Short-Term and Long-Term Entrepreneurial Intention Comparison between Pakistan and Vietnam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Temporal Construal Theory

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. Interrelation between TPB Dimensions (Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavior Control)

2.4. Integration of TCT and TPB

2.4.1. Attitude Mediation Effect

2.4.2. Perceived Behavior Control Mediation Effect

2.4.3. Short-Term Entrepreneurial Intention Mediation Effect

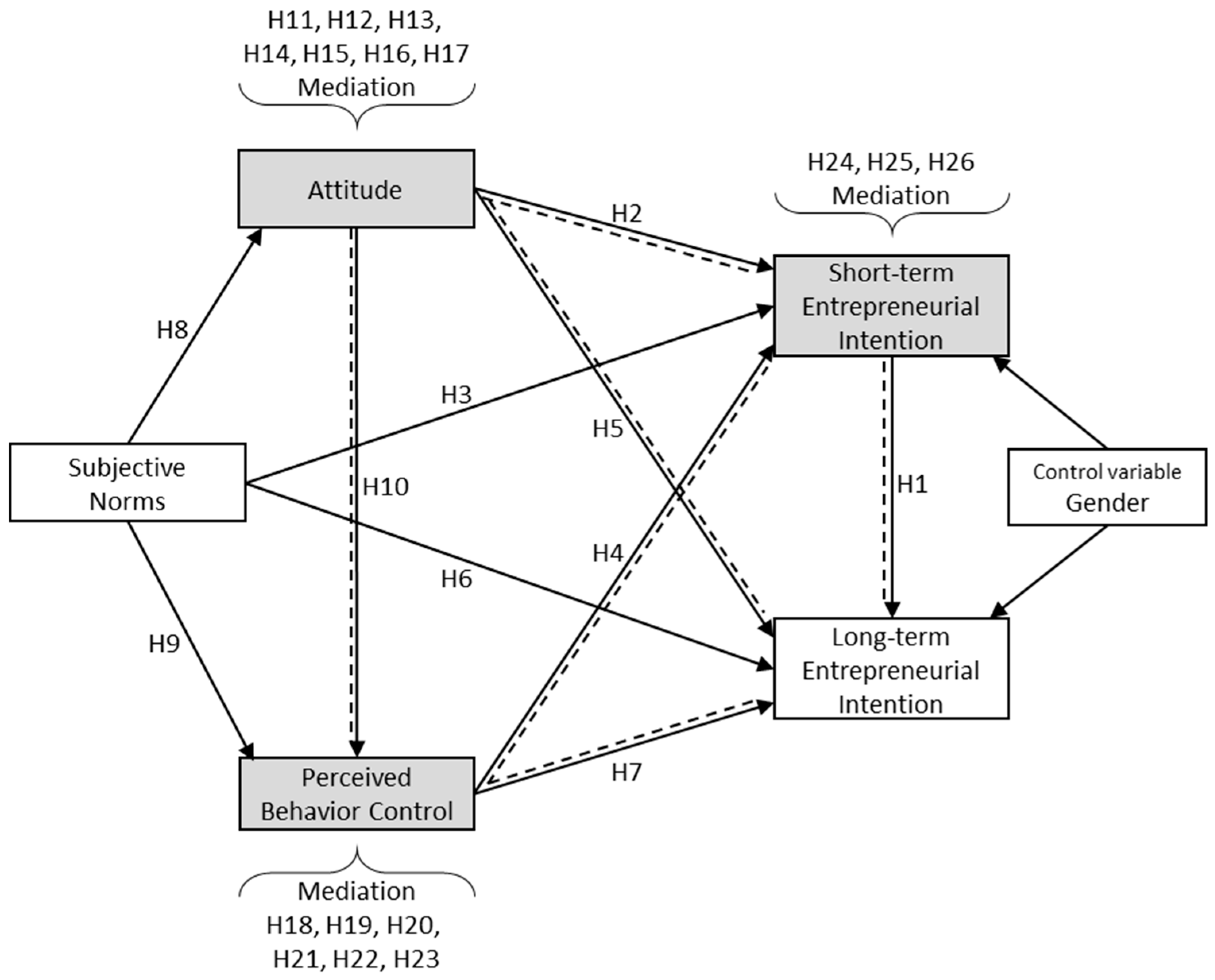

2.5. Study Framework

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures of Entrepreneurial Intention

