Perceived Mental Benefit in Electronic Commerce: Development and Validation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

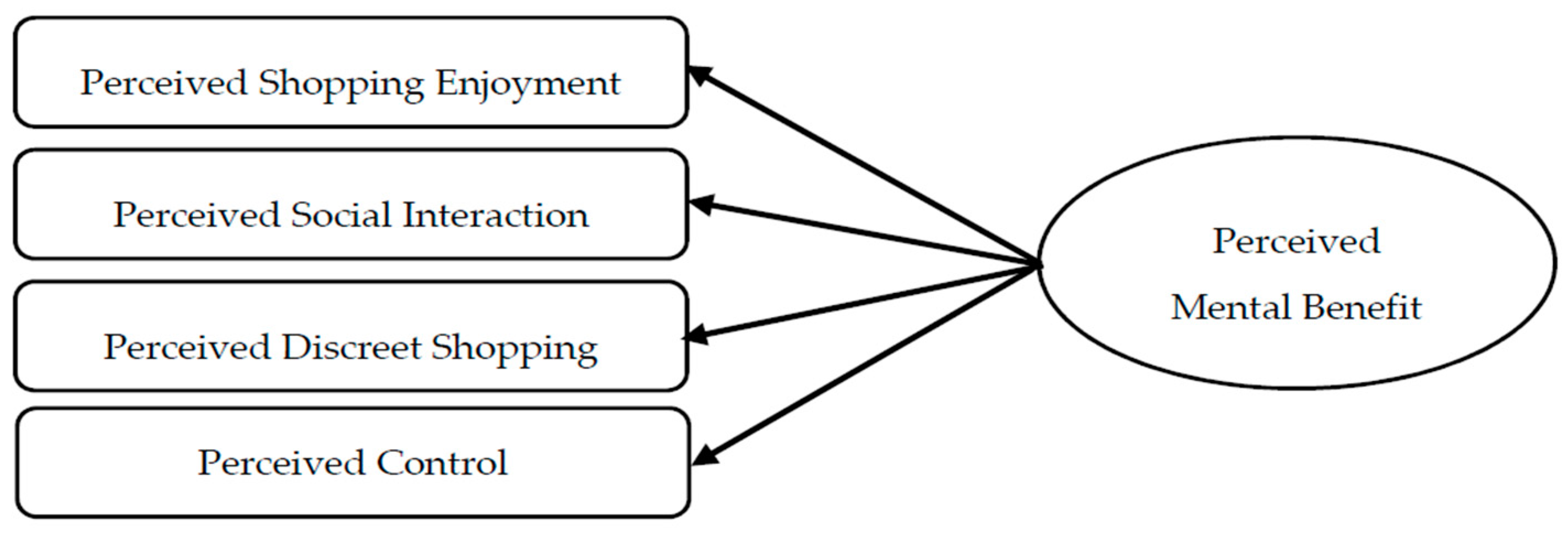

2.1. Perceived Mental Benefit

2.2. Theoretical Background

2.3. The Dimensions of Perceived Mental Benefit

2.3.1. Perceived Shopping Enjoyment (PEB)

2.3.2. Perceived Social Interaction (PSB)

2.3.3. Perceived Discreet Shopping (PDB)

2.3.4. Perceived Control (PCB)

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Scale Development and Validation

3.1.1. Item Generation

3.1.2. Initial Purification

3.1.3. Scale Refinement (Study 1)

3.1.4. Scale validity (Study 2)

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.3. Scale Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Item Generation

4.2. Initial Purification

4.3. Scale Refinement

4.3.1. EFA and Cronbach’s Alpha

- Although factor loading values greater than 0.5

- 0.5 ≤ KMO ≤ 1, and Bartlett test has the sig. < 0.05

- Cumulative of variance is higher than 50% with an Eigenvalue which must be greater than 1.0

- Construct 1 consists of six items, including PMB1, PMB2, PMB3, PMB4, PMB19, PMB24.

- Construct 2 consists of five items, including PMB11, PMB35, PMB36, PMB37, PMB38.

- Construct 3 consists of four items, including PMB5, PMB16, PMB27, PMB32.

- Construct 4 consists of four items, including PMB15, PMB28, PMB29, PMB30.

- Construct 5 consists of four items, including PMB21, PMB22, PMB25, PMB31.

- Construct 6 consists of four items, including PMB12, PMB13, PMB14, PMB18.

