Sustained Participation in Virtual Communities from a Self-Determination Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustained Participation

2.2. Self-Determination Theory

2.3. Virtual Community Identification

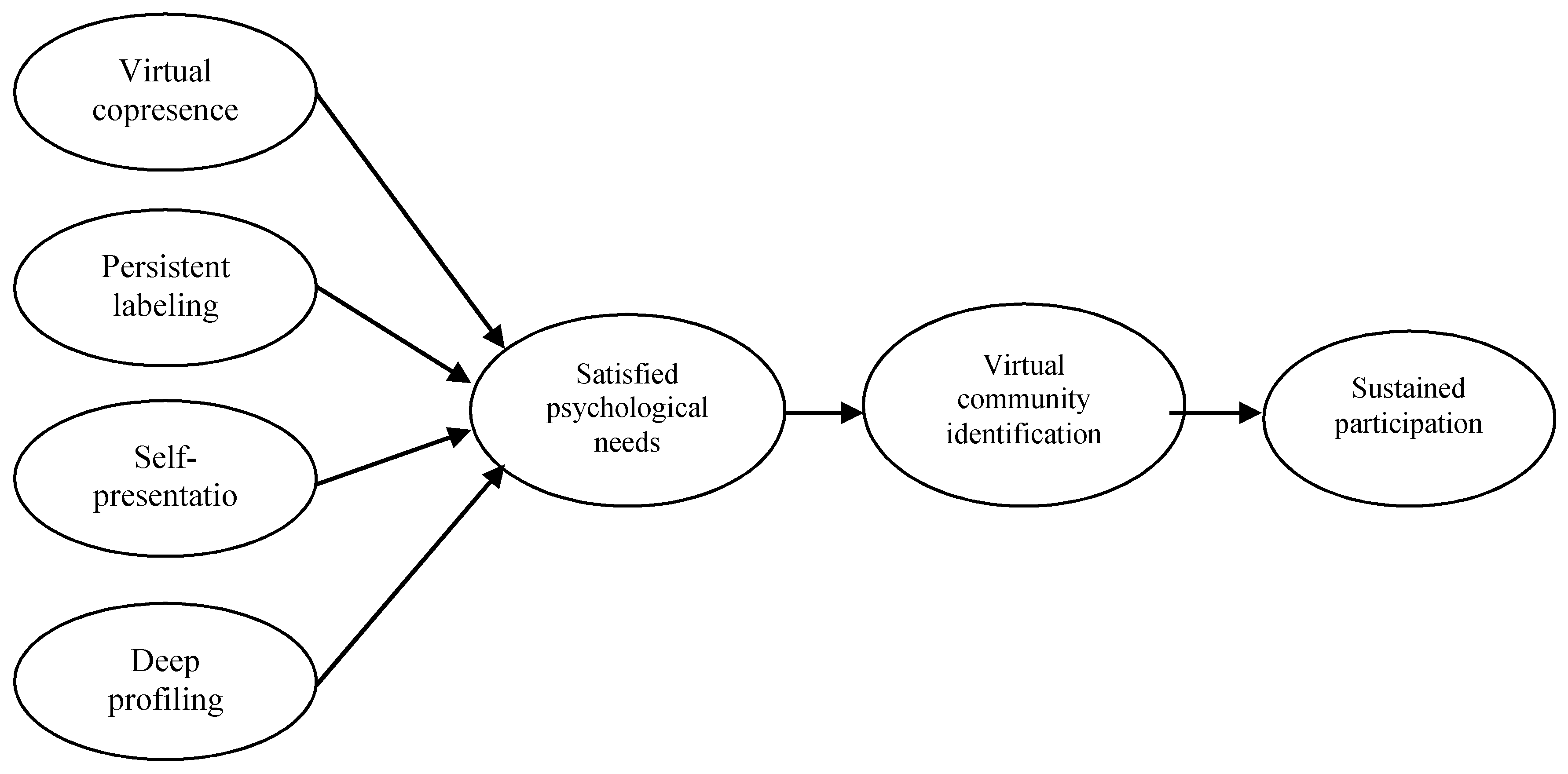

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

3.1. Community Artifacts and Satisfied Psychological Needs

