A Study on Memory Sites Perception in Primary School for Promoting the Urban Sustainability Education: A Learning Module in Calabria (Southern Italy)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods: A Primary School Learning Module on the Mental Representation of Sites of Memory

2.1. Sites of Memory Subject to Geo-Historical Exploration in the Learning Module

2.2. The Phases of the Learning Module (LM)

- -

- In the first phase we administered an entry questionnaire in the classroom (Appendix A, Table A2); at a later time, we submitted the children to an initial interview for the purpose of detecting Bailly’s influential factors.

- -

- In the second phase, we analyzed the four research themes of the geography of perception, introduced in the LM, through direct observation and a final questionnaire (Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2).

2.3. The Research Questions and the Hypothesis

- (1)

- The possibility to reach and easily access memory sites and any barriers-difficulties encountered; this research question refers to the possibility of subjects being able to freely use the sites of memory and any barriers found that may preclude this or make access to them more difficult.

- (2)

- The aesthetic and functional judgment and the most popular aspects of the sites of memory; this research question refers to the aesthetic and functional judgment that each child has built in his or her own mind using the sites of memory. In addition to influencing the behavior of the child, it could be particularly useful in the area of participatory planning of the territory in order to plan a more sustainable urban environment for its inhabitants.

- (3)

- The orientation skills during the journey from the school to the site of memory [39,40,41,42], defined by Giovanna Axia as “a cognitive process in which the mind constructs and uses more or less complex reference systems to link the points in space” [60]; this research question, therefore, refers to the ability to orientate oneself in the environmental space, a skill strictly dependent on the detected mental image. Furthermore, in the context of this research question the emotional-affective link with the places travelled across during the journey was also investigated (Appendix A, Table A2).

- (4)

