Abstract

Among many solutions that can boost company innovativeness, co-creation is mentioned in the literature as one of them. This paper reports the findings of a pilot study conducted in China, Georgia, Poland, Romania, and Sri Lanka. The aim of the article is to find differences and similarities among respondents from different countries considering their attitude towards the process of co-creation. To gather primary data, a field survey method was adopted with a structured questionnaire. The target group of the survey consisted of university students, aged between 22 to 23 years old, who, by virtue of their psycho-physical characteristics, are more eager to share their experience and engage in various activities. A questionnaire-based survey was conducted from June to December 2016 among 500 university students. Despite the limited experience of respondents in co-creation, replies indicate their willingness, openness, and positive attitude towards co-creation.

1. Introduction

Co-creation is a term encountered more frequently in literature with reference to different disciplinary fields, such as business, design, marketing [1,2], management [3], and business networks [4]. The interest in co-creation is on the rise, which is the result of transformations in the enterprise environment. While considering co-creation, significant changes include the redefinition of the role of a customer and the growing awareness that the emerging changes related to product variety or the search for innovative solutions require quick and efficient reactions [5]. The prospect of changes related to the fourth industrial revolution makes it evident [6]. Furthermore, the role of a customer as a market participant has been evolving from a market recipient to its co-creator [2,7]. It is the effect of consumer trends changing at an increasingly quicker pace, including modifications in customer behavior. A contemporary consumer is aware, educated, self-assured, and seeks new experiences [8,9]. What is more, customers are more collaborative and considerably more adroit than at any other time in history [10,11]. The process of co-creation enables stakeholders to learn opinions and to take into account the feelings of participants in relation to company products [12]. The company can use four different strategies in order to cooperate with the customer. Those strategies are collaborating, tinkering, co-designing, and submitting [13]. Pilar and Ihl proposed wider dimensions based on topology of methods for customer co-creation. Also, they proposed three main characteristics: first, the stage in the innovations process; second, the degree of collaboration; and third, the degree of freedom [14]. Consumer knowledge is demonstrated in the increase of consumers’ environmental awareness, which is expressed in reduced consumption and a more conscious choice of products and sorting waste from such goods.

The important changes from a company’s point of view are related to the fact that contemporary customers are interested in what a company does and how products are created. They also wish to influence company decisions or co-create its products. In this regard, the customer can be considered as a partial employee and takes the role of prosumer, which means that he or she consumes the product that was co-created [15,16]. This customer is well-informed, more collaborative, and considerably more adroit [11,17]. Prahland and Ramaswamy believe that the reason the customer gets involved in co-creation is due to a limited satisfaction with products despite their substantial variability [18], while Jaworski and Kohli are convinced that the customer is looking for a dialogue with the firm [19].

For a company, the co-creation of products with the customer becomes an effective tool for innovative company solutions [5]. The traditional view of customers in the innovation process is that they are either passive or "speaking only when spoken to" [20] in the course of market research or concept testing. This point of view has recently been challenged by many researchers who note that there is also a more active role of customers in innovation processes [21]. Development through implementation of co-creation enables reaching a competitive advantage. The sources of this advantage include gains in effectiveness and productivity gains through efficiency [16]. Moreover, one of the gains in effectiveness of the co-created product is increased innovativeness [22]. Thanks to consumer reviews, the company can improve the quality of their product. Co-creation also enables the company to provide products that are tailored to customer’s individual needs [16,23], so another benefit of applying co-creation is better understanding of those needs [24]. Moreover, understanding customer needs and then developing products to meet those needs are the basis for successful innovation [25]. Nowadays, companies endeavour to be more profitable and to achieve growth through innovation. This causes an increasing number of failed products. In order to minimize the risk of failures, the company has to cooperate [13]. Cooperation with the customer is useful to generate information about new product development. This information might be gathered in three different ways: "listen into" the customer domain, "ask" customers, and "build" with customers [14]. All those modes are used while co-creating a new product with the customer. A company can also apply co-creation as a new way of establishing relationships with clients by including them in the business [26].

Furthermore, studies show that there is a positive relationship between the value of co-creation and the customer’s trust [27], loyalty [28], or satisfaction [16,24,29]. Trust adds value to customers and influences their loyalty towards the company [28,30]. The literature also features a model of co-creation comprising participation, co-creation, satisfaction, and trust, where trust and satisfaction are analysed as results [12]. Therefore, the process of co-creation is beneficial to both sides [31].

It is indicated that co-creation is a response to a challenge caused by innovation. However, it is only possible if all the collective potential of groups can lead to changes wherein every participant is empowered [1]. Other studies demonstrate that involved customers are frequently willing to cooperate and share their knowledge and experiences. However, they are unable to do so since they encounter numerous economic and technological limitations as well as problems related to the lack of knowledge about the process of co-creation [15]. It is stressed in the literature that the essential characteristics of a co-creating customer include their experiences, degree of involvement, and the type of interaction between the company and the customer [32]. The fact that the customer creates products for himself and that he is an essential subject of co-creation is an important element of this process [33].

