1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Purpose of the Study

“The rapid growth of the middle class was one of the most important supports sustaining South Korean society in the second half of the 20th century. The photograph of a family of four, smiling and happy, with a decent job, an 85-square-meter apartment, and a medium-sized car, is a KS mark (Korean Standards) image that shows the reality of material abundance through high growth [

1].” As such, in South Korea, the history of 20th century design is the history of the country’s middle class, and the history of the middle class is actually that of apartments. South Korea has demonstrated an unprecedented phenomenon, in which apartment complexes spread across the urban landscape in a short period of time and came to completely dominate the housing culture. As of 2010, these apartment complexes account for about 58.9% of the total domestic housing, and the proportion of apartments in annual new housing constructions is over 71.6% [

2]. This shows that the apartment has become the typical type of residence for urban life in South Korea.

Lim and Kim (2015) describe the housing policy, the industrial structure, and the mechanisms of the apartment market, driven by the government and large private construction companies and desired by people, as follows: “Despite paying money in advance, they did not receive the type of housing they wanted. At the time, more than 90 percent of the people did not want an apartment, but the only type in supply was the apartment. People paid money in advance, but bought a house that they did not want. They also picked the floor that they would live on by luck of the draw. It is quite absurd. But instead of following these strange procedures, people could buy apartments at cheap prices” [

3]. In other words, the mechanism of apartment sales allows construction companies to earn a profit at little cost, and the government to earn money through the sale of land and the bond market. On the other hand, it also stimulates the desire to be incorporated into the middle class, generating a profit margin through the people who buy apartments.

It should be noted, however, that even people who want to buy an apartment do not prefer the space composition of the existing apartment. In the course of the production and consumption of apartments, because the logic of the government and large private construction companies have received priority over that of the consumer, conflicts and discord with the actual requirements and lifestyles of residents have been and continue to be experienced [

4]. The apartment complex, which was regarded as an ideal type of residence in South Korea under the military regime in the era of industrialization, is now arriving at a new turning point, due to changes in social structure and lifestyle. As French geographer Valeri Gelezeau, writes in the conclusion of the “Apartment Republic,” “The large apartment complexes turn Seoul into an ephemeral city that can-not last long” [

5], and a variety of desires are inherent to everyday life that cannot be accommodated under the name of convenience.

Therefore, this study focuses on newly emerging lifestyles, resulting from the transition of social structure, and analyzes the characteristics of residential spaces that reflect them. This is an attempt to reconcile residential spaces with the lives lived in them, in order to overcome the limitations of 20th century domestic urban housing—represented by the monotonous and uniform apartment complexes aimed at the middle-class nuclear family—and realize the sustainable urban housing.

1.2. Method and Contents of the Study

There are several viewpoints dealing with contemporary trends in architectural and urban design. Some are focusing on philosophical aspects. Others are emphasizing on the scientific contribution of the authors. Frequently, those are mixed together. Based on this, the methods on how to make a critical approach can be classified [

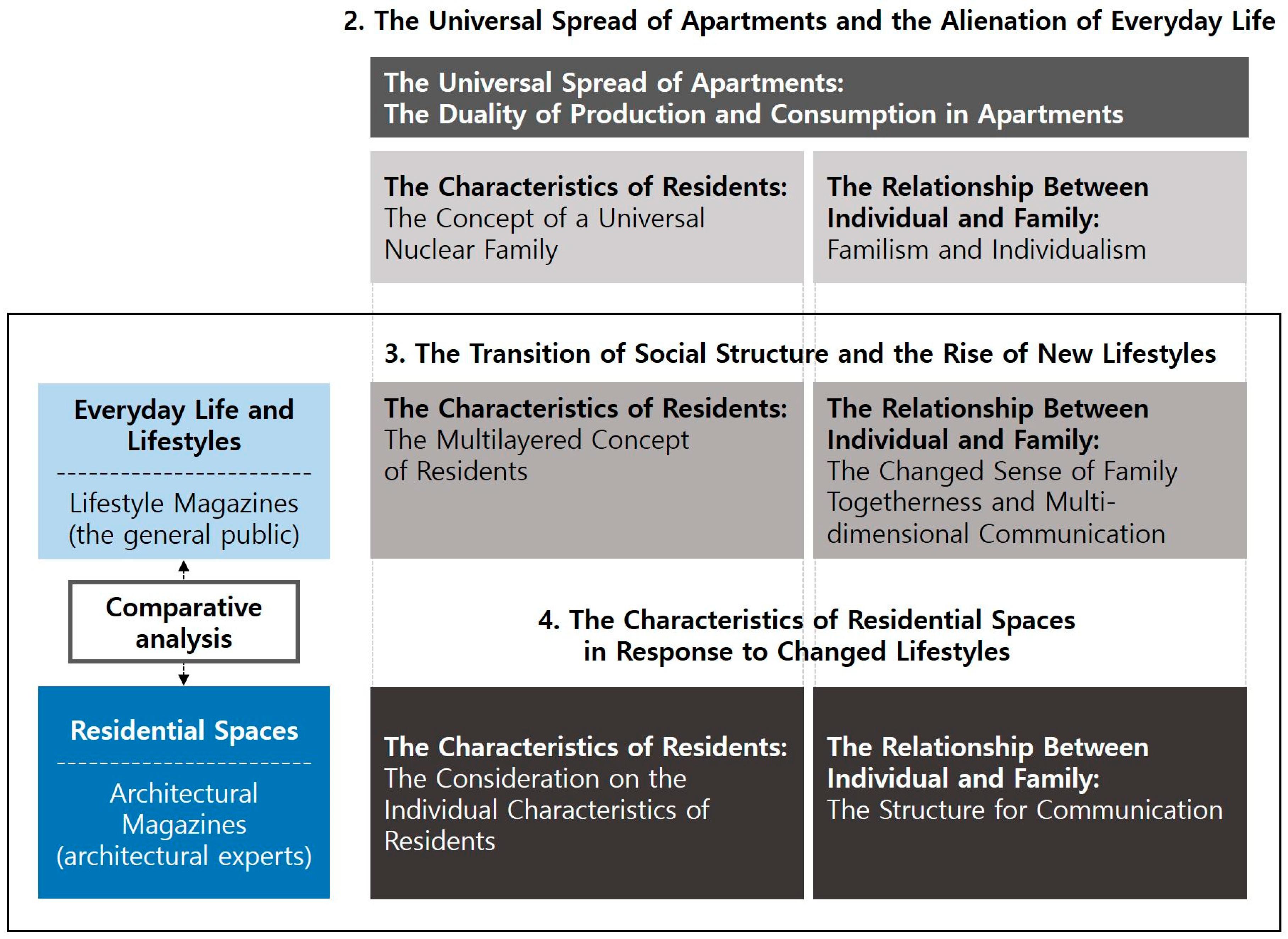

6], and this study follows the new directions in the planning theory method. The theoretical content is based on the transition of social structure and the rise of new lifestyles including the changed concept of the user and relationship between family members. This study also adopted a comparative analysis between the everyday life and residential spaces for a critical approach of this study.

To this end,

Section 2 discusses the reasons behind the universal spread of apartments in South Korea and analyzes the alienation of everyday life that comes with this process. In particular, it explores the phenomenon of the double alienation of everyday life due to the overlap of the industrial and consumer capitalist paradigms in the process of rapid economic growth. It also examines the universal and abstract concept of the user as the supply target of the apartment, and the relationship between the spatial characteristics of apartments and the lives lived in them.

Section 3 analyzes changes in the characteristics of everyday life and lifestyles resulting from a transition in social structure, by focusing on articles about housing in lifestyle magazines. In order to examine changes in “the characteristics of residents” and “the relationship between individual and family” through specific cases, interviews with residents that include references to lifestyles were selected as the main objects of analysis.

On the other hand, through an analysis of architectural magazines,

Section 4 discusses perspectives of architectural specialists on the interpretation of contemporary lifestyles and the characteristics of residential space planning supporting these changes.

