Abstract

Appreciative Inquiry was employed to understand the mutual impact of Theodore Roosevelt National Park and nearby communities’ relationships with tourism. Specifically, the goals of this study were to: understand the role of Theodore Roosevelt National Park related to stimulating regional tourism; to ascertain gateway community resident perceptions of benefits from tourism as it relates to economic development and quality of; and, to explore nearby communities’ relationships with the park and how those communities may help influence quality visitor experiences, advance park goals, and develop and leverage partnerships. Results include a collection of emergent themes from the community inquiry related to resource access and tourism management, citizen and community engagement, conservation, marketing, and communication between the park and neighboring residents. These findings illuminate the need to understand nearby communities’ relationship to public lands and regional sustainability support between public land managers and these communities.

1. Introduction

The majority of park and protected area (PPA) systems around the world have experienced dramatic increases in visitation within the last century [1,2]. In some regard, these increases provide opportunities for PPA managers. Tourism in PPAs is widely recognized as an essential tool for garnering political and economic support for conservation as well as for increasing the quality of life for nearby communities [3,4]. At the same time, poorly managed tourism development in and around PPAs can threaten the environmental integrity of the area and fail to produce the desired social and economic benefits to local communities [5,6]. This fine line between opportunity and threat emphasizes the need to implement sustainable tourism development practices in PPAs that involve direct and intentional engagement with local communities [4,7].

Public participation is a crucial component of national park planning and management in the United States. The U.S. National Park Service (NPS) is legally required to engage with the public when making management decisions by a variety of laws, policies, and director’s orders such as those contained in the National Park Service National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Handbook [8]. Regardless of legal requirements and policy, public participation is a meaningful endeavor because it can enhance mutually beneficial relationships between park and protected area (PPA) managers and local communities [9,10,11]. Likewise, in the absence of effective public participation, relationships between PPAs and communities can flounder for decades [12].

While public participation can help PPA managers and local community members achieve shared goals, engaged public participation is difficult. For example, public involvement techniques traditionally used to meet all legal requirements, such as open house meetings and the distribution of technical planning documents, have been found ineffective in promoting meaningful collaboration [13]. While PPA managers often acknowledge the need for collaboration, additional barriers including a lack of resources, high staff turnover, long-distance commuting, and a reliance on technical jargon have hindered the adoption of alternative strategies [13,14]. Even when these barriers can be overcome, determining which public engagement strategies to pursue can be challenging. For example, evidence suggests that policy and engagement strategies that work well in one community may not work well in another [15,16,17,18].

Due to the importance of and challenges associated with effective public participation relative to PPAs management, identifying and assessing the use of alternative public engagement processes with application to a diversity of communities is warranted. In 2017, Theodore Roosevelt National Park initiated a strategic planning process, which included research to understand how visitors use the park and perceptions of residents within three gateway communities surrounding the park. Theodore Roosevelt National Park partnered with the University of Utah, Kansas State University, and Clemson University to launch this collaborative, multi-focal study encompassing a variety of perspectives and data-points. The focus of this paper is on research related to gateway communities surrounding the park. The purpose of this paper is to explore the usefulness of the appreciative inquiry (AI) methodology towards understanding gateway community views, goals, and connections with PPAs. Specifically, this study aims to:

- Understand the role of Theodore Roosevelt National Park related to stimulating regional tourism;

- Ascertain gateway communities’ perceptions of benefits from tourism as it relates to economic development and quality of life; and

- Explore nearby communities’ relationships with the park and how those communities may help influence quality visitor experiences, advance park goals, and develop partnerships.

In seeking to address these aims, we employ the AI methodology to synthesize community recommendations for park planning and development as they relate to each of the study goals. The following subsections present an introduction to the study setting and a review of literature relevant to these aims. Section 1.2 includes a brief literature review on gateway communities and draws connections between PPAs, gateway communities, and sustainable tourism development. Section 1.3 reviews the appreciative inquiry method utilized in this study and illustrates the usefulness of this method for sustainable tourism development.