3.2. Satisfied Psychological Needs and Virtual Community Identification

3.3. Virtual Community Identification and Sustained Participation

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Setting

4.2. Measurement

4.3. Data Collection

5. Results and Analyses

5.1. Reliability and Validity

5.2. Common Method Variance

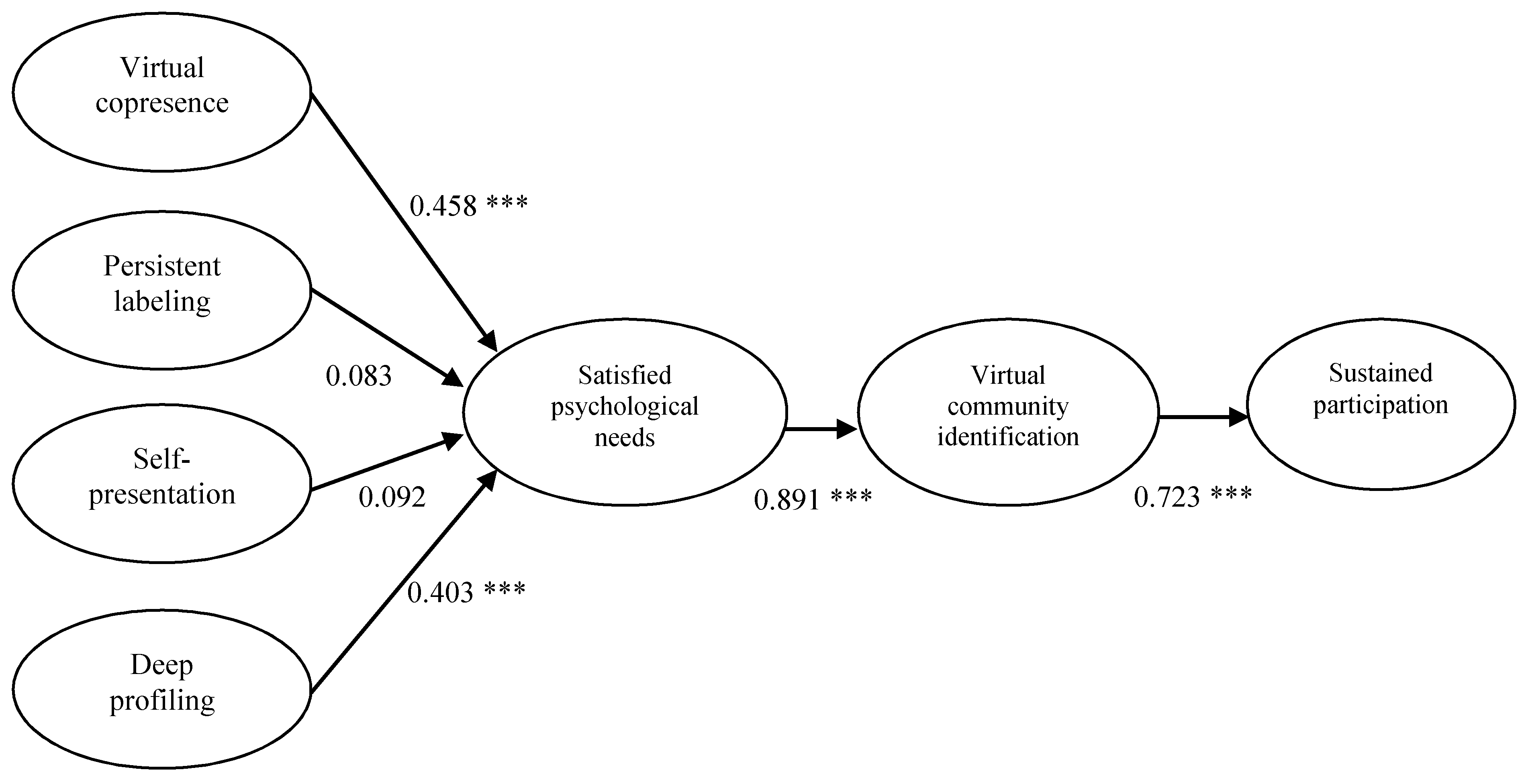

5.3. Hypothesis Tests—Douban (Interest-Based Community)

