Sustainable Workplace: The Moderating Role of Office Design on the Relationship between Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour in Uzbekistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

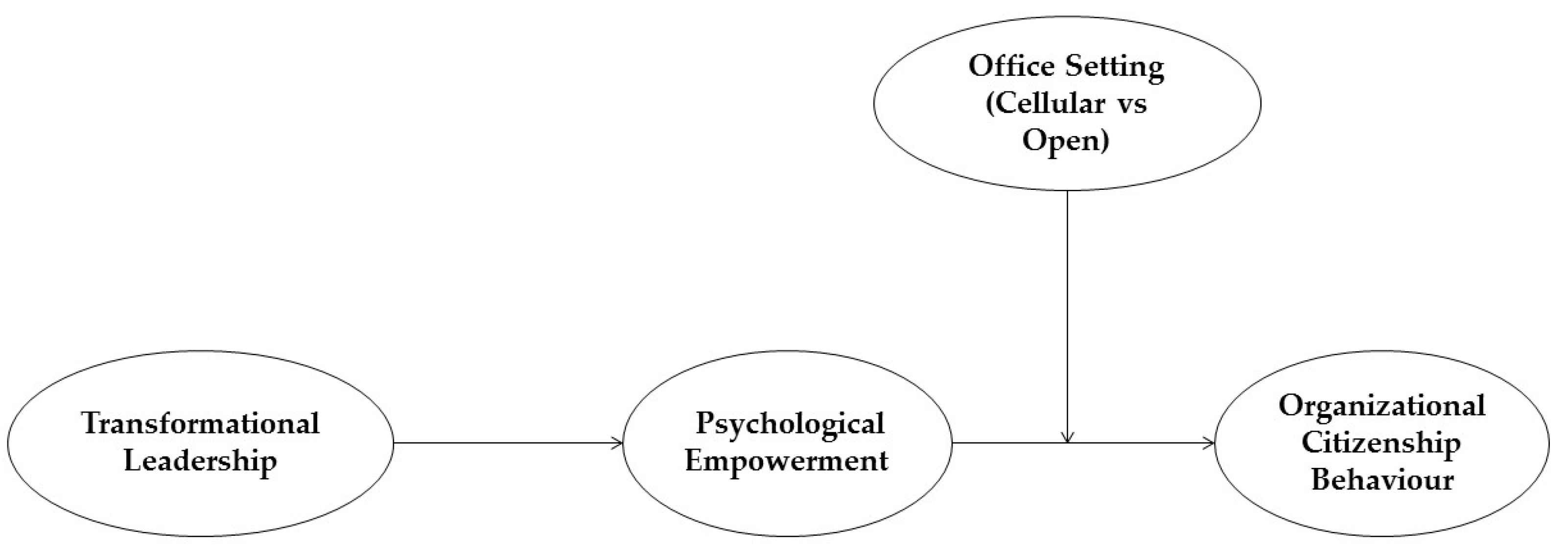

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Transformational Leadership and Psychological Empowerment

2.2. Psychological Empowerment and OCB

2.3. The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and OCB

2.4. The Moderating Role of Office Design (Cellular vs. Open-Plan) in the Relationship between Psychological Empowerment and OCB

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Transformational Leadership

3.2.2. Psychological Empowerment

3.2.3. Organizational Citizenship Behaviour

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Transformational Leadership [120].

- My supervisor communicates a clear and positive vision of the future.

- My supervisor treats staff as individuals, supports and encourages their development.

- My supervisor gives encouragement and recognition to staff.

- My supervisor fosters trust, involvement and cooperation among team members.

- My supervisor encourages thinking about problems in new ways and questions assumptions.

- My supervisor is clear about his/her values and practices what he/she preaches.

- My supervisor instils pride and respect in others and inspires me by being highly competent.

- Psychological Empowerment [56].

- I am confident about my ability to do my job.

- I am self-assured about my capabilities to perform my work activities.

- I have mastered the skills necessary for my job.

- I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job.

- I can decide on my own how to go about doing my work.

- I have considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do my job.

- My impact on what happens in my department is large.

- I have a great deal of control over what happens in my department.

- I have significant influence over what happens in my department.

- The work I do is very important to me.

- My job activities are personally meaningful to me.

- The work I do is meaningful to me.

- Organizational Citizenship Behaviour [44].

- This employee attends functions that are not required but that help the organizational image.

- This employee offers ideas to improve the functioning of the organization.

- This employee takes action to protect the organization from potential problems.