- Construct 7 consists of two items, including PMB9, PMB20.

- Construct 8 consists of two items, including PMB7, PMB34.

4.3.2. First-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.3.3. Assessment of the Validity of the Construct

4.4. The Scale Validity

4.4.1. Second-Order CFA

4.4.2. The Nomological Validity

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Y.; Fang, S.; Hwang, Y. Investigating Privacy and Information Disclosure Behavior in Social Electronic Commerce. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietnam eCommerce and Digital Economy Agency. Vietnam E-Commerce White Paper 2018. Available online: http://www.idea.gov.vn/file/c08520aa-0222-4c61-af72-12e0477151b6 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Forsythe, S.; Liu, C.; Shannon, D.; Gardner, L.C. Development of a scale to measure the perceived benefits and risks of online shopping. J. Interact. Mark. 2006, 20, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Khoa, B.T. A Study on the Chain of Cost—Values-Online Trust: Applications in Mobile Commerce in Vietnam. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. 2019, 14, 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, S.-H. E-Commerce Liability and Security Breaches in Mobile Payment for e-Business Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Kourouthanassis, P.E.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Explaining online shopping behavior with fsQCA: The role of cognitive and affective perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MBA Research and Curriculum Center. What’s the Motive? Buying Motives. In Leadership, Attitude, Performance: Making Learning Pay; Pendleton County Schools: Pendleton County, KY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N. An Integrative Theory of Patronage Preference and Behavior; College of Commerce and Business Administration, Bureau of Economic and Business Research, University of Illinois: Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L.; Goodman, M.; Brady, M.; Hansen, T. Marketing Management; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2019; Vol. 4th European Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Delafrooz, N.; Paim, L.H.; Khatibi, A. Understanding consumer’s internet purchase intention in Malaysia. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 2837–2846. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A. Impact of utilitarian and hedonic shopping values on individual’s perceived benefits and risks in online shopping. Int. Manag. Rev. 2011, 7, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Q.; Tran, X.; Misra, S.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R. Relationship between convenience, perceived value, and repurchase intention in online shopping in Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenheer, J.; Van Heerde, H.J.; Bijmolt, T.H.; Smidts, A. Do loyalty programs really enhance behavioral loyalty? An empirical analysis accounting for self-selecting members. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouni-Chaabane, A.; Volle, P. Perceived benefits of loyalty programs: Scale development and implications for relational strategies. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O. User experience in personalized online shopping: A fuzzy-set analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 1679–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Gellman, M. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, H.; Jung, J.; Kim, J.; Shim, S.W. Cross-cultural differences in perceived risk of online shopping. J. Interact. Advert. 2004, 4, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, Y. The effect of information satisfaction and relational benefit on consumer’s online shopping site commitment. Web Technol. Commer. Serv. Online 2008, 1, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Todd, P.A. Consumer reactions to electronic shopping on the World Wide Web. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 1996, 1, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Stern, B.B. The Roles of Emotion in Consumer Research. Adv. Consum. Res. 1999, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The role of emotions in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Khoa, B.T. Perceived mental benefits of online shopping. J. Sci. 2019, 14, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- VandenBos, G.R. APA Dictionary of Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T. Perspectives on consumer decision making: An integrated approach. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosunmola, A.; Adegbuyi, O.; Kehinde, O.; Agboola, M.; Olokundun, M. Percieved value dimensions on online shopping intention: The role of trust and culture. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Khoa, B.T. The Relationship between the Perceived Mental Benefits, Online Trust, and Personal Information Disclosure in Online Shopping. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. The role of anticipated emotions in purchase intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Kourouthanassis, P.E.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Sense and sensibility in personalized e-commerce: How emotions rebalance the purchase intentions of persuaded customers. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (book). Libr. J. 1990, 115, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, D.-M.; Leknes, S.; Kringelbach, M. Hedonic value. In Handbook of Value: Perspectives from Economics, Neuroscience, Philosophy, Psychology and Sociology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Play and intrinsic rewards. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; HarperPerennial: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, I.S. Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Hise, R.T. E-satisfaction: An initial examination. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Social commerce research: Definition, research themes and the trends. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A.; Black, W.C. A motivation-based shopper typology. J. Retail. 1985, 61, 78–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, P.H.; Bruce, G.D. Product Involvement as Leisure Behavior. Advances in Consumer Research 1984, 11, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Todd, P.A. Is there a future for retailing on the Internet. Electron. Mark. Consum. 1997, 1, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, S.E.; Ferrell, M.E. Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygostski, L. Pensée et langage. coll. In Terrains; Messidor: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wertsch, J.V. Culture, Communication, and Cognition: Vygotskian Perspectives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Hiltz, S.R. Factors that influence online relationship development in a knowledge sharing community. AMCIS 2003 Proc. 2003, 53, 410–417. [Google Scholar]