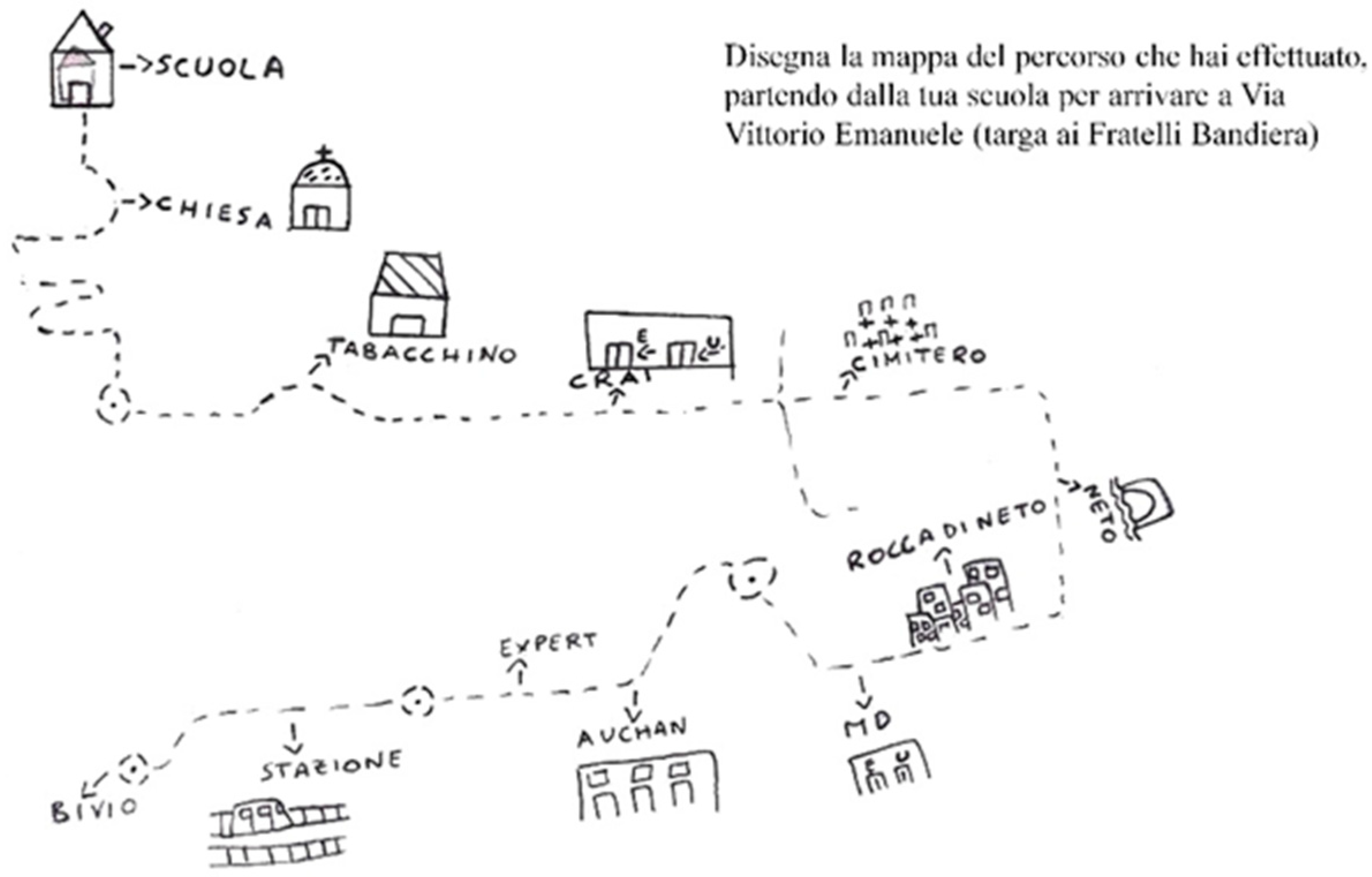

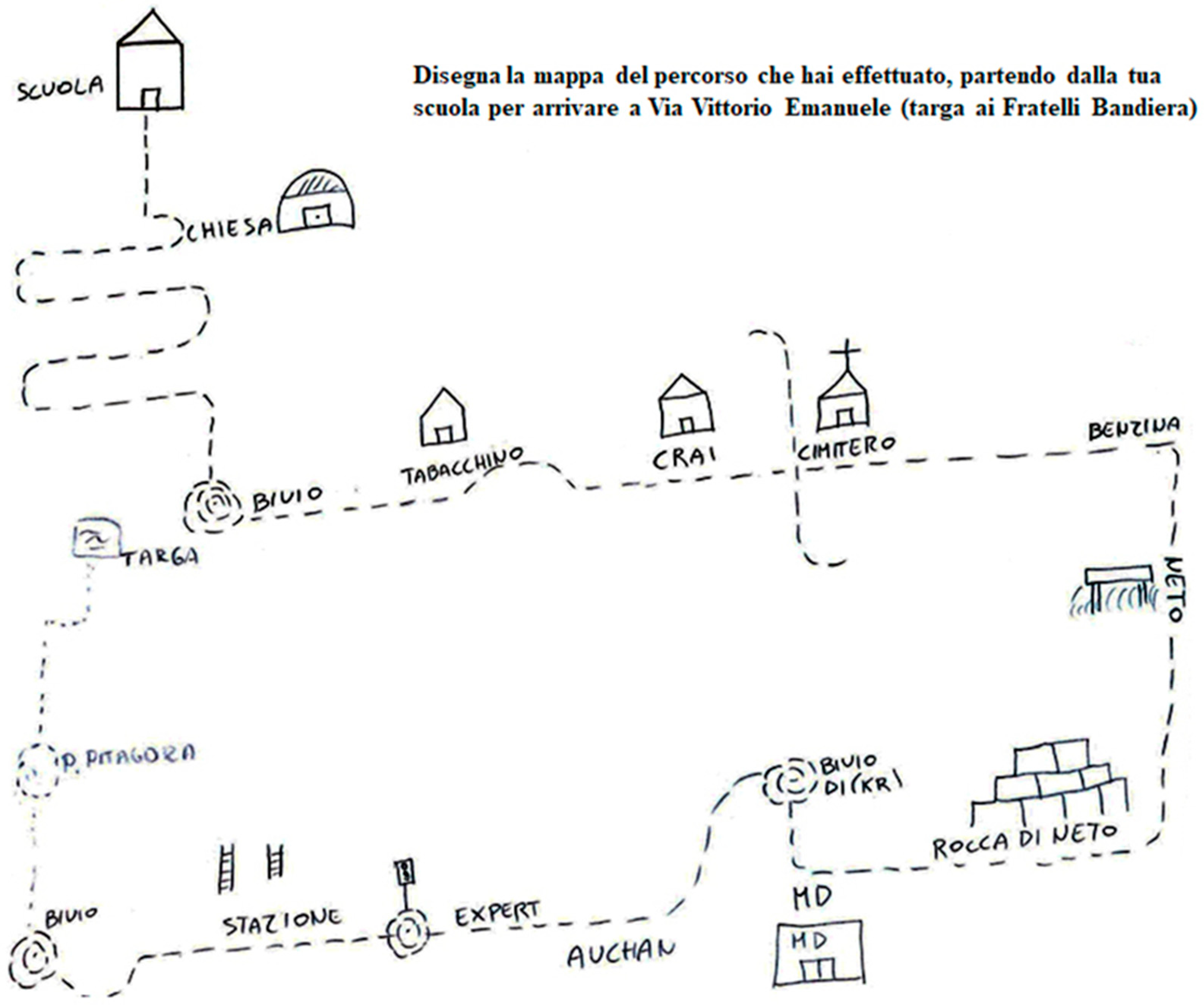

- The elaboration of a mental map [61] of the pathway from school to site of memory. This research question coincides with the technique that allows us to derive the way in which children codify and organize visual-spatial environmental information; it eliminates the problem of the linguistic ability of the subjects, but introduces the one constituted by their graphic capacity. The final products, in fact, are the synthesis between the ability to master the representative medium more or less well and the actual visual-spatial knowledge of the considered environment.

3. Results

3.1. The Mental Representation of the Sites of Memory of Catanzaro, Cosenza and Crotone (Southern Italy): Direct and Indirect Observation and Qualitative Research on the First Three Research Topics

