2.1. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

OCB typically refers to behaviors that positively impact the organization or its members. The concept of OCB regards employee behaviors that are not part of an individual job description, are not included in an employee contract, and are beneficial to organizational performance [

2,

3]. OCBs are voluntary behaviors of organization members; they go beyond the scope of their job responsibilities, and are aimed at assisting co-workers and/or taking care of the organization and its operations. S.P. Robbins claims that OCBs are staff behaviors that are not part of their required work, but support the effective functioning of the organization [

19]. Podsakoff et al. define organizational citizenship behaviors as behaviors that do not appear in the formal job description, but facilitate the performance of tasks in the organization [

20].

Such behaviors include: helping a new employee to catch up, helping a co-worker to deal with work overload, staying at work after hours, taking on additional responsibilities, tolerating temporary impositions without complaint, defending an organization, openly speaking about issues of importance to the organization, etc. [

5,

21].

As highlighted in the literature, OCB may be directed towards the organization (e.g., carrying out role requirements well beyond minimum required levels) and/or towards individual co-workers (e.g., helping a particular other person with a relevant task) and may contribute only indirectly to the organization [

5,

6,

22].

Several studies in the organizational literature highlight the benefits of OCBs. Among others, it has been found that employee engagement in OCBs may increase knowledge sharing and job performance [

23,

24]. Other authors claim that OCBs exhibited by workers enhance team and group cohesiveness and contribute to overall organizational performance [

2,

23,

25,

26,

27]. At the same time, OCB does not mean working long hours and taking on extra assignments with no thought of reward. Rather, it means that, through this type of behavior, employees provide the organization with many creative solutions to problems and provide suggestions to facilitate the implementation of strategies [

28].

Initially, researchers described various OCBs in terms of two factors: altruism and serving principles. Altruism defined behaviors aimed at helping other colleagues, while the other factor was related to maintaining rules and norms for cooperation and supporting team spirit. Over time, many researchers began to add in more groups of voluntary behaviors that go beyond formal responsibilities while affecting organizational effectiveness.

As a result, Podsakoff and his colleagues attempted to systematize the subject literature. Based on a review of previous publications, they identified almost 30 theoretical constructs to describe activities that can be classified as various forms of OCB. Nevertheless, these behaviors overlapped in many ways. Their comparison helped distinguish seven main categories of citizenship behaviors: helping behavior (including altruism and courtesy), sportsmanship, organizational loyalty, organizational compliance, individual initiative, civic virtue, and self-development [

20].

In their conceptual framework Podsakoff et al. claim that helping behavior refers to voluntarily helping others with, or preventing the occurrence of, work-related problems [

20]. The first part of the above definition refers to helping others with work-related problems. This includes several elements highlighted by different researchers, such as altruism or peace-making [

1,

29,

30]. Altruism is directly intended to help a specific person in face-to-face situations (e.g., helping others who have been absent, volunteering for things that are not required, orienting new people even though it is not required, helping others who have heavy workloads). Peace-making refers to behaviors aimed at preventing or solving conflicts and cheerleading [

1,

31].

The second OCB dimension is sportsmanship. This dimension is explained as a citizen-like posture of uncomplainingly tolerating the inevitable inconveniences and impositions of work [

1,

20].

The third dimension of OCBs is organizational loyalty. Organizational loyalty entails promoting the organization to outsiders, protecting and defending it against external threats, and remaining committed to it even under adverse conditions [

20,

32]. The next dimension, organizational compliance, refers to internalization and employee’s acceptance of and strict adherence to organizational procedures and policies. In more practical terms it means that an employee obeys organizational norms even if nobody can see it [

4,

20].

Individual initiative, the next OCB dimension refers to going well beyond minimally required levels of effort. Such behaviors include voluntary acts of creativity and innovation designed to improve one’s task or the organization’s performance, persisting with extra enthusiasm and effort to accomplish one’s job, volunteering to take on extra responsibilities, and encouraging others in the organization to do the same. Examples of such behavior are proposing improvements to the organization, voluntarily engaging in additional responsibilities, punctuality, and housekeeping. [

1,

4,

20,

32].

The next dimension of OCBs proposed by Podsakoff et al. is civic virtue [

20]. This concerns an employee’s willingness to participate in the governance process and to take responsibility for the whole organization. In practice, civic virtue includes responsible, constructive involvement in the political process of the organization, attending the organization’s meetings, voluntarily monitoring the organizational environment to identify potential threats and opportunities, and voluntary acts of creativity and innovation in organizations. [

4,

20,

29,

33].

