Abstract

What CEO attributes can improve corporate sustainability? In this regard, what do superstar CEOs, e.g., Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates, have in common? Also, did the personalities of Jeffrey Skilling and Kenneth Lay contribute to the crack in the US Enron Corporation early in this century? Why, as far as presidential elections are concerned, are some countries, more than others, more likely to vote for seemingly narcissistic politicians? In our practice-oriented review article, we aim to contribute to shedding new light on the challenging evidence continuously evolving around CEOs, in general, and around their effect on corporate sustainability, in particular. Two distinctive features represent the main “so-what” value of our work. First, each of the CEO attributes which we sequentially focus on (i.e., power, personality, profiles, and effect) is, at the beginning, not only separately considered but also associated with many recent examples from business life and from the “CEO world” at an international level. Second, from our analysis, we then derive a conceptual framework which, combining all these attributes into a unique body of knowledge, could be used as a potential starting point for future investigations in this challenging research area regarding the CEO/sustainability relationship. In this regard, we believe understanding how all the analysed attributes coevolve will represent a pivotal question to address if we want to enhance the scientific and practical understanding of CEO (sustainable) behaviour.

1. Introduction

What CEO attributes can improve corporate sustainability? In this regard, what features do superstar Chief Executive Officers (CEOs), e.g., Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates, have in common? Also, did the personalities of Jeffrey Skilling and Kenneth Lay contribute to the crack in the US Enron Corporation early in this century? Why, as far as presidential elections are concerned, are some countries, more than others, more likely to vote for seemingly narcissistic politicians? Our practice-oriented review article aims to contribute to shedding new light on the challenging evidence continuously evolving around CEOs, in general, and around their effect on corporate sustainability, in particular. In this regard, we, thus, follow a recent stream of research which attempts to link the sustainability of corporate governance and strategic management with the personal attributes of corporate executives.

In the 1980s, addressing the question of why important business magazines focus on strategic leaders’ sociodemographic characteristics, Hambrick and Mason conjecture the seminal Upper Echelons Theory (UET), in which “organizations become reflections of their top managers” ([1], p. 193). Influenced by Simon’s bounded rationality [2], they rely on two connected assumptions: (i) Organizational top decision makers decide on the basis of how they personally interpret their strategic contexts; (ii) the way these top decision makers interpret reality stems from their cognition, experience, beliefs, and personality.

On this premise, Hambrick and Mason propose their theory through two additional, intertwined beliefs: first, they argue that studying all the organizational top decision makers, rather than only one, e.g., the CEO, or just a few can more accurately explain the organization’s strategic leadership. The key rationale here is that organizational governance is a complex activity in which not only the personal characteristics of the top decision makers individually but also their accumulated effect count. Second, they state that the sociodemographic features of top decision makers can represent good—although physiologically incomplete—proxies of their cognitive values. The sociodemographic variables which Hambrick and Mason originally introduce as proxies are (i) age, (ii) functional background, (iii) other career experiences, (iv) education, (v) socioeconomic background, (vi) financial position, and (vii) group characteristics. They then build some theoretical propositions about the potential relationship between the variables above, behavioural strategy, and executive leadership; for example, they conjecture that organizations with young top decision makers, on average, can set more risk-inclined than risk-averse strategic decisions, that organizations with homogeneous rather than heterogeneous dominant coalitions are quicker at decision-making, or that product innovation is facilitated when the years of education of the dominant coalitions are many.

This explained, in partial contrast to the seminal 1984 UET model, the study of CEOs rather than entire dominant coalitions as specific units of analysis has progressively emerged in parallel with others as a per se research stream within UET [3,4,5]. In particular, to date, research has specifically focused on a number of dimensions regarding CEOs’ central roles in firms [6,7,8].

Taking all this into account, two distinctive features represent the main “so-what” value of our work and also constitute its main structure. First, each of the CEO attributes which we sequentially focus on (i.e., power, personality, profiles, and effect) is, at the beginning, not only separately considered but also associated with many recent examples from the business life and from the “CEO world” at an international level. Second, from our analysis, we then derive a conceptual framework which, combining all these attributes into a unique body of knowledge, could be used as a potential starting point for future investigations in this challenging research area regarding the CEO/sustainability relationship. The limitations and implications, then, conclude our contribution. As for the former, the potential roles of endogeneity and corporate governance mechanisms are given particular attention. As for the latter, we believe understanding how all the analysed attributes coevolve will represent a pivotal question to address if we want to enhance the scientific and practical understanding of CEO behaviour towards (sustainable) corporate performance.

2. CEO Power

As anticipated, to date, CEOs seem particularly appealing as a per se unit of analysis of the firms’ dynamics, especially because of their supposed power in influencing the firms’ strategies and related organizational performance. This aspect is studied under the label of “managerial discretion” [9,10], i.e., the real degree of possibility for a dominant coalition or, for some of its members (with its CEO in primis), to effectively act without (or with limited) constraints [11].

Over time, different measures of CEO power have been implemented. Some corporate governance scholars, for example, have identified CEO power as the compensation gap between a CEO and the second most important person in a firm, i.e., the highest-paid non-CEO executive [12], while others have adopted CEO pay slice, CEO tenure, or CEO duality for power measurement [13]. UET scholars, instead, have identified three clusters of variables to be contemporaneously considered when investigating CEO power: CEO sociodemographic features, board dynamics, and contextual variables. Regarding the first cluster, Finkelstein [14] and Bigley and Wiersema [15] define that (i) the number of titles, (ii) compensation, (iii) stock ownership, (iv) family link to founders, (v) functional expertise, (vi) elite education, and (vii) number of outside board memberships, together, all affect the grade of CEO power.

In this regard, for example, stock ownership, together with personality features, is a pivotal variable at the basis that made Mark Zuckerberg, the founder/CEO of the Facebook social media platform, autonomously decide to buy Instagram (a social media app based on photo sharing). As reported by The Wall Street Journal [16], on the morning of 8 April 2012, Zuckerberg notified his board members that he had privately negotiated the purchase with the Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom and that the announcement would have been given the next day; specifically, “by the time Facebook’s board was brought in, the deal was all but done”. In this case, the board, according to one person familiar with the matter, “was told, not consulted”.

