1. Introduction

Mostly, literature reviews are presented at the beginning of empirical research and to support a practical development of any solution. In conference or journals papers, the main purpose is to build a context for the further research problem definition. As such, the literature review is to ensure in-depth and comprehensive description of the earlier research works. Therefore, in this paper, it would be necessary to start with the presentation of practical problems as well as the theoretical background of the discussed concepts, for example, multisourcing, outsourcing chain, vertical outsourcing or collaborative networks. In this paper, management science systematic literature review is to focus on evidence-based practices to develop competencies for support of management of relations among outsourcers and outsourcees in supply chains, assuming that sometimes outsourcer can be an outsourcee, as they have a net of subcontractors, who also have their own subcontractors.

The objectives of the paper include:

reviewing and clarifying the terminology describing different forms of outsourcing, offshoring and production fragmentation;

identification of literature sources on relationship management and coordination in outsourcing chain;

showing theories and models of cooperative IT sourcing at the business ecosystem level.

Empirical evidence and academicians’ works suggest that the relationships among companies in the IT outsourcing chains are constantly evolving and nowadays particular business unit does not cooperate with only one outsourcer but with more than one in different constellations, that is, networks, chains. That sentence is the main thesis of this paper. The IT outsourcing literature review is argued to be based on theories of strategic management to emphasize risks and benefits of outsourcing services. Presented hereunder theories explain the IT outsourcing. The main and general research question (RQ) is formulated as follows: How does the management science literature explain cooperative IT outsourcing chains? Some additional questions are proposed, that is,

- RQ1

What is the nature of changeability of supply chains? (ch. 4.2)

- RQ2

What are communication systems and mechanisms in outsourcing chains? (ch. 4.3)

- RQ3

How are business compensation and compliance modelled in outsourcing chain? (ch. 4.4)

- RQ4

What is the nature of contracting services in outsourcing chains? (ch. 4.5)

- RQ5

What is the nature of relationships among stakeholders in outsourcing chains? (ch. 4.6)

- RQ6

What are decision making models applied for outsourcing chain management? (ch. 4.7)

- RQ7

What are governance approaches implemented for outsourcing chain management? (ch. 4.8)

- RQ8

How is integration realized in outsourcing chains? (ch. 4.9)

- RQ9

How is outsourcing chain performance measured? (ch. 4.10)

- RQ10

Is project management approach suitable for outsourcing chain management? (ch. 4.11)

- RQ11

How is strategy management aimed at outsourcing chain enhancement? (ch. 4.12)

Therefore, the structure of the paper is following. At first, different forms of IT sourcing are discussed basing on the last 20 years references. Next, theories of outsourcing are presented taking into account their value for outsourcing stakeholders’ relationship management. Third part covers essential literature review taking into account the research questions RQ1-RQ11. The literature review conclusions inspire to looking for mechanisms to ensure interchain sustainable coordination. Therefore, the proposal of blockchain economy solution is considered. The basic analysis of risks and benefits is presented, followed by a discussion of the findings. Finally, conclusions are drawn, with implications for management practice as well as for further academic research.

2. IT Outsourcing Conceptualization

The first announcement about outsourcing concerned Eastman Kodak in 1988, when they outsourced information systems to IBM, DEC and Businessland [

1] and IBM was announced as the IT service outsourcer. Probably, the idea of hollow corporation was developed earlier but rapid development of distributed information systems and personal computers in 1980s encouraged companies to IT outsourcing. Since that time, IT outsourcing has developed in each business organization in its idiosyncratic way. The hollow corporation is defined as business organization that designs and distributes but it does not produce anything [

2]. It is a firm wherein production of all goods and services is outsourced to suppliers with the only remaining corporate functions of planning, coordination and administration. In this paper, outsourcing is defined as the practice of subcontracting service and manufacturing works to external business units. It is identified as the procurement of services and products from an outside supplier or producer in order to reduce costs, to delegate noncore operations to another business unit, to another country, either by hiring local subcontractors or building a facility in a region, where labour cost is lower [

3]. Oshri et al. [

4] defined outsourcing as contracting with a third service provider for management and completion of a certain amount of work, for a specified length of time, cost and level of service. The third service provider activities are realized in different ways. For example, the centralized shared services are determined by cost reduction that may be achieved when individually provided services are consolidated and when multiple business units within a firm provide similar types of services. In this case synergies may be realized by means of standardization and consolidation. The cost decrease can be achieved by high economies of scale. Plugge et al. [

5] argue that, in this situation, the internal business demands to customize services are often neglected and if internal business departments feel less served, this might affect their perception of the provided performance of the services. Outsourced shared services are realized by an external service provider who will be responsible for the service delivery. Companies make such decisions, because of the absence of firm specific capabilities that are required to provide services. This service delivery way is seen as an alternative for the centralized service delivery mode and in this case an external service provider may provide the centralized outsourced services. The advantage of this approach is that external service results are expected to be more quality-oriented than in-house delivery. The next service delivery mode, that is, the collaborative shared service means that organization provides services to both internal departments and other firms [

5]. According to the proponents of this approach, some capabilities can only be developed over periods of time. So, for example standardization of business processes and quality improvement can be achieved in the long term. This option will not focus on the ultimate form of cost reduction. Cost may be increased as a result of the increase of diversification drive by heterogeneous clients’ needs. As multiple business organizations are involved in this type of agreements, it is important to understand the dependencies in collaborative shared services as boundaries of individual firms may shift. The decentralized shared services delivery approach is perceived as an opposite strategy to the centralized shared services. When a company is characterized as a heterogeneous organization, business units may have different preferences. Firms choose this form of service delivery to meet the idiosyncratic business needs of internal departments and to have a significant degree of flexibility.

For some academicians, for years placing the IT outsourcing in management science was not acceptable. They argued that IT outsourcing can be considered as a business decision model but its consequences belong to finance and economics. For example, strategic outsourcing requires a fundamental decision to reposition the business through a large-scale change programme. There is always a need to specify the reasons for outsourcing, that is, cost reduction, consolidation of data centres, return to core competencies, facilitation of mergers and acquisitions, opportunity to develop start-ups, devolution of organizational structures, usage of IT benchmarking, new IT access, negotiation of a comprehensive software licenses, risk sharing opportunity and global diffusion of knowledge [

1]. However, beyond that there are also some risks and misinterpretations of positive views of outsourcing. For example, there is an illusory confidence that outsourcing vendors work more efficiently than internal teams as well as that outsourcing allows for more flexible contracts and flexibility in keeping good relations. Therefore, there is a suggestion to always compare outsourcing options, to assess the IT providers and their offers, to align IT strategy with business strategy and to accept IT services as commodities.

