A Critical Consideration of Environmental Literacy: Concepts, Contexts, and Competencies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Development of Environmental Literacy

1.2. Purpose of the Research

1.3. Importance of Institutions, Social Groups, and Individuals

1.4. The Importance of Science Curricula and Textbooks for Understanding Systems Related to the Environment

1.5. The Impact of Teaching Methods and Extra-Curricular Activities on Achievement

1.6. Research Questions

- Q1: How do experts define environmental literacy?

- Q2: Which concepts and contexts are included in the framework of environmental literacy?

- Q3: What are the competencies of the environmentally-literate individual?

- Q4: What should be done to promote the development of environmentally literate individuals?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

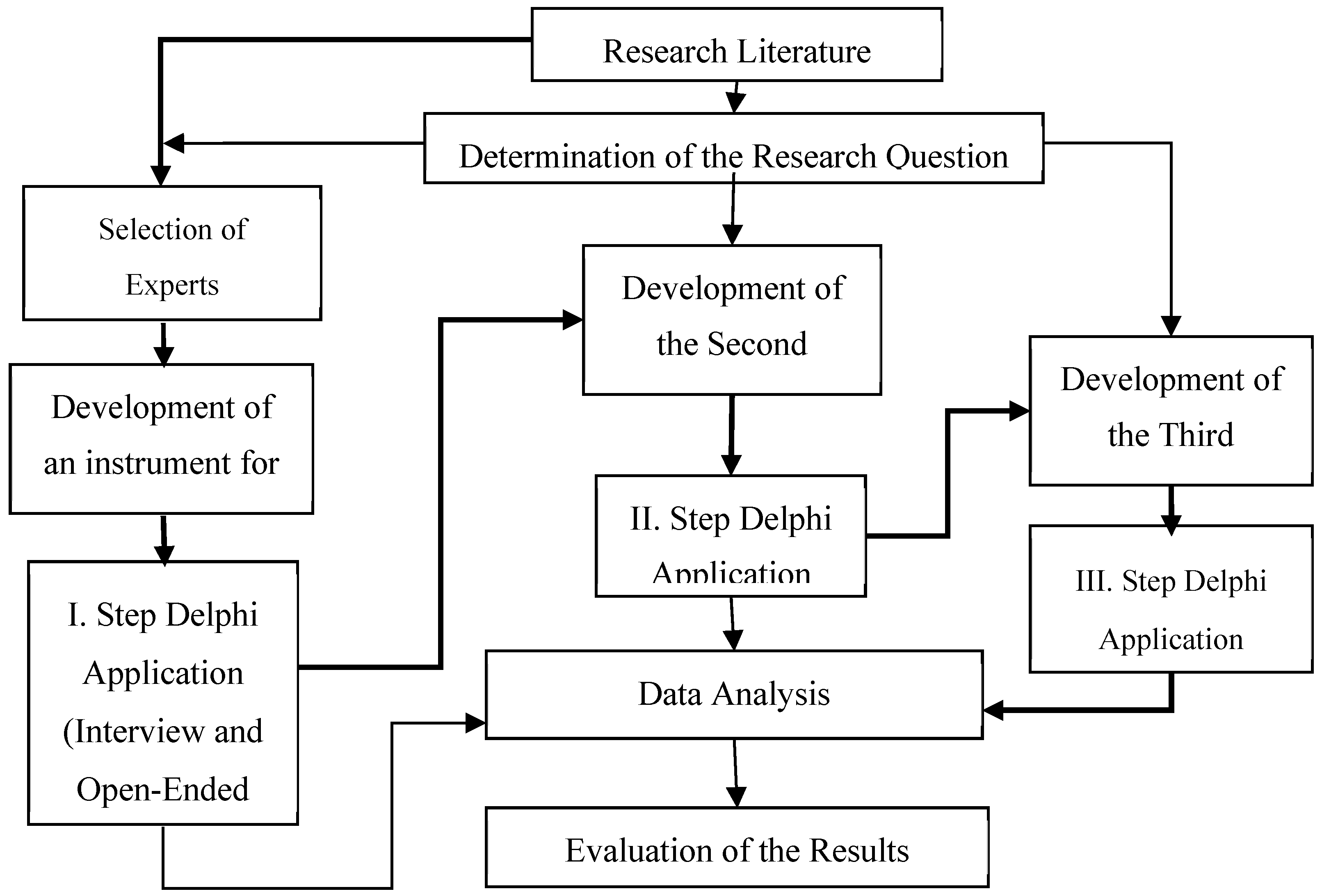

2.2. Process of the Delphi Study

2.2.1. First Round

2.2.2. Second Round

2.2.3. Third Round

2.3. Methods of Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- Environmental perceptions (attitude, responsibility, morals, etc.);

- Examples of environmentally-friendly behavior (such as saving and protecting natural resources, etc.);

- Nature of environmental concepts (ecosystem, ecology, and natural resources, etc.);

- Examples of environmental problems (global warming, climate change, and endangered species, etc.);

- Solutions for environmental problems (recycling and renewable energy, etc.);

- Sustainability (sustainable development and future, etc.);

- Social perspectives (interrelationship of environment, society, and technology, etc.).

5. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire for Delphi Study (Step-I)

- How would you define environmental literacy?

- What are the sub-dimensions of environmental literacy over the next 20 years?

- Which competencies (motivation, cognitive, social, and intention to action) should environmentally literate individuals have?

- Who is responsible for the promotion of the development of a qualified environmentally literate individual?

- What should be done to promote the development of a qualified literate environmental individual?

- Which topics (concepts and contexts) should be included in the curriculum and textbooks that promote the development of environmental literacy?

- Which teaching method(s) should be used to promote the development of qualified literate individuals?

References

- Roth, C.E. Environmental Literacy: Its Roots, Evolution and Directions in the 1990s; ERIC Clearinghouse for Science, Mathematics and Environmental Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrade Charter. A Global Framework for Environmental Education. 1975. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0001/000177/017772eb.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2017).

