Regulatory Measurements in Policy Coordinated Practices: The Case of Promoting Renewable Energy and Cleaner Transport in Sweden

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. Short Introduction to the Development of Regulatory Impact Assessment and CBA

2.2. Policy Coordination

3. Materials and Methods

4. The Swedish Government System

Sweden will continue to be a leading country in the transition to sustainable development. The government’s overall goal of environmental policy is that the next generation to hand over a Sweden where the major environmental problems have been solved.[40] (p. 7)

5. Results

5.1. Close Relationship between the National Government and Agencies in Discussion of EU Directives

5.1.1. Limited Use of Impact Assessment that Includes Cost-benefit Analysis

The complexity of the adjustment resulting from a package of instruments in the form of general policy instruments and instruments targeted at specific sectors of society makes retrospective assessments of individual instruments is very difficult to implement. To distinguish certain measures to a specific instrument or determine the amount of emission reductions in a sector…is many times impossible.[41] (p. 72)

...the problem of assessing the cost-effectiveness of the policy has been difficult in [38] and stopped at the likely effects and theoretical reasoning. This means that the cost-effectiveness of the instruments who has been part of the Swedish energy and climate policy has not been sufficiently explicitly described and evaluated.[54] (p. 10)

5.1.2. Instruments are Argued to be Effective, in Spite of Lack of Impact Assessment Evaluations

“The local commitment for climate work is judged in the long term to be a major driver of a transition to sustainability” [41] (p. 260). ….“Some environmental effects of subsidies are difficult to calculate especially in the longer term”.[41] (p. 260)

The instruments that are of importance for the Swedish climate strategy has gradually evolved since the late 1980s. It includes not only decisions on climate policy but largely also in the context of energy policy and to some extent in the transport and waste policy. This means that the instruments that have been important to limit climate change in many cases was introduced to achieve other societal goals.[56] (p. 12)