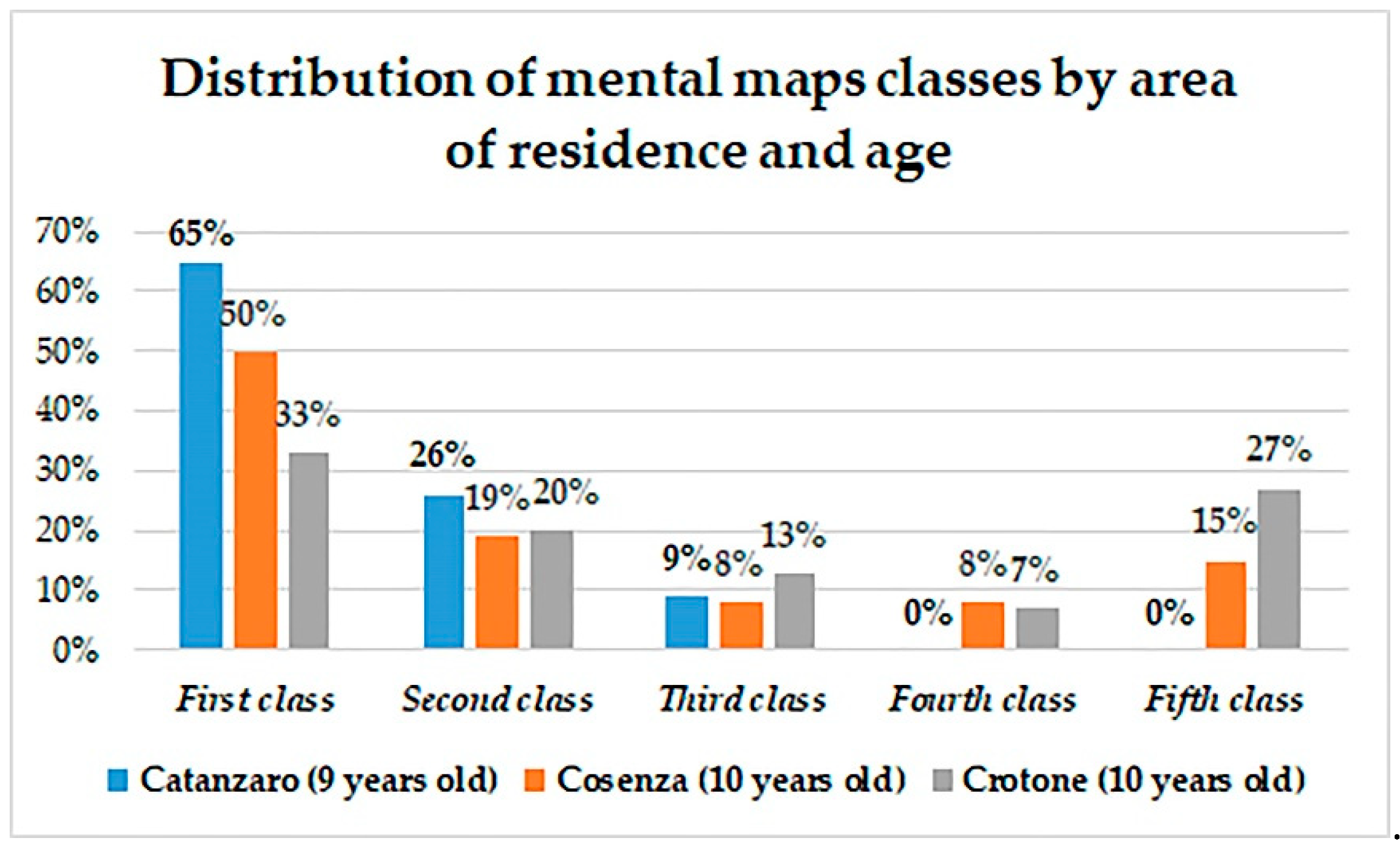

3.2. The Mental Maps and Reference Systems

4. Discussion

4.1. Results Analysis

4.2. The Importance of the Relationship between Geography of Perception and Sustainability Education: Some Research Implications and Reflections

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Learning Module and the Entry/Exit Questionnaires Carried out in the Primary Schools of Crotone, Cosenza and Catanzaro (Calabria, southern Italy)

| Title of the LM | The Mental Representation in Primary School Children in Calabria of Sites of Memory of the Risorgimento |

| School Year | 2012/2013 |

| Pupils involved | Primary school classes of years IV and V of the three provincial capitals of Calabria: Cosenza, Catanzaro, Crotone. |

| Subjects involved | History and Geography |

| Time | 6 months (total time needed to carry out the LM in the three schools of the selected provincial capitals) |

| Spaces necessary and material needed | Inside the School: Classroom, School Building. Outside the school: monuments, buildings, symbolic sites of the Unification of Italy. |

| Main theme | The knowledge of the sites of memory relating to the Risorgimento period, the historical process that led to independence and national unification, the illustrious Italian figures and above all the Calabrian people who lived in that period and contributed to this process. |

| Unit Objective | Learning to interact with peers, communicate with a specific code, orient oneself in space, especially in the context of the city, to develop a critical sense through direct and indirect observation. |

| Specific learning objectives | Know the meaning of “site of memory” and the main aspects of the Risorgimento; to recognize and distinguish the sites of memory, to orient oneself in the urban environment, to take advantage of the places considering their figurability, to assess accessibility. |

| Skills to evaluate | Know how to use specific terms, master empirical knowledge and knowledge acquired during didactic proposals, know how to orient oneself in space. |