Taking into account the outsourcing span, the classification of outsourcing options covers total outsourcing, selective outsourcing and business processes outsourcing [

6] but in the aspect of number of vendors there are single vendor cooperation and multisourcing. In a single outsourcer case, one vendor is responsible for the effort and for ensuring that tasks will be executed on time and according to the agreement. Relying on one service provider, the business organization is exposed to the total risk in case of service provider failure. Multisourcing involves breaking up the project into several components that are handled by multiple independent vendors. This option is usually applied in the total outsourcing project. Multisourcing may require much more competitive bids from multiple vendors than from a single provider. Multisourcing, which implies combining IT and business services can be considered and appears to be the long-term dominant trend in global sourcing. In multisourcing, a company considers its business processes as a portfolio of activities. In such cases, production fragmentation can be analysed. It is understood as a division of production processes into separate components that are made by different companies, even located in more than one country. In such production chains, business units are associated with each other by various types of contracts. Therefore, considering vertical outsourcing strategy or outsourcing chain, each company belonging to that chain is assumed to be both an outsourcer for companies located downstream in the production chain and an outsourcee for companies located upstream in the production chain.

The benefits of multisourcing include the increased competition among suppliers in terms of price, quality and degree of innovation, the reduction of operational risk and dependency and the reduction of strategic risk, because of its split between different suppliers. In this paper, multisourcing is considered as a challenge for cooperation between one outsourcee and a set of outsourcers. Special governance is required, which would refer to the processes and the structures that ensure the alignment of strategies and objectives of all the parties involved. For multisourcing, a lot of outsourcing centres are growing up to acquire skilled personnel and to enter new markets. Key emerging markets in South East Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe are becoming interesting in terms of IT industry experience, quality certification and personnel competencies. Hirschheim and Dibbern [

7] have noticed that IT outsourcing has transformed from sole-sourcing and total sourcing arrangements for provision of IT services into complex arrangements involving multiple vendors and many clients. Collaboration between partners is challenging as they have to develop and manage IT services on the same operational level, accepting the same standards, sharing the risks and benefits. Therefore, Social Exchange Theory seems to be suitable to support the understanding of the complexity of collaboration within a multisourcing deal [

8]. The result of such a compromise is an improvement of the operational performance of IT services. The cooperation in outsourcing chain is really a challenge because of the associated risks and uncertainties [

9], which are specified as follows:

uncertainty of cost reduction in the current supply chain via collaboration;

uncertainty of suitable monitoring of performance in achieving the collaborative goals;

uncertainty of alignment of business structures of outsourcing chain partners;

lack of time reduction in outsourcing collaboration;

lack of interoperability of outsourcing nodes’ information systems;

lack of data accessibility, risks of outsourcing chain and IT investment collapse.

