The Relationship between Social Responsibility and Business Performance: An Analysis of the Agri-Food Sector of Southeast Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. CSR As a Multidimensional Phenomenon: Approaches and Conceptualization

2.2. CSR in the Agri-Food Sector

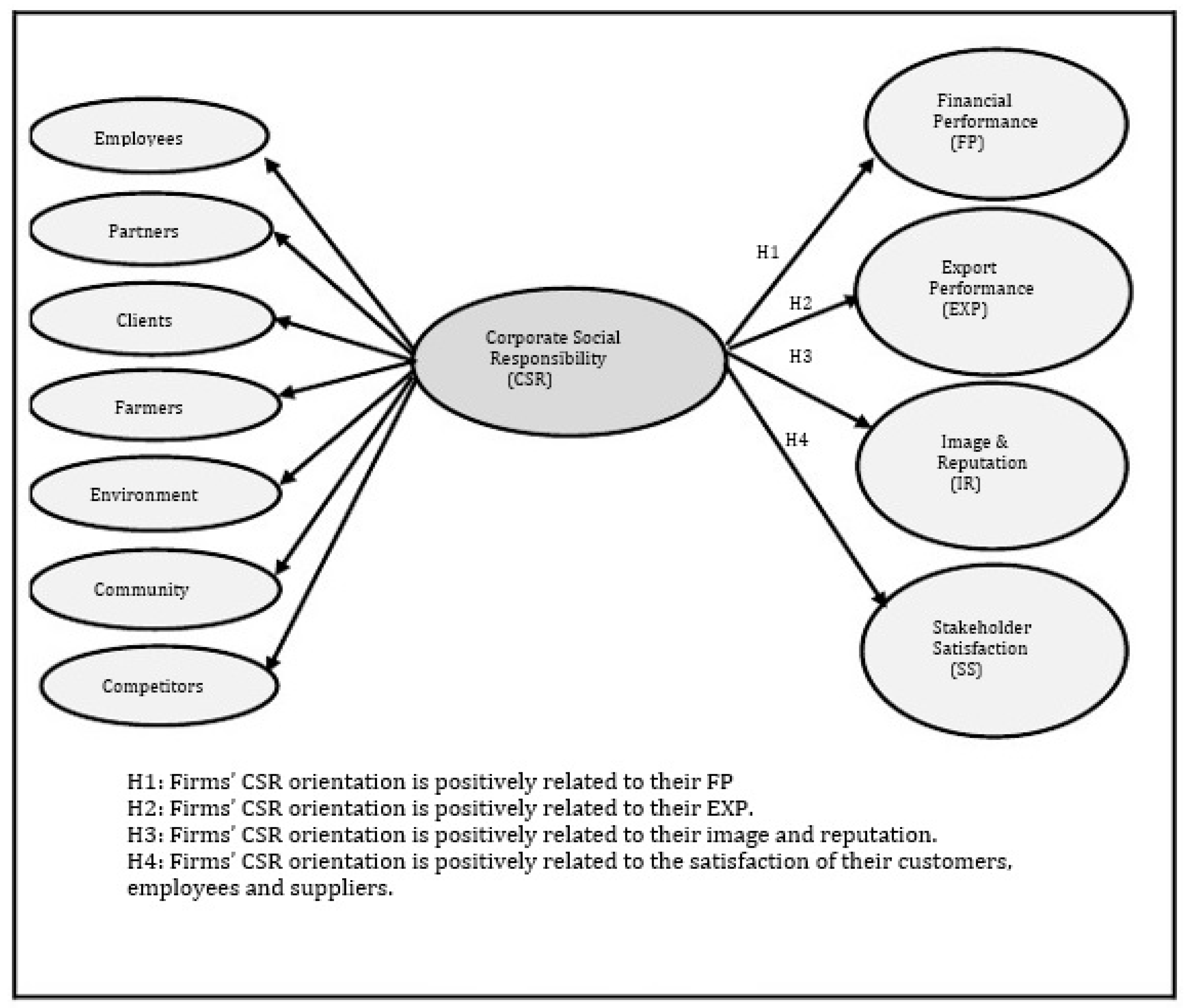

3. Hypothesis

3.1. CSR and FP

3.2. CSR and EXP

3.3. CSR and Image and Reputation

3.4. CSR and Satisfaction of Relevant Stakeholders

4. Methodology

4.1. Measurement

4.2. Data Collection and Sample

5. Results

5.1. Identification and Evaluation of the Measurement Model

5.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model

6. Discussion

6.1. Theorical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

7. Limitations and Proposals for Future Research Lines

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Influence Firm Performance of Indian Companies? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, L.E.; O’Bannon, D.P. The Corporate Social-Financial Performance Relationship. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, R.M.; Hayibor, S.; Agle, B.R. The Relationship between Social and Financial Performance. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The Corporate Social Performance-Financial Performance Link. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attamimi, A.A.B.; Ameer, R. Readability of Corporate Social Responsibility Communication in Malaysia. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeyono, J.; Samy, M.; Bampton, R. An examination of corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A study of the top 50 Indonesian listed corporations Positivism to Social Constructivism: An emerging trend for CSR researchers View project. J. Glob. Responsib. 2011, 2, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Kobeissi, N.; Liu, L.; Wang, H. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Financial Performance: The Mediating Role of Productivity. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Friede, G. The Robustness of the Corporate Social and Financial Performance Relation: A Second-Order Meta-Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 583–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Theory of the Firm Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.J.; Mahon, J.F. The Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Financial Performance Debate. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, V.L.; Freire, F.d.S.; Vasconcellos, F.C. Corporate social responsibility, firm value and financial performance in Brazil. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.L.; Ho, J.A.; Sambasivan, M. Impact of Corporate Political Activity on the Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: A Dynamic Panel Data Approach. Sustainability 2018, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, S.; Bakr, A. The curvilinear relationship between corporate social performance and financial performance. J. Glob. Responsib. 