Having reported the anecdotal evidence above and regarding the sociodemographic variables, Magnusson and Boggs [17] highlight that CEO international tenure also influences CEO power; what emerges from their study is that the greater a candidate’s international tenure, the greater the chance of becoming a CEO; however, according to Tang et al. [18], high-tenured CEOs can become so reliable that they can induce executives to assume risk-oriented strategic behaviours. From this, an intertwined relationship between CEO features and board dynamics also emerges as an influencing mechanism of CEO managerial discretion.

About board dynamics per se, in a study of a sample of firms from eight manufacturing sectors of the Pakistani economy, it is found that CEO power positively influences the relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and corporate performance [19]. However, the results are also contrasting. In fact, recent studies demonstrate how the presence of large boards, independent board members, as well as numerous board meetings and increasing incentives for the executives have the effect of significantly improving both the probability and quality of sustainability reporting; this ultimately has a positive influence on the firms’ market value [20]. This apparently means that the greater the inclusiveness of other executives in strategic decisions, with the effect of decreasing CEO power, the greater the positive effect on sustainability practices. In line with this, some scholars [13] recently found that CEO power was negatively associated with the firm’s engagement in CSR and with the level of CSR activities in the firm, despite these activities increasing the corporate value. An explanation of this result can be found in the lack of explicit linkage between the environmental performance and executive contracts; in fact, as found by Cordeiro and Sarkis [21], only when CEO compensation levels were linked to environmental performance was there a positive engagement of the executives with CSR activities.

Quigley and Hambrick [22] suggest that, during CEO successions, power dynamics involve three important parties: the board, the incumbent CEO, and the successor CEO. Within this process, the prior CEO restricts the discretion of the new CEO if the former is still a board member. Horner and Valenti [23] specifically consider the balance of power among these parties in CEO successions, witnessing the presence of CEO duality, and find that incoming CEOs (with prior chair experience) and outgoing CEOs (with high CEO tenure) are those who possess the maximum power in this process. Herrmann and Datta [24] analyse the relationship between CEO succession and foreign market entry-mode of 126 US firms and support their hypothesis that CEOs with great experience, throughput backgrounds, great legitimacy, and international tenure prefer full-control entry-modes.

It is expectable that CEOs are able to influence not only their succession but also the appointment of board members, which can sometimes lead to a “similar-to-me” effect in order to enhance CEO power. For example, Bloomberg [25] reports that Tesla, the innovative electric-car maker, “is searching for independent directors, as an influential group of investors pressures the electric-car maker’s board to add two members who don’t have ties to Elon Musk”. This claim is considered necessary because over 80% of the board members have personal/professional connections with the CEO, thus presumably influencing the concentration of decision-making power and the occurrence of the so-called groupthink bias [26,27].

Being powerful can be harmful when competition is intense; as found by Han et al. [28], firms acting in industries with large managerial discretion (i.e., where the strategic decision-making process is concentrated in CEO hands) perform worse than firms where power is distributed or when CEOs are advised by independent board members. Therefore, the munificence of the environment (at the industry or country level) is the third (and last) explanatory variable of CEO power and the firms’ performances. Focusing on 830 CEOs of US listed companies in 44 different industries over a 20-year period, Hambrick and Quigley [29] studied the CEO effect in industries with different grades of discretion (i.e., measured as environmental munificence). Through this specification, they composed a new variable, “CEO in Context” (CiC), which is in contrast to customized techniques because it includes variables not related to CEOs for investigating CEO power. Thanks to this new inclusive measure, contrary to prior studies in which CEOs account for 10–20%, they found that CEOs account for 30–40% of company performance. Similarly, Datta et al. [30] found that industry discretion mediated CEO openness to changing the corporate strategic direction; in practice, industries with a low discretion reduced the power of CEOs to act on their firms’ strategies. On the same issue, Li and Tang [31] found support for the hypothesis that market munificence and complexity gave CEOs more discretion and, consequently, they behaved more riskily. Similarly, two empirical studies by Crossland and Hambrick [32,33] demonstrated how national-level factors affected executive discretion, reaching the important conclusion that CEO influence varied by country (because of the different macroeconomic conditions).

3. CEO Personality

Scholars and practitioners currently consider the exploration of specific personality traits of CEOs, e.g., narcissism, hubris, or overconfidence, as a particularly promising area both to understand how the dynamics internal to dominant coalitions effectively work and to capture their overall impact on organizations and their sustainability. For example, recently Park and Chung [34] empirically demonstrated that firms with overconfident CEOs tended to overinvest because they were overly optimistic about investment opportunities and were more likely trying to catch them, highlighting that this feature was not beneficial for firms’ sustainabilities.

On this premise, a major catalyst in this research stream has been the pioneering work by Chatterjee and Hambrick [35], who found a directly proportional relationship between the strategic dynamism of a sample of American firms and the narcissism of their CEOs. This work is also interesting for the operationalization of narcissism, evaluated through non-psychometrically validated measurements, such as the CEO’s picture in the company’s annual report, the CEO preeminence in the company’s press release, or even the CEO’s usage of the singular personal pronoun in interviews. This analytical approach seems to be the most followed in recent literature on this topic and has led to relevant contributions, such as the positive relationship with the CEO’s attention to a discontinued technology [36], which can be beneficial for industries with a high managerial discretion and recurrent technology shifts. In this regard, Zhu and Chen [37] also demonstrated how narcissistic CEOs, to prove their superiority, usually adopted evolutionary paths which were contrary to the prior experience of their directors. This also limited, de facto, their directors’ action.

However, when reaching extreme levels, CEO narcissism has sometimes been considered as a threat from which organizations should escape to avoid dramatic consequences [38,39], and it has not been considered as a sustainable practice for firms, especially when associated with high tenure. We can consider, for example, as reported by USA Today [40], the clamor caused by a letter sent by four eminent American psychiatrists to Congress members, in which they showed fear for the current US President’s mental health, with particular reference to his excessive narcissism. These professionals, in fact, alerted the media about the potentially disastrous effects of a statement in response to a North Korean missile launch in August 2017; in this statement, the US President said that the Korean move would be addressed with “fire and fury like the world has never seen”. These eminent practitioners, led by the forensic psychiatrist Bandy Lee, declared: “We now find ourselves in a clear and present danger, especially concerning North Korea and the president’s command of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.”

