Maximising the Edges of Natural and Human Systems: The Case for Sociotones

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

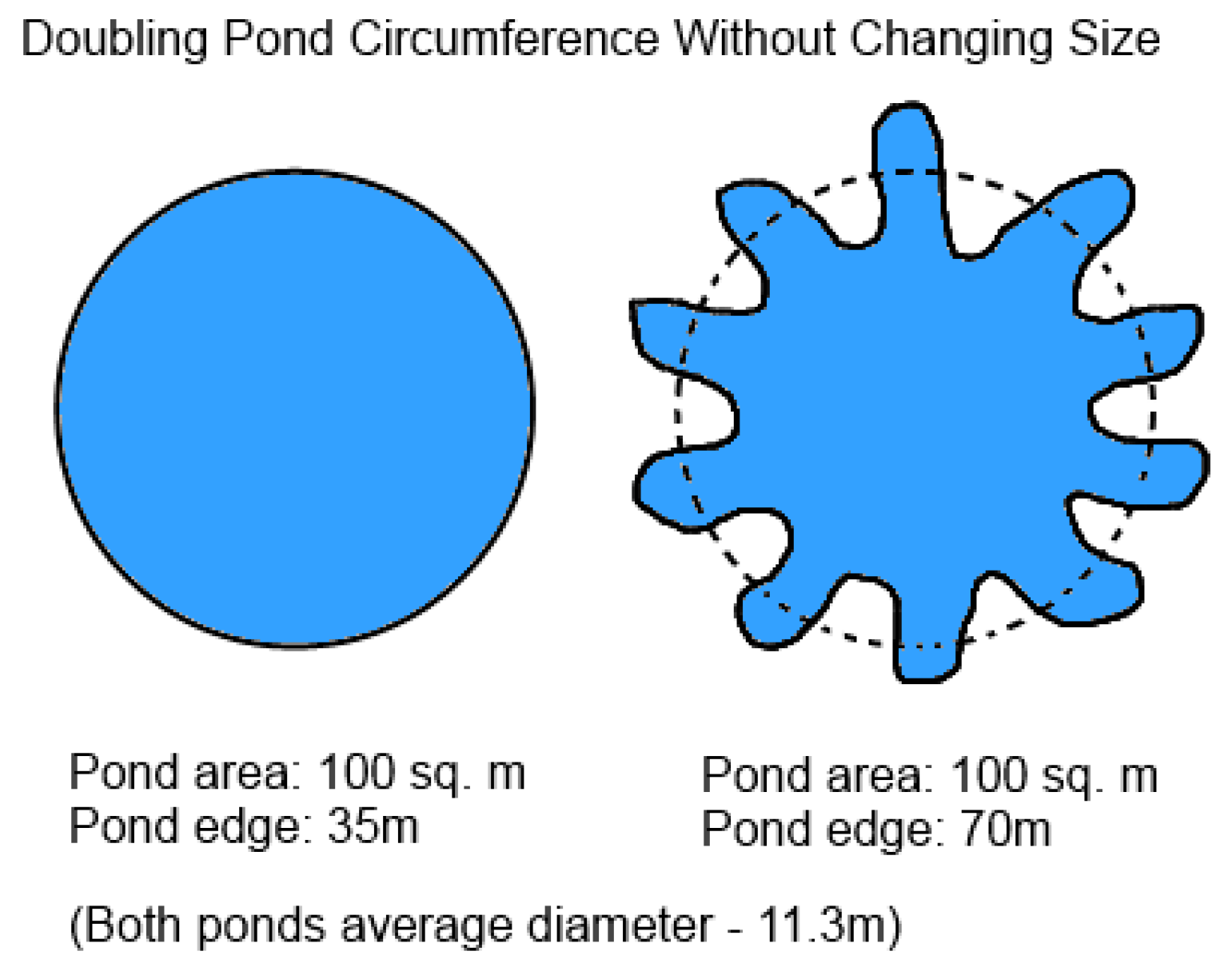

Just as it is possible to maximise the edges, diversity and productivity between neighbouring biological communities, so it is possible to create a more significant edge effect in society between different social groupings with diverse worldviews, power structures and intentions.

2.1. A Sociotone is a Field of Increased Diversity

2.2. A Sociotone is Part of the Whole and Evolves as the Whole Evolves

2.3. Sociotones Range from High Incompatibility to Adaptability

2.4. Sociotones Manifest High Levels of Uncertainty and Choice

2.5. Sociotones Offer the Prospect of Serendipity and Innovation

3. Results

3.1. The Context

3.2. Case Study

- (i)

- Society: enhancing solidarity between migrants and welcome communities, encouraging collaborative decision-making, developing capacities for future scenario planning, acquiring tools for conflict facilitation, sharing and supporting local traditions.

- (ii)

- Environment: understanding the impact and developing resilience to climate change in food, land, biodiversity and water systems, bringing culture back to agri-culture, appreciation of the diversity of cultural influences on food patterns.