2019, 10, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Measuring Corporate Citizenship in Two Countries: The Case of the United States and France. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.; Schlesinger, M.W. Dimensionalidad de la Responsabilidad Social Empresarial percibida y sus efectos sobre la Imagen y la Reputación: Una aproximación desde el modelo de Carroll. Estud. Gerenc. 2008, 24, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Russo, A.; Tencati, A.; Vurro, C. Deconstructing the Relationship Between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Social Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakou, A.; Jackson, G. Corporate Social Responsibility in Western Europe: An Institutional Mirror or Substitute? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W. Corporate sustainable development: Testing a new scale based on the mainland Chinese context. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 28, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st Century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Murphy, P.E.; Gruber, V. Consumers’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, A.D.; Daponte, R.R.; Vázquez, E.G. Valoración de la rsc por el consumidor y medición de su efecto sobre las compras. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2014, 54, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Lam, C.F.; Chau, K.Y.; Shen, H.W.; Wang, X. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility in Gambling Industry: Multi-Items Stakeholder Based Scales. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I. Multi-Item Stakeholder Based Scale to Measure CSR in the Banking Industry. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2014, 2, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Erramilli, M.K.; Dev, C.S. Market orientation and performance in service firms: Role of innovation. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C. Shared, Competitive, and Comparative Advantages: A Competence-Based View of Industrial-District Competitiveness. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2004, 36, 2227–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Garrigós, F.; Palacios, D. Estrategias competitivas y desempeño empresarial: Estudio comparativo de los modelos de Robinson & Pearce y Miles & Snow en el sector hotelero Español. IEDEE 2007, 13, 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Alafi, K.; Hasoneh, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility Associated With Customer Satisfaction and Financial Performance a Case Study with Housing Banks in Jordan. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 102–115. [Google Scholar]