The last of the seven OCB dimensions proposed by Podsakoff et al. is self-development. This dimension includes voluntary behaviors that employees engage in to improve their knowledge, skills, and abilities to then be able to better contribute to the organization [

6,

20,

33].

In addition to the above-mentioned division of OCB into seven categories, the literature also proposes the typology of Williams and Anderson, who divide these behaviors into those that are people-oriented (OCB-P) and organization-oriented (OCB-O). OCB-P is understood as behaviors that by helping a particular person (e.g., showing compassion toward colleagues experiencing personal problems) contribute to the more effective operation of the company. They are therefore closely related to altruism. OCB-O, in turn, refers to the activities of an employee that support the organization as a whole. They are manifested, for example, in compliance with formal and informal rules in force in the company, which help avoid problems in its functioning [

34]. As Spitzmuller claims, the dividing OCBs according to the target of the behavior is extremely important for researchers and theorists because of the distinctness of the nomological networks of the two forms of OCB [

35].

Yet another classification is proposed by Van Dyne, Cummings, and Parks, who distinguish between affiliation-oriented (AOCB) and challenge-oriented citizenship behavior (COCB). The former is focused on permanent support by maintaining the existing relationships and processes in the organization. The latter is related to actions leading to changes in the organization by improving current relationships and processes [

36].

The specifics of how an organization works, co-worker relations, forms and levels of employee remuneration and many other factors can influence what kind of organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB-P and OCB-O) employees manifest. Based on the review of the subject literature and due to the differences in how the surveyed organizations function, I postulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. The frequency at which organizational citizenship behaviors manifest is similar in the public and private sectors.

Hypothesis 2. Public-sector employees manifest more people-oriented than organization-oriented citizenship behaviors.

2.1.1. OCB: Effects

Regardless of the variety of definitions and classifications of organizational citizenship behaviors, all researchers agree that they are a heterogeneous construct and consist of many dimensions covering different categories of behavior. The concept of OCB is derived from the premises of the theory of interpersonal relations, in which the organization is treated as ‘a kind of social system—a form of social organization in which certain informal norms and rules of coexistence apply. They exist outside official procedures, creating communities governed by specific, developed values, distinguished by established principles of cooperation, atmosphere, etc.’ [

37] (p. 31). Therefore, organizational citizenship behaviors falling into this category serve as an example of a positive system that favors the development of an organization. Despite the fact that OCBs are by definition voluntary, uncontrolled behavior, their consequences are visible in the results of the organization’s operation. OCBs can also affect the effectiveness of an organization by:

- -

reducing disparities in the level of tasks performed and results achieved [

26];

- -

increasing the productivity of colleagues and superiors [

38,

39];

- -

freeing up resources for more productive purposes [

3];

- -

enhancing the organization’s ability to attract and retain the best employees [

1,

40].

At this point the ever-strengthening relationship between OCB and corporate social responsibility (CSR) also needs to be emphasized. CSR can be defined as “the strategies and actions that primarily deal with organizations’ or firms’ voluntary relationships with their community and societal stakeholders” [

41]. Until recently, researchers into CSR had mainly focused on external stakeholders, such as investors and customers [

42,

43]. Now, attention has shifted decidedly onto employees [

12,

44,

45]. Employees are one of the most important stakeholders in any organization. Since they both affect and are affected by organizational activities, employees play a key role in the success or failure of their organization.

Global empirical research has confirmed the significant positive impact of CSR on employee attitudes and behavior [

46,

47]. This relationship is also inverse. Researchers are increasingly focusing on individual-level CSR perspectives, suggesting that employee attitudes and behavior play a key role in transforming CSR into beneficial organizational outcomes. When an organization begins doing various types of activity for the welfare of its employees, employees also respond by demonstrating better citizenship behaviors in the workplace and a positive attitude towards their organization. According to Social Exchange Theory, when an employee develops a psychological relationship with the organization, he engages more in his professional and organizational role. Saks [

48] noted a significant positive relationship between employee engagement and job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior, as well as a significant negative relationship with intention to quit. An organization implementing CSR can increase employees’ sense of their own importance at work; employees feel that they are part of an organization that is serving the community to make the world a better place. Albdour and Altarawneh [

49] observed a significant positive relationship between employees’ perception of an internally focused CSR and their organizational commitment.

For this reason, CSR should be treated as a long-term investment that supports sustainable company development [

50]. Furthermore, companies with better social performance are more likely to have positive earnings [

51]. Organizations should therefore take actions that support employees’ engagement and their exhibiting of OCBs, as well as motivating their CEO to take risks with regard to CSR. The author may tackle these relationships as the subject of another future study.