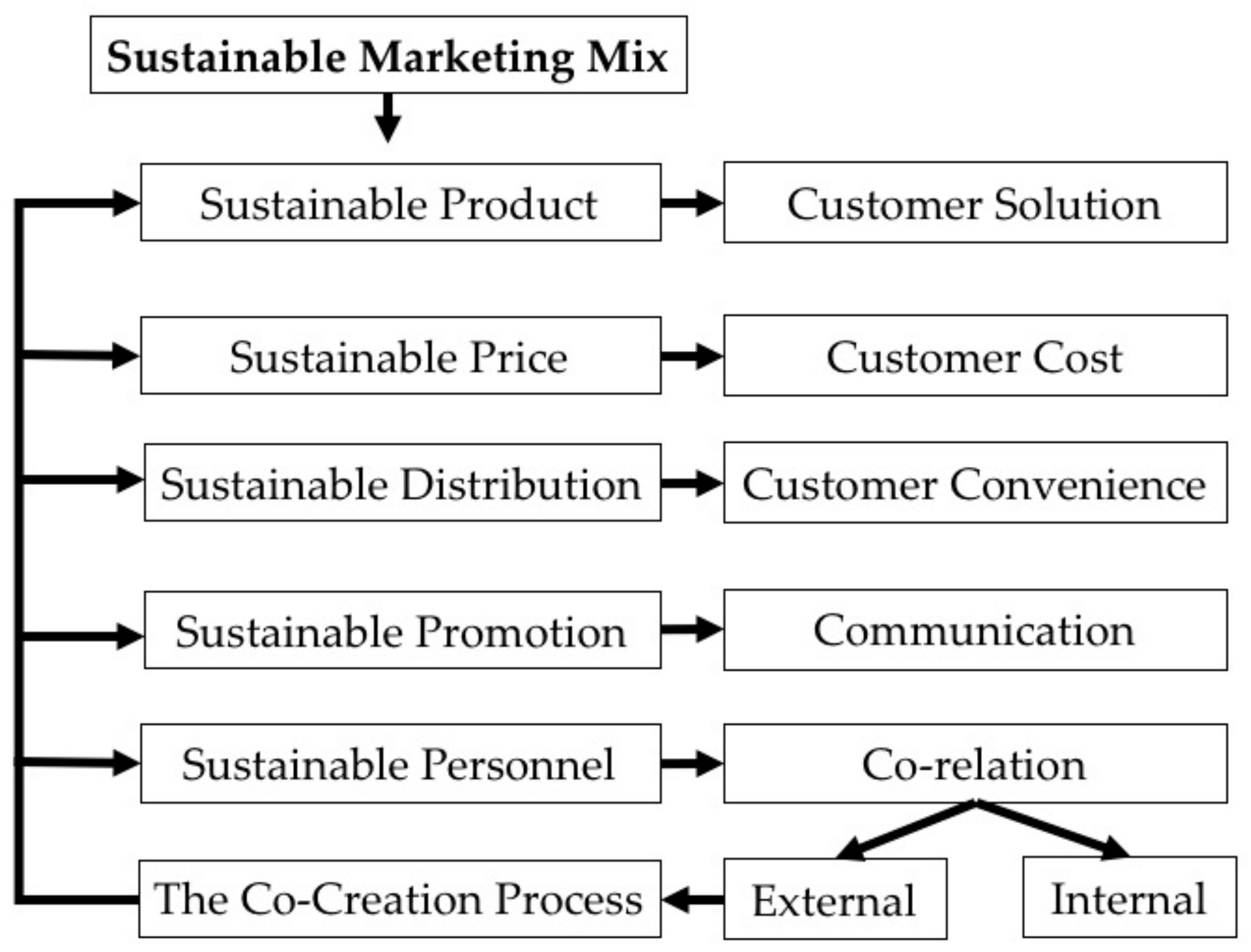

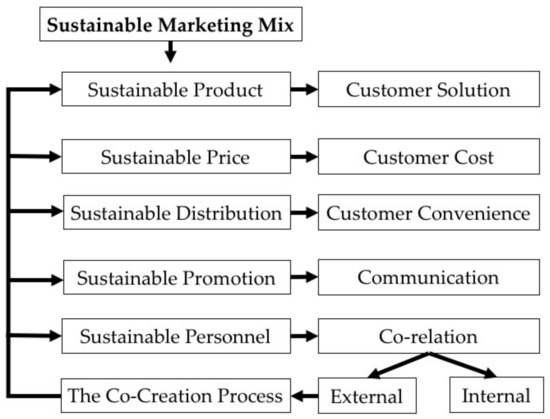

Cooperation with customers gives the company an opportunity to create products in accordance with customer expectations. Such activity fits with the concept of sustainable marketing tools. In this concept, the traditional marketing mix (product, price, place, promotion, people) is transformed into sustainable 5C (costumer solution, customer cost, convenience, communication, co-relations). It means that by adopting the concept of the sustainable marketing mix, the company simultaneously accepts customers as the co-creators of the product and other company activities [34]. Therefore, the concept of product co-creation constitutes a new, innovative tool for activities of a sustainable nature, including sustainable organization development. A model that shows the relationship between sustainable marketing and co-creation is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Relationship between co-creation and sustainable marketing. Source: own study.

As shown in Figure 1, it can be concluded that there is a strong conceptual relationship between the sustainable marketing mix and the co-creation process. According to this concept, co-creation becomes an intermediary component of sustainable business development in terms of sustainable product, sustainable price, sustainable distribution, sustainable promotion, and sustainable personnel. Thus, involvement in co-creation has a significant impact on achieving business sustainability objectives and continuous development of a company.

Nevertheless, it is worth remembering that the analysis of literature on the subject demonstrates a strong relationship between the success of co-created products and the producers’ ability to win suitable, knowledgeable participants in the co-creation process [35,36]. Furthermore, what is extremely important in the process of co-creation is for the customer to be involved in all phases, starting from the initial phase of an idea for product or service development. The difficulty of the process may involve synchronization of the activities of all the parties since success depends on proper operation of the involved entities [37,38].

The process of co-creation has more and more frequently become a research subject; however, research thus far has not taken into consideration the participation of respondents from several countries while simultaneously accounting for their attitude towards the co-creation process and previous experiences in this regard. Empirical evidence of research on attitude towards co-creation among respondents from different countries is scarce. Therefore, the significance of this study is based on the cross-country analysis. At the same time, this study fills in the research gap concerning attitudes towards co-creation among university students from different countries. The main contribution of this study is to promote co-creation as an innovative way to develop companies situated in different parts of the world. In this aspect, development might be reached by production of high-quality, co-created, innovative output, while co-creation is understood as an entrepreneurial, forward-thinking initiative [39]. Therefore, this paper aims to discover differences and similarities among respondents from different countries (China, Georgia, Poland, Romania, Sri Lanka) considering their attitude towards the process of co-creation. A person’s attitude is defined in the literature as a constant, cognitive evaluation of feelings or activities that are intended to show the likes or dislikes of specific concepts [40]. Therefore, the authors understand ‘attitude’ as an inborn quality of learning, thanks to which one can cohesively perceive the things with which they agree or not [41]. The development of an individual’s positive attitude towards a selected subject, for instance co-creation, depends on whether participation in that process may bring benefits or positive results. Conversely, if the expected result is not favourable, a negative attitude to co-creation emerges [42].