- Galbreath, J.; Shum, P. Do customer satisfaction and reputation mediate the CSR–FP link? Evidence from Australia. Aust. J. Manag. 2012, 37, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Hatch, N.W. Researching Corporate Social Responsibility: An Agenda for the 21st Century. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyder, M.; Theuvsen, L. Corporate Social Responsibility in Agribusiness: Empirical Findings from Germany. In A resilient European food industry and food chain in a challenging world. In Proceedings of the European Association of Agricultural Economists (EAAE), 113th EAAE Seminar, Chania, Greece, 3–6 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, B.; Wocken, C.; Spiller, A. Relationship quality in agri-food chains: Supplier management in the German pork and dairy sector. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2006, 6, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Akridge, J.T.; Gray, A.; Boehlje, M.; Widdows, R. An Evaluation of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) Practices among Agribusiness Firms. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. 2007, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmers, H.; Omta, O.; Haverkamp, D.J. A Stakeholder View on Sustainable Food and Agribusiness Chain Development. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual IAMA Conference, Montreux, Switzerland, 12–15 June 2004; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40122187 (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Schiebel, W.; Pöchtrager, S. Corporate ethics as a factor for success—The measurement instrument of the University of Agricultural Sciences (BOKU), Vienna. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2003, 8, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christensen, L.J.; Peirce, E.; Hartman, L.P.; Hoffman, W.M.; Carrier, J. Ethics, CSR, and Sustainability Education in the Financial Times Top 50 Global Business Schools: Baseline Data and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 73, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.M. The Corporate Social Policy Process: Beyond Business Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Corporate Social Responsiveness. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1987, 29, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, P.N.; Gundlach, G.T. Handbook of Marketing and Society, 1st ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.C. Corporate Social Responsibility: Whether or How? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, R.; Hansen, E.; Anderson, R. Students’ perceptions regarding CSR success of the US forest products industry. Soc. Responsib. J. 2010, 6, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Mackay, J. Auditing for the environment. Manag. Audit. J. 2003, 18, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, B.J.; Awa, H.O.; Enuoh, R.O. CSR-HRM Nexus: Defining the Role Engagement of the Human Resources Professionals. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Perspective; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; Sillanpää, M. The Stakeholder Corporation: A Blueprint for Maximizing Stakeholder Value; Pitman: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, H.; Theuvsen, L. Corporate Social Responsibility in Agribusiness: Literature Review and Future Research Directions. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.; Swinton, S.M. Reconciling agricultural productivity and environmental integrity: A grand challenge for agriculture. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2005, 3, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Vandermeulen, V.; Mettepenningen, E.; Verspecht, A. Multifunctionality of Agriculture: A Review of Definitions, Evidence and Instruments. Living Rev. Landsc. Res. 2007, 1, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atance, I.; Tió, C. La multifuncionalidad de la agricultura: Aspectos económicos e implicaciones sobre la política agraria. Estud. Agrosoc. Pesq. 2000, 189, 29–48. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/165041/2/pdf_reeap-r189_02.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2018).

- Abler, D. Multifunctionality, Agricultural Policy, and Environmental Policy. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2004, 33, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gopalakrishnan, S. Unraveling the links between dimensions of innovation and organizational performance. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2000, 11, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.J.; DeVinney, T.M.; Yip, G.S.; Johnson, G. Measuring Organizational Performance: Towards Methodological Best Practice. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 718–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferraz, F.A.D.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Ferraz, F.A.V.G.D. Measurement tool to assess the relationship between corporate social responsibility, training practices and business performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Santos, M.; Lucianetti, L.; Bourne, M. Contemporary performance measurement systems: A review of their consequences and a framework for research. Manag. Acc. Res. 2012, 23, 79–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Zou, S. Marketing Strategy-Performance Relationship: An Investigation of the Empirical Link in Export Market Ventures. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Vitaliano, D.F. An Empirical Analysis of the Strategic Use of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2007, 16, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boehe, D.M.; Cruz, L.B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Product Differentiation Strategy and Export Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, U. Gesellschaftliche Verantwortung als Business Case: Ansatze, Defizite und Perspektiven der deutschsprachigen Betriebswirtschaftslehre. In Betriebswirtschaftslehre und Gesellschaftliche Verantwortung: Mit Corporate Social Responsibility zu mehr Engagement, 1st ed.; Schneider, U., Steiner, P., Eds.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004; pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Roy, M.-J. Sustainability in Action: Identifying and Measuring the Key Performance Drivers. Long Range Plan. 2001, 34, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.A.; London, T. How corporations and environmental groups cooperate: Assessing cross-sector alliances and collaborations. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barin, L.; Boehe, D.M.; Ogasavara, M.H. CSR-based Differentiation Strategy of Export Firms From Developing Countries: An Exploratory Study of the Strategy Tripod. Bus. Soc. 2015, 54, 723–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlaghi, E.A.; Mostafavi, M. Studying the Effect of Social Responsibility of SMEs on Export Performance by Considering the Intermediate Role of Competitive Advantage and Organizational Reputation. QUID 2017, 1, 392–406. [Google Scholar]