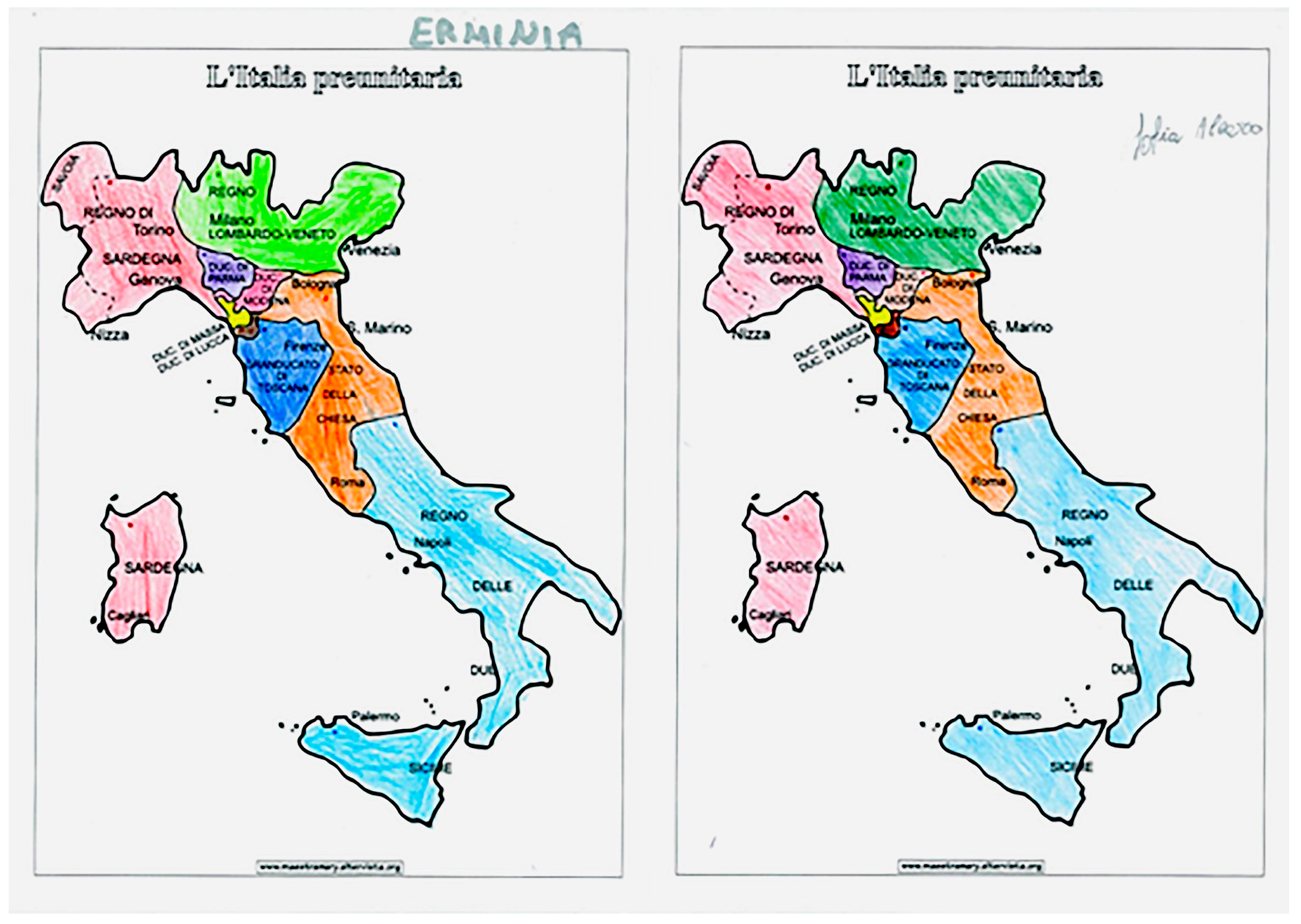

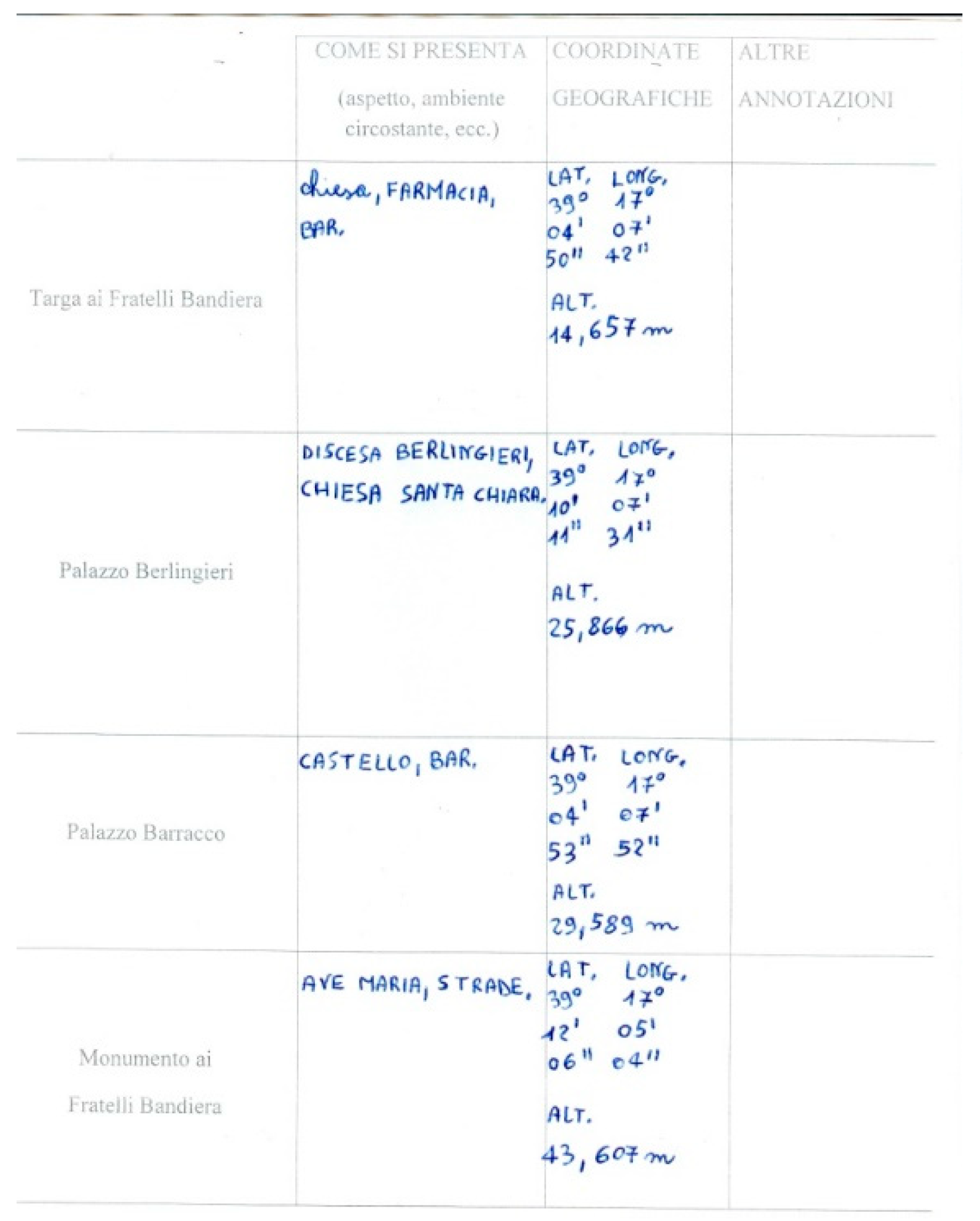

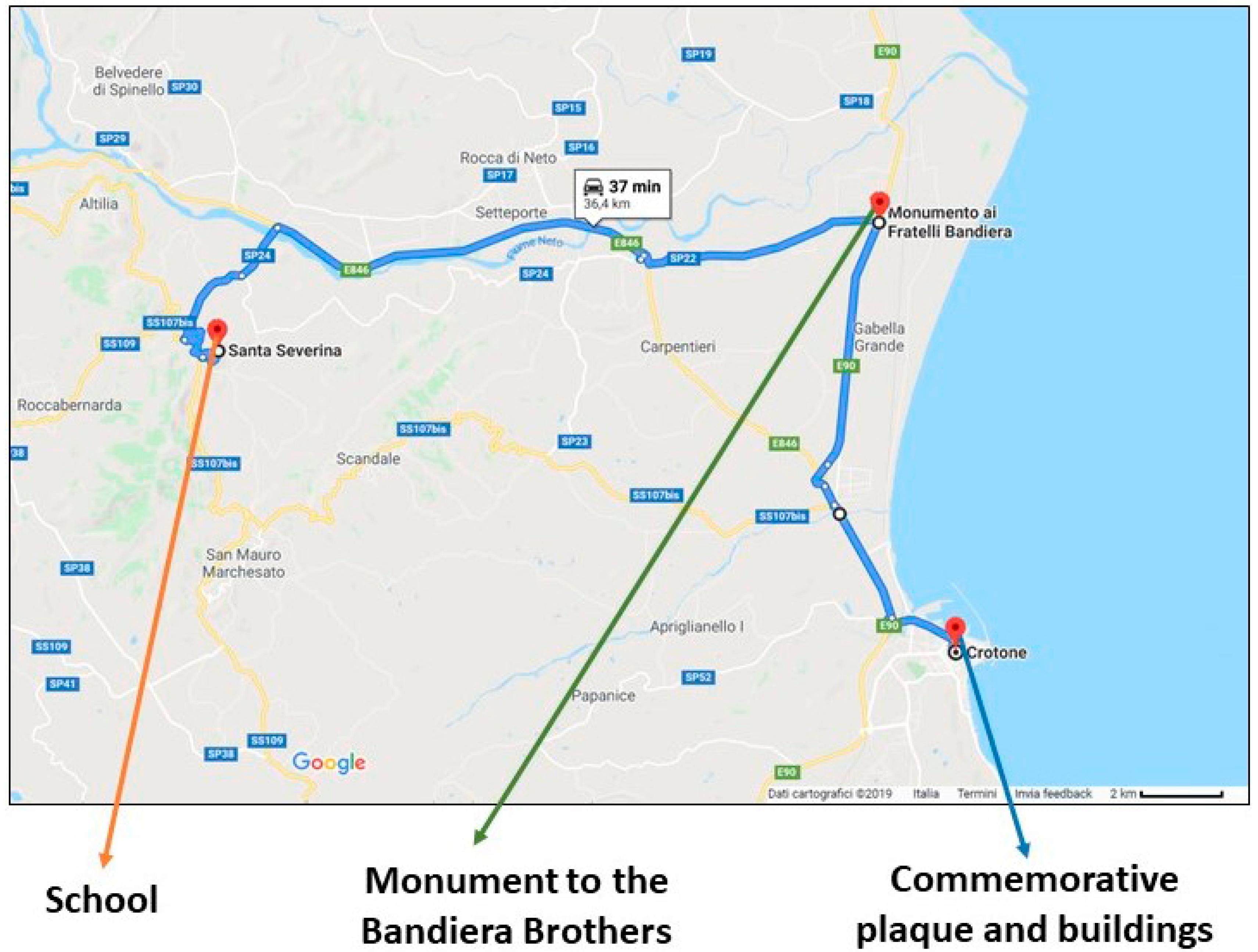

| Learning Pathway | Interview and starting questionnaire to evaluate the initial knowledge of students on places, characters and historical process of Unification of Italy. - Teaching lessons on the subject and delivery of teaching materials: PowerPoint slides to illustrate the historical period of the Risorgimento and the most significant moments in the local context, through the use of the interactive whiteboard (IWB); geographic maps to help the children understand the geographical and political division of pre-unitary Italy and to identify the different states within the Italian geographical region by using different colors; blank map of United Italy with the task of children writing the names of the various regions, highlighting those with special status. - Micro Perception: previewing the map of the intended visit using Google Maps. - Macro perception: Going into the territory and visiting the sites of memory in the urban context, starting from the pupils’ school. - Verification through a final questionnaire; elaboration of the mental map of the school-memory trip. Identifying sites of memory locations and geographic coordinates detected on the territory on a paper map of the city downloaded from Google Maps. |

| Student production | Realization of mental maps of the school-sites of memory route; multiple-choice and open response questionnaires, at the start and at the end of the project. |

| Assessment and evaluation Methods | Questionnaires, verbal descriptions, mental maps |

| Teaching Methodology | Teaching lessons, discovery learning during the educational trip |

| Entry Questionnaire Submitted to Students | |

| Queries | Response Format |

| Q.1 Age Q. 2 Sex | - Open-ended question |

| Q.3 What is a “place of memory”? | Single choice question (A) It is a place where people can go to make their memories resurface; (B) It is a place in the brain where our memories are kept; (C) It is a place where you can go to visit a monument, which is the emblem of a certain important historical period of our country. |

