1. Introduction

Corporate marketing programs primarily focus on attaining consumer loyalty. Such loyalty is often reflected through favorable attitudes toward the company in the consumer-brand relationship and in product evaluations. The main purpose is to enhance competitive advantages in the marketplace. In today’s rapidly changing marketing environment, building strong relationships and brand loyalty with the consumer is becoming increasingly important for companies. Some studies have argued that corporations should deliver their brand message and sell their products to consumers while considering social and environmental issues. Strategies that focus on shared issues increase consumers’ interest in purchasing products or services from such companies [

1].

Maintaining a relationship with the consumer and building brand loyalty are major challenges in the current marketing environment [

2]. Today’s highly competitive marketplace makes these challenges even more daunting. For instance, modern society demands companies to behave responsibly and ethically toward their stakeholders [

3,

4].

Research on ethical marketing strategies, which are formulated to gain competitive advantage, has been conducted for almost all business areas [

5,

6]. Ethical marketing practices by a company affect the daily routine of consumer consumption activity [

7]. All ethical marketing practices by a company are closely related to purchasing products or services, regardless of whether the company is aware of the strengths and weaknesses of the consumer purchasing power [

8]. Corporate managers and marketers have realized the importance of ethical practice in the advancement of business sustainability [

7,

9,

10], promotion of ethical management [

6], and general marketing issues (e.g., product safety, pricing, and advertising) [

11]. An ethical, or unethical, corporation’s business conduct is inherently likened to its overall reputation and evaluation; it also emphasizes the corporation’s essential factors to remain competitive in the marketplace [

7,

9,

10,

12].

Despite the apparent importance of ethical marketing practice with respect to relationship building, product evaluation, and strong brand loyalty, only a few studies have examined the marketing mix strategy—such as, product, price, place, and promotion—from an ethical issues standpoint as having a critical influence on consumer attitude formation (e.g., product evaluation and brand loyalty). That is, how the “marketing mix strategy from ethical issues” functions reflects the consumer product evaluation, brand perception, and brand loyalty.

The hypothesis, or scope, of this article is to examine the components of the marketing mix from an ethical perspective and their effect on the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality in B2C transactions. We also examine whether the consumer-brand relationship quality and consumer-perceived product quality affect corporate brand loyalty. The theoretical and practical implications of the findings and the study’s limitations and directions for future research are discussed toward the end of the paper.

3. Hypotheses and Theoretical Model

The marketing mix strategy with ethical views pertain to moral beliefs and behavior that inform corporate activity, in which ethical consideration is applied to marketing decisions [

64]. The ethical marketing practice problems occur more frequently in gray areas (e.g., underground economy) in which legal acts can occasionally be unethical or in which the legitimacy or ethicality of behavior is uncertain. In such situations, the role of marketing ethics has become increasingly important. Forming relationships between brands and consumers affects dynamic interaction between consumers and products, creating a positive effect on the brand experience [

65]. A higher level of ethical responsibility leads to an increase in trust between the company and stakeholders [

66].

Brands and consumers mutually affect each other by their interaction. The relationship between a consumer and brand reflects the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes that inform a relationship between two people [

67]. Here, we find a contact point between the ethical marketing practice and consumer-brand relationship quality because consumers evaluate a brand and build a relationship quality through a series of processes, which include perception of and experience with a brand and interaction with the brand. Ethical marketing practice is one of the most visible fields in a company’s diverse activities that is observable by consumers. Additionally, ethical marketing practice is an important factor that influences consumer perceptions and evaluation of a brand.

As noted above, in the past, moral problems in marketing have largely involved product safety, price fixing, bribery, deceptive advertising, and anti-social or unethical information collection. Lately, such moral problems have arisen in new aspects as companies adjust to environmental change [

7,

9,

10,

12,

68]. Ethical problems involving fairness, probity, and product, and human resource management are affecting subjective evaluations of product quality more now than in the past.