Section 4 also analyzes the consciousness of architectural experts of “the characteristics of residents” and “the relationship between individual and family,” and the presence of these aspects in architectural solutions.

Interviews and articles of residential spaces published between 2015 and 2017 were the primary research material for

Section 3 and

Section 4. In the case of lifestyle magazines, “House Full of Happiness,” “Maison”, and “Living Senses” were selected, and

Section 3 was based on the previous studies of our researchers. In the case of architectural magazines, “Space”, the representative monthly architectural magazine of South Korea, was selected. The “Space Academia” section of this magazine was also listed in the A&HCI. “Space” magazine focuses on domestic architecture, providing monthly case studies of housing trends. In the analysis of architectural magazines, all case studies related to houses and housing in the last three years were surveyed. The logical connections between chapters are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Finally, in the concluding chapter, the similarities, differences, and limitations between the viewpoints of the general public and of architectural experts are examined through a comparative analysis of lifestyle and architectural magazines. Through this comparison, a basis is provided for showing that the living environment of the existing apartments is not consistent with the aspects of everyday life sought by actual residents. This also provides an opportunity to explore the essence of contemporary everyday life and the characteristics of residential spaces that urban housing projects should include.

2. The Universal Spread of Apartments and the Alienation of Everyday Life

The most interesting aspect of domestic urban housing in South Korea today is that a single type of housing and apartment complexes, dominates the whole country and occupies a unique position, which is unparalleled in comparison with the global situation. Despite criticism by experts of the spread of high-rise apartment complexes, these simple, functional and convenient apartments have become, for the middle class, a means of preserving and growing assets under conditions of high inflation.

Therefore, in

Section 2, we analyze the causes for the rapid spread of apartments in South Korea in terms of both production and consumption, showing that the paradigm of the inherent capitalist social structure leads to an alienation of everyday life in the apartment. It also examines the universal and abstract concept of residents, as well as the effects of pursuits of privacy and independence on the relationship between the individual and family.

2.1. The Universal Spread of Apartments: The Duality of Production and Consumption in Apartments

The development of apartment complexes in South Korea began in the 1960s, as a means to solve the housing problems of urban citizens, resulting inevitably from the processes of industrialization and urbanization, in ways similar to the process of western modernization.

South Korea has experienced high economic growth and modernization based on the capitalist mode of production in a short period of time, which has led to major changes in the housing culture without any serious concerns about value. As a result, concepts and ideas developed within a long-term historical context in the West have been imported into the Korean context without significant exploration, and have come to be seen as core principles that govern our everyday life. In other words, the introduction of physical spaces of modern western urban housing has been spreading the ideas which are inherent in them.

From the perspective of production and supply, within the ideologies of rationality and efficiency espoused by modern industrial capitalism in the West, the user or resident is conceived of as a universal and abstract concept, and the housing production is structured on the basis of the quantitative principle, with standardized designs that prioritize economy. In addition, the values of housing planning are reduced to rational principles such as function and efficiency, along with a general logic of strengthening privacy in the form of familyism, individualism and equality. Furthermore, the composition of residential spaces is consistently function-oriented, focusing on the segmentation and division of space. In the process, space is internalized and social relations and communication are overlooked. Further, the value of “convenience,” newly experienced as a result of this process, has emerged as an important residential value that justifies this trend [

7].

On the other hand, the universality of the concept of residents, in terms of production and supply, is linked to the product value of housing, which is ordinary and common from the perspective of commodification. In addition, the interests of the government and private construction companies, and the manner of pre-sale, with restrictions on sale price for the convenient mobilization of funds, led to another narrow economic logic, of real estate speculation. Along with this, while the quantity and uniformity of the standardized design allowed for easy quantification of the value of the house, apartments became a symbol of wealth and status, and a basis for socioeconomic hierarchy. In this way, the logic of production and supply of apartment complexes became linked to the logic of consumption and demand, enabling the universal spread of apartments by accelerating both logic through interaction [

8].

In other words, under the special circumstances of compact economic growth in South Korea, the most uniform and economical modern housing type led to an unusual situation of universal spread due to the simultaneous combination of modern industrial and consumer capitalism. This can be seen as a special combination, since the 1960s, of low-income housing provided for the reproduction of labor in the city of industrial society, and houses of consumption that realize the desire for difference in modern consumer society.

As a result, everyday life is reduced to the structuring of apartments as a dominant urban housing type, which does not reflect the diverse requirements of changed lifestyles, and continues the logic of modernized and standardized mass housing type from the perspective production and supply. On the other hand, there is a distortion of everyday life through the manipulation of modes of consumption, through which a housing type involving modern and uniform mass production is sold as a product reflecting social stratification and the various demands of the contemporary era. This characteristic reflects the tendency of commodification of domestic urban housing and can be understood as a reduction and distortion of everyday life that is revealed at the interface between modern production method and contemporary consumption tendencies.

2.2. The Characteristics of Residents and the Relationship Between Individual and Family in Apartments

In

Section 2.2, we will examine “the characteristics of residents” and “the relationship between individual and family” in apartments, which are wide spread in South Korea

2.2.1. The Characteristics of Residents: The Concept of a Universal Nuclear Family

When a massive supply of housing was sought to be created in a hurry, the demand only centered on the basic facilities, structural stability, and adequate residential area. Therefore, individual variations among residents was not considered because it was more efficient to estimate an appropriate size for housing and to provide standardized housing uniformly to all.

The abstract criteria for residents of apartments originated in the 1970s and 1980s, assuming a universal family type in the production of housing units. At this time, the universal family type was the two-generational nuclear family composed of a couple and their two or three children, and this type was uniformly applied to all housing supply [

9]. In addition, in the universal nuclear family type, there was a division between the ideal roles of men and women. The husband, who was the father, worked outside, while the wife was to take care of housework as a housewife. This unit model was formulated as a standard ideal, structuring the mass production system. This is the reason why the spatial composition of most apartments is basically the same while there is only a difference in scale depending on the area. It is very natural that the type of housing or residential space should vary depending on characteristics of family members, but this has been neglected in apartments. In a situation where housing was absolutely insufficient, the lives and lifestyles of residents were forced to conform to the framework set by the supplier.

As a result, in the 1980s and 1990s, the number of apartments increased rapidly. At that time, the percentage of nuclear families also increased. In 1995, the proportion of nuclear families, which was 71.5% in 1985, reached 80.9% [

10]. But it is not easy to determine the cause and the result in this case. However, the plan composition of apartments was designed for a nuclear family, and hence was not suitable for extended families. This situation may have meant that there were few alternatives to choose from outside the category of the typical and universal nuclear family. Furthermore, even in the case of a nuclear family, the concept of the resident was reduced to minimal functional requirements, an intersection that could be extracted commonly from all nuclear families. As a result, there was limited opportunity for reflecting varied lifestyle elements such as personality, differences, and creative desires.

This kind of uniformity based on almost the same spatial logic, while pursuing the most common and universal style in order to presume a general nuclear family and increase the marketability, is not the problem of only space itself. This, in turn, resulted in a standardization of the contents of life. In other words, the standardized physical uniformity of apartments structured residents’ everyday lives into a pre-packaged state, creating the contents of monotonous and insipid life [

11].

2.2.2. The Relationship Between Individual and Family: Familism and Individualism

Housing in modern society is generally considered a private space dedicated to family life. As most people tend to accept this presumption, the most dominant social philosophy of housing in contemporary times is, “housing is always privatized” [

12]. In particular, the apartment is a more family-centered space than any other housing type [

13]. By reducing the living space into a set of rooms and balconies, it tends to make the stage of life itself introverted, and structured by the values of familism and individualism [

14]. This intimate space, where most nuclear families live, is essentially a type of housing that keeps people away from problems in the neighborhood and larger social concerns.