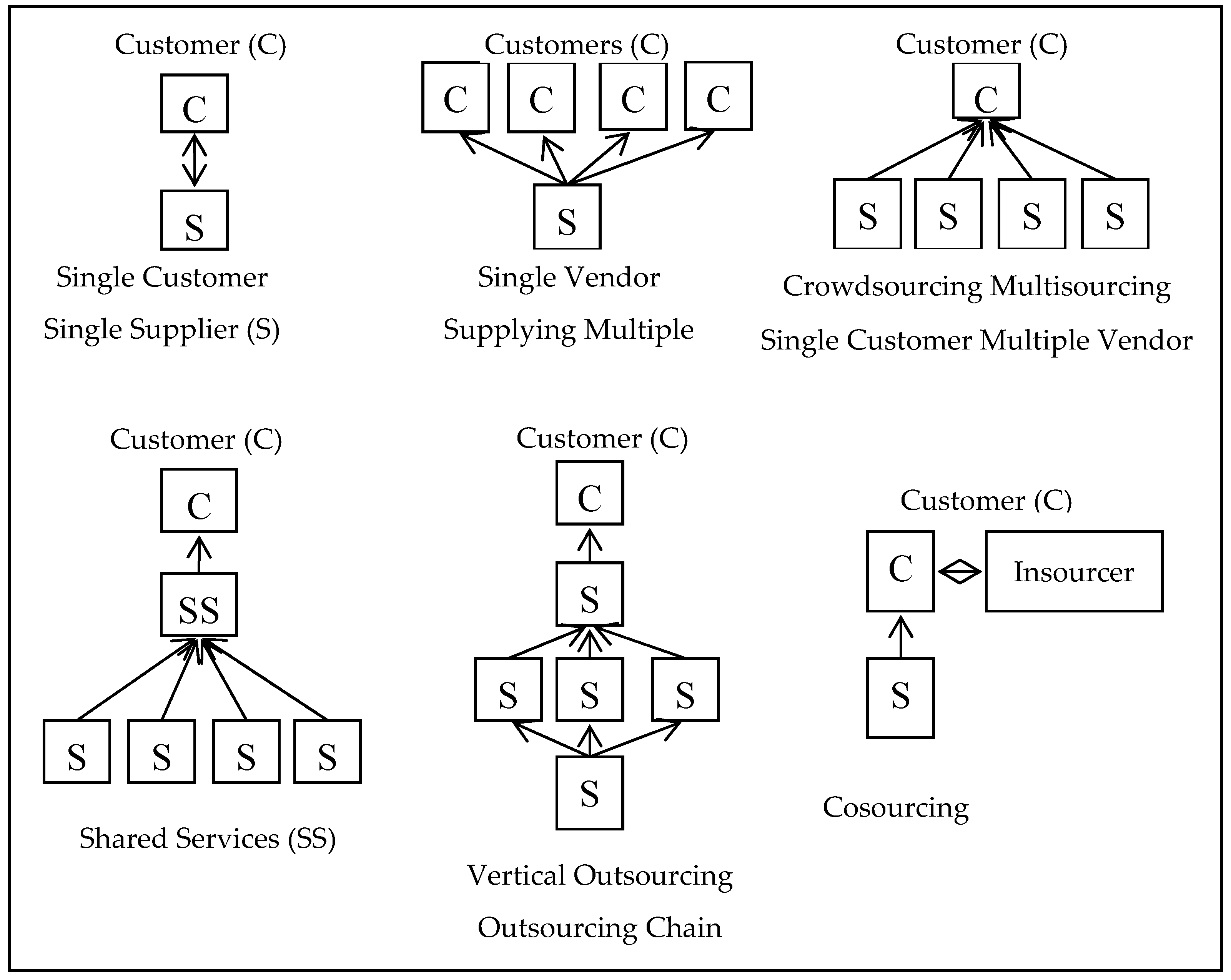

Nowadays, IT outsourcing takes many different forms (

Figure 1). Outsourcing now covers significant partnerships and alliances. It is named co-sourcing, signifying that all stakeholders share risks and rewards and internal employees are insourcers, while external companies take part as outsourcers in these alliances. Collaboration in a sourcing context is accepted as working together and sharing risks to achieve high performance. A shared service centre is the business unit responsible for operational tasks such as accounting, human resources, IT, legal compliance, purchasing, security, transport and logistics [

10]. Co-sourcing as another form of strategic sourcing refers to service that is performed jointly by internal staff and suppliers [

11]. Benefits of this approach include the availability of external staff for project work, access to technical expertise and critical knowledge, which are not available internally within the outsourcee firm. Crowdsourcing is already known as a special mode of multisourcing. Crowdsourcing is recognized as a sociotechnical system providing informational products and services for internal and external customers by harnessing the large communities of people via the Web [

12]. A crowdsourcing process relies fundamentally on free contributions from the crowd and crowdsourcee calls for participation in a particular venture. The group of contributors is usually unrestricted in response to this call. Individuals provide their competences and capabilities to respectively realize the requested tasks. The individuals interested in these tasks may come from different backgrounds, so in general they together ensure a high internal diversity of the crowd. In this way, each crowd is unique as well as the venture supported by the crowd is also idiosyncratic and realized occasionally. Sooner or later such an activity is formalized, so the regular multisourcing is realized or otherwise the crowdsourcing is discontinued. The term “crowdsourcing” was coined by Jeff Howe [

13]. Thanks to the collaborative nature of Web 2.0, crowdsourcing allows a person, an institution or a company to benefit from the work, ideas or wisdom of the Internet people, because each crowd is formed by volunteers. Large scale complex software systems are noticed to be developed through crowdsourcing [

14]. Crowdsourcing practices in the domain of software development are perceived to be aligned with agile methods, service-oriented computing as well as with the traditional waterfall model. Wu et al. [

15] argue that software crowdsourcing has become an emergent paradigm in software ecosystems. They developed a framework including a game-theoretical model for peer reviewed software production in crowdsourcing [

15].

Outsourcing chain is defined as an example of value chain or supply chain. It is an industrialized way of spreading risk rather than leaving risk focused in one place. The risk is shared among outsourcing chain partners and in a similar way trust is dispersed from one to another business partner. According to Glushko, and McGrath [

16] the company’s supply chain is a network of relationships, communication patterns and distribution capabilities to provide raw materials, components, products or services, which are produced by bringing together different business units. The success of a supply chain seems to depend on the integration of business units, which are the chain links and which collaborate. Other important factors cover the competences to establish the long term relationships among partners, the proficiency of flows of products or tasks in the chain, capabilities of information systems, standardization of communication in business processes and workflows and mutual commitment, responsibility and trust [

17]. Baraniecka [

18] emphasized the barriers of a supply chain process integration:

low transparency of the activities in supply chains, which leads to a lack of confidence and commitment;

considerable differences and discrepancies in the companies’ competences;

lack of rational distribution of work;

lack of risk management processes;

lack or inability to evaluate cooperation benefits in the supply chain;

inability to centralize decision making or rather the lack of control of decentralized activities in the value chain.

According to Brown [

19] supply chain perspective is relevant and useful way to develop and manage global software enterprises. The focus on a multivendor software supply chain is a rational way to deliver business software. Outsourcing chain can be used to create competition, drive down costs and improve the quality of delivered systems. So, the business software delivery is characterized as an integrated value chain. While individual separate activities in the supply chain are important, the holistic view of the process suggests considering supply chain integration as a determining factor in management. Brown [

19] has noticed some weaknesses of supply chain implementation. There is a risk of failure to deliver products and services on time, with quality and according to the specification. In traditional outsourcing, negotiation, execution and enforcement of the required tasks were realized in cooperation with one partner but in an outsourcing chain the responsibility is transferred from one to another node in the chain. Therefore, the control of realized tasks is not as easy, even if multiple partnerships rely on mutual trust, respect and open communication. If one node from the chain is going out of business, other organizations must ensure the realization of its tasks. The outsourcee must look for a substitute of that node and quickly insert the lacking link into the chain. Sometimes, partners in an outsourcing chain may have different goals and different needs. They become competitors to one another or just behave opportunistically because of lack of centralized control. Because of the dynamics of market economy, suppliers are often under pressure from many clients to enhance the currently provided services. Requests that are too difficult for them may discourage them from staying in the chain. In a cooperative outsourcing chain there are many opportunities of intellectual property theft. Lack of appropriate contract and regulations and lack of control are risks of outsourcing chain failure. Outsourcing chain business partners may have different motivations and cultures. They are working in different business contexts, so misunderstandings and breaks in communication make the flow of works more difficult. In an IT environment, particularly in the Internet environment, coordination as a service (CaaS) is proposed as a solution just to integrate and coordinate internal and external IT services. According to Van Hillegersberg et al. [

20], CaaS should encapsulate both organizational and technical complexity of service sourcing and integration.