Deceptive prices mislead the consumer from the basic feature of purchase. Setting the right price in the marketplace is one of the best means to improve the relationship between a company and consumer [

1,

31]. Truthful information about the product is needed to protect the consumer, and the negative effect of advertisements causes consumers to reach irrational decisions [

29,

30,

69]. Product advertising should be easily understandable to common consumers. This point is in the code of ethics for better business bureau organizations [

37,

40,

41,

70]. The above discussion implies that ethical marketing practice in the firm’s marketing mix can cause consumers to make irrational decisions, which might ultimately generate harmful consequences for the company. Assuming there is a direct relationship between a corporation’s ethical marketing practice and its consumer-brand relationship quality, we propose the following hypotheses:

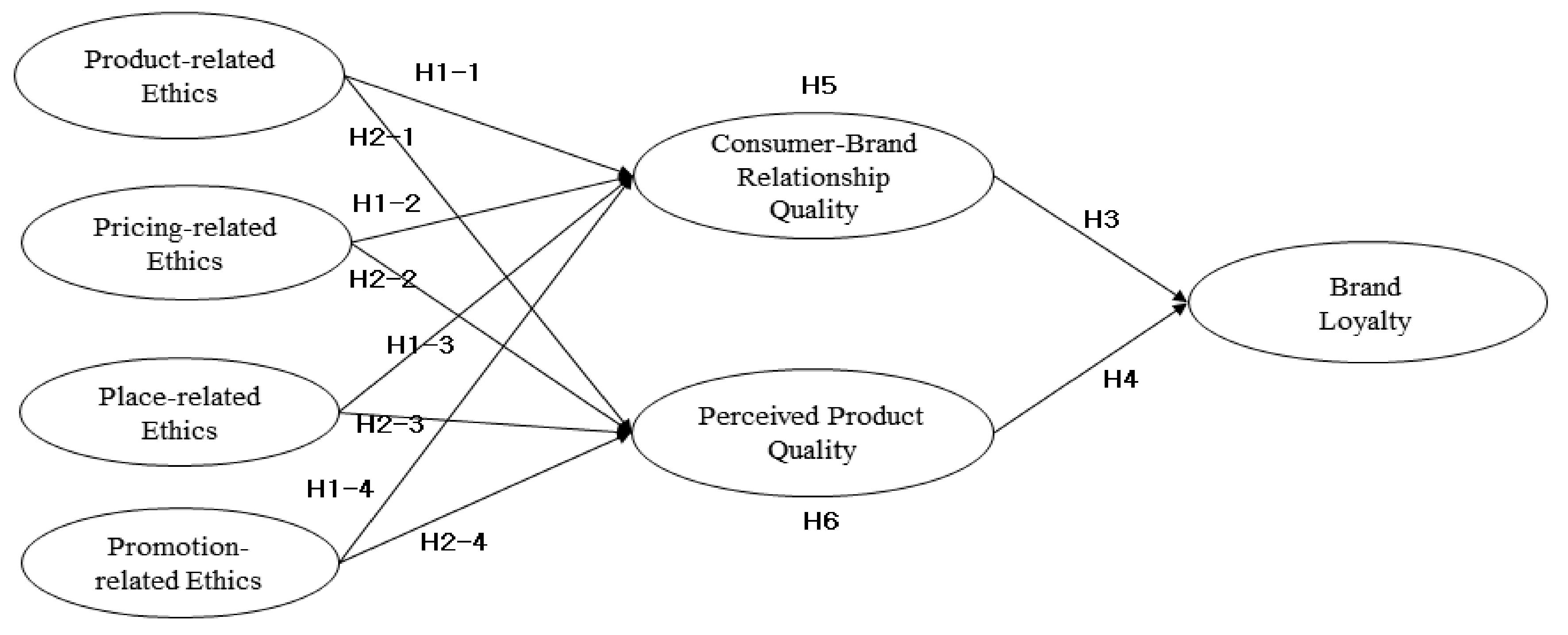

Hypothesis 1-1 (H1-1). The product-related ethics will have a positive effect on consumer-brand relationship quality.