| Q.4 Do you think the “places of memory” remember something of that city? | Single choice question (A) Yes, because they remember the laws of the place; (B) Yes, because they remember the origins and the path that led us to be what we are today; (C) No. |

| Q.5 In your city the “places of memory” are present? | Yes/No |

| Q.6 In which year was the 150th anniversary of the Unification of Italy celebrated? | Single choice question (A) 2009; (B) 2010; (C) 2011. |

| Q.7 Why is the Unit of Italy celebrated? | Single choice question (A) Because in the past Italy was politically administered by various foreign sovereigns; (B) Because Italy has a Constitution based on the principle of equality and therefore all citizens must be equal before the law; (C) Because in the past there were two Italys: Northern Italy and Southern Italy. |

| Q.8 Have you ever visited monuments, squares, museums, or other places that remind you of the Unification of Italy in your city? | - Yes/No |

| Q.9 What values did the Unit of Italy transmit? | Single choice question (A) Love for the homeland, reconsideration of the history of Italy, awareness of belonging to a great nation; (B) Economic advantages throughout the nation; (C) No value, the situation remained unchanged. |

| Q.10 Do you think the memory sites are important? | Single choice question (A) Yes, because they represent the common heritage of values and ideals matured in the Risorgimento; (B) No, because it is not important to remember the past of one’s origins. |

| Q.11 In every city, in your opinion, why should there be at least one “place of memory”? | Single choice question (A) Because every person can feel not only a citizen of his own city, but also a citizen of his own country, since knowing his own local history one can understand the national history; (B) Because belonging to the same territory, we all have the right to claim one; (C) Because people can tell what they saw in that place. |