3.3. Control Variable

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.4. Mediating Analysis

4.5. Multigroup Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical Contribution

7. Implications

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Attitudes towards objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychol. Rev. 1974, 81, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, C.; Zanella, G.; Dosamantes, C.A.D.; Cardenas, C. Measuring entrepreneurial intent? Temporal construal theory shows it depends on your timing. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 671–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F. The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1993, 18, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, T.; Sagristano, M.D.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N.; Chaiken, S. When values matter: Expressing values in behavioral intentions for the near vs. distant future. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Chin, W.W. A comparison of approaches for the analysis of interaction effects between latent variables using partial least squares path modeling. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2010, 17, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, A.; Kamarudin, S.; Rizal, A.M.; Omar, R. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior in Near and Distant Future. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on New Ideas in Management, Economics and Accounting, Paris, France, 2–4 November 2018; pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- ADB-Asian Development Bank. Kyrgyz Republic: Women’s Entrepreneurship Development Project; Financed by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction; Asian Development Bank: Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, H.; Jianfeng, C.; Ramzan, S. Personality traits and theory of planned behavior comparison of entrepreneurial intentions between an emerging economy and a developing country. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumasjan, A.; Welpe, I.; Spörrle, M. Easy Now, Desirable Later: The Moderating Role of Temporal Distance in Opportunity Evaluation and Exploitation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 37, 859–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Benitez-Amado, J. How information technology influences environmental performance: Empirical evidence from China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, M.; Singer, P.K.S.; Carmona, J.; Wright, F.; Coduras, A. 2016/2017 Global Report. GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; Babson College Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carsrud, A.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial Motivations: What Do We Still Need to Know? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovleva, T.; Kolvereid, L.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurial intentions in developing and developed countries. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N., Jr. Entrepreneurial Intentions are Dead: Long Live Entrepreneurial Intentions; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F. The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Keeley, R.H.; Klofsten, M.; Parker GG, C.; Hay, M. Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterp. Innov. Manag. Stud. 2001, 2, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.-W. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornikoski, E.; Maalaoui, A. Critical reflections–The Theory of Planned Behaviour: An interview with Icek Ajzen with implications for entrepreneurship research. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.S.; Ferreira, J.J.; Gomes, D.N.; Gouveia Rodrigues, R. Entrepreneurship education: How psychological, demographic and behavioural factors predict the entrepreneurial intention. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, G. Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 463–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Hermel, P.; Srivatava, A. Entrepreneurial intentions–theory and evidence from Asia, America, and Europe. J. Int. Entrep. 2017, 15, 324–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetakis, L.A.; Kafetsios, K.; Lerakis, M.; Moustakis, V. Investigating the role of self construal in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, M.S.; Budic, S. The Impact of Personal Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioural Control on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Women. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 9, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F. The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, M.Á.; Méndez, M.T. Entrepreneurship, economic growth, and innovation: Are feedback effects at work? J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marlino, D. Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, C.; Leffel, A.; Calvoz, R. Identification of Temporal Construal Effects on Entrepreneurial Employment Desirability in STEM Students. J. Entrep. 2015, 24, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, A.; Contreras, F.; Espinosa, J.C.; Barbosa, D. Entrepreneurial intentions of Colombian business students: Planned behaviour, leadership skills and social capital. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkley, W.W. Entrepreneurial behaviour: The role of values. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 290–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Temporal construal and time-dependent changes in preference. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.; Kenny, D. Statistical power and test of mediation, Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 122–139. [Google Scholar]

- Acs, Z.J.; Szerb, L.; Lloyd, A. Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018; Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W.B., Jr.; Chang-Schneider, C.; Larsen Mcclarty, K. Do people’s self-views matter? Self-concept and self-esteem in everyday life. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linan, F. Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2008, 4, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzion, U.; Rapoport, A.; Yagil, J. Discount rates inferred from decisions: An experimental study. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.; Rueda-Cantuche, J. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, J. A longitudinal study of the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Acad. Entrep. J. 2004, 10, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, D.; Singer, S.; Herrington, M. 2015/2016 Global Report. GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; Babson College, Universidad del Desarrollo, Universiti Tun Abdul Razak, Tecnológico de Monterrey; International Council for Small Business (ICSB): Wellesley, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNDP. Unleashing Ethiopia’s Entrepreneurial Spirit. 2016. Available online: http://www.et.undp.org/content/ethiopia/en/home/operations/projects/sustainableeconomicdevelopment/project_EDP.html (accessed on 10 November 2017).