Hypothesis 1-2 (H1-2). The price-related ethics will have a positive effect on consumer-brand relationship quality.

Hypothesis 1-3 (H1-3). The place-related ethics will have a positive effect on consumer-brand relationship quality.

Hypothesis 1-4 (H1-4). The promotion-related ethics will have a positive effect on consumer-brand relationship quality.

Perceived product quality must satisfy consumer needs and wants, such as product safety and health standards [

71] and the environment [

72]. Within high-quality products, consumers can select a brand that is deemed to deliver ethical values and behave responsibly [

73]. Based on these studies of the concept of product quality, we define product quality as the subjective quality that a consumer perceives in a product. A firm that establishes a reputation for marketing its products or services in a morally responsible manner receives respect and trust from customers, suppliers, employees, and stakeholders because the company strikes the right balance between the rights of interested parties and its own interests when making decisions or implementing plans [

74]. Companies can achieve continuous benefit only when their transactions are based on reciprocal relationships between the interested parties. Assuming there is a direct relationship between a corporation’s ethical marketing practice such as marketing mix strategy and its perceived-product quality, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2-1 (H2-1). The product-related ethics will have an influence on perceived product quality.

Hypothesis 2-2 (H2-2). The price-related ethics will have an influence on perceived product quality.

Hypothesis 2-3 (H2-3). The place-related ethics will have an influence on perceived product quality.

Hypothesis 2-4 (H2-4). The promotion-related ethics will have an influence on perceived product quality.

Marketing is one of the most visible fields of a company’s diverse activities that is observable by consumers. Therefore, the ethical propriety of a firm’s marketing practices is an important factor that affects the perception and evaluation of a brand [

67]. Blackstone argues that consumer-brand relationship quality is a critical element in enabling consumers to trust a company and find its products satisfactory. Consumers evaluate a brand by applying emotional and relational criteria to activities, community, expectations, and stories when they choose a brand, and a consumer-brand relationship is built during this process. Consumers assess the value of a brand by reference to their own experience rather than focusing on the intrinsic attributes of a product [

75].

According to Keller, “consumer-brand resonance is the final stage in the establishment of a brand asset, a phenomenon related to the brand-consumer relationship” [

76]. Moreover, “consumers engage in brand loyalty behavior, active participation, brand immersion, and community spirit at this stage of the branding process” [

55,

56,

77,

78,

79]. Previous work verifies that the consumer-brand relationship improves brand loyalty [

55,

56,

80]. Aggarwal argues that the consumer-brand relationship necessarily accompanies financial exchange, which differentiates it from interpersonal relationships, finding that consumers tend to form unilateral affective relationships with a brand [

51]. Establishing a strong consumer-brand relationship is the ultimate goal of branding because a consumer-brand relationship can also promote consumer loyalty to a brand [

77,

78,

80].

Previous studies have found that perceived product quality has a positive effect on customer satisfaction, commitment, and brand loyalty [

81,

82,

83]. Perceived quality should lead consumers to trust and identify with a brand. Moreover, perceived quality is closely related to customer satisfaction because people with higher quality perceptions of a brand also exhibit higher customer satisfaction [

84,

85]. Perceived quality is attributed to such a company through beliefs [

86]. Pyun et al. found that people who exhibit or report high perceived brand quality are more likely to recognize a perceived brand [

87].

Perceived quality can be viewed as the difference between overall quality and undetected quality. Furthermore, perceived quality can lead to consumer satisfaction, which is determined by perceived performance and expectation [

88]. The quality of a product includes its capability to perform to the customers’ needs and expectations [

89]. Brand loyalty is expected to result from consumers’ overall disposition toward the brand, and brand loyalty is treated as the final outcome of a consumer’s brand evaluation [

90]. Brand loyalty is viewed in terms of behavior and attitude in the marketing literature. For this reason, the consumer-brand relationship and product quality might be expected to play an important, influential role and affect brand loyalty.