| Q.12 Do you think the Unity of Italy has brought only advantages? | Yes/No |

| Q.13 Motivate your answer. | - Open-ended questions |

| Exit Interview Questionnaire | |

| Topics | Open Questions |

| 1. The possibility to reach and easily access memory sites and any barriers-difficulties encountered | Q.1 After visiting some “memory sites” of the city of…, you think that the places you visited are easily reachable and accessible on foot or by means of transport, or that there are “barriers-difficulties” that freely prevent you from visiting it? |

| 2. The aesthetic and functional judgment and the most popular aspects of the memory sites; | Q.2 Express your aesthetic judgment on the visited memory sites. Q.3 Among the memory sites visited, which of them has affected you the most? Q.4 Describe the aspects that were most to your liking from each place you visited. |

| 3. Orientation skills and emotional-affective ties with the territory | Q.5 Has the visit of the memory sites of… aroused in your mind some memories that recall emotional ties with that territory? This topic has also been examined by considering the behavior of children during educational output and analysis of mental maps |

| 4. The elaboration of a mental map of the pathway from school to site of memory. | Q.6 Draw the map of the route you have taken in the city of... |

Appendix B. Some Materials Used in the Context of the Learning Module

References

- Nora, P. (Ed.) Les Lieux de Mémoire I; Gallimard: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, R.M. Geographic space perception: Past approaches and future prospects. Prog. Geogr. 1970, 2, 65–108. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, R. Espace, perception et. Comportement. L’Espace Géographique 1974, 3, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, A.S. L’organisation urbaine. In Théories et. Modèles; Centre de Recherche d’Urbanisme: Paris, France, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Frémont, A. La Région Espace Vécu; PUF: Paris, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Brusa, C. Geografia e Percezione Dell’ambiente: Varese Vista Dagli Operatori Dell’ente Pubblico Locale; Giappichelli: Turin, Italy, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cesa-Bianchi, M. Ambiente e Percezione: Ricerca Geografica e Percezione Dell’ambiente; Geipel, R., Cesa-Bianchi, M., Eds.; Unicopli: Milan, Italy, 1980; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, E. Comportamento e percezione dello spazio ambientale. Dalla Behavioral Revolution al Paradigma Umanistico. In Aspetti e Problemi Della Geografia; Pellegrini, G.C., Ed.; Marzorati: Settimo Milanese, Italy, 1987; pp. 545–598. [Google Scholar]

- Lando, F. La geografia della percezione. Origini e fondamenti epistemologici. Riv. Geogr. Ital. 2016, 123, 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca, L. Prefazione. In Immagini di Padova: Analisi Delle Percezioni Della Città e dei Suoi Quartieri in Alunni di Classi Terza e Quinta Della Scuola Primaria; Lovigi, S., Ed.; Cleup: Padua, Italy, 2013; pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, A.W.; White, S.H. The Development of Spatial Representations of Large-Scale Environments. In Advances in Child Development; Reese, H.W., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lando, F. Fatto e Finzione: Geografia e Letteratura; Etaslibri: Milan, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lovigi, S. Percepire il territorio per potervi agire. Analisi delle mappe mentali del quartiere di residenza in alunni di classi terza e quinta della scuola primaria, Ambiente Società Territorio. Geogr. Nelle Scuole 2011, 56, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Frémont, A. Aimez-Vous la Géographie; Éditions Flammarion: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Best, E. Pour une Pédagogie de L’éveil; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. Geography, experience and imagination: Towards a geographical epistemology. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1961, 51, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Humanism, phenomenology and geography. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1977, 67, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y. Geography, phenomenology and the study of human nature. Can. Geogr. 1971, 15, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y. Comment in reply. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1977, 67, 179–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttimer, A. Comment in reply. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1977, 67, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, D.C.D. La geografia umanista. In Concetti Della Geografia Umana I; Bailly, A., Ed.; Patron: Bologna, Italy, 1989; pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.K. Terrae incognitae: The place of imagination in geography. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1947, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, M.; John, K. Wright and human nature in geography. Geogr. Rev. 1993, 83, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lando, F. La geografia umanista: un’interpretazione. Riv. Geogr. Ital. 2012, 119, 259–289. [Google Scholar]

- Gavinelli, D. Introduzione (sessione 8-Geografia e letteratura. Luoghi, scritture, paesaggi reali e immaginari). In L’apporto Della Geografia tra Rivoluzioni e Riforme: Atti del XXXII Congresso Geografico Italiano (Roma, 7–10 giugno 2017); Salvatori, F., Ed.; AGEI: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Brosseau, M. Geography’s Literature. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1994, 18, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioli, M.; Morri, R. Tra geografia e letteratura: Realtà, finzione, territorio. In Letteratura e Geografia: Parchi Letterari, Spazi Geografici e Suggestioni Poetiche nel ‘900 Italiano, Quaderni del ‘900; Mancini, S., Vitali, L., Eds.; Fabrizio Serra Editore: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli d’Allegra, D. I Parchi Letterari: Geografia e Letteratura Nella Didattica Modulare: Atti del XXVIII Congresso Geografico Italiano (Roma 18–22 Giugno 2000); Edigeo: Rome, Italy, 2003; pp. 2136–2150. [Google Scholar]