- Wright, T.S.A. Definitions and Frameworks for Environmental Sustainability in Higher Education. High. Educ. Policy 2002, 15, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.V. Environmental Education: A Delineation of Substantive Structure. Ph.D. Thesis, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education Final Report; UNESCO: Tbilisi, Georgia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO-UNEP. Outline International Strategy for Action in the Field of Environmental Education and Training for the 1990s. In Proceedings of the UNESCO-UNEP International Congress on Environmental Education and Training, Moscow, Russia, 17–21 August 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, W. Sustainable development and the biosphere. Teilhard Studies Number 23. American Teilhard Association for the Study of Man, or: The Ecology of Sustainable Development. Ecologist 1990, 20, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- McBeth, W.; Volk, T.L. The National Environmental Literacy Project: A Baseline Study of Middle Grade Students in the United States. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarini, M.S. Philosophical, epistemological, doctrinal and structural basis for international environmental education curriculum. In Proceedings of the International Best of Both Worlds Conference, Pretoria, South Africa, March 1998; Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED440819.pdf#page=265 (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- United Nations (UN). ACENDA 2l: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development; United Nations Publication: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://www.dataplan.info/img_upload/ 7bdb1584e3b8a53d337518d988763f8d/agenda21-earth-summit-the-united-nations-programme-of-action-from-rio_1.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Simmons, B. Standards for the Initial Preparation of Environmental Educators; North American Association for Environmental Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, D. The Thessaloniki Declaration: A Wake-Up Call for Environmental Education? J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE). Guidelines for Excellence K-12 Learning for Students, Parents, Educators, Home Schoolers, Administrators, Policy Makers, and the Public; NAAEE Publications and Membership Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schirnding, Y. The World Summit on Sustainable Development: Reaffirming the centrality of health. Glob. Health 2005, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Environmental Education. Final Report. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Environmental Education, Ahmedabad, India, 22–30 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, V.H.; Elster, D. German Students’ Environmental Literacy in Science Education Based on PISA Data. Sci. Educ. Int. 2018, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Disinger, J.; Roth, C. Environmental Literacy. ERIC/CSMEE Digest. Available online: http://www.ericdigests.org/1992-1/literacy.htm (accessed on 6 April 2018).