- Scheinkman, J.A. Social interactions. In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd ed.; Durlauf, S.N., Blume, L.E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moor, J.H. Towards a theory of privacy in the information age. ACM SIGCAS Comput. Soc. 1997, 27, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, H.T.; Moor, J.H. Privacy protection, control of information, and privacy-enhancing technologies. ACM SIGCAS Comput. Soc. 2001, 31, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, J.; Orbke, W.H.; Penn, M.C.; Pensabene, P.A.; Ray, C.R.; Rios, J.F.; Robinson, J.M.; Troxel, K.J. Method for Shipping a Package Privately to a Customer. U.S. Patent No 7,295,997, 13 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Bansal, R.; Bansal, A. Online shopping: A shining future. Int. J. Techno-Manag. Res. 2013, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, J.; Breaux, T.D.; Reidenberg, J.R.; Norton, T.B. A theory of vagueness and privacy risk perception. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 24th International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), Beijing, China, 12–16 September 2016; pp. 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R. Consumer Sexualities: Women and Sex Shopping; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.W. Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychol. Rev. 1959, 66, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E.J.; Saegert, S. Crowding and cognitive control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervin, L.A. The need to predict and control under conditions of threat. J. Personal. 1963, 31, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godek, J. Customization Decisions: The Effects of Perceived Control and Decomposition on Evaluations; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-opting customer competence. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, N.; Keinz, P.; Steger, C.J. Testing the value of customization: When do customers really prefer products tailored to their preferences? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Bearden, W.O.; Hardesty, D.M.; Rose, R.L. Consumer self-confidence: Refinements in conceptualization and measurement. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vietnam eCommerce and Digital Economy Agency. Vietnam E-Commerce White Paper 2019. Available online: http://www.idea.gov.vn/file/ef6314a6-709e-4d42-a2fa-b60457a66179 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Vietnam E-Commerce Association. Vietnam E-Commerce Index 2018, 2018; 1, 30–35.

- Lee, C.-H.; Wu, J.J. Consumer online flow experience: The relationship between utilitarian and hedonic value, satisfaction and unplanned purchase. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 2452–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, X. The effects of online trust-building mechanisms on trust and repurchase intentions: An empirical study on eBay. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 31, 666–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, R.K.; Sin, R.G. Personalization versus privacy: An empirical examination of the online consumer’s dilemma. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2005, 6, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastlick, M.A.; Feinberg, R.A. Shopping motives for mail catalog shopping. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 45, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Ghose, S. Segmenting consumers based on the benefits and risks of Internet shopping. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassarjian, H.H. Content analysis in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIver, J.; Carmines, E.G. Unidimensional Scaling; Sage Publication: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, P.Y. Reexamining a model for evaluating information center success using a structural equation modeling approach. Decis. Sci. 1997, 28, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Introduction to Psychological Measurement; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Rahman, Z. Measuring customer social participation in online travel communities: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2017, 8, 432–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Amendah, E.; Lee, Y.; Hyun, H. M-payment service: Interplay of perceived risk, benefit, and trust in service adoption. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2019, 29, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T.A.; Sharma, S. Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, M.J.; Reynolds, K.E. Hedonic shopping motivations. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebrianti, W. Web attractiveness, hedonic shopping value and online buying decision. Pertanika Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2016, 10, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Pla-García, C.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Rodríguez-Ardura, I. Hedonic motivations in online consumption behaviour. Int. J. Bus. Environ. 2016, 8, 121–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Hui, P.; Khan, M.K.; Yan, C.; Akram, Z. Factors Affecting Online Impulse Buying: Evidence from Chinese Social Commerce Environment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thong, V. 60% of Vietnamese Network Users ‘Entertain’ by Shopping. Available online: https://vnexpress.net/kinh-doanh/60-nguoi-dung-mang-viet-nam-giai-tri-bang-cach-mua-sam-3632371.html (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Onlymyhealth.com. Can Shopping Help Relieve Stress? Here’s the Answer! Available online: https://www.onlymyhealth.com/can-shopping-help-relieve-stress-heres-answer-1300184407 (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- To, P.-L.; Liao, C.; Lin, T.-H. Shopping motivations on Internet: A study based on utilitarian and hedonic value. Technovation 2007, 27, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentalhealth. Friendship and Mental Health. Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/f/friendship-and-mental-health (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- To, P.-L.; Sung, E.-P. Internet shopping: A study based on hedonic value and flow theory. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2015, 9, 2221–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Tynan, D. Personalization Is a Priority for Retailers, but Can Online Vendors Deliver? Available online: https://www.adweek.com/digital/personalization-is-a-priority-for-retailers-online-and-off-but-its-harder-than-it-looks-in-an-off-the-shelf-world/ (accessed on 12 June 2019).