References

- Duradoni, M.D.F.; Di Fabio, A. Intrapreneurial self-capital and sustainable innovative behavior within organizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A.P.; Peiró, J. Human Capital Sustainability Leadership to promote sustainable development and healthy organizations: A new scale. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A.R.; Rosen, M.A. Opening the black box of psychological processes in the science of sustainable development: A new frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A.K.; Kenny, M. Academic relational civility as a key resource for sustaining well-being. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, F.D.G.; Gield, B.; Gaylin, K.; Sayer, S. Office design in a community college: Effect on work and communication patterns. Environ. Behav. 1983, 15, 699–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, D. Office Landscape—A Systems Concept. In Management Conference, Improving Office Environment; Business Press: Elmhurst, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A.E.; Lewis, M.S. Planning the Office Landscape; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, S. Open-Plan Offices: New Ideas, Experience and Improvements; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson, C.B.; Bodin, L. Office type in relation to health, well-being, and job satisfaction among employees. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 636–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vischer, J.C. Towards an environmental psychology of workspace: How people are affected by environments for work. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2008, 51, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbring, T.; Pareigis, J.; Wästlund, E.; Makrygiannis, A.; Lindström, A. The relationship between office type and job satisfaction: Testing a multiple mediation model through ease of interaction and well-being. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2018, 44, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, P.J.; Jeon, J.Y. A laboratory study for assessing speech privacy in a simulated open-plan office. Indoor Air 2014, 24, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Lee, B.K.; Jeon, J.Y.; Zhang, M.; Kang, J. Impact of noise on self-rated job satisfaction and health in open-plan offices: A structural equation modelling approach. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; De Dear, R. Workspace satisfaction: The privacy-communication trade-off in open-plan offices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seddigh, A.; Berntson, E.; Jönsson, F.; Danielson, C.B.; Westerlund, H. The effect of noise absorption variation in open-plan offices: A field study with a cross-over design. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leder, S.; Newsham, G.R.; Veitch, J.A.; Mancini, S.; Charles, K.E. Effects of office environment on employee satisfaction: A new analysis. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierrette, M.; Parizet, E.; Chevret, P.; Chatillon, J. Noise effect on comfort in open-space offices: Development of an assessment questionnaire. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazanchi, S.; Sprinkle, T.A.; Masterson, S.S.; Tong, N. A spatial model of work relationships: The relationship-building and relationship-straining effects of workspace design. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullahorn, J.T. Distance and friendship as factors in the gross interaction matrix. Sociometry 1952, 15, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books/DC Heath and Com: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Law, K.S.; Zhang, M.J.; Li, Y.N.; Liang, Y. It’s mine! Psychological ownership of one’s job explains positive and negative workplace outcomes of job engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yang, S.; Qiu, T.; Gao, X.; Wu, H. Moderating role of self-esteem between perceived organizational support and subjective well-being in Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicolini, G.; Comparcini, D.; Simonetti, V. Workplace empowerment and nurses’ job satisfaction: A systematic literature review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maggio, I.; Santilli, S.; Nota, L.; Ginevra, M.C. The predictive role of self-determination and psychological empowerment on job satisfaction in persons with intellectual disability. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2019, 3, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Winston, B.E.; Tatone, G.R.; Crowson, H.M. Exploring a model of servant leadership, empowerment, and commitment in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Manag. 2018, 29, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Dhaliwal, R.S.; Nobi, K. Impact of structural empowerment on organizational commitment: The mediating role of women’s psychological empowerment. Vision 2018, 22, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.C.; Kumar, S.; Gahlawat, N. Empowering leadership and job performance: Mediating role of psychological empowerment. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Innocenzo, L.; Luciano, M.M.; Mathieu, J.E.; Maynard, M.T.; Chen, G. Empowered to perform: A multilevel investigation of the influence of empowerment on performance in hospital units. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1290–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, B.K.; Jo, S.J. The effects of perceived authentic leadership and core self-evaluations on organizational citizenship behavior: The role of psychological empowerment as a partial mediator. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, J.; Stander, M.W.; Van Zyl, L.E. Leadership empowering behaviour, psychological empowerment, organisational citizenship behaviours and turnover intention in a manufacturing division. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2015, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Cooper, B.; Sendjaya, S. How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vischer, J.C. The effects of the physical environment on job performance: Towards a theoretical model of workspace stress. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2007, 23, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdenitsch, C.K. Christian Hertel, Guido Need–supply fit in an activity-based flexible office: A longitudinal study during relocation. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, A.; WKozusznik, M.; Peiró, J.M.; Mateo, C. The Role of Employees’ Work Patterns and Office Type Fit (and Misfit) in the Relationships Between Employee Well-Being and Performance. Environ. Behav. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrab, M.; Zumrah, A.R.; Almaamari, Q.; Al-Tahitah, A.N.; Isaac, O.; Ameen, A. The role of psychological empowerment as a mediating variable between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behaviour in Malaysian higher education institutions. Int. J. Manag. Hum. Sci. 2018, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wernsing, T. From transactional and transformational leadership to authentic leadership. Oxf. Handb. Leadersh. 2012, 6, 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis, J.; Bastardoz, N.; Liu, Y.; Schriesheim, C.A. What makes articles highly cited? Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 152–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinh, J.E.; Lord, R.G.; Gardner, W.L.; Meuser, J.D.; Liden, R.C.; Hu, J. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: Current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diaz-Saenz, H.R. Transformational leadership. Sage Handb. Leadersh. 2011, 5, 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Thurgood, G.R.; Smith, T.A.; Courtright, S.H. Collective organizational engagement: Linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, X.; Ni, J. The impact of transformational leadership on employee sustainable performance: The mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butar, I.D.B.; Sendjaya, S.; Pekerti, A.A. Transformational Leadership and Follower Citizenship Behavior: The Roles of Paternalism and Institutional Collectivism. In Leading for High Performance in Asia; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; Matute, J. Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puni, A.M. Ibrahim Asamoah, Emmanuel Transformational leadership and job satisfaction: The moderating effect of contingent reward. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Petty, R.J.; Bodner, T.E.; Perrigino, M.B.; Hammer, L.B.; Yragui, N.L.; Michel, J.S. Lasting impression: Transformational leadership and family supportive supervision as resources for well-being and performance. Occup. Health Sci. 2018, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, E.K.A. Transformational Leadership An Analysis of Effects on Employee Well-Being. J. Integr. Stud. 2019, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, S.Y. How to enhance sustainability through transformational leadership: The important role of employees’ forgiveness. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pradhan, S.; Jena, L.K. Does Meaningful Work Explains the Relationship Between Transformational Leadership and Innovative Work Behaviour? Vikalpa 2019, 44, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jha, S. Transformational leadership and psychological empowerment: Determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. South Asian J. Glob. Bus. Res. 2014, 3, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.T.; Gilson, L.L.; Mathieu, J.E. Empowerment—Fad or fab? A multilevel review of the past two decades of research. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1231–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Power and Echange in Social Life. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwjFw5eEyqfmAhVXfd4KHV56BIMQFjAAegQIAxAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.garfield.library.upenn.edu%2Fclassics1989%2FA1989CA26300001.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0zjJ2L0KC8S4GzzyJRq0Lv (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Leadership, T. Industry, Military and Educational Impact; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Afsar, B.; FBadir, Y.; Bin Saeed, B. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 1270–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.K.; Panda, M.; Jena, L.K. Transformational leadership and psychological empowerment: The mediating effect of organizational culture in Indian retail industry. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, T.; Eden, D.; Avolio, B.J.; Shamir, B. Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 735–744. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir, B.; House, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N. Charismatic Leadership in Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kovjanic, S.; Schuh, S.C.; Jonas, K. Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. Green Transformational leadership and green performance: The mediation effects of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6604–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A. Understanding transformational leadership–employee performance links: The role of relational identification and self-efficacy. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.A.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; McKee, M.C. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin Ghadi, M.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. Transformational leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of meaning in work. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Gardner, D.G.; Cummings, L.L.; Dunham, R.B. Organization-based self-esteem: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 622–648. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, D.G.; Pierce, J.L. Self-esteem and self-efficacy within the organizational context: An empirical examination. Group Organ. Manag. 1998, 23, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alzayed, M.; Jauhar, J.; Mohaidin, Z. The mediating effect of affective organizational commitment in the relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: A conceptual model. Asian Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kernodle, T.A.; Noble, D. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its importance in academics. Am. J. Bus. Educ. 2013, 6, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, G.; Kaur, K. An empirical assessment of impact of organizational climate on organizational citizenship behaviour. Paradigm 2015, 19, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Welsh, D.T.; Mai, K.M. Surveying for “artifacts”: The susceptibility of the OCB–performance evaluation relationship to common rater, item, and measurement context effects. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.I.; Akhtar, S.A.; Zaheer, A. Impact of transformational and servant leadership on organizational performance: A comparative analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Van Dyne, L.; Kamdar, D.; Johnson, R.E. Why and when do motives matter? An integrative model of motives, role cognitions, and social support as predictors of OCB. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 121, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Kizilos, M.A.; Nason, S.W. A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness satisfaction, and strain. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 679–704. [Google Scholar]