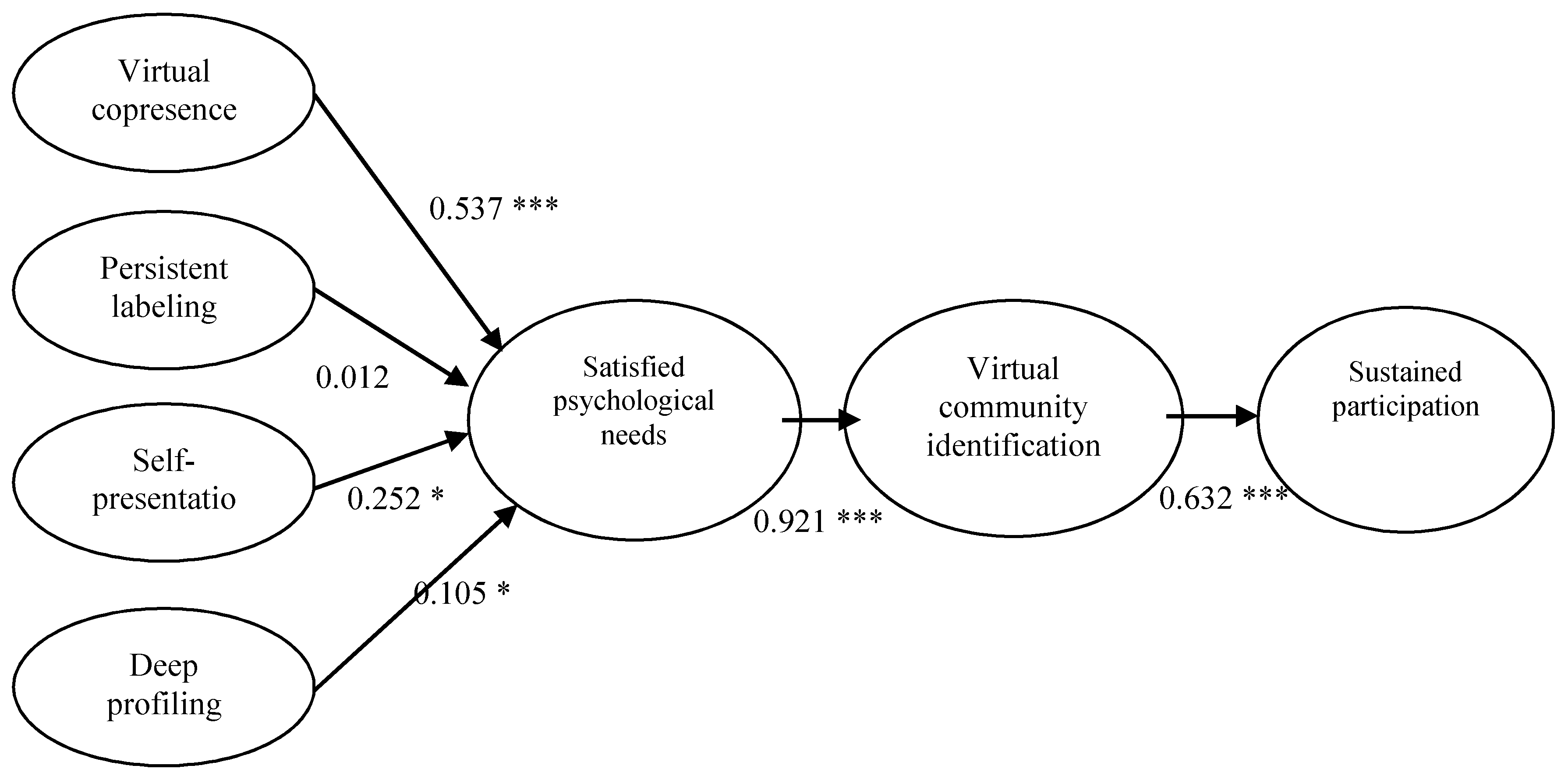

5.4. Hypothesis Tests—Sina Weibo(Relational-Based Community)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Directions Further Research

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Summary of Constructs and Their Measures

- Virtual copresence

- Q1_1 I find that people respond to my posts or private messages quickly.