In light of the obtained research results, it can be concluded that the emergence of an opportunity or an invitation to participate in the co-creation process is sufficient to ensure such participation and to develop a positive approach to co-creation. The respondents found that the very idea of working with a company or an opportunity to generate ideas for brands is fantastic and challenging. For companies, this is an indicator that if they wish to involve young people in the process of co-creation, it is enough to invite them, and the probability of a positive reaction is high.

2. Materials and Methods

This pilot research study was designed to collect the primary data and analyse the same in line with the objectives of the study to arrive at conclusions. The field survey method was applied to collect primary data from university students from China, Georgia, Poland, Romania, and Sri Lanka through a structured research questionnaire. In order to achieve primary research objectives, the authors selected the above-mentioned countries based on accessibility. The survey was conducted from June until December 2016 among 500 respondents, and the response rate was 100%. This research group represents those who, by virtue of their psycho-physical characteristics, are more eager to share their experiences and engage in various activities. Although all stakeholders should be involved in the co-creation process, current research has focused on the role of students in this process and how the place of residence affects their attitude towards co-creation. Taking into account that gaining customer participation is a key factor in the success of implementing co-creation as an innovative way to develop an organization, this pilot research might be useful to acquire the knowledge on factors that would encourage them to participate in co-creation.

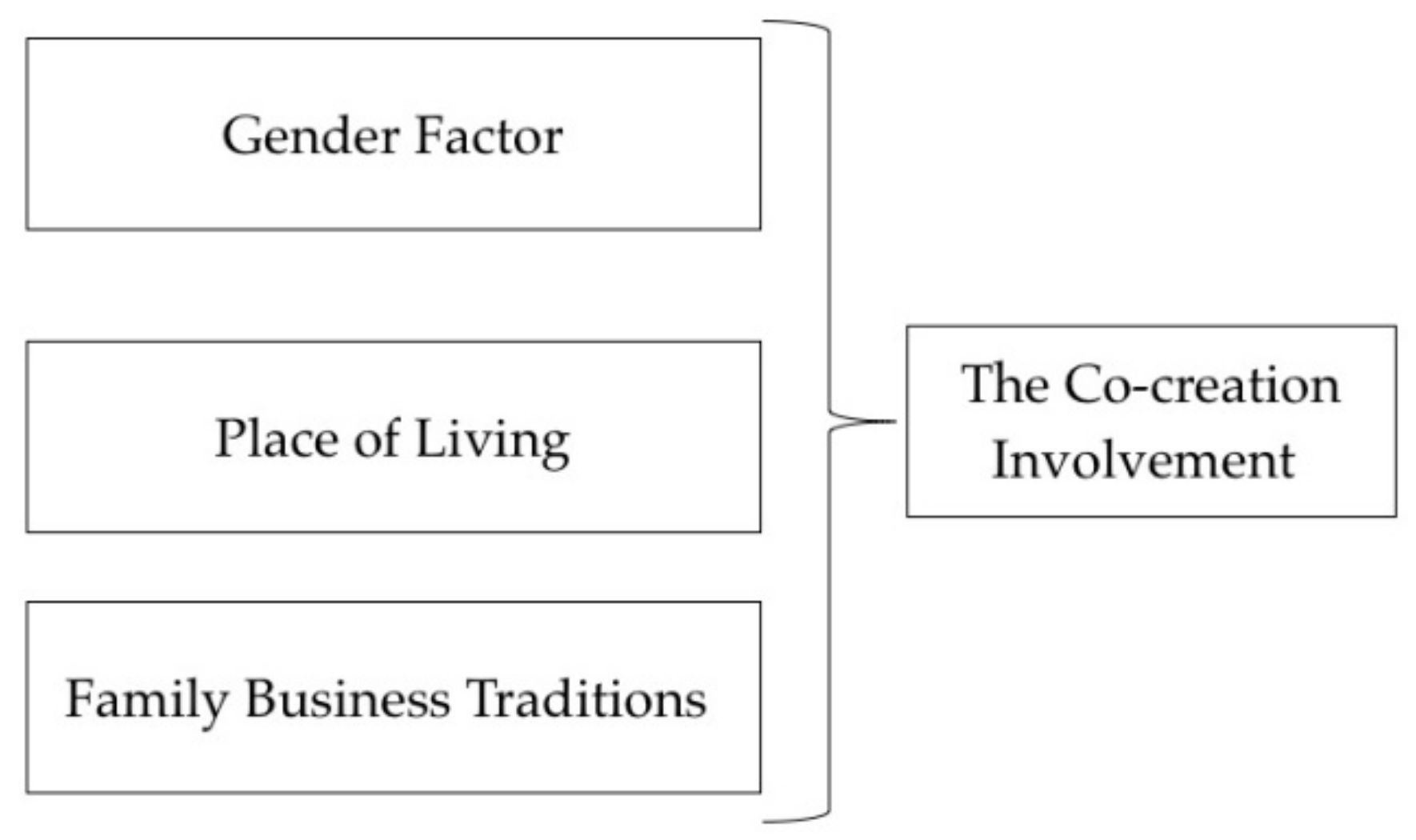

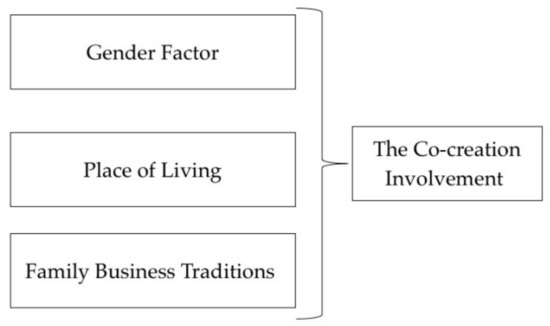

Three conceptual frameworks were created in order to examine the research objectives. Conceptual framework 1 (CF1) is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework 1. Source: own study.

