local traffic, 18/50 passengers [87]. | 0.069 | 0.031 | 0.050 | 0.150 | |

| Domestic and international | Plane <800 km | LLGHGs and SLCFs included [15], indirect emissions for a midsize aircraft [49]. | 0.300 | Included in combustion factor | 0.020 | 0.320 |

| Plane >800 km | 0.240 | Included in combustion factor | 0.020 | 0.260 | ||

| Ferry | Helsinki-Stockholm, average occupancy [87], indirect emissions for a midsize aircraft [49]. | 0.223 | 0.015 | 0.020 | 0.258 | |

| Bus | Diesel bus, average occupancy rate on long distance trips, 12/50 passengers [87]. | 0.049 | 0.037 | 0.058 | 0.144 | |

| Train | Pendolino and intercity trains, average occupancy [87]. Indirect emissions for an SFBA Caltrain [49]. | 0.022 | Included in combustion factor | 0.062 | 0.084 | |

Appendix A.3. Modality Styles

| Non-Commuting | Commuting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Car | Bus | Foot | Bicycle | Car | Bus | Foot | Bicycle | |

| Bus commuters | 60 | 10% | 82% | 4% | 5% | 37% | 22% | 36% | 5% |

| Consistent car commuters | 258 | 91% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 88% | 1% | 9% | 2% |

| Non-commuters | 101 | - | - | - | - | 63% | 4% | 28% | 5% |

| Multi-modal car commuters | 148 | 88% | 7% | 3% | 2% | 41% | 1% | 52% | 6% |

| Pedestrian commuters | 90 | 6% | 1% | 89% | 3% | 34% | 4% | 58% | 4% |

| Bicycle commuters | 60 | 11% | 4% | 6% | 78% | 34% | 2% | 30% | 34% |

| Sample | 717 | 62% | 11% | 16% | 10% | 60% | 4% | 30% | 6% |

Appendix A.4. Urban Form Measures

| Zone Name | Definition | GIS Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| The central pedestrian zone | Densely built and populated, located within a walkable distance from the main commercial center (up to 1500 m), contains a high number and diversity of jobs and services, and has good access to public transport. | Assigned to the cells within the contiguous area within 1500 m network distance from the main commercial center. |

| The fringe of the central pedestrian zone | Densely built and populated, located within a bikeable distance from the main commercial center (up to 3000 m) from the main commercial center, contains a high number and diversity of jobs and services, and has good access to public transport. | Assigned to the cells within the contiguous area between 1500 and 3000 m distance from the main commercial center. |

| Intensive public transportation zone | The area in which the public transport frequency is at least 10 departures per hour and walking distance to a bus stop is less than 5 min (332 m) | Assigned to the cells not included in the above zones and having a bus stop with at least 10 departures per hour within a 5 min walk (332 m street network distance). |

| Basic public transportation zone | The area in which the public transport frequency is at least 4 departures per hour and walking distance to a bus stop is less than 5 min (332 m) | Assigned to the cells not included in the above zones and having a bus stop with at least 4 departures per hour within a 5 min walk (332 m street network distance). |

| Car-oriented zone | The area in which the public transport frequency is less than 4 departures per hour or there is no bus stop within walking distance of 5 min (332 m) | Assigned to the remaining cells, not included in the above zones. |

Appendix A.5. Factor Analysis

| Item | Factor 1: Pro-Environmental Attitude | Factor 2: Climate Change Awareness | Factor 3: Cosmopolitan Attitude in Travel | Factor4: Preference for Urban vs. Natural Settings in Travel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I want to live as ecologically as possible | 0.572 | |||

| I am very concerned about environmental issues | 0.538 | 0.314 | ||

| I think about how I can reduce environmental damage when I go on holiday | 0.776 | |||

| I think about the environmental impact of services I use | 0.810 | |||

| When shopping, I rarely think about the environmental impact of the things I buy | -0.528 | |||

| I am willing to reduce my use of air travel because of the environment | 0.484 | |||

| Experiencing different cultures is very important for me | 0.687 | |||

| Experiencing different cultures and destinations is more important than saving natural resources | 0.355 | |||

| Exploring new places is an important part of my lifestyle | 0.826 | |||

| It is easy for me to jump to a plane and go on a trip | 0.383 | |||

| I feel at home wherever in the world I go | 0.332 | |||

| Sometimes it is necessary to take a break from urban life | 0.237 | −0.295 | ||

| I find it more interesting on a city street than out in the forest looking at trees and birds | 0.682 | |||

| I would rather spend my weekend in the city than in wilderness areas | 0.790 | |||