- Gielnik, M.M.; Barabas SFrese, M.; Namatovu-Dawa, R.; Scholz, F.A.; Metzger, J.R.; Walter, T. A temporal analysis of how entrepreneurial goal intentions, positive fantasies, and action planning affect starting a new venture and when the effects wear off. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovallo, D.; Kahneman, D. Living with uncertainty: Attractiveness and resolution timing. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2000, 13, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Abelson, R.P. Psychological status of the script concept. Am. Psychol. 1981, 36, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, B.; Yennita. Understanding the entrepreneurial intention among international students in Turkey. J. Global Entrep. Res. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engle, R.L.; Dimitriadi, N.; Gavidia, J.V.; Schlaegel, C.; Delanoe, S.; Alvarado, I.; He, X.; Buame, S.; Wolff, B. Entrepreneurial intent: A twelve-country evaluation of Ajzen’s model of planned behavior. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Townsend, T.G.; Grange, C.; Belgrave, F.Z.; Wilson, K.D.; Fitzgerald, A.; Owens, K. Understanding HIV risk among African American adolescents: The role of Africentric values and ethnic identity in the theory of planned behavior. Humboldt J. Soc. Relat. 2006, 30, 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Urbano, D.; Guerrero, M. Regional variations in entrepreneurial cognitions: Start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Van Gelderen, M.; Tornikoski, E.T. Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behavior. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roy, R.; Akhtar, F.; Das, N. Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1013–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Shinnar, R.S.; Giacomin, O.; Janssen, F. Entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions: The role of gender and culture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Kirk, C.P. Entrepreneurial passion as mediator of the self-efficacy to persistence relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.; Shamsudin, F.M.; Ismail, H.C. Exploring potential women entrepreneurs among international women students: The effects of the theory of planned behavior on their intention. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 17, 651–657. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, S.; Indarti, N. Entrepreneurial Intention Among Indonesian and Norwegian Students. J. Enterprising Cult. 2004, 12, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Entrepreneurship, adaptation and legitimation: A macro-behavioral perspective. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1987, 8, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighetti, A.; Caricati, L.; Landini, F.; Monacelli, N. Entrepreneurial intention in the time of crisis: A field study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 835–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L.; Isaksen, E. New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 866–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, A.; Kolvereid, L. Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1999, 11, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, R.S. Entrepreneurship, Library of Economics and Liberty. 2008. Available online: www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Entrepreneurship.html (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Baumgartner, J.; Yi, Y. An investigation into the role of intentions as mediators of the attitude-behavior relationship. J. Econ. Psychol. 1989, 10, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The Social Dimension of Entrepreneurship; Pretince-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero, A. The displaced, uncomfortable entrepreneur. Psychol. Today 1975, 9, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero, A. Some social dimensions of entrepreneurship; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. Learned Optimism; AA Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 28, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, L.M.; Hang, P.T.T.; Hoang, N.; Trang, T.K.; Anh, D.V.P.; Nga, M.D.T. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Vietnam Report 2017/2018. Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry–VCCI; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association-GERA: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IMF-International Monetary Fund. Fiscal Policies for Innovation and Growth. 2016. Available online: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/imported-flagship issues/external/pubs/ft/fm/2016/01/pdf/_fmc2pdf.ashx (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Qureshi, M.S.; Mian, S.A. Global entrepreneurship monitor Pakistan report 2012. In Global report, GEM 2012; Institute of Business Administration: Karachi, Pakistan, 2012; Available online: https://gemconsortium.org/economy-profiles/pakistan (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Liberman, N.; Sagristano, M.D.; Trope, Y. The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J.O. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WESO-World Employment and Social Outlook; Trends; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Mueller, S.L. Gender gaps in potential for entrepreneurship across countries and cultures. J. Dev. Entrep. 2004, 9, 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P. The quest for invisibility: Female entrepreneurs and the masculine norm of entrepreneurship. Gend. Work Organ. 2006, 13, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Farooq, O.; Sultana, N.; Farooq, M. Determinants of individuals’ entrepreneurial intentions: A gender-comparative study. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keele, L.; Tingley, D.; Yamamoto, T. Identifying mechanisms behind policy interventions via causal mediation analysis. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2015, 34, 937–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heuer, A.; Liñán, F. Testing alternative measures of subjective norms in entrepreneurial intention models. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2013, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarstedt, M.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M. Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. Adv. Int. Mark. 2011, 22, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Advances in International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Lukas, B. Marketing Research, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: North Ryde, NSW, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise education: Influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda, G.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L. Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Guidelines and empirical examples. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Latan, H., Noonan, R., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valliere, D. Multidimensional entrepreneurial intent: An internationally validated measurement approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pakistan (n = 243) | Vietnam (n = 204) | Total Sample (n = 447) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 111 (45.7%) | 61 (29.9%) | 172 (38.5%) |

