Agroecology as a Practice-Based Tool for Peacebuilding in Fragile Environments? Three Stories from Rural Zimbabwe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Issue: Agroecology, Peacebuilding and Changing Social–Ecological Relationships in Zimbabwe

2.1. Agroecology and Peacebuilding

2.2. Authoritarianism and Technocratic Developmentalism in Zimbabwe

2.3. A Context of Politicised Livelihoods and Contested Entitlements

2.4. Agroecology and Social Farming in Zimbabwe

3. Methods

4. Research Findings

4.1. Dema Community

When there’s work in your field—but you can’t afford with your family, then you call ilima so that people can come and help—they can come with their ideas. That’s when you get information … because when we do ilima we buy beer. So when people are wise they start to talk. Even hidden things. When he’s wise now - when he takes wise water—he starts to share—‘you know my friend, I’ve got something very precious’—like seed![64]

4.2. Mhototi Community

4.3. Chikukwa Community

‘If there was some food aid—out of 20 bags I’d grab five—I could take it ‘cause I’m the leader. I didn’t know that there is a sense of greed in us that you might not notice—you just think it’s your right. I was such an angry person … I used to even beat my children. That stick that I beat my child with, what kind of pain was I causing my child?’[67]

‘I was a very hard man. Since I’m a [headman] people must respect me …I’m a big traditional man. I’m second to the chief! People were afraid of me. But here, I learned that everyone is the same—everyone should be respected. And by so doing, I now manage to talk to everybody. Now I am a better leader.’[68]

4.4. Intersections between Resilience, Agency and Peace

‘So suspicion in is very high. Yesterday we were talking about forming these groups—I was trying to tell them about avoiding mistrust - so that they can form groups for bargaining purposes. Having a rep will benefit you. …When we are looking at the organic [farmers], they are more on the ground. They feel like they are more accommodated by each other. They share their ideas. They come together. There is that unity of purpose. When it comes to these competitions, it’s conventional [farmers] that thrive there. But with the organic farmers, it’s like a community—they come together. That is my observation—they work together so they tend to be closer. They depend upon each other to build their assets. …The conventional farmers don’t do that.’[71]