| There is evidence of global climate change | 0.754 | |||

| The main causes of global warming are human activities | 0.826 | |||

| Global warming will bring about some serious negative consequences | 0.858 |

| Item | Factor 1: Suburban Preference | Factor 2: Pro-Car Attitude | Factor 3: Preference for Shared Housing and Transport | Factor 4: Preference for Nature and Privacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I prefer to live in a suburban neighborhood, even if it means traveling longer distances | 0.883 | |||

| If I could live anywhere I would live in the suburbs | 0.827 | |||

| Suburban life is boring | −0.71 | |||

| I like living in a neighborhood where there is a lot going on | −0.509 | 0.336 | ||

| I don’t mind traveling a bit longer for the everyday services I use | 0.458 | |||

| I appreciate tranquility and calmness in a residential area | 0.387 | 0.253 | ||

| I want to live close to the vast nature and recreational areas | 0.319 | 0.457 | ||

| Having shops and services within walking distance of my home is important to me | −0.281 | |||

| The car is my preferred way of getting around the city | 0.903 | |||

| I appreciate good travel connections by car | 0.679 | |||

| I prefer getting around in an active way such as walking or cycling | −0.599 | 0.285 | ||

| I don’t mind getting around using public transportation | −0.548 | |||

| I can be comfortable living in close proximity to my neighbors | 0.834 | −0.285 | ||

| Living in a multiple-family unit would not give me enough privacy | −0.459 | 0.583 | ||

| I am comfortable riding with strangers | 0.331 | |||

| The neighborhood park is enough nature for me | 0.274 | |||

| I like to have a large yard at my home | 0.523 |

Appendix B. Results

| Local Travel | Domestic Travel | International Travel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Demographic Variables | Distance [km] | GHGs [kg CO2e] | Trip Count | Distance [km] | GHGs [kg CO2e] | Trip Count | Distance | GHGs [kg CO2e] |

| Sample | 5199 | 1079 | 9.04 | 2456 | 448 | 2.13 | 12208 | 2960 |

| Household type: Single | 4305 | 868 | 7.66 | 1990 | 386 | 2.32 | 12086 | 2833 |

| Household type: Couple | 5167 | 1081 | 9.34 | 3014 | 622 | 2.58 | 15251 | 3772 |

| Household type: Family | 5625 | 1172 | 9.54 | 2454 | 410 | 1.88 | 11143 | 2717 |

| Low education (basic, vocational, secondary) | 4972 | 1071 | 7.93 | 2188 | 432 | 2.01 | 11466 | 2693 |

| Medium education (undergraduate) | 5062 | 1036 | 8.92 | 2550 | 443 | 2.17 | 11679 | 2848 |

| High education (graduate and postgraduate) | 5542 | 1127 | 10.08 | 2560 | 462 | 2.21 | 13395 | 3302 |

| Low language skills (1–2) | 4991 | 1070 | 9.34 | 2590 | 480 | 1.79 | 10757 | 2573 |

| Medium language skills (3) | 5601 | 1121 | 8.63 | 2227 | 388 | 2.26 | 12506 | 3047 |

| High language skills (4+) | 4998 | 998 | 8.79 | 2518 | 479 | 3.32 | 18339 | 4572 |

| Gender: Female | 5192 | 1057 | 9.71 | 2541 | 450 | 2.20 | 12364 | 3001 |

| Gender: Male | 5229 | 1121 | 8.24 | 2383 | 454 | 2.04 | 11913 | 2882 |

| Hours worked low (less than 35) | 3794 | 771 | 9.22 | 2483 | 465 | 1.81 | 9725 | 2364 |

| Hours worked medium (35–45) | 5528 | 1128 | 8.94 | 2387 | 432 | 2.16 | 12621 | 3059 |

| Hours worked high (more than 45) | 5544 | 1205 | 9.18 | 2600 | 473 | 2.29 | 13155 | 3189 |

| Apartment: Yes | 5329 | 1097 | 9.65 | 2654 | 497 | 2.29 | 12800 | 3123 |

| Apartment: No | 5005 | 1052 | 8.01 | 2107 | 362 | 1.82 | 11073 | 2651 |

| Yard: Yes | 4936 | 1017 | 8.90 | 2347 | 420 | 1.95 | 11448 | 2776 |

| Yard: No | 5479 | 1143 | 9.24 | 2569 | 477 | 2.28 | 12880 | 3124 |

| Cabin: Yes | 5253 | 1098 | 10.88 | 2897 | 509 | 2.09 | 12348 | 3025 |

| Cabin: No | 5200 | 1072 | 7.62 | 2130 | 404 | 2.17 | 12234 | 2940 |

| The income per CU: Low (below 375k) | 4785 | 934 | 7.49 | 2102 | 373 | 1.67 | 10283 | 2490 |