1.1. Study Setting

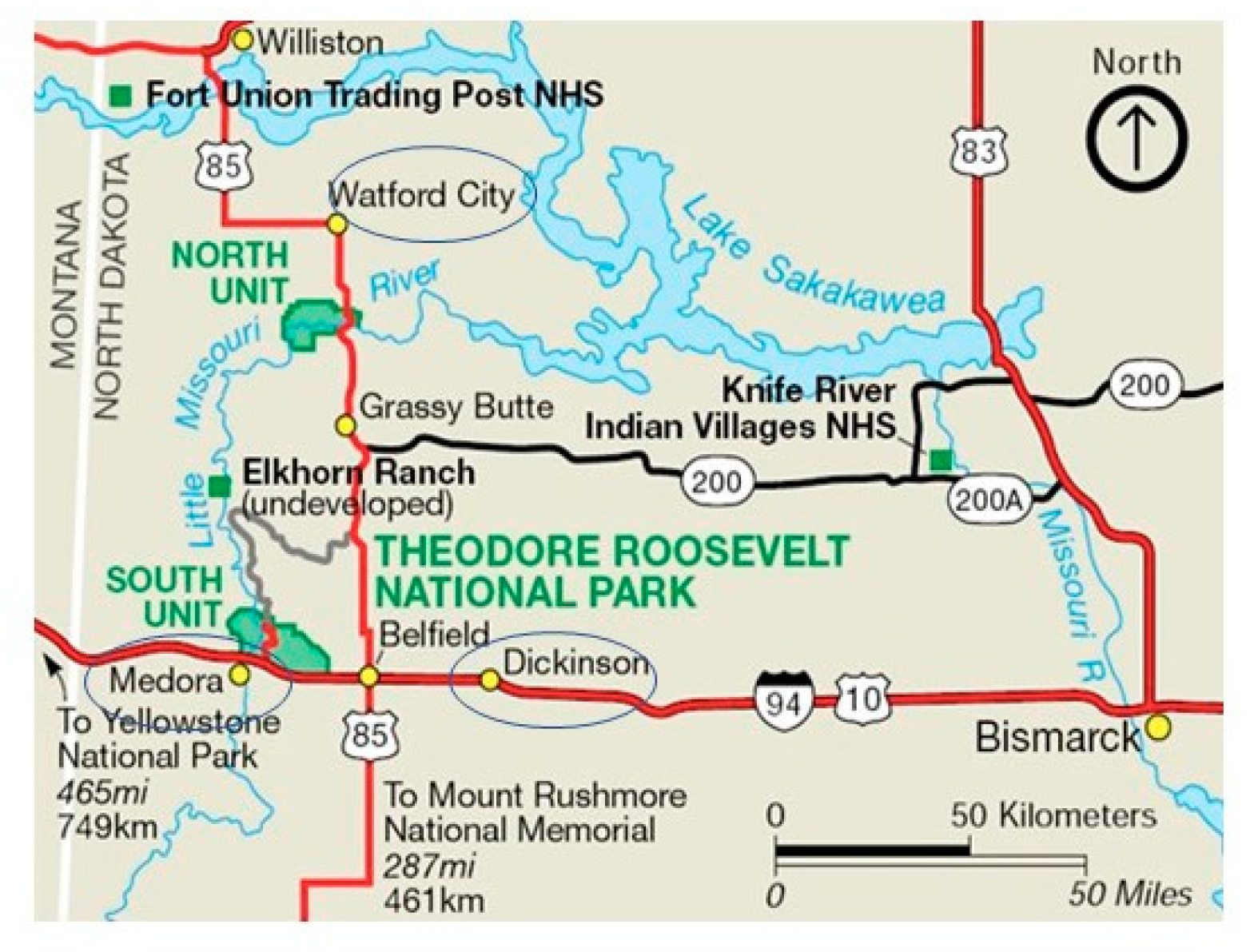

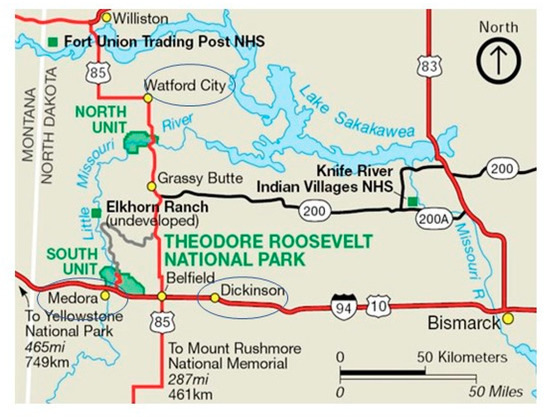

Theodore Roosevelt National Park spans 70,447 acres of North Dakota Badlands, stretching across the Northern Great Plains and the Little Missouri River. The park, which is divided into three separate units, is home to a variety of great plains flora and fauna and encompasses lands that are a part of the traditional bison hunting and eagle trapping grounds of the Hidatsa and Mandan tribes. The Arikara, Crow, Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Chippewa, Cree, Sioux, and Rocky Boy tribes are all associated with lands within the park [19].

The park was established in 1947 with the initial South Unit and Elkhorn Ranch Unit, and the addition of the North Unit followed in 1948. The park is charged with the mission of memorializing President Theodore Roosevelt and his commitment to American conservation [20]. The park is also situated atop the Bakken Formation, an extensive oil and natural gas reserve that is extensively accessed through hydraulic fracking, rendering oil and gas flares within sight of many park vistas [19].

Theodore Roosevelt National Park is accessed via the three primary gateway communities: Medora, Dickinson, and Watford City, ND (see Figure 1). Medora, founded in 1883, has a year-round population of about 130 residents [21] and welcomes several thousand visitors each year. Medora is North Dakota’s top tourism destination, where the majority of residents derive income from the industry [22]. The town boasts many old American West-themed attractions, including saloon-style restaurants, the North Dakota Cowboy Hall of Fame, the popular Medora Musical, and a Theodore Roosevelt impersonator. The town of Dickinson, founded in 1881, holds a population of around 23,000 people [21]. A full-service and residential community, Dickinson offers education, healthcare, museums, libraries, airport, and recreation centers. Watford City is home to about 7000 residents, a population that has more than tripled in the decade following the Bakken Oil Shale rush, which brought a massive influx of people and commerce to the area beginning around 2006 [23]. In the years following the rush, the city has invested extensively in infrastructure to create a high quality of residential life after the oil boom. Watford city also holds a variety of lodging and dining options and recognizes the park as a valuable community resource in quality of life for residents. Each community is unique yet intertwined with each other, the park, and the future development of the region.

Figure 1.

Theodore Roosevelt National Park Map [24].

1.2. Gateway Communities

Gateway communities are the doorways to PPAs. Gateway communities—also referred to as natural amenity communities—are communities that reside close to or share a border with a PPA and often provide visitor services. Also referred to as amenity communities, these communities are interwoven with PPAs, both shaping and being shaped by visitors. For example, gateway communities play an integral role in the PPA experience for many visitors. Gateway communities often provide the necessary or desired visitor services that PPAs cannot supply, including food and beverage services, gas and supply stations, entertainment, and overnight accommodations. Research suggests that visitors’ overall satisfaction of visiting a national park is linked to their experience in its gateway community [25]. This linkage makes PPA managers dependent, in part, on gateway communities to fulfill their recreation and visitor enjoyment mandates.

At the same time, gateway communities derive many benefits from PPAs, including financial, social, and environmental assets. Tourism development around PPAs often provides substantial economic opportunity for local communities [26,27,28,29]. Park and protected areas also provide a variety of ecosystem services and recreation opportunities that positively contribute to the character of the community and the quality of life for residents [28,30,31].