According to CF1, the research objective is to examine the involvement in co-creation based on social–demographic characteristics such as gender, place of living, and family business traditions.

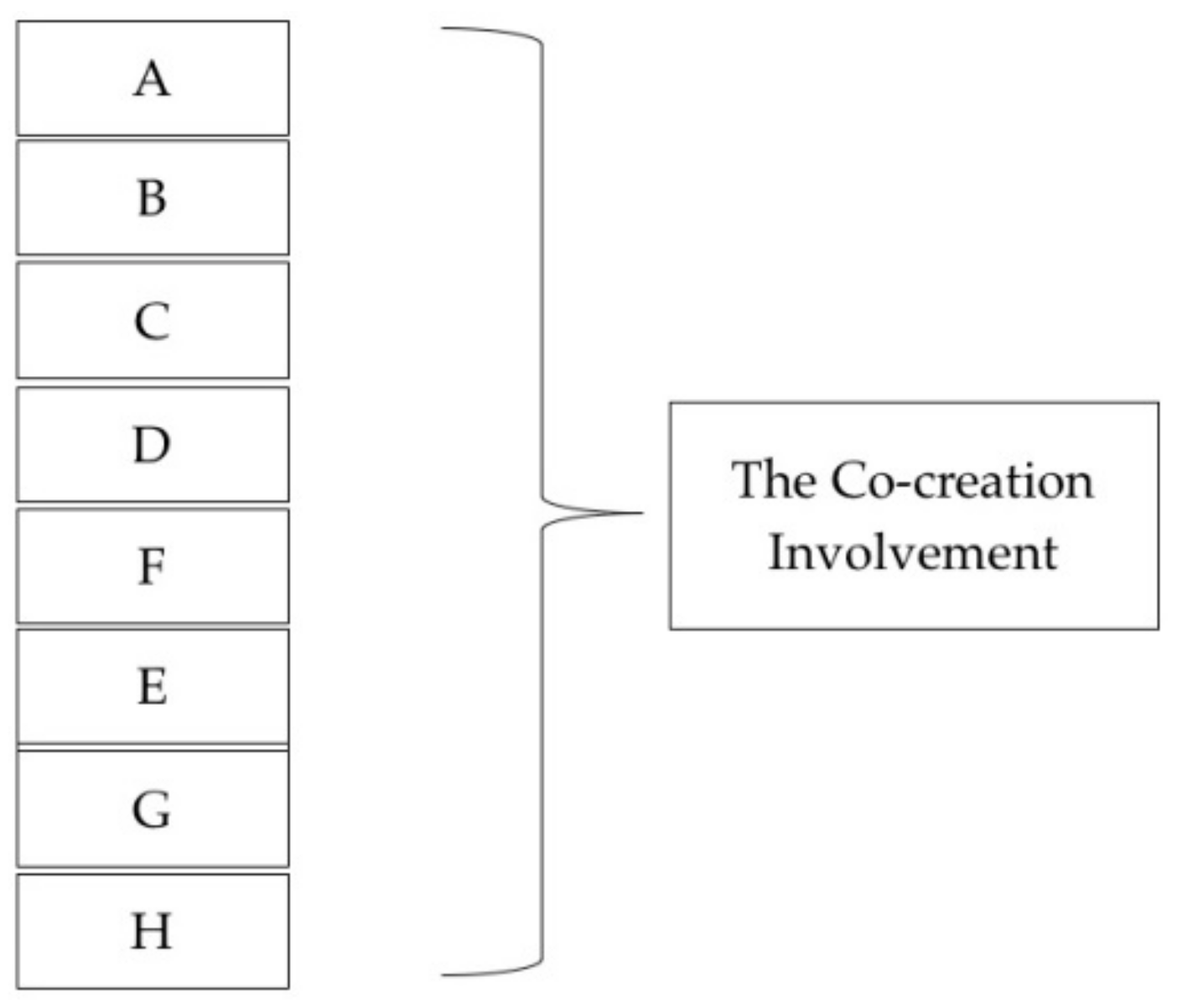

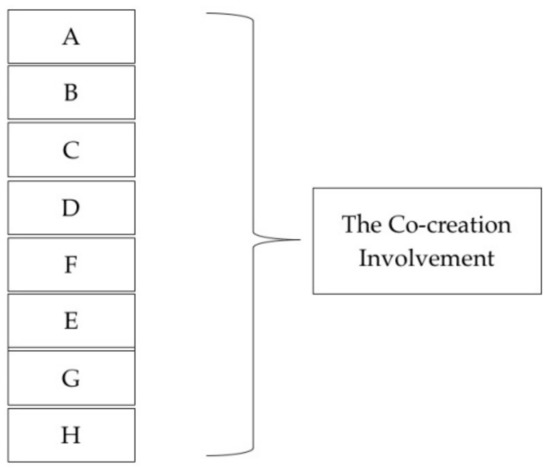

Figure 3 illustrates conceptual framework 2 (CF2).

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework 2. Source: own study. A—It is my favorite brand, so I would eagerly participate. B—The invitation to improving product usability. C—Prestige attached to cooperating with a company. D—Getting the invitation to a sample version of a new product. E—Getting a prize. F—The chance to generate ideas for brands is absolutely fantastic and challenging. G—One’s own satisfaction. H—Other.

According to CF2, the research objective is to discover the reasons that encourage participation in co-creation. Conceptual framework 3 (CF3) is demonstrated in Figure 4.