- Persi, P. Parchi letterari e professionalità geografica: Il territorio tra trasfigurazione e trasposizione utilitaristica. Geotema 2003, 20, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.; Daniels, E. The Iconography of Landscape: Essays of the Symbolic Representation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, A.; Da Silva, E.L. Paesaggio culturale e letteratura: Le memorie dei viaggiatori stranieri in Minas Gerais nel XIX secolo. In L’apporto Della Geografia tra Rivoluzioni e Riforme: Atti del XXXII Congresso Geografico Italiano (Roma, 7-10 Giugno 2017); Salvatori, F., Ed.; AGEI: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 621–627. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramellini, G. La Geografia dei Viaggiatori: Raffigurazioni Individuali e Immagini Collettive nei Resoconti di Viaggio; Unicopli: Milan, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi, F. L’esperIenza del Viaggiar: Geografi e Viaggiatori del XIX e XX Secolo; Giappichelli: Turin, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- De Vecchis, G. Verso L’altro e L’altrove; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, L.; Papotti, D. (Eds.) Alla Fine del Viaggio; Diabasis: Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, C. La Geografia Nella Scuola Primaria: Contenuti, Strumenti, Didattica; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ronza, M. Educare ai beni culturali: Geografia, identità e sostenibilità. In Educare al Territorio, Educare il Territorio. Geografia per la Formazione; Giorda, C., Puttilli, M., Eds.; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2011; pp. 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Istituto Treccani. Enciclopedia Italiana di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti. 2019. Available online: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/risorgimento/ (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Giorda, C. Il Mio Spazio nel Mondo. Geografia per la Scuola Dell’infanzia e Primaria; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reclus, E. L’Homme et la Terre; Librairie Universelle: Paris, France, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, M.; De Pascale, F. Children’s Geographies. La rappresentazione mentale dei luoghi della memoria del Risorgimento in bambini di scuola primaria: Il caso studio di Crotone. Geotema 2018, 57, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- De Pascale, F. La percezione dei luoghi e dei personaggi dell’Unità d’Italia in Calabria: Il valore educativo di un approccio storico-geografico con il supporto di strumenti GIS Open Source. In Geografie di Oggi. Metodi e Strategie tra Ricerca e Didattica; Alaimo, A., Aru, S., Donadelli, G., Nebbia, F., Eds.; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2015; pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, L. La Percezione dei Luoghi Della Memoria nel Contesto Urbano di Crotone. Master’s Thesis, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici, Corso di laurea in Scienze della Formazione Primaria, Università della Calabria, Rende, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, L.M. I volti di Villa Margherita; La Rondine Edizioni: Catanzaro, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Celebrations for the 150th Anniversary of the Unification of Italy. Page Dedicated to the Monument to Francesco Stocco. Available online: https://www.italiaunita150.it/catanzaro-monumento-a-francesco-stocco/ (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- De Pascale, F. Lo Studio dei Luoghi Della Memoria e Dei Terremoti in Calabria Attraverso la Geografia Della Percezione, la Geoetica e le Nuove Tecnologie, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Calabria, Rende, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sculco, N. Per L’inaugurazione di due Lapidi Commemorative in Cotrone il 27 Gennaio 1907; Stabilimento Tipografico Pirozzi: Crotone, Italy, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Intrieri, L. Il Risorgimento. In Storia, Cultura, Economia; Mazza, F., Ed.; Rubbettino Editore: Cosenza, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Meluso, S. Il Voto del Coraggio: La Guida Calabrese dei Fratelli Bandiera; Ene: Cosenza, Italy, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Meluso, S. Sbarco e Cattura dei Fratelli Bandiera e Compagni; Fiore, S.G., Ed.; Museo Demologico: Cosenza, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, C. Eventi Risorgimentali; Casa del Libro: Cosenza, Italy, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Pierantoni, R. Storia dei Fratelli Bandiera; Casa editrice L.F. Cogliati: Milano, Italy, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, G. Dizionario dei Luoghi Della Calabria; Edizioni Frama’s: Catanzaro, Italy, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Visalli, V. I Calabresi nel Risorgimento Italiano. In Storia Documentata Delle Rivoluzioni Calabresi dal 1799 al 1862; Walter Brenner Editore: Cosenza, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Perussia, F. La percezione dell’ambiente: Una rassegna psicologica. In Ricerca Geografica e Percezione Dell’ambiente; Geipel, R., Cesa-Bianchi, M., Eds.; Unicopli: Milan, Italy, 1980; pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- De Pascale, F.; D’Amico, S. Historical Memory and Natural Hazards in Neogeographic Mapping Technologies. In The Digital Arts and Humanities. Neogeography Social Media and Big Data Integrations and Applications; Travis, A.C., Lünen, A.V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, F. Geoethics and Sustainability Education Through an Open Source CIGIS Application: The Memory of Places Project in Calabria, Southern Italy, as a Case Study. In Going Beyond-Sustainability in Heritage Studies No 2; Albert, M., Bandarin, F., Pereira Roders, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovigi, S. Immagini di Padova: Analisi Delle Percezioni Della Città e dei Suoi Quartieri in Alunni di Classi Terza e Quinta Della Scuola Primaria; Cleup: Padua, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Axia, G. La Mente Ecologica: La Conoscenza Della Mente nel Bambino; Giunti Barbera: Florence, Italy, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, P.; White, R.R. Mental Maps; Penguin: Hardmondsworth, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. Lo Sviluppo Mentale del Bambino e Altri Studi di Psicologia; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. L’immagine Della Città; Marsilio: Venice, Italy, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M. Psicologia Ambientale e Architettonica: Come L’ambiente e L’architettura Influenzano la Mente e il Comportamento; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, R.M.; Stea, D. Cognitive maps and spatial behavior: Process and products. In Image and Environments: Cognitive Mapping and Spatial Behaviour; Downs, R.M., Stea, D., Eds.; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973; pp. 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bailly, A.; Béguin, H. Introduction à la Géographie Humaine; Masson: Paris, France, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, J.; Kraftl, P. What else? Some more ways of thinking and doing ‘Children’s Geographies’. Child. Geogr. 2006, 4, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, S. Geografia dei Bambini Luoghi, Pratiche e Rappresentazioni; Guerini e Associati: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Antronico, L.; Coscarelli, R.; De Pascale, F.; Muto, F. Geo-hydrological risk perception: A case study in Calabria (Southern Italy). Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 25, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antronico, L.; Coscarelli, R.; De Pascale, F.; Condino, F. Social Perception of Geo-Hydrological Risk in the Context of Urban Disaster Risk Reduction: A Comparison between Experts and Population in an Area of Southern Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, F.; Antronico, L.; Coscarelli, R. La percezione del rischio idrogeologico in Calabria: Il caso studio della Costa degli Dei. Arch. Di Studi Urbani E Reg. 2019, 124, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Maruna, M.; Rodic, D.M.; Colic, R. Remodelling urban planning education for sustainable development: The case of Serbia. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 658–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamedica, I. Conoscere e Pensare la città; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peron, E.M.; Falchero, S. Ambiente e Conoscenza. In Aspetti Cognitivi Della Psicologia Ambientale; La Nuova Italia Scientifica: Rome, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights. Convention on the Rights of the Child: Adopted and Opened for Signature, Ratification and Accession by General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 Entry into Force 2 September 1990, in Accordance with Article 49; UN Human Right: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, EU Law. Green Paper on the Urban Environment: Communication from the Commission to the Council and Parliament; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Movement “Città educative”, Carta Delle Città Educative. In Proceedings of the Congresso Internazionale delle Città Educative, Barcellona, Spain, 26–30 Novembre 1990.