However, psychiatrist Michael Welner correctly said that: “Any assessment of dangerousness of a President would need to have adequate access to personal and intimate communication, his choices and his vision, evidence historically for one’s dangerousness, and the circumstances of how that manifested itself, and relate to the context of the evaluation, in this case in the context of presidential power.” Incidentally, this statement also seems in line with recent empirical studies highlighting that CEOs’ narcissism has a negative relationship on ethics, social responsibility, and CSR activities.

Taking all this into account, because of the criticisms moved to the secondary data used within Chatterjee and Hambrick’s [35] measure of narcissism, scholars have enhanced the measurements in order to have a more comprehensive evaluation of CEO narcissism. For example, while demonstrating the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and unethical behaviour (i.e., fraud), Rijsenbilt and Commandeur [41] included additional proxies, e.g., CEO duality and compensation, exposure (in terms of public acknowledgement), number of lines used in biography, and perquisites (e.g., company aircraft use).

Having considered narcissism, a second personality trait increasingly capturing attention is CEO hubris, considered to be one of the most important aspects affecting CEO strategic choices and judgement. Hubris is a complex construct deriving from two kinds of antecedents [42]: personal dispositions (e.g., narcissism and educational background) and external stimuli (e.g., firms’ recent media praise). These antecedents affect CEO hubris; some symptoms are CEO overestimation of their own abilities, performance and/or probability of success, and CEO unbridled intuition.

Hayward and Hambrick [43] are the first to study CEO hubris, measuring this construct through proxies such as recent media praise and organizational performance, and CEO–executives’ pay differential. They find that CEO hubris is positively associated with acquisition overpayment; more recently, besides this negative effect, hubris has also been demonstrated to lead to fast decision processes and efficient communication [42]. In contrast, through a longitudinal dataset of S&P 1500 index firms for the period 2001–2010, Tang et al. [44] found that there was a significant negative relationship between CEO hubris and corporate engagement in CSR activities; however, when firms depended on stakeholders for resources and the external market became more uncertain and competitive, this relationship was seemingly weakened.

All this explained, Hiller and Hambrick [45] have proposed following a new, psychologically validated construct (i.e., the Core Self-Evaluation (CSE) index) to reconcile all the intertwined personality aspects mentioned above. According to them, CEOs should show a CSE index higher than the general population, which would affect their strategic choices. Notwithstanding this conceptual, methodological milestone, other scholars have deviated from this suggestion over time, such as Li and Tang [31], who assessed executive hubris through a comparison of CEO impressions of their firms’ financial performance and the objective situation. In their study of the relationship between CEO hubris, firm risk taking, and managerial discretion, they discovered that CEO hubris was strongly positively related to firm risk taking when managerial discretion was high; however, when considering opposite cultures (i.e., American and Chinese), Li and Tang [46] found that hubris was widely affected by the beliefs and values of the country in which the executives were embedded.

This link between managerial discretion and CEO hubris can also be found in the statements of Sepp Blatter—the president of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) for over 17 years—when he won the FIFA presidential election in May, 2015; in particular, as reported by The Telegraph [47], he declared: “At the end of my term of office, I will be able to hand over a solid FIFA, a FIFA that will have emerged from the storm.” However, playing on his opponent’s inexperience, he said: “You know me already. I don’t need to introduce myself to you. You know who you’re dealing with and I also know I can count on you. What football needs right now is a strong leader, an experienced leader.” However, a few days after the renewal of the term, he stepped down from his position because of a corruption scandal involving FIFA and himself.

Notwithstanding this interest in narcissism, overconfidence, and hubris, a consultancy firm, which spent 10 years creating a database called the CEO Genome Project [48], analysed the personality traits of 2000 CEOs and collected information on the performance of 212 of them. The results, in contrast to the above-reported literature, showed that, despite charismatic and extroverted CEOs being the most desired to be hired for companies, introverted CEOs seemed to be better performers. Moreover, four main traits emerged as features in top performing CEOs: reaching out to stakeholders, being highly adaptable to change, being reliable and predictable, and making fast decisions with conviction. From this, a strong connection between personality elements and CEO performance emerges as pivotal.

4. CEO Profiles

To date, another major call for research is in the identification of CEO profiles worldwide, about which, especially outside US boundaries, we know little, for example, in terms of the industrial homogeneity or economic systems which the culture of is less individualistic than that of the US [49]. For example, one of these avenues looks at the effect of CEO sociodemographic features on CSR performance. In this regard, focusing on the CSR ranking of 392 firms, Huang [50] found that high tenured CEOs with a Master’s in Business Administration positively affected corporate CSR performance and that this result was even more significant if these CEOs were women. In this last vein, Loh and Guyen [51] found that the presence of women in top positions of corporate governance had an indirect effect on financial performance, while others found that female CEOs significantly promoted both incremental and radical innovation behaviours, together with having a positive effect on CSR disclosure and environmental investment [52]; however, the latter effect was context-dependent. From that, studying if/how the homogeneity of CEO profiles has been coevolving with the culture of the economic systems also appears worth mentioning [49,53,54].

Therefore, over a 15-year time span, Crossland and Hambrick [32] compared the relationship between CEOs and performance in American, Japanese, and German firms; they found that only the performance of American firms could be mainly associated with their CEOs’ performance rather than with the institutional, cultural, industrial, and even organizational context in which these CEOs operated. Conversely, the CEOs of Japanese firms appeared to be almost interchangeable. Crossland and Hambrick explained this difference with the fact that, good or bad, the degree of CEO managerial discretion was the highest in the US and the lowest in Japan. Subsequently, Crossland and Hambrick [33] empirically linked the institutions and firm performance via managerial discretion at a national level, a study greatly expanding the theory of managerial discretion.