Hence, this study proposes the following hypothesis based on the concept that the level of the consumer-brand relationship and product quality will have a significant effect on the formation of brand loyalty. We assume that a company’s marketing ethics are related to the consumer-brand relationship and that the consumer-brand relationship, in turn, affects brand loyalty. These observations lead to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Consumer-brand relationship quality will have a positive effect on brand loyalty.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Perceived product quality will have a positive effect on brand loyalty.

How consumers perceive a company is becoming increasingly diversified. Some scholar mentioned that

“companies are pursuing sustainable corporate growth to improve relationships with consumers or to maintain amicable relationships with them” [

55]. As companies continue to develop ethical marketing practices such as a marketing mix, it will be very meaningful to study consumer perceptions of the activities, consumer-brand relationship, perceived product quality, and brand loyalty. In this study, we chose the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality as mediating variables. We examined the mediating effects of these two variables and assumed that a company’s ethical marketing practice are related to the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality and that the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality affect brand loyalty. Based on the literature review and previous discussion, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). The ethical marketing practices (product-related ethics: H5-1; pricing-related ethics: H5-2; place-related ethics: H5-3; and promotion-related ethics: H5-4) will affect brand loyalty through the mediating effects of consumer-brand relationship quality.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). The ethical marketing practices (product-related ethics: H6-1; pricing-related ethics: H6-2; place-related ethics: H6-3; and promotion-related ethics: H6-4) will affect brand loyalty through the mediating effects of perceived product quality.

We propose the above research hypotheses to inform our investigation of the role of ethical marketing practices on the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality in B2C transactions. Based on the research hypotheses and theoretical considerations, we developed our research model (see

Figure 1).

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Questionnaire Development and Data Collection

Before distributing the survey questionnaire, we checked whether there were any conceptual errors in the survey questions by consulting researchers and professors in business administration. After the pretest, the questionnaire form was developed. The questionnaire used in this study and based on the literature review are related to independent and dependent variables.

Participants (1200 consumer panel members who registered with a research company) were then contacted by phone and were asked to participate in this study. Investigator asked participants to visit to the online survey website. The survey method suggested by previous study was applied to this study [

55,

56]. Investigator gave them

$5.00 gift cards to increase the response rate. This study conducted a survey of a panel of the company’s consumers who had knowledge of the company’s ethical marketing issues and had experience with the company, products, and brand (e.g., Hanwha group is a lager corporation in Korea) more than once. This survey was reasonable for participants because this company and product are familiar to them and it was not difficult to evaluate the company, product, and brand when they answered the questions.

The instruments consisted of two parts, with demographic questions placed at the beginning. The second part of the survey included questions on ethical marketing practices (e.g., product-, pricing-, place-, and promotion-related ethics), the consumer-brand relationship, and perceived product quality and brand loyalty.

Table 1 provides the demographic characteristics of the sample participants.

4.2. Instrument Construction

The operational definition of ethical marketing practices used in this study is based on the literature on ethical marketing and business. Ethical marketing practices refer to

“moral judgment and behavior standards in marketing practice in a marketing area” [

1,

9,

91]. We categorize the marketing mix strategy from ethical issues as product-related, price-related, place-related, and promotion-related ethics [

1,

31,

33,

64,

69,

72].

Product-related ethical issues constitute the level of product safety, quality, eco-friendliness, packaging and branding, and warranty (e.g., Is the product safety information clearly indicated on the packaging?).

Price-related ethical issues constitute using predatory pricing strategies, illegal pricing, and fraudulent or false pricing (e.g., Does the manufacturer refrain from using a predatory pricing strategy of intentionally lowering prices to eradicate competitors?).

Place-related ethical issues constitute the degree of the sales policy, level of partnership, and degree of transparent transaction (e.g., Does the manufacturer refrain from controlling transactions by abusing its status?).