However, tourism can also have negative impacts on quality of life for gateway communities. For example, as over-visitation continues to be a significant issue facing national parks [32], nearby communities face challenges with increased traffic, crowding, and infrastructure stress [16,18,33,34]. Additionally, even though many rural areas in the American West derive more positive economic gain from tourism than extractive industries [35], contentions exist regarding the provision of lands for recreation, with opponents arguing that PPAs limit natural resources that could be used for industry and to generate jobs. This relates to a legitimate issue of benefit distribution. Within communities, local residents can be excluded from the benefits of PPA tourism or even harmed in the process of development [36,37,38,39].

A variety of factors shape the impact of PPA tourism development on gateway communities, many of which are also tied to the long-term development of a protected area. As PPA managers increasingly navigate encroaching development around their borders, mitigation strategies that mobilize communities as ambassadors for parks are much needed [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. This is certainly the case for Theodore Roosevelt National Park, which is situated within the Bakken Oil Formation and surrounded by gas and oil extraction operations. Due to these development pressures, NPCA ranks the park third in a list of parks most vulnerable to loss of cultural, economic, and natural assets in the face of environmental and land use policies enacted by the current executive branch administration [19]. Increased leasing of land bordering the park for drilling and hydraulic fracturing are imminent threats to viewsheds, air quality, dark skies, and visitor experiences [19]. As park administrators work to mitigate such threats, preserving strong relationships with gateway communities will prove critical. Likewise, as gateway communities seek to grow towards their respective missions, regional collaboration offers opportunities for each community to draw upon the assets of the park for sustainable tourism futures.

Collaboration is essential in enhancing the benefits of and minimizing the costs of tourism for both PPA managers and gateway community members. Increased communication between park managers and communities can help signal to managers which impacts are most critical for communities, such as pressings concerns like traffic and congestion [41]. Working with community members can also assist PPA managers in understanding local dialogues about and taking informed action on imminent threats to long-term sustainable development, such as climate change [42]. Researchers are presented with the opportunity to craft inquiries that not only understand but also encourage the development of strong relationships with residents, which ultimately empowers PPA managers to better protect and manage the lands they are charged with stewarding. While a variety of research tools have been employed to better understand gateway community perceptions of PPA development [43,44,45,46]. There remains a need for nuanced methods which captures community input on specific aspects of development unique to people and place.

1.3. Appreciative Inquiry

Appreciative inquiry is a change management approach poised to facilitate connections between conservation, livelihoods, and sustainable tourism development [47,48,49]. Appreciative inquiry was developed in 1985 by David Cooperrider & Srivesh Srivastva in a performance evaluation-based study in a healthcare facility setting [50,51]. The positive psychology-based approach of the framework uncovered a powerful tool for performance evaluation, and reportedly encouraged participants to denote and enact the positive aspects of their work as they reflected on it in the research process [52]. By participating in the AI process, researchers noted that participants were actually encouraged to act in accordance with the dreams and desires that were elucidated through the process. Subsequently, the method was utilized in a variety of settings, proving effective in business and hospitality [53,54,55], healthcare [56,57,58], and NGO management. The success of AI in NGO settings contributed to the adoption of the tool as an asset for community development [52].

This type of systematic discovery can breathe new life into public forums and meetings, initiating the design of participant destinies by and for themselves. AI has proved a useful tool for conducting work with rural communities [59], including those that serve as gateways to parks and protected areas [60,61]. The tool has also been particularly useful in the development of tourism [62], specifically sustainable tourism [48,63]. The method offers insight into community psychology [64], offering opportunities for meaningful, community-based participatory research partnerships [65].

Thirty years since its inception, the process of AI continues to be a positive change-making tool. Cooperrider [66] challenged those who would employ AI to consider that it is a malleable, ever-changing process, which draws strength from its co-constructive nature, encouraging researchers to consider how AI can contribute to visions of new possibilities and paradigms. It is in this spirit that the AI methodology was employed with gateway communities to Theodore Roosevelt National Park, with the goal of shaping co-constructed futures between the park and its people.

2. Methods

As a change management approach, AI informs the co-construction of knowledge relating to the relationships among conservation, livelihood, and sustainable tourism development. This approach elicits public participation in identifying positive qualities of people and place that make a destination unique, analyzes why these qualities work, and then builds on these qualities [47]. For this study, questions and methods were adapted from those used in a collaborative project between Arizona State University, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and gateway communities to Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument in southern Utah [47]. In following with this Grand Staircase pilot project, the present study employed a six-step appreciative inquiry approach:

- Initial Site Visit–Meeting with National Park Service (NPS) staff and visits to local communities (February 2017);

- Asset Mapping–Community assets documented in an extensive literature review. (Summer 2017);

- Appreciative Interviews and Surveys–Semi-structured interviews with key community members. Online surveys distributed via email and key contacts. (October 2017-April 2018);

- Mini-Appreciative Inquiry Sessions–Focus group held with each individual community. All community members invited. (Spring 2018);

- Global Sustainable Tourism Criteria Destination Evaluation–review of sustainability indicators (Fall 2018);

- Appreciative Inquiry Summit–Meeting open to community members in Medora, Dickinson, and Watford City, aimed at exploring opportunities for strengthening regional partnerships. (Spring 2019).

2.1. Data Collection: Community Resident Interviews and Surveys

Between October 2017 and April 2018, researchers completed a total of 21 interviews with key informants who resided or worked in one of the park’s three major gateway communities (Medora, Dickinson, and Watford City). Potential participants were identified by NPS staff, community leaders, and the University of Utah research team during the 2017 Community Asset Inventory process. The research team attempted to contact community members up to three times by telephone and email. Participants were asked to complete a semi-structured interview, which was expected to last approximately 30 minutes, with a total of 21 interviews completed. The structure of the interviews was adapted from Nyaupane and Timothy [47] and was used to inform the design of questions in the community engagement meetings aimed at uncovering assets through discovery, discussing goals as dreams, strategies for design, and long-term visioning as the destiny phase.

2.2. Community Survey

The research team recognized that not all community members in the three major gateway communities of the park could participate in the interviews and community meetings. Therefore, to maximize resident participation in the overall study, a community survey through an online platform (Qualtrics) was created. The survey remained open between October 2017 and April 2018 and was re-opened for final thoughts following the community summit in May 2019. The online survey was advertised in all three communities and at all three in-person community engagement meetings. A total of 53 residents began the survey, and 15 answered every question. The survey responses were used to support the findings from the community interviews and meetings.