The results above found evidence also in the practice of business, as reported by The Japan Times [55]. In particular, Atsushi Saito, prior CEO of the Japan Exchange Group, declared: “Right now there isn’t much attraction to being a CEO” because of the low salary (compared to the US CEOs), which are usually fixed and not linked to the firms’ performances. Because of that, Saito stated, “Japanese CEOs are not pushed to take risk-taking decisions, also because after their retirement former CEOs are asked to be advisors of their prior companies.” However, this problem is obviously linked to the cultural differences among Western and Eastern countries; Saito said: “If someone like Steve Jobs was in Japan, how would the Japanese treat him? If he had joined a large Japanese company, he probably would have been fired immediately.”

The cultural clash between CEOs and their firms and/or country culture is more than a minor problem; it can lead to the CEO being fired or to a corporate crisis [56]. In 2016, for example, the Swedish bank Handelsbanken removed its CEO, Frank Vang-Jensen, following his failure to accept the bank’s traditional way of working, which was focused on decentralising responsibilities to branches’ senior managers [57]. In particular, on the basis of his prior experience in the UK context, the later-fired CEO tried to centralise many responsibilities and decisions. However, even if his performance was positive, the board of directors suggested to shareholders there should be a CEO turnaround due to this misalignment.

To date UET scholars have started to explore how CEOs’ past or present activities outside their boards, as well as personal beliefs, can influence their strategic choices [58]. In this regard, it is interesting that, in 2015, 15 Fortune 500 CEOs “got their start in the military” [59]. For example, this is the case of Alex Gorsky, the CEO of Johnson & Johnson and past CEO of IBM, under whose leadership the corporate net profit rose by 18% in 2014 on the basis of a 4.2% increase in sales [60]; Robert A. McDonald, the past CEO of Procter & Gamble, under whose guidance the corporate stock value was up 54% [61]; and Daniel Akerson, the past CEO of General Motors, under whose governance the corporation, in 2011, earned a record USD 7.6 billion in profit on the basis of USD 150.3 billion in sales [62].

Also, personal beliefs and orientations, as already introduced, seem to be variables that, in some way, influence CEO decision-making activities. For example, as reported by Fortune [63], Indra Nooyi, CEO of PepsiCo, declared: “There are times when the stress is so incredible between office and home […] Then you close your eyes and think about a temple like Tirupati, and suddenly you feel ‘Hey—I can take on the world’. Hinduism floats around you and makes you feel somehow invincible.” Donnie Smith, CEO of Tyson Food, is a Christian Baptist who teaches the Bible on Sundays and tries to live according to the Bible. In particular, he declared: “My faith influences how I think, what I do, what I say […] There are a lot of great biblical principles that are fundamental to operating a good business. Being fair and telling the truth are biblical principles.” [64].

In summary, CEOs appear animated by their beliefs/spirituality while acting inside and outside the boardroom. Thus, considering whether CEOs have some particular beliefs or not can produce important insights on the consistency of their actions and decisions, thus ensuring the sustainability of their performance over time, which has become a pivotal variable in assessing their results.

5. CEO Effect

From all that we have explained in the preceding sections, CEOs do influence the corporate performance through their power, personality traits, or profile adaptation to the environment. Crossland and Hambrick [33] identify that the effect of US CEOs seems to be generally higher than that of their Eastern counterparts, mainly because of the cultural differences that drive them, respectively, to high and low CEO managerial discretion; however, other important studies have produced conflicting results. Whiters and Fitza [65] highlighted how the CEO influence on business performance seems to be greater in the lower growth sectors where managerial discretion had previously been conceived as minor [32] because business leaders are considered to have a key role, given the context of the general scarcity of resources.

Recently, and mainly through longitudinal analyses, scholars have been trying to investigate how much the CEO effect, discussed above, is. The first contribution of the scientific literature in this direction is Lieberson and O’Connor’s [66] seminal work, which isolates the CEO effect on business results, detecting an incidence of about 15%. However, later studies have not led to convergent results. On the one hand, a first series of further research has identified that company performance is mainly determined by the competitive and macroeconomic environment in which companies are embedded [67,68]. This major effect of the environment has been justified through highlighting the rigidity of corporate investments, the strategic preference for maintaining the status quo, and the pressure suffered by business leaders from governmental measures that limit their power to act. On the other hand, another series of further studies has shown the greater causal weight of CEOs with respect to the environment in determining business performance. For example, Jahanshahi and Brem [69] found that CEOs able to promote behavioural integration in their boards could positively impact innovativeness and sustainability-oriented actions. The general effect of CEOs with respect to the environment seems to be more and more important over time. In particular, from a 1950–2009 panel study, Quigley and Hambrick [70] found a robust increase in the proportion of variance in performance attributable to CEOs of US public corporations.

Analysing the various empirical results evolving (Table 1), it might emerge that the weight of CEOs’ influences on company performance has been identified, on average, as higher than that exercised by the sector and the macroeconomic environment in which companies operate; however, the former seems to be lower than the effect determined by the resources and competences of the company these executives are in charge of.

Table 1.

The CEO effect over time: An analysis of the most representative literature.

It is important to underline that many studies, especially the most recent, have tried to identify whether the greatest influence of CEOs on business performance somehow depends on the specific economic sectors and on the institutional context in which they operate. Crossland and Hambrick [32] and Wangrow et al. [11] showed that, among a multitude of individual and business factors, CEO power seemed to be amplified by the growth rate of the sector and by the differentiability of products. In particular, in sectors with high growth rates and/or that are characterized by a high differentiation of products, CEOs usually had great decision-making autonomy and, therefore, were associated with commensurate causality. This important evidence should also be read in light of the different institutional environments in which CEOs operate. The Harvard Business Review has been undertaking a ranking of the top performing CEOs among the S&P Global 1200 index. One of the latest rankings [80], which considers the financial performance adjusted for the munificence of the industry and of the macroeconomic environment, shows that Jeff Bezos (Amazon, Seattle, WA, USA), Huateng Ma (Tencent, Shenzhen, China), Laurence Fink (Blackrock, New York, NY, USA), and Reed Hastings (Netflix, Los Gatos, CA, USA) are the first four top performers. In other words, they should be considered as the persons that, in practice, affect their company performance the most; under their guidance, their companies increased their market capitalization by USD 442, 299, 80, and 65 billion respectively.

6. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

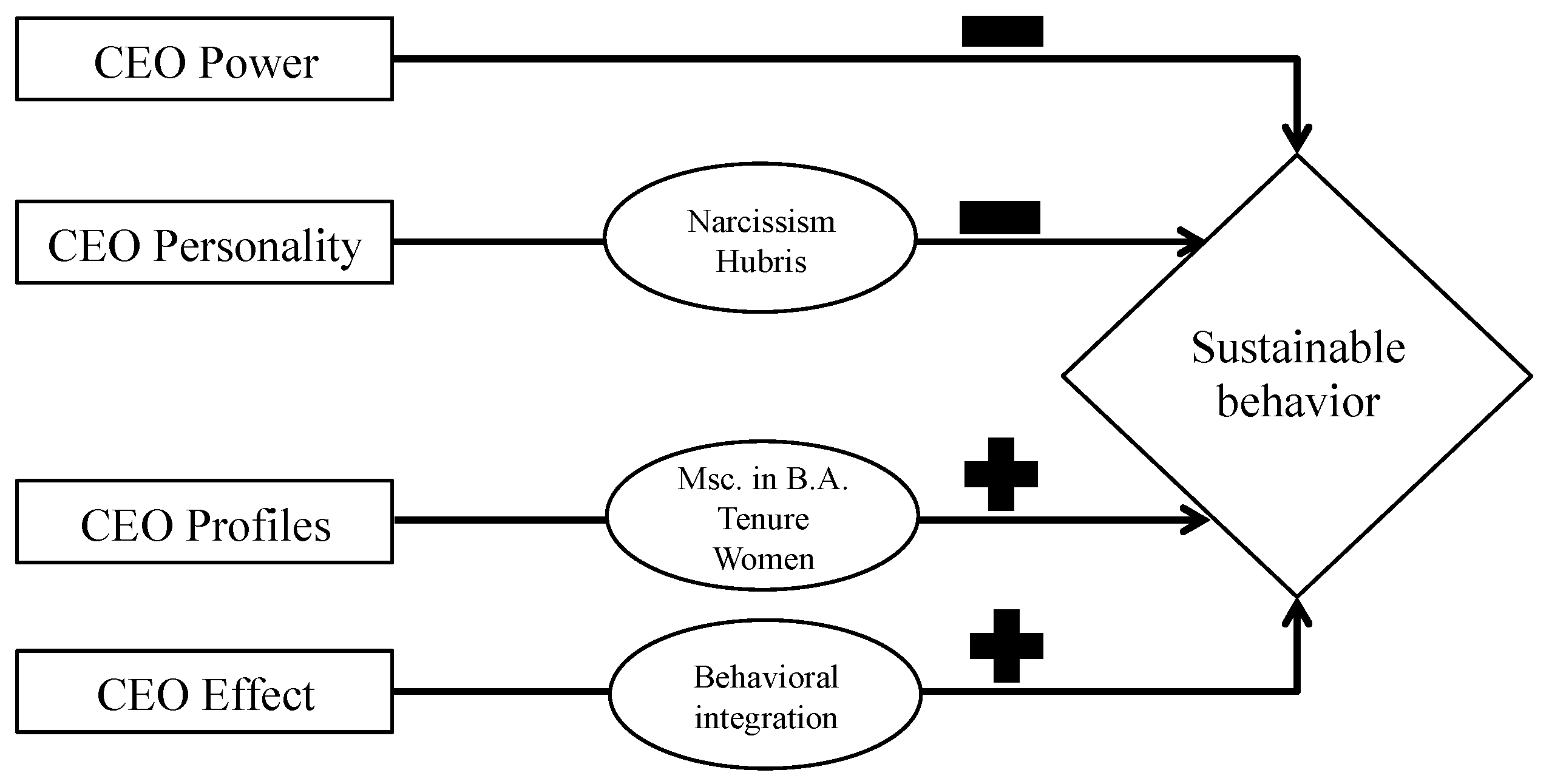

In this practice-oriented review article, we have used many recent international examples from the practice of business to find a connection between some important personal attributes of CEOs and corporate sustainability. In this regard, as Figure 1 can help explain, some interesting, although not conclusive evidence, starts to emerge. Thus, in this section, we elaborate on those issues which, among the others, seem the most challenging to be discussed.

Figure 1.

CEO attributes and corporate sustainable behaviour.

First, CEO power has been generally found to have a negative influence on the sustainable practices of firms [12,13,21,50,81]. In contrast, however, CEO power may lead to a sustainable corporate behaviour if associated with environmental expertise or if there exists an explicit linkage between environmental performance and CEO compensation in her/his contract.

As for CEO personality, narcissism and hubris, which have been found to play pivotal roles in strategic dynamism [35], fast decision processes, and efficient communication [42], represent the features that have a seemingly negative impact on CEO sustainable behaviour [44]. This result, therefore, is more in line with those studies assigning a negative influence to these two features on some aspects of CEOs’ strategic postures, such as acquisition overpayment [43] or risk taking [31].

Differently from the personality features above, some sociodemographic features seem to have a positive impact on CEO sustainable behaviour, such as having a Master of Science in Business Administration, being tenured, or being a woman [50]. About gender, for example, various studies have demonstrated that appointing a woman as a CEO can increase the chances of pursuing sustainable behaviour, such as investing in radical innovations, performing CSR disclosures, or implementing environmentally oriented decisions [52].

Last but not least, studies that have been concerned with the CEO effect/sustainability relationship are very recent; in this regard, it has been found that CEOs able to promote behavioural integration among board members could positively impact sustainability-oriented actions [69].

