Residents’ Attitudes towards Overtourism from the Perspective of Tourism Impacts and Cooperation—The Case of Ljubljana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

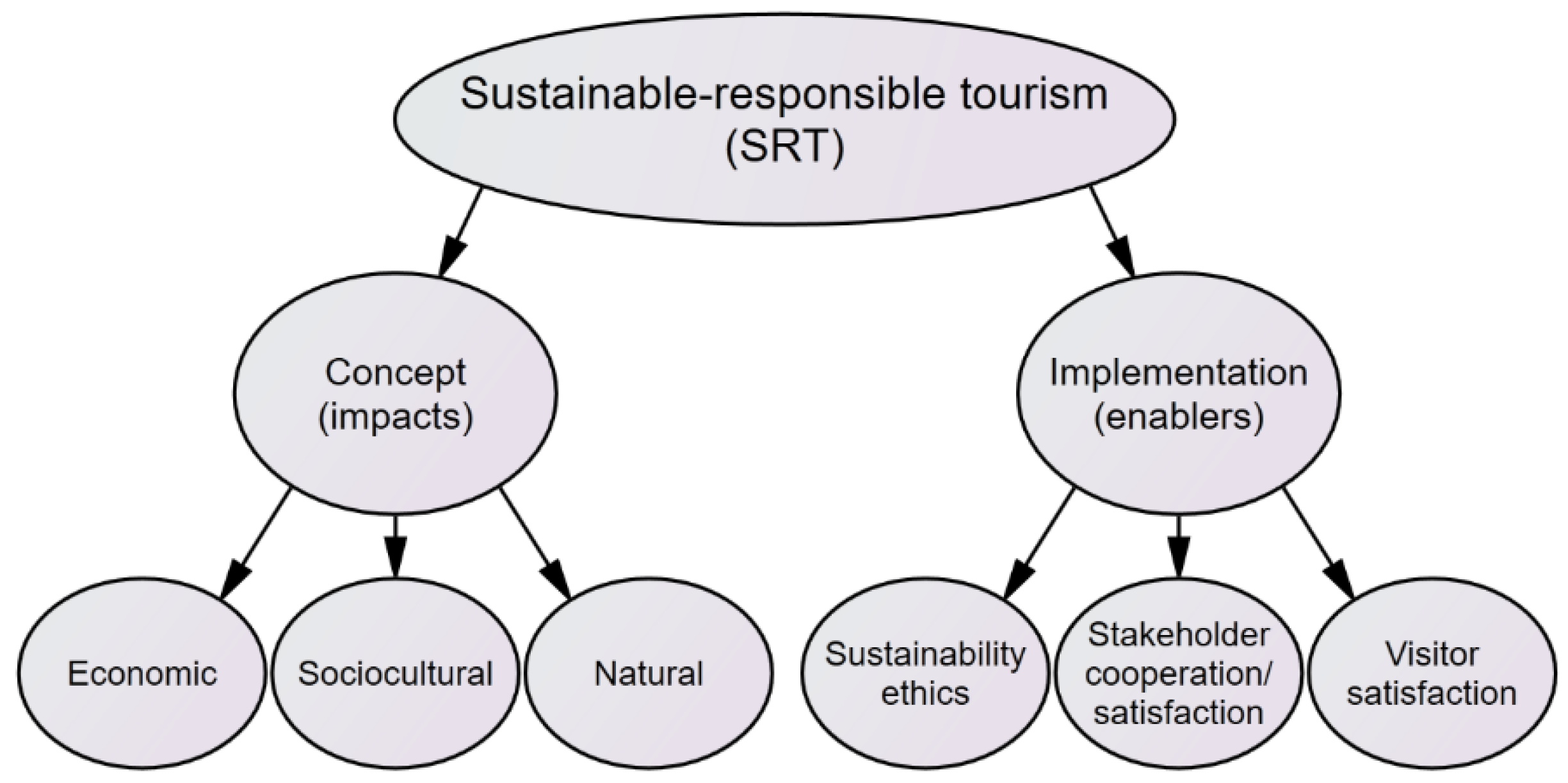

2. Sustainable-Responsible Tourism

- (1)

- The conceptual impacts must be taken into account

- (2)

- Responsible actions for implementing these (positive) sustainability impacts in real life must be executed.