Promotion-related ethical issues constitute advertising under legal legislation and degree of misleading or deceptive aspects (e.g., Does the manufacturer refrain from providing fraudulent, false, and exaggerated advertisements to consumers).

The study survey is based on the above definitions, with questionnaire items drawn from extant studies on ethical marketing practices. Twenty-eight items measure the marketing mix strategy from ethical issue, namely, seven sub-questions for product-related ethics, seven sub-questions for pricing-related ethics, eight sub-questions for place-related ethics, and six sub-questions for promotion-related ethics.

The operational definition of the consumer-brand relationship quality is based on the general definition of a brand. A brand, which is often visible as a mark of possession on a product, represents the differentiation in value of a product relative to a competitor’s products and connects companies to consumers. In this respect, a consumer-brand relationship quality refers to

“the belief that using a certain brand provides value and benefit” [

43,

46,

78,

88]. We revise and complement the scale for the consumer-brand relationship used in extant studies to fit the current study and, thus, measure the consumer-brand relationship using 15 questions (e.g., I really like to talk about the company’s brand that I like with others).

Perceived product quality is defined as follows: “An overall product evaluation was based on consumer perceptions of the product’s quality and of its overall excellence or superiority such as being of high quality, being a dedicated design product, and having fine workmanship” [

52,

71]. For example, “This company’s product has a dedicated design.” After recomposing the questions used in extant studies, we measure perceived product quality using three questionnaire items [

52].

Brand loyalty is defined as “consumers’ attachment to, trust in, and feeling toward a certain brand [

88] and the frequency of preference for a certain brand leading to repeated purchases” [

56]. It is measured by four items after correcting and modifying the questionnaire items from extant studies to fit the current study [

56,

88,

90]: For example, “I am willing to repurchase this company’s product in the near future.” Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement on the structured questions on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). All questionnaire items are measured using a five-point Likert scale (see

Appendix A).

6. Conclusions and Discussion

We attempted to investigate the components of marketing mix from the standpoint of ethical views and their effect on the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. We also examined whether the consumer-brand relationship quality and consumer-perceived product quality affect corporate brand loyalty.

The results indicate that except price-related ethics, the remaining three marketing mix strategies based on ethical issues are closely related to the consumer-brand relationship. Product-related ethical issues have a positive effect on the consumer-brand relationship quality as well as perceived product quality. Thus, consumers are willing to purchase a product characterized by high level of product safety and quality, well-designed packaging and brand, and eco-friendliness. During product evaluation, consumers’ attitudes toward a company are formed in consideration of ethical issues. Product-related ethical issues are crucial when consumers evaluate perceived product quality. The results support the proposed research model statistically and significantly. That is, the corporate marketing mix strategy from ethical issues had an important function in generating a consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. The path outcome for product-related ethics and the consumer-brand relationship quality accurately reflects the results found in the extant literature [

102,

103].

Price-related ethical issues are critical when a consumer is focused on building a strong relationship with a corporation and its brand. This evaluation is often based on whether the company is using predatory pricing strategy, illegal pricing, and fraudulent pricing. An unethical pricing strategy has a negative effect on consumer attitude formation, which includes relationship building with a brand. However, we did not find a correlation between pricing and perceived product quality. Seemingly, consumers are fine with having different perceptions of pricing and product quality. Unethical pricing also does not influence perceived product quality. Pricing-related ethical issues form a set of vital factors that consumers consider when they seek to build a strong relationship with a corporation and its brand by evaluating perceived product quality.

Moreover, place-related ethical issues have a positive effect on the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. Hence, there is a need to improve the relationship with consumers through better place-related ethical issues. One strategy is to strengthen certain areas of ethical marketing practices. For example, in marketing, the role of salespersons is crucial—fostering interpersonal relationships is key. When consumers are provided with products they want, they not only prefer ethical acts through honest distribution channels but also wish to receive products that are customized for their own companies. These desires imply the importance of establishing a sound ethical approach to achieving proper and customized distribution. Some factors such as the degree of sales policy, level of partnership, and degree of transparent transaction in place-related ethical issues also considerably influence relationship-building with consumers and product quality evaluation.