Second, although the CEO characteristics reported above, when individually considered, might show a causal effect on corporate sustainability, it is also important to acknowledge that, in the practice of business, these characteristics do not act in a stand-alone way; on the contrary, they are closely intertwined and influence each other. Furthermore, in this vein, some contextual factors (at the organizational, industrial, and/or institutional level) can play a pivotal role in mediating/moderating this effect. Thus, both conceptually and methodologically, a potential problem of endogeneity seems to be worthy of discussion here [82]; more specifically, a characteristic/variable not included in a study is, de facto, related to a characteristic/variable that, instead, has been included. On this basis, the excluded variable may have no effect or explanatory power, or it may act as a covariate that influences the outcome of interest.

On the issue above, the interrelationships among the most important variables considered by the UET stream of research have recently been reframed through a coevolutionary lens [4]. On this basis, corporate sustainability can also be viewed as contemporarily determined by CEO/board characteristics, environmental factors (i.e., organizational, industrial, and institutional context), and moderators (e.g., managerial discretion, distribution of power, and executive job demands). Consequently, avoiding considering one (or some) of these factors can undermine the explanatory power of studies. For example, CEO power and sociodemographic features could have a two-way causality; at the same time, however, CEO power depends on environmental factors and corporate performance, and CEO sociodemographic features emerge as prevalent in an industry according to specific environmental features (i.e., the phenomenon of the so-called “reverse causality” [82]).

To mitigate endogeneity from a methodological point of view, some scholars have focused on specific econometric techniques. Among those, in the study by Li [12], the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) for dynamic models has been found to have the most significant correction effect against endogeneity. Similarly, Antonakis et al. [83] suggested that, when facing the endogeneity problem in experiments, the researcher should plan randomized experiments so that groups of individuals in the controlled and not controlled groups were similar on each observable and unobservable characteristic. These scholars then propose 10 Commandments of Causal Analysis, in which the first is that of avoiding an omitted variable bias by including appropriate control variables.

Third, which is also strictly associated with the first and second items discussed above, some corporate governance mechanisms are also seemingly intertwined with CEO personal attributes, with the consequence of escalating the complexity in finding antecedents and/or consequences of CEO (sustainable) behaviour. For example, it is known that, in the UET literature, compensation and stock ownership have been considered as antecedents of CEO power [14,15] as well as proxies for CEO narcissism [41]. In this regard, if we consider the corporate governance literature, firms seem to use stock options and restricted stocks to CEOs to manage the optimal level of equity incentives [84]. However, the variations of CEO compensation contracts (and supposed incentives) are dependent on CEO attributes, which, in turn, are considered to be proxies for CEO human capital and risk aversion [85]. In summary, all these highlight, again, the potential endogeneity between the CEO characteristics and their compensation with possible effects also on their power.

The use of compensation mechanisms has been adapted to the specific degree of competition experienced by firms in any given industry. In particular, as found by Giroud and Mueller [86], firms in noncompetitive industries benefited more from stronger shareholders’ rights than firms in competitive industries, with the consequence of lowering executive/managerial compensations in the former. This also introduced another potential element of endogeneity between managerial discretion and corporate governance mechanisms, which has been studied by Li [87] when investigating the presence of mutual controlling mechanisms in S&P 500, S&P Midcap 400, and S&P Smallcap 600 firms from 1992 to 2006. In particular, Li found that, when the second most important corporate executive was given authority, incentive, and influence, she/he was able to monitor and constrain the potentially self-interested CEO and, thus, to increase the corporate value. However, when the compensation gap between the CEO and the No. 2 executive was high (i.e., an adequate incentive for the latter was not present), CEO power was high and the corporate performance was negative.

The above having been clarified, compensation not only is a matter of the CEO and firm characteristics but also depends on the environment, with the industry and its corporate governance rules on compensation in primis. In this regard, as found by Coles et al. [88], if there is a high pay differential between one corporate CEO and the highest-paid CEOs within a group of similar firms in the industry, this can push CEOs to be riskier so as to increase the corporate performance and, thus, become more desirable in the eyes of another company (i.e., the so-called CEO tournament).

As a summary of all that we have explicated, with no doubt, we acknowledge the importance of separately considering, as has mostly been done to date, all the CEO attributes reviewed in this article and further discussed in this section. At the same time, however, we do believe that, in the future, how these attributes coevolve [89,90,91,92,93] will be the pivotal research question to address if both scholars and practitioners want to improve their understanding of how CEOs behave and how their behaviour can impact on the sustainability of corporate performance [94,95]. In particular, we think that an associated important question will be that of understanding the coevolutionary relationships between the attributes above and the different environmental systems in which CEOs are chosen, behave, and are, eventually, fired.

Finally, we also acknowledge that our review suffers from some limitations. The first is methodological, in that, while opting for a practitioner-oriented review, we have not adopted a strict systematic literature review protocol for collecting and analysing articles. The second limitation, instead, could be considered as conceptual and is in regard to our final, proposed framework; in fact, although from our analysis of the literature we have offered some potential theoretical trajectories among CEO attributes, we have again stressed that the contributions specifically investigating the link between these attributes and corporate sustainability are still fragmented. Thus, at present, this can limit the generalizability of the framework itself.

7. Conclusions

We believe that, in the future, CEOs can benefit from the results of this review work to improve their sustainable behavior [96]. In particular, they could consider that their effect on corporate sustainable practices can be positive if they build more harmonious relationships with their board members through collaboration and cohesion. This means that they should follow a path of power sharing with their board members; in fact, when accumulated only in the hands of CEOs, this power apparently produces a negative effect in terms of sustainable behaviour.

However, being harmonious and oriented to share power also depends on the personality and sociodemographic features of CEOs. In this case, CEOs affected by narcissism and/or hubris bring negative consequences to corporate sustainability; in contrast, being a high-tenured woman with a strong background in business administration is seemingly positive. In this regard, we acknowledge that personality and sociodemographic features represent inner attributes of CEOs and are, therefore, more difficult to be changed. However, we believe that CEOs should, at least, consider them when approaching CEO succession in other firms because they are elements that shareholders may take into high consideration when appointing a new CEO. Thus, in this vein, the insights from our work can be also beneficial to shareholders themselves.