- Q1_2 To what extent, if at all, did you ever have a sense of “being there with other people” in this community?

- Q1_3 To what extent, if at all, did you have a sense that you were together with other members in the virtual environment of this community?

- Persistent labeling

- Q2_1 I consistently use a single ID to communicate with other members in this community.

- Q2_2 I use more than one ID in this community (reversed). (Q2_2_0 = 8- Q2_2)

- Self-presentation

- Q3_1 I share my photos or other personal information with people from this community.

- Q3_2 I present information about myself in my profile.

- Q3_3 I use a special (or meaningful) signature in this community that differentiates me from others.

- Q3_4 I use a special (meaningful) name or nickname in this community that differentiates me from others.

- Deep profiling

- Q4_1 I think that other people search the archive to find out more about me.

- Q4_2 I think that other people have read my previous posts.

- Q4_3 I think that other people look at my profile to find out more about me.

- Satisfied psychological needs

- Q5_1 I am free to express my ideas and opinions in this community.

- Q5_2 I consider the people I am with in this community to be my friends.

- Q5_3 I have been able to learn interesting new skills in this community.

- Q5_4 Most days, I feel a sense of accomplishment from being in this community.

- Q5_5 People in this community care about me.

- Q5_6 I feel like I can pretty much be myself in this community.

- Q5_7 People in this community are pretty friendly towards me.

- Virtual community identification

- Q6_1 I identify with other members of the community.

- Q6_2 I am like other members of the community.

- Q6_3 I can reflect very well who I am.

- Q6_4 When I talk about this community I often want to say “We” instead of “They”.

- Q6_5 I dislike being a member of the community (reversed). (Q6_5_0 = 8 – Q6_5)

- Q6_6 I would rather belong to the other communities (reversed). (Q6_6_0 = 8 – Q6_6)

- Q6_7 I feel good about this community.

- Sustained participation

- Q9_1 I often help other people in this community who need help/information from other members.

- Q9_2 I take an active part in this community.

- Q9_3 I have contributed knowledge to this community.

- Q9_4 I have contributed by imparting knowledge to other members that resulted in the development of new insights for them.