Many business information systems involve business collaboration like supply chains, electronic markets, virtual enterprises and vertical outsourcing (i.e., outsourcing chain). However, the central concept of the multi-party collaboration is still a model of bilateral cooperation. In some cases, chain relationships between multiple stakeholders are broken down into a number of bilateral business transactions but in complex multi-party collaborations, this conversion results in a loss of certain information [

21]. Cross-culture communication is a critical success factor in offshore vertical outsourcing. There are many difficulties in understanding the other partner’s point of view, language, habits, intensions and beliefs. Culture shapes how the problems are understood and approached. Successfully, culture is not taken for granted but it is continuously reconstructed in business communication processes. Multisourcing still requires a set of managerial capabilities to cope with many problems, such as task complexity, task interdependency, workflow integration and knowledge management in multicultural communities. Bapna et al. [

22] argue that in multisourcing a task, interdependency is defined as the degree to which the outputs of different stakeholders affect each other. However, lack of visibility of a vendor’s contribution toward the fulfilment of the interdependent task may be difficult to evaluate. Therefore, this paper aims to present the results of literature review on outsourcing performance implications arising from task interdependency in multisourcing environments. That task interdependency creates certain challenges associated with the measurability of individual outsourcer’s performance. In a multisourcing arrangement, outsourcer and outsourcee need to develop a jointly acceptable set of coordination mechanisms with respect to joint goals. The central control and centralization of decision making for outsourcers’ management seems to be more comfortable for multisourcing optimization. However, decentralization of decision making in an outsourcing chain is more realistic and leads to the necessity of achieving a compromise.

Taking into account an opportunity that outsourcer can be found in another country (i.e., IT offshoring), the additional option of outsourcing has been developed. IT offshoring strategy is aimed at lowering operational cost. However, beyond that offshoring is becoming part of a larger environment of competition. Offshoring organizations are expected to be speedier and more agile due to the large and motivated supply of labour. The typical example of such behaviour concerns young software engineers, who are hungry for success [

23]. They argue that offshoring stimulates the formation of two industry configurations, namely networks and outsourcing chains. Offshoring supports the creation of global networks of software development activities, which are similar to the well-known network structure of the Internet. Each node is connected to many others to create a network of collaborating teams, as it is in the case of an EDA project, which includes the network collaboration between Mexico, Australia, Egypt and Brazil. So, the software development industry resembles a global supply chain of producers and each industry node has to be responsible for adding value as the software is developed and passed in the value chain, according to its software development life cycle. Offshoring can be realized as netsourcing, which is the practice of getting access to centrally managed business applications over the global networks. Particularly, it covers facilities in Internet, named everything as a service (XaaS), which form an alternative delivery channel for business applications and IT services.

3. IT Outsourcing Theories

Theoretical fundamentals of IT outsourcing have been developed and verified by practice for the last 20 years. Kovasznai and Wilcocks [

24] discussed and summarized many theoretical threads having impact on IT outsourcing development. So, IT outsourcing research works are based on theories from the field of economics (e.g., contracting theory, agency theory, transaction cost theory), strategy management (e.g., theory of resource dependency, firm strategy, resource- based theory), sociology (e.g., social exchange theory, institutionalism, theory of social capital, power theory, innovation diffusion and social cognition) or system approach (e.g., general systems theory, system dynamics, modular systems theory).

According to agency theory or principal agency theory, agents are perceived as having distinct and different from the principal’s interests, which they pursue as rational individuals maximizing their benefits. The principal’s (i.e., buyer) task is to anticipate the rational response of agents and to design a set of incentives such as the agents (i.e., outsourcers) find in their own interests to take the best possible set of actions (from the principal’s perspective) [

25]. Agency theory concerns the important issues of designing efficient contractors’ agreements, which are significant because of moral hazard, opportunism and imperfect commitment. Contract is an essential part of outsourcing relations, also because of the lack of full control of agent behaviour and because outsourcers can blame poor performance on circumstances beyond their control. Cognitive dissonance theory is applied to justify the discrepancies between outsourcer’s and outsourcee’s expectations [

26,

27]. Theoretical constructs of transaction cost theory (TCT) concern transaction and production costs [

28]. Transaction costs are determined by the frequency of transactions, asset specificity, opportunism, asymmetry of information (i.e., information impactedness), number of vendors, bounded rationality in decision making, contract negotiation and uncertainty. Uncertainty increases the transaction costs but trust is developed to decrease these costs. According to TCT, the question of external or internal provision of services is decided on the basis of cost comparison. The higher the degree of IT assets’ specificity, the riskier the IT outsourcing and more controllable it should be. In TCT, the dominant risk is derived from information asymmetry between the outsourcee and the outsourcer. There is an inherent inability to monitor the partner’s behaviours and situations, which allow one party to behave opportunistically during the period of the partnership. Tho [

29] argues that risk depends on governance, uncertainty, competitive environment and organizational connections. TCT is valuable for IT outsourcing explanations because the basic sourcing model will be the transaction model, further changed into a relationship model and later into an investment-based strategic model and finally into a strategic alliance. The purpose of a relationship model is to structure partner relationships that are created in business environment and that increase value for both the outsourcer and the outsourcee.

Nash theory of game is a propose of approach to coordinating outsourcers with outsourcees [

30]. Originally it was perceived by Nash as a win-to-loose game but later the principle of value sharing was implemented. Nowadays, it is accepted as a win-to-win game, instead of win-to-loose. So, both outsourcers and outsourcees are able to maximize their benefits in a collaboration. The win-to-win approach highly rewards suppliers for reducing costs. That model is developed for highly collaborative business relationships. In that model, outsourcers are stimulated to make investments to help clients achieve strategic business outcomes.

IT outsourcing is assumed to support the diffusion of innovations. Particularly, it creates opportunities to develop innovations on the market through strategic procurement. By investing in an equity partnership, companies can participate in emerging markets. Diffusion of innovations is beneficial for co-sourcing stakeholders. Companies co-develop and share the cost of innovations and address regulatory requirements that affect them all. IT offshoring is a way to support innovations in the process when the less developed country’s research staff is contracting for on-demand knowledge and innovative software tools and they work in research in highly developed countries.

According to Lacity and Hirschheim [

31] TCT as well as political power models assume that people within companies band together to compete against other companies for resources. Classification of the relationships between the interests, conflicts and power of individuals or political coalitions within the firm is at the core of power theory. According to Dibbern and Heinzl [

32] power is the potential of a party to influence the behaviour of another party. So, in the context of IT outsourcing, the greater the relative power of the IT department within a firm, the more likely is that co-sourced IT services will be duly substantiated and properly controlled.