- Theoharakis, V.; Bicakcioglu, N.; Tanyeri, M. Green Business Strategy and Export Performance: An Examination of Boundary Conditions from an Emerging Economy. Int. Market. Rev. 2019, 1, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Identidad, imagen y reputación de la empresa: Integración de propuestas teóricas para una gestión exitosa. Cuad. Gestión 2014, 14, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Griffin, J.J. Corporate Reputation and External Affairs Management. Part VII: Managing Reputation: Pursuing Everyday Excellence. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1997, 1, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.D.; Deephouse, D.L.; Ferguson, W.L. Do strategic groups differ in reputation? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcese, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Alfaro, J. Manual de la Empresa Responsable y Sostenible. Conceptos, ejemplos y herramientas de la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa o de la Empresa; McGraw Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.J.; Pavelin, S. Corporate Reputation and Social Performance: The Importance of Fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eryani, O.; Jönsson, G.; Mchugh, J. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Using Stakeholder Engagement to Improve Organizational Performance; Jönköping International Business School: Jönköping, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a Name? Reputation Building and Corporate Strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, S.; Rahman, N.; Post, C. The Impact of Board Diversity and Gender Composition on Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, D.; Morgan, J. CSR as Reputation Insurance: Primum Non Nocere. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, E.; Bruno, J.M.; Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J. The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 28, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vishwanathan, P.; Van Oosterhout, H.J.; Heugens, P.P.M.A.R.; Duran, P.; Essen, M.; Van Essen, M. Strategic CSR: A Concept Building Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strong, K.C.; Ringer, R.C.; Taylor, S.A. The Rules of Stakeholder Satisfaction (Timeliness, Honesty, Empathy). J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 32, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J. A stakeholder theory approach to designing environmental marketing strategy. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 1995, 10, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.-H.; Yu, J.-E.; Choi, M.-G.; Shin, J.-I. The Effects of CSR on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in China: The Moderating Role of Corporate Image. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irshad, A.; Rahim, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction and customer loyalty, moderating effect of corporate image (evidence from Pakistan). City Univ. Res. J. 2017, 1, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Cao, M.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Effects of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction and organizational attractiveness: A signaling perspective. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.R.; Isabella, G.; Boaventura, J.M.G.; Mazzon, J.A. The influence of corporate social responsibility on employee satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onkila, T. Pride or Embarrassment? Employees’ Emotions and Corporate Social Responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yin, H.; Liu, J.; Lai, K. How is Employee Perception of Organizational Efforts in Corporate Social Responsibility Related to Their Satisfaction and Loyalty Towards Developing Harmonious Society in Chinese Enterprises? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappel, C. An Employee Perspective: E Impact of CSR Perception on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Identification. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.; Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, S.; Bögel, P.M.; Adam, U. Employees’ perceived benefits from participating in CSR activities and implications for increasing employees engagement in CSR. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 24, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.K. The impact of corporate social responsibility on employee’s job satisfaction. J. Process. Manag. 2018, 6, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, H.; Jones, N. Sustainable supply chain management across the UK private sector. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurro, C.; Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Shaping Sustainable Value Chains: Network Determinants of Supply Chain Governance Models. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjong, R.; Wentworth, B.H. Expert judgment and risk perception. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, Stavanger, Norway, 17–22 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, T.D.; Michie, J.; Patterson, M.; Wood, S.J.; Sheehan, M.; Clegg, C.W.; West, M. On the validity of subjective measures of company performance. Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Robinson, R.B. Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, D.; Yaprak, A.; Cavusgil, S.T. Alliance Orientation: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Impact on Market Performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calantone, R.J.; Cavusgil, S.T.; Zhao, Y. Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaoming, Z.; Taylor, C.R.; Osland, G.E. The EXPERF Scale: A Cross-National Generalized Export Performance Measure. J. Int. Mark. 1998, 6, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lages, L.F.; Jap, S.D.; Griffith, D.A. The role of past performance in export ventures: A short-term reactive approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahimbisibwe, G.M.; Nkundabanyanga, S.K.; Nkurunziza, G.; Nyamuyonjo, D. Knowledge absorptive capacity: Do all its dimensions matter for export performance of SMEs? World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 12, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Gruen, T. Antecedents and Consequences of Customer-Company Identification: Expanding the Role of Relationship Marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Salinas, E.; Pina-Pérez, J. Modeling the brand extensions’ influence on brand image. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 62, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E.; Rohrbaugh, J. A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, N.; Stern, L.W.; Achrol, R.S. Assessing Reseller Performance from the Perspective of the Supplier. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the Involvement Construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet, J.-F. Consumer Racism and Its Effects on Domestic Cross-Ethnic Product Purchase: An Empirical Test in the United States, Canada, and France. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Benet-Martínez, V.; Garolera, J. Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: A study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Herrera, J. El papel de la agricultura intensiva en la economía de la provincia de almería. Rev. Humanid. Cienc. Soc. 2004, 19, 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, F.J.; García, R.; Molina, J. Claves para la interpretación del modelo económico almeriense basado en la agricultura del alto rendimiento. Meditterráneo Económico 2002, 2, 283–311. [Google Scholar]

