What Should SMEs Consider to Introduce Environmentally Innovative Products to Market?

Abstract

1. Introduction

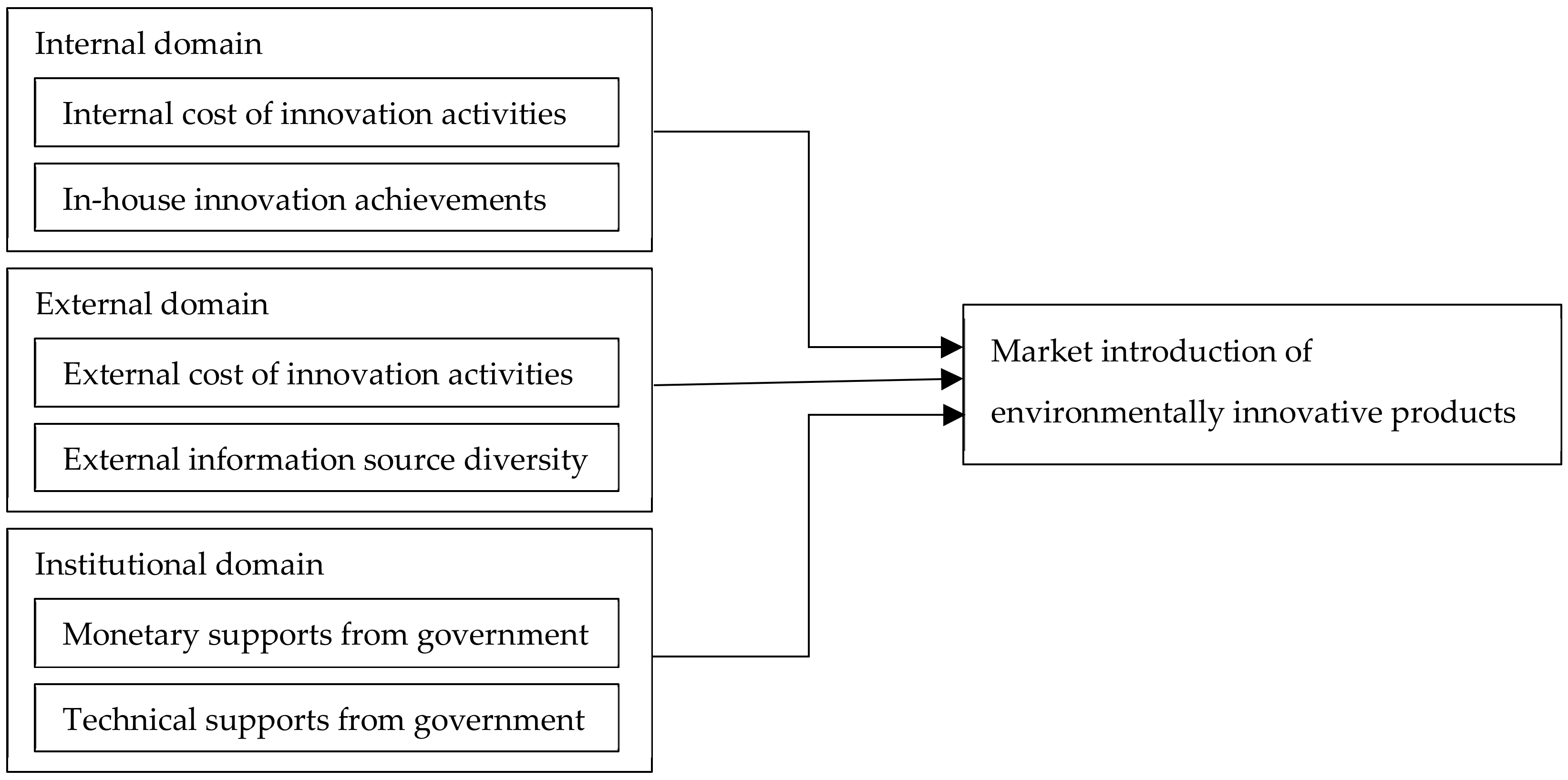

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Internal Domain

2.2. The External Domain

2.3. The Institutional Domain

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Model

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovation. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Bowell, G. A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Chialin, C. Design for the environment: A quality-based model for green product development. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 250–263. [Google Scholar]