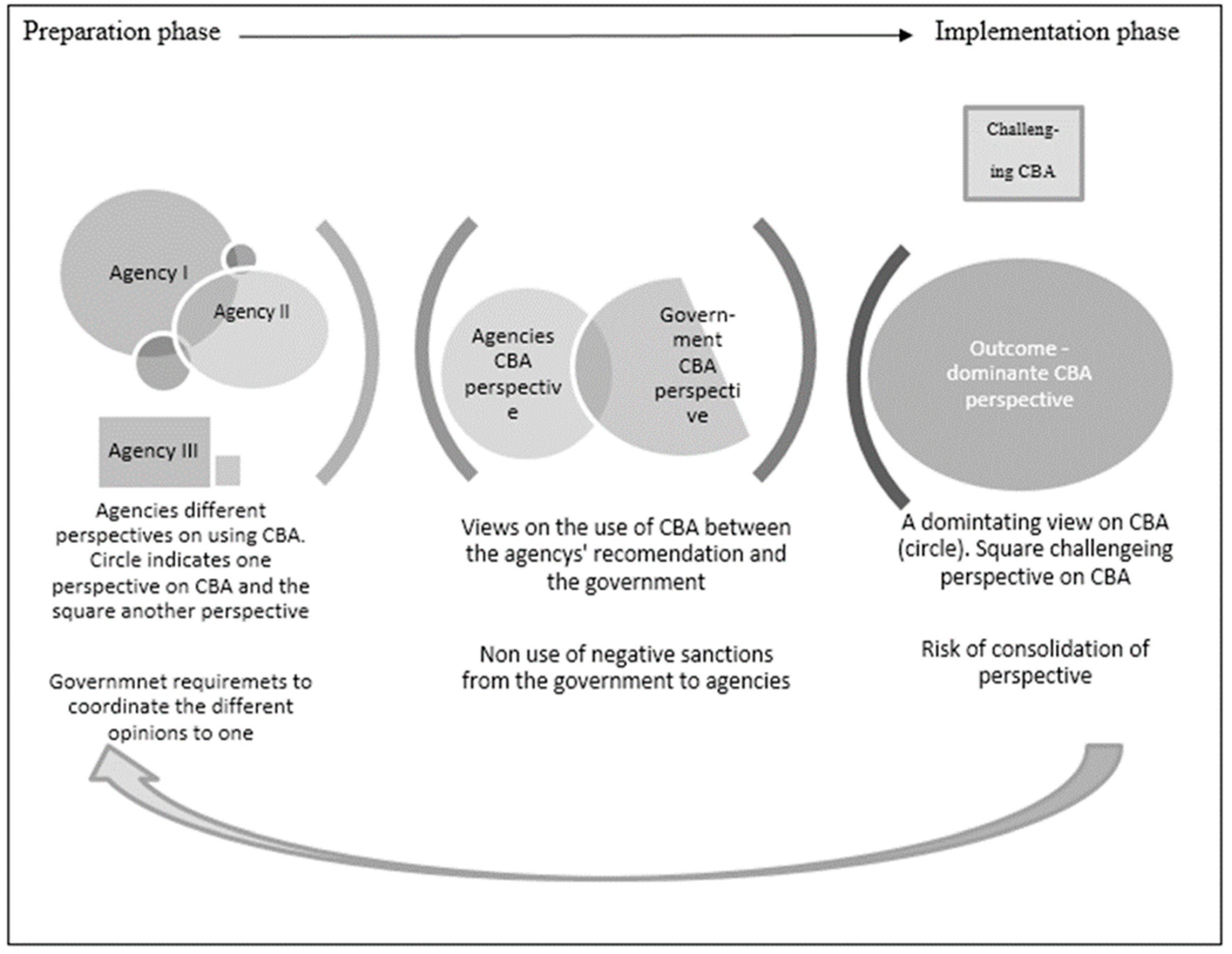

5.2. New Coordination Practices May Challenge the Existing (non-) Use of CBA, but Old Assumptions about the CBA Method Remain

The Commission’s calculations are based on the assumption that adequate financing is available for the various investments needed initially, even if the measures are expected to be profitable over time due to reduced energy costs for end customers.[57] (p. 11)

The Government encourages the European Commission to deepen the analysis of reported policy options, this includes short- and long-term socio-economic effects and begin the design of a climate and energy policy framework beyond 2020 in which the EU Commission’s consideration of renewable energy included. Structural parts of this framework should be cost instruments leading to sub-optimization is as far as possible avoided and synergies exploited. The framework should be based on an in-depth analysis, including considering how the goals and instruments for renewable energy affects the cost-efficiency in the fulfillment of the long-term goal of climate policy.[58] (p. 8)

During the year [2012], cost-benefit analysis has been a prioritized area at the Swedish Energy Agency. Personnel with this competence has been recruited and methods have been developed...There has been work with creating a process of when, how and why cost-benefit analysis should be included in the agency’s work, this by establishing a routine and a checklist.[62] (p. 84)

The analysis of climate policy instruments lacks the long-term perspective that is necessary in order to achieve a cost-effective solution to climate change. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency have a dissenting opinion to some conclusions in the report. These include interaction between climate and energy policy objectives and energy policy objectives more expensive climate policy. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency also believes that other policy instruments than economic instruments, is insufficiently treated in the report.[63] (pp. 211–212)

The National Institute of Economic Research, The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and The Swedish Energy Agency was together appointed by the government to make impact assessment…The agencies have different roles, responsibilities and methods for conducting our work. This can affect how well we address the various issues in our findings and conclusions. Therefore, we present below brief each authority’s overall mission linked to the issues analyzed in this government mandate.[64] (p.4)

The valuation of costs to society is associated with great uncertainty. Partly because the transport system and the impact on society change over time and partly because the knowledge about the various effects of traffic is rarely complete as well as the methods used to evaluate these effects.[65] (p. 41)