- Galdeano-Gómez, E.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Pérez-Mesa, J.C. Sustainability dimensions related to agricultural-based development: The experience of 50 years of intensive farming in Almería (Spain). Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2013, 11, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdeano-Gómez, E.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Pérez-Mesa, J.C.; Piedra-Muñoz, L. Exploring Synergies Among Agricultural Sustainability Dimensions: An Empirical Study on Farming System in Almería (southeast Spain). Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Reigada, A.; Neira, D.P.; Soler, M. Evolución histórica y sostenibilidad social, económica y ecológica de la agricultura almeriense. In Proceedings of the Old and New Worlds: The Global Challenges of Rural History International Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 27–30 January 2016; Available online: https://lisbon2016rh.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/onw-0097.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Aznar- Sánchez, J.Á. El proceso de internacionalización comercial de la horticultura intensiva almeriense. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época 2007, 1, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: Personal computer adoption ans use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Laurence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.B. How Many Subjects Does It Take To Do A Regression Analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1991, 26, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C. The use of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. J. Acc. Lit. 2016, 37, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Correlation Problems Referring to One Correlation Comparison of a correlation with a constant 0 (bivariate normal model) Comparison of a correlation with 0 (point biserial model) Comparison of a correlation with a constant 0 (tetrachoric correlation model). Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 4, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index Construction with Formative Indicators: An Alternative to Scale Development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Bagozzi, R.P. Psychological Methods On the Nature and Direction of Relationships Between Constructs and Measures. Psychol. Methods 2000, 5, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Jarvis, C.B.; MacKenzie, S.B. A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. FAQ—Partial Least Squares and PLSGraf. 2000. Available online: http://disc-nt.cba.uh.edu/chin/plsfaq.htm (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- Moutinho, L.; Huarng, K.-H. Quantitative Modelling in Marketing and Management. In Quantitative Modelling in Marketing and Management; World Scientific: Singapore, 2012; pp. 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Werts, C.; Linn, R.; Jöreskog, K. Intraclass Reliability Estimates: Testing Structural Assumptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, K.; Peacock, E.; Chin, W.W. Extending the technology acceptance model: The influence of perceived user resources. ACM SIGMIS 2001, 32, 86–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.; Zeller, R. Reliability and Validity Assessment; Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences 07-017; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Srivastava, S.C.; Jiang, L. Trust and Electronic Government Success: An Empirical Study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Estrada, J.M.V.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. The Predictive Sample Reuse Method with Applications. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1975, 70, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling 1. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. Advanced PLS-SEM Topics: PLS Multigroup Analysis; Working Paper; University of Seville: Seville, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, A.M.; Anderson, E.; Maclnnis, D.J. Reputation Management as a Motivation for Sales Structure Decisions. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ping, R.A., Jr. The effects of satisfaction and structural constraints on retailer exiting, voice, loyalty, opportunism, and neglect. J. Retail. 1993, 69, 320–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Farmers | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 2. Clients | 0.667 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 3. Competitors | 0.559 | 0.548 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 4. Community | 0.399 | 0.392 | 0.328 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 5. Employees | 0.570 | 0.559 | 0.468 | 0.334 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 6. Environment | 0.612 | 0.600 | 0.503 | 0.359 | 0.513 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 7. Partners | 0.552 | 0.541 | 0.453 | 0.324 | 0.462 | 0.496 | 1.000 | |||||