Beyond that, IT outsourcing is strongly based on organizational resource theories which are further differentiated as follows [

33,

34]:

resource-based theory of the firm, including identification of inherent characteristics of business processes;

resource-dependence theory, covering relational characteristics of IT outsourcing relationships;

knowledge-based view of the firm, focusing on the identification of business analysis and software artefacts;

theory of core competences, according to which all IT services that are peripheral for the firm should be outsourced;

contractual theory arguing that only IT services for which the same contractual behaviour for vendor and buyer can be ensured, should be outsourced;

social exchange theory emphasizing that only outsourced can be the IT services where each stakeholder can follow their own self-interest, when transacting with the other self-interested stakeholder;

stakeholder theory arguing that in IT outsourcing a balance can be achieved between stakeholders, who are business managers, IT managers, end users at the client side as well as customer account managers and key service providers at the vendor side.

Gottschalk [

33] argues that according to the resource-based theory, performance differences across companies can be attributed to the variance in the firms’ resources and capabilities. Idiosyncratic resources that are valuable, unique and difficult to imitate can provide the basis for competitive advantages and positive returns. Such resources are usually managed internally as critical for business strategy realization and never outsourced. While resource-based theory focuses on the company’s resources, activity-based theory perceives the business as a bundle of activities critical for business strategy realization. These activities are ordered in a value chain or network. Porter’s value chain model covering primary and secondary business functions specification is considered helpful in making decision on which functions should be outsourced [

35]. Similar to Porter’s model the cloud value chain reference model was developed by Mohammed et al. [

36]. The model breaks IT services down into three main virtual layers. Links between layers or interdependent services can take horizontal, vertical and diagonal paths. Basing on the Porter value chain model the following activities are specified in the cloud value chain model:

primary services layer covering core infrastructure services;

cloud-oriented support service layer including all activities developed to support and enable the cloud in real world business ecosystems;

business-oriented support service layer covering all nontechnical business services.

The company’s top management question is which of the cloud computing value chain services should be outsourced and which stay insourced. The value chain concept has a significant impact on outsourcing relationship development as well as an integration of outsourcing partners in vertical chains. Perhaps, customized business application and web portals for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) do not have complex life cycle but the enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems are provided by software dealers and many different stakeholders, who are involved in the development and implementation processes. Frutiger et al. [

37] proposed a solution named Open Platform Outsourcing Ecosystem, which members are outsourcing value chain links. Authors argue that whereas the concept of supply chain focuses on efficient transfer of materials to manufacturer, the software development value chain emphasizes considering linked firms in terms of the value they add to the final software product. Integration is needed to ensure that the components work together.

4. Literature Survey on IT Outsourcing Chain

Systematic literature review (SLR) is a research method used to aggregate evidence from repositories of publications. It concerns clearly formulated questions and uses systematic and explicit criteria to identify publications, select publications relevant to the prespecified questions, analyse the data included in the relevant publications abstracts and full texts. The SLR method is to bring the high level of rigor to reviewing research evidence. The applied procedure was based on recommendations presented in References [

38,

39]. Systematic literature review is assumed to be a formal iterative approach for analysis of the past experience to prepare the future decisions. It requires locating, selecting, exploring and reporting. It provides a means for practitioners to use the evidence provided by previous research to inform their decisions. For theoretical background, a systematic literature review can be conducted in the areas of Information Systems, system management, chain management, distributed systems studies, relevant to the problem of coordination and evaluation of distributed systems’ coordination. An overall search is carried out on Web of Science, Science Direct, AISeLibrary, Scopus, Sage Journals, Google Scholar and IEEE Xplore databases, considering the period from 2009 to 2019. In this research, the top journals on information systems (i.e., Information Systems Research, MIS Quarterly, Journal of Association of Information Systems, Journal Management Information Systems, Journal Strategic Information Systems, European Journal of Information Systems and Information Systems Journal) were reviewed. The research field covered three overlapping topics (

Figure 2).

Preliminary search query was done using combinations of AND and OR between the terms in each row:

primary terms: searched in metadata: IT outsourcing, sourcing, vertical outsourcing, outsourcing chain, IT outsourcing blockchain, multi-sourcing

secondary terms: searched in topic, title, abstract and keywords, depending of data source: supply chain, relation changeability, communication, compensation and compliances in outsourcing, contracting, stakeholder, decision making, governance, integration, performance measurement, project management in outsourcing and strategic considerations of outsourcing,

tertiary terms: searched in topic and in title/abstract/keywords: vertical software development, vertical integration, vertical cooperation, distributed systems

conceptual terms: model, theory, survey, case study, field study, review.

Taking into account the presented above theories, the paper aims to answer questions on IT outsourcing chain management, on institutional mechanisms that support business partner relationship development, on creating value and avoiding failures. In an IT outsourcing chain, it is crucial to communicate with all the involved stakeholders. Omitting at least one of them can result in an outsourcing failures. Beyond comprehensive communication, the win-to-win strategy and change management are critical. There is a significant need of visibility over the data, that is, who is spending what and who is working with or for whom. This transparency seems to be important in the aspect of controlling the outsourcing chain. That lack of transparency prevents chain optimization. Outsourcers and outsourcees are less willing to cooperate with business partners who do not have purchasing contracts, nor the policies and procedures. The risk of being dependent on a single provider can be mitigated by assuming in contract the cooperation with strictly one vendor. Multiple providers cooperation can make outsourcing more difficult. Tyrvainen [

40] has done some research on vertical software industry development, according to which, vertical software industry covers primary and secondary software producing organizations. Numerous vendors may cooperate vertically as well as horizontally in multiple network constellations, which ensure a large market for them. The main research method consists of the following steps:

The key sources identification. The preliminary literature reviews are done using Thomson Reuters Web of Science (WoS) as the primary search tool. Then the main results are identified for discussion, so further queries to the most significant journals are formulated;

The content analysis was supplemented by the Scopus literature search engine. The fundamental reviews are done using the following tools: AIS (Association of Information Systems) eLibrary, Google Scholar, IEEEXplore Digital Library, Sage journals, ScienceDirect.com and Scopus;

After deduplication, the results are supplemented by literature analysis focusing on IT outsourcing management. Eventually, some web sites are added to ensure sufficient background on the specific research in IT outsourcing domain;

The literature sources and definitions of popular topics allow to identify the review questions. Many items refer to the IT outsourcing, sourcing, offshoring, multisourcing, resource-based theory, activity-based theory, TCT, outsourcing chain, outsourcing blockchain and strategic alliance. The selection of search items requires significant analysis;

In-depth searches relying on content analysis and citations to capture a full picture of the discussion on the IT outsourcing chain and on its relationship management mechanisms;

Validation of the completeness of the literature set;

Structuring the knowledge reviewing results;

Presentation of key findings and implications for practice;

Concluding and final evaluation of presented approaches.