- Pfirman, S.; the AC-ERE. Complex Environmental Systems: Synthesis for Earth, Life, and Society in the 21st Century; A Report Summarizing a 10-Year Outlook in Environmental Research and Education for the National Science Foundation; National Science Foundation: Arlington, VA, USA, 2003; 68p.

- Gunckel, K.L.; Mohan, L.; Covitt, B.A.; Anderson, C.W. Addressing Challenges in Developing Learning Progressions for Environmental Science Literacy. In Learning Progressions in Science; Alonzo, A.C., Gotwals, A.W., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development in the European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/8461633/KS-04-17-780-EN-N.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- Simmons, B. Linking Environmental Literacy and the Next Generation Science Standards a Tool for Mapping an Integrated Curriculum; North American Association for Environmental Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Anderson, C.W. Environmental Literacy Learning Progressions, Knowledge Sharing Institute of the Center for Curriculum Studies in Science Washington. 2007. Available online: http://www.project2061.org/publications/2061connections/2007/media/KSIdocs/anderson_handout.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Sadler, T.D.; Amirshokoohi, A.; Kazempour, M.; Allspaw, K.M. Socioscience and ethics in science classrooms: Teacher perspectives and strategies. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2006, 43, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurusaki, B.K.; Anderson, C.W. Students’ Understanding of Connections between Human Engineered and Natural Environmental Systems. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2010, 5, 407–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hollweg, K.S.; Taylor, J.R.; Bybee, R.W.; Marcinkowski, T.J.; McBeth, W.C.; Zoido, P. Developing a Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy; North American Association for Environmental Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden, M. Grup Etkililigi Ögretim Tekniginin Ögrenci Başarısına Etkisi. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 1988, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, A. The Effect of Cooperative Learning Strategies on Elementary Students’ Science Achievement and Social Skills in Kuwait. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2011, 10, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, Q.; Batool, S. Effect of Cooperative Learning on Achievement of Students in General Science at Secondary Level. Int. Educ. Stud. 2012, 5, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapıcı, I.U.; Hevadanlı, M.; Oral, B. The Effect of Cooperative Learning and Traditional Teaching Methods on Students’ Attitudes and Achievement in Systematic of Seed Plants Laboratory Course. Pamukkale Univ. J. Educ. Fac. 2009, 26, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, A. The Effect of Inquiry-based Learning Method on Students’ Academic Achievement in Science Course. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, D.; Barendziak, T.; Haskamp, F.; Kastenholz, L. Raising Standards through INQUIRE in Pre-service Teacher Education. Sci. Educ. Int. 2014, 25, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D.O.; Lambeth, D.T.; Cox, J.T. Effects of using inquiry-based learning on science achievement for fifth-grade students. Asia-Pac. Forum Sci. Learn. Teach. 2015, 16, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, B.; Hemmer, L.; Kouzekanani, K. The Impact of Project-Based Learning on Minority Student Achievement: Implications for School Redesign. NCPEA Educ. Leadersh. Rev. Dr. Res. 2015, 2, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ergül, N.R.; Kargın, E.K. The Effect of Project Based Learning on Students’ Science Success. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 136, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.J. Educating for Environmental Literacy: The Environmental Content of the NSW Science Syllabuses, Student Conceptions of the Issues and Educating for the New Global Paradigm. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Bentley, WA, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Annu, S.; Sunita, M. Extracurricular Activities and Student’s Performance in Secondary School of Government and Private Schools. Int. J. Sociol. Anthropol. Res. 2015, 1, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Education Bureau. Guidelines on Extra-Curricular Activities in School. Available online: https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/sch-admin/admin/about-activities/sch-activities-guidelines/E_eca.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Simoncini, K.; Caltabiono, N. Young School-Aged Children’s Behaviour and Their Participation in Extra-Curricular Activities. Australas. J. Early Child. 2012, 37, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bakoban, R.A.; Aljarallah, S.A. Extracurricular activities and their effect on the student’s grade point average: Statistical study. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 10, 2737–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, V.H.; Elster, D. Comparison of the Main Determinants Affecting Environmental Literacy between Singapore, Estonia and Germany. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2018, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Seow, P.S.; Pan, G.S.S. A Literature Review of the Impact of Extracurricular Activities Participation on Students’ Academic Performance. J. Educ. Bus. 2014, 89, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucu, R.; Platis, M. Extra-Curriculum Activities Challenges and Opportunities. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 4249–4252. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, E.A.; Retallick, M.S. Undergraduate Involvement in Extracurricular Activities and Leadership Development in College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Students. J. Agric. Educ. 2012, 53, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.; Dumas, B.K.; Jones, C.; Mbarika, V.; Ong’oa, I.M. Extracurricular Activities and Academic Achievement: A Literature Review. Glob. Adv. Res. J. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 4, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Derous, E.; Ryan, A.M. When earning is beneficial for learning: The relation of employment and leisure activities to academic outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlove, K.J. The Impact of Extracurricular Athletic Activities on Academic Achievement, Disciplinary Referrals, and School Attendance among Hispanic Female 11th Grade Students. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shiveley, J. The Impact of Extracurricular Activity on Student Academic Performance. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.631.7263&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, M.J. The Online Teaching Skills and Best Practices of Virtual Classroom Teachers: A Mixed Method Delphi Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Klassen, A.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Clegg Smith, C. Best practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences; Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2011.