- Horbach, J. Determinants of environmental innovation—New evidence from German panel data sources. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Brìo, J.A.; Junquera, B. A review of the literature on environmental innovation management in SMEs: implications for public policies. Technovation 2003, 23, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of The Growth of The Firm; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H.; Chung, Y.; Woo, C.; Chun, D.; Jang, S.S. SME’s appropriability regime for sustainable development—the role of absorptive capacity and inventive capacity. Sustainability 2016, 8, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L. Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Argote, L.; Miron-Spektor, E. Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff, M.; Tsai, W. Social Networks and Organizations; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, R.; Thomas, R.J. Driving Results Through Social Networks: How Top Organizations Leverage Networks for Performance and Growth; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Admin. Sci. Quart. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T. The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Admin. Sci. Quart. 1999, 44, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxenbaum, E.; Jonsson, S. Isomorphism, diffusion and decoupling: Concept evolution and theoretical challenges. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., Sahlin, K., Suddaby, R., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2018; pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Attention to attention. Org. Sci. 2011, 22, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. A Primer on Decision Making: How Decisions Happen; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Org. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Reuer, J.J. Experience spillovers across corporate development activities. Org. Sci. 2010, 21, 1195–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Boston, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Podolny, J.M. Networks as the pipes and prisms of the market. Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 107, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Admin. Sci. Quart. 2003, 48, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Lyles, M.A.; Tsang, E.W. Inter-organizational knowledge transfer: Current themes and future prospects. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, R.; Jansen, J.J.; Lyles, M.A. Inter-and intra-organizational knowledge transfer: a meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and consequences. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 830–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simao, L.; Franco, M. External knowledge sources as antecedents of organizational innovation in firm workplaces: a knowledge-based perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, M.J.; Birkinshaw, J. The role of external involvement in the creation of management innovations. Organ. Stud. 2014, 35, 1287–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, M.J.; Birkinshaw, J. The sources of management innovation: when firms introduce new management practices. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Jennings, P.D. Institutional theory and the natural environment: Research in (and on) the Anthropocene. Org. Env. 2015, 28, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Innovation Survey. Available online: http://www.stepi.re.kr/kis/service/sub02_data_application.do (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Yang, D.; Park, S. Too much is as bad as too little? Sources of the intention-achievement gap in sustainable innovation. Sustainability 2012, 8, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, C.; Chung, Y.; Chun, D.; Han, S.; Lee, D. Impact of green innovation on labor productivity and its determinants: An analysis of the Korean manufacturing industry. Bus. Strat. Env. 2014, 1, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, D.; Chun, Y.; Woo, C.; See, H.; Ko, H. Labor Union Effects on Innovation and Commercialization Productivity: An Integrated Propensity Score Matching and Two-Stage Data Envelopment Analysis. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5120–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Yi, D. Environmental innovation inertia: Analyzing the business circumstances for environmental process and product innovations. Bus. Strat. Env. 2018, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelllacci, F.; Lie, C.M. A taxonomy of green innovators: Empirical evidence from South Korea. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Etzion, D. Research on organizations and the natural environment, 1992-present: A review. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 637–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, P. Effects of “best practices” of environmental management on cost advantage: The role of complementary assets. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 663–680. [Google Scholar]

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A. The ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulanski, G. Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Technology transfer by multinational firms: The resource cost of transferring technological know-how. Econ. J. 1977, 87, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product market introduction | 0.085 | 0.279 | 0 | 1 |

| Age (in year) | 15.089 | 10.686 | 3 | 67 |

| ln (number of employees) | 3.768 | 1.070 | 2.303 | 8.162 |

| ln (annual sales) | 9.020 | 1.537 | 3.296 | 13.903 |

| Listed company (dummy) | 0.066 | 0.249 | 0 | 1 |

| ln (patent applications) | 0.388 | 0.770 | 0 | 5.209 |

| Average product lifespan (in month) | 383.747 | 452.61 | 0.1 | 998 |

| ln (employees for R&D) | 0.164 | 2.108 | −2.303 | 5.823 |

| ln (internal cost for innovations) | 2.572 | 4.415 | −2.303 | 12.084 |

| In-house innovation achievements | 0.909 | 1.193 | 0 | 4 |

| ln (external cost for innovations) | −0.140 | 3.311 | −2.303 | 9.91 |

| Diversity of external information sources | 0.401 | 0.399 | 0 | 0.889 |

| No external information (dummy) | 0.440 | 0.496 | 0 | 1 |

| ln (tax reduction by government) | 0.559 | 1.623 | 0 | 9.543 |

| ln (monetary supports by government) | 1.089 | 2.285 | 0 | 12.161 |

| Use of technological supports by government | 0.989 | 1.981 | 0 | 6 |

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Product market introduction | |||||

| 2. Age (in year) | 0.070 | ||||

| 3. ln (number of employees) | 0.158 | 0.347 | |||

| 4. ln (annual sales) | 0.164 | 0.359 | 0.798 | ||

| 5. Listed company (dummy) | 0.083 | 0.259 | 0.363 | 0.384 | |

| 6. ln (patent applications) | 0.258 | 0.066 | 0.275 | 0.274 | 0.258 |

| 7. Average product lifespan (in month) | −0.123 | −0.041 | −0.114 | −0.092 | −0.049 |