6. Discussion: Policy-coordinated and Consensus-Based Policymaking—A Hindrance to Using Cost-benefit Analysis?

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The European Commission. Transport Emissions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport_en (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Dunlop, C.A.; Maggetti, M.; Radaelli, C.M.; Russel, D. The many uses of regulatory impact assessment: A meta-analysis of EU and UK cases. Regul. Gov. 2012, 6, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Economic Surveys: Sweden 2017; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cecot, C.; Hahn, R.; Renda, A.; Schrefler, L. An evaluation of the quality of impact assessment in the European Union with lessons for the US and the EU. Regul. Gov. 2008, 2, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Impact Assessment. 2018. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/impact/index_en.htm (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Lodge, M.; Wegrich, K. Managing Regulation: Regulatory Analysis, Politics and Policy; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012; pp. 192–220. [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli, C.M. Rationality, Power, Management and Symbols: Four Images of Regulatory Impact Assessment. Scand. Political Stud. 2010, 33, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOU. Kraftsamling för Framtidens Energi; Statens offentliga utredningar, 0375–250X, 2017:2; Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nerhagen, L.; Forsstedt, S. Regulating Transport. The possible role of regulatory impact assessment in Swedish transport planning. In ITF Discussion Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Petersson, O. Rational politics: Commissions of inquiry and the referral system in Sweden. In The Oxford Handbook of Swedish Politics; Pierre, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 650–662. [Google Scholar]

- Finansdepartementet. Tänk Efter Före. ESO-Rapport 2018: En ESO-Rapport Om Samhällsekonomiska Konsekvensanalyser; Norstedts Juridik AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

- Radaelli, C.M. Getting to grips with quality in the diffusion of regulatory impact assessment in Europe. Public Money Manag. 2004, 24, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, C.M. Diffusion without convergence: How political context shapes the adoption of regulatory impact assessment. J. Eur. Public Policy 2005, 12, 924–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renda, A. Impact Assessment in the EU: The State of the Art and the Art of the State; Centre for European Policy Studies (Ceps): Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rissi, C.; Sager, F. Types of knowledge utilization of regulatory impact assessments: Evidence from Swiss policymaking. Regul. Gov. 2013, 7, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P. Cost-benefit analyses of transportation investments. J. Crit. Realism 2006, 5, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Skamris Holm, M.K.; Buhl, S.L. How common and how large are cost overruns in transport infrastructure projects? Transp. Rev. 2003, 23, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Börjesson, M.; Eliasson, M.; Lundberg, M. Is CBA ranking of transport investments robust? J. Transp. Econ. Policy 2014, 48, 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S. 28 The evolution of cost–benefit analysis in US regulatory decisionmaking. In Handbook on the Politics of Regulation; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2011; p. 385. [Google Scholar]

- Casullo, L.; Zhivov, N. Assessing Regulatory Changes in the Transport Sector. An Introduction; Discussion Paper No. 2017-05; International Transport Forum at the OECD: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Further Developments and Policy Use; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 21–452. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo, D. Regulatory Impact Analysis in OECD Countries. Challenges for Developing Countries; South Asian-Third High Level Investment Roundtable: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2005; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Oberthür, S.; Stokke, O.S. Managing Institutional Complexity: Regime Interplay and Global Environmental Change; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, C. Joined-up Government: A survey. Polit. Stud. Rev. 2003, 1, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Institutional interplay: The environmental consequences of cross-scale interactions. In National Research Council. The Drama of the Commons; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Knill, C. Explaining cross-national variance in administrative reform: Autonomous versus instrumental bureaucracies. J. Public Policy 1999, 19, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Læreid, P. The Whole-of-Government Approach: Regulation, Performance, and Public-sector Reform; Rokkansenteret: Bergen, Norway, 2006; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, G.; Spyridonidis, D. Interpretation of multiple institutional logics on the ground: Actors’ position, their agency and situational constraints in professionalized contexts. Organ. Stud. 2016, 37, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lownpes, V. Varieties of new institutionalism: A critical appraisal. Public Adm. 1996, 74, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Olsen, J. Elaborating the “new institutionalism”. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions; Binder, S.A., Rhodes, R.A.W., Rockman, B.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2008; Online Publication: 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S.I.; Kok, M.T.J. Interplay Management in the Climate, Energy, and Development Nexus. In Managing Institutional Complexity: Regime Interplay and Global Environmental Change; Oberthür, S., Stokke, O.S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 285–312. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, T. Policy coordination under minority and majority rule. In The Oxford Handbook of Swedish Politics; Pierre, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 663–678. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty, W.; Hovden, W. Environmental policy integration: Towards an analytical framework. Environ. Polit. 2003, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennøy, A.; Hansson, L.; Lissandrello, E.; Næss, P. How planners’ use and non-use of expert knowledge affect the goal achievement potential of plans: Experiences from strategic land-use and transport planning processes in three Scandinavian cities. Prog. Plan. 2016, 109, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierson, P. Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, C.L. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? Pearson: Frenchs Forest, Australia, 2009; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, T.; Bäck, H. Governing and Governance in Sweden; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wockelberg, H. Political servants or independent experts? A comparative study of bureaucratic role perceptions and the implementation of EU law in Denmark and Sweden. J. Eur. Integr. 2014, 36, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Swedish Government Declaration. Available online: https://www.regeringen.se/informationsmaterial/2002/10/regeringsforklaringen-1-oktober-2002/ (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Utvärdering av Styrmedel i Klimatpolitiken: Delrapport 2 i Energimyndighetens och Naturvårdsverkets underlag till Kontrollstation 2004; Rapport 1403-1892, 2004:21; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2004.