5. Discussion: Reforging Social–Ecological Relationships for Peace Formation

5.1. Agency for Resilience

5.2. Transforming Relationships through Collective Endeavour

5.3. Implications for Building a Just Peace

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Scoones, I.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M., Jr.; Hall, R.; Wolford, W.; White, B. Emancipatory rural politics: Confronting authoritarian populism. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 45, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fund for Peace. Fragile States Index. 2018. Available online: http://fundforpeace.org/fsi/ (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- Homer-Dixon, T.F. Environment, Scarcity and Conflict; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Trottier, J. Water Wars: The Rise of a Hegemonic Concept. Exploring the Making of the Water War and Water Peace Belief within the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict; PCCP Series 6.8; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Asaf, Z.; Schoenfeld, S.; Alleson, I. Environmental Peacebuilding Strategies in the Middle East: The Case of the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies. Peace Confl. Rev. 2010, 5, 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhendler, I.; Dinar, S.; Katz, D. The politics of unilateral environmentalism: Cooperation and conflict over water management along the Israeli-Palestinian border. Glob. Environ. Politics 2011, 11, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckles, D.; Rusnak, G. Conflict and Collaboration in Natural Resource Management; The International Research Development Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.; Rutagarama, E.; Cascao, A.; Gray, M.; Chhotray, V. Understanding the co-existence of conflict and cooperation: Transboundary ecosystem management in the Virunga Massif. J. Peace Res. 2011, 48, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, S.H. Transboundary Conservation and Peacebuilding: Lessons from Forest Conservation Biodiversity Project; UNU-IAS Policy Report; United Nations University: Trigo, Macau, April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bohle, H.G.; Fünfgeld, H. The political ecology of violence in eastern Sri Lanka. Dev. Chang. 2007, 38, 665–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, N.L.; Watts, M. Violent Environments; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kriger, N.J. The Zimbabwean war of liberation: Struggles within the struggle. J. South. Afr. Stud. 1988, 14, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranger, T.O. Voices from the Rocks. Nature, Culture and History in the Matopos Hills of Zimbabwe; James Currey: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J. Things fall apart, the centre can hold: Processes of post-war political change in Zimbabwe’s rural areas. Occas. Pap. 2014, 8, 131–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. Do ‘Zimbabweans’ Exist? Trajectories of Nationalism, National Identity Formation and Crisis in a Postcolonial State; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Newsham, A.; Kohnstamm, S.; Otto Naess, L.; Atela, J. Agricultural Commercialisation Pathways: Climate Change and Agriculture; APRA Brief 6; Future Agricultures Consortium: Brighton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, J. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. J. Peace Res. 1969, 6, 167–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Uphoff, N. Opportunities for Raising Yields by Changing Management Practices: The System of Rice Intensification in Madagascar. In Agroecological Innovations. Increasing Food Security with Participatory Development; Uphoff, N., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate, G.; Guzman, S. Transformative Agroecology: Foundations in Agricultural Practice, Agrarian Social Thought, and Sociological Theory. In Agroecology: A Transdisciplinary, Participatory and Action-Oriented Approach; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, C.G.; Lieblein, G.; Gliessman, S.; Breland, T.A.; Creamer, N.; Harwood, R.; Salomonsson, L.; Helenius, J.; Rickerl, D.; Salvador, R.; et al. Agroecology: The ecology of food systems. J. Sustain. Agric. 2003, 22, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Ward, H. Social Capital and the Environment. World Dev. 2001, 29, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S. Agroecology: Growing the roots of resistance. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, E. The Inner Limits of Mankind: Heretical Reflections on Today’s Values, Culture and Politics; One World: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K.E. Three Faces of Power; Sage Publications International Educational and Professional Publisher: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Karlberg, M. The Power of Discourse and the Discourse of Power: Pursuing Peace through Discourse Intervention. Int. J. Peace Stud. 2005, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise: The Latin American Modernity/Coloniality Research Program. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Berkes, F. Adaptive comanagement for building resilience in social–ecological systems. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, D. People, Peace, and Power: Conflict Transformation in Action; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach, J.P. The Little Book of Conflict Transformation: Clear Articulation of the Guiding Principles by a Pioneer in the Field; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MacGinty, R. Where is the Local? Critical Localism and Peacebuilding. Third World Q. 2015, 36, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, O.P. Failed Statebuilding versus peace formation. Coop. Confl. 2011, 48, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Giménez, E.; Shattuck, A. Food crises, food regimes and food movements: Rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 109–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Wals, A.; Kronlid, D.; McGarry, D. Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A. Emancipating Transformations: From Controlling ‘the Transition’ to Culturing Plural Radical Progress; STEPS Working Paper 64; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, L.R. What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and Thought. Book Discussion. 2015. Available online: http://www.c-span.org/video/?325752-1/lewis-gordon-fanon-said (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- Alexander, J. The Unsettled Land. State-Making and the Politics of Land in Zimbabwe 1893–2003; James Currey: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stocking, M.A. Relationship of agricultural history and settlement to severe soil erosion in Rhodesia. Zambezia 1978, 6, 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I.; Cousins, B. A participatory model of agricultural research and extension: The case of vleis, trees and grazing schemes in the dry south of Zimbabwe. Zambezia 1989, 16, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, P.M. Fertility of dambo soils and the related response of dambo soils to fertilisers and manure. In Dambo farming in Zimbabwe; Owen, R., Verbeek, K., Jackson, J., Steenhuls, T., Eds.; University of Zimbabwe Publications: Harare, Zimbabwe, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.B. ‘Water Used to be Scattered in the Landscape’: Local Understandings of Soil Erosion and Land Use Planning in Southern Zimbabwe. Environ. Hist. 1995, 1, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murisa, T. Arrested Development: An Analysis of Zimbabwe’s Post-Independence Social Policy Regimes. In Beyond the Crisis: Zimbabwe’s Prospects for Transformation; Murisa, T., Chikweche, T., Eds.; Weaver Press: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, P.C. Conservation Agriculture in Eastern and Southern Africa. In Conservation Agriculture: Global Prospects and Challenges; Jat, R.A., Sahrawat, K.L., Kassam, A.H., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Naome, R.; Rajah, D.; Jerie, S. Challenges in Implementing an Integrated Environmental Management Approach in Zimbabwe. J. Emerg.Trends Econ.Manag.Sci. 2012, 3, 408–414. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D. Suffering for Territory: Race, Place, and Power in Zimbabwe; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Command Agriculture and the Politics of Subsidies. Zimbabweland Blog. 25 September 2017. Available online: https://zimbabweland.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 25 September 2017).

- Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade. Country Information Report; Australian Government, April 2016. Available online: https://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/country-information-report-zimbabwe.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2018).

- ZHRC. Statement on Reported food Aid Cases. Presented by Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission at a Press Conference in September 2016. 2016. Available online: http://www.zhrc.org.zw/index.php/ (accessed on 15 July 2017).

- FCO. Zimbabwe-Human Rights Priority Country Status Report: January to June 2016; Updated February 2017; Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ (accessed on 15 July 2017).

- Connell, R.W. The Social Organization of Masculinity. In The Masculinities Reader, 2nd ed.; Stephen, M., Barrett, F.J., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, E. The Management of Protracted Social Conflict: Theory and Cases; Dartmouth: Aldershot, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, K.B.; Pimbert, M.P. Social change and conservation: An overview of issues and concepts. In Social Change and Conservation: Environmental Politics and Impacts of National Parks and Protected Areas; Brüggemann, J., Ghimire, K.B., Pimbert, M.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pimbert, M.P.; Pretty, J.N. Parks, people and professionals: Putting ‘participation’ into protected area management. Soc. Chang. Conserv. 1997, 16, 297–330. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P.S. Ecological Implications of Water Spirit Beliefs in Southern Africa: The Need to Protect Knowledge, Nature, and Resource Rights. USDA For. Serv. Proc. 2003, RMRS-P-27, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gonese, C.; Tuvafurem, R.; Mudzingwa, N. Developing Centres of Excellence on Endogenous Development. In Ancient Roots, New Shoots; Haverkort, B., Ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tarusarira, J. African Religion, Climate Change, and Knowledge Systems. Ecum. Rev. 2017, 69, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, M. The State and Agrarian Change in Zimbabwe’s Communal Areas; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Landscapes, fields and Soils: Understanding the History of Soil Fertility Management in Southern Zimbabwe. J. South. Afr. Stud. 1997, 23, 619–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catholic Commission for Justice, Peace in Zimbabwe, & Legal Resources Foundation (Zimbabwe). Breaking the Silence, Building True Peace: A Report on the Disturbances in Matabeleland and the Midlands, 1980 to 1988; Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, P. Agriculture as a performance. In Farmer First: Farmer Innovation and Agricultural Research; Chambers, R., Pacey, A., Thrupp, L., Eds.; Intermediate Technology: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, G.E. Cultivating Social-Ecological Relationships at the Margins: Agroecology as a Tool for Everyday Peace Formation in Fragile Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, Coventry University, Coventry, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Pascalian Meditations; Stanford University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Primary data source: Dema Farmer Interview-DMA/FI/M/DBV/013. 23 June 2017.

- Primary data source: Dema Elder Interview DMA/ACC/M/019. 28 June 2017.

- Primary data source: Farmer Interview-MHT/FI/M/MC/014. 28 June 2017.

- Primary data source: Traditional Leader Interview-CHK/CS-TL/M/KC. 29 November 2016.

- Primary data source: Headman Interview-CASH/HM/M/SC. 26 October 2016.

- Primary data source: Ward Councillor Interview-SHIN/WC/M/LM. 26 October 2016.

- Primary data source: Farmer Interview-MHT/FI/M/MGT/05. 9 March 2017.

- Primary data source: Agritex Extension Officer Interview-CHK/AEW/M/MS. 12 July 17.

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarusarira, J.; Manyena, B. Reconciliation in Zimbabwe: Building Resilient Communities or Unsafe Conditions? J. Confl. Transform. Secur. 2016, 5, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L.; Light, S.S. Adaptive management and adaptive governance in the everglades ecosystem Farmer interview—MHT/FI/M/MGT/05 (09.03.17). Policy Sci. 2006, 39, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseko, P.; Scoones, I.; Wilson, K. Farmer-based research and extension. ILEIA Newsl. 1988, 4, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- No wealth ranking exercise was undertaken, instead being gauged through observation and interview responses.