- (1)

- First bubble illustrates sustainable tourism that must be based on an awareness of full sustainability and on sustainability ethics, supported by environmental education, knowledge and values, with full awareness about sustainability issues on the part of all stakeholders on both the demand and supply sides. The same ‘’Sustainability ethics’’ bubble (Figure 1) may incorporate more detailed tourism capacities, such as norms, legislation, etc. [5].

- (2)

- Second enabler bubble relates to the dimension, which we call ‘stakeholder cooperation/satisfaction’ (Figure 1). More specifically, sustainability implementation requires the informed participation of all relevant destination stakeholders, their cooperation and consensus, a critical mass and strong political leadership, governance and, especially relevant for this paper, the support of local residents and visitors [5,15].

- (3)

- Third implementation bubble, as presented in our SRT model (Figure 1) reminds us that tourism should maintain a high level of visitor satisfaction (demand side), thereby meeting market needs [12], in order to be sustained over time. Indeed, tourism development needs the active and cooperative participation of all stakeholders. The implementation of sustainability needs critical mass and consensus on all its dimensions, including growth and size of tourism visitation and scale of positive and negative tourism impacts. Among the destination’s tourism stakeholders, local residents and their attitude towards tourism are becoming increasingly important. Based on the social exchange theory, local residents’ disappointment and irritation with tourism impacts can deter or stop the development of tourism with actions against tourism development. The more local residents gain from tourism, the more motivated they are to support tourism activities and protect the destination’s natural and sociocultural environment [16,17,18].

3. New Tourism Phenomena

3.1. Over- and Anti-tourism

- (1)

- The first refers to the intellectual and cultural responses to a negative connotation of the words ‘tourist’ and ‘tourism’ [31] and becomes the antithesis of everything that is known as ‘touristic’. The idea builds on the critique of growing (mass) tourism and tourism consumerism and profitability and dissociation from belonging to it. It distinguishes the ‘righteous traveler from corrupt’, vulgar and ignorant tourists [32]. Righteous travelers behave differently from ‘ordinary’ tourists and are authentic and unique experience seekers [33], travel with an open mind and heart, avoid souvenirs and explore rather than relax [34].

- (2)

- The second interpretation, based on recent tourism industry events, is connected to the overcrowding and overtourism phenomena. Martin, Martinez and Fernandez [35] speak about new situations of tourism rejection in traditionally tourism-dependent environments. Hughes [26] connects anti-tourism with consequences of mass tourism and theanti-tourism industry mobilization under the motto, ‘Tourists go home’. Thus, anti-tourism from the perspective of local residents starts after the visitor congestion point is reached. The total residents’ satisfaction with the presence of tourism turns into dissatisfaction and irritation, and residents react by opposing tourism’s development, projects and presence. This refers to a mobilized or organized movement of irritated destination residents against the development of tourism. Similarly, the definition of anti-tourism in its new meaning can also be applied from the perspective of visitors. Anti-tourism from the perspective of visitors starts after the visitors’ congestion point is reached: the overall visitors’ satisfaction with their destination experience turns into dissatisfaction, and visitors react by leaving and avoiding the destination in question.

3.2. Local Residents and Visitors Overtourism Perceptions

- (1)

- With benchmarking of corresponding sustainable tourism indicators. The European Tourism Indicator System (ETIS) [37] offers a set of such indicators that helps destinations to measure and benchmark the economic, sociocultural and environmental sustainability of a destination. The main recent studies on overtourism, already mentioned, propose their own (similar) diagnostic overtourism indicators [12,21,23,30] and overcrowding diagnostic with so-called ‘heatmaps’ [22];

- (2)

- Another approach, as already argued in this paper and derived from the sustainability orientation towards the life quality of locals, is to monitor the social capacity of tourism through stakeholders’ perceptions of impacts.

3.3. Managing Overtourism Risk

- (1)

- Impacts on the economic field are addressed in the [22] chapter ‘Overloaded Infrastructure’. Given that the infrastructure used by tourists is shared with essential non-tourism activities, such as commerce, health and transport, visitors add to infrastructure consumption and pressure that result in external effects and damage to visitors and local residents and business and businesses. The consumption of water and production of waste by visitors add to the local consumption and pollution.