| Demension | Element | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Utilitarian | Cost-saving | Spend less and save money |

| Convenience | To reduce choices and save time and effort | |

| Hedonic | Exploration | To discover and try out new products sold by the company |

| Entertainment | To enjoy, to have fun with shopping | |

| Symbolic | Recognization | To have a unique state, to feel different and to be treated better |

| Social | Belong to a group of common values |

| Item Generation and Initial Purification | Scale Refinement | Scale Validity |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Characteristics | Study 1 (n = 276) | Study 2 (n = 439) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |||

| Gender | Male | 137 | 50.4 | Male | 217 | 49.4 |

| Female | 139 | 49.6 | Female | 222 | 50.6 | |

| Level/Age | First year | 32 | 11.6 | Below 20 | 99 | 22.6 |

| Second year | 79 | 28.6 | 20–24 | 64 | 14.6 | |

| Third year | 94 | 34.1 | 25–29 | 124 | 28.2 | |

| Fourth year | 67 | 24.3 | 30–34 | 89 | 20.3 | |

| Other | 4 | 1.4 | Above 34 | 63 | 14.4 | |

| Major/Occupation | Business Administration | 140 | 50.7 | Student | 142 | 32.3 |

| IT | 52 | 49.2 | Lecturer | 71 | 16.2 | |

| Office worker | 226 | 51.5 | ||||

| Code | The Statement About the Mental Benefit of E-commerce |

|---|---|

| PMB01 | Feel like I live in my universe |

| PMB02 | When I am in a depressed mood, shopping online will help me feel better |

| PMB03 | For me, online shopping is a way to reduce stress |

| PMB04 | I shop when I want to treat myself in an unique way |

| PMB05 | I feel connected to others when I shop online |

| PMB06 | I like to shop for others because when they feel good, I feel good * |

| PMB07 | I love shopping for my friends and family ** |

| PMB08 | I love shopping to find the perfect gift for someone * |

| PMB09 | Shopping with others creates an engaging experience ** |

| PMB10 | I go shopping with friends or family to socialize * |

| PMB11 | Online shopping ensures privacy on the buying process |

| PMB12 | I engage in pure online consumption to enjoy the shopping process. ** |

| PMB13 | Visiting this e-commerce site is intrinsically interesting. ** |

| PMB14 | The e-commerce site is a great platform where I can satisfy the need of expressing myself. ** |

| PMB15 | The e-commerce site that allows me to control my online shopping process |

| PMB16 | Exchange information with friends |

| PMB17 | Share your experiences with others * |

| PMB18 | I find stimulating consumption online. ** |

| PMB19 | I felt perceived adventure while shopping online (whether I ended up buying any or not). |

| PMB20 | Online shopping allows me to forget about work. ** |

| PMB21 | Engaging in online consumption takes me out of severe problems. ** |

| PMB22 | Participating in online shopping makes me forget everything ** |

| PMB23 | I love browsing e-commerce sites and finally, shopping online is not just for the last thing. * |

| PMB24 | Compared to other things I can do, the time to make online consumption is exciting. |

| PMB25 | To kill time, I participated in online consumption. ** |

| PMB26 | I participate in online consumption in my free time for entertainment. * |

| PMB27 | Online shopping is a great way to develop friendships with other internet shoppers. |

| PMB28 | I have the option to participate, express myself, and leave my mark. |

| PMB29 | I am also involved in the entire consumer experience by posting ideas to create the product. |

| PMB30 | The unique thing about e-commerce is to give me the ability to design everything |

| PMB31 | Online shopping helps me to satisfy my own need ** |

| PMB32 | I like reviewing content on e-commerce sites to check other customers’ reviews and opinions. |