| The income per CU: Medium (375–550k) | 5116 | 1088 | 9.54 | 2416 | 424 | 2.48 | 12733 | 3112 |

| The income per CU: High (above 550k) | 5771 | 1208 | 10.39 | 2907 | 549 | 2.34 | 13952 | 3394 |

| Basic public transportation zone | 5887 | 1258 | 10.57 | 2733 | 504 | 1.97 | 12078 | 2990 |

| Car-oriented zone | 6605 | 1431 | 8.81 | 2328 | 412 | 1.99 | 10855 | 2668 |

| Central pedestrian zone | 2872 | 502 | 8.67 | 2347 | 447 | 2.40 | 15165 | 3645 |

| The fringe of the central pedestrian zone | 4273 | 824 | 8.98 | 2697 | 497 | 2.27 | 13536 | 3172 |

| Intensive public transportation zone | 3991 | 866 | 7.93 | 2441 | 457 | 2.20 | 9915 | 2574 |

| Pedestrian zones of sub-centers | 5280 | 1102 | 8.18 | 1894 | 324 | 2.04 | 10077 | 2453 |

| Fixed Distance Band | Local (log) n = 621 | Domestic (log) n = 564 | International (log) n = 499 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 m | 0.128 (p = 0) | 0.001 (p = 0.857) | 0.004 (p = 0.744) |

| 1000 m | 0.134 (p = 0) | −0.004 (p = 0.832) | 0.009 (p = 0.308) |

| 1500 m | 0.146 (p = 0) | −0.001 (p = 0.898) | −0.015 (p = 0.096) |

| 2000 m | 0.134 (p = 0) | 0.005 (p = 0.234) | 0.006 (p = 0.178) |

| 2500 m | 0.002 (p = 0.425) |

| Travel-Related GHG Emissions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel-Related Urban Zone | Modality Style | N | Local | Domestic | International |

| Basic public transportation zone | Bus commuters | 8 | 968 | 594 | 4382 |

| Consistent car-commuters | 59 | 1650 | 653 | 3213 | |

| Non-commuters | 10 | 501 | 215 | 2160 | |

| Multi-modal car commuters | 15 | 1888 | 357 | 2283 | |

| Pedestrian commuters | 7 | 482 | 387 | 3826 | |

| Bicycle commuters | 7 | 364 | 214 | 2542 | |

| Car-oriented zone | Bus commuters | 14 | 1512 | 229 | 843 |

| Consistent car-commuters | 97 | 1973 | 490 | 3591 | |

| Non-commuters | 23 | 789 | 342 | 1967 | |

| Multi-modal car commuters | 47 | 1550 | 395 | 2149 | |

| Pedestrian commuters | 19 | 463 | 406 | 1878 | |

| Bicycle commuters | 15 | 483 | 267 | 2165 | |

| Central pedestrian zone | Bus commuters | 10 | 377 | 455 | 3717 |

| Consistent car-commuters | 17 | 1071 | 578 | 4693 | |

| Non-commuters | 8 | 89 | 255 | 3018 | |

| Multi-modal car commuters | 18 | 1108 | 671 | 3775 | |

| Pedestrian commuters | 29 | 129 | 290 | 3028 | |

| Bicycle commuters | 11 | 153 | 497 | 4491 | |

| The fringe of the central pedestrian zone | Bus commuters | 16 | 547 | 468 | 3317 |

| Consistent car-commuters | 43 | 1476 | 582 | 3723 | |

| Non-commuters | 16 | 396 | 504 | 2517 | |

| Multi-modal car commuters | 32 | 1246 | 447 | 2783 | |

| Pedestrian commuters | 24 | 191 | 388 | 3365 | |

| Bicycle commuters | 19 | 218 | 625 | 3220 | |

| Intensive public transportation zone | Bus commuters | 6 | 860 | 198 | 2357 |

| Consistent car-commuters | 25 | 1353 | 293 | 2434 | |

| Non-commuters | 17 | 475 | 331 | 2042 | |

| Multi-modal car commuters | 24 | 1353 | 485 | 3249 | |

| Pedestrian commuters | 4 | 186 | 854 | 1109 | |

| Bicycle commuters | 5 | 490 | 203 | 2044 | |

| Sample | 645 | 1119 | 454 | 2996 | |

| There is Evidence of Global Climate Change | The main Causes of Global Warming are Human Activities | Global Warming Will Bring about Some Serious Negative Consequences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree or Unsure | Agree | Strongly Agree | Disagree or Unsure | Agree | Strongly Agree | Disagree or Unsure | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