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Villiers, M.R.; Villiers, P.J.T.; Kent, A.P. Delphi Technique in Health Sciences Education Research. Med Teach. 2005, 27, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, C.H. Implementation of Delphi Technique in Educational Communication. J. Kurgu 1999, 16, 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Gencturk, E.; Akbas, Y. Defining Social Studies Teacher Education Geography Standards: An Implication of Delphi Technique. GUJGEF 2002, 33, 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore, R.; Flanagan, T.; Mcinnes, D.; Banks, D. The Delphi Method: Methodological Issues Arising from a Study Examining Factors Influencing the Publication or Non-Publication of Mental Health Nursing Research. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2016, 21, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Skulmoski, G.J.; Hartman, F.T.; Krahn, J. The Delphi Method for Graduate Research. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. 2007, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, W. The Delphi technique: A review. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2009, 16, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, S.; Hasson, F.; McKenna, H.P. A Critical Review of the Delphi Technique as a Research Methodology for Nursing. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2001, 38, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjil, R. Delphi in a Future Scenario Study on Mental Health and Mental Health Care. Futures 1992, 24, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Christensen, L. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qulitative, and Mixed Approaches; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, A.E. The State of Elementary Principalship as a Profession in Turkey: A Delphi Study. Pamukkale Univ. J. Educ. Fac. 2009, 26, 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An Experimental Application of the Delphi Method to the Use of Experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.E. Delphi Technique and its Uses in Educational Research. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. Fac. 2001, 20, 215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, V.H.; Elster, D. Environmental Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Pedagogical Content Knowledge: Teacher’s Professional Development as Environmental Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Literate Individuals in the Light of Experts’ Opinions. Sci. Educ. Int. 2019, 30, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, T. Desirable Science Education Findings from a Curricular Delphi Study on Scientific Literacy in Germany; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, J.B. Best Practices for Online Theological Ministry Preparation: A Delphi Method Study. Ph.D. Thesis, the Faculty of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville, KY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gülbahar, Y.; Alper, A. A Content Analysis of the Studies in Instructional Technologies Area, Ankara University. J. Fac. Educ. Sci. 2009, 42, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Tüzel, S. The Analysis of L1 Teaching Programs in England, Canada, the USA and Australia Regarding Media Literacy and Their Applicability to Turkish Language Teaching. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2013, 13, 2310–2316. [Google Scholar]

- Minner, D.; Klein, J. A Case for Advancing an Environmental Literacy Plan in Massachusetts: Phase I—A Summary of the Commonwealth’s Environment and Education Landscape. Available online: http://massmees.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/MassELP-Phase-I-Summary-FINAL.pdf. 2016 (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- North Carolina. Department of Environmental Quality. Smart Minds Greener Future North Carolina Environmental Literacy Plan; Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2017.