- Commissione Comunità Europee. Proposta per un Programma di Ricerca Sulle Città Senza Auto; Edizione: Treviso, Italiana, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Agenda 21. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. [Google Scholar]

- The Aalborg Charter. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Sustainable Cities & Towns, Aalborg, Denmark, 27 May 1994.

- Mason, E. Educazione all’orientamento e intelligenza spaziale. In Educare al Territorio, Educare il Territorio. Geografia per la Formazione; Giorda, C., Puttilli, M., Eds.; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2011; pp. 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Formae Mentis; Feltrinelli: Milan, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Law 28 March 2003, n. 53, Delegation to the Government for the Definition of the General Norms on Education and the Essential Levels of the Performances in Subject of Education and Professional Formation. Available online: https://archivio.pubblica.istruzione.it/normativa/2004/legge53.shtml (accessed on 27 October 2019).

- Hayward, B. Children Citizenship and Environment Nurturing a Democratic Imagination in a Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Pascale, F. Percorsi interdisciplinari STEAM per la scuola del futuro, Ambiente Società Territorio. Geogr. Nelle Scuole 2018, 18, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- De La Garza, A.; Travis, C. (Eds.) The Steam Revolution: Transdisciplinary Approaches to Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Humanities and Mathematics; Springer Geography: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Otero, A.J.; de Lázaro y Torres, M.L. Spatial data infrastructures and geography learning. Eur. J. Geogr. 2017, 8, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zwartjes, L.; de Lázaro y Torres, M.L. Geospatial Thinking Learning Lines in Secondary Education: The GI Learner Project. In Geospatial Technologies in Geography Education; De Miguel Gonzalez, R., Donert, K., Koutsopoulos, K., Eds.; Key Challenges in Geography; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, T. Weathering time: Walking with young children in a changing climate. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Provincial Capitals (Calabria, Southern Italy) | School | Class | Sites of Memory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catanzaro | Convitto Nazionale “Pasquale Galluppi,” located in Catanzaro (Italy); | Fourth-year primary school class; age: 9 years old | Villa Trieste; Monument to Francesco Stocco |

| Cosenza | Istituto Comprensivo “Rende Centro,” located in Rende (Cosenza, Italy) | Fifth-year primary school class; age: 10 years old | Statua della Liberta (Statue of Liberty); Palazzo del Governo (Government’s Building); Palazzo Arnone (Arnone Building); Ara dei Fratelli Bandiera (Altar of the Bandiera Brothers); Catena Spezzata (Broken Chain) |

| Crotone | Istituto omnicomprensivo “Diodato Borrelli” of Santa Severina (Crotone, Italy) | Fifth-year primary school class; age: 10 years old | Plaque for the Bandiera Brothers; Palazzo Berlingieri; Palazzo Barracco; Monument to the Bandiera Brothers |

| Research Questions | Cosenza | Catanzaro | Crotone |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) The possibility to reach and easily access memory sites and any barriers-difficulties encountered | The places visited are easily accessible both on foot and by a means of transport; there are no “barriers” that prevent them from visiting these sites freely | Difference in accessibility between the first route, from school to the monument to Francesco Stocco and the second, from school to Villa Trieste | The sites of memory are easily accessible, as there are no “barriers-difficulties;” some are more easily accessible on foot (given the narrow lanes) and others need, instead, a means of transport |

| Factors that influence the children’s perception of connection to this research theme | Environmental factors | Environmental factors | Environmental factors |

| (2) The aesthetic and functional judgment and the most popular aspects of the sites of memory | Positive opinion of the “sites of memory,” emphasizing that, despite the passing of time, they are still well preserved; childhood memories, experiences with parents, grandparents, as well as references to films seen on television. | Satisfaction and perception of wonder in the visit of Villa Trieste, previously experienced with family members; Children did not like Piazza Stocco because of the accessibility problems of the monument located in the center of a roundabout | A positive aesthetic judgment to the various places visited, which, despite the wear and tear, the children said are still in good condition and are “well cared for.” The children had never before visited these places. |

| Factors that influence the children’s perception of connection to this research theme | Psychological factors | Psychological and environmental factors | Environmental factors |

| (3) The orientation skills during the journey from the school to the site of memory | Presence of numerous psychological landmarks in mental maps; previous use of the places in a controlled way with the presence of adults/family members; appreciable way finding thanks to the familiarity of the places due to the residence of the students in the city. | Presence of numerous psychological landmarks in mental maps; previous use of the places in a controlled way with the presence of adults/family members; appreciable way finding thanks to the familiarity of the places due to the residence of the students in the city. | Presence of numerous psychological landmarks in mental maps; not enough way finding because of the residence of the students in neighboring areas and the absence of previous visits. |

| Factors that influence the children’s perception of connection to this research theme | Psychological and environmental factors | Psychological and environmental factors | Psychological and environmental factors |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernardo, M.; De Pascale, F. A Study on Memory Sites Perception in Primary School for Promoting the Urban Sustainability Education: A Learning Module in Calabria (Southern Italy). Sustainability 2019, 11, 6379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226379

Bernardo M, De Pascale F. A Study on Memory Sites Perception in Primary School for Promoting the Urban Sustainability Education: A Learning Module in Calabria (Southern Italy). Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226379

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernardo, Marcello, and Francesco De Pascale. 2019. "A Study on Memory Sites Perception in Primary School for Promoting the Urban Sustainability Education: A Learning Module in Calabria (Southern Italy)" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226379