Due to the impact of citizenship behaviors on the effectiveness of organizations that has already been confirmed by numerous studies, they are interested in making this phenomenon universal and frequent. For the organization, not only the frequency, but also the intensity of these behaviors (the degree of employee involvement in OCB and the type of behavior) matters.

2.1.2. OCB: Antecedents

Many antecedents have been studied in relation to OCB. Many researchers point to the following four key categories of OCB antecedent: individual (employee) characteristics, task characteristics, organizational characteristics, and leadership behaviors [

20,

52]. Previous studies have shown that OCB is strongly correlated with job attitudes, task variables, and leadership behaviors. In the first category, job satisfaction, perception of fairness and organizational commitment in particular make employees want to engage in citizenship behavior. When considering the features of tasks, researchers unanimously emphasize their strong relationship with the manifestation of OCB. It is important that the task be intrinsically satisfying and accompanied by feedback. The most important leadership behaviors from the OCB point of view are supportive leader behaviors, transformational leadership, and the leader–follower exchange [

31].

In this research, the author wanted to confirm the previously examined relationship between organizational involvement and OCB, but taking into account the aspect of two different types of organizations I assume that:

Hypothesis 3. There is a positive relationship between the attitude of organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors of employees in both public and private institutions.

Due to the subject matter of the article, organizational commitment will be described from here on with particular emphasis on its impact on manifesting organizational citizenship behaviors.

2.2. Organizational Commitment and OCB

Organizational commitment (OC) is defined as ‘the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization’ [

53] (p. 226). Colloquially, it can be considered that commitment is the same as the employee’s membership of the organization. Organizational commitment exemplifies an employee’s relationship with the organization. It is a ‘mental state which has repercussion on the employee’s choice whether to or not to maintain his membership in the organization’ [

54] (p. 26). To feel greater organizational commitment, employees must accept and sincerely believe in the company’s values, make efforts to serve it, and enjoy being a member of it [

55].