- Bayat, A. Life as Politics. How Ordinary People Change the Middle East; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, J. (Ed.) Conflict: Human Needs Theory; Conflict Series; Macmillan: London, UK, 1990; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

| Common Emergent Properties | Examples of Empirical Evidence in Dema Community |

|---|---|

| Resilience | |

| Farming systems, scales and purpose | Livelihood development to ‘instrumentalise peace’: Training hosted at six disparate project gardens; honey production and vegetable processing. |

| Plurality of knowledge applied | Skills transfer as a top-down technical intervention taking place at disparate village gardens. Little known or shared locally of the rich farming traditions of the area. Widespread rejection of traditional beliefs and related farming practices locally. Agritex disengaged. NGO training as ‘knowledge transfer’. |

| Degree of self-reliance | High dependency on state welfare and other external assistance. No attempt at tree planting, ground cover or building strong structures to prevent cyclone damage—assumed to be the responsibility of the state. Felt that wetland management should be addressed through bylaws. |

| Agency | |

| Degree of efficacy | Dema farmers least likely to anticipate or plan responses to stresses and shocks—highly dependent on external services (state and NGOs) for food security and mobilisation for development activities. Unable to envisage a future or plan strategies. |

| Degree of social farming | Lower levels of social farming for exchange of seed or knowledge. ‘Most of the skills they are lost … Some have died, some forget, some are in churches.’ ‘If you collected a lot of people in what you were doing, they don’t believe that you are farming. They believed that you are … agitating.’ |

| Networks coherence | Little coherence, except for honey co-operative linking those engaged from across villages. Wider activities tail off when funding ceases. |

| Peace | |

| Degree of everyday peace | Higher-level threat dynamics in the area—described as political violence, harassment, hatred, discrimination and fear. Leadership concerns identified under peace due to being the perceived source of violence and social division. |

| Degree of social cohesion | Lower levels of social cohesion. Asked why ‘trust’ was not an indicator during FGD: ‘Ah no, that will take time. But it’s slowly changing’. |

| Common Emergent Properties | Examples of Empirical Evidence in Mhototi Community |

|---|---|

| Resilience | |

| Farming systems, scales and purpose | To manage drought and worsening economic hardship: Water harvesting and dams at farm level, expanded to landscape-level drystone walling, tree planting and bio-cultural resource monitoring for protection by volunteer work groups. |

| Plurality of knowledge applied | History of action research with external influences to restore local knowledge and spread innovations farmer-to-farmer. Gradual institutional acceptance and integration with Agritex advice. |

| Degree of self-reliance | Almost all farmers saving seed and producing small grains for drought tolerance. Majority of agroecological farmers managing surface water for irrigation and diversification. |

| Agency | |

| Degree of efficacy | There was a collective will to resist changes that risk pollution or displacement. Leadership concerns identified as issues over which agency could be exerted. Able to envisage a future with planned/listed environmental strategies. ‘Our ambition is to change our region to a region that has water throughout the year.’ |

| Degree of social farming | The highest level of social farming was found here for all farmers, with at least two thirds sharing equipment, resources, labour, knowledge and skills. |

| Networks coherence | A high sense of common endeavour developed through farmer-to-farmer activities. Volunteer network’s activities not dependent on funding. |

| Peace | |

| Degree of everyday peace | Reports of intimidation and exclusion of opposition supporters, involvement of youths in ‘campaigning’, alongside low-level violence associated with criminality. ‘… But when we focus on the land, we can reduce violence, since every farmer would be promoting development. When someone is improving the environment there is peace.’ |

| Degree of social cohesion | Strong social cohesion, particularly amongst AE farmers of different status and political affiliations. ‘I think the introduction of nhimbe has united people, they are always together, laughing together, and sharing stories—to share food. That’s brought us together … it didn’t happen before.’ |

| Common Emergent Properties | Examples of Empirical Evidence in Chikukwa Community |

|---|---|

| Resilience | |

| Farming systems, scales and purpose | To manage soil loss, land degradation and drying springs: Terracing, tree planting, gully and spring reclamation, village gardens and nurseries managed by integrated village committees. |

| Plurality of knowledge applied | History of pioneer agroecological activity, initially from external sources. Knowledge generated from collectively planned actions and restoration of cultural farming and traditions. Participatory farmer-to-farmer learning and experimentation. Development of knowledge ‘like peeling an onion.’ Agritex buy-in. |

| Degree of self-reliance | Two thirds of all farmers saving 4–8 seed types. New varieties introduced to diversify food and trade opportunities. Seed breeding, saving and sharing, and soil and pest management initiatives. |

| Agency | |

| Degree of efficacy | Leadership concerns identified as issues over which agency could be exerted. Able to envisage a future with planned/listed inter-linked environmental and social strategies. |