- Kaya, V.H.; Elster, D. Change in the Environmental Literacy of German Students in Science Education between 2006 and 2015. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 2017, 505–524. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Environmental Education Advisory Council. 2015 Report to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents /final2015neeacreport-08_7_2015_2.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Karimzadegan, H.; Meiboudi, H. Exploration of environmental literacy in science education curriculum in primary schools in Iran. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C. Educational Interventions That Improve Environmental Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 31, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reliability Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items | ||

| Question 1: Definition of environmental literacy | 0.70 | 5 | ||

| Question 2: Sub-dimensions of environmental literacy | 0.78 | 7 | ||

| Question 3: Competencies of environmental literacy | 0.92 | 10 | ||

| Question 4: Institutions and social groups responsible for the development of qualified environmentally literate individuals | 0.90 | 10 | ||

| Question 5: People responsible for the development of qualified environmentally literate individuals | 0.91 | 13 | ||

| Question 6: What to do to support the development of qualified environmental literacy | 0.92 | 11 | ||

| Question 7: Topics that should be included in the curriculum and textbooks for the development of environmental literacy | 0.85 | 7 | ||

| Question 8: Teaching methods for the development of environmental literacy | 0.82 | 11 | ||

| Question 9: Extra-curriculum activities for the development of environmental literacy | 0.86 | 7 | ||

| Total | 0.97 | 81 | ||

| Spearman-Brown Coefficient | Equal Length | 0.92 | ||

| Unequal Length | 0.92 | |||

| Consensus | Indicator of Consensus |

|---|---|

| Consensus Criteria | If median ≥ 5 and DBQ ≤ 1.5, If median ≥ 5 and DBQ ≤ 1.5 and 5–7 frequencies ≥ 70% |

| Consensus Not Reached | If median ≤ 3 and DBQ ≤ 1.5, If median ≤ 3 and DBQ ≤ 2.5 and 1–3 frequencies ≥ 70% |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Knowledge and understanding of environmental issues | 2.R. | 6.18 | 1.24 | 6.50 | 1.00 | 42 (95.5) | - | 2 (4.5) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.58 | 0.72 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Attitudes and concern towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.30 | 1.13 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (93.2) | - | 3 (6.8) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.45 | 1.18 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Morals and ethics towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.33 | 1.23 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 39 (90.7) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (7.0) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.55 | 0.85 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Intention to act with environmentally responsible behavior | 2.R. | 6.26 | 1.12 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 95.3 | - | 4.7 | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.53 | 0.82 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 29 (96.7) | - | 1 (3.3) | Yes | |

| * Improved skills to evaluate data, draw conclusions, and form opinions | 2.R. | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3.R. | 6.11 | 1.20 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 16 (84.2) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) | Yes | |

| Interrelationship of knowledge, understanding, attitude, morals and ethics, and intentions and behaviors towards the environment | 2.R. | 5.80 | 1.61 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 36 (81.8) | 4 (9.1) | 4 (9.1) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.03 | 1.49 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 30 (80.6) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (9.7) | No | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Knowledge and understanding about environmental issues | 2.R. | 6.23 | 0.74 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.16 | 1.21 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 27 (87) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | Yes | |

| “Legislation about environment” should be added to the above item * | 2.R. | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3.R. | 5.40 | 1.77 | 6.00 | 3.00 | 11 (73.4) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | No | |