| 8. ln (employees for R&D) | 0.277 | 0.228 | 0.513 | 0.513 | 0.304 |

| 9. ln (internal cost for innovations) | 0.270 | 0.172 | 0.398 | 0.418 | 0.255 |

| 10. In-house innovation achievements | 0.305 | 0.119 | 0.259 | 0.266 | 0.151 |

| 11. ln (external cost for innovations) | 0.263 | 0.129 | 0.336 | 0.332 | 0.226 |

| 12. Diversity of external information sources | 0.285 | 0.150 | 0.359 | 0.373 | 0.197 |

| 13. No external information use (dummy) | −0.252 | −0.136 | −0.331 | −0.355 | −0.186 |

| 14. ln (tax reduction by government) | 0.179 | 0.121 | 0.251 | 0.257 | 0.194 |

| 15. ln (monetary supports by government) | 0.219 | 0.026 | 0.214 | 0.200 | 0.187 |

| 16. Use of technological supports by government | 0.270 | 0.088 | 0.264 | 0.25 | 0.176 |

| Variables (continued) | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

| 7. Average product lifespan (in month) | −0.217 | ||||

| 8. ln (employees for R&D) | 0.502 | −0.341 | |||

| 9. ln (internal cost for innovations) | 0.437 | −0.309 | 0.825 | ||

| 10. In-house innovation achievements | 0.378 | −0.261 | 0.602 | 0.581 | |

| 11. ln (external cost for innovations) | 0.449 | −0.238 | 0.552 | 0.598 | 0.421 |

| 12. Diversity of external information sources | 0.425 | −0.326 | 0.759 | 0.736 | 0.591 |

| 13. No external information use (dummy) | −0.410 | 0.331 | −0.797 | −0.798 | −0.586 |

| 14. ln (tax reduction by government) | 0.322 | −0.140 | 0.371 | 0.353 | 0.250 |

| 15. ln (monetary supports by government) | 0.437 | −0.182 | 0.454 | 0.453 | 0.287 |

| 16. Use of technological supports by government | 0.428 | −0.206 | 0.471 | 0.433 | 0.333 |

| Variables (continued) | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. |

| 12. Diversity of external information sources | 0.543 | ||||

| 13. No external information use (dummy) | −0.522 | −0.890 | |||

| 14. ln (tax reduction by government) | 0.356 | 0.310 | −0.279 | ||

| 15. ln (monetary supports by government) | 0.448 | 0.434 | −0.389 | 0.454 | |

| 16. Use of technological supports by government | 0.484 | 0.481 | −0.406 | 0.443 | 0.609 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | −3.176 ** | −4.193 ** | −4.031 ** | −3.447 ** |

| (0.732) | (0.762) | (0.796) | (0.743) | |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| ln (number of employees) | −0.108 | −0.058 | −0.078 | −0.132 |

| (0.128) | (0.135) | (0.132) | (0.130) | |

| ln (annual sales) | 0.048 | 0.035 | 0.061 | 0.076 |

| (0.090) | (0.095) | (0.092) | (0.092) | |

| Listed company (dummy) | −0.463 | −0.408 | −0.366 | −0.476 |

| (0.235) | (0.239) | (0.234) | (0.236) | |

| ln (patent applications) | 0.358 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.286 ** | 0.269 ** |

| (0.074) | (0.075) | (0.076) | (0.077) | |

| Average product lifespan | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ln (employees for R&D) | 0.595 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.520 ** |

| (0.070) | (0.086) | (0.086) | (0.071) | |

| No external information (dummy) | −0.817 | |||

| (0.513) | ||||

| ln (internal cost for innovations) | 0.139 ** | |||

| (0.031) | ||||

| In-house innovation achievements | 0.413 ** | |||

| (0.058) | ||||

| ln (external cost for innovations) | 0.077 ** | |||

| (0.020) | ||||

| Diversity of external information sources | 1.532 ** | |||

| (0.441) | ||||

| ln (tax reduction by government) | 0.004 | |||

| (0.033) | ||||

| ln (monetary supports by government) | 0.022 | |||

| (0.030) | ||||

| Use of technological supports by government | 0.149 ** | |||

| (0.033) | ||||

| Chi-square | 358.181 | 443.889 | 429.468 | 389.461 |

| pseudo R-square | 0.189 | 0.234 | 0.227 | 0.205 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, D. What Should SMEs Consider to Introduce Environmentally Innovative Products to Market? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041117

Yang D. What Should SMEs Consider to Introduce Environmentally Innovative Products to Market? Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041117

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Daegyu. 2019. "What Should SMEs Consider to Introduce Environmentally Innovative Products to Market?" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041117

APA StyleYang, D. (2019). What Should SMEs Consider to Introduce Environmentally Innovative Products to Market? Sustainability, 11(4), 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041117