| Languages spoken | One | 11% | 5% | 3% | 10% | 4% | 2% | 10% | 5% | 3% |

| Two | 49% | 49% | 51% | 48% | 51% | 50% | 50% | 52% | 49% | |

| Three | 31% | 36% | 35% | 32% | 34% | 36% | 32% | 36% | 35% | |

| Four or more | 9% | 10% | 11% | 10% | 10% | 12% | 9% | 8% | 13% | |

| Education level | Basic or secondary | 28% | 26% | 20% | 31% | 24% | 20% | 30% | 20% | 23% |

| Lower tertiary | 46% | 44% | 37% | 43% | 38% | 40% | 44% | 44% | 37% | |

| Graduate or postgraduate | 27% | 30% | 42% | 26% | 39% | 40% | 26% | 37% | 40% | |

| Income per CU | Low—below 375 k | 33% | 36% | 33% | 39% | 30% | 34% | 34% | 35% | 33% |

| Medium—between 375 and 550 k | 29% | 33% | 34% | 28% | 37% | 32% | 34% | 32% | 34% | |

| High—above 550 k | 37% | 31% | 33% | 34% | 33% | 33% | 33% | 33% | 34% | |

References

- IPCC. Global Warming 1.5 °C: An IPCC Special Report Impacts Global Warming 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, Context Strengthening Global Response to Threat Climate Change, Sustainable Development, Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Rogelj, J.; Shindell, D.; Jiang, K.; Fifita, S.; Forster, P.; Ginzburg, V.; Handa, C.; Kheshgi, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Kriegler, E.; et al. 2018: Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5 °C in the Context of Sustainable Development. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C; An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, H.D.; Zickfeld, K.; Knutti, R.; Allen, M.R. Focus on cumulative emissions, global carbon budgets and the implications for climate mitigation targets. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 13, 010201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, J.; Schaeffer, M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gillett, N.P.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Riahi, K.; Allen, M.; Knutti, R. Differences between carbon budget estimates unravelled. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Comi, A. Urban Freight Transport Planning towards Green Goals: Synthetic Environmental Evidence from Tested Results. Sustainability 2016, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the Built Environment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P. Urban form and travel behavior: Experience from a Nordic context. J. Transp. Land Use 2012, 5, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottelin, J.; Heinonen, J.; Junnila, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from flying can offset the gain from reduced driving in dense urban areas. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.R. Does Compact Development Make People Drive Less? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P. Tempest in a teapot: The exaggerated problem of transport-related residential self-selection as a source of error in empirical studies. J. Transp. Land Use 2014, 7, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P.; Peters, S.; Stefansdottir, H.; Strand, A. Causality, not just correlation: Residential location, transport rationales and travel behavior across metropolitan contexts. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 69, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P.; Strand, A.; Wolday, F.; Stefansdottir, H. Residential location, commuting and non-work travel in two urban areas of different size and with different center structures. Progress Plan. 2019, 128, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz-Rau, C.; Scheiner, J. Land-use and transport planning—A field of complex cause-impact relationships. Thoughts on transport growth, greenhouse gas emissions and the built environment. Transp. Policy 2019, 74, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Aviation Shipping—Impacts Europe’s Environment; European Environment Agency (EEA): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Aamaas, B.; Borken-Kleefeld, J.; Peters, G.P. The climate impact of travel behavior: A German case study with illustrative mitigation options. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 33, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamaas, B.; Peters, G.P. The climate impact of Norwegians’ travel behavior. Travel Behav. Soc. 2017, 6, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czepkiewicz, M.; Ottelin, J.; Ala-Mantila, S.; Heinonen, J.; Hasanzadeh, K.; Kyttä, M. Urban structural and socioeconomic effects on local, national and international travel patterns and greenhouse gas emissions of young adults. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 68, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czepkiewicz, M.; Heinonen, J.; Ottelin, J. Why do urbanites travel more than do others? A review of associations between urban form and long-distance leisure travel. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 073001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, I.; White, M.P.; Taylor, T.; Coldwell, D.F.; Gribble, M.O.; Evans, K.L.; Corner, A.; Vardoulakis, S.; Fleming, L.E. ‘Green’ on the ground but not in the air: Pro-environmental attitudes are related to household behaviours but not discretionary air travel. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichert, A.; Holz-Rau, C.; Scheiner, J. GHG emissions in daily travel and long-distance travel in Germany—Social and spatial correlates. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 49, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, C.; Preston, J.M. ‘60-20 emission’—The unequal distribution of greenhouse gas emissions from personal, non-business travel in the UK. Transp. Policy 2010, 17, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhler, S.; Grischkat, S.; Haustein, S.; Hunecke, M. Encouraging environmentally sustainable holiday travel. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2006, 40, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P. Are Short Daily Trips Compensated by Higher Leisure Mobility? Environ. Plan. B: Plan. Des. 2006, 33, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P. Urban Planning: Residential Location and Compensatory Behaviour in Three Scandinavian Cities. In Rethinking Climate and Energy Policies: New Perspectives on the Rebound Phenomenon; Santarius, T., Walnum, H.J., Aall, C., Eds.; Springer Link Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munafò, S. Forme urbaine et mobilités de loisirs: l’effet barbecue sur le grill (Urban form and leisure mobilities: Testing the “barbecue effect” hypothesis). CyberGeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2017, 832. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/28634 (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Große, J.; Fertner, C.; Carstensen, T.A. Compensatory leisure travel? The role of urban structure and lifestyle in weekend and holiday trips in Greater Copenhagen. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottelin, J.; Heinonen, J.; Junnila, S. Rebound effects for reduced car ownership and driving. In Nordic Experiences of Sustainable Planning Policy Practice; Kristjánsdóttir, S., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Enzler, H.B. Air travel for private purposes. An analysis of airport access, income and environmental concern in Switzerland. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 61, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz-Rau, C.; Scheiner, J.; Sicks, K. Travel distances in daily travel and long-distance travel: What role is played by urban form? Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, A.; Holz-Rau, C. Mode use in long-distance travel. J. Transp. Land Use 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K. Troublesome Leisure Travel. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 3087–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfman, N.; Cisternas, P.; López-Vázquez, E.; Maza, C.; Oyanedel, J. Understanding Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in a Chilean Community. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14133–14152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newton, P.; Meyer, D. Exploring the Attitudes-Action Gap in Household Resource Consumption: Does “Environmental Lifestyle” Segmentation Align with Consumer Behaviour? Sustainability 2013, 5, 1211–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Behavioural responses to climate change: Asymmetry of intentions and impacts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, Environmental Concern, and Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2016, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderer Enzler, H.; Diekmann, A. Environment Impact Pro-Environ. Behavior: Correlations to Income Environment Concern; ETH Zurich Sociology Working Papers; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015; No. 9; Available online: http://www.socio.ethz.ch/en/research/energyconsumption.html (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Bruderer Enzler, H.; Diekmann, A. All talk and no action? An analysis of environmental concern, income and greenhouse gas emissions in Switzerland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Siefer, P.; Neaman, A.; Salgado, E.; Celis-Diez, J.; Otto, S. Human-Environment System Knowledge: A Correlate of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15510–15526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davison, L.; Littleford, C.; Ryley, T. Air travel attitudes and behaviours: The development of environment-based segments. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2014, 36, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Árnadóttir, Á.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Heinonen, J. The Geographical Distribution and Correlates of Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors in an Urban Region. Energies 2019, 12, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barr, S.; Shaw, G.; Coles, T.; Prillwitz, J. “A holiday is a holiday”: Practicing sustainability, home and away. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hares, A.; Dickinson, J.; Wilkes, K. Climate change and the air travel decisions of UK tourists. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.; Robbins, D.; Lumsdon, L. Holiday travel discourses and climate change. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorqvist, P.; Langeborg, L. Why People Harm the Environment Although They Try to Treat It Well: An Evolutionary-Cognitive Perspective on Climate Compensation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, G. Vacations and the Quality of Life: Patterns and Structures. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Lazarevski, K.; Yanamandram, V. Quality of life and tourism: A conceptual framework and novel segmentation base. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chester, M.V.; Horvath, A. Environmental assessment of passenger transportation should include infrastructure and supply chains. Environ. Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registers Iceland. Íbúafjöldi Eftir Sveitarfélögum; Þjóðskrá Íslands (Registers Iceland): Reykjavík, Iceland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Valsson, T. Plan. Iceland: From Settlement to Present Times; University of Iceland Press: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2003; p. 480. [Google Scholar]