As mentioned above, relationship management in IT outsourcing chain is an important issue, because it is to ensure consistency in terms of outsourcing objectives and business objectives. Relationship management is developed to ensure coordination of activities of outsourcers and outsourcees, ensure adherence to standardized outsourcing methods and processes, to avoid redundancies in activities and to manage risks and quality [

6]. The outsourcing chain relationship management can have an impact on social capital development through strengthening cultural understanding by visiting the supplier and other stakeholders and by classification of goals and communication. For each reviewed publication the following characteristics were defined to answer the question of which mechanisms support the IT outsourcing chain in a business group: authors, title, source, year of publication, research questions, theories underlying the realized research, research tools and methodologies, study design and findings. The publications’ analysis has covered the last 10 years. The identified research methods were as follows:

stakeholder opinions’ survey;

research articles including data collection via questionnaires;

literature survey to identify critical issues in outsourcing chain management;

focus group discussions exploring a specific set of issues;

case study covering analysis of a single site or a few sites over a certain period of time.

The case studies usually involved in-depth analysis and description of a phenomenon and they were realized according to Yin [

41]. In general, this paper presents the state of the art research papers in management science.

Table 1 covers searching results for “IT outsourcing chain” phrase.

The numbers of publications in

Table 1 are rather incomparable. Google Scholar includes thousands of publications but some important publications are included in IEEEXplore. Therefore, in

Figure 3, the growth rate values are visualised on a linear chart to show the increase and decrease in the number of publications over time and according to the mentioned above particular sources. Assuming that the volume of publications in year “t” is V

t, the growth rate is V

t/V

t-1. Although SAGE journals and Google Scholar included thousands of papers on IT outsourcing chain, the growth rates presented in

Figure 3 revealed that AIS eLibrary, ScienceDirect.com, Google Scholar, Scopus and SAGE journals published yearly similar numbers of papers on IT outsourcing chain unlike WoS and IEEEXplore. Next, 146 publications were chosen as suitable for further considerations. The papers covering other outsourcing issues were excluded as not suitable.

4.1. Introduction to Results’ Analysis

The content of the selected papers was reviewed and although the criterion was set, the analysed articles emphasized a lot of other issues connected with that keyword. The reviewed papers analysis was carried out by reading the articles and finding references to specific constructs, which were as follows:

flexibility, agility and dynamics of relationships in IT outsourcing chain;

communication in IT outsourcing chains, as well as in the supply chain and in the value chain and information sharing among business units;

compensation scheme and guardian model in IT outsourcing chain and their value for partner relationship management;

compliance management, application of contingency theory as well as conflict resolutions methods to ensure internal consistency among business partners in outsourcing chains;

contracting and contract management as a premise of relationship development and management;

culture’s and social issues’ impact on business partners relationship management in outsourcing chains;

decision making methods, algorithms for outsourcing relationship modelling and inter-team coordination support;

application of game theory and event driven flow models as well as multiagent systems and distributed artificial intelligence for outsourcing chain management;

IT outsourcing governance problems and challenges, economic issues, that is, cost, buyback, revenue and service quality economic impact;

integration of business partners, services and information in outsourcing chains, usage of staff experience, blockchain economy and knowledge management to support outsourcing processes integration;

multisourcing maturity modelling and its value for business partners’ relationships’ management;

business partners’ activities specification in IT outsourcing chains and measurement of operational performance;

project management in IT outsourcing chains and focusing on specific issues in project management, that is, subcontracting and procurement;

risk management, disaster recovery, security and business continuity planning as multidisciplinary approaches developed to support IT outsourcing chain management;

outsourcing chain stakeholders’ identification, their roles and responsibilities, crowd as a specific stakeholder and advantages of stakeholder management;

business strategy management for IT outsourcing chain development and the value of strategic alliances.

After the analysis, all 146 papers were grouped into 11 categories. Not all the analysed papers are representative enough for the categories presented below in the subchapters, therefore only the most valuable 75 papers were included in the

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12. The sections below summarize different research approaches towards the specified above concepts.

4.2. Changeability of Business Partners’ Relationship in Outsourcing Chains

The content analysis reveals the dynamics of outsourcing relationships. Monitoring of the evolution is done by identifying of the roles played by different service providers as well as by recognizing of the task-knowledge coordination, process alignment, cloud computing implementation and lean management. Flexibility and agility are accepted as strategic imperatives and they have implications for the future research and managerial practice (

Table 2).

4.3. Communication in Outsourcing Chains

Information sharing is considered as a significant component of cooperation in supply chain management. However, there are problems of information dissemination in outsourcing chains, because of the disaggregation, misinterpretation and incompleteness of information. Information sharing considerations are included in transaction cost theory (TCT), contingency theory, resource-based view, resource dependency theory and social exchange theory. Taking into account presented in

Table 3 papers, supply chain communication systems determine chain business success. Quality of information (QoI) is currently evaluated for networks and is increased by modern technology implementation.

4.4. Compensation and Compliances in Outsourcing Chains

Compensation and compliance are essentially based on the firm interdependence theory. Compensation schemes are assumed to lead to desirable outcomes in multi-sourcing, however, the problem can be met also in outsourcing chain, where a high task interdependence can arrive. Agreements and controlling the tasks are proposed as solutions to manage the compensation schemes, however, Bapna et al. [

22] proposed the implementation of the guardian model for controlling the multi-sourcing arrangements (

Table 4). In outsourcing chains, business partners’ requirements’ compliance can be supported by the implementation of several contingency variables, for example, power, dependency, distance, knowledge resources. However, collaboration in outsourcing chains may induce bilateral or even multilateral conflicts. Lacity and Willcocks [

54] answer the research question on types of interorganizational conflicts in outsourcing relationships.