| Environmental attitudes | 2.R. | 6.37 | 0.87 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (95.3) | 2 (4.7) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.48 | 0.77 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Environmental motivation | 2.R. | 6.23 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 39 (90.7) | 3 (7.0) | 1 (2.3) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.48 | 0.85 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Morals and ethics related to the environment | 2.R. | 6.37 | 0.85 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (95.3) | 2 (4.7) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.55 | 0.62 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Intention to act in an environmentally-friendly manner | 2.R. | 6.42 | 0.76 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 42 (97.7) | 1 (2.3) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.55 | 0.81 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Environmentally-friendly behaviors | 2.R. | 6.55 | 0.63 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 42 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.74 | 0.45 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Sustainability | 2.R. | 6.48 | 0.85 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 42 (95.5) | 2 (4.5) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.77 | 0.56 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Knowledge and understanding about environment issues | 2.R. | 6.50 | 0.75 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.68 | 0.70 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Responsibility towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.54 | 0.78 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 42 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.71 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Awareness towards environmental issues | 2.R. | 6.56 | 0.67 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 42 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.61 | 0.62 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Motivation towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.42 | 0.77 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.49 | 0.81 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Morals and ethics towards environmental issues | 2.R. | 6.46 | 0.81 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.58 | 0.89 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Social engagement related to the environment | 2.R. | 6.12 | 1.05 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 39 (95.2) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.36 | 1.08 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Intention to act to protect the environment | 2.R. | 6.49 | 0.81 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (97.6) | - | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.88 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Positive behavior towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.66 | 0.66 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.87 | 0.43 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Sustainable knowledge about the environment | 2.R. | 6.44 | 0.81 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 40 (95.1) | 2 (4.9) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.74 | 0.68 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Concrete sustainable activities towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.07 | 1.03 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 37 (90.2) | 4 (9.8) | - | No |

| 3.R. | 6.42 | 0.92 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | - | Yes | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Social environment (family, friends, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.29 | 1.03 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 40 (97.6) | - | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.42 | 1.09 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| School (formal education) | 2.R. | 6.46 | 0.98 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 40 (97.6) | - | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.58 | 0.99 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| University | 2.R. | 6.39 | 0.80 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 100 | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.32 | 0.87 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| State | 2.R. | 5.88 | 1.49 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 36 (87.8) | 1 (2.4) | 4 (9.8) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.19 | 1.35 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 28 (90.3) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Ministry of education | 2.R. | 6.27 | 1.23 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 35 (85.4) | 5 (12.2) | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.48 | 1.15 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 28 (90.3) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Public departments | 2.R. | 5.98 | 1.28 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 35 (85.3) | 4 (9.8) | 2 (4.9) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.00 | 1.48 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 25 (80.6) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (6.5) | Yes | |

| Municipalities | 2.R. | 6.34 | 1.11 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 37 (90.2) | 2 (4.9) | 2 (4.9) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.32 | 1.30 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 27 (87.1) | 2 (6.4) | 2 (6.4) | Yes | |

| Industries | 2.R. | 5.83 | 1.86 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 34 (83.0) | 1 (2.4) | 6 (14.6) | No |

| 3.R. | 5.90 | 1.87 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 27 (83.9) | - | 5 (16.1) | Yes | |

| Citizen associations | 2.R. | 6.10 | 1.43 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 36 (87.8) | 3 (7.4) | 2 (4.8) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.13 | 1.18 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 29 (90.3) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Public media | 2.R. | 6.39 | 1.05 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 37 (90.3) | 3 (7.3) | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.57 | 0.77 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Family (mother, father, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.49 | 0.87 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 40 (97.6) | - | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.45 | 0.96 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | - | 1 (3.2) | Yes | |

| Friends | 2.R. | 5.82 | 1.21 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 36 (92.3) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.1) | No |

| 3.R. | 5.67 | 1.56 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 25 (80.0) | 4 (13.3) | 2 (6.7) | No | |

| Individual (themselves) | 2.R. | 6.43 | 1.20 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 38 (95.0) | - | 2 (5.0) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.40 | 1.33 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 28 (93.3) | - | 2 (6.7) | Yes | |

| Educators | 2.R. | 6.63 | 0.66 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.61 | 0.80 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | - | Yes | |

| Academics | 2.R. | 6.27 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 37 (90.2) | 4 (9.8) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.26 | 1.03 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | - | Yes | |