2.3. Community Engagement In-Person Meetings

The primary data for this study derives from a series of community engagement meetings held in the gateway communities of Dickinson, Medora, and Watford City. The meetings were structured according to the Appreciative Inquiry process and specifically sought to assist the research team in accomplishing the overall research goals. A pilot meeting was hosted in Medora in October 2017 and informed the structure and outreach campaign for the subsequent three meetings held in April 2018.

To recruit community participants, the research team contacted members of the Convention and Visitors Bureau (CVB) and tourism offices in each community via email and telephone to discuss the most appropriate recruitment strategy for each community during the period from December 2017 to March 2018. Recruitment strategies included direct mail of two flyers and one reminder postcard to all Medora residents via the U.S. Post Office, press releases and print advertisements, web and social media advertisements, and additional community postings through local CVBs, public access television, radio stations, and signage. Finally, flyers and information were distributed via email to key contacts in each community.

Each community engagement meeting began with an introductory presentation from the research team to outline the research process and purpose. Following introductions, participants were seated at round tables with 6–10 people within each group. Each group was provided a flip chart and markers to record their input, identifying one community member to serve as a scribe. The research team then facilitated group collaboration by asking the semi-structured questions associated with the four phases of the AI method (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Semi-Structured Questions.

Each meeting concluded with individual groups sharing their top 3 major priorities or themes identified throughout the evening. In total, 54 community members participated in the meetings (Dickinson, 18; Medora, 19; and Watford City, 17). Gender represented across meetings was balanced, with a total of 25 men and 24 women identified via sign-in sheets. In addition, participants represented a wide range of professional occupations, including farmers, ranchers, tourism professionals, oil and energy workers, artists, clergy, business owners, local government officials, and retired residents.

2.4. Data Analysis

Because of the complexity of community aspirations and multi-dimensional components of community sense of place [67], “a more qualitative approach [offering] insight into aspects of human-environment interactions” [68] was necessary. As such, a sense of community relationships with the park was ascertained through the analysis of open-ended descriptions provided during our engagement with community members. Emergent themes were identified by community members themselves in these in-person engagement meetings. The semi-structured question protocol encouraged community members to collaboratively identify priorities relating to tourism assets and development. These priorities were reported utilizing flip charts, which were analyzed through thematic content analysis. Table 2. Includes examples of themes which were identified by residents in the data collection process and which served as the basis for the thematic content analysis.

Table 2.

Selected Community Engagement Group Data.

Thematic data from focus groups in each community were analyzed through thematic content analysis, which “provides a general sense of the information through repeated handling of the data,” and allows the researcher to understand a data set comprehensively “by living with it prior to any cutting or coding ([69]).” This process involves a five-step approach:

- (a)

- Familiarization with data (supplemented by preliminary phone and online interviews)

- (b)

- Generate initial codes (identified by both researchers and participants)

- (c)

- Review themes

- (d)

- Define and name themes

- (e)

- Produce the report

The process of generating categories or themes was done through analytic bracketing, a constructivist approach to meaning-making, which is focused on the “how’s and what’s of everyday life” and which “captures the interplay between discursive practice and discourses-in-practice ([70]).” In this process, the research team collaboratively noted regularities, identified recurring ideas or language and patterns, and examined the meanings for what they revealed about recurring features. Once classification systems were developed from the co-constructed data from the focus groups, researchers reviewed all of the emergent categories. Interview and survey data were also analyzed through analytic bracketing to supplement representativeness, and emergent themes from these additional data points were compared and synthesized with the themes from the focus groups. The emergence of themes was informed both by the data and by the researchers’ own understandings of the community as they developed over two years of community engagement with the study site through interviews, conversations, observations, and interactions within the park and its gateway communities. The researchers’ applied experiences with sustainable tourism development and gateway communities informed insight into the data and resulting identification of themes relating to the aims of the park’s strategic tourism development strategy. Recognition of the researchers’ positionalities within the research and the study communities strengthened the study’s employment of constructivist grounded theory which “assumes that neither data nor theories are discovered but instead are constructed by researchers as a result of their interactions with their participants and emerging analyses ([71]).” The utilization of thematic content analysis and analytic bracketing housed within the constructivist approach honored the synergistic nature and epistemological commitments of the appreciative inquiry process and uncovered a rich understanding of gateway community members’ dreams and desires related to the park. Thirteen themes relevant to the research goals were developed from the thematic data from focus groups, which was supplemented through data from interviews and online surveys. Table 3 provides a summary of emergent themes linked with associated study goals and data-driven recommendations.

Table 3.

Study Results.

3. Results

In the following section, the findings and themes of the study are detailed, with subthemes and specific examples of participant responses. A selection of actionable ideas for practical application of these findings to strengthen relationships with nearby communities is also included. Themes are presented below, organized by the primary goal to which they were connected, though it should be noted that many themes overlapped across multiple goals of the study. This thematic grouping allows for insights into emphases identified by community members as they related to three key types of relationships: the park’s relationship to regional tourism, community relationships with tourism, and relationships between the community and park itself.

Goal 1: Understand the role of Theodore Roosevelt National Park related to stimulating regional tourism

Theme 1. Communication: Enhanced understanding through regular, reoccurring face-to-face and print communication. In all communities, participants requested increased, ongoing communication between the park and their community. Participants reported a sense of feeling unaware of the programs and policy changes that were occurring in the park, and some participants believed that NPS staff were unaware of what was happening in gateway communities.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended the following actionable ideas to NPS staff: increase involvement in local government and stakeholder meetings in all three communities. Post regular updates on community events, volunteer opportunities, park events, and management decisions on community boards and local television channels in all three communities where applicable. Work with local newspapers to write regular press advisories on park events and management decisions.