| PMB33 | I want to be up to date with the latest consumer preferences. * |

| PMB34 | I like to learn on the e-commerce site about ideas and things that may interest me. ** |

| PMB35 | I do not mind if I do not buy anything after asking for product information on e-commerce sites. |

| PMB36 | When shopping online, I am not ashamed to buy sensitive goods/services. |

| PMB37 | I feel free to search for information when shopping online without anyone knowing. |

| PMB38 | I am not afraid to purchase discounted products/services on e-commerce sites. |

| No. | KMO | Sig | Eigen Value | Variance Explained | Construct | The Eliminated Items | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.895 | 0.00 | 1.036 | 64.022 | 11 | PMB26 | The factor loadings value < 0.5 |

| 2 | 0.998 | 0.00 | 1.019 | 65.250 | 11 | PMB8 | |

| 3 | 0.900 | 0.00 | 1.006 | 66.707 | 11 | PMB23 | |

| 4 | 0.903 | 0.00 | 1.003 | 67.932 | 11 | PMB6 | |

| 5 | 0.905 | 0.00 | 1.003 | 69.637 | 11 | PMB10, PMB17, PMB33 | Only one item |

| 6 | 0.910 | 0.00 | 1.066 | 65.693 | 8 | - | - |

| No. | Construct | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | The Total Correlation Coefficient (minimum) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Construct 1 | 6 | 0.883 | 0.671 | Reliability |

| 2 | Construct 2 | 5 | 0.944 | 0.805 | |

| 3 | Construct 3 | 4 | 0.906 | 0.654 | |

| 4 | Construct 4 | 4 | 0.903 | 0.758 | |

| 5 | Construct 5 | 5 | 0.577 | 0.297 | Unreliability |

| 6 | Construct 6 | 4 | 0.530 | 0.274 | |

| 7 | Construct 7 | 2 | −0.228 | −0.103 | |

| 8 | Construct 8 | 2 | 0.222 | 0.125 |

| Code | The Statement About the Mental Benefit of E-commerce | Name | New Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMB01 | Feel like I live in my universe | Perceived shopping enjoyment | PEB1 |

| PMB02 | When I’m in a depressed mood, shopping online will help me feel better | PEB2 | |

| PMB03 | For me, online shopping is a way to reduce stress | PEB3 | |

| PMB04 | I shop when I want to treat myself in an unique way | PEB4 | |

| PMB19 | I felt perceived adventure while shopping online (whether I ended up buying any or not). | PEB5 | |

| PMB24 | Compared to other things I can do, the time to make online consumption is exciting. | PEB6 | |

| PMB11 | Online shopping ensures privacy on the buying process | Perceived discreet shopping | PDB1 |

| PMB35 | I do not mind if I do not buy anything after asking for product information on e-commerce sites. | PDB2 | |

| PMB36 | When shopping online, I am not ashamed to buy sensitive goods/services. | PDB3 | |

| PMB37 | I feel free to search for information when shopping online without anyone knowing. | PDB4 | |

| PMB38 | I am not afraid to purchase discounted products/services on e-commerce sites. | PDB5 | |

| PMB05 | I feel connected to others when I shop online | Perceived social interaction | PSB1 |

| PMB16 | Exchange information with friends | PSB2 | |

| PMB27 | Online shopping is a great way to develop friendships with other internet shoppers. | PSB3 | |

| PMB32 | I like reviewing content on e-commerce sites to check other customers’ reviews and opinions. | PSB4 | |

| PMB15 | E-commerce site that allows me to control my online shopping process | Perceived control | PCB1 |

| PMB28 | I have the option to participate, express myself, and leave my mark. | PCB3 | |

| PMB29 | I am also involved in the entire consumer experience by posting ideas to create the product. | PCB3 | |

| PMB30 | The unique thing about e-commerce is to give me the ability to design everything | PCB4 |

| Construct | Item | Standardized (λi) | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived discreet shopping | PDB1 | 0.94 | 0.945 | 0.775 |