| Scientists | 2.R. | 6.25 | 1.24 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 35 (87.5) | 4 (10.0) | 1 (2.5) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.23 | 1.28 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 26 (87.7) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (3.3) | Yes | |

| Teachers | 2.R. | 6.71 | 0.68 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.71 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Employees who work at School | 2.R. | 5.80 | 1.42 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 33 (82.5) | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.5) | No |

| 3.R. | 5.77 | 1.23 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 25 (83.4) | 4 (13.3) | 1 (3.3) | No | |

| Country administrators | 2.R. | 5.88 | 1.68 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 35 (85.4) | - | 6 (14.6) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.07 | 1.50 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 27 (87.1) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | No | |

| Policy makers | 2.R. | 5.80 | 1.79 | 7.00 | 1.75 | 33 (82.5) | 1 (2.5) | 6 (15.0) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.10 | 1.63 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 25 (83.3) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (10.0) | Yes | |

| Entrepreneurs | 2.R. | 5.56 | 1.92 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 32 (78.0) | 2 (4.9) | 7 (17.1) | No |

| 3.R. | 5.73 | 1.83 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 24 (80.0) | 1 (3.3) | 5 (16.7) | No | |

| Business people | 2.R. | 5.58 | 1.80 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 32 (80.0) | 3 (7.5) | 5 (12.5) | No |

| 3.R. | 5.60 | 1.27 | 6.50 | 2.00 | 25 (83.3) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (13.3) | No | |

| Artists | 2.R. | 6.13 | 1.44 | 7.00 | 1.75 | 33 (82.5) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (5.0) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.03 | 1.87 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 26 (86.7) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (3.3) | No | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| The family should inform their children about environmental issues | 2.R. | 6.49 | 0.93 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 39 (95.2) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.68 | 0.79 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| The family should support their children to gain morals and ethics towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.56 | 0.78 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.61 | 0.80 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| The family should support their children to gain positive attitudes towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.49 | 0.90 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 39 (95.1) | 2 (4.9) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.71 | 0.69 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Teachers should inform their students about environmental issues | 2.R. | 6.71 | 0.56 | 7.00 | 0.50 | 41 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.81 | 0.48 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Teachers should support their students to gain morals and ethics towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.66 | 0.69 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 41 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.68 | 0.60 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Teachers should support their students to gain positive attitudes towards the environment | 2.R. | 6.66 | 0.73 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.74 | 0.51 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Teachers should support their students to gain intentions to act with and show environmentally-friendly behavior | 2.R. | 6.76 | 0.62 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.71 | 0.59 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| In science curricula, more environmental topics and their practices should be included | 2.R. | 6.39 | 0.97 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 38 (92.7) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.52 | 0.81 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Governments should support the qualifications of their teachers. | 2.R. | 6.44 | 1.21 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 37 (94.9) | - | 2 (5.1) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.40 | 1.30 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 29 (93.3) | - | 2 (6.7) | Yes | |

| Non-government organizations should support individuals to take part in social, civil, and societal initiatives | 2.R. | 6.32 | 1.06 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 38 (92.7) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.48 | 0.89 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Public Media (such as newspaper, TV, etc.) should support individuals to learn about environmental issues. | 2.R. | 6.37 | 1.07 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 38 (92.7) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.68 | 0.65 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Environmental perceptions (attitude, responsibilities, morals, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.46 | 0.93 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 35 (92.2) | 3 (7.8) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.55 | 0.85 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | - | Yes | |

| Examples of environmentally-friendly behavior | 2.R. | 6.69 | 0.62 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 35 (97.2) | 1 (2.8) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.55 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Nature of environmental concepts (ecosystems, ecology, natural resources, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.62 | 0.64 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 38 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.77 | 0.43 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Examples of environmental problems (global warming, climate change, endangered species, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.76 | 0.55 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 38 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.90 | 0.40 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Solutions for environmental problems (recycling, renewable energy, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.60 | 0.73 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 37 (97.3) | 1 (2.7) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.61 | 0.84 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | - | Yes | |