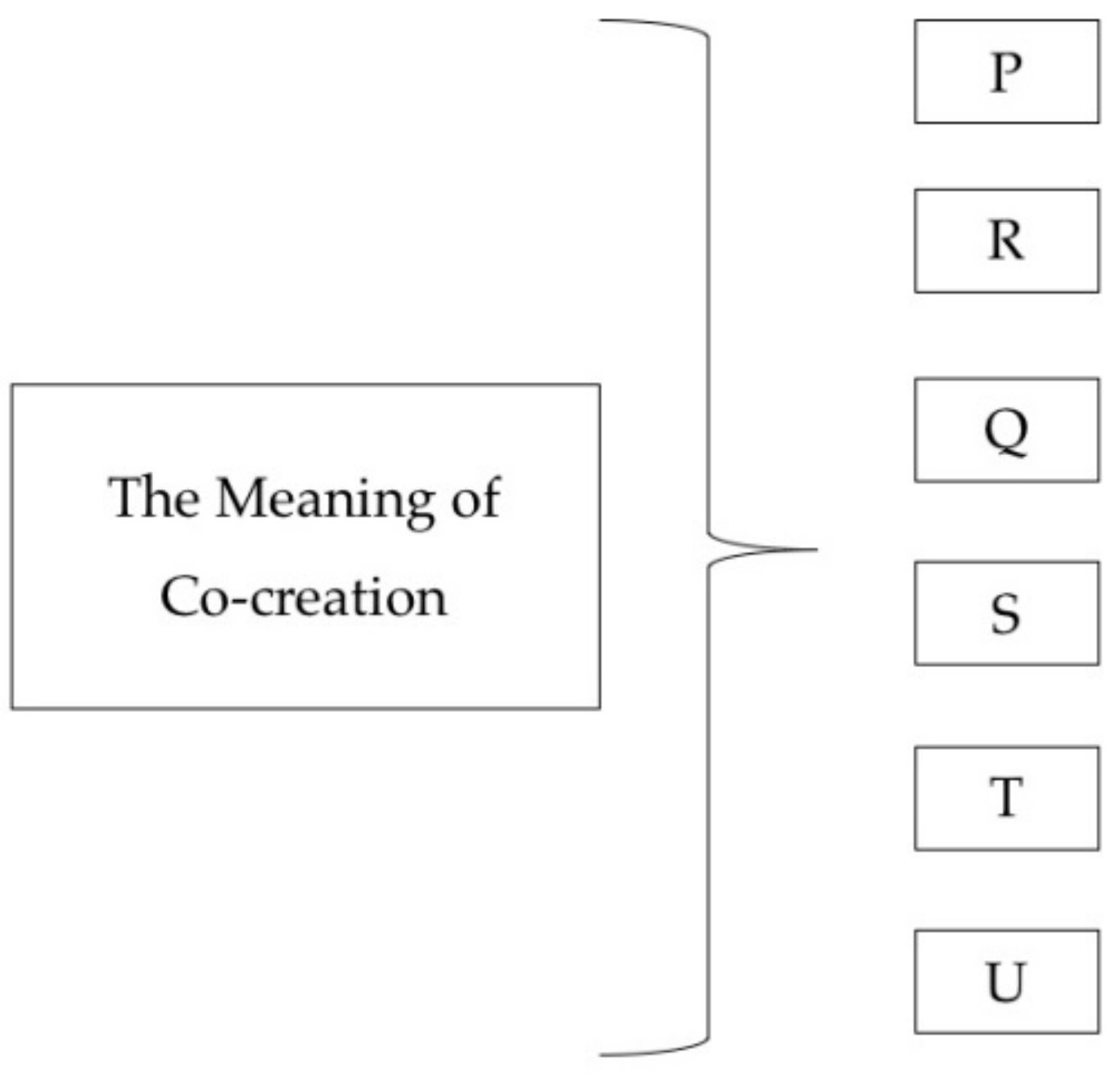

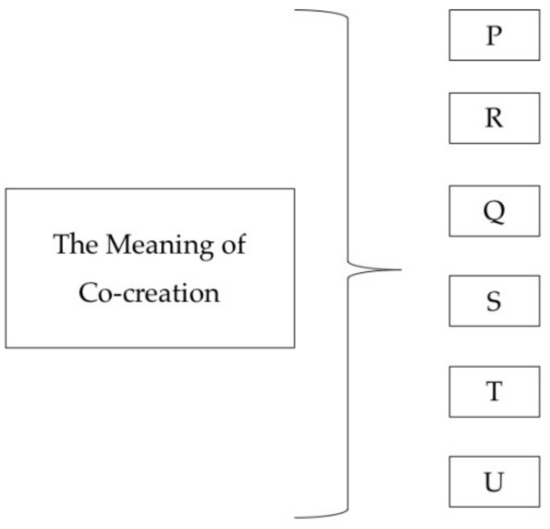

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework 3. Source: own study. P—Play. Q—Appreciation by a company. R—Sharing ideas with a company. S—Maintaining relationships with regular clients. T—One’s own satisfaction. U—Other.

According to CF3, the research objective is to determine the meaning of co-creation.

When considering the sample size and the sampling technique, each country was represented by 100 university students, and a stratified, random sampling technique was applied. The research questionnaire focused mainly on categorical (qualitative) variables, which consisted of nominal and ordinal scales. The questionnaire used a five-point Likert scale to measure different variables. Central tendency measurements such as mean value and standard deviation were applied as primary measurements in addition to percentage analysis.

This pilot study will enable researchers to discover similarities and differences between the analysed countries concerning the engagement of university students in different activities. This might be a crucial element in identifying future activities taken by companies to gain the interest of young people to participate in co-creation. From this point of view, it is worth determining the profile of the average student taking part in the research. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample have been presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 1.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the research group—gender.

Table 2.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the research group—age.

Table 3.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the research group—place of residence.

Table 4.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the research group—entrepreneurial traditions.