Just as apartment complexes are disconnected from the external space and isolated from the urban space due to the emphasis on privacy, familism, and private ownership, functional differentiation as well as the differentiation of personal space are prominent in the units of apartments. That is, under individualism, the shared space within the family gradually decreases and the life of the residents becomes more independent. The shielded personal space also guarantees anonymity within a family, which reflects the personal attributes of individuals in modern society, where self-management and self-control are given priority [

15].

Furthermore, the development of the Internet, computers, and smart devices, combined with the characteristics of strongly independent rooms, has weakened the existing minimal family togetherness and further isolated individuals within the family. As Jeon (2010) writes, “For example, in the old days, there were opportunities to meet parents or siblings in the living room several times each night, on the way to the bathroom, telephone, television, or water. But now, you can make calls on your mobile phone and watch TV on DMB (Digital Multimedia Broadcasting). Would not it be better to use the word ‘personal appliance’ instead of ‘home appliance’?” [

13]. The essential question then arises as to what the meaning of the family in apartments really is. Individualism in an apartment is not entirely a matter of physical space. However, the independent and separated spatial structure of the apartment, which ignores communication and relationships in various ways, plays a role in creating or encouraging such a situation of minimal relationships.

3. The Transition of Social Structure and the Rise of New Lifestyles

Despite the growth of a creative class and the increasing prominence of the demands of creative lifestyles in the 21st century—due to the transition to a capitalist social structure centered on human creativity—architectural characteristics are still not far from the paradigm of industrial capitalism, based on efficiency and convenience. Nevertheless, the new capitalist paradigm that emerges with the creative class is permeating residents’ everyday life and diffusing new lifestyles that are very different from the earlier values or norms that the apartment assumed. As a result, the alienation of everyday life in the typical urban housing type of South Korean apartment complexes is becoming more prominent at the present time, when new lifestyles are emerging. Thus, there is a growing interest in lifestyles due to the transition of social structure.

Therefore, in

Section 3, we will analyze lifestyle magazines aimed at the general public from the perspective of “the characteristics of residents” and “the relationship between individual and family”. Through this analysis, we will examine changes in family relationships, where privacy was earlier considered a top priority, and the new characteristics of residents that are not included in the universal nuclear family concept.

3.1. The Characteristics of Residents: The Multilayered Concept of Residents

The existing concept of residents is not only universal and abstract, but also overlooks individual personalities and generational differences. On the other hand, with the emergence of a creative class, most articles appearing in recent lifestyle magazines are directed at people engaged in the creative field rather than the general populace of white-collar office workers.

Of course, the nature of lifestyle magazines creates a tendency to prefer people with artistic skills. But the scope and titles of creative occupations, which were once limited to painters, sculptors, or writers, have dramatically diversified. Advertising planners, marketers, food coordinators, features editors of magazines, decorators, fairy-tale writers, design gallery operators, beauty editors, style directors, bassists of indie bands, freelance marketers, food stylists, Korean dessert cafe chefs, car designers, graphic designers, illustrators, displayers, fashion magazine editors, producers, and directors of living contents are just some of the kinds of professionals that can lay claim to the title of creative occupations in lifestyle magazines. They seem to be more interested in positively revealing the contents and interests of what they are doing rather than emphasizing their positions in the companies.

It is interesting to note that even though individuals holding these job titles are not directly related to the arts, they have many diverse professional hobbies related to the fields of art and culture. Through these, they constantly pursue a reshaping of their personalities and identities. Cultural capital has now been emphasized as a source of creativity that potentially sustains the materiality of capital, and has been cultivated and expressed through various hobbies and interests. The scope of cultural capital has also tended to be more professional and broader, with interests and values attached to the personal interests of individuals, rather than confining them to so-called high-class cultures that emphasized class identity, as in previous eras. Therefore, such individuals are very active in finding a variety of props that reveal their tastes and personalities, much like collectors. They are also interested in experimenting the integration of diverse and heterogeneous cultures, rather than simply following high-level cultures that reflect a current fashion or a class identity. Further, they want to do such experiments in their residential spaces. As one resident said, “As I became interested in decorating the house, I realized what I liked and found true happiness” [

16]. That is, they “mature with the house” [

17].

However, there is a limit to the extent to which the changing characteristics of residents can be reflected in apartments. Due to the inherent limitations of apartments, which have uniform proportions and spatial compositions, the types and layout of furniture are almost similar in every room. In an apartment where not only the appearance, but also the interior space, is uniformly structured, “the promotion of competition and imitation in the cultural aspect paradoxically results in cultural equalization or equality”. Reference [

15] Under the same spatial conditions that can easily be compared with the neighboring house, the tendency of collective uniformity of interior decorations encouraging competition and imitation, regardless of the distinctive character of families, is a phenomenon commonly seen in apartments [

18].

Also, if the existing concept of residents was abstract and universal and focused on the minimal functional requirements of individuals without considering difference and personality, the concept of residents in apartments modeled a typical middle-class nuclear family as an anonymous set of these individuals. However, as individual personalities and identities are now maximized, the household composition of these individuals has also become quite diverse. Not only has the numerical composition of households diversified, but even in the case of a typical nuclear family, the contents of life have been extended to the extent that it is difficult to predict their patterns as in the past. In other words, the bland white-collar workers of the middle-class nuclear family that apartments assumed have now changed into a variety of individuals in unspecified combinations, engaged in creative occupations and constantly devoted to their personalities and hobbies [

4].

3.2. The Relationship Between Individual and Family: The Changed Sense of Family Togetherness and Multi-Dimensional Communication

Since the spatial composition of apartments is basically connected with the ideology of workers’ houses in the era of industrialization in the West, the principle of reduction of social spaces and internalization has been going on within the housing unit.

In apartments, “there is little or no economic or social activity, and it has a spatial structure that does not support it while there is only minimal family togetherness, such as in eating, sleeping, resting, and playing” [

19]. Functionally hybrid spaces were excluded as far as possible and rooms were clearly divided. In the process, the personalization of family members is accelerated in the apartment. So too is familism resulting in a lack of local communities. In fact, familism can be seen as a means toward material happiness, rather than genuine communication and togetherness between family members.

The existing familism was oriented towards a personalized family in which the achievement of the individual’s goal was the priority under a patriarchal family atmosphere. In recent years, however, it has become necessary for family members to constantly feel each other’s existence even when they are engaged in their own work, and to pursue communication and exchange about lifestyles in various ways. In other words, in order to feel the sense of being together while maintaining autonomous lives, attempts to connect spaces and communicate more actively have become preferred, rather than the existing composition of disconnected and compartmentalized rooms. Thus, it is important not to be in perfect disconnection, but to share flexibly so that they can feel each other’s existence while they are engaged in their own work. It is hoped that “the feeling of being together even if the family spends their time elsewhere” [

20], or “the feeling that they are together without being disconnected even if family members are in different spaces by connecting and opening public spaces” [

21] can be created. This means that people now want a spatial composition that allows families to be together or be separated, “so that it can be used together or separately” [

22].

To this end, some of the solutions most often attempted are replacing existing firmly closed walls and narrow-width hinged doors with open walls, glass windows, and sliding doors. In particular, as open plans break the gap between space and space, efforts to share the sense of being together while providing privacy through glass doors or sliding doors are more frequent, rather than complete open plans.

In addition, there are efforts to transform shared spaces such as corridors and staircases, which are now attracting attention as social spaces, into spaces that do not only serve for circulation but also as spaces with programs. “The family room, which has a staircase for sitting between two spaces, was designed as a space where families could gather and enjoy something, such as reading books or watching movies in the corridor space. (...) This is due to rotating circulation. (…) It allows people to stroll indoors like a walk and communicate naturally” [

23]. In other words, such spaces are not simple spaces for circulation, but spaces that provide possibilities of meeting or communication.