Promotion-related ethical issues have a positive effect on the consumer-brand relationship quality and perceived product quality, where the latter two can be reinforced directly only when a company’s promotion-related ethics are high. To build a relationship with the consumer, the company should hone authentic communication. When truthful and accurate information about a product, such as its price through advertising, is communicated, the consumer is likely to exhibit high trustworthiness in the corporation and its brand. Factors such as advertising under legal legislation and degree of misleading or deceptive aspects are thus critical when building a strong relationship with the brand; they also improve product quality. Our findings identify factors that should be considered when building a relationship that involves ethical marketing practices, relationship quality, and brand loyalty. The factors of product-, pricing-, and promotion-related ethics—areas of ethical marketing practices—can be used to evaluate the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. If a company improves its relationship quality through improved product-related ethics, we expect a corresponding effect on brand loyalty through brand and emotional relationships with consumers than a direct effect on brand loyalty.

Management- and marketing-related ethics typically involve resolving problems that individuals experience in social life; these problems relate to specific circumstances within corporate management. Within the sphere of corporate ethics, ethical marketing practices involve the relationship between moral beliefs and behavior and corporate marketing practices.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The effects of ethical marketing practices on brand loyalty in B2C transactions and the involvement of the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality have important implications. Through our study, we make the following contributions to the extant literature as well as present some practical implications. Our study is different from extant studies on the relationship between ethical marketing practices and brand loyalty because the latter have focused primarily on B2C transactions. Most studies on B2C transactions find that product-, pricing-, place-, and promotion-related ethics have positive effects on brand loyalty or quality. However, it is necessary to induce brand loyalty primarily through improving and reinforcing pricing- or place-related ethics in B2C transactions. However, our contribution is novel because we use an improved research model to analyze the relationship between ethical marketing practices and the consumer-brand relationship, product quality, and brand loyalty, which is common in B2C transactions. The relationships that form between brands and consumers affect the dynamic interactions between consumers and products, which positively affects the brand experience. We thus assert that consumer experiences could be enriched further when the interaction between a consumer and a product includes increased physical contact time.

6.2. Managerial Implications

This study systematically analyzes the mediating effects of the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality when investigating factors that affect mutual transactional relationships in B2C transactions. These factors affect brand loyalty significantly. We confirmed a significant correlation between ethical marketing practices, which form the basis of transactions and relationship quality.

The findings confirmed that product ethics affect brand loyalty through the mediating effects of the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. That is, companies should develop an emotional approach to reaching consumers when preparing for the upcoming fourth industrial revolution. Companies that anticipate this new era must improve their product offerings not only through safety improvements, better warranties, and eco-friendliness, but also by reconfiguring the role of salespeople to ensure their success.

Pricing-related ethics should also be approached from a new perspective. When a company provides fair prices, it earns the trust of customers and thus strengthens its relationships. Our results concerning the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality prove this point. Considering the relationship between pricing-related ethics and brand loyalty, consumers of a brand generally want to be provided with a product at more competitive prices than what the consumers of competitors must pay. If a supplier does not provide price elasticity by using fair pricing-related ethics, negative effects can be expected concerning brand loyalty.

No direct effect of pricing-related ethics on brand loyalty was observed, implying that brand loyalty cannot be expected unless pricing-related ethics are reinforced. Moreover, a significantly meaningful relationship between pricing-related ethics and the consumer-brand relationship was observed. In other words, improving pricing-related ethics also improves the consumer-brand relationship quality. However, we found no significant correlation between pricing-related ethics and perceived product quality, implying that reinforcing pricing-related ethics will have very little influence on the perceived product quality.