| Female | 132 (54.3%) | 143 (70.1%) | 275 (61.5%) |

| Entrepreneurial Network | |||

| Yes | 158 (65.0%) | 111 (54.4%) | 269 (60.2%) |

| No | 85 (35.0%) | 93 (45.6%) | 178 (39.8%) |

| Studying Business | |||

| Yes | 162 (66.7%) | 125 (61.3%) | 287 (64.2%) |

| No | 81 (33.3%) | 79 (38.7%) | 160 (35.8%) |

| Studied Entrepreneurship | |||

| Yes | 107 (44.0%) | 167 (81.9%) | 274 (61.3%) |

| No | 136 (56.0%) | 37 (18.1%) | 173 (38.7%) |

| Parents Doing Business | |||

| Yes | 134 (55.1%) | 98 (48.0%) | 232 (51.9%) |

| No | 109 (44.9%) | 106 (52.0%) | 215 (48.1%) |

| Working somewhere | |||

| Yes | 53 (21.8%) | 134 (65.7%) | 187 (41.8%) |

| No | 190 (78.2%) | 70 (34.3%) | 260 (58.2%) |

| Short-Term Entrepreneurial Intention | Long-Term Entrepreneurial Intention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | Vietnam | Pakistan | Vietnam | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 5.96 | 1.35 | 4.07 | 1.66 | 5.99 | 1.31 | 4.58 | 1.77 |

| Female | 4.57 | 1.79 | 3.61 | 1.51 | 4.60 | 1.81 | 3.97 | 1.64 |

| Entrepreneurial Network | ||||||||

| Yes | 5.30 | 1.76 | 3.92 | 1.57 | 5.35 | 1.74 | 4.37 | 1.68 |

| No | 5.03 | 1.71 | 3.54 | 1.56 | 5.02 | 1.73 | 3.89 | 1.70 |

| Studying Business | ||||||||

| Yes | 5.31 | 1.71 | 4.10 | 1.55 | 5.31 | 1.73 | 4.56 | 1.70 |

| No | 5.01 | 1.81 | 3.19 | 1.45 | 5.09 | 1.77 | 3.49 | 1.49 |

| Studied Entrepreneurship | ||||||||

| Yes | 5.08 | 1.79 | 3.87 | 1.55 | 4.99 | 1.81 | 4.23 | 1.69 |

| No | 5.30 | 1.71 | 3.19 | 1.54 | 5.43 | 1.66 | 3.78 | 1.73 |

| Parents Doing Business | ||||||||

| Yes | 4.98 | 1.86 | 3.97 | 1.65 | 5.04 | 1.83 | 4.39 | 1.74 |

| No | 5.49 | 1.56 | 3.54 | 1.47 | 5.48 | 1.59 | 3.93 | 1.65 |

| Working somewhere | ||||||||

| Yes | 5.29 | 1.66 | 3.60 | 1.56 | 5.27 | 1.61 | 4.10 | 1.68 |

| No | 5.18 | 1.77 | 4.03 | 1.55 | 5.22 | 1.78 | 4.25 | 1.75 |

| Full Sample | Pakistan | Vietnam | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Loadings | α | CR | AVE | α | CR | AVE | α | CR | AVE |

| Attitude (ATT) | 0.856 | 0.896 | 0.634 | 0.837 | 0.884 | 0.605 | 0.864 | 0.903 | 0.652 | |