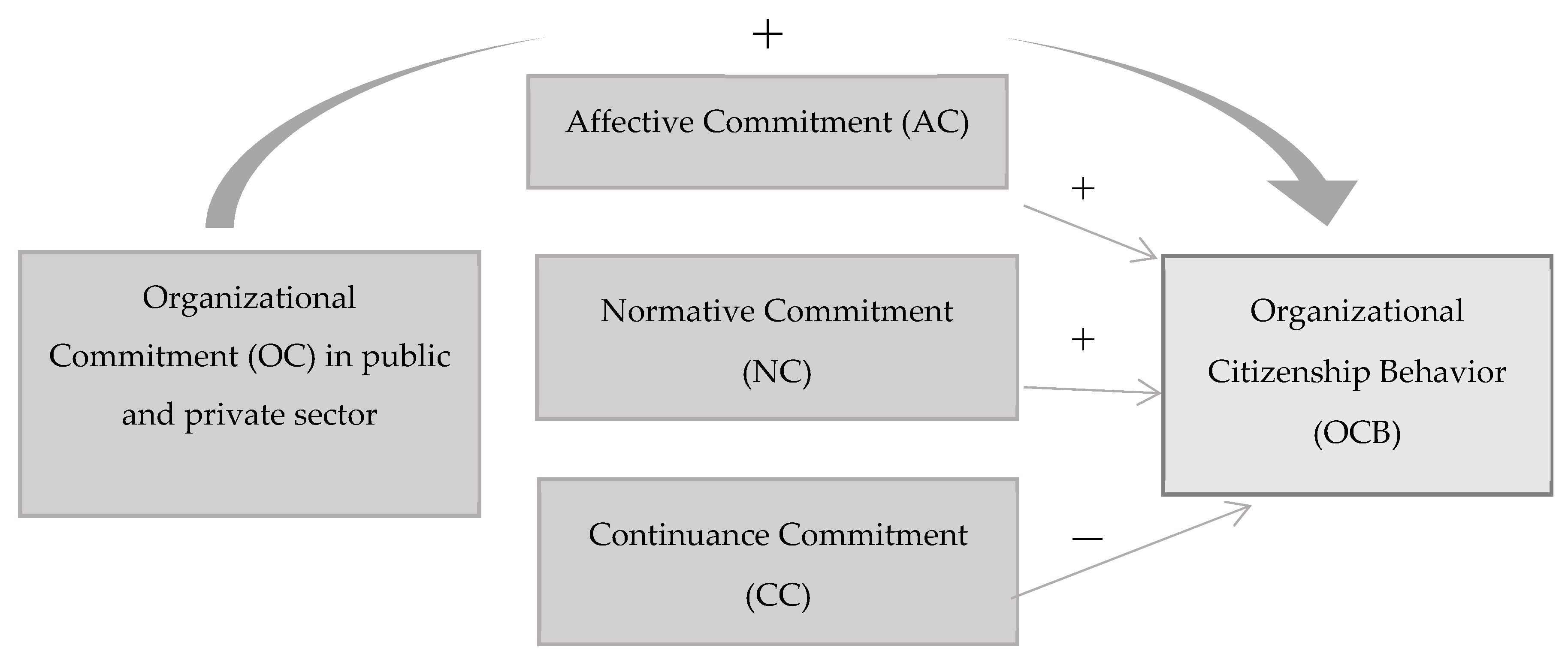

One of the most popular models of commitment to the organization is the Meyer and Allen model [

13]. These authors treat organizational commitment as employee identification with the organization. Accordingly, Allen and Meyer theorize that organizational commitment encompasses three dimensions: affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment [

13].

In its affective sense, commitment means the employee’s emotional attachment to the organization, which reflects the degree to which the individual wants to be part of the organization. The employee wants to be identified with the organization and also to get involved in its affairs. Persons with strong affective commitment work in the organization of their own free will, not by coercion [

56]. The affective dimension is closely linked to the positive feelings associated with the place of employment (a sense that work allows them to meet needs and goals, satisfaction, and a feeling of support from superiors and the entire organization) [

57]. Affective commitment (AC) is determined by ‘an employee’s personal choice to remain committed to the organization via some emotional identification with the organization’ [

58] (p. 86). Affective commitment is a positive attitude toward the organization [

59]. Mahal [

60] additionally points out that the employee’s attitude as an individual is related to personal values which that person brings to the organization. As M. Łaguna, E. Mielniczuk, and E. Wuszt claim, ‘people with strong affective commitment work more and achieve better results than those who do not display this type of attachment’ [

61] (p. 50). The Meyer and Allen model illustrates that affective commitment can be influenced by several factors such as direct clarity of goals and a degree of manageable difficulty in reaching goals, job challenges, management receptiveness to feedback, role clarity provided by the organization, peer cohesion, equity of opportunity and compensation, perceived personal importance, and timely and constructive feedback [

13].

Continuance commitment (CC) is associated with cost calculation in the event of leaving the organization [

13]. An employee who exhibits this dimension of commitment remains in the organization, because he/she perceives it as a kind of compulsion, and believes that he/she must do so. It develops when the costs of leaving are too high, when an employee has made too much investment in a given organization or when he/she does not see any alternative employment [

57]. Continuance commitment can be regarded as a contractual attachment to the organization [

62]. The person’s attachment to the organization in this dimension is constantly based on the assessment of the economic benefits obtained by staying in it [

63]. An employee who displays continuance commitment performs his/her duties worse and has more difficult relationships with colleagues.

The third and last dimension of organizational commitment proposed by Meyer and Allen is normative commitment (NC). It is associated with a sense of moral obligation to remain in the organization. At the core of manifestation of normative commitment are socialization experiences gained at first in the family and later in the workplace, especially if the importance of loyalty to one organization was emphasized [

13]. The NC level may be influenced by the rules an individual accepts and the reciprocal relationship between an organization and its employees [

64].

Researchers into organizational commitment very often determine the dependence between its individual dimensions and the organizational behavior an employee displays. Empirically confirmed research indicates that employees with highly developed affective commitment are more valuable to organizations than those with lower levels. Similar but weaker effects are observed when normative commitment is manifested. The worst results are observed in the case of employees with strong continuance commitment. Numerous studies also indicate that there are negative correlations between organizational commitment and the tendency to leave the organization and staff turnover. This relationship is strongest in affective commitment, but it applies to all of the three dimensions [

65,

66]. Mathieu and Zajac [

67] also recognized the dependence between organizational commitment and employee absenteeism. It is characteristic of the affective dimension, but it does not occur in the case of continuance commitment. Affective commitment has also been the most consistent and strongest predictor of positive organizational outcomes, such as work effort and performance [

59,

68].

The subject literature clearly indicates the correlations between organizational commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior (this is discussed in the ‘OCB: antecedents’ section). Studies confirm that this affective nature of organizational commitment is most correlated with OCB [

20] but it is important to ‘take into account the other forms of commitment that can be present at the same time for the same individual’ [

52] (p. 53).

