This section identifies, describes and analyses the programmes and financing instruments for sustainable development available in Uruguay in the public sector, the financial sector, NGOs and multilateral credit agencies. For every programme and instrument we propose an alignment with the SDGs they aim to finance in order to understand in which SDGs the financing efforts in the country are concentrated.

7.1. Public Sector

The first of our analyses is of the financing programmes and instruments available to the ministries most directly related to sustainable development—the Ministry of Social Development; the Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mining; and the Ministry of Housing, Territorial Planning and the Environment—and to two relevant government agencies—The National Agency for Development and the National Agency for Research and Innovation.

7.1.1. Ministry of Social Development (MIDES)

This Ministry was created in 2006 under Act No. 17,866 to organise, coordinate, supervise, evaluate and monitor national social policies, in order to consolidate a progressive and redistributive social policy. The Ministry has programmes in the following areas [

25]:

Education: Programmes for young people and adults to reduce illiteracy and dropout rates in formal education and to encourage reinsertion into the education system and completion of the basic cycle of education.

Employment and vocational training: Occupational guidance workshops, social cooperative programmes and economic support for productive projects, with follow-up and training for business proposals taking into account their viability and the socio-economic vulnerability of their members.

Disability: Rehabilitation centres, orthopaedic laboratory, financial assistance for technical aids (wheelchairs, etc.), adapted means of transport, free legal advice.

Homelessness: Programme of assistance for homeless people, offering beds, shower facilities, clothes, dinner and breakfast.

Food security: The Uruguay Social Card is a transfer programme created to provide access to basic food necessities for families in need, enabling them to select the products most suited to their particular situation.

Social Security: The MIDES single-tax system facilitates access to the health system and other Social Security provisions. In addition, the Family Allowances programme enables conditional transfers to encourage children and young people to remain within the education system and to seek regular health checks. The Senior Persons Programme provides financial assistance to people aged 65–70 years who have no regular income and/or live in a critical situation.

Domestic violence: Psychological, social and legal assistance is provided for women at risk of suffering gender violence.

Culture and participation: Programmes to promote the full exercise of citizens’ rights. The support is reciprocated through services to the community.

Identity and documentation: Programme focused on obtaining or regularising national and foreign documents, and promoting the right to identity.

The SDGs associated with the described programmes are summarised in

Table 2. The programmes mainly address SDGs 1, 2, 4 and 10.

7.1.2. Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mining (MIEM)

The MIEM applies the following programmes related to the SDGs [

26]:

IncubaCoOp: To finance new ventures in innovation and knowledge-intensive areas, assisting in the creation of cooperatives in strategic or new-opportunity fields.

Espacio germina (First shoots): To promote and support entrepreneurship by young people (aged 18–29 years), providing training, practical knowledge and tools to facilitate the success of creative initiatives in personal, collective and community development.

C-Entrepreneur: To promote the start-up of companies with potential for growth and job creation, to foster entrepreneurial attitudes in society and to strengthen links and exchanges among entrepreneurs.

Comprehensive Platform in Support of Business Development: To promote entrepreneurship, innovation, the professionalisation of management and the use of technical services. This programme facilitates access to the development services required by micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) to boost their performance and to enable co-financing.

Pro-Certification: To promote competitiveness among MSMEs, providing subsidies to offset the costs of implementation, certification and/or accreditation of technical standards and management improvements.

Handicraft marketing: To promote the sustainability of handicraft producers, fundamentally via their participation in national and international fairs.

Handicraft design, product improvement and competitiveness: To increase the competitiveness of handicraft products.

Handicraft associations: To finance up to 80% of small-scale building or infrastructure projects for the premises of handicrafts associations or groups of workers.

Pro-Design: To support MSMEs wishing to address questions of design in products, textiles/clothing, graphic design, packaging, web/multimedia or interior design.

National training programme: To enhance competitiveness through the professionalisation of business management.

Cutting the electricity bill for electrointensive industries: To enable businesses to maintain or increase production via commercial discounts applied to energy bills.

Biovalue: To transform the waste generated by agroindustrial activities and from small population centres, converting it into energy and/or by-products, in order to develop a sustainable low-emission society.

Public lighting: To provide subsidies for public lighting systems, to promote their modernisation and the implementation of energy-efficiency improvements.