4.5. Contracting as a Premise of Outsourcing Relationships’ Development

Vertical outsourcing and multi-sourcing are growing and IT services are provided by multiple suppliers but not all organizations are getting planned benefits and service quality within multi-supplier environment.

There is still need to systematically realize research on how to negotiate contracts and how to develop contract-based relationships. Although there are practices. that is, Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL), Service Level Agreements (SLA) management, Enterprise Service Management and Responsible, Accountable, Consulted and Informed (RACI) matrix, the question is still open and significant proposals are included in

Table 5.

4.6. Stakeholder Problems and Challenges in Outsourcing Chains

IT outsourcing practice and research mainly consider the outsourcing phenomena as a generic fulfilment of the required functions by external parties. However, the relationships involve interorganizational business units in interorganizational arrangements named service chains or networks, which consist of multiple specialist parties that collaborate to deliver services. In each outsourcing chain case, the stakeholder teams are different but some generalization on their characteristics and behaviours can be formulated (

Table 6).

4.7. Decision making Models and Outsourcing Relationship Modeling

Global economy and increase of customer expectations in terms of costs and services have an impact on effective reengineering of outsourcing chains. For customers, it is important to perform cost-benefit analysis of outsourcing alternatives before making a final decision on an outsource or insourcee. Therefore, different pragmatic approaches have been developed for option analysis, simulation and optimization. The formal and semiformal models are supplemented by their practical verification and application of proposed algorithms. Included in

Table 7 papers focus on multi partner collaboration modelling. However, decision models based on game theory are still popular. The software agent technology and particularly multiagent system are implemented to support outsourcing cooperation, negotiation and exchange of transactional information.

4.8. Outsourcing Chain Governance Problems

As the outsourcing of key IT services and business processes becomes popular, the effective management of the outsourced business functions and prediction of suppliers in the chain are important. Governance issues concern cost-benefits planning and control. Particularly the coordination and transaction costs are significant subject as they are emphasized in coordination theory, transaction cost economics and incomplete contracts theory (

Table 8).

4.9. Integration Links in Outsourcing Chains

IT outsourcing is posited to unfold complex relationships among business units, that is, outsourcers and outsourcees. The complex service environments of outsourcing settings entail significant challenges for customers. They are struggling with management of various providers and integration of interdependent services. The outsourcing chain internal integration issues are discussed in papers included in

Table 9.

4.10. Performance Measurement for Outsourcing Chain Management

Firms outsource the development and acquisition of information systems needed to improve business processes. Managers working on outsourcing decisions often struggle to understand and balance the external Information Technology impact on existing business processes, as well as on individual stakeholders, for example, end users in an outsourcing chain and on business strategies of the firms involved. Therefore, research work is needed on methods of evaluating the performance capabilities of information systems prior to their full implementation as well as during their exploitation. Different measures and methods to cope with performance evaluation are presented in papers in

Table 10.

4.11. Project Management Approach for Outsourcing Chain Management

The gathered experiences on IT outsourcing case studies ensure some recommendations on structuring the outsourcing relationships. However, the growing trends in IT globalization and outsourcing provide opportunities to attack the supply chains of critical information systems to get valuable business information. IT outsourcing chain partners are mutually dependent and that dependency has been increasing in recent years due to outsourcing globalization and rapid innovation in IT. The increase of dependency brings some risks and uncertainty. There is also a need to identify coordination mechanisms, which could help address the uncertainty. Taking into account dimensions, such as risk, uncertainty, cooperation, relationship structure and business opportunities, the suitable references can be analysed. As it is presented in

Table 11 the project management approach and mentioned above project dimensions are discussed in literature on outsourcing chains.

4.12. Strategy Considerations in Outsourcing Chain Management

The relations of business strategy and evolution of firm structure are investigated in some papers following Chandler’s opinion that structure follows structure. Nowadays, discussion focuses on the alignment of business and information technology. These problems concern not only individual companies but also the whole supply chains, networks and vertical outsourcing chains. Business organizations outsource their information technology related services to third party vendors for quite a long time, so there is a necessity to analyse that vendor’s business strategy.

Table 12 summarizes the discussion on strategy management issues in the context of outsourcing and supply chain management.

5. Blockchain Economy for IT Outsourcing Chain Management

The realized review of literature inspired further search for a mechanism suitable for IT outsourcing interchain coordination. This paper is asked what type of regulation can be suitable to further stimulate internal sustainability. Having looked at available regulatory tools, the shifting regulatory perspectives, possible side-effects, outsourcing services interoperability, standardization and self-regulation, the general feeling is that a fresh approach is required. Taking into account the speed of technological change, more flexibility is needed in sourcing chain management. The imposition of renewed and directed regulatory instruments make sense. That does not mean that more regulation is required. In this paper, a sourcing chain is considered as embedded in business relationships rather than purely as chains of strictly economic transactions. Attention should be drawn to the role of institutional norms and technical standards, beyond the narrow economic sphere. In determining how sourcing chains are governed, there are some crucial variables:

high volume and complexity of transactions;

ability to codify routine transactions;

capabilities in transaction variability development, because suppliers are able to meet buyers’ requirements.

Strategic outsourcing requires nonroutine and nonrecurring tasks but operation, process or product outsourcing covers routine and programmable tasks. However, for both types, control is required and defined as a set of mechanisms that is used to motivate outsourcers to achieve desired project goals. Formal control mechanisms comprise contracting and management techniques that are experienced by a controller over a controlee in a sourcing chain. Contract as an agreement between two or more parties involves negotiations and finally stabilizes relations among stakeholders in outsourcing chain. Contract elements are presented in ArchiMate language (

Figure 4). They are basic business units of analysis, because they are the source from which actions originate. For the strategic and operational outsourcing, important analytical steps are the identification of the important business partners and their perceptions on important topics such as the nature of the problem, the desired solutions and their views on other stakeholders. Therefore, it is important to get the picture of each partner and the dependency relations, which result from the distribution of resources, power, benefits and risks between the partners. As it was noticed by Huxham and Beech [

115] power has been of particular interest in research on supply chain relationships. There are asymmetry of information and imbalance or inequality of power in all interorganizational relations. O. Williamson adds lack of trust and opportunism as the threats of achieving synergy in outsourcing collaboration.