- Czepkiewicz, M.; Heinonen, J.; Árnadóttir, Á. The Quest for Sustainable Reykjavik Capital Region: Lifestyles, Attitudes, Transport Habits, Well-Being and Climate Impact of Young Adults (SuReCaRe); Report for a Project Funded by Skipulagstofnun Rannsóknar- og þróunarsjóður; Skipulagsstofnun; National Planning Agency of Iceland: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2018; Available online: http://www.skipulag.is/media/pdf-skjol/SuReCaRe.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Kahila, M.; Kyttä, M. SoftGIS as a Bridge-Builder in Collaborative Urban Planning. In Planning Support Systems Best Practice and New Methods; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 95, pp. 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czepkiewicz, M.; Jankowski, P.; Zwoliński, Z. Geo-questionnaire: A spatially explicit method for eliciting public preferences behavioural patterns and local knowledge—An overview. Quaest. Geogr. 2018, 37, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendall, A.; Price, L. Incorporating Time-Corrected Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Vehicle Regulations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 2557–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungbluth, N.; Meili, C. Recommendations for calculation of the global warming potential of aviation including the radiative forcing index. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kander, A.; Jiborn, M.; Moran, D.D.; Wiedmann, T.O. National greenhouse-gas accounting for effective climate policy on international trade. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Große, J.; Olafsson, A.S.; Carstensen, T.A.; Fertner, C. Exploring the role of daily “modality styles” and urban structure in holidays and longer weekend trips: Travel behaviour of urban and peri-urban residents in Greater Copenhagen. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 69, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esri. How Spatial Autocorrelation (Global Moran´s I) Works. Available online: http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.3/tools/spatial-statistics-toolbox/h-how-spatial-autocorrelation-moran-s-i-spatial-st.htm (accessed on 8th November 2019).

- Esri. How Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) Works. Available online: http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.3/tools/spatial-statistics-toolbox/h-how-hot-spot-analysis-getis-ord-gi-spatial-stati.htm (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Newman, P.; Kosonen, L.; Kenworthy, J. Theory of urban fabrics: Planning the walking, transit/public transport and automobile/motor car cities for reduced car dependency. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, P.; Schulman, H.; Ristimäki, M. Urban Form Helsinki Stockholm City Regions: Development Pedestrian, Public Transport and Car Zones; Reports of the Finnish Environment Institute; Finnish Environment Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 2015; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Y.; Agresti, A. Modeling Nonnegative Data with Clumping at Zero: A Survey. JIRSS 2002, 1, 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, D.; Mackenzie, D.; Villouta, E. Modelling skewed data with many zeros: A simple approach combining ordinary and logistic regression. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2005, 12, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, L.; Singh, B.; Strømman, A. The size and range effect: Lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions of electric vehicles. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 054010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.; Norland, I.T. Three Challenges for the Compact City as a Sustainable Urban Form: Household Consumption of Energy and Transport in Eight Residential Areas in the Greater Oslo Region. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2145–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandell, A.; Hall, C.M. Impact of the residential environment on second home use in Finland—Testing the compensation hypothesis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 133, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waygood, E.O.D.; Sun, Y.; Susilo, Y.O. Transportation carbon dioxide emissions by built environment and family lifecycle: Case study of the Osaka metropolitan area. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 31, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahabi, S.A.H.; Miranda-Moreno, L.; Patterson, Z.; Barla, P. Spatio-temporal analysis of car distance, greenhouse gases and the effect of built environment: A latent class regression analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 77, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.; Urry, J.; Axhausen, K. Mobilities, Networks, Geographies; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Axhausen, K.W. Social Networks, Mobility Biographies, and Travel: Survey Challenges. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2008, 35, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frändberg, L. Temporary Transnational Youth Migration and its Mobility Links. Mobilities 2013, 9, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICAO: International Civil Aviation Organization. Available online: https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/Documents/ICAO%20Environmental%20Report%202016.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- ICAO: International Civil Aviation Organization. Available online: https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Peeters, P.; Higham, J.; Kutzner, D.; Cohen, S.; Gössling, S. Are technology myths stalling aviation climate policy? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 44, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viswanathan, V.; Knapp, B.M. Potential for electric aircraft. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.W.; Barrett, S.R.H.; Doyme, K.; Dray, L.M.; Gnadt, A.R.; Self, R.; O’Sullivan, A.; Synodinos, A.P.; Torija, A.J. Technological, economic and environmental prospects of all-electric aircraft. Nat. Energy 2018, 4, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stay Grounded: Conference “Degrowth of Aviation”. Available online: https://stay-grounded.org/conference/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Sharp, H.; Grundius, J.; Heinonen, J. Carbon Footprint of Inbound Tourism to Iceland: A Consumption-Based Life-Cycle Assessment including Direct and Indirect Emissions. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WTO. Tourism taxation: Striking a Fair Deal; The World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Saner, E. Could you Give up Flying? Meet the NO-Plane Pioneers. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2019/may/22/could-you-give-up-flying-meet-the-no-plane-pioneers (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Economist, T. The Greta Effect. Available online: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/08/19/the-greta-effect (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Haenfler, R.; Johnson, B.; Jones, E. Lifestyle Movements: Exploring the Intersection of Lifestyle and Social Movements. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2012, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VTT. LIPASTO—a Calculation System for Traffic Exhaust Emissions and Energy Consumption in Finland. Available online: http://lipasto.vtt.fi (accessed on 9 December 2016).