References

- Bateman, P.J.; Gray, P.; Butler, B.S. The impact of community commitment on participation in online communities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valck, K.; Van Bruggen, G.H.; Wierenga, B. Virtual communities: A marketing perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 47, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, B.P.; Pearo, L.K. A social influence model of consumer participation in network- and small-group-based virtual communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.; Kim, U.G.; Butler, B.; Bock, G.W. Encouraging participation in virtual communities. Commun. ACM 2007, 50, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, G.P.A.; Hor-Meyll, L.F.; de Paula Pessôa, L.A.G. Influence of virtual communities in purchasing decisions-The participants’ perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-F. Determinants of successful virtual communities: Contribution from system characteristics and social factors. Inf. Manag. 2008, 5, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, S.S.; Li, D. Customer participation in virtual brand communities: The self-construal perspective. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Intentional social action in virtual communities. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Blazevic, V.; Wiertz, C.; Algesheimer, R. Communal service delivery: How customers benefit from participation in firm-hosted virtual P3 communities. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 12, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhang, J. Users’ continued participation behavior in social Q&A communities: A motivation perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, R.-Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, L.-H.; Wang, L. Investigating sustained participation in open design community in China: The antecedents of user loyalty. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazy, O.; Gellatly, I.; Brainin, E.; Nov, O. Motivation to share knowledge using wiki technology and moderating effect of role perceptions. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2362–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Hann, I.; Slaughter, S.A. Understanding the motivations, participation, and performance of open source software developers: A longitudinal study of the apache projects. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubia, O.; Stephen, A. Intrinsic vs. image-related utility in social media: Why do people contribute content to twitter? Mark. Sci. 2013, 32, 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Lu, H.P. Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Agarwal, R. Through a glass darkly: Information technology design, identity verification, and knowledge contribution in online communities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 42–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, A.; Khosravi, P.; Dong, L. Motivating users toward continued usage of information systems: Self-determination theory perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Understanding the sustained use of online health communities from a self-determination perspective. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2842–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishika, R.; Kumar, A.; Janakiraman, R.; Bezawada, R. The effect of customers’ social media participation on customer visit frequency and profitability: An empirical investigation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hahn, J.; De, P. Continued participation in online innovation communities: Does community response matter equally for everyone? Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 1112–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, R.R.; Chiang, K.P. Shoppers in cyberspace: Are they from venus or mars and does it matter? J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A. A nonlinear model of information-seeking behavior. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2004, 55, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lim, K.H. Understanding sustained participation in transactional virtual communities. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddibhotla, N.B.; Subramani, M.R. Contributing to public document repositories: A critical mass theory perspective. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.K. Motivation, governance, and the viability of hybrid forms in open source software development. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1000–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.A.; Spielmann, N.; Kahle, L.R.; Kim, C.-H. The subjective norms of sustainable consumption: A cross-cultural exploration. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barab, S.A.; Duffy, T.M. From practice fields to communities of practice. In Theoretical Foundations of Learning; Jonassen, D.H., Land, S.M., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Ju, Y.L.; Yen, C.-H.; Chang, C.-M. Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.E.; Donthu, N.; Macelroy, W.H.; Wydra, D. How to foster and sustain engagement in virtual communities. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 80–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Mondejar, R.; Chu, C.W.L. Accounting for the influence of overall justice on job performance: Integrating self-determination and social exchange theories. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The Handbook of Self-Determination Research, 1st ed.; University of Rochester Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elstak, M.N.; Bhatt, M.; Van Riel, C.B.M.; Pratt, M.G.; Berens, G.A.J.M. Organizational identification during a merger: the role of self-enhancement and uncertainty reduction motives during a major organizational change. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 32–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, R.; Lea, M. Panacea or panopticon? The hidden power in computer-mediated communication. Commun. Res. 1994, 21, 427–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social categorization, social identity and social comparison. In Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Tajfel, H., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N.; Kortekaas, P.; Ouwerkerk, J.W. Self-categorization, commitment to the group, and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. The Social Psychology of Group Cohesiveness: From Attraction to Social Identity; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Weinstein, N.; Murayama, K.; Lynch, M.F.; Ryan, R.M. The ideal self at play: The appeal of video games that let you be all you can be. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Partala, T. Psychological needs and virtual worlds: Case Second Life. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2011, 69, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On assimilating identities to the self: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization and integrity within cultures. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia, J.E. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 3, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luyckx, K.; Schwartz, S.J.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkis, T.E.M.; Goossens, L. The path from identity commitments to adjustment: Motivational underpinnings and mediating mechanisms. J. Couns. Dev. 2010, 88, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.E.; Levine, C. A critical examination of the ego identity status paradigm. Dev. Rev. 1988, 8, 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.; Condor, S.; Mathews, A.; Wade, G.; Williams, J. Explaining intergroup differentiation in an industrial organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1986, 59, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcalexander, J.H.; Schouten, J.W.; Koenig, H.F. Building brand community. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergami, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self-categorization, affective commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Neufeld, D. Understanding sustained participation in open source software projects. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 25, 9–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, H.-T.; Pai, P. Explaining members’ proactive participation in virtual communities. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2013, 71, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.; Hagel III, J. The Real Value of Online Communities. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Biocca, F.; Harms, C.; Burgoon, J.K. Toward a more robust theory and measure of social presence: Review and suggested criteria. Presence: Teleoperators Virtual 2003, 12, 456–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.; Steed, A.; Axelsson, A.S.; Heldal, I.; Abelin, Å.; Wideström, J.; Nilsson, A.; Slater, M. Collaborating in networked immersive spaces: As good as being there together? Comput. Graph. 2001, 25, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Gagné, M.; Leone, D.R.; Usunov, J.; Kornazheva, B.P. Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ilardi, B.C.; Leone, D.; Kasser, T.; Ryan, R.M. Employee and supervisor ratings of motivation: Main effects and discrepancies associated with job satisfaction and adjustment in a factory setting. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 1789–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T.; Davey, J.; Ryan, R.M. Motivation and employee-supervisor discrepancies in psychiatric vocational rehabilitation setting. Rehabil. Psychol. 1992, 37, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Luhtanen, R. Collective self-esteem and ingroup bias. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Constructs | Scale Sources | 7-Points Likert-Type Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental characteristics of virtual communities | Biocca et al. (2003) [54] Schroeder et al. (2001) [55] | 1-strongly disagree or never like that 7-strongly agree or always like that |