4. The Characteristics of Residential Spaces in Response to Changed Lifestyles

In

Section 3, we examined changes in the attributes of everyday life and lifestyles through lifestyle magazines in terms of “the characteristics of residents” and “the relationship between individual and family.” In

Section 4, we will discuss the characteristics of residential spaces that support changing lifestyles found in descriptions of residential projects in architectural magazines. In the analysis of lifestyle magazines aimed at the general public in

Section 3, interviews with residents as clients were the main objects of analysis. Now, in the analysis of architectural magazines in

Section 4, we will discuss the perspectives from which the newly emerging lifestyles and the characteristics of residential spaces supporting these changes are being interpreted, through the eyes of architectural experts, including architects and critics.

4.1. The Characteristics of Residents: The Consideration on the Individual Characteristics of Residents

In

Section 3.1, we saw that the universal and abstract concept of residents that overlooked the individuality and difference of each resident by modeling a typical anonymous middle-class nuclear family has recently faced multi-layered and broad changes. Lifestyle magazines have focused on the various individual characteristics of residents and most of them are accompanied by detailed explanations about these characteristics. We were also able to understand that the composition of these individuals’ households reflected various combinations that go beyond the conventional nuclear family.

However, while most architectural magazines presuppose a basic understanding of residents’ interests and tastes as fundamental elements of housing planning, the descriptions of residents are abstract or not detailed. In addition, due to the nature of architectural magazines, there are many cases where houses are visited and photographed before the lives of their residents are fully set up. Therefore, critics have sometimes observed a lack of a glimpse of real life. As one critic, pointed out, for instance, “One thing we missed is the actual daily lives of the family, because they are currently staying overseas” [

24].

4.1.1. The Pursuit of Architectural Plasticity (Intent on the Aesthetic Value of the Exterior)

Since the residential projects introduced in architectural magazines are alternatives to uniform apartment complexes, it is necessary to fundamentally examine the personalities and differences of residents of these residential spaces. This means that it is more necessary “to cope with the demand for housing that accommodates various personalities instead of the uniform apartment” [

25]. Especially in recent years, as not only high-class houses but also middle-class houses have been able to be designed by architects, the demand for houses designed by architects is vertically expanding. In this situation, detached houses that aim to maximize the individual characteristics of residents dominate housing cases discussed in architectural magazines. Most of the cases referring to the personalities of clients, however, have a tendency towards architectural plasticity, that is, the aesthetic value of the exterior, rather than the reflection of everyday life or lifestyles in them.

In the case of an architect who had to plan several houses in the same area, he had to create designs different from his former projects because, the building owners wanted houses that are unique and different from others. For instance, “Three concrete boxes will pile up in order, but horizontal band windows will be inserted which will create an interesting form” (

Figure 2, left) [

26]. “The windows were uniquely designed to make changes in the plainness of the box-shaped structure” [

27]. In order to capture the personalities of the client through the visual form, sometimes the form takes precedence over the space. For example, “The design of this house came from a formative idea sketch that was drawn some time before.” [

28]. As the architect concerned states, “It is quite experimental as a house, but it was realized with much unexpected appeal to the client” [

28]. In other words, the desire for the pursuit of architectural plasticity is not caused only by the architect’s personal desire but is supported by the demand of the clients that their personalities be reflected.

The same is true of the case where, “Why did the architect design a house with acute angles like a butterfly? (...) First, the architect referred to the taste of the public who favor unique forms.” (

Figure 2, center) [

29]. Similarly, as in “The architect seems to have been intent on making this house as ‘different’ as possible from the rest of the village, rather than to design a home that abides with the standards of ‘a house within the village’” (

Figure 2, right) [

30]. It is only a matter of realizing that decent detached housing areas in new towns of South Korea have become an amalgamation of different single houses that refuse to conform to each other, using their outer walls to astutely stand with their backs to the road.

The tendency to pursue visual spectacles in the exterior of a residential project is associated with a variety of desires. However, among them, the commitment to a formative invention for a unique appearance is made possible by the curious melding of the exhibitionist desires of clients with the achievement-oriented desires of architects. Thus, it has been correctly observed: “Two broad categories diverge among houses that may be described as ‘having the architect’s touch’ due to the amount of effort apparent in their form. First, there is the group of homes that easily catch one’s eye, with ample application of all sorts of exotic and newfangled materials, as if having been sponsored by an architectural materials exhibition. These houses are shouting out “please look at me!”, wriggling in all sorts of contortions and doing whatever it takes to stand out, despite their rather limited circumstances. Another branch of architecture is made up of simpler forms, with a more restrained use of materials, as if to say “I don’t really want to mix with the jumbled up lot of this village”. Although they may turn their backs in a somewhat modest pretense, it seems that deep within, they also wish to declare ‘please look at me’” [

31].

Designing a detached house contains both the request for universal convenience and a desire to own something unusual. The various styles of houses in a newly developed village of detached houses have resulted from choices between these two values. When the balance leans towards uniqueness, “It is the exterior of the building that most easily reveals the desire of the architect and the client” [

29]. In the works that pursue plasticity in this way, the explanation of the technical problems such as structure, material, detail, construction cost, etc. to realize the interesting form and the formative features is what receive focus, rather than the story about everyday life.

On the other hand, criticism that rejects the social environment in which aesthetic beauty or images of the spectacle are obsessed over, appears just as much as tributes to plasticity. Such articles criticize the special domestic tendency in which the formative composition of spectacles occupies the core of architectural design in the modern society, where images are more important. Thus, for instance, “This house provokes one’s curiosity from the outside. From the perspective of creating relations, the house may seem belligerent. (...) Is not this the result of emphasizing what is seen outside of the building, and not trying to make a relationship between the inner space and the outer skin?” [

32]. Similarly, “I thought that the front of the house was extremely beautiful. (...) When a building’s front is so incredibly beautiful, I feel a sense of repulsion. (...) Architecture in the cities of South Korea does not have any given typology. More precisely, it consists of weak types and forms. The forms of the past are excluded, and enough time and effort has not been invested into developing a new type. To us, all buildings have new formations, and all that the architect can rely upon is the focus on the visual spectacles and the styles of form” [

33].

Sometimes, architects seek a technically demanding solution for plasticity, which has also been criticized: “However, houses designed with strong sculptural forms are often prevented from having spacious windows and doors for cross ventilation, as they are recognized as a threat to the composition of the facade. Thus the architect used an air conditioning system to counter the issue of ventilation. However, it couldn’t have been an easy task to persuade the clients to apply a system solely dependent on mechanical facilities rather than natural ventilation in such a small house, especially when considering logistical factors such as cleanliness, efficiency, cost-effectiveness and maintenance” [

30].

4.1.2. The Pursuit of the Distinctive Spatial Characteristics of Each Room

If the consideration of the characteristics of residents is revealed as plasticity in the morphological dimension, it is realized as the distinctive spatial characteristics of each room in the spatial dimension. If all of the rooms in apartments are uniformly located in the south and seek to have a similar size, proportion, height, and atmosphere, the cases in architectural magazines involve individual characteristics for each room, in order to create a difference of character for each space, rather than a homogeneous atmosphere. In other words, there is a tendency to pursue a unique mass and changes in cross-section beyond the spatial characteristics of apartments, which are planned by dividing the rectangular mass into homogeneous rooms with the same height of 2.3–2.4 m.

There are also cases of where, “The black boxes and the white boxes counter against each other in an irregular manner, creating changes in the density of an array of narrow, wide, low and high spaces” (

Figure 3, left) [

32]. Or, “Even as the house is open, rather than being presented as one undifferentiated volume, the ceiling height varies drastically, defining diverse areas of use. At the upper levels, the rotated roof creates dynamic relationships between the regularity of rectangular rooms and the irregularity of the varied ceiling planes. It constantly and subtly ‘unsettles’ the occupants, suggesting varying perspectives, movements, and lighting conditions that change with their specific position” (

Figure 3, center) [

34].