| “ATT1. A career as an entrepreneur is attractive to me” | 0.773 | |||||||||

| “ATT2. If I had the opportunity and resources, I would like to start a company” | 0.783 | |||||||||

| “ATT3. Being an entrepreneur would entail great satisfaction for me” | 0.840 | |||||||||

| “ATT4. Among various options, I would rather be an entrepreneur” | 0.832 | |||||||||

| “ATT5. I believe that if I will start my business, I will certainly succeed” | 0.752 | |||||||||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | 0.836 | 0.901 | 0.753 | 0.779 | 0.870 | 0.691 | 0.858 | 0.913 | 0.778 | |

| “SN1. I believe that people think I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur” | 0.866 | |||||||||

| “SN2. My friends see entrepreneurship as a logical choice for me” | 0.893 | |||||||||

| “SN3. My parents are positively oriented toward a career as an entrepreneur” | 0.844 | |||||||||

| Perceived Behavior Control (PBC) | 0.916 | 0.935 | 0.704 | 0.881 | 0.909 | 0.626 | 0.918 | 0.936 | 0.709 | |

| “PBC1. To start a company and keep it working would be easy for me” | 0.807 | |||||||||

| “PBC2. I am prepared to start a viable company” | 0.841 | |||||||||

| “PBC3. I can control the creation process of a new company” | 0.856 | |||||||||

| “PBC4. I know the necessary practical details to start a company” | 0.823 | |||||||||

| “PBC5. I know how to develop an entrepreneurial project” | 0.861 | |||||||||

| “PBC6. If I tried to start a company, I would have a high probability of succeeding” | 0.847 | |||||||||

| Short-Term Entrepreneurial Intention (STEI) | 0.824 | 0.919 | 0.850 | 0.815 | 0.915 | 0.844 | 0.785 | 0.902 | 0.822 | |

| “STEI1. I am determined to create a company in the future” | 0.925 | |||||||||

| “STEI2. After my graduation, I intend to create my own company or business” | 0.919 | |||||||||

| Long-Term Entrepreneurial Intention (LTEI) | 0.851 | 0.931 | 0.870 | 0.822 | 0.918 | 0.849 | 0.863 | 0.936 | 0.879 | |

| “LTEI1. I have a very serious thought about starting my own company” | 0.939 | |||||||||

| “LTEI2. I intend someday to start my own company or business” | 0.927 | |||||||||

| ATT | Gender | LTEI | PBC | SN | STEI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.797 | |||||

| Gender | −0.231 | 1.000 | ||||

| LTEI | 0.668 | −0.328 | 0.933 | |||

| PBC | 0.526 | −0.207 | 0.538 | 0.839 | ||

| SN | 0.679 | −0.271 | 0.609 | 0.649 | 0.868 | |

| STEI | 0.740 | −0.326 | 0.822 | 0.590 | 0.687 | 0.922 |

| Country | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Full Sample | Pakistan | Vietnam | Hypotheses |

| Gender → STEI | −0.121 *** | −0.156 *** | −0.067 | Control variable |

| Gender → LTEI | −0.067 * | −0.081 * | −0.064 | Control variable |

| Entrepreneurial Temporal Intention | ||||

| STEI → LTEI | 0.671 *** | 0.672 *** | 0.61 *** | H1 |

| Short-Term Entrepreneurial Intention | ||||

| ATT → STEI | 0.469 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.51 *** | H2 |

| SN → STEI | 0.222 *** | 0.255 ** | 0.094 | H3 |

| PBC → STEI | 0.174 ** | 0.067 | 0.262 *** | H4 |

| Long-Term Entrepreneurial Intention | ||||

| ATT → LTEI | 0.117 | 0.113 | 0.112 | H5 |

| SN → LTEI | 0.012 | 0.04 | −0.029 | H6 |

| PBC → LTEI | 0.059 | 0.007 | 0.177 ** | H7 |

| Subjective Norms | ||||

| SN → ATT | 0.679 *** | 0.674 *** | 0.637 *** | H8 |

| SN → PBC | 0.542 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.561 *** | H9 |

| Attitude | ||||

| ATT → PBC | 0.158 ** | 0.176 * | 0.16 * | H10 |

| Pakistan Sample | Original Sample (O) | p-Values | Lower Threshold | Upper Threshold | Hypothesis | Mediation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN → ATT → STEI | 0.324 | 0.000 | 0.221 | 0.44 | H11 | Complementary (partial mediation) |