| Satisfied psychological needs | Deci et al. (2001) [56] Ilardi et al. (1993) [57] Kasser et al. (1992) [58] | 1-not accurate 7-very accurate |

| Virtual community identification | Brown et al. (1986) [47] Crocke & Luhtanen (1990) [59] Ellemers et al. (1999) [38] Rosenberg (1965) [60] | 1-not accurate 7-very accurate |

| Sustained participation | Wasko & Faraj (2005) [40] Koh et al. (2007) [4] | 1-strongly disagree 7-strongly agree |

| Overall Characteristics | Douban (N = 432) | Sina Weibo (N = 191) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| male | 160 (37%) | 78 (41%) |

| female | 272 (63%) | 113 (59%) |

| Age | ||

| 20 years and younger | 74 (17%) | 28 (15%) |

| 21–30 years | 331 (76%) | 124 (65%) |

| 31–40 years | 24 (6%) | 38 (20%) |

| 41–50 years | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Over 50 years | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Education | ||

| High school and lower | 29 (7%) | 4 (2%) |

| College | 56 (13%) | 7 (4%) |

| Undergraduate | 273 (63%) | 92 (48%) |

| Master and above | 74 (17%) | 88 (46%) |

| Annual Income (in thousand) | ||

| Less than 10 | 199 (46%) | 72 (38%) |

| 10–50 | 129 (30%) | 46 (24%) |

| 50–300 | 101 (23%) | 52 (27%) |

| Over 300 | 3 (1%) | 21 (11%) |

| Length of the Participation in the Community | ||

| 1–2 years | 166 (38%) | 79 (41%) |

| 2–3 years | 102 (24%) | 44 (23%) |

| Over 3 years | 164 (38%) | 68 (36%) |

| Constructs | Items | Douban (the Interest-Based Community) | Sina Weibo (the Relational-Based Community) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | Accumulated Variance | Factor Loading | Accumulated Variance | ||

| Sustained participation | Q7_1 | 0.747 | 71.164% | 0.721 | 69.193% |

| Q7_2 | 0.873 | 0.798 | |||

| Q7_3 | 0.884 | 0.918 | |||

| Q7_4 | 0.864 | 0.877 | |||

| Virtual community identification (Cognitive) | Q6_1 | 0.718 | 72.350% | 0.705 | 70.247% |

| Q6_2 | 0.794 | 0.724 | |||

| Q6_3 | 0.807 | 0.737 | |||

| Q6_4 | 0.784 | 0.623 | |||

| Virtual community identification (Affective) | Q6_5_0 | 0.871 | 0.660 | ||

| Q6_6_0 | 0.830 | 0.603 | |||

| Virtual community identification (Evaluative) | Q6_7 | 0.902 | 0.735 | ||

| Satisfied psychological needs (Relatedness) | Q5_5 | 0.863 | 75.592% | 0.828 | 74.974% |