Pro-Bio: To promote the integration of biomass energy generators into the national electricity grid.

Uruguay media (Seriesuy): To promote independent media production, and to sell it at home and abroad.

Sustainable urban mobility (Project Movés): To promote the transition towards inclusive, efficient and low-carbon urban mobility.

Wind energy: To help create favourable conditions for the expansion of wind energy production.

Solar energy: To promote the diversification of energy supply with the incorporation of consumer-producer and renewable sources.

Gender policies in science, technology and innovation: To eliminate educational segregation by areas of knowledge and to strengthen the presence of women in manufacturing, business and employment.

Standardisation and labelling of energy efficiency: To create standards and technical specifications for the classification of energy-consuming products and equipment, according to their degree of efficiency.

Industrial development fund: To grant non-reimbursable funds to companies with investment projects resulting in added value, thus diversifying the national productive structure and enhancing technological capabilities.

Incuba-Electro: A business incubation programme to promote innovative projects in the area of electronics, in the early stages of development.

Gender and energy: To incorporate a gender perspective into energy programmes, projects and policies.

Basic services package: To enable persons in a situation of socio-economic vulnerability to access a package of basic services.

Table 3 summarises the above programmes and relates their contribution to the SDGs., that is mainly concentrated on SDGs 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13.

7.1.3. National Development Agency (ANDE)

The National Development Agency (ANDE) was created by Act 19,472 on 17 January 2017, and is responsible for implementing the

Transforming Uruguay programme for manufacturing reform and competitiveness. This Agency designs and promotes effective, efficient and transparent programmes and instruments, with special emphasis on MSMEs. The following ANDE programmes are related to sustainable development [

27]:

Portal for Entrepreneurs: This website compiles and presents services, support, online resources, news and advice for entrepreneurs in Uruguay.

ANDE Network of Business Start-Up Sponsors: These institutions work together to create and deploy resources to support entrepreneurs in Uruguay.

ANDE Seed Fund: This Fund provides non-reimbursable economic contributions for the start-up or consolidation of projects offering added value, growth potential and job creation.

ANDE Financing Programme: To finance institutions that grant credit directly to SMEs.

Microfinance Development Package: To promote microfinance, through subsidies for the provision of productive microcredits to new clients and the co-financing of training and business-strengthening projects facilitated by microfinance institutions.

Stock Market: Strategies are promoted to enable MSMEs to access the stock market.

Italian Credit: Line of credit provided by the Italian Institute for Cooperation for small and medium-sized Uruguayan or Italo-Uruguayan companies.

Social Entrepreneurship Programme: This financing tool facilitates sustainable business solutions to socioeconomic problems affecting populations with few economic resources and little access to financial services.

National Guarantee System: To facilitate access to financing by promoting, strengthening and publicising guarantee instruments for MSMEs.

Supplier Development Programme: To help develop competitive MSMEs, supporting their participation in national value chains by promoting business opportunities for market leading companies and their suppliers through the development of skills and capabilities in MSME suppliers.

Sectoral Public Goods for Competitiveness: The aim of this programme is to improve competitive conditions within business sectors by developing public goods geared to the generation and provision of information and inputs, thus reducing transaction costs, heightening international involvement and promoting public–private coordination.

Coordination and Competitiveness in Manufacturing: This programme is intended to enhance the competitiveness of companies within productive conglomerates.

Centres for Business Competitiveness: These centres are spaces in which MSMEs and entrepreneurs can access a range of support options to boost their growth and development.

Support for Territorial Competitiveness: An alliance between public, private and knowledge-focused agencies to carry out initiatives in manufacturing, training and human resources, and to strengthen institutional capacities and territorial social capital.

The ANDE financing programmes are summarised in

Table 4. The table shows that ANDE programmes tend to finance SDGs 4, 8, 9 and 17.

7.1.4. National Agency for Research and Innovation

The National Agency for Research and Innovation (ANII) is a government agency established to promote research and the application of new knowledge within productive and social contexts. ANII finances research projects, national and international postgraduate scholarships and programmes to foster innovative culture and entrepreneurship in both the private and the public sectors [

28]. In addition, it helps to coordinate those involved in knowledge development, research and innovation. The ANII programmes that contribute to sustainable development are presented in

Table 5, and they mainly contribute to SDGs 1, 11 and 17.