- Peccei, R.; Rosenthal, P. Delivering customer-oriented behaviour through empowerment: An empirical test of HRM assumptions. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 831–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, J.; Yaacob, H.F.; Rahman, S.A.A. The Effects of Psychological Empowerment on Organisational Citizenship Behaviour among Malaysian Nurses. Manag. Res. Spectr. 2019, 9, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Noranee, S.; Abdullah, N.; Mohd, R.; Khamis, M.R.; Aziz, R.A.; Som, R.M.; Ammirul, E.A.M. The Influence of Employee Empowerment on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. In Proceedings of the 2nd Advances in Business Research International Conference, Langkawi, Malaysia, 16–17 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Byaruhanga, I.; Othuma, B.P. Enhancing organizational citizenship behavior: The role of employee empowerment, trust and engagement. In Entrepreneurship and SME Management Across Africa; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Rich, G.A. Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S.T.; Schaubroeck, J.M.; Peng, A.C. Transforming followers’ value internalization and role self-efficacy: Dual processes promoting performance and peer norm-enforcement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.K.; Davis, R.S.; Pandey, S.; Peng, S. Transformational leadership and the use of normative public values: Can employees be inspired to serve larger public purposes? Public Adm. 2016, 94, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, A.N.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.; Stam, D. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirak, R.; Peng, A.C.; Carmeli, A.; Schaubroeck, J.M. Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simola, S.; Barling, J.; Turner, N. Transformational leadership and leaders’ mode of care reasoning. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegall, M.; Gardner, S. Contextual factors of psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2000, 29, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; de Pablos Heredero, C.; Ahmed, M. A three-wave time-lagged study of mediation between positive feedback and organizational citizenship behavior: The role of organization-based self-esteem. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wat, D.; Shaffer, M.A. Equity and relationship quality influences on organizational citizenship behaviors: The mediating role of trust in the supervisor and empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2005, 34, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 1, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, M.; Dupre, K.; Arnold, K.A. Processes through which transformational leaders affect employee psychological health. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dust, S.B.; Resick, C.J.; Mawritz, M.B. Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic–organic contexts. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, A. The open-plan office: A systematic investigation of employee reactions to their work environment. Environ. Behav. 1982, 14, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, A.; Chugh, J.S.; Kline, T. Traditional versus open office design: A longitudinal field study. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geen, R.G.; Gange, J.J. Drive theory of social facilitation: Twelve years of theory and research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, C.G.; Li, Z.F.; Shi, Y. Corporate social responsibility and CEO risk-taking incentives. SSRN 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Minor, D.B.; Wang, J.; Yu, C. A learning curve of the market: Chasing alpha of socially responsible firms. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2019, 109, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Konovsky, M. Cognitive versus affective determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A.; Sharoni, G. Organizational citizenship behavior, organizational justice, job stress, and workfamily conflict: Examination of their interrelationships with respondents from a non-Western culture. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2014, 30, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farid, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ma, J.; Castro-González, S.; Khattak, A.; Khan, M.K. Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects of organizational justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allen, T.J.; Gerstberger, P.G. A field experiment to improve communications in a product engineering department: The nonterritorial office. Hum. Factors 1973, 15, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahn, G.L. Face-to-face communication in an office setting: The effects of position, proximity, and exposure. Commun. Res. 1991, 18, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, E.; Burt, R.E.; Kamp, D. Privacy at work: Architectural correlates of job satisfaction and job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, M.J.; Kaplan, A. The office environment: Space planning and affective behavior. Hum. Factors 1972, 14, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D. Why do lay people believe that satisfaction and performance are correlated? Possible sources of a commonsense theory. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2003, 24, 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandlousi, N.S.A.E.; Ali, A.J.; Abdollahi, A. Organizational citizenship behavior in concern of communication satisfaction: The role of the formal and informal communication. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolino, M.C. Citizenship and impression management: Good soldiers or good actors? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Pugh, S.D. Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 656–669. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, W.M. Organizational Goals Versus the Dominant Coalition: A Critical View of the Value of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2006, 7, 258–273. [Google Scholar]

