Biting the Bullet: Dealing with the Annual Hunger Gap in the Alaotra, Madagascar

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

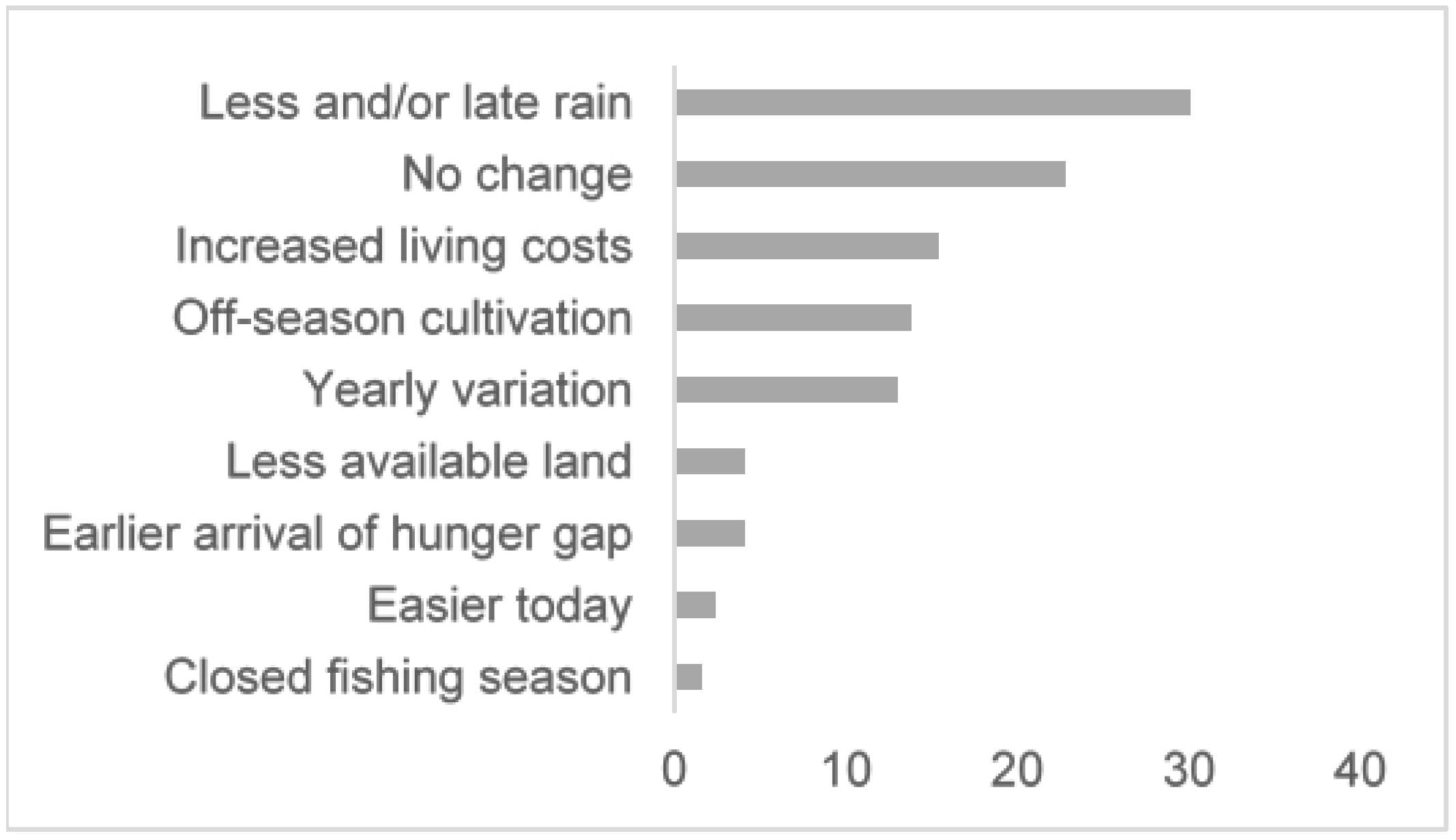

3.1. Resource and Climate Dynamics Surrounding Lake Alaotra