| Sustainability (sustainable development and future, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.60 | 0.69 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 38 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.77 | 0.50 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Social perspectives (interrelationship of environment, society, and technology, etc.) | 2.R. | 6.38 | 1.04 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 35 (91.9) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.7) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.61 | 0.76 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Experiments | 2.R. | 6.23 | 1.09 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 33 (94.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.28 | 0.84 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 28 (93.1) | 2 (6.9) | - | Yes | |

| Knowledge transmission (direct instruction, expository instruction) | 2.R. | 5.14 | 1.68 | 5.00 | 0.25 | 27 (77.8) | 1 (2.8) | 7 (19.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 4.23 | 2.13 | 5.00 | 3.25 | 16 (53.3) | 3 (10.0) | 11 (36.7) | No | |

| Project-based learning | 2.R. | 6.61 | 0.65 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 36 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.55 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Documentaries and videos | 2.R. | 6.00 | 0.88 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 35 (94.6) | 2 (5.4) | - | No |

| 3.R. | 5.87 | 1.20 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 29 (93.6) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | No | |

| Context-based learning | 2.R. | 6.08 | 1.06 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 34 (91.9) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.7) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.16 | 0.90 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | - | Yes | |

| Problem-based learning | 2.R. | 6.54 | 0.77 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 36 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.66 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Different discussion methods | 2.R. | 6.41 | 0.69 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 36 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.58 | 0.62 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Inquiry-based learning | 2.R. | 6.57 | 0.80 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 35 (97.3) | 1 (2.7) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.61 | 0.76 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Out-of-school activities | 2.R. | 6.62 | 0.76 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 36 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.68 | 0.70 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Hands-on experience | 2.R. | 6.65 | 0.89 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 33 (91.9) | 3 (8.1) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.84 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | Yes | ||

| Collaborative learning | 2.R. | 6.60 | 0.64 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 36 (100) | - | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.65 | 0.61 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

| Item | Round | Sd | Med | DBQ | Responses f (%) | Cons Based on Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Neut | No Cons | |||||||

| Watch TV programs about the environment | 2.R. | 6.19 | 0.94 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 36 (97.3) | 1 (2.7) | - | No |

| 3.R. | 5.97 | 1.33 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 28 (90.3) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | No | |

| Visit web sites of environment organizations | 2.R. | 5.73 | 1.19 | 6.00 | 1.50 | 35 (94.6) | - | 2 (5.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 5.51 | 1.21 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 27 (87.0) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | Yes | |

| Participate in environment clubs and activities | 2.R. | 6.24 | 0.86 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 35 (94.6) | 2 (5.4) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.58 | 0.77 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | - | Yes | |

| Visit botanical garden | 2.R. | 6.27 | 0.96 | 7.00 | 1.50 | 35 (97.3) | 2 (4.7) | - | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.10 | 0.96 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 28 (93.3) | 2 (6.7) | - | No | |

| Read a book or newspaper about the environment | 2.R. | 6.11 | 1.02 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 34 (91.9) | 3 (8.1) | - | No |

| 3.R. | 6.03 | 1.14 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | - | No | |

| Visit museums of science and the arts | 2.R. | 6.06 | 1.22 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 32 (88.4) | 2 (5.8) | 2 (5.8) | No |

| 3.R. | 6.13 | 0.92 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | - | Yes | |

| Field trips and excursions | 2.R. | 6.33 | 1.24 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 35 (94.6) | - | 2 (5.4) | Yes |

| 3.R. | 6.67 | 0.61 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 31 (100) | - | - | Yes | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaya, V.H.; Elster, D. A Critical Consideration of Environmental Literacy: Concepts, Contexts, and Competencies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061581

Kaya VH, Elster D. A Critical Consideration of Environmental Literacy: Concepts, Contexts, and Competencies. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061581

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaya, Volkan Hasan, and Doris Elster. 2019. "A Critical Consideration of Environmental Literacy: Concepts, Contexts, and Competencies" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061581

APA StyleKaya, V. H., & Elster, D. (2019). A Critical Consideration of Environmental Literacy: Concepts, Contexts, and Competencies. Sustainability, 11(6), 1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061581