Table 1 illustrates the gender distribution among the sample group in percentages. According to the presented data, it can be concluded that the sample was mainly female, where the greatest percentage of females occurred in China (83%) and the lowest in Sri Lanka (55%).

Table 2 illustrates the mean age values and the related standard deviation of the sample distribution.

Definitely the lowest degree of differentiation in respondent replies could be observed when comparing age, where the average age of the study participant was 22 years old in China, Georgia, and Romania and 23 in Poland and Sri Lanka. The next table, Table 3, illustrates the place of residence in percentages.

An analysis of Table 3 concludes that the group of respondents is more varied if one takes into account their place of residence. The countries where the majority of respondents resided in urban areas included Georgia (89%), Poland (76%), China (64%), and Sri Lanka (60%). In turn, city residents constituted a minority among the respondents in Romania (38%).

The distribution of respondents coming from families of entrepreneurial traditions is equally interesting and is presented in Table 4.

The authors refer to entrepreneurial traditions as the family background in which the closest relatives were or have been entrepreneurs. Among the examined countries, only respondents from Georgia (66%) largely came from families with entrepreneurial traditions. In China and in Poland, less than one-half of those surveyed were individuals coming from a background where their own enterprises are or were run. Having one’s own company was least characteristic of the residents of Romania (28%) and Sri Lanka (36%). From the standpoint of the conducted research, the fact that respondents came from families with entrepreneurial traditions may have positively influenced their attitude towards co-creation and the knowledge of the practical operation of an enterprise.

3. Results

Taking into account the added value of the conducted research, which considers the possibility of learning the differences and similarities in respondent attitudes towards the process of co-creation, it seems important that their previous experience in this regard be verified, which is demonstrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Participation experiences in the co-creation process—cross-country analysis (in percent).

The pilot study analysis showed that there were no significant participation experiences in co-creation in the sample. According to Table 5, the highest percentage was recorded in Georgia (about 35%). Poland recorded the lowest percentage (about 6%).

Because the share of respondents that participated in co-creation was small, it is worth emphasising the reasons that would encourage them to be involved in the process of co-creation. Those reasons are demonstrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

The reasons that encourage participation in co-creation.

The researchers compiled the highest scores for different variables according to the data presented in Table 6 and Table 7 and compared these figures across the participating countries.

Table 7.

The meaning of co-creation according to university students.

According to the data presented in Table 6, China recorded the highest mean value for the variable of “it is my favourite brand, so I would eagerly participate”, and the mean value was approximately 3.70.

While in Georgia, the highest mean values were, consecutively, 3.44 and 3.48. Those values belonged to the following tested variables: “getting the invitation to a sample version of a new product” and “the chance to generate ideas for brands is absolutely fantastic and challenging”.

Poland recorded the highest mean value for the variables “getting a prize” and “getting the invitation to sample a version of a new product”. The calculated mean values that are related to the above variables were, consecutively, 3.33 and 3.35.

In Romania, the highest mean values were recorded as 3.40 and 3.58, and those mean values belonged to “the chance to generate ideas for brands is absolutely fantastic and challenging” and “one’s own satisfaction”.

Sri Lanka recorded the highest mean value for the variable “the chance to generate ideas for brands is absolutely fantastic and challenging”, and the calculated mean value was approximately 3.32.

In order to learn about the attitude of university students towards co-creation, respondents were asked to share their opinion by selecting what co-creation meant to them. The mean value and standard deviation of given answers are presented in Table 7.

According to Table 7, China recorded the highest mean value for the variables “appreciation by a company” and “sharing ideas with a company”, and the mean value was approximately 3.45 for both variables.

In Georgia, the highest mean values were, consecutively, 3.69 and 3.72. Those values belonged to the following tested variables: “maintaining relationships with regular clients” and “sharing ideas with a company”.

Poland recorded the highest mean value for the variables “sharing ideas with a company” and “appreciation by a company”. The calculated mean values related to the above variables were 3.34 and 3.52. Whereas in Romania, the highest mean values for the same variables were recorded as 3.46 and 3.53.

Sri Lanka recorded the highest mean value for the variables “sharing ideas with a company” and “maintaining relationships with regular clients”. The calculated mean values related to the above variables were, consecutively, 3.40 and 3.41.

According to the analysis, it is clear that respondents from all the countries mentioned the variable “sharing ideas with a company” as the most common factor contributing to the meaning of co-creation.

An interesting aspect of the research is the characteristics of individuals who participated in co-creation. In Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10, the authors analyzed basic data describing respondents who already had some experience in co-creation, despite their country of origin. Table 8 presents the data for gender distribution.

Table 8.

Co-creation involvement based on gender—all countries (in percent).

Table 9.

Co-creation involvement based on the place of residence—all countries (in percent).

Table 10.

Co-creation involvement based on family business traditions—all countries (in percent).

Although women were the main participants in the research, it is fair to conclude that gender does not play a significant role in co-creation involvement. Data concerning the next characteristic, place of residence, are presented in Table 9.

On the basis of data presented in Table 9, it is worth emphasising that the university students living in urban areas were more inclined to participate in the co-creation process than university students living in rural areas. Involvement in co-creation based on entrepreneurial traditions is demonstrated in Table 10.

The basic conclusion is that the “family business traditions” factor does not significantly affect co-creation involvement.

4. Discussion

The fundamental observation that can be drawn from the conducted pilot research is the fact that participation in the co-creation process is still not widely popular. While conducting this research, the authors observed, on numerous occasions, that respondents had trouble understanding the studied concept. From this point of view, further education in the comprehension of the studied concept is important along with the promotion of co-creation as an innovative tool for a company’s development. This is definitely an area in which practice needs to be combined with theory, and it ought to involve not only companies but also universities or institutions dealing with knowledge sharing. Since success of the co-creation process depends on the participation of all stakeholders, the authors propose that the principle of quadruple helix be applied in building awareness in society regarding the co-creation process. The principle of quadruple helix assumes the cooperation of not only businesses and academic circles but also of public administration and nongovernmental organizations [43].