- US EPA, U. Direct Emissions from Mobile Combustion Sources; US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air and Radiation: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

| Characteristics | Non-Emitters | Middle Group | Top 20% Emitters | Top 5% Emitters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 155 | 370 | 131 | 32 |

| % Graduate and postgraduate education | 31.8% | 36.8% | 38.9% | 43.8% |

| % Speaking four or more languages | 8.4% | 9.5% | 19.1% | 37.5% |

| Average monthly income per CU [k ISK] | 406 | 483 | 536 | 501 |

| % Living in the central pedestrian zone or its fringe | 36.2% | 34.4% | 46.6% | 59.4% |

| Average distance from the main city center [km] | 7.1 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 4.4 |

| % with no car | 16.9% | 8.9% | 13.0% | 21.9% |

| % pedestrian commuters | 15.5% | 11.5% | 13.7% | 25.0% |

| The average yearly number of leisure trips abroad | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7.7 |

| Extent of yearly emissions from international leisure travel [tCO2e] | 0 | 0 to 4.9 | 4.9 to 42.4 | 8.2 to 42.4 |

| Average yearly emissions from international leisure travel [tCO2e] | 0 | 2.4 | 8.1 | 13.6 |

| Model 1: Participation in Emissions | Model 2: PEmissions of Mobile Persons | Model 3: PEmissions of All Persons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1/0) B | [Ln (kg)] β | [kg] B | |

| Descriptive statistics | |||

| Respondents (N) | 655 | 501 | 655 |

| Mean | 76.5% | 7.970 | 2960.448 |

| Standard deviation | 0.770 | 3547.920 | |

| Individual attributes | |||

| Language skills (ref.: Low: one or two languages) | |||

| Medium: three languages | 0.208 | 0.013 | 273.720 |

| High: four languages or more | −0.029 | 0.140 ** | 1885.514 |

| Household attributes | |||

| Household income per CU (ref.: Low: below 375k) | |||

| Medium: 375–550 k | 0.838 ** | 0.135 * | 834.461 |

| High: above 550 k | 0.576 . | 0.194 ** | 920.275 |

| Household type (ref.: Single) | |||

| Couple | 1.322 ** | 0.026 | 705.147 |

| Family | −0.016 | −0.033 | −83.337 |

| Car ownership (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.838 * | −0.035 | −20.272 |

| Urban form at the residential location | |||

| Distance from city center | −0.047 | 0.037 | −12.749 |

| Access to a cabin (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.648 * | −0.030 | 48.763 |

| Private yard (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.359 | −0.043 | −22.826 |

| Socio-psychological attributes related to the environment and leisure travel | |||

| Pro-environmental attitude | 0.070 | 0.043 | 177.995 |

| Climate change awareness | 0.252 . | 0.095 . | 339.509 |

| Cosmopolitan attitude in travel | 0.831 *** | 0.078 | 774.622 |

| Preference for urban vs. natural environments | −0.030 | −0.037 | −9.496 |

| Intercept (B) | −0.006 | 7.855 *** | 2189.580 |

| Model diagnostics | |||

| Pseudo R2 (Nagelkerke) | 0.252 | ||

| R2 (adjusted) | 0.039 | 0.114 | |

| Model 1: PParticipation in Emissions | Model 2: PEmissions of Mobile Persons | Model 3: PEmissions of All Persons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1/0) B | [log (kg)] β | [kg] B | |

| Descriptive statistics | |||

| Respondents (N) | 655 | 565 | 655 |

| Mean | 86.3% | 5.744 | 447.621 |

| Standard deviation | 1.116 | 556.981 | |

| Individual attributes | |||

| Gender (ref.) | |||

| Female | 0.902 ** | −0.017 | −48.841 |

| Household attributes | |||

| Weekly hours worked (ref.: Low: less than 35) | |||

| Medium: 35–45 | −0.228 | 0.024 | −62.359 |

| High: more than 45 | −0.018 | 0.072 | −28.009 |

| Car ownership (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.009 ** | 0.031 | 45.159 |