- Banbury, S.P.; Berry, D.C. Office noise and employee concentration: Identifying causes of disruption and potential improvements. Ergonomics 2005, 48, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Croon, E.; Sluiter, J.; Kuijer, P.P.; Frings-Dresen, M. The effect of office concepts on worker health and performance: A systematic review of the literature. Ergonomics 2005, 48, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Blasio, S.; Strepi, L.; Puglisi, G.E.; Astolfi, A. A Cross-Sectional Survey on the Impact of Irrelevant Speech Noise on Annoyance, Mental Health and Well-being, Performance and Occupants’ Behavior in Shared and Open-Plan Offices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Open-Plan Offices are Not Inherently Bad—You are Probably Using Them Wrong. 2019. Available online: http://theconversation.com/open-plan-offices-are-not-inherently-bad-youre-probably-just-using-them-wrong-113689 (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 5, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Carless, S.A.; Wearing, A.J.; Mann, L. A short measure of transformational leadership. J. Bus. Psychol. 2000, 14, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Egan, T.; O’Reilly, C., III. Being different: Relational demography and organizational attachment. Acad. Manag. Proc. 1991, 1, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Cunha, M.P.E. Organisational citizenship behaviours and effectiveness: An empirical study in two small insurance companies. Serv. Ind. J. 2008, 28, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0049124192021002005 (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Chatterjee, S.H. AS Price, Analysis of collinear data. In Regression Analysis by Example; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 143–174. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sijbom, R.B.; Lang, J.W.; Anseel, F. Leaders’ achievement goals predict employee burnout above and beyond employees’ own achievement goals. J. Personal. 2019, 87, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffens, N.K.; Yang, J.; Jetten, J.; Haslam, S.A.; Lipponen, J. The unfolding impact of leader identity entrepreneurship on burnout, work engagement, and turnover intentions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Personal Characteristics | No. | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Office Design | Open-plan | 181 | 83.80 |