- Strategin för Effektivare Energianvändning och Transporter EET: Underlag till Miljömålsrådets Fördjupade Utvärdering av Miljökvalitetsmålen; Rapport 0282-7298, 5777; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- Från Verksförordning till Myndighetsförordning: Betänkande; Statens offentliga utredningar, 0375–250X, 2004:23; Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004.

- Förordning (2007:1244) om Konsekvensutredning vid Regelgivning; Svensk Författningssamling (SFS) nr: 2007:1244; Swedish Government: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- The Directive 2009/28/EC on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- Årsredovisning 2002; ER/Energimyndigheten, 1403-1892, 2003:8; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2003.

- Årsredovisning 2003; ER/Energimyndigheten, 1403-1892, 2004:3; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2004.

- Årsredovisning 2004; ER/Energimyndigheten, 1403-1892, 2005:1; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2005.

- Årsredovisning 2006; ER/Energimyndigheten, 1403-1892, 2007:01; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2007.

- SOU. Förnybara Fordonsbränslen: Nationellt mål för 2005 och hur Tillgängligheten av Dessa Bränslen kan ökas: Delbetänkande; Statens offentliga utredningar, 0375–250X, 2004:4.; Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Regleringsbrev för Budgetåret 2004 Avseende Naturvårdsverket; The Swedish Government: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004.

- Styrmedel i Klimatpolitiken: Delrapport 2 i Energimyndighetens och Naturvårdsverkets underlag till Kontrollstation 2008; Rapport 1403-1892, 2007:28; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- Underlag till Kontrollstation 2015: Analys av Möjligheterna att nå de av Riksdagen Beslutade Klimat- och Energipolitiska Målen till år 2020: Naturvårdsverkets och Energimyndighetens Redovisning av Uppdrag Från Regeringen; Rapport 2014:17; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2014.

- Kostnadseffektiva Styrmedel i Den Svenska Klimat- Och Energipolitiken? Metodologiska Frågeställningar och Empiriska Tillämpningar; Specialstudie Nr 8.; Konjunkturinstitutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005.

- Styrmedels Effektivitet i den Svenska Klimatstrategin; Rapport 0282-7298, 5286; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003.

- Konsekvensanalys av Klimatmål: Delrapport 4 i Energimyndighetens och Naturvårdsverkets underlag till Kontrollstation 2008; Rapport 1403-1892, 2007:30; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- Förslag till Energieffektiviseringsdirektiv. Faktapromemoria 2010/11:FPM141; Regeringskansliet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010.

- Strategi om Förnybar Energi. Faktapromemoria 2012/13:FPM14; Regeringskansliet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012.

- Sveriges Första Rapport om Utvecklingen av Förnybar Energi Enligt Artikel 22 i Direktiv 2009/28/EG; The Swedish Government: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014.

- Broberg, T. En Samhällsekonomisk Granskning av Klimatberedningens Handlingsplan för Svensk Klimatpolitik; Rapport, 1650–1996X, 18; Konjunkturinstitutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Konsekvensbeskrivning av Styrmedel i Strategin för Effektivare Energianvändning och Transporter EET; Rapport 0282-7298, 5778; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- Årsredovisning 2012; ER/Energimyndigheten, 1403-1892, 2013:01; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2013.