Theme 2. Recreation development: Programs and opportunities to promote year-round recreation in the park and local communities. An emergent theme across communities included residents’ desire for more increased, varied, and year-round recreation opportunities. Medora residents expressed an interest in more hiking trails and were mainly concerned with keeping recreation activities affordable for all.

Theme 3. Resource management: Opportunities to improve resident understanding and input in park resource management decisions through education and communication. In both Medora and Dickinson, residents expressed a desire for the park to reduce Prairie dog populations and to more closely manage invasive plant species. This particular issue was related to community members’ concerns about encroachment onto adjacent private properties near the park’s boundaries. In Dickinson, meeting participants also expressed a desire to see a more detailed feral horse management plan. Additionally, these residents identified hunting as an essential cultural and tourist activity and would like to see policies in the community to prevent overhunting.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended the following actionable ideas to NPS staff: launch an education program to inform neighboring community residents about the natural management of prairie dogs and other species within the park borders. Identify a mechanism for community input into the development of a feral horse management plan. Continue cooperation and collaboration on management issues within and outside park boundaries (e.g., invasive species).

Theme 4. Strategic partnerships: Suggestions for collaborative partnerships between the park and community organizations to achieve shared goals. Community meeting participants identified a diverse collection of potential strategic partners to work with on realizing many of the goals mentioned throughout the visioning process. Medora residents suggested partnering with local authors to advance their goal of educating visitors about the history of the area. They also suggested that increased partnerships with the other gateway communities would strengthen tourism across the region. Medora residents also identified the CVB and the Chamber of Commerce as partners to launch local tours of the area.

Goal 2: Ascertain gateway communities’ perceptions of benefits from tourism as it relates to economic development and quality of life

Theme 5. Access: Year-round accessibility to and within the park for motorized and non-motorized recreationists. In all three meetings, participants discussed ideas for improved access to and within the park, including year-round road access, reduced access fees for locals and visitors, improved access to the Elkhorn Ranch Unit, and the establishment of a non-wilderness route that would allow continuous hiking and biking from Watford City to the park and connect the North and South Units.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended the following actionable ideas to NPS staff; Consider management adjustments to address seasonality and access to the park. Explore non-motorized opportunities through partnerships with communities to reach the park.

Theme 6. Community development: Infrastructure improvements to enhance citizen wellbeing and tourism opportunity. Generally, residents wanted projects that would improve infrastructure to support resident wellbeing and tourism. Medora residents desired more affordable housing that was needed to accommodate new year-round residents and seasonal employees. Watford City residents desired an increase in family housing and more resources to support families and community safety, such as improved internet access, a crisis shelter, and increased law enforcement. Participants in Dickinson commented on the need to attract new residents and tourists and suggested that strategies for attracting new residents included increased shopping opportunities, museum developments, and measures, such as ordinances and proper maintenance to protect existing neighborhoods and facilities within the community.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended that NPS staff continue supporting community action groups to address localized issues concerning infrastructure and growth.

Theme 7. Tourism management: Increased development of regional tourism that showcases local history and culture. Common to all community meetings was a continued emphasis on history and education. In Medora and Watford City, residents would like to foster the ‘Old West’ themed tour development and continue focusing on both Native American and cowboy culture. Residents in both Watford City and Medora also suggested a park shuttle as a useful tool to help alleviate traffic congestion during busy seasons. To accommodate continued tourism development, Medora business owners communicated the pressing need for increased availability of laborers, and the seasonal housing needed to support such workers.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended the following actionable ideas to NPS staff: explore options for transportation and infrastructure support, such as park shuttles. Partner with local authors to enhance storytelling efforts such as events, guided tours, and interpretation within the park.

Theme 8. Park development: Resident ideas to enhance park experiences through enhanced infrastructure, year-round access, programming, and educational materials. All participants in the study valued the park on some level; however, they had many ideas for developments within the park that could improve park experiences for locals and tourists. In both Medora and Watford City, residents strongly agreed that increased park ranger visibility would improve visitors’ experience. Increased signage, such as informational kiosks and trail markers, and extension of year-round amenities and programs were also desired.

Theme 9. Youth engagement: Strong desire to engage youth in communities and the park through partnerships, programming, and volunteerism. Participants in all communities expressed a strong desire for more youth-oriented activities and engagements. Dickinson residents specifically suggested integration with school curriculum, through field trips and library programs, as well as partnerships with the DSU Honors program. In Watford City, suggestions included leadership education, afterschool programs, and more community-based projects for youth to engage.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended the following actionable ideas to NPS staff: partner with educational institutions (such as DSU) to increase the use of and further align the existing park curriculum guides with state content standards. Explore the possibility of a Youth Ranger program. Engage students through signing up to leading guided hikes, volunteering to visit campsites and share information with visitors, or for clean-up events within the park.

Goal 3: Explore nearby communities’ relationship with the park and how those communities may help influence quality visitor experiences, advance park goals, and develop and leverage partnerships.

Theme 10. Citizen engagement: Opportunities to establish mutually beneficial partnerships through volunteerism. Community meeting participants felt that there was a need and opportunity to increase residents’ engagement with the park and their communities. Volunteerism was a prominent idea, and participants felt there would be interest in volunteer programs, such as an Adopt-a-Spot, trail, park, program or a community ambassador program that enabled residents to welcome new residents.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended that NPS staff work to increase mechanisms for the park and community-level partnerships and engagement. Example: park volunteer days (themed) and Adopt-a-Spot programs.

Theme 11. Community sense of place: Maintaining and developing the unique intangible characteristics unique to each community. Maintaining a positive community atmosphere was an essential theme in all communities. While similar, each community had a unique set of features that they would like to preserve and enhance. In Medora, residents were most proud of the small-town, family-oriented atmosphere and the focus on history within the community. Dickinson residents also appreciated their community’s small-town feel and stressed the preservation of local neighborhoods. Participants from Medora and Dickinson specifically requested local ordinances that support the preservation of their community atmosphere.