| 8. EXP | 0.082 | 0.224 | −0.03 | 0.231 | −0.02 | 0.137 | −0.08 | 1.000 | ||||

| 9. FP | 0.030 | 0.230 | 0.018 | 0.072 | 0.154 | 0.110 | 0.106 | 0.598 | 1.000 | |||

| 10. IR | −0.08 | −0.49 | 0.156 | 0.187 | 0.184 | 0.164 | 0.011 | 0.485 | 0.615 | 1.000 | ||

| 11. CSR | 0.825 | 0.809 | 0.678 | 0.484 | 0.691 | 0.742 | 0.669 | 0.392 | 0.531 | 0.789 | 1.000 | |

| 12. SS | 0.185 | 0.203 | 0.090 | 0.204 | 0.223 | 0.144 | 0.020 | 0.359 | 0.479 | 0.784 | 0.746 | 1.000 |

| Number items | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 34 | 3 |

| Mean1 | 6.16 | 6.15 | 5.60 | 5.63 | 5.68 | 5.12 | 6.14 | 5.29 | 5.28 | 5.70 | 5.78 | 5.67 |

| Standard deviation | 1.37 | 1.21 | 1.52 | 1.52 | 1.32 | 1.75 | 1.05 | 1.40 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.39 | 0.81 |

| Variables and Items | Weight (p-Value) | (t-Value) | Load (p-Value) | (t-Value) | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Employees | |||||

| (Emp1) Our company has established flexible policies to provide a good work-life balance for its employees. | 0.030 | (0.14) | 0.553 *** | (4.20) | |

| (Emp2) Our company has established training and personal development programs for employees. | 0.404 * | (2.39) | 0.760 *** | (7.73) | |

| (Emp3) In general, our company promotes positive discrimination programs in favor of women and people with disabilities. | 0.485 *** | (3.79) | 0.661 *** | (6.88) | |

| (Emp4) Our company promotes stable employment and recognizes its importance for both employees and society. | −0.216 | (0.92) | 0.451 * | (2.54) | N/A |

| (Emp5) Our company has a communication channel with its employees and is receptive to their proposals and complaints. | 0.161 | (0.83) | 0.488 *** | (3.39) | |

| (Emp6) Our company periodically evaluates the work environment and employee satisfaction. | 0.257 | (1.38) | 0.596 *** | (4.82) | |

| (Emp7) Our company has internal policies that prevent discrimination against ethnic minorities. | 0.373 * | (2.04) | 0.595 *** | (4.12) | |