We also confirmed that a company’s place-related ethics influence brand loyalty through the mediators of the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. However, we found no significant causal relationship between place-related ethics and quality, implying that the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality in a company deteriorate when place-related ethics are strengthened. Like pricing-related ethics, place-related ethics were also found to affect brand loyalty directly. That is, the level of brand loyalty increases when the company’s place-related ethics are high. Place-related ethics were found to have a significant relationship with both the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. A company’s place-related ethics are (in)directly influenced by building brand loyalty through the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. Consumers tend to consider issues such as place-related ethics (e.g., ethical acts through honest distribution channels and customized distribution) when they are evaluating a corporate brand. This finding implies that reinforcing place-related ethics can improve both the consumer-brand relationship and product quality

Promotion-related ethics were found to have a direct influence on brand loyalty. Consumers tend to have positive brand loyalty when promotion-related ethics are strong. Improved promotion-related ethics were found to improve both the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. Promotion-related ethics also affect brand loyalty through the mediating effects of the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality. The common belief that B2C transactions have distinct characteristics was verified in this study. We confirmed that ethical marketing practices (product-, pricing-, place-, and promotion-related ethics) affect brand loyalty through the mediators of the consumer-brand relationship and perceived product quality.

Promotion-related ethics play the most important role in forming strong relationships with consumers in terms of both the consumer-brand relationship and product quality. Questions designed to measure promotion-related ethics are related to trust, such as the company providing false and exaggerated advertisements or false information, trying to facilitate transactions through bribes, and applying oppressive sales pressure. In other words, a relationship with the company can be reinforced in B2C transactions when the company that provides the product is an honest firm that does not abuse its market power. The key takeaway here is that companies can survive in the face of fierce competition only when they establish an ethical culture that prioritizes fair and trust-based transactions aimed at strengthening relationships with companies.

The importance of B2C branding is increasing due to intense competition and the need for differentiation. In light of this, how a buyer perceives a supplier not only affects the supplier’s corporate image, but also determines the quality of the transactional relationship. Moreover, several factors of ethical marketing practices were found to have a significant effect on the evaluation and maintenance of mutual relationships. This study’s results also provide important implications for suppliers’ marketing strategy (e.g., marketing mix strategies). We shed light on how buyers form positive perceptions and images through B2C transactions to create long-term benefits for companies in a corporate environment in which competition is increasingly intense and standardization of technology is difficult to achieve. The findings provide valuable implications to support an effective marketing strategy and ethical marketing practices.

6.3. Limitations and Suggestion for Future Study

Despite its theoretical and practical significance, this study has several limitations. First, the distinct characteristics of B2C transactions were not considered when analyzing the path from marketing ethics to brand loyalty. Additionally, we did not take into account the fact that the outcomes associated with each area of marketing ethics—through the relationship between the mediating variables and dependent variables—vary with business type and other characteristics. Consequently, it is difficult to generalize the results of this study. Future studies should conduct more specific analyses.

Future research should consider the following aspects as well: Ethical marketing practices pertain to both individual factors—such as nations/governments, culture, religion, gender, education, employment, and individuality—and circumstantial factors—such as reference groups, compensation-and-reward systems, codes of conduct, types of moral conflicts, organizational influence, and industrial and corporate competitiveness [

64]. Compared with other corporate functions, marketing is more visible to the public because marketing forms direct connections between corporate organizations and customers. Similarly, the probability of a moral conflict in a company’s relationship with its customers is also higher than in other corporate activities.

One of the reviewers suggested that the ethics questions seem rather challenging to rate on the Likert scale. This issue will be assessed in a future study that controls for social desirability bias while considering ethics, morals, and misbehaviors. An additional limitation is the difficulty of providing sufficient theoretical grounds for the proposed hypotheses, because few studies have examined the relationship between ethical marketing practices and brand and product quality. This limitation made it difficult to measure the consumer-brand relationships and perceived quality of products such as raw materials. Studies on ethical aspects of marketing mix should be conducted in different context or areas. Furthermore, the measurement tools used in this work should be verified in future studies.