Theme 12. Conservation: Resident appreciation and desire for conservation programs to protect open space, viewsheds, and dark skies. In both Medora and Dickinson, view-shed and dark skies preservation was particularly important, and participants suggested establishing relevant educational programs and local ordinances.

Theme 13. Marketing: Individual and cross-promotional efforts to attract visitors to local communities, the park, and the region as a whole. Community members in all three meetings shared an expressed interest in increased marketing for the region, individual communities, and the park itself. In Medora, participants felt that emphasis on the walkability of the town would help to attract visitors. In Dickinson, participants suggested that a new park website would be a valuable marketing asset. Additionally, Dickinson participants were interested in cross-promoting the park, expressed a desire for the park to engage in an increased social media presence. Watford City community members suggested creating local marketing co-ops to cross-promote community businesses and attractions as well as the park.

In response to this emergent theme, we recommended the following actionable ideas to NPS staff: form a regional marketing taskforce. If possible, arrange for a park representative to sit in on the task force (while refraining from engaging in any paid marketing activities). Update the park website and consider adding links to community member pages where visitors can “Ask the Locals.”

4. Discussion

The collection of community-driven emergent themes allowed for the synthesize of data-driven recommendations related to resource access and tourism management, citizen and community engagement, conservation, marketing, and communication between the park and neighboring residents. These findings demonstrate the usefulness of the AI methodology to better understand nearby communities’ relationship to public lands and to facilitate managers’ abilities to support regional sustainable tourism development between PPAs and their gateway communities. The positive focus of the AI methodology provided a platform for both constructive and critical community dialogue. This inquiry has uncovered a great deal of community capacity for collaboration towards the co-construction of sustainable destinations, illuminating specific goals and needs related to each community and particular methods through which community members desire to support that growth.

Utilization of the AI methodology revealed that public input meetings related to more contentious areas of resource management have not functioned to provide tangible planning for mitigation strategies in the past. However, in this study, the unique framing of the AI process encouraged community members to focus on the future and to channel their energy into visioning for the future, encouraging participants to break away from understanding stakeholder meetings as forums to air grievances. This was quite relevant with regards to the resource management theme, which included community feedback related to the management of species such as prairie dogs and feral horses. Many community members hold passionate yet conflicting views related to visions for how the park should manage these species. Through focusing on dreams and desires, citizens vocalized how they could help the park implement management and communication tools to better include community voices in the management of feral horses. Community input meetings also provided park officials with an opportunity to communicate their work to responsibly manage species in the park, such as prairie dogs, which were the subject of participant concerns about encroachment into adjacent private properties near the park’s borders. Many residents held notions that the prairie dogs were spreading as an invasive species outside of the park boundaries, but education that occurred during the process informed residents that the populations of the animals were actually very concentrated within the park. This open dialogue helped community members to better understand the sustainable and science-based practices already in place and indicated opportunities for park rangers to educate community members about their ongoing species management planning. This type of open dialogue indicates areas where the park may leverage more communication platforms to inform residents about sustainable resource management.

This study also indicates the importance of community engagement in visitor use and planning studies. While literature indicates that Theodore Roosevelt National Park and other PPAS are under threat from encroaching development [19], this case of community-engaged research uncovered nuanced information specific to this location. Researchers learned from park officials about their efforts to preserve view-sheds and natural resources within a PPA that is surrounded by extractive industries. While hiking in the park at sunrise, we were also able to see first-hand the oil and gas flares burning in the distance. During community member meetings, we began to understand some of the intricacies of the communities that are deeply intertwined with these industries. As PPA managers move away from management strategies that view parks as islands [30], the necessity to add community collaboration to strategic planning processes is becoming increasingly important. This study indicates that the utilization of the AI method can aid in that process.

Another important lesson learned relates to differences in doing outreach with distinct communities. In these rural gateway communities, communication and recruitment efforts called for unique approaches for each area. For example, researchers learned that in Medora, direct mail through post office boxes was the most effective outreach methods. Yet in other gateway communities, placing advertisements in local papers and phone calls to community leaders were deemed most important. Each community has different channels for outreach and understanding who the key community leaders are to rally support for the meetings, especially in small or rural communities understanding this can be critical to the success of participant recruitment for research with gateway communities.

This study found that there was some overlap with findings that were strong across communities, but there were also unique attributes based on each community’s identity. We saw that tourism visions reflected different relationships with the park across the region. Wherein Medora is very tourism-driven, dreams and desires of its’ community were often related to infrastructural support for tourism growth such as housing and support of an extended shoulder season. Meanwhile, Dickinson is a community very interested in attracting visitors that will convert to residents, resulting in many suggestions derived from desires to design a more live-able and enjoyable community for residents. Finally, as Watford city continues to explore its own community identity following the Bakken oil shale rush, many suggestions from residents were tied to community outreach, recreation amenities, and rebranding from the negative outcomes associated with the man camps that once characterized this booming oil town.

5. Limitations and Future Research

Considering that PPAs are often national entities, engagement with local government and communities can be challenging. Yet, the more that PPA managers can engage with those communities, the better stewardship that can occur. When threats to conservation encroach upon PPA boundaries, community members can be park stewards, advocates, and educators. When community members are engaged and value the park as a resource, they can come to see PPAs as an aspect of quality of life and feel more connected to parks and excited to share them with visitors.

This study illustrates the advantages of the AI method to better connect with communities and to inform strategic sustainable tourism and recreation planning. We delimited the study to three primary gateway communities for the inquiry process. The selection of these three communities enabled researchers to focus on the most heavily populated and visited gateway communities to the park, yet did result in some reports of exclusion experienced by rural residents, outside these communities within the region. Additionally, this research is limited by the lack of inclusion of the voices of Native American communities throughout the research process. While the research team did express a desire to incorporate this into the present study, efforts to engage these communities were not included in the scope of this project as the park continues to navigate and establish a relationship with Indigenous leaders through its own separate initiatives. Additionally, we utilized different outreach methods across communities based on recommendations by community members, which may have provided further limitations regarding the representativeness of the findings.