- (2)

- Socio-cultural field impacts, as presented in the SRT model, are addressed in the [22] chapter ‘Threats to Culture and Heritage’. Overcrowding can threaten a destination’s spiritual and physical integrity, and crowds can make security more difficult and damage sites, including through vandalism.

- (3)

- Impacts on nature are addressed in the [22] chapter ‘Damage to Nature’. Visitors add to the overuse of natural resources, such as water and forests, waste pollution, and harm to flora and fauna.

- (4)

- Impacts on stakeholders (see Figure 1) are addressed in the [22] chapter ‘Alienated Local Residents’. Local residents complain about negative tourism impacts, such as rising rents, displacement of locals, noise, displacement of local retail, and changing neighborhood character and leakages of economic tourism benefits.

- (5)

- Impacts on visitors are addressed in the [22] chapter ‘Degraded Tourist Experience’. In many destinations, the tourist experience itself is deteriorating due to the queues, crowding, and annoyance due to overcrowding and increasing dissatisfaction with the tourist experience.

- (1)

- (2)

- In the second case, the overtourism risk is managed by managing the satisfaction of local residents and/or visitors. Here, understanding which factors have the potential to mitigate the negative perception of local residents or visitors of their tourism experience can additionally inform a destination tactic aimed at reducing the risk of overcrowding.

4. Overtourism Risk Assessment Research Construct

4.1. Overtourism Impacts Monitoring Model

4.2. Overtourism Risk Research Questions

5. Destination Ljubljana

6. Methodology and Data

7. Results and Discussion on Monitoring Overtourism in Ljubljana

7.1. Factors and Variables of Overtourism Risk

7.2. Relationships among Overtourism Risk Factors

7.3. The Mediating Power of Cooperation

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dioko, L.A.N. The problem of rapid tourism growth: An overview of the strategic question. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, W. First Venice and Barcelona: Now anti-tourism marches spread across Europe. The Guardian. 10 August 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2017/aug/10/anti-tourism-marches-spread-across-europe-venice-barcelona (accessed on 17 January 2019).