In conclusion, future research could first adopt a systematic process in the collection and analysis of the extant literature on the topic. In their analyses, as we have also explained, scholars could also consider the potential endogeneity problem among the antecedents/consequences of CEO behaviour, thus also taking into account the methodological suggestions recently proposed [12,83]. Furthermore, scholars could also focus more on what CEO practices impact sustainable behaviour, which currently appears to be an underdeveloped line of research. However, these practices, such as consensus, attention, cohesion, comprehensiveness, and debate in decision making, should be studied with a close look at the CEO/board members relationship. This relationship is, indeed, a very important and recent line of research in the behavioural strategy domain [97] because it is focused on understanding the escalation of behaviour from the individual to the collective (in this case, from CEOs to board members).

In international business schools, positive examples of superstar CEOs are typically those we use for inspiring students when starting our general management classes at the undergraduate, graduate, and, especially, executive level. In parallel, negative examples of superstar CEOs are also what we often use to help students be aware not only of the opportunities but also of the threats of CEO life. This is why we firmly believe that improving the “scientific understanding” of CEOs will continue to be pivotal in the future and why we also believe that this understanding will, perhaps, require evaluating—always more objectively—their actions and even de-mythicize some of these if needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.; methodology, G.A. and M.C.; investigation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, G.A. and M.C.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, G.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Administrative Behaviour; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Bromiley, P.; Rau, D. Social, behavioral, and cognitive influences on Upper Echelons during strategy process: A literature review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 174–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, G.; Cristofaro, M. Hambrick and Mason’s Upper Echelons Theory: Evolution and open avenues. J. Manag. Hist. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, J.B.; Bundy, J.; Hambrick, D.C.; Pollock, T.G. The schackles of CEO celebrity: Sociocognitive and behavioral constraints on “star” leaders. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenbark, J.R.; Krause, R.; Boivie, S.; Graffin, S.D. Toward a configurational perspective on the CEO: A review and synthesis of the management literature. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 234–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wowak, A.J.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Steinbach, A.L. Inducements and motives at the top: A holistic perspective on the drivers of executive behaviour. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 669–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.J.; Jeong, S.H.; Graffin, S.D. Born to take risk? The effect of CEO birth order on strategic risk taking. Acad. Manag. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Finkelstein, S. Managerial discretion: A bridge between polar views of organizational outcomes. Res. Organ. Behav. 1987, 9, 369–406. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C. Top-management-team tenure and organizational outcomes: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangrow, D.B.; Schepker, D.J.; Barker, V.L., III. Managerial discretion: An empirical review and focus on future research directions. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 99–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Invest. Anal. J. 2016, 45, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, T.; Minor, D. CEO power, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: A test of agency theory. Int. J. Man. Financ. 2016, 12, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S. Power in top management teams: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 505–538. [Google Scholar]