| SN → ATT → LTEI | 0.076 | 0.266 | −0.053 | 0.213 | H12 | No effect (no mediation) |

| SN → ATT → STEI → LTEI | 0.218 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.336 | H13 | Full mediation |

| SN → ATT → PBC | 0.119 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.228 | H14 | Complementary (partial mediation) |

| SN → ATT → PBC → STEI | 0.008 | 0.426 | −0.006 | 0.037 | H15 | Partial mediation |

| SN → ATT → PBC → LTEI | 0.001 | 0.911 | −0.015 | 0.017 | H16 | Partial mediation |

| SN → ATT → PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.005 | 0.429 | −0.004 | 0.024 | H17 | Full mediation |

| SN → PBC → STEI | 0.027 | 0.366 | −0.025 | 0.092 | H18 | Direct-only (no mediation) |

| SN → PBC → LTEI | 0.003 | 0.903 | −0.047 | 0.051 | H19 | No effect (no mediation) |

| SN → PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.018 | 0.357 | −0.018 | 0.06 | H20 | Full mediation |

| ATT → PBC → STEI | 0.012 | 0.418 | −0.008 | 0.053 | H21 | Direct-only (no mediation) |

| ATT → PBC → LTEI | 0.001 | 0.910 | −0.022 | 0.025 | H22 | No effect (no mediation) |

| ATT → PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.008 | 0.421 | −0.005 | 0.036 | H23 | Partial mediation |

| ATT → STEI → LTEI | 0.323 | 0.000 | 0.191 | 0.486 | H24 | Indirect-only (full mediation) |

| SN → STEI → LTEI | 0.171 | 0.009 | 0.053 | 0.311 | H25 | Indirect-only (full mediation) |

| PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.045 | 0.339 | −0.047 | 0.136 | H26 | No effect (no mediation) |

| Vietnam Sample | Original Sample (O) | p-Values | Lower Threshold | Upper Threshold | Hypothesis | Mediation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN → ATT → STEI | 0.325 | 0.000 | 0.236 | 0.425 | H11 | Indirect-only (full mediation) |

| SN → ATT → LTEI | 0.072 | 0.122 | −0.014 | 0.167 | H12 | No effect (no mediation) |

| SN → ATT → STEI → LTEI | 0.198 | 0.000 | 0.134 | 0.279 | H13 | Full mediation |

| SN → ATT → PBC | 0.102 | 0.051 | −0.003 | 0.203 | H14 | Complementary (partial mediation) |

| SN → ATT → PBC → STEI | 0.027 | 0.099 | 0.001 | 0.066 | H15 | Full mediation |

| SN → ATT → PBC → LTEI | 0.018 | 0.117 | 0.001 | 0.048 | H16 | Full mediation |

| SN → ATT → PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.016 | 0.098 | 0.001 | 0.041 | H17 | Full mediation |

| SN → PBC → STEI | 0.147 | 0.001 | 0.072 | 0.242 | H18 | Indirect-only (full mediation) |

| SN → PBC → LTEI | 0.099 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.198 | H19 | Indirect-only (full mediation) |

| SN → PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.09 | 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.156 | H20 | Full mediation |

| ATT → PBC → STEI | 0.028 | 0.112 | 0.002 | 0.073 | H21 | Complementary (partial mediation) |

| ATT → PBC → LTEI | 0.042 | 0.098 | 0.002 | 0.103 | H22 | Indirect-only (full mediation) |

| ATT → PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.026 | 0.099 | 0.002 | 0.065 | H23 | Partial mediation |

| ATT → STEI → LTEI | 0.311 | 0.000 | 0.216 | 0.417 | H24 | Indirect-only (full mediation) |

| SN → STEI → LTEI | 0.057 | 0.247 | −0.028 | 0.168 | H25 | No effect (no mediation) |

| PBC → STEI → LTEI | 0.16 | 0.000 | 0.082 | 0.257 | H26 | Complementary (partial mediation) |

| Full Sample | Pakistan | Vietnam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (β) | p-Values | Coefficient (β) | p-Values | Coefficient (β) | p-Values | |

| ATT → STEI | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.012 | 0.418 | 0.042 | 0.098 |