- (iii)

- Economy: enhancing ethical, fair and transparent business relations, increasing autonomy from the agro-industrial system, promoting viable livelihoods and socio-entrepreneurship, bridging the gap between producers and consumers.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clements, F.E. Research Methods in Ecology; University of Nevada, Lincoln: Reno, Nevada, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Horpe, D. The Importance of Ecotones. Available online: https://www.eoi.es/blogs/davidthorpe/2014/01/16/the-importance-of-ecotones/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Burton, M.; Kagan, C. Edge Effects, resource utilisation and community psychology. In Proceedings of the III European Conference on Community Psychology, Bergen, Norway, September 2000; Available online: http://www.compsy.org.uk/BERGEN.PDF (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Temple, S.A.; Flaspohler, D.J. The Edge of the Cut: Implications for Wildlife Populations. J. For. 1998, 96, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Odum, E.P. Fundamentals of Ecology, 3rd ed.; W. B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mollison, B.C. Permaculture a Practical Guide for a Sustainable Future; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, A. Game Management; Charles Schribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, S. Ecotones and Edges: Explaining Abrupt Changes in Ecosystems. Available online: https://eco-intelligent.com/2016/12/15/ecotones-and-edges-explaining-abrupt-changes-in-ecosystems/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Seidman, P. Vitality at the Edges Ecotones and Boundaries in Ecological and Social Systems. World Future Rev. 2009, 1, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senft, A.R. Species Diversity Patterns at Ecotones; University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, M.M.; Burger, L.W., Jr.; Martin, J.A. The Law of Interspersion and the Principle of Edge: Old Arguments and a New Synthesis. Natl. Quail Symp. Proc. 2017, 8, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Guthery, F.S.; Bingham, R.L. On Leopold’s principle of edge. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1999, 20, 240–344. [Google Scholar]

- Maarel, E.v.d. Ecotones and ecoclines are different. J. Veg. Sci. 1990, 1, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M. Ecotone Classification According to its Origin. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2003, 6, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar]

- Engels, J. Why Is the Edge so Damned Important? The Permaculture Research Institute: The Channon, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://permaculturenews.org/2015/10/16/why-is-the-edge-so-damned-important/ (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Holmgren, D. Permaculture Principles & Pathways beyond Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Permanent Publications: East Meon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mang, P.; Reed, B. Designing from place: A regenerative framework and methodology. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C. A New Theory of Urban Design; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, B. Shifting from ‘sustainability’ to regeneration. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, P.; McCabe, J.T. Response Diversity and Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. Curr. Anthropol. 2013, 54, 114–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gast, L.; Patmore, A. Mastering Approaches to Diversity in Social Work; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Respect for Diversity. Module 3: Individual Peacekeeping Personnel, UN Core Pre-Deployment Training Materials; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Principles for a New Urban Agenda. World Cities Report. Chapter 9. Available online: http://wcr.unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Chapter9-WCR-2016.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Soja, E. Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I. M. Inclusion and democracy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. Jane Jacobs: The Last Interview and Other Conversations; Melville House Publishing: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dreu, C.K.W.D.; Vliert, E.V.D. Using Conflict in Organizations; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, D. Wholeness and the Implicate Order; Routledge: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, T.; Marvick, V. Patterning as Process. Permac. Act. 1998, 39, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, D.C. Design for Human and Planetary Health—A Holistic/Integral Approach to Complexity and Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, Centre for the Study of Natural Design, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Regenesis Group. The Regenerative Practitioner. Systemic Frameworks; Regenesis Group, Inc.: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time. Harper Perenn. Mod. Thought 1927. reprint. [Google Scholar]