| Degree of social farming | Farmers were found to be more likely to engage in collective production at the chief’s field. Village gardens instead providing source of knowledge and seed sharing for network members. ‘There is that unity of purpose with the organic farmers, it’s like a community—they come together.’ |

| Networks coherence | Agroecological work united people within and across villages around landscape-level changes and expanded to village conflict management and social support groups. AE village activities not dependent on external funding. |

| Peace | |

| Degree of everyday peace | Exclusion of opposition supporters and involvement of youths in election campaigning. More police harassment reported by AE farmers due to higher engagement in trade. Accounts of shifting world views resulting from inter-linked community peace work: ‘I didn’t know that there is a sense of greed in us that you might not notice—you just think it’s your right. I was such an angry person.’ |

| Degree of social cohesion | High levels of cohesion and embeddedness of AE farmers within leadership reported—more able to resist political pressure. |

| Common Indictors by Research Theme | Case Study Area | ||

|---|---|---|---|

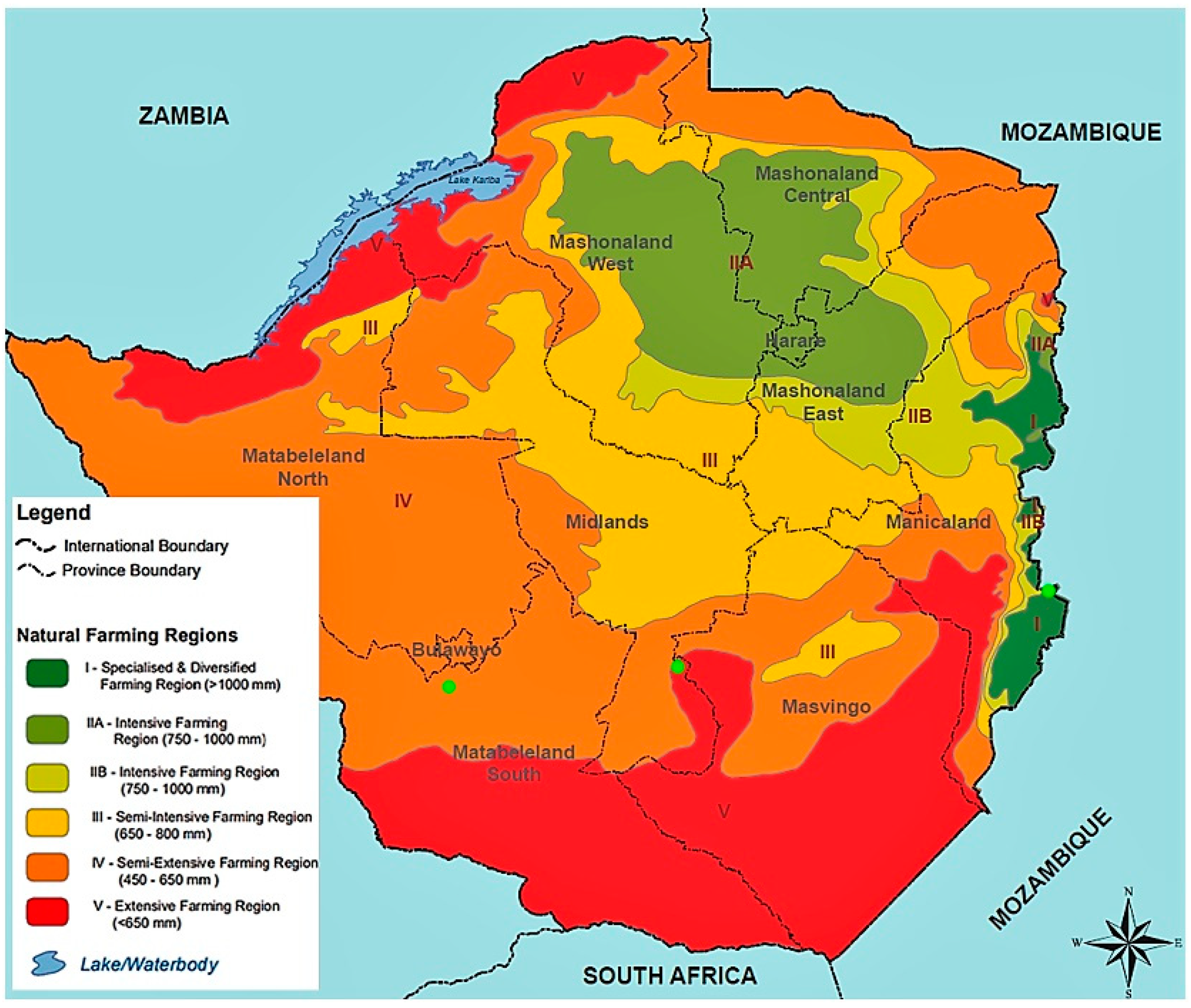

| Dema (NR IV) | Mhototi (NR V) | Chikukwa (NR I) | |

| Resilience | |||

| Productive diversity—crop types and varieties | 100% of CFs / 94% of AE cultivating 2–15. | 80% of CF / 83% AE cultivating 2–15. | 70% of CFs cultivating 6–10 / 61% of AE farmers cultivating 11–25. |

| Seed saving—types and varieties | 69% of AE farmers saving seed. No CF saving seed. | 100% CF saving 4–15 / 98% AE saving 4–20. | 70% CF saving 4–15 / 91% of AE farmers saving 4–20. |

| Small grains—sorghum | 30% of all farmers cultivating small grains | 94% AE farmers / 90% CF. | Small grains not selected due to NR. |

| Experimentation | NPM: 36% CF / 75% AE; organic soil amendments: 81% AE / CF none. | Water harvesting—Infiltration: 20% CFs / 67% AE; diversion drains and dams: 60% AE / CF none; | Organic soil amendments: 10% CF / 96% AE; pests and diseases constant: 40% CF / 13% AE. |

| Agency | |||

| Co-operation and sharing | Ilima: 45% of all farmers; Knowledge: 27% CF / 94%AE; Info: 9% CF / 56% AE; Labour 9% CF / 63% AE. | Nhimbe: 95% of all farmers; Knowledge: 90% CF / 98% AE; Info: 80% CF / 90% AE; Labour: 90% CF / 88% AE. | Participation together in community activities: 20% CF / 57% AE. |