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valicon. Residents’ Attitudes Towards Tourism in Ljubljana; Report, based on research TLJ104; Tourism Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic, T. Sustainable-responsible tourism discourse–Towards ‘responsustable’ tourism. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111(Part B), 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G. Tourism, Blessing or Blight? Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, G. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants, methodology and research inferences: The impact of tourism. In Proceedings of the Travel Research Association’s Sixth Annual Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 September 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr./Le Géographe Canadien 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Tourism’s impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by Its residents. J. Travel Res. 1978, 16, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F.; Lime, D.W. Tourism carrying capacity: Tempting fantasy or useful reality? J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; Cabi Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organisation). Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations: A Guidebook; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H. Taking Responsibility for Tourism; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP; WTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable; United Nations Environment Programme, World Tourism Organization: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yasarata, M.; Altinay, L.; Burns, P.; Okumus, F. Politics and sustainable tourism development–can they co-exist? Voices from North Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Perdue, R.R.; Long, P. Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.R.; Long, P.T.; Allen, L. Resident support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalič, T. Antitourism: A reaction to the failure or promotion for more sustainable and responsible tourism. In Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Association (TTRA) European Chapter Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 25–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R. Foreword: The coming perils of overtourism. In Icelands and Trails of 21st Century Overtourism. A Deep Dive into Destinations; Rafat, A., Clampet, J., Eds.; Skift: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://skift.com/iceland-tourism/ (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organisation). Overtourism: Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth Beyond Perceptions; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WTTC & McKinsey & Company (Producer). Coping with Success: Managing Overcrowding in Tourism Destinations. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/priorities/sustainable-growth/destination-stewardship/ (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Postma, A.; Papp, B.; Koens, K. Visitor Pressure and Events in an Urban Setting. Understanding and Managing Visitor Pressure in Seven European Urban Tourism Destinations; Centre of Expertise Leisure, Tourism & Hospitality CELTH: Breda, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, M. Tourism Research Information Network Correspondence; TRINET: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, N. ‘Tourists go home’: Anti-tourism industry protest in Barcelona. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2018, 17, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, W. Wish you weren’t here: How the tourist boom–and selfies–are threatening Britain’s beauty spots. The Guardian. 16 August 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2018/aug/16/wish-you-werent-here-how-the-tourist-boom-and-selfies-are-threatening-britains-beauty-spots (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Dickinson, G. Overtourism. New Word Suggestion. Collins Dictionary. Available online: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/submission/19794/Overtourism (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Responsible Tourism. Overtourism. Available online: http://responsibletourismpartnership.org/overtourism/ (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Research for TRAN Committee—Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buzard, J. The Beaten Track: European Tourism, Literature, and the Ways to ‘Culture’, 1800–1918; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.L.; Auyong, J. Remarks on tourism terminologies: Anti-tourism, mass tourism, and alternative tourism. In Proceedings of the 1996 World Congress on Coastal and Marine Tourism: Experiences in Management and Development; Washington Sea Grant Program and the School of Marine Affairs, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA; Oregon Sea Grant College Program, Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 1998; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, P. Conceptualizing urban exploration as beyond tourism and as anti-tourism. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. (AHTR) 2015, 3, 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- McWha, M.R.; Frost, W.; Laing, J.; Best, G. Writing for the anti-tourist? Imagining the contemporary travel magazine reader as an authentic experience seeker. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, J.M.; Guaita Martínez, J.G.; Salinas Fernández, J.A. An analysis of the factors behind the citizen’s attitude of rejection towards tourism in a context of overtourism and economic dependence on this activity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmnuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. The European Tourism Indicator System: ETIS toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Muler González, V.; Galí Espelt, N.; Coromina Soler, L. Overtourism: Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity—Case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Jurado, E.; Tejada Tejada, M.; Almeida García, F.; Cabello González, J.; Cortés Macías, R.; Delgado Peña, J.; Fernández Gutiérrez, F.; Gutiérrez Fernández, G.; Luque Gallego, M.; Málvarez García, G.; et al. Carrying capacity assessment for tourist destinations: Methodology for the creation of synthetic indicators applied in a coastal area. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Sousa, A. The Problems of Tourist Sustainability in Cultural Cities: Socio-Political Perceptions and Interests Management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, L. Residents’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in a Historical-Cultural Village: Influence of Perceived Impacts, Sense of Place and Tourism Development Potential. Sustainability 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SORS. Data. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Available online: https://pxweb.stat.si/pxweb/Dialog/varval.asp?ma=2164521S&ti=&path=../Database/Ekonomsko/21_gostinstvo_turizem/01_nastanitev/02_21645_nastanitev_letno/&lang=2 (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Van de Ven, A.H. Engaged Scholarship: A Guide for Organizational and Social Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, M.; Lecavalier, L. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in developmental disability psychological research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Arnett, K.P. Exploring the factors associated with web site success in the context of electronic commerce. Inf. Manag. 2000, 38, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Ljubljana. Database on TLJ104; The Ljubljana Tourism Public Institute: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sustainability Impacts and Enablers | Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECONOMIC IMPACT | Hospitality tourism business | 1.000 | |||||

| Tourism superstructure | 0.514 | 1.000 | |||||

| SOCIOCULTURAL IMPACT | Destination life quality | 0.261 | 0.335 | 1.000 | |||

| Community benefits | 0.397 | 0.543 | 0.378 | 1.000 | |||

| ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT | Pollution and traffic | 0.293 | 0.311 | 0.518 | 0.240 | 1.000 | |

| STEKEHOLDER COOPERATION ENABLER | Cooperation | 0.447 | 0.508 | 0.453 | 0.601 | 0.204 | 1.000 |

| No. | Sustainability Impacts and Enablers | Loading/Cronbach’s Alpha | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | t | Sig. (2-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECONOMIC IMPACTS | |||||||

| 1 | Hospitality tourism business | 0.794 | 3.61 | 0.782 | 0.034 | 17.814 | 0.000 |

| 1.1 | There is high-quality service in restaurants and cafes in the city center. | 0.933 | 3.67 | 0.956 | 0.042 | 16.041 | 0.000 |

| 1.2 | Employees in restaurants and cafes in the city center are friendly. | 0.913 | 3.85 | 0.903 | 0.039 | 21.578 | 0.000 |

| 1.3 | The offer of local food in restaurants and cafes in Ljubljana is good. | 0.417 | 3.75 | 1.031 | 0.045 | 16.697 | 0.000 |