7.1.5. Ministry of Housing, Urban Planning and the Environment (MVOTMA)

The stated purpose of this ministry, created in 1990 under Act No. 16,112, is to “Design and implement participatory and integrated public policies for housing, the environment, urban planning and water supplies, to promote fairness and sustainable development, thus contributing to improving the quality of life of the inhabitants of the country” [

29].

In its 2015–2019 Five-Year Plan [

29], the National Housing Directorate proposed the implementation of housing programmes that would take into account the heterogeneity of households and facilitate their access to and permanence in appropriate housing. The Plan contains the following main programmes [

29]:

Mutual aid, savings and loans cooperatives and social funds: These well-established institutions foster the social production of housing and urban environments via the self-management of organised groups.

Assisted self-building on public and private land: This form of construction is carried out directly by the end users, complemented with voluntary help from organisations or family groups, and with a technical team provided by the National Housing Directorate.

The construction of housing complexes for retirees and pensioners: These units are intended for the use and enjoyment of beneficiaries of the public pension system whose income is below a pre-established limit.

Construction of housing complexes for the economically-active population: These complexes are created by construction companies, following a process of public tenders, in line with the National Housing Directorate’s priorities for locating new housing within already-consolidated urban areas.

Guarantees for ordinary, subsidised or institutional rent: This nationwide programme facilitates access to temporary housing solutions and provides rent guarantees, for single people and/or families.

The programmes administered by this ministry are all related to access to housing and related to SDGs 1, 3, 10, 11 and 17.