Based on previous related empirical findings, I postulate the following hypotheses:

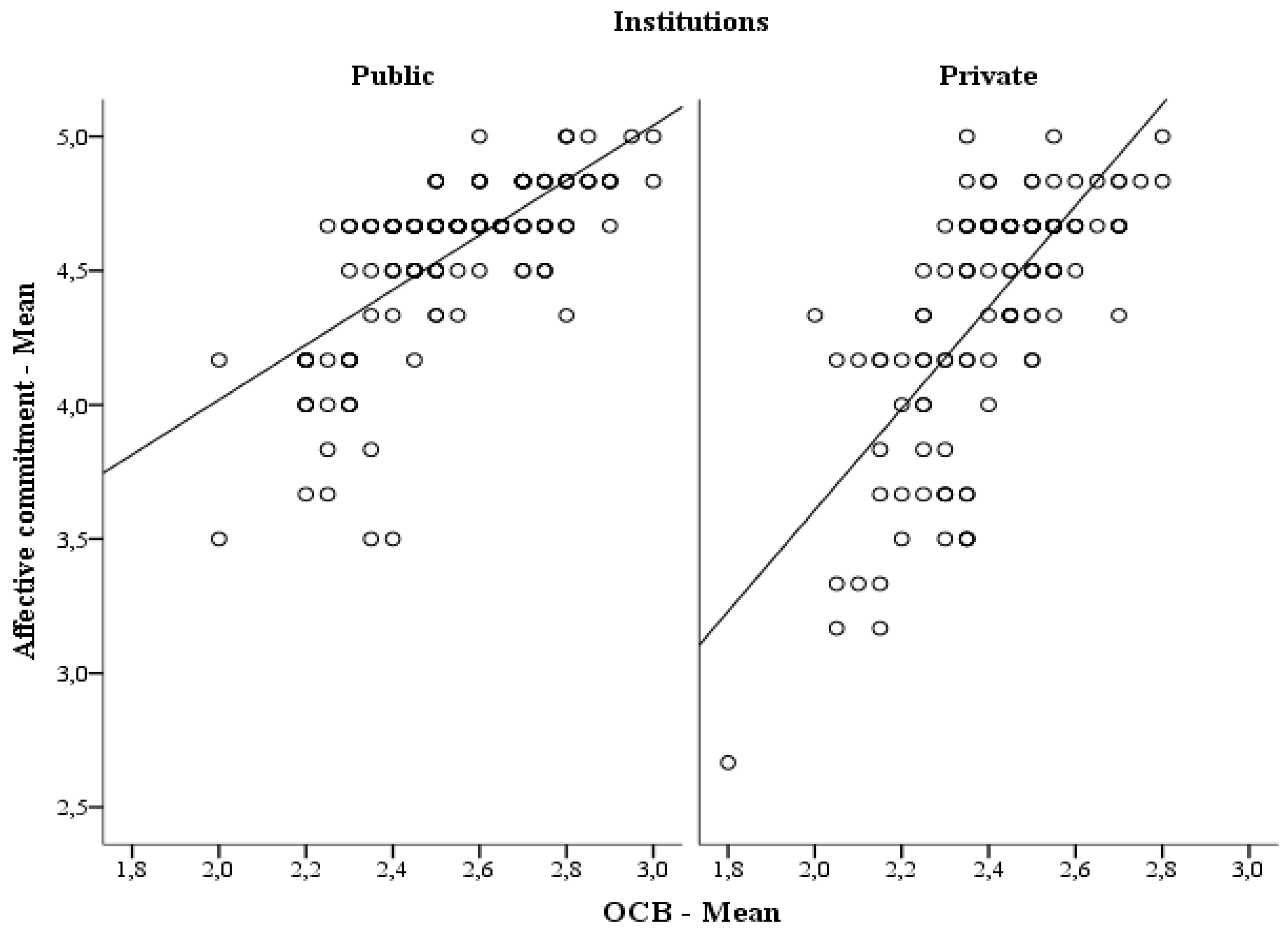

Hypothesis 4. The dimension most positively correlated with OCB is the affective dimension of organizational commitment of employees both in public and private institutions.

Hypothesis 5. Continuance commitment is uncorrelated with OCB in both types of organizations.

The purpose of this publication is to identify and assess the level of correlation between the various dimensions of organizational commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in public and private organizations in Poland. The author first presents the frequency of OCB manifested by employees of individual institutions, and then seeks to find whether there are differences in the level of organizational commitment of these employees taking into account their workplace. Then, the correlations between CC and OCB will be presented.