| Unity | As a community: 18% CF / 38% AE; | As a village: CF 40% / 81% AE; | As a community: 57% CF / 86% AE; |

| Decision-making and Influencing | Listened to in household/family: 45% CF / 75% AE; Confidence in village meetings: 36% CF / 69% AE. | Listened to by village heads: 40% CF / 76% AE; Able to make land-use decisions: 60% CR / 60% AE (more women than men). | Able to influence village: 30% CF / 61% AE; Ability to make all planting decisions: 10% CF / 57% (more women than men) |

| Peace | |||

| Good Communication | As a community: 27% CF / 75% AE. Tolerance: different political opinions 36% CF / 69% AE; cultural difference 45% CF / 100% AE. | As a village: 20% CF / 79% AE. (Tolerance or its absence was not raised) | ‘As neighbours’: 70% CF / 91 AE. Tolerance of different beliefs: 65% AE / 60% CF found difference ‘difficult to tolerate’. |

| Trust | ‘Trust’ was an absent indicator. | As a community: 10% CF / 33% AE. | As a community: 30% CF / 57% AE. |

| Coercion / violence | 60% of total felt under threat of political violence: 73% CF / 38% AE. 70% subjected to discrimination on political grounds: 82% CF / 50% AE. | 68% said officials were factionalised (50% CF / 69% AE); Awareness of political violence: 60% CF / 54% AE. | Police harassment: 30% CF / 65% AE; awareness of political coercion: 40% CF / 61% AE; Ability to resist political pressures: 30% CF / 70% AE. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McAllister, G.; Wright, J. Agroecology as a Practice-Based Tool for Peacebuilding in Fragile Environments? Three Stories from Rural Zimbabwe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030790

McAllister G, Wright J. Agroecology as a Practice-Based Tool for Peacebuilding in Fragile Environments? Three Stories from Rural Zimbabwe. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030790

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcAllister, Georgina, and Julia Wright. 2019. "Agroecology as a Practice-Based Tool for Peacebuilding in Fragile Environments? Three Stories from Rural Zimbabwe" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030790

APA StyleMcAllister, G., & Wright, J. (2019). Agroecology as a Practice-Based Tool for Peacebuilding in Fragile Environments? Three Stories from Rural Zimbabwe. Sustainability, 11(3), 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030790