Additionally, future research could examine mechanisms for community empowerment and institutional and political barriers to engagement. For example, Theme 13 revealed many community members’ desires to partner with the park on marketing, yet this is challenging as national parks are prohibited from engaging in paid marketing activities with specific businesses. Community empowerment initiatives have the potential to facilitate increased coordination and support for local marketing co-ops relevant to this theme. Theme 6 revealed shared desires regarding community development, which may be bolstered by future research into how PPA managers might support local community policies towards achieving those goals.

6. Concluding Insights

While PPAs must adhere to their own missions and policies, there remain opportunities to take on specific and unique relationships with gateways communities towards the end goal of better management and sustainable tourism development. PPAs are part of a region and therefore link to entities outside their borders. Future research which seeks to understand park management issues and engage gateway communities is an important aspect to create destination stewardship and facilitate a sense of community around these places. Knowing what community members value and how to enhance recognition for their values within the public land entities is an important consideration. The appreciative inquiry methodology aids researchers and PPA managers in creating a scenario of solidarity towards the end goal of sustainable destination planning. This study positions engagement with gateway communities as an asset to PPA managers and illustrates strengths and partnership potential with individual communities. In this study, each particular gateway community articulated unique visions for the future and sustainable tourism development. Though these communities shared some commonalities, each identified unique community characteristics, motivations, and development goals. This inquiry reveals diverse perspectives across the communities situated along the shared boundary of the park. These perspectives illuminate the potential for diversity of support and a fostering of partnerships in pursuit of sustainable tourism and conservation strategies. These findings emphasize the necessity to engage with and learn from gateway communities towards a better understanding of the strengths and varying capacities for PPA stewardship within and beyond the political and institutional boundaries of the park.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.B.; data curation, K.S.B.; formal analysis, L.J., N.Q.L. and K.S.B.; funding acquisition, K.S.B.; investigation, L.J., N.Q.L. and K.S.B.; methodology, KS.B.; project administration, K.S.B.