- Bigley, G.A.; Wiersema, M.F. New CEOs and corporate strategic refocusing. How experience as heir apparent influences the use of power. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall Street Journal. In Facebook Deal, Board Was All but Out of Picture. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304818404577350191931921290 (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Magnusson, P.; Boggs, D.J. International experience and CEO selection: An empirical study. J. Int. Manag. 2006, 12, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Does founder CEO status affect firm risk taking? J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2015, 23, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S.A.; Lefen, L. An analysis of corporate social responsibility and firm performance with moderating effects of CEO power and ownership structure: A case study of the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, L.Y.H.; Thomas, T.; Wang, Y. Sustainability reporting and firm value: Evidence from Singapore-listed companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.J.; Sarkis, J. Does explicit contracting effectively link CEO compensation to environmental performance? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, T.J.; Hambrick, D.C. When the former CEO stays on as a board chair: Effects on successor discretion, strategic change, and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 834–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, S.V.; Valenti, A. CEO duality: Balance of power and the decision to name a newly appointed CEO as chair. J. Leadersh. Account. Ethics 2012, 9, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, P.; Datta, D. CEO successor characteristics and the choice of foreign market entry mode: An empirical study. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg. Tesla Seeks Independent Directors as Board’s Musk Ties Eyed. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-11/tesla-investors-press-for-more-board-members-without-musk-ties (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Kahneman, D.; Lovallo, D.; Sibony, O. The big idea. Before you make that big decision. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cristofaro, M. Reducing biases of decision-making processes in complex organizations. Manag. Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Nanda, V.K.; Silveri, S. CEO power and firm performance under pressure. Financ. Manag. 2016, 45, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Quigley, T.J. Toward more accurate contextualization of the CEO effect on firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.K.; Rajagopalan, N.; Zhang, Y. New CEO openness to change and strategic persistence: The moderating role of industry characteristics. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y. CEO hubris and firm risk taking in China: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, C.; Hambrick, D.C. How national systems differ in their constraints on corporate executives: A study of CEO effects in three countries. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 767–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, C.; Hambrick, D.C. Differences in managerial discretion across countries: How nation-level institutions affect the degree to which CEOs matter. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 797–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chung, C.Y. CEO overconfidence, leadership ethics, and institutional investors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Hambrick, D.C. It’s all about me: Narcissistic Chief Executive Officers and their effects on company strategy and performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 351–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, W.C.; Konig, A.; Enders, A.; Hambrick, D.C. CEO narcissism, audience engagement, and organizational adoption of technological discontinuities. Adm. Sci. Q. 2013, 58, 257–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H.; Chen, G. CEO narcissism and the impact of prior board experience on corporate strategy. Adm. Sci. Q. 2014, 60, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Pollock, T.G. Master of puppets: How narcisstic CEOs construct their professional worlds. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, E.; Maynes, T.D.; Badura, K.L.; Whiting, S.W. Examining the “I” in team: A longitudinal investigation of the influence of team narcissism composition on team outcomes in the NBA. Acad. Manag. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USA Today. Amid Mounting Bipartisan Concerns, Debate over Trump’s Mental Health Takes Off. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/ne ws/politics/2017/08/23/amid-mounting-concerns-presidents-mental-health-more-complicated-than-citing-narcissism-erraticism/490096001/ (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Rijsenbilt, A.; Commandeur, H. Narcissus enters the courtroom: CEO narcissism and fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, P.M.; Dagnino, G.B.; Minà, A. The origin of failure: A multidimensional appraisal of the hubris hypothesis and proposed research agenda. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, M.; Hambrick, D.C. Explaining the premiums paid for large acquisitions: Evidence of CEO hubris. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Qian, C.; Chen, G.; Shen, R. How CEO hubris affects corporate social (ir)responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1338–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, N.J.; Hambrick, D.C. Conceptualizing executive hubris: The role of (hyper)core self-evaluations in strategic decision-making. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y. The social influence of executive hubris: Cross-cultural comparison and indigenous factors. Manag. Int. Rev. 2013, 53, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telegraph. Sepp Blatter Delivers Bizarre Winner’s Speech after Winning FIFA Election. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/football/sepp-blatter/11639960/Sepp-Blatter-delivers-bizarre-winners-speech-after-winning-Fifa-election.html (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- CEOgenome.com. What Does It Take to Become a CEO Today? Available online: http://ceogenome.com/about/ (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- Wang, H.; Waldman, D.A.; Zhang, H. Strategic leadership across cultures: Current findings and future research directions. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.K. The impact of CEO characteristics on corporate sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Res. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, L.Y.H.; Nguyen, M.H. Board diversity and business performance in Singapore-listed companies the role of corporate governance. Res. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2018, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Akbar, A. Does increased representation of female executives improve corporate environmental investment? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S. Top management team diversity: A review of theories and methodologies. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, G.; Cristofaro, M. Upper Echelons and executive profiles in the construction value chain. Evidence from Italy. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 47, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Japan Times. Japan’s CEOs: Underpaid and Underwhelming. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/01/06/business/japans-ceos-underpaid-underwhelming/#.WoxK7KOZPq0 (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- Abatecola, G.; Farina, V.; Gordini, N. Board effectiveness in corporate crises. Lessons from the evolving empirical research. Corp. Gov. 2014, 14, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuropeanCEO. Handelsbanken Removes CEO Due to Culture Clash. Available online: https://www.europeanceo.com/business-and-management/handelsbanken-removes-ceo-due-to-culture-clash/ (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Carpenter, M.A. (Ed.) The Handbook of Research on Top Management Teams; Edward Elgar: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Business Insider. 15 Fortune 500 CEOs Who Got Their Start in the Military. Available online: http://www.businessinsider.com/15-fortune-500-ceos-who-got-their-start-in-the-military-2015-8?IR=T (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Wall Street Journal. Johnson & Johnson CEO’s Pay Rises 48%. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/johnson-johnson-ceos-pay-rises-48-1426085586?mod=mktw (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- CNBC. P&G CEO McDonald Retiring Due to ‘Distraction’ of Critics’ Attention. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/id/100757475 (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- New York Times. G.M. Reports Big Profit; Europe Lags. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/17/business/gm-reports-its-largest-annual-profit.html?_r=1&hpw (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Fortune. 7 CEOs with Notably Devout Religious Beliefs. Available online: http://fortune.com/2014/11/11/7-ceos-with-notably-devout-religious-beliefs/ (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Wall Street Journal. Tyson CEO Counts Chickens, Hatches Plan. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703431604575468041244773052 (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Whiters, M.C.; Fitza, M.A. Do board chairs matter? The influence of board chairs on firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberson, S.; O’Connor, J.F. Leadership and organizational performance: A study of large corporations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1972, 37, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. The population ecology of organizations. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 929–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveman, H.A. Follow the leader: Mimetic isomorphism and entry into new markets. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 593–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.A.; Brem, A. Sustainability in SMEs: Top Management Teams behavioural integration as source of innovativeness. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, T.J.; Hambrick, D.C. Has the CEO effect increased in recent decades? A new explanation for the great rise in America’s attention to corporate leaders. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalensee, R. Do markets differ much? Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelt, R.P. How much does industry matter? Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roquebert, J.A.; Phillips, R.L.; Westfall, P.A. Markets vs. management: What ‘drives’ profitability? Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahan, A.M.; Porter, M.E. How much does industry matter, really? Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Schoar, A. Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. Q. J. Econ. 2003, 118, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Ketchen, D.J.; Palmer, T.B.; Hult, T.M. Firm, strategic group, and industry influences on performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A. The effect of CEOs on firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahan, A.M.; Victer, R. How much does home country matter to corporate profitability? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, W.; Nitin, N.; Bharat, A. When does leadership matter? A contingent opportunities view of CEO leadership. In Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice; Nitin, N., Rakesh, K., Eds.; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Chapter II. [Google Scholar]

- HBR.org. The Best-Performing CEOs in the World 2017. Available online: https://hbr.org/2017/11/the-best-performing-ceos-in-the-world-2017 (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Walls, J.L.; Berrone, P. The power of one to make a difference: How informal and formal CEO power affect environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 145, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Bendahan, S.; Jacquart, P.; Lalive, R. Causality and endogeneity: Problems and solutions. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Day, D.Y., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Core, J.; Guay, W. The use of equity grants to manage optimal equity incentive levels. J. Account. Econ. 1999, 28, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, F. Managerial Attributes, Incentives, and Performance. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1680484 (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Giroud, X.; Mueller, H. Corporate governance, product market competition, and equity prices. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 563–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F. Mutual monitoring and corporate governance. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 45, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F.; Wang, A.Y. Industry tournament incentives. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2018, 31, 1418–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, G.; Belussi, F.; Breslin, D.; Filatotchev, I. Darwinism, organizational evolution and survival. Key challenges for future research. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, D. What evolves in organizational co-evolution? J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafferata, R. Darwinist connections between the systemness of social organizations and their evolution. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, I.P.; Collard, M.; Johnson, M. Adaptive organizational resilience: An evolutionary perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 28, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniccia, P.; Leoni, L. Co-evolution in tourism: The case of Albergo Diffuso. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Perkins, K.M.; Serafeim, G. How to become a sustainable company. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B.W.; Walls, J.L.; Dowell, G.W.S. Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crainer, S.; Dearlove, D. (Eds.) Dear CEO. 50 Personal Letters from the World’s Leading Business Thinkers; Bloomsbury: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.; Lovallo, D.; Fox, C.R. Behavioral strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1369–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).