For this purpose, critics have been accepting of attempts to partition space within a cubic volume, rather than a planar spatial division as in apartments. Thus, “This house has an exterior form reflected into the interior and is organized with various forms and heights. The organization of the entire space is consolidated into one through the outer cover with required programs stacked like boxes. The gap between the boxes and the cover was connected to create different forms of spaces. Such organization makes the room I saw in the plan a small space, but it feels rather spacious. One of the house’s biggest advantages is the various spaces created through the structuring of the limited space” (

Figure 3, right) [

35]. The result of such three-dimensional planning is a different architectural experience and spatial play than the interior of the existing monotonous apartment units. Furthermore, more positively, by dispersing individual rooms on the ground, “Each space not only features different main materials—glass, concrete, steel, and stone—but also differing forms of primary archetype-houses built with a frame, built from masonry, laid on the ground, dug into the earth, deeply shadowed against the sun, and left wide open towards the sky” [

36]. Thus, it explores various fundamental forms of architecture.

On the other hand, rather passively, “the wedge-shaped bathroom and terrace were created separately from the square main rooms that can be monotonous” [

37], leading to a special spatial experience without deviating significantly from the functional and convenient plan of existing apartments. Alternatively, the corners that have special features and atmosphere are combined with an existing general plan, so that activities taking place in these special spaces are connected to an external yard or view. For example, “The house has an unusual plan, which introduces a corner space that gives a unique character to the individual spaces. These spaces include a sitting-style master-room corner for the parents, a work space/study corner for the father, a make-up corner for the mother, a piano corner for the daughter who majored in music, and a sports-equipment corner for the hockey-loving son” [

38].

Although architectural magazines have tended to accept the trends of pursuing formative spectacles in the form as a main purpose negatively, they were favorable towards spatial diversity, taking a critical standpoint on cases where such spatial experiments were lacking. A monotonous and homogeneous spatial composition containing the same conditions of view and light similar to apartments is criticized, for example, “However, this attempt, which ended up opening the view of all room (including the guest room on the 2nd floor) only in a southerly direction, has resulted in completely cutting off the view that is caused by the ranking of each room or that is found in the sequence from the circulation flow by chance” [

39]. In addition, as in another case, “Another point is that the space could have been better if the exterior allowed the interior identities to permeate naturally outwards” [

40]. While an unconditional and spectacular appearance is criticized, designs that do not reflect a unique interior space in the exterior are also seen with regret.

4.1.3. The Passive Response to the Future Life-Cycle Changes

The plasticity of architecture based on the client’s personality and the will to unusual interior spaces, however, are not positively associated with the variability or flexibility concepts of architecture that reflect the changes in family members’ characteristics or future life-cycle changes that are generally expected. It tends not to be prepared specifically for an unspecified future, although the imminent future is considered to some extent. For instance, “As a house for a family of four, the interior space was planned bearing in mind the fact that the children would move out of the house in the not-too-distant future” (

Figure 4, left) [

41]. Alternatively, “The relatively large master bedroom zone, with an attached dressing room and bathroom, is placed in the public space of the first floor, a requirement laid down by the client, who was making preparations for his golden years” (

Figure 4, right) [

42]. This situation implies that the viewpoint taking account of life-cycles and spatial flexibility, which were areas of interest in the 1960s and 1970s, cannot be accurately predicted in the rapidly changing contemporary society, and is gradually being excluded from consideration.

Therefore, “Public spaces are opened up by placing them parallel to the front yard. The border between the living room and its adjacent rooms can be expanded freely in order to respond to various family gatherings” [

43]. Most of the cases considering flexibility are aimed at controlling boundaries through responses to special events in the present situation, opening and closing for publicness and privacy or towards the surrounding view, and so on. Critics, however, are sometimes concerned that the tight and compact composition based on the present conditions of residents is “overtly grounded in reality” [

44].

4.1.4. The Desire for Different Unit and Various Housing Types

In the case of multi-unit housing projects, the desire to bring out the personality of residents leads to the desire for different units and various housing types. The existing housing type of apartments, which is based on the assumption that the universal nuclear family composed of couples and their children is an ideal model, has strictly limited consumer choice by being supplied in a uniform manner. Recently, we have been able to perceive efforts to explore various housing types in order to increase the choices of residents and to highlight their identity through housing, though this is limited as an active alternative.

The most common method was to combine the various units in a housing block. Thus, “Each of the units was tailor-made using the same space to yield different configurations to reflect the unique lifestyles of each family, combining three maisonettes and five apartment units” [

45]. Similarly, “Positioned around the staircase sitting at the center, the four units are duplexes making L, U and 11-shape in two and three dimensional ways, and they go up from the 1st floor to the 4th floor while making some combinations together” [

46]. In general, young architects often try “to evade the standard design structure of the multi-storey house by creating a variety of units in terms of their floor plans and sections, and to establish the composition of these units within the given volume. Recently, it has become possible to see more multi-storey houses, and even shared houses, which are made up of a tangled tetris-like composition of smaller different units” (

Figure 5, left) [

47]. This trend, which is emerging among Western architects, seems to have influenced domestic housing design. For instance, “The three studios each have different floor plans, which allowed them to be set at a higher price than that of the market value” (

Figure 5, right) [

48]. In such cases, differentiated units are linked to the demand for them, leading to economic profit.

However, only limited experiments are underway, such as creating a “unique shared space” or “collecting several types of units in one block”. There are hopeful signs, such as the report that observed, “The ‘duplex house’ styled by him has the potential to move in the pact of people who wish to establish their own homes with suitable resolutions. My only wish is that his upcoming projects do not coalesce into a uniform approach like that of the ‘Peanut House’ series (a once-popular form of duplex housing). From this aspect, this house is a point of departure, exhibiting the diverse potential of duplex housing. I believe it can act as inspiration for a new type of housing” [

31]. However, the availability of more viable housing alternatives that can move beyond apartments or position themselves competitively against them still remains poor.

4.2. The Relationship Between Individual and Family: The Structure for Communication

The treatment of the relationship between individual and family in lifestyle magazines is similar to that in architectural magazines.

4.2.1. The Interest in ‘Void’ Spaces Inside and Outside of the Buildings for Communication

In the case of architectural magazines, it was found out that they were actively paying attention to the “void” spaces inside and outside the building for their communication potential. The voids formed at the in-between spaces between separated masses or by removing a part of a mass at the point of contact between spaces of different characteristics, or the various inner and outer void spaces penetrating the masses vertically and horizontally, have always been noted as a space having various possibilities in terms of communication.

Communication in the open space between separated masses is the most commonly explored form of communication. Thus, “What most particularly caught my attention was the garden between the separated masses. It is expected to bring about communication, not only for the residents that use the private areas and the Daraewon (working area), but for the people living nearby who walk past the alley daily, and the neighbors facing the fence within the garden” [

49]. Similarly, “Suspended white masses will split, which makes a space that would create something new. This becomes an energy, which naturally results in a new community, which connects the owner and the tenants, houses and studios, horizontal and vertical, and big and small” [

50]. In the process of modernization, the existing Hanok (traditional Korean type of housing) structure composed of several houses around gardens was replaced with western style houses and apartments with centralized arrangements, combining functional and economic value with the desire for western-style living. There is now a strategy to divide and separate masses and to infiltrate various external spaces into masses again. For instance, “The open garden, which creates ‘horizontal penetration’ on the site, is the highlight of the house. (...) The ‘vertical penetration’ from the underground sunken garden to the dining room on the ground level, also serves as a topological window of communication through which the three generations and guests can meet” (

Figure 6, left) [

51]. Here, the outer void space penetrates the mass vertically and horizontally, creating an infrastructure of diverse communication.