| Urban form at the residential location | |||

| Neighborhood greenness | 0.458 | −0.011 | 66.696 |

| Access to a cabin (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.269 | 0.136 ** | 119.195 |

| Private yard (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | −0.314 | −0.075 | −73.423 |

| Socio-psychological attributes related to the environment and leisure travel | |||

| Pro-environmental attitude | 0.064 | 0.091 . | 45.435 |

| Climate change awareness | −0.003 | 0.114 * | 29.006 |

| Cosmopolitan attitude in travel | 0.074 | 0.085 . | 40.565 |

| Preference for urban vs. natural environments | −0.331 * | −0.166 *** | −126.482 |

| Intercept (B) | 1.074 . | 5.580 *** | 482.792 |

| Model diagnostics | |||

| Pseudo R2 (Nagelkerke) | 0.092 | ||

| R2 (adjusted) | 0.052 | 0.037 | |

| Model 1: PParticipation in Emissions | Model 2: PEmissions of Mobile Persons | Model 3: PEmissions of All Persons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1/0) B | [log (kg)] β | [kg] B | |

| Descriptive statistics | |||

| Respondents (N) | 693 | 657 | 693 |

| Mean | 94.8% | 6.427 | 1079.194 |

| Standard deviation | 1.345 | 1207.869 | |

| Individual attributes | |||

| Education level (ref.: Low: basic, vocational or secondary) | |||

| Medium: undergraduate | −0.532 | 0.052 | −2.743 |

| High: graduate or postgraduate | −0.264 | 0.120 * | 169.664 |

| Household attributes | |||

| Weekly hours worked (ref.: Low: less than 35) | |||

| Medium: 35–45 | −1.256 | 0.232 *** | 392.779 |

| High: more than 45 | 0.202 | 0.224 *** | 420.050 |

| Household type (ref.: Single) | |||

| Couple | 3.203 ** | 0.031 | 92.013 |

| Family | 2.672 *** | 0.095 . | 5.052 |

| Urban form at the residential location | |||

| Distance from the city center | 0.657 ** | 0.242 *** | 69.630 |

| Access to public transportation (ref.: Zone 1: 10 departures or more within a 5 min walk) | |||

| Zone 2: 4–10 departures within a 5 min walk | −0.868 | 0.037 | −268.973 |

| Zone 3: less than 4 departures within a 5 min walk | −1.005 | −0.011 | −442.473 |

| Zone 4: no bus stop within a 5 min walk | −1.333 | −0.085 | −474.792 |

| Housing type (ref.: Other) | |||

| Apartment | −1.452 . | 0.042 | 213.829 |

| Socio-psychological attributes related to the environment and leisure travel | |||

| Pro-environmental attitude | 0.056 | 0.098 . | 44.530 |

| Climate change awareness | 0.776 . | 0.047 | 25.932 |

| Cosmopolitan attitude in travel | −0.025 | 0.115 ** | 151.372 |

| Preference for urban vs. natural environments | −1.764 *** | −0.017 | −60.950 |

| Socio-psychological attributes related to the residential environment and daily travel | |||

| Suburban preference | 0.059 | 0.156 ** | 200.114 |

| Pro-car attitude | 0.845 . | 0.326 *** | 259.388 |

| Preference for shared housing and transport | 0.147 | −0.116 * | −186.160 |

| Preference for nature and privacy | −1.954 *** | −0.024 | −13.433 |

| Intercept (B) | 4.331 ** | 5.148 *** | 530.285 |

| Model diagnostics | |||

| Pseudo R2 (Nagelkerke) | 0.556 | ||

| R2 (adjusted) | 0.234 | 0.150 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czepkiewicz, M.; Árnadóttir, Á.; Heinonen, J. Flights Dominate Travel Emissions of Young Urbanites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226340

Czepkiewicz M, Árnadóttir Á, Heinonen J. Flights Dominate Travel Emissions of Young Urbanites. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226340

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzepkiewicz, Michał, Áróra Árnadóttir, and Jukka Heinonen. 2019. "Flights Dominate Travel Emissions of Young Urbanites" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226340

APA StyleCzepkiewicz, M., Árnadóttir, Á., & Heinonen, J. (2019). Flights Dominate Travel Emissions of Young Urbanites. Sustainability, 11(22), 6340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226340