| ATT → LTEI | 0.343 | 0.000 | 0.332 | 0.000 | 0.365 | 0.000 |

| SN → STEI | 0.432 | 0.000 | 0.359 | 0.000 | 0.499 | 0.000 |

| SN → LTEI | 0.557 | 0.000 | 0.492 | 0.000 | 0.550 | 0.000 |

| SN → PBC | 0.107 | 0.002 | 0.119 | 0.023 | 0.102 | 0.051 |

| PBC → LTEI | 0.117 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 0.339 | 0.160 | 0.000 |

| Pakistan vs. Vietnam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Configurational Invariance | c | 5% Quantile of cu | Partial Measurement Invariance |

| LTEI | Yes | 1.000 | 1.000 | Yes |

| STEI | Yes | 0.999 | 1.000 | No |

| ATT | Yes | 1.000 | 0.999 | Yes |

| PBC | Yes | 0.999 | 0.999 | Yes |

| SN | Yes | 0.998 | 0.999 | No |

| Gender | Yes | 1.000 | 1.000 | Yes |

| Path Coefficients diff. (|Vietnam−Pakistan|) | p-Value (Vietnam vs. Pakistan) | |

|---|---|---|

| ATT → STEI | 0.030 | 0.380 |

| ATT → LTEI | 0.000 | 0.498 |

| ATT → PBC | 0.016 | 0.555 |

| SN → STEI | 0.161 | 0.918 |

| SN → LTEI | 0.070 | 0.744 |

| SN → ATT | 0.037 | 0.728 |

| SN → PBC | 0.157 | 0.077 |

| PBC → STEI | 0.196 | 0.023 |

| PBC → LTEI | 0.169 | 0.025 |

| STEI → LTEI | 0.063 | 0.690 |

| Gender → STEI | 0.089 | 0.072 |

| Gender → LTEI | 0.017 | 0.382 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Full Sample | Pakistan Sample | Vietnam Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | STEI → LTEI | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| H2 | ATT → STEI | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| H3 | SN → STEI | Supported | Supported | Not Supported |

| H4 | PBC → STEI | Supported | Not Supported | Supported |

| H5 | ATT → LTEI | Not Supported | Not Supported | Not Supported |

| H6 | SN → LTEI | Not Supported | Not Supported | Not Supported |

| H7 | PBC → LTEI | Not Supported | Not Supported | Supported |

| H8 | SN → ATT | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| H9 | SN → PBC | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| H10 | ATT → PBC | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| H11 | SN → ATT → STEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H12 | SN → ATT → LTEI | No Mediation | No mediation | |

| H13 | SN → ATT → STEI → LTEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H14 | SN → ATT → PBC | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H15 | SN → ATT → PBC → STEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H16 | SN → ATT → PBC → LTEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H17 | SN → ATT → PBC → STEI → LTEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H18 | SN → PBC → STEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H19 | SN → PBC → LTEI | No Mediation | Mediation | |

| H20 | SN → PBC → STEI → LTEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H21 | ATT → PBC → STEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H22 | ATT → PBC → LTEI | No Mediation | Mediation | |

| H23 | ATT → PBC → STEI → LTEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H24 | ATT → STEI → LTEI | Mediation | Mediation | |

| H25 | SN → STEI → LTEI | Mediation | No mediation | |

| H26 | PBC → STEI → LTEI | No Mediation | Mediation | |

| H27 | Difference: Pakistan vs. Vietnam | Partially supported | Partially supported | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nasar, A.; Kamarudin, S.; Rizal, A.M.; Ngoc, V.T.B.; Shoaib, S.M. Short-Term and Long-Term Entrepreneurial Intention Comparison between Pakistan and Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236529

Nasar A, Kamarudin S, Rizal AM, Ngoc VTB, Shoaib SM. Short-Term and Long-Term Entrepreneurial Intention Comparison between Pakistan and Vietnam. Sustainability. 2019; 11(23):6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236529

Chicago/Turabian StyleNasar, Asim, Suzilawati Kamarudin, Adriana Mohd Rizal, Vu Thi Bich Ngoc, and Samar Mohammad Shoaib. 2019. "Short-Term and Long-Term Entrepreneurial Intention Comparison between Pakistan and Vietnam" Sustainability 11, no. 23: 6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236529