Funding

This research was funded by Kansas State University: S17172.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dinica, V. The environmental sustainability of protected area tourism: Towards a concession-related theory of regulation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushell, R.; Eagles, P.F. (Eds.) Tourism and Protected Areas: Benefits beyond Boundaries: The Vth IUCN World Parks Congress; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bushell, R.; Bricker, K. Tourism in protected areas: Developing meaningful standards. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 17, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushell, R.; McCool, S.F. Tourism as a tool for conservation and support for protected areas: Setting the Agenda. In Tourism and Protected Areas: Benefits beyond Boundaries: The Vth IUCN World Parks Congress; Bushell, R., Eagles, P.F., Eds.; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Epler Wood, M. Sustainable Tourism on A Finite Planet: Environmental, Business, and Policy Solutions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Woo, E.; Singal, M. The tourist area life cycle (TALC) and its effect on the quality-of-life (QOL) of destination community. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 423–443. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.; Newsome, D.; Moore, S. Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management; Channel View: Clevedon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Park Service. National Environmental Policy Act Handbook. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nepa/upload/NPS_NEPAHandbook_Final_508.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- Pomeranz, E.F.; Needham, M.D.; Kruger, L.E. Stakeholder perceptions of collaboration for managing nature-based recreation in a coastal protected area in Alaska. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2013, 31, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pinel, S.L.; Pecos, J. Generating Co-Management at Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument, New Mexico. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, C.; Manseau, M.; Mouland, G.; Brown, A.; Nakashuk, A.; Etooangat, B.; Nakashuk, M.; Siivola, D.; Kaki, L.M.; Kapik, A.; et al. Co-operative management of Auyuittuq National Park: Moving towards greater emphasis and recognition of Indigenous aspirations for the management of their lands. In Indigenous Peoples’ Governance of Land and Protected Territories in the Arctic; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Petrzelka, P.; Marquart-Pyatt, S. “With the Stroke of a Pen”: Designation of the Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument and the Impact on Trust. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H.; Leahy, J.E.; Jakes, P.J. Reflections from USDA Forest Service employees on institutional constraints to engaging and serving their local communities. J. For. 2007, 105, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.B. The social responsibilities of environmental groups in contested destinations. Tour Recreat. Res. 1999, 24, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, R.D.; Harrington, L.M. Understanding agents of change in amenity gateways of the Greater Yellowstone region. Community Dev. 2018, 49, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, A.E. Impacts of transit in national parks and gateway communities. Transp. Res. Rec. 2005, 1931, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, M.J.; Gagnon, C. An assessment of social impacts of national parks on communities in Quebec, Canada. Environ. Conserv. 1999, 26, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.; Beckley, T.; Wallace, S.; Ambard, M. A picture and 1000 words: Using resident-employed photography to understand attachment to high amenity places. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 36, 580–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Parks Conservation Association. Spoiled Parks: The 12 National Parks Most Threatened by Oil and Gas Development. Available online: https://www.npca.org/reports/oil-and-gas-report (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- National Park Service. Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Foundation Document: 2014. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/thro/learn/management/upload/Theodore-Roosevelt-National-Park-Foundation-Document-2014.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/en.html (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Medora Convention and Visitors Bureau. Medora, North Dakota. Web. Available online: https://www.medorand.com/ (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Nicas, J. Oil Fuels Population Boom in North Dakota City. Wall Str. J. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304072004577328100938723454?mod=googlenews_wsj (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- National Park Service. Theodore Roosevelt National Park Maps. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/thro/planyourvisit/maps.htm (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Lee, D.; Reeder, D. Mitigating encroachment of park experiences: Sustainable tourism in gateway communities. Park Sci. 2012, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker, K.S.; Black, R. Sustainability in Adventure Programming: Maximizing Benefits for Cultural Preservation, Nature Conservation, and Local Resident’s Well-being. In Adventure Programming and Travel in the 21st Century; Black, R., Bricker, K.S., Eds.; Venture Publishing: State College, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 459–497. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, R.; Horan, E.; Tozzi, L. The importance of sustainable tourism in reversing the trend in the economic downturn and population decline of rural communities. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2014, 12, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.; McCool, S.F. Tourism in National Parks and Protected Areas: Planning and Management; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rasker, R. Montana’s Economy, Public Lands, and Competitive Advantage. Available online: https://headwaterseconomics.org/economic-development/trends-performance/montanas-economy-and-protected-lands/ (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Keiter, R.B. To Conserve Unimpaired: The Evolution of the National Park Idea; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L.K.; Shaw, W.W.; Schelhas, J. Urban neighbors’ wildlife-related attitudes and behaviors near federally protected areas in Tucson, Arizona, USA. Nat. Areas J. 1997, 17, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Timmons, A. Too Much of a Good Thing: Overcrowding at America’s National Parks. Notre Dame Law Rev. 2018, 94, 985–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Marquit, J.D.; Mace, B.L. Park visitor and gateway community perceptions of mandatory shuttle buses. In Sustainable Transportation in Natural and Protected Areas; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gregor, S.; Koithan-Louderback, K. Marketing a resort community: Estes Park at a precipice. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1997, 38, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorah, P.; Southwick, R. Environmental Protection, Population Change, and Economic Development in the Rural Western United States. Popul. Environ. 2003, 24, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matose, F.M. Local People’s Uses and Perceptions of Forest Resources: An Analysis of a State Property Regime in Zimbabwe. Master’s Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaiwa, J.E.; Stronza, A.L. The effects of tourism development on rural livelihoods in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakka, R.; Cottrell, S.P.; Siikamäki, P. Sustainability perspectives on Oulanka National Park, Finland: Mixed methods in tourism research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 480–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.M.; Prideaux, B. Indigenous ecotourism in the Mayan rainforest of Palenque: Empowerment issues in sustainable development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, S.L. Operationalising both sustainability and neo-liberalism in protected areas: Implications from the USA’s National Park Service’s evolving experiences and challenges. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1848–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, M.; Lamp, M.; Palang, H. Tourism Impacts and Local Communities in Estonian National Parks. Scan. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 11 (Suppl. 1), 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonzanigo, L.; Giupponi, C.; Balbi, S. Sustainable tourism planning and climate change adaptation in the Alps: A case study of winter tourism in mountain communities in the Dolomites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.; Lemelin, R.; Koster, R.; Budke, I. A capital assets framework for appraising and building capacity for tourism development in aboriginal protected area gateway communities. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keske, C.; Smutko, S. Consulting communities: Using audience response system (ARS) technology to assess community preferences for sustainable recreation and tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauman, E.; Banks, S. Gateway community resident perceptions of tourism development: Incorporating Importance-Performance Analysis into a Limits of Acceptable Change framework. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salk, R.; Schneider, I.E.; McAvoy, L.H. Perspectives of sacred sites on Lake Superior: The case of Apostle Islands. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2010, 6, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.; Timothy, D. Linking Communities and Public Lands through Tourism: A Pilot Project; Technical Report; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Che Aziz, R. Appreciative inquiry: An alternative re-search approach for sustainable rural tourism development. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2013, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.; Whitney, D.D.; Stavros, J.M. The Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change, 2nd ed.; Berrett-Koehler, B.K., Ed.; Crown Custom Pub: Brunswick, OH, USA; San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.; Srivastava, S. Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In Research in Organizational Change and Development: An Annual Series Featuring Advances in Theory, Methodology, and Research; Woodman, R.W., Pasmore, W.A., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.; Barrett, F.; Srivastva, S. Social Construction and Appreciative Inquiry: A Journey in Organizational Theory. In Management and Organization: Relational Alternatives to Individualism; Hosking, D.H., Dachler, P., Gergen., K.J., Eds.; Avebery: Aldershot, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, D.; Trosten-Bloom, A. The Power of Appreciative Inquiry: A Practical Guide to Positive Change, 2nd ed.; BK Business Book; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, D.; Hanson, B. The resilience of appreciative inquiry allies: Business education sustains the business community. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2017, 17, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P. A Critical Appreciation of Appreciative Inquiry in the Advance of Sustainable Business. Build Sust. Leg 2015, 5, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, T. Appreciative Inquiry and Hospitality Leadership. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovski, S.; Schmied, V.; Vickers, M.; Jackson, D. Using appreciative inquiry to transform health care. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 45, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangarakis, S. Appreciative Inquiry in Healthcare: Positive Questions to Bring Out the Best. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2012, 26, 229. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G.; Machon, A. Appreciative Healthcare Practice: A Guide to Compassionate, Person-Centred Care; M & K Update: Keswick, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781905539932. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane, G.; Poudel, S. Application of appreciative inquiry in tourism research in rural communities. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R.; Lemelin, R. Appreciative Inquiry and Rural Tourism: A Case Study from Canada. Tour. Geogr. 2009, 11, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdarwati, G.A. Appreciative inquiry for community engagement in Indonesia rural communities. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, M.E.; Hall, M.C. The Potential for Appreciative Inquiry in Tourism Research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiner, S.; Stewart, E.; Lama, L. Assessing the Effectiveness of ‘Appreciative Inquiry’ (AI) in Nepali Pro-Poor Tourism (PPT) Development Processes. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.; Bright, D. Appreciative inquiry as a mode of action research for community psychology. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 35, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, C.; Peters, R.; Parkhurst, M.; Beck, L.; Hui, B.; May, V.; Tanjasiri, S. Enhancing Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships Through Appreciative Inquiry. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2015, 9, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperrider, D. The gift of new eyes: Personal reflections after 30 years of appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Res. Organ. Behav. Dev. 2017, 25, 81–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, R. Multidimensional community and the Las Vegas experience. GeoJournal 2015, 80, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishwick, L.; Vining, J. Toward a Phenomenology of Recreation Place. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, M.; Major, C.H. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780415674799. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J. Advancing a constructionist analytics. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; MRSV: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 411–443. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R.; Keane, E. Evolving Grounded Theory and Social Justice Inquiry. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Routledge: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 411–443. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).