Despite the overall limited respondents’ experience in the analysed subject, it is worth emphasising that, for instance, 35% of the individuals surveyed in Georgia took part in co-creation. In the authors’ opinion, it would be worth conducting qualitative research there, the results of which would be used for the purpose of knowledge sharing and which would constitute descriptions of good examples. Furthermore, it is worth emphasising that Georgia was, at the same time, the country whose respondents most frequently came from family backgrounds of entrepreneurial traditions (in comparison to the respondents from other countries), which could have positively translated into an openness and readiness to cooperate with business and the possessed practical knowledge.

Previous studies also stress that knowledge and experience are factors positively influencing the willingness to participate in the process of co-creation [35]. In turn, lack of suitable knowledge and opportunities, particularly in combination with product complexity, constitutes a barrier and discourages co-creation [44]. The results of the research also indicate that less complex products were more often co-created by respondents (food and drink in Poland, Sri Lanka, and Romania; books in China and Georgia; services in Georgia and Sri Lanka; and shoes in Georgia and Poland) [45]. This fact may result not only from respondents’ insufficient knowledge or experience but also from their young age, type of products purchased, or lack of sufficient financial means to purchase luxurious goods, which frequently features a greater degree of complexity.

Considering the respondents’ limited experience in co-creation so far, the fact that they did not have a negative attitude towards this process needs to be taken into account. Respondents’ replies indicate their willingness, openness, and positive attitude towards co-creation.

Literature on the subject frequently lists the benefits arising from the application of co-creation [46]; however, knowledge is not yet sufficiently propagated. Therefore, the authors see potential for further research and for publications to sort the knowledge on not only the advantages of co-creation but also the barriers or difficulties that hamper the development of the studied phenomenon.

Taking into account the objective of this article, which was to find the differences and similarities among the respondents from various countries considering their proclivity towards the process of co-creation, it must be stressed that the results chiefly point out existing similarities and only slight differences in the attitude towards co-creation. The occurrence of small differences despite great distances may result from two example reasons. First of all, the levelling of differences may be owed to globalization and the resultant similarity in young people’s behaviour [45]. Secondly, it is possible that cultural differences do not play a significant role in the attitude towards co-creation. Further research would need to verify whether the willingness to participate in co-creation is not affected by culture. In these circumstances, it would also be worth analysing other variables such as age, education, attitude towards novelties, or gender.

The greatest difference regarding the attitude towards co-creation depending on the country of origin concerned respondents’ expectations for a possible reward (as shown in Table 6). In four out of the five studied countries, respondents most frequently emphasised that they found the very idea of an incentive enough to participate in the process. Poland is the exception among them, since the individuals surveyed in this country would expect a concrete reward. It was only in this country that the results of previous studies on co-creation were confirmed, according to which obtaining particular economic benefits is one the main factors influencing the involvement into the process of co-creation [47]. For the customer, co-creation often equals investments in terms of not only skills and time but also psychological efforts and money [48]. The customer compares these investments with benefits, which (in this case) are represented by their satisfaction. Increased involvement generates high expectations. The problem arises when those expectations are not met, which leads to consumer disappointment [49]. Discrepancies in the results are reflected in the literature on the subject, where consent is lacking as to how the process of co-creation ought to be implemented (including how to motivate participation in the process) [50,51,52]. In turn, the studies conducted so far confirm that a positive attitude toward co-creation encourages participation in the process [11,32].

5. Conclusions

In perceiving the changes in a company’s environment as well as the increasingly stronger role of the customer, the aim of this paper was to examine the differences and similarities among respondents from different countries (China, Georgia, Poland, Romania, Sri Lanka) considering their attitude towards the process of co-creation. This pilot study has proven helpful in getting a preliminary understanding about the research phenomena. As a result of this study, the researchers came to a few conclusions. The first conclusion that can be drawn from this research is the fact that basic variables, such as gender, demographic factors, or entrepreneurial traditions, had very little impact on respondents’ engagement in co-creation. In addition to that, the process of co-creation had similar meanings for young people who participated in the study. Despite different countries of origin, they agreed that co-creation means primarily sharing ideas with a company. Moreover, the study found that the most common reasons that motivated university students to get engaged with the co-creation process were the emergence of an opportunity or an invitation to participate in the co-creation process.

The literature stresses the importance of customer involvement in the process of co-creation, and it describes pilot research that shows university students are eager to engage in this activity and have positive attitudes towards it. Co-creation is an opportunity for a company to boost innovativeness, create products in accordance with customer expectations, build trust and loyalty, and act in a more sustainable way. There is synergy between the process of co-creation and sustainable functioning of an enterprise since an organisation cannot properly use co-creation without being sustainable.

The researchers would also like to briefly highlight the significant limitations of the study. As mentioned earlier, this was a pilot study, and the sample size and analysed countries were not sufficient to generalize the findings. Despite these limitations, the entire analysis was based on descriptive measurements such as the mean value and standard deviation. The authors share the opinion that this research study can be identified as a good starting point for further research studies that will focus on examining the phenomena of co-creation.

The main contribution presented in this paper is to promote co-creation as an innovative way to develop companies situated in different parts of the world. The results bring additional knowledge on factors that would encourage university students to participate in co-creation. It can be concluded that, despite the place of operation, companies could motivate customers to participate in an analysed process in a similar way.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.-K., M.W.-F.; methodology, S.M.-K., M.W.-F., and K.S.D.F.; validation, S.M.-K., M.W.-F.; formal analysis, K.S.D.F.; investigation, S.M.-K., M.W.-F.; data curation, K.S.D.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.-K., M.W.-F., and K.S.D.F.; writing—review and editing, S.M.-K.; visualization, K.S.D.F.; project administration, S.M.-K., M.W.-F.