| (b) Partners | |||||

| (Part1) Our company always tries to obtain the maximum profit from its activities. | 0.460 ** | (2.98) | 0.623 *** | (4.92) | |

| (Part2) Our company provides its partners / shareholders with clear, complete, and accurate information on its policies, decisions, and activities. | 0.161 | (0.72) | 0.697 *** | (5.88) | N/A |

| (Part3) Our company has an adequate communication channel with its partners / shareholders and is receptive to their proposals. | 0.679 ** | (3.09) | 0.885 *** | (10.12) | |

| (c) Clients | |||||

| (Cli1) Our company has extensive capacity to supply its customers throughout the year. | 0.231 | (1.84) | 0.674 *** | (7.10) | |

| (Cli2) Our company has a wide range of products, standardized in terms of quality and prices. | 0.195 | (1.58) | 0.741 *** | (7.85) | |

| (Cli3) Our company conducts studies on customer satisfaction. | 0.108 | (0.89) | 0.570 *** | (4.58) | N/A |

| (Cli4) Our company provides complete and accurate information about its products to its customers. | -0.041 | (0.32) | 0.586 *** | (6.02) | |

| (Cli5) Our company establishes control procedures to ensure compliance with customers. | 0.562 *** | (4.40) | 0.923 *** | (18.53) | |

| (Cli6) Our company responds to customer complaints. | 0.184 | (1.25) | 0.780 *** | (10.98) | |

| (d) Farmers | |||||

| (Agr1) Our company contributes to the growth of farmers / producers and to the continued profitability of their farms. | 0.063 | (0.25) | 0.732 *** | (6.79) | |

| (Agr2) Our company has procedures to control the working conditions and the hiring policy of its suppliers. | 0.389 * | (2.56) | 0.701 *** | (5.99) | |

| (Agr3) Our company has a communication channel with its farmers / producers and is receptive to their proposals and complaints. | 0.288 | (1.85) | 0.657 *** | (5.42) | N/A |

| (Agr4) Our company cooperates with its farmers / producers, providing technical advice for the improvement of their products. | 0.118 | (0.53) | 0.632 *** | (5.07) | |

| (Agr5) Our company promotes organic and / or integrated production among its farmers / producers. | 0.217 | (1.21) | 0.625 *** | (3.94) | |

| (Agr6) Our company considers it essential that its farmers / producers have the appropriate good agricultural practices, food safety, and environmental certifications. | 0.375 * | (2.49) | 0.751 *** | (7.07) | |

| (e) Environment | |||||

| (Env1) Our company properly manages waste. | −0.226 | (1.14) | 0.244 | (1.41) | |

| (Env2) Our company has an energy saving program. | 0.403 | (1.89) | 0.754 *** | (7.61) | |

| (Env3) Our company adopts programs for the use of alternative energy. | −0.158 | (0.79) | 0.594 *** | (5.20) | |

| (Env4) Our company has implemented a program to reduce water consumption. | 0.408 * | (2.22) | 0.837 *** | (10.32) | N/A |

| (Env5) Our company periodically conducts environmental audits. | 0.294 | (1.80) | 0.690 *** | (6.24) | |

| (Env6) Our company promotes an efficient use of inputs (water, fertilizers, and phytosanitary products), as well as adequate treatment of agricultural waste among its farmers / producers. | 0.386 * | (2.22) | 0.779 *** | (7.25) | |

| (f) Community | |||||

| (Com1) Our company gives priority to hiring employees in our municipality or region. | −0.598 * | (2.55) | 0.114 | (0.69) | |

| (Com2) Our company gives priority to hiring suppliers in our region. | 0.754 *** | (3.21) | 0.606 *** | (4.06) | N/A |

| (Com3) Our company dedicates part of its budget to charitable donations and actively sponsors or finances social events (sports, music, etc.) | 0.756 *** | (4.97) | 0.809 *** | (6.23) | |

| (g) Competitors | |||||

| (Comp1) Our company promotes free competition among companies in its sector. | 0.462 * | (2.50) | 0.721 *** | (5.26) | |