This is also continuous with the inner void space formed through the various levels and walls. In contrast to outer voids that can be associated with neighbors or local residents, the inner void concentrates on family relationships. “The large central void in the living room is a key element that allows all members of the family to be within sight of one another” (

Figure 6, center) [

52]. Similarly, and “The 1st and 2nd floors are open, allowing for vertical communication. It also functions as a vertical intermediary space which refracts another view visible only from the second floor” [

41]. Thus, various types of void spaces may be inserted into the mass. A multi-floor type of void space helps to connect space flows between the 1st floor and 2nd floor. Thus, like in the case of “This house adopted ‘three types of void space’ in between five main rooms—the living room, master room, guest bedroom, parents’ room, and the children’s room. It can be understood as three types of contemporary Taechong Space (a main wooden-floored room in the Korean tradition), that is, as ‘a multi-floor type’, ‘an open type’, and ‘a variable type’” (

Figure 6, right) [

53]. For example, an open type is an open space between a guest bedroom and the kitchen. It can be used as an interior space using installed folding doors. In this regard, the architect named this project, “the Hanok 3.0 version”, emphasizing that it is a modern interpretation of Hanok’s space.

4.2.2. The Shared Spaces of Circulation as Social Places

In this case, shared spaces such as corridors, and stairs, which connect the rooms and levels, combined with various void spaces, are also attracting attention as new places that could have more functions beyond mere circulation.

An open stair becomes “the communication core of the house” [

34], and the stairway “connects this small place to live, which is made of a skipped floor” [

54]. As a device for securing the privacy of each member, and, at the same time, providing for communication between generations, spaces such as the urban alley are being actively introduced into the residential space. For example, “The void courtyard and its surrounding staircase are based on a 1.2–1.5 m width, a volume of 2 storeys, and a height that extends up to the roof. It does not show off its features but acts as a horizontal layer between divided domains. In fact, the corridor, staircase, and the courtyard divide the space between two generations, parents and children. It serves as the border between public and private spaces and yet also serves as a communication path” (

Figure 7, left) [

55].

The case below is also conscious of the function of the corridor as a space for communication, much like stairs: “At the end of the internal traffic line, which starts at the entrance, there is a master bedroom for a couple. (...) The opportunity to encounter and greet each other is naturally created when walking towards the space for the couple” (

Figure 7, right) [

55]. In other words, the various void spaces and the circulation spaces such as corridors and stairs around them have been recognized as social spaces that go beyond functional necessity to provide at an intersection of communication connecting living places.

4.2.3. The Weakened Social Function of Living Room

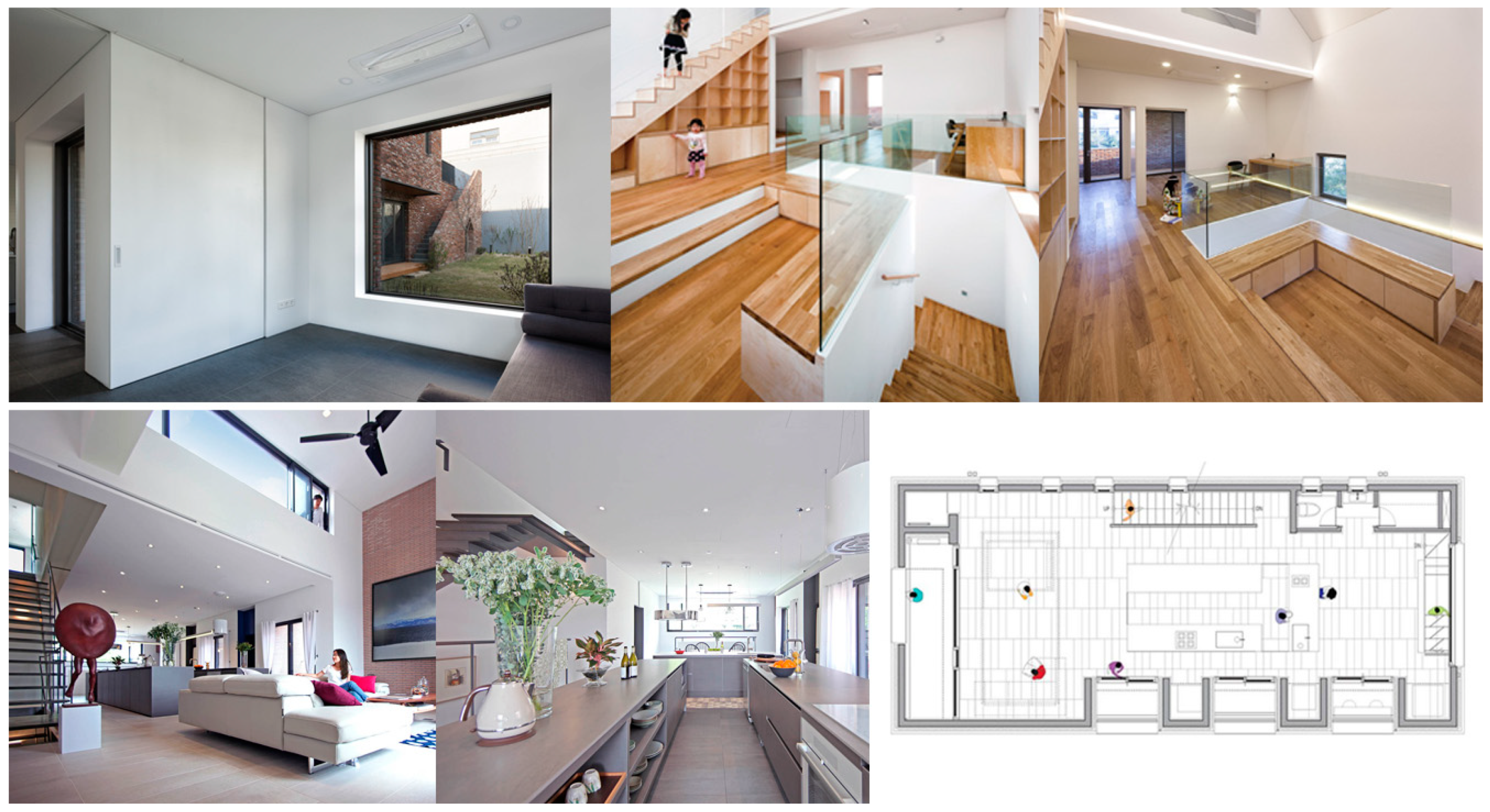

It is interesting to note that the social function of the living room, which is responsible for the communication and togetherness of the family, is dispersed and thus relatively weakened in the residential space. On the other hand, in the case of the kitchen, its position has become much higher in the context of communication. In other words, the kitchen has been given the duty to function as the center of the house and community, and integrates various social spaces spread all over the house.

The social function of the living room has been ascribed to the collection of common areas scattered throughout the house. For example, “While there is a TV and a mini sofa in the family space, it is somewhat of an ambiguous size to call it a full living room. (...) There is no room specifically designated as the living room in this house. There is no huge flat-screen TV, no speakers and long leather sofa facing the TV, as are commonly found in apartments. The small family space and the terrace café on the lower floor, and the u-shaped space and the attic on the upper floor act as the stage for all kinds of family activities” (

Figure 8, up) [

56]. On the other hand, the island kitchen is designed to be “the core of the house” (

Figure 8, down) [

57]. Further, “Preserving the angled corner of the site, the living room in which a console table is placed has no windows, making it private and intimate. (...) the dining room, in which a dining table that seats twelve has been placed, is connected to the entrance by a passageway and has an open view of the garden, playing a role similar to that of a reception room” [

42]. In addition, sometimes the first floor revolves around the kitchen. “This place is the brightest and warmest, becoming a place of gathering and communication for the family. (...) While the central structure of the kitchen and the dining room can be seen as such, programs that are needed in everyday life (study, family room, children’s playroom, laundry room, etc.) are concentrated on the floors below ground” [

43].