| PDB2 | 0.891 | |||

| PDB3 | 0.881 | |||

| PDB4 | 0.864 | |||

| PDB5 | 0.821 | |||

| Perceived shopping enjoyment | PEB1 | 0.785 | 0.884 | 0.559 |

| PEB2 | 0.737 | |||

| PEB3 | 0.724 | |||

| PEB4 | 0.743 | |||

| PEB5 | 0.737 | |||

| PEB6 | 0.759 | |||

| Perceived social interaction | PSB1 | 0.815 | 0.918 | 0.741 |

| PSB2 | 0.689 | |||

| PSB3 | 0.984 | |||

| PSB4 | 0.926 | |||

| Perceived control | PCB1 | 0.807 | 0.905 | 0.704 |

| PCB2 | 0.854 | |||

| PCB3 | 0.828 | |||

| PCB4 | 0.866 | |||

| Chi-square = 181.752; df = 146; CMIN/df = 1.245 | GFI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

| 0.937 | 0.991 | 0.990 | 0.03 |

| R | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB | <--> | PEB | 0.644 | 0.046 | 7.70 | 0.000 |

| PDB | <--> | PSB | 0.606 | 0.048 | 8.20 | 0.000 |

| PDB | <--> | PCB | 0.676 | 0.045 | 7.28 | 0.000 |

| PEB | <--> | PSB | 0.57 | 0.050 | 8.66 | 0.000 |

| PEB | <--> | PCB | 0.631 | 0.047 | 7.87 | 0.000 |

| PSB | <--> | PCB | 0.521 | 0.052 | 9.29 | 0.000 |

| Construct | Item | λi of First-Order | λi of Second-Order | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived discreet shopping | PDB1 | 0.910 | 0.589 | 0.938 | 0.939 | 0.755 |

| PDB2 | 0.875 | |||||

| PDB3 | 0.881 | |||||

| PDB4 | 0.864 | |||||

| PDB5 | 0.811 | |||||

| Perceived shopping enjoyment | PEB1 | 0.772 | 0.772 | 0.877 | 0.877 | 0.544 |

| PEB2 | 0.751 | |||||

| PEB3 | 0.743 | |||||

| PEB4 | 0.741 | |||||

| PEB5 | 0.708 | |||||

| PEB6 | 0.708 | |||||

| Perceived social interaction | PSB1 | 0.719 | 0.593 | 0.855 | 0.862 | 0.612 |

| PSB2 | 0.682 | |||||

| PSB3 | 0.912 | |||||

| PSB4 | 0.796 | |||||

| Perceived control | PCB1 | 0.752 | 0.650 | 0.860 | 0.861 | 0.607 |

| PCB2 | 0.781 | |||||

| PCB3 | 0.809 | |||||

| PCB4 | 0.773 | |||||

| KMO | Eigenvalues | Total variance extracted | Sig. Bartlett’s test | |||

| 0.911 | 1.626 | 63.179 | 0.000 | |||

| Chi-square = 231.883; df = 148 | CMIN/df | GFI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

| 1.567 | 0.950 | 0.983 | 0.981 | 0.036 | ||

| Construct | Item | Standardized | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonic value (HV) | HV1 | 0.854 | 0.913 | 0.726 |

| HV2 | 0.817 | |||

| HV3 | 0.922 | |||

| HV4 | 0.81 | |||

| Online trust (OT) | OT1 | 0.843 | 0.890 | 0.618 |

| OT2 | 0.734 | |||

| OT3 | 0.795 | |||

| OT4 | 0.822 | |||

| OT5 | 0.731 | |||

| Chi-square = 452.148; df = 335. CMIN/df = 1.350 | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

| 0.932 | 0.984 | 0.985 | 0.028 |

| OT | HV | PDB | PEB | PSB | PCB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OT | 1 | |||||

| HV | 0.519 | 1 | ||||

| PDB | 0.435 | 0.636 | 1 | |||

| PEB | 0.680 | 0.496 | 0.419 | 1 | ||

| PSB | 0.684 | 0.346 | 0.322 | 0.519 | 1 | |

| PCB | 0.406 | 0.687 | 0.469 | 0.486 | 0.328 | 1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, M.H.; Khoa, B.T. Perceived Mental Benefit in Electronic Commerce: Development and Validation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236587

Nguyen MH, Khoa BT. Perceived Mental Benefit in Electronic Commerce: Development and Validation. Sustainability. 2019; 11(23):6587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236587

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Minh Ha, and Bui Thanh Khoa. 2019. "Perceived Mental Benefit in Electronic Commerce: Development and Validation" Sustainability 11, no. 23: 6587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236587

APA StyleNguyen, M. H., & Khoa, B. T. (2019). Perceived Mental Benefit in Electronic Commerce: Development and Validation. Sustainability, 11(23), 6587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236587