| (Comp2) Our company promotes cooperation (alliances, associations) with companies in its sector for commercial purposes. | 0.247 | (0.99) | 0.797 *** | (6.94) | N/A |

| (Comp3) Our company carries out cooperation initiatives (alliances, associations) for innovation purposes. | 0.545 * | 0.545 * | 0.860 *** | (9.02) | |

| (h) Financial Performance | |||||

| (FP1) Sales have increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.891 *** | (27.32) | |

| (FP2) Market share has increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.861 *** | (19.41) | CA= 0.853 CR= 0.901 |

| (FP3) Profitability has increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.804 *** | (20.16) | AVE=0.696 |

| (FP4) Productivity has increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.776 *** | (6.60) | |

| (i) Export Performance | |||||

| (ExP1) In recent years, our export sales have increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.915 *** | (19.63) | |

| (ExP2) The percentage of exports of the company’s total sales has grown in recent years. | N/A | N/A | 0.915 *** | (19.43) | CA = 0.942 CR =0.958, |

| (ExP3) We have expanded our operations in profitable foreign markets. | N/A | N/A | 0.927 *** | (40.19) | AVE=0.851 |

| (ExP4) We are satisfied with the rate of expansion in the new markets. | N/A | N/A | 0.933 *** | (49.30) | |

| (j) Image and Reputation | |||||

| (ImR1) Our company is a dynamic company. | N/A | N/A | 0.871 *** | (38.20) | |

| (ImR2) Our company is an innovative company. | N/A | N/A | 0.824 *** | (25.96) | |

| (ImR3) Our company is a company with high quality standards. | N/A | N/A | 0.822 *** | (23.10) | CA=0.936 CR=0.948 |

| (ImR4) Our company is an efficient company. | N/A | N/A | 0.809 *** | (16.73) | AVE=0.723 |

| (ImR5) Our company is a recognized company. | N/A | N/A | 0.864 *** | (33.57) | |

| (ImR6) Our company is an admired company. | N/A | N/A | 0.846 *** | (33.62) | |

| (ImR7) Our company is a prestigious company. | N/A | N/A | 0.911 *** | (51.20) | |

| (a) Stakeholder Satisfaction | |||||

| (SS1) The overall satisfaction of our customers with our company has increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.892 *** | (36.41) | CA=0.883 CR=0.928 |

| (SS2) The overall satisfaction of our farmers/suppliers with our company has increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.928 *** | (57.28) | AVE=0.810 |

| (SS3) The satisfaction and motivation of our employees has increased. | N/A | N/A | 0.880 *** | (39.83) |

| Export Performance | Financial Performance | Image and Reputation | Stakeholder Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export Performance | 0.922 | 0.671 | 0.512 | 0.394 |

| Financial Performance | 0.596 | 0.834 | 0.688 | 0.555 |

| Image and Reputation | 0.482 | 0.614 | 0.850 | 0.862 |

| Stakeholder Satisfaction | 0.361 | 0.481 | 0.783 | 0.900 |

| R2 | Q2 | Predictive Q2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Export Performance | 0.153 | 0.120 | −0.106 |

| Financial Performance | 0.282 | 0.180 | 0.183 |

| Image and Reputation | 0.623 | 0.413 | 0.621 |

| Stakeholder Satisfaction | 0.556 | 0.425 | 0.570 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martos-Pedrero, A.; Cortés-García, F.J.; Jiménez-Castillo, D. The Relationship between Social Responsibility and Business Performance: An Analysis of the Agri-Food Sector of Southeast Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226390

Martos-Pedrero A, Cortés-García FJ, Jiménez-Castillo D. The Relationship between Social Responsibility and Business Performance: An Analysis of the Agri-Food Sector of Southeast Spain. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226390

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartos-Pedrero, Antonio, Francisco Joaquín Cortés-García, and David Jiménez-Castillo. 2019. "The Relationship between Social Responsibility and Business Performance: An Analysis of the Agri-Food Sector of Southeast Spain" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226390