Managers, who conduct outsourcing contracts, include basic control and service execution provisions to ensure continuity of service at the appropriate levels, profitability and value adding to sustain the commercial viability of all involved parties. The outsourcing governance process should provide the mechanism to balance risk, service demand and provision as well as to increase mutual trust and reliability. Implementation of outsourcing contract ensures focus on the transformation journey across the whole business organizations. It requires designing business processes, information, data and software applications to support outsourcing chain management and control. Basic processes for controlling cooperation among outsourcers and processes in outsourcing chain management are presented in ArchiMate language and included in

Figure 5.

The processes concern management of services provided by all types of vendors (i.e., outsourcers) to meet enterprise (i.e., outsourcee) requirements. That includes the search and selection of suppliers, management of relationships, management of contract and reviewing and monitoring outsourcer performance and supplier ecosystem (including upstream supply chain) for effectiveness and compliance. Particularly important seems to be risk management, what covers identification and dealing with risks relating to vendors ability to continually provide secure, efficient and effective service delivery. Therefore, in this paper, blockchain economy solution is proposed to cope with difficulties of IT outsourcing chain management. The blockchain economy concern business rules that are coded in by one of the parties by consensus from all stakeholders. The blockchain software executes coded business rules whenever the new transaction matches certain conditions. Originally, blockchain is the formal name of the tracking database underlying the digital currency bitcoin but now the term is used broadly to refer to any distributed electronic ledger that uses software algorithms to record transactions with reliability and anonymity [

116]. The blockchain system is a self-sustaining, peer-to-peer database software for managing and monitoring transactions [

117]. The system is to protect the network of stakeholders against domination of the network by any single node. Network or chain participants stay anonymous. They are identified by pseudonyms. Each transaction in outsourcing chain is processed just once, in one shared electronic ledger. Outsourcing chain partners use the distributed, verified by all of them and nearly real-time ledger of transactions for records verification. This central but distributed ledger of transactions allows auditors and controllers to monitor the flow of financial data and makes all transactions visible to other partners in outsourcing chain. The blockchain technology enables verification of outsourcing chain partners’ documents such as certificates, licenses, proofs of records, transactions, processes and events. The technology supports monitoring of movement of assets such as transferring money from one node to another in outsourcing chain, their asset ownership registration and management of business partner identities [

118]. The blockchain economy is based on three solutions, that is, encryption, mutual consensus verification and smart contracts. The blockchain is an incremental list of records named blocks that are linked together and secured using cryptography. The blocks are forming a chain, which copies are stored across several peers on a network, so they all can see the chain and its contents. To add a new block, a node must find a key to a random pattern generated using cryptography and verify the block itself. Adding a new block is broadcasted to all the other peers on the network, so they can update their copies of the blockchain [

119]. Each block is linked to the previous one after validation and consensus of all participants. IT outsourcers, that provide complex support, need well-defined Service Level Agreements (SLAs) to set up clear expectations and to ensure quality of service and legal protection. So far, SLAs usually were applied for mutual benefits in bilateral collaboration. Smart contract is computer software that helps companies deal with complex outsourcing situations in multi-partner chain. Some smart contracts can be very simple, like putting a timestamp on a transaction while some are more complex and require the formal agreements of parties beforehand.

The blockchain technology gives rise to a new type of economic system. However, as it is in the case of new technology, its acceptance is risky, although the technology creates the opportunity to reduce opportunism, information asymmetry, insecurity and ambiguity of transactions by providing transactional disclosure. In the blockchain economy, the outsourcing partner must accept the rules and software available for all of them. The outsourcee must have the blockchain software to control the community of outsourcers. The authority and power belong to outsourcee, who is able to invite and remove outsourcers from the chain, however, under the super-visioning of other nodes in the blockchain. This technology implementation is questionable in case, when outsourcing partners do not accept the transparency of their relationships with other partners. Blockchain technology can be applied in distributed systems for cryptographically capturing and storing a consistent and linear event log of transactions between networked actors. Therefore, it is applicable for operation and process outsourcing but for strategic outsourcing based on nonroutine approaches the traditional contracts are constantly suitable. There are some other questions, for instance on how blockchain applications can replace intermediary service providers, what in situation when an important outsourcer does not accept the technology and rejects consensus agreement or how implement blockchain system to complement current traditional outsourcing collaboration. The negotiation of smart contracts may be associated with substantial coordination costs to mitigate outsourcing risk.

6. Conclusions

Taking into account the literature survey, an evolution of considerations on IT outsourcing development and management should be noticed. Although the basic theoretical background, that is, transaction cost theory, agency theory, game theory, incomplete contracts theory, stakeholder theory, resource dependency views, activity based theory, has dominated for years almost without change, the new viewpoint are arriving, particularly because of IT innovativeness. For years, the basic issues were formulation and management of bilateral agreements and alliances. Currently however, chain management and vertical outsourcing problems arrived. These problems appeared simultaneously with the beginning of multi-sourcing and offshoring and particularly with virtual organizations, cloud computing and Internet economics development. Probably in the future, a lot of research works will be done because of the necessity to develop new business models for outsourcing chain management. Literature survey allowed to notice that outsourcing chains’ management is combined with many other issues, that is, dynamics and agility, communication, compensation and compliance, contracting, stakeholders, decision making models, governance, integration, performance measurement, project management and business strategy development. In the literature survey, 146 papers were reviewed, which were published in 2009–2019 years. 50% of that papers were accepted as significant for IT outsourcing chain studying and the research findings are presented in tables. Papers on stakeholders’ relationships and behaviours, on governance of chains and on performance measurement are considered as the most valuable for outsourcing chain management. Only one paper concerns strictly vertical outsourcing management. Therefore, there is an opportunity and need to fill the gap and in future work focus on vertical outsourcing management modelling. Since 2015, the blockchain technology has been developed to support financial transaction controlling as well as supply chain management. IT outsourcing chain is slightly different, however, also here for operation and process outsourcing that technology is very promising to support internal balance and sustainability of outsourcing chains.