- Wszelaki, A.; Broughton, S. Trap Crops, Intercropping and Companion Planting. W235-F, Extension; The University of Tennessee, Institute of Agriculture: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scand. Political Stud. 2007, 30, 137–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, A.; Velayutham, S. Everyday Multiculturalism; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston-Zimmerman, K. Urban Planning Has a Sexism Problem, Next City. 2017. Available online: https://nextcity.org/features/view/urban-planning-sexism-problem (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Shannon, C. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, C.R.; Calabrese, R.J. Some Explorations in Initial Interaction and Beyond: Toward a Developmental Theory of Interpersonal Communication. Hum. Commun. Res. 1975, 1, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.K.; Caruso, T.; Buscot, F.; Fischer, M.; Hancock, C.; Maier, T.S.; Meiners, T.; Mueller, C.; Obermaier, E.; Prati, D.; et al. Choosing and using diversity indices: Insights for ecological applications from the German Biodiversity Exploratories. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 3514–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merton, R.K.; Barber, E. The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lasry, J.M. Serendipity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Denrell, J.; Fang, C.; Winter, S.G. The economics of strategic opportunity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melo, R.M.C. On Serendipity in the Digital Medium towards a Framework for Valuable Unpredictability in Interaction Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Koestler, A. The Act of Creation; Hutchinson & Co.: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR). Figures at Glance, Field Information and Coordination Section. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Ionesco, D. Let’s Talk about Climate Migrants, not Climate Refugees. IOM. Available online: https://migrationdataportal.org/blog/lets-talk-about-climate-migrants-not-climate-refugees/ (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNCHR. Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees. Resolution 2198 (XXI) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. 1951. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ProtocolStatusOfRefugees.aspx (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Steavenson, W. Our Island Is Like a Mosaic’: How Migrants are Reshaping Sicily’s Food Culture. The Guardian. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/17/our-island-is-like-a-mosaic-how-migrants-are-reshaping-sicilys-food-culture (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- D’Angelo, A. Italy: The ‘illegality factory’? Theory and practice of refugees’ reception in Sicily. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 2213–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM. Human Trafficking through the Central Mediterranean Route: Data, Stories and Information Collected by the International Organization for Migration; The UN Migration Agency, Ministry of the Interior through the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF): Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti, B. The European Safe Country of Origin List: Challenging the Geneva Convention’s Definition of Refugee? Reset- Dialogues on Civilizations, Milan, Italy. 2016. Available online: https://www.resetdoc.org/story/the-european-safe-country-of-origin-list-challenging-the-geneva-conventions-definition-of-refugee/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- UNICRI. Trafficking of Nigerian Girls in Italy. The Data, the Stories, the Social Services; United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute: Turin, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Licata, M.; Tuttolomondo, T.; Leto, C.; Virga, G.; Bonsangue, G.; Cammalleri, I.; Gennaro, M.C.; La Bella, S. A survey of wild plant species for food use in Sicily (Italy)—results of a 3-year study in four Regional Parks. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- East, M. The Future is Multicultural: Regenerative Solutions from Sicily, The Scotsman 2017. Available online: https://www.scotsman.com/news/opinion/may-east-sicily-punches-above-its-weight-on-the-world-stage-1-4150772 (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- Médail, F.; Quézel, P. Biodiversity hotspots in the Mediterranean Basin: Setting global conservation priorities. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 1510–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SINAB. Italian Organics. Italian Information System on Organic Agriculture; Italian Ministry of Agriculture (MiPAAF): Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, D.G. Agricultural Sicily. In Economic Geography; 1941; Volume 17, pp. 109–120. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/141140?seq=1 (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- European Commission, Growth, Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Sicily. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regional-innovation-monitor/base-profile (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- European Parliament. What Europe Does for Me. My Region, Sicily. Available online: https://what-europe-does-for-me.eu/en/portal/1/ITG1 (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- European Union. Unemployment Statistics. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics explained/pdfscache/1163.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Partnerships Platform. Sicilia Integra—Socio-Economic Integration of Migrants and Unemployed Youth through Agro-Ecology and Sustainable Community Design. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=11763 (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Banulescu-Bogdan, N.; Fratzke, S. Europe’s Migration Crisis in Context: Why Now and What Next? Migration Police Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sirius Policy Network. A Clear Agenda for Migrant Education in Europe, Migration Policy Group. 2014. Available online: http://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Agenda-and-Recommendations-for-Migrant-Education.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Kokotsaki, D.; Menzies, V.; Wiggins, A. Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improv. Sch. 2016, 19, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Buckler, C.; Creech, H. Shaping the Future We Want. UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005–2014; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, The Gender Snapshot 2019. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2019/09/progress-on-the-sustainable-development-goals-the-gender-snapshot-2019 (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- UNESCO. Sustainable food project gives vulnerable migrant women a new start. 2019. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/news/sustainable-food-project-gives-vulnerable-migrant-women-new-start (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- United Nations for Refugees and Migrants. The New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. 2016. Available online: https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/declaration (accessed on 7 May 2019).

- The Government Office for Science. Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change Final Project Report, London. 2011. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287717/11-1116-migration-and-global-environmental-change.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- United Nations Development Programme. Development Approaches to Migration and Displacement. Key Achievements, Experiences and Lessons Learned 2016–2018 UNDP Technical Working Group on Migration and Displacement, Global Report 2018. Available online: https://www.no.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/prosperity/economic-recovery-mobility/Development_Approaches_to_Migration_and_Displacement_2016-2018.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Box, G.E.P. Science and Statistics. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1976, 71, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System A | System B | |

|---|---|---|

| No difference in stability, yields or growth | 0 | 0 |

| One system benefits at the expense of the other | + | - |

| One system benefits at the expense of the other | - | + |

| Both systems benefit | + | + |

| Both are decreased in vitality | - | - |

| One system benefits, the other is unaffected | + | 0 |

| One system benefits, the other is unaffected | 0 | + |

| One is decreased the other is unaffected | - | 0 |

| One is decreased the other is unaffected | 0 | - |

| Level of Hegemony | Level of Diversity | Compatibility | |

|---|---|---|---|

| + | - | + | Putnam perspective |

| - | + | - | Putnam perspective |

| - | ++ | +++ | Sociotone proposition |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

East, M. Maximising the Edges of Natural and Human Systems: The Case for Sociotones. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247203

East M. Maximising the Edges of Natural and Human Systems: The Case for Sociotones. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247203

Chicago/Turabian StyleEast, May. 2019. "Maximising the Edges of Natural and Human Systems: The Case for Sociotones" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247203

APA StyleEast, M. (2019). Maximising the Edges of Natural and Human Systems: The Case for Sociotones. Sustainability, 11(24), 7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247203