Another example observes that it was most important to face the family while working in the kitchen, and create “a situation which enables us to observe the children’s activity all the time” [

29]: “The kitchen is close to the junction of the two wings in the butterfly-shaped plan. I looked around when standing in front of the sink, as suggested by the client. I could see the garden and forest beyond the valley seen through the window. If you look up while cooking in the kitchen, you can enjoy the full panorama of nature. The kitchen has a good view of the living room, as it is two steps above the living room. The second floor also comes into sight through the staircase placed along the angle of folded wings. The wife, looking all around, stated ‘I can see every corner of the house from here. I can see my children playing under the stairs and even in the pool in the garden’” [

29].

Alongside these example, there also exists criticism of cases where spaces do not have a center, as in the following example: “However, the dining room space lacks a centripetal force to gather all family members together and also has a passive connectivity to the exterior. It is a reflection of the life of the owner, but it is a pity that there is not a new conceptual setting and exploration for the ‘eating space’ that is becoming more and more popular in the contemporary residential space” [

50].

4.2.4. The Intersection of ‘Sight’ for the Restoration of Relationship

In the context of communication, the most important sensual element is “sight.” In

Section 4.1, sight was a factor that enabled continuous and abundant architectural experience in a sequence of connected spaces with diverse individual characteristics. Now in

Section 4.2, the intersection of sight implies the restoration of the relationship. As in the following cases, “sight” is the most important factor in recognizing family togetherness: “The bridge, which is the heart of the space in this house, enables an exchange of glances on the first and second floor” (

Figure 9, left) [

36]. Similarly, “As a house for a large family, the balance between private areas and public spaces has been finely controlled. (...) Even if the floors separate the whole space, the architect tried to connect family members in each space with the possibility of eye contact between everyone” (

Figure 9, center) [

58]. In another case, “The inside is a bright white space and open to various views” [

59], and “Children enjoy spending time in the narrow corner under the stairs instead of in their rooms. Eye contact among family members, invisible in the plan, emerges in the 3D space. This connection makes them feel at ease, sensing each other” (

Figure 9, right) [

29]. Sometimes the architect aims for sight penetration to be able to extend beyond the boundary, so that the living space is communicated through the common internal and external spaces rather than a closed box. For instance, “I attempted to create a sense of visual communication and spatial expansion that would create connecting clues between the communicative space of living room, study, and yard, to each individual room, by penetrating the diagonal view and inserting an intermediate space system” [

60].

On the other hand, in modern apartments, visual exchanges with a person in the living room from one’s room can hardly be expected. Moreover, the windows all open to the outside. Therefore, it is as if to say, “Living in these kinds of housing with no internal relationship, your relationship with others easily turns into something called a root-tree system. I would like to connect the severed relationship through my works making it more like a rhizomatous relationship. My aim is to recover the exchange of views. The way to do it through architecture is by employing elements such as the courtyard, void spaces, or even windows. One features the client mentioned about the Mughakdong (another project of the architect) is how it allows you to view what your home looks like inside your home” [

61]. The gaze penetrating and crossing into the house is used as a means for restoring the inherent relationships between family members. Although fragmentary, a small window in the children’s room overlooking the kitchen provides opportunities for frequent exchanges of views [

61]. Similarly, “Thanks to the sharp shape of the house, with its acute and obtuse angles, the kitchen of this house became the focal point for the sights at various points in the house, much like a control tower can observe the taking off and landing of planes. (...) However, the client’s husband added the most impressive thing I heard when we had nearly finished the visit.” “The best thing is that this house created a space where my wife can see everything and my children can go everywhere” (

Figure 9, right) [

29]. Removing a part of the mass and inserting the void into the mass creates a space where, “What one would meet by crossing or going around the center of the house is ‘the view’ that is created by the endless movement from the staircases” [

62]. This kind of sight allows family members to recognize each other’s existence constantly and acts as the basis of various relationships that can be formed inside and outside the house.

4.2.5. The Interest in Spatial Cross-section through Various Levels

Interest in sight and visual communication naturally leads to interest in the cross-section, and the relationship between two-dimensional sights expands to the experiment to realize visual communication through various levels. The aspiration of communication penetrating through the vertical and horizontal voids leads to the interest in the spatial cross-section that is impossible in a flat apartment space with a homogeneous height. Thus, “The multi-level living room transforms the architectural spatial section that can’t be found in apartments or other detached houses, which allows communication between one another, the viewing of the nearby park, and reveals all three of the triangularly arranged windows, while the gable mass of the upper side is revealed through the narrow and high ceiling” [

38].

In addition, it sometimes tries to alleviate the difference of levels so as to make each space more closely related, by introducing a skip floor that maintains some degree of independence and the interconnection of spaces at the same time: “The section of the house follows the site’s natural contours, creating a split-level condition of half-levels. The result is a continuous experience of public, semi-public, and private spaces. (...) Meanwhile, a half-level up connects to a hovering mezzanine with a craft and play area that is visually connected to but private from the living areas directly below it” (

Figure 10, up) [

34]. Further, with such innovations as a glass floor on the second floor overlooking the entrance, the side window connecting the floor of the first-floor bedroom with the underground family room, and the rooftop looking down into a living room, this creates “a microscopic flow and continuity in the cross section and the house is filled with their spatial play” (

Figure 10, down) [

57].

These kinds of cross-sectional attempts also seek to build architectural vocabularies such as vertical gardens and public gardens by cracking the stacked structure of uniform spaces of the urban studio flat. This creates a new movement in the cross-section, and a new in-between space within the cityscape and community life. The open space formed through this method is “a place where one can experience nature and self-fulfillment, and also a space of possibility that opens up communication with the neighbors” [

63].

4.2.6. Open Plans and Flexibility with Soft Boundaries

Open plans and flexibility, which were often featured in lifestyle magazines, still constantly appear in architectural magazines. As in

Section 4.1, little attention has been given to flexibility as a response to the indeterminate future, while flexibility as a consideration of boundaries for communication frequently appears in architectural vocabularies: “The master bedroom is accessible only through the study and dress room, but when you open all the sliding doors, it becomes an open corridor surrounding the courtyard” [

55]. Similarly, “These directly connect to the landscape through large swing doors that erode the corners of the room” [

34]. In another case, “At that time, the mother of the sisters had opened the folding window fully, turning the room into a semi-outdoor space. This place was named as the AV room on the floor plan, but it felt unfitting. One can tell that the furniture, furnishings, and the density of the atmosphere were focused primarily onto family activities” (

Figure 11, left) [

56]. Thus, flexibility can be understood as the control of boundaries for various kinds of communication inside the space or at the interface of the inside and the outside.

The reason flexibility and the open plan are interpreted as structures for communication is that the wall is understood as a symbol of disconnection. The desire for an open collective space with ambiguous characteristics of public and private spaces is often reflected, rather than for housing as a clear separation of public and private spaces. For this, “The living room, library, and the kitchen on the second floor are part of the ‘family room’, and are not separated by walls, but by wooden crossbeams on the ceiling” (

Figure 11, center) [

37]. There is also an attempt to revive the archetype of Dutch Structuralist architecture because, “Recognizing the broken family of contemporary society as a broken wall, these methods are intended to revive the structuralism of architecture, recreating the spatial structure to restore human relationships, which, in turn, restores family communication through the transformation of the wall” (

Figure 11, right) [

60].

The important point is not the introduction of a multi-purpose space that is simply open and large like the open-plan that was popular in the mid-1900s. Rather, contemporary plans try to introduce a space that has a certain atmosphere in itself and can be constantly newly interpreted by adjusting the relationship with a private or adjacent space. That is, it is required to search for new boundaries with the potential for separation and expansion of various spaces through a soft and flexible interface.

5. Conclusions

This study attempted to analyze the gap between the uniform and monotonous lifestyles in existing apartments and the changed lifestyle of the present age. In addition, it explored the characteristics of residential spaces serving newly emerging lifestyles, focusing on the aspects of “the characteristics of residents” and “the relationship between individual and family.” To do so, we compared the ways in which domestic urban housing was approached in lifestyle magazines aimed at the general public and in architectural magazines aimed at architectural experts. Through this, it was possible to understand the changed lifestyles of residents, and the characteristics of residential spaces in reflecting these changes.