| 1.4 | Prices in restaurants and cafes in the city center are appropriate. | 0.397 | 3.16 | 1.079 | 0.047 | 3.402 | 0.001 |

| 2 | Tourism superstructure | 0.668 | 3.98 | 0.845 | 0.037 | 26.409 | 0.000 |

| 2.1 | Shopping, restaurants and entertainment options are better because of tourism. | 0.756 | 3.88 | 1.014 | 0.044 | 19.810 | 0.000 |

| 2.2 | The increase in the number of tourists in the community helps the development of the local economy. | 0.535 | 4.07 | 0.935 | 0.041 | 26.257 | 0.000 |

| SOCIOCULTURAL IMPACTS | |||||||

| 3 | Destination life quality | 0.794 | 3.84 | 0.919 | 0.040 | −20.848 | 0.000 |

| 3.1 | Residents in the city center feel penned in (reverse-coded). | 0.806 | 3.39 | 1.221 | 0.053 | −7.225 | 0.000 |

| 3.2 | The number of tourists in Ljubljana should be limited (reverse-coded). | 0.663 | 3.91 | 1.221 | 0.053 | −17.099 | 0.000 |

| 3.3 | Living in a tourist place is unpleasant (reverse-coded). | 0.656 | 3.65 | 1.184 | 0.052 | −12.622 | 0.000 |

| 3.4 | Due to tourism, I would like to move out of Ljubljana (reverse-coded). | 0.609 | 4.4 | 1.038 | 0.045 | −30.809 | 0.000 |

| 4 | Community benefits | 0.767 | 4.13 | 0.793 | 0.035 | 32.603 | 0.000 |

| 4.1 | The community benefits from tourism and tourists who visit us. | 0.716 | 4.18 | 0.898 | 0.039 | 30.112 | 0.000 |

| 4.2 | The development of tourism contributes to the development of Ljubljana. | 0.716 | 4.42 | 0.801 | 0.035 | 40.617 | 0.000 |

| 4.3 | The development of tourism contributes to a better quality of life in Ljubljana. | 0.645 | 3.78 | 1.147 | 0.050 | 15.647 | 0.000 |

| ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS | |||||||

| 6 | Pollution and traffic (reverse-coded) | 0.745 | 3.52 | 1.069 | 0.047 | −11.174 | 0.000 |

| 6.1 | Tourism in Ljubljana causes air pollution (reverse-coded). | 0.859 | 3.64 | 1.164 | 0.051 | −12.531 | 0.000 |

| 6.2 | The development of tourism increases traffic problems in Ljubljana (reverse-coded). | 0.642 | 3.41 | 1.231 | 0.054 | −7.559 | 0.000 |

| STAKEHOLDER COOPERATION ENABLERS | |||||||

| 5 | Cooperation | 0.728 | 2.96 | 0.998 | 0.044 | −0.963 | 0.336 |

| 5.1 | Overall, I am very pleased with the inclusion and influence of residents in the planning and development of tourism. | 0.801 | 3.06 | 1.168 | 0.051 | 1.271 | 0.204 |

| 5.2 | When planning tourism in Ljubljana, the quality of life of residents is taken into account. | 0.694 | 3.08 | 1.118 | 0.049 | 1.681 | 0.093 |

| 5.3 | I benefit from tourism and tourists who visit us. | 0.506 | 2.73 | 1.413 | 0.062 | −4.422 | 0.000 |

| χ2 | p | df | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 365.855 | 0.000 | 127 | 2.881 | 0.933 | 0.933 | 0.060 | 0.0537 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuščer, K.; Mihalič, T. Residents’ Attitudes towards Overtourism from the Perspective of Tourism Impacts and Cooperation—The Case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061823

Kuščer K, Mihalič T. Residents’ Attitudes towards Overtourism from the Perspective of Tourism Impacts and Cooperation—The Case of Ljubljana. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061823

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuščer, Kir, and Tanja Mihalič. 2019. "Residents’ Attitudes towards Overtourism from the Perspective of Tourism Impacts and Cooperation—The Case of Ljubljana" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061823

APA StyleKuščer, K., & Mihalič, T. (2019). Residents’ Attitudes towards Overtourism from the Perspective of Tourism Impacts and Cooperation—The Case of Ljubljana. Sustainability, 11(6), 1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061823