| Cellular | 35 | 16.20 | |

| Gender | Male | 99 | 45.83 |

| Female | 117 | 54.17 | |

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 33 | 15.29 |

| 25–31 | 70 | 32.41 | |

| 32–38 | 54 | 25 | |

| 39–45 | 41 | 18.98 | |

| 46–55 | 16 | 7.41 | |

| 56–65 | 2 | 0.92 | |

| Education level | Upper-secondary school | 1 | 0.46 |

| 3-years college | 86 | 39.81 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 91 | 42.13 | |

| Master’s degree | 38 | 17.59 | |

| Organizational tenure (years) | <1 | 39 | 18.06 |

| 1–3 | 57 | 26.4 | |

| 4–6 | 35 | 16.19 | |

| 7–10 | 51 | 23.6 | |

| 11–15 | 28 | 12.96 | |

| 16–20 | 6 | 2.77 |

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 33.30 | 8.49 | |||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.54 | 0.50 | −0.05 | ||||||

| 3. Tenure | 5.61 | 4.63 | 0.59 ** | 0.17 * | |||||

| 4. Education | 2.77 | 0.74 | 0.29 ** | −0.01 | 0.12 | ||||

| 5. Office Setting | 0.84 | 0.37 | −0.20 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.10 | 0.12 | |||

| 6. TRL | 3.76 | 0.58 | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.22 ** | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| 7. PE | 3.83 | 0.42 | −0.00 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.39 ** | |

| 8. OCB | 3.97 | 0.55 | 0.16 * | 0.17 * | 0.12 | 0.14 * | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.18 * |

| Model | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ∆df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Factor model (hypothesized model) | 272.07 *** | 198 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.04 | - | - |

| 3-Factor model (TRL and PE merged) | 489.39 *** | 201 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 3 | 217.32 *** |

| 2-Factor model (TRL, PE and office setting merged) | 785.03 *** | 203 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.12 | 5 | 512.96 *** |

| 1-Factor model (all variables merged) | 978.56 *** | 204 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 6 | 706.49 *** |

| Variables | Psychological Empowerment | Organizational Citizenship Behaviour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

| Employee age | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Employee gender | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.17 * | 0.15 * | 0.15 * |

| Organizational tenure | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| TRL | 0.41 *** | 0.06 | 0.05 | ||

| PE | 0.16 * | 0.05 | |||

| Office setting | 0.08 | 0.08 | |||

| PE x Office setting | 0.18 * | ||||

| R2 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| F | 0.11 | 7.95 *** | 3.60 ** | 3.41 ** | 3.59 *** |

| ∆ | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| ∆F | 39.22 *** | 3.01 * | 4.44 * | ||

| Indirect Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRL→PE→OCB | 0.06 | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.13] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khusanova, R.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Sustainable Workplace: The Moderating Role of Office Design on the Relationship between Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour in Uzbekistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247024

Khusanova R, Choi SB, Kang S-W. Sustainable Workplace: The Moderating Role of Office Design on the Relationship between Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour in Uzbekistan. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):7024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247024

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhusanova, Rushana, Suk Bong Choi, and Seung-Wan Kang. 2019. "Sustainable Workplace: The Moderating Role of Office Design on the Relationship between Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour in Uzbekistan" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 7024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247024