| Q5_7 | 0.754 | 0.633 | |||

| Q5_2 | 0.663 | 0.802 | |||

| Satisfied psychological needs (Competence) | Q5_4 | 0.698 | 0.824 | ||

| Q5_3 | 0.910 | 0.866 | |||

| Satisfied psychological needs (Autonomy) | Q5_1 | 0.851 | 0.868 | ||

| Q5_6 | 0.811 | 0.877 | |||

| Virtual copresence | Q1_1 | 0.650 | 66.090% | 0.699 | 69.745% |

| Q1_2 | 0.872 | 0.874 | |||

| Q1_3 | 0.856 | 0.873 | |||

| Persistent labeling | Q2_1 | 0.723 | 0.927 | ||

| Q2_2_0 | 0.788 | 0.899 | |||

| Self-presentation | Q3_1 | 0.550 | 0.611 | ||

| Q3_2 | 0.523 | 0.597 | |||

| Q3_3 | 0.847 | 0.805 | |||

| Q3_4 | 0.829 | 0.808 | |||

| Deep profiling | Q4_1 | 0.814 | 0.831 | ||

| Q4_2 | 0.864 | 0.822 | |||

| Q4_3 | 0.857 | 0.834 | |||

| Constructs | N of Items | Douban | Sina Weibo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s α | Cronbach’s α | ||

| Sustained participation | 4 | 0.861 | 0.849 |

| Virtual community identification | 7 | 0.745 | 0.706 |

| Satisfied psychological needs | 7 | 0.826 | 0.717 |

| Environmental characteristics | 12 | 0.799 | 0.753 |

| Virtual copresence | 3 | 0.759 | 0.782 |

| Persistent labeling | 2 | 0.738 | 0.805 |

| Self-presentation | 4 | 0.721 | 0.715 |

| Deep profiling | 3 | 0.854 | 0.838 |

| Absolute Fit Index | Relative Fit Index | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | NFI | TLI | CFI |

| 728.324 | 374 | 1.947 | 0.047 | 0.896 | 0.871 | 0.876 | 0.924 | 0.935 |

| Constructs | Construct Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual copresence | 0.7881 | 0.5669 |

| Persistent labeling | 0.6297 | 0.5213 |

| Self-presentation | 0.7458 | 0.5010 |

| Deep profiling | 0.8555 | 0.6647 |

| Satisfied psychological needs | 0.8371 | 0.6342 |

| Virtual community identification | 0.6198 | 0.5031 |

| Sustained participation | 0.8323 | 0.5556 |

| Absolute Fit Index | Relative Fit Index | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | NFI | TLI | CFI |

| 699.405 | 377 | 1.855 | 0.067 | 0.887 | 0.862 | 0.858 | 0.879 | 0.899 |

| Constructs | Construct Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual copresence | 0.8051 | 0.5900 |

| Persistent labeling | 0.7887 | 0.6174 |

| Self-presentation | 0.7927 | 0.5051 |

| Deep profiling | 0.8494 | 0.6579 |

| Satisfied psychological needs | 0.7519 | 0.5038 |

| Virtual community identification | 0.6198 | 0.5031 |

| Sustained participation | 0.8895 | 0.6728 |

| Research Hypotheses | Path Description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1a. Community artifacts supporting for virtual copresence is positively related to satisfaction of psychological needs. | Virtual copresence → Satisfied psychological needs | Supported |

| H1b. Community artifacts supporting for persistent labeling is positively related to satisfaction of psychological needs. | Persistent labeling → Satisfied psychological needs | Not Supported |

| H1c. Community artifacts supporting for self-presentation is positively related to satisfaction of psychological needs. | Self-presentation → Satisfied psychological needs | Supported (relational-based community) Not supported (interest-based community) |

| H1d. Community artifacts supporting for deep profiling is positively related to satisfaction of psychological needs. | Deep profiling → Satisfied psychological needs | Supported |

| H2. Users’ satisfied psychological needs are positively related to their virtual community identification. | Satisfied psychological needs → Virtual community identification | Supported |

| H3. Virtual community identification is positively related to sustained participation behavior for users. | Virtual community identification → Sustained participation | Supported |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z. Sustained Participation in Virtual Communities from a Self-Determination Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236547

Zhang Z. Sustained Participation in Virtual Communities from a Self-Determination Perspective. Sustainability. 2019; 11(23):6547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236547

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhe. 2019. "Sustained Participation in Virtual Communities from a Self-Determination Perspective" Sustainability 11, no. 23: 6547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236547

APA StyleZhang, Z. (2019). Sustained Participation in Virtual Communities from a Self-Determination Perspective. Sustainability, 11(23), 6547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236547