With regard to “the characteristics of residents”, the existing universal concept of residents did not work any longer in lifestyle magazines, and a new concept of residents with diverse and multi-layered characteristics emerged. In particular, most of those featured in lifestyle magazines are engaged in creative occupations, encompassing a wide range of professions. Rather than emphasizing their position in the company, they are more interested in positively revealing the contents and interests of their work and constantly pursuing their personality and identity through professional hobbies. Such individuals want to possess cultural capital by experimenting with and incorporating diverse and heterogeneous cultures, rather than a single high culture symbolizing a uniform fashion or class identity, because the representative characteristic of creativity is openness. The household composition has also expanded to the extent that it cannot be integrated into the existing universal nuclear family. This means that the characteristics of each member and the contents of their lives have been expanded in ways that make them difficult to predict as before.

However, in architectural magazines, specific references to residents and lifestyles were found to be limited, and attempts to capture the individual characteristics of residents focused primarily on the architectural plasticity of the exterior. Critics, however, have questioned architectural plasticity, resulting from a collaboration between the client’s desires for boasting and architect’s desires of achievement. Instead, they have favorably evaluated attempts at developing the differentiated spatial diversity of each room beyond the homogeneous arrangement of apartments. In addition, in the case of collective housing, it was found that the attempt to reflect the characteristics of residents leads to a desire for various housing types beyond apartments and for differentiated units of housing.

With regards to “the relationship between individual and family”, existing housing clearly divides each room and seeks functional differentiation with internalization, reduction of social space, and individualism. However, we found that it is possible to find a tendency in contemporary lifestyle magazines toward soft and flexible boundaries as a means to pursue the feeling of family togetherness by sensing each other’s existence. The desire for the sweet home of the average nuclear family, which emerged with modernism, has now been strengthened through a focus on family-community rather than individual privacy and independence. This is because the relationship between family members has become more intimate and equal, in the pursuit of real happiness and value of life. This kind of family-community, unlike the earlier type, shows the characteristics of a flexible community of contemporary society, which emphasizes communication alongside the respect of individual identity and freedom. Spatial solutions in this regard have mainly come in the form of open plans, sliding doors, transparency through the use of glass doors and windows, and the use of public spaces such as corridors and stairs as social spaces in lifestyle magazines.

These characteristics appears in a similar fashion in architectural magazines. The void space that penetrates both the inside and outside of the building horizontally and vertically has been noted as a space with various possibilities, especially in terms of communication. In addition, shared spaces combined with various void spaces are considered as new spaces for communication, and are given more programs beyond the function of circulation. In this process, the social function of the living room has been reduced and its status has been relatively weakened, while the kitchen is an area of growing importance in the context of communication. In addition, the sensory element that is the most important for communication was “sight”, and the micro-society in which family members live together is worked out in detail through the eyes. The interest in sight and various forms of visual communication leads naturally to the interest in the cross-section of spaces beyond the uniform height of apartments. The open plan, flexibility, and transparency are the factors that constantly appeared as the structures for communication, as in the lifestyle magazines. Architectural magazines also understand the wall as a symbol of disconnection and try to restore family relationships through structures of communication created by transforming the wall.

The truth that was confronted consistently in the process of analyzing the characteristics of the changed lifestyles and residential spaces was the limit of existing spaces of apartments and the desire to overcome it. Creating a correspondence between residential spaces and forms of lifestyles is a basic requirement for sustainable housing. Thus, the designing of residential spaces will have to start with serious research into the nature of residents and their lifestyles, supplemented by an exploration of the characteristics of residential spaces that can support them.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “conceptualization, H.K. and S.K.; methodology, H.K.; software, S.K.; validation, H.K. and S.K.; formal analysis, H.K.; investigation, H.K.; resources, S.K.; data curation, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, H.K. and S.K.; visualization, H.K.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, H.K. and S.K.; funding acquisition, H.K. and S.K.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (No. 2015R1D1A1A01057353), and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2016R1C1B1013955).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Park, H. The Game of Apartments; Humanist: Seoul, Korea, 2014; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- KOSIS (Korean Statistical Information Service). 2010. Available online: www.kosis.kr (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Lim, D.; Kim, J. The Birth of Metropolis Seoul; Banbibooks: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 196–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, S. Variation in the Characteristics of Everyday Life and Meaning of Urban Housing Due to the Transition of Social Structure: Focusing on Articles Published in Lifestyle Magazines. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelezeau, V. Seoul, Ville Geante, Cites Radieuses; Kill, H., Translator; Fumanitas: Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, J.; Olsson, A.R. Sustainable Stockholm: Exploring Urban Sustainability in Europe’s Greenest City; Routledge Books: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 71–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, G. A Study on the Alienation of Everyday Life in Korean Apartment Complexes: Focused on Reduced Boundary of Everyday Life in the Area of Production and Supply. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2012, 28, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H. A Study on the Alienation of Everyday Life in Korean Apartment from the Perspective of Consumption and Demand. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2014, 30, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, N. Space History of Korean Housing; Dolbegae: Paju, Korea, 2010; p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- KOSIS (Korean Statistical Information Service). 1985 & 1995. Available online: www.kosis.kr (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Park, C.; Park, I. House in Exchange for Apartment; Dongnyok Press: Paju, Korea, 2011; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- King, P. A Social Philosophy of Housing; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2003; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S. Crazy about Apartments; Esoope: Seoul, Korea, 2010; pp. 123, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C. Cultural History of Apartments; Sallim: Paju, Korea, 2006; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, N.; Yang, S.; Hong, H. Microhistory of Korean Housing; Dolbegae: Paju, Korea, 2009; pp. 176, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Claire Korea. My little universe. Maison, 31 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Claire Korea. An Apartment with unique furniture layout. Maison, 3 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, N. Reevaluation of Modernization in Korean Housing Culture since 1980. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2014, 22, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H. A Study on the Relationship between Commodification, and Everyday Life in Korean Urban Housing. Ph.D. Dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, August 2012; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Design House. I go to the home-office. House Full of Happiness, 31 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Media Group. We are together again. Living Sense, 30 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Media Group. Wide house. Living Sense, 28 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Media Group. Unjung-dong Dormitory for the morning of three sisters. Living Sense, 31 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J. Unfamiliar harmony. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. Urban Housing in Northeast Asia: The search for alternatives. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. 549-1 Pangyo-dong. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. 876 Unjung-dong. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. 878-4 Unjung-dong. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S. Reason of a form. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2017; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Built Environment correspondence with architecture. In Space; Space Magazine; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, June 2015; pp. 94–95. [Google Scholar]

- Min, W. Lenience and ambiguity. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S. Outside of architecture. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2017; pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, W. Popular courtyard housing. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- John, H. Tacit struggle: Converging architectural experience and sustainable strategies. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2017; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. The box opening. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W. Fiction and non-fiction: The art of architectural storytelling. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2017; pp. 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. Realistic architecture. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, E. Memories of home and evolution. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Y. Scenery that fills the ‘domain of the gap’. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. The starting point of a somewhat ‘unfamiliar’ change. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J. Dugu-dong House I. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2017; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K. Between public demand and private programmes. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C. A concave wall, abundant sensitive perceptions. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S. Gurem Jeongwon Housing Coop. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Joh, S. ‘Balcony expansion’ is for an expanding balcony, not for interior space. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2017; pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Nonhyun-dong multi-storey house: Air Multi-storey. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2017; pp. 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C. DARAK DARAK neighbourhood living facility. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. Reinterpretation of the hometown scenery. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S. Inter-White. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2016; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J. The challenge and conquest of topology. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. Go-Gae Jip. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, H. Hanok 3.0. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S. Spacing and the future ahead. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S. A continuum of undivided corridors. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y. Coconut house. In Space; CNB Media: Seoul, Korea, November 2017; p. 72. [Google Scholar]