Funding

The project is financed within the framework of the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the name "Regional Excellence Initiative" in the years 2019–2022; project number 001/RID/2018/19; the amount of financing PLN 10,684,000.00.

Acknowledgments

We wish to extend our kind thanks to all our foreign partners and to the young people who were willing to participate in the study. Their contributions are highly appreciated and gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rill, B.R.; Hämäläinen, M.M. The Art of Co-Creation, A Guidebook for Practitioners; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Ozcan, K. The Co-Creation Paradigm; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-8047-9075-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mele, C. Conflicts and value co-creation in project networks. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, G. Marketing Współtworzenia Wartości Z Klientem Jako Instrument Tworzenia Innowacji. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wroclawiu 2016, 458, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and Axioms: An Extension and Update of Service-Dominant Logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, J.B.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy. Work is Theatre and Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, V. It’s about human experience ... and beyond, to co-creation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perello-Marín, M.R.; Ribes-Giner, G.; Pantoja Díaz, O. Enhancing Education for Sustainable Development in Environmental University Programmes: A Co-Creation Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hern, M.S.; Rindfleisch, A. Customer co-creation: A typology and research agenda. Rev. Mark. Res. 2017, 6, 108–130. [Google Scholar]

- Piller, F.; Ihl, C.; Vossen, A. A typology of customer co-creation in the innovation Process. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.Y.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Troye, S.V. Trying to prosume: Toward a theory of consumers as co-creators of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissemann, U.S.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Vargo, S.L.; Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Van Kasteren, Y. Health care customer value co-creation practice styles. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 370–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Przyszłość Konkurencji; PWE: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, B.; Kohli, A. Co-creating the Voice of the Customer—The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel, E. A customer-active paradigm for industrial product idea generation. Res. Policy 1978, 7, 240–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, E. Democratizing Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Füller, J.; Matzler, K.; Hoppe, M. Brand community members as a source of innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etgar, M. A descriptive model of the consumer co-production process. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Yim, C.K.; Lam, S.S.K. Is customer participation in value creation a double-edged sword? Evidence from professional financial services across cultures. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, J.; Tellis, G.J.; Griffin, A. Research on Innovation: A Review and Agenda for Marketing Science. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 551–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, F.T.; Ihl, C. Open Innovation with Customers—Foundations, Competences and International Trends, Expert Study commissioned by the European Union, The German Federal Ministry of Research, and Europäischer Sozialfond ESF; International Monitoring: Aachen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Revilla-Camacho, M.A.; Cossío-Silva, F.J.; Vega-Vázquez, M. Seeking a Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Periods of Economic Recession for SMEs and Entrepreneurs: The Role of Value Co-creation and Customer Trust in the Service Provider. In Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Economic Crisis: 69 Lessons for Research, Policy and Practice; Rüdiger, K., Peris-Ortiz, M., Blanco-González, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Lung, L.; Lee-Yun, P.; Chin-Hsien, H.; De-Chih, L. Exploring the Sustainability Correlation of Value Co-Creation and Customer Loyalty-A Case Study of Fitness Clubs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Nejati, M.; Shafaei, A. The influence of sustainability on students’ perceived image and trust towards university. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2015, 9, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyukorong, R.A. Model for Building and Implem enting Customer Value Co-creation Agendas. J. Mark. Consum. Res. 2016, 213, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Witell, L.; Kristensson, P.; Gustafsson, A.; Löfgren, M. Idea generation: Customer co-creation versus traditional markeit research techniques. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendapudi, N.; Leone, R.P. Psychological implications of customer participation in co-production. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, P.; Wijenayake, S.I.; Wiścicka, M. Women in Co-Creation: Comparative Study between Poland and Sri Lanka. In Development of Women and Management; Misiak-Kwit, S., Wiścicka, M., Eds.; Winnet Centre of Excellence Series: Kelaniya, Sri Lanka, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wiscicka-Fernando, M. Sustainability Marketing Tools in Small and Medium Enterprises. In The Sustainable Marketing Concept in European Smes: Insights from The Food & Drink Industry; Rudawska, E., Ed.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 81–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lusch, R.F.; Brown, S.W.; Brunswick, G.J. A general framework for explaining internal vs. external exchange. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1992, 20, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, C.; Pucci, T.; Silvestri, C.; Aquilani, B. Does Value Co-Creation Really Matter? An Investigation of Italian Millennials Intention to Buy Electric Cars. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A.; Brown, S.W.; Sirianni, N.J. The secret to true service innovation. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control, 10th ed.; Prentice-Hill: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, J.; Ardley, B. The relationship between Innovation and the Co-creation Process. JMS 2019, 63, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Gouillart, F. Building the co-creative enterprise. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E. The Social Psychology of Leisure and Recreation; WC Brown Co. Publishers: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak-Kwit, S.; Hozer-Koćmiel, M. Współpraca biznesowa kobiet na przykładzie modelu WCR i metody BST, Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach 2016, 254, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barrutia, J.M.; Paredes, M.R.; Echebarria, C. Value co-creation in e-commerce contexts: Does product type matter? Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak-Kwit, S.; Wiścicka, M. Building Relations between a Company and Consumers through Co-creation: Polish and Chinese Context. Kelaniya J. Manag. 2017, 6, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Partanen, J. Co-creating Value from Knowledge-Intensive Business Services in Manufacturing Firms: The Moderating Role of Relationship Learning in Supplier–Customer Interactions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2498–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-Dominant Logic: Premises, Perspectives, Possibilities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Chandy, R.; Dorotic, M.; Krafft, M.; Singh, S.S. Consumer cocreation in new product development. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, S.; Wittkowski, K.; Handrich, M.; Falk, T. The dark side of customer co-creation: Exploring the consequences of failed co-created services. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensson, P.; Matthing, J.; Johansson, N. Key strategies for the successful involvement of customers in the co-creation of new technology-based services. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2008, 19, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, A.; Kristensson, P.; Witell, L. Customer co-creation in service innovation: A matter of communication? J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).