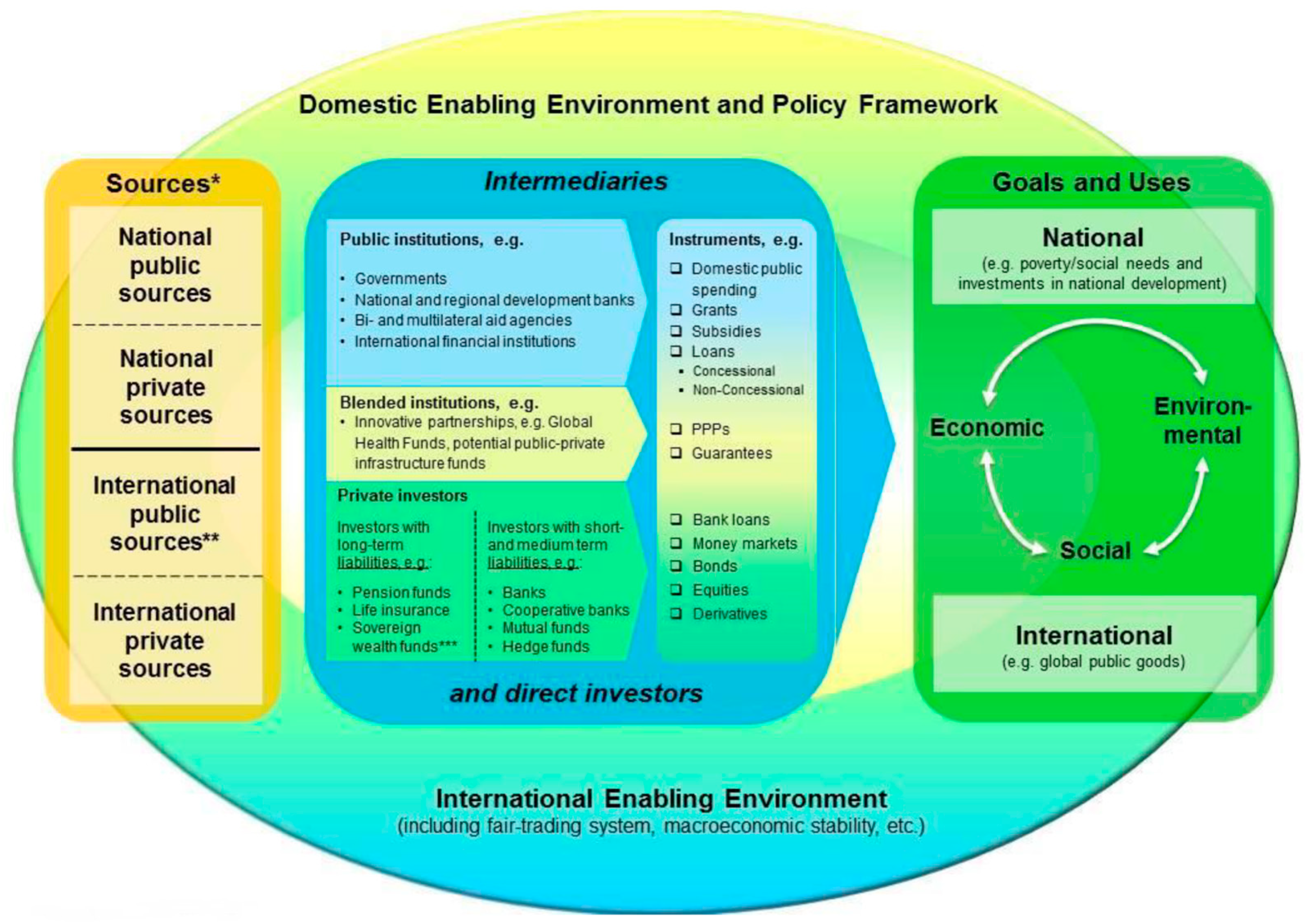

7.3. Financial Sector

The Uruguayan financial system is composed of two public banks, nine private ones and a wide variety of non-banking institutions. The main financial institutions operating in Uruguay are nationally and internationally considered investment grade. This reflects the strength of the Uruguayan financial system, which is composed of a small number of banking institutions, all of which have excellent ratios of solvency and liquidity. One of the characteristics of the banking system in Uruguay is the high degree of participation by public banks. In June 2017, public banking accounted for 43% of the sector, with the private banks composing the remaining 57%. The four largest private banks accounted for 49% of the total business volume of private banking [

32].

In this paper, we analyse the availability of financial instruments, focusing on the sustainable development of a major private bank, Banco Santander, which represents 16% of the Uruguayan financial sector. We also analyse a public bank, Banco de la República Oriental del Uruguay (BROU), which represents 43% of the national financial sector [

32].

7.3.1. Private Financial Sector

Banco Santander provides the following financial instruments related to sustainable development:

Services for university students: The bank provides financial products and services to students, under preferential conditions.

University entrepreneurship: The bank supports initiatives to promote the entrepreneurial culture, and supports technology transfers from the university to the business world, with initiatives related to science and technology parks. The bank’s aim in this respect is to contribute to the sustainable development of society and to human and business progress by enhancing knowledge and innovation.

Supply chain sustainability: The bank applies measures based on ethical, social and environmental criteria, seeking to ensure that sustainability considerations are taken into account throughout the value chain.

Support for SMEs: This programme facilitates the access of SMEs to financial services and credit facilities, to new technologies, to specialised training and to greater internationalisation in new markets.

Financial solutions focused on environmental protection: The bank offers financial solutions and occupies a leading international position in renewable energies, financing projects such as the construction and operation of wind farms, photovoltaic plants, and solar thermal and hydraulic power plants.

Table 8 summarises the Banco Santander financing programmes and their relationship with the SDGs [

33], showing a concentration on SDGs 8, 9, 11 and 17.

7.3.2. Public Financial Sector

The Banco de la República Oriental del Uruguay (BROU) provides the following instruments related to sustainable development [

34].

Benefits for pensioners: Debit card entitling pensioners to a 100% value-added tax refund on their purchases.

Uruguay social card: This card facilitates a monetary transfer to households in situations of extreme socio-economic vulnerability. Its main objective is to assist households that have special difficulty in accessing a basic level of consumption of food and other necessities.

Social tourism loans: This product offers pensioners of all types the opportunity to enjoy a wide variety of holiday destinations and activities within Uruguay.

Microfinance republic: This project promotes the financial inclusion of broad sectors of the population, with specific products for microenterprises and low-income families, sectors that are often ignored in traditional banking.

República Administradora de Fondos de Inversión (República AFISA): This company is legally authorised to act as a trustee for private and public financial trusts. Such trusts may be established to finance commercial, industrial or service activities, real estate projects or the construction of buildings and infrastructure, among other purposes.

The BROU financing programmes and their relationship with the SDGs are summarised in

Table 9. A concentration of the programmes in SDG 10 is evident.