- Miljö, Ekonomi och Politik; Konjunkturinstitutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012.

- Konsekvensanalyser av EU:s Klimatoch Energiramverk till 2030. Energimyndighetens, Konjunkturinstitutets och Naturvårdsverkets Redovisning av Uppdrag Från Regeringen; Energimyndigheten, Konjunkturinstitutet, Naturvårdsverket: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2014.

- Strategisk Plan för Omställning av Transportsektorn till Fossilfrihet; Rapport 2007:07; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2017.

- Redovisning av Effektkällor; Rapport 2007:13; Energimyndigheten: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2017.

- Sundström, G. Seconded national experts as part of early mover strategies in the European Union: The case of Sweden. J. Eur. Integr. 2016, 38, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analyser och Utvärderingar för Effektiv Styrning; Norstedts Juridik: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

| Type of source | Description 1 |

|---|---|

| Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU series) | Before the Government can draw up a legislative proposal, the matter in question must be analyzed and evaluated. The task may be assigned to a commission of inquiry or a one-man committee. The conclusions are published in the Swedish Government Official Reports series. |

| Ministry Publications Series (Ds) and Government Office’s memorandums. | The government can investigate a question within the Government Offices. Conclusions and proposals are published in the department series (Ds) or as a Government Office’s memorandum. |

| Ordinance explanatory note | The government explain new rules in a particular regulation and give notice of how the regulation is to be interpreted and applied. |

| Government bills | The government’s draft of the bill that will be submitted to the Swedish Parliament. |

| Swedish Government Offices Yearbook on the work with EU | The yearbook contains a description of the work with EU, decisions and events. The report is presented annually in the form of a letter submitted by the Government to the Swedish Parliament. |

| Written communications | Written communication comes in various forms:

|

| Reports and statements of opinion from the parliamentary committees | Committee reports are proposals from the parliamentary committees. The committees also draft statements on various EU proposals. |

| Explanatory memoranda on EU proposals | The Government informs the Parliament of topical EU issues by submitting explanatory memoranda to the Parliament. These describe proposals put forward by the EU and the Government informs the Parliament of its opinion on the proposals and in what way it thinks Sweden should work with the proposal. |

| Records from meetings of the Committee on EU Affairs | The Government is obliged to consult the Swedish Parliament on matters relating to the EU and what line of policy Sweden should take in the EU. This is done at the Committee on EU Affairs. |

| Annual reports from the Committee on EU Affairs | The annual reports contain yearly summaries of the Committee on EU Affairs activities. |

| Swedish Laws and EU directives | Laws are rules that everyone living in a country is obliged to comply with. |

| European Commission, "COM documents" | There are various kinds of COM documents:

|

| Reports and statements from government ministries | Reports, speeches, articles and press releases from the ministers and their departments. |

| Government Agency reports | Reports written by Swedish Agencies. They take various forms. It can be evaluations of government policies and initiatives. Reports can also be used in preparation for new policy proposals. |

| Annual reports from government agencies | Yearly reports describing the work that have been done at an agency. |

| Round of opinion, referrals | A government body ask relevant authorities, organizations, municipalities and other stakeholders to submit comments on a proposal. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hansson, L.; Nerhagen, L. Regulatory Measurements in Policy Coordinated Practices: The Case of Promoting Renewable Energy and Cleaner Transport in Sweden. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061687

Hansson L, Nerhagen L. Regulatory Measurements in Policy Coordinated Practices: The Case of Promoting Renewable Energy and Cleaner Transport in Sweden. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061687

Chicago/Turabian StyleHansson, Lisa, and Lena Nerhagen. 2019. "Regulatory Measurements in Policy Coordinated Practices: The Case of Promoting Renewable Energy and Cleaner Transport in Sweden" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061687

APA StyleHansson, L., & Nerhagen, L. (2019). Regulatory Measurements in Policy Coordinated Practices: The Case of Promoting Renewable Energy and Cleaner Transport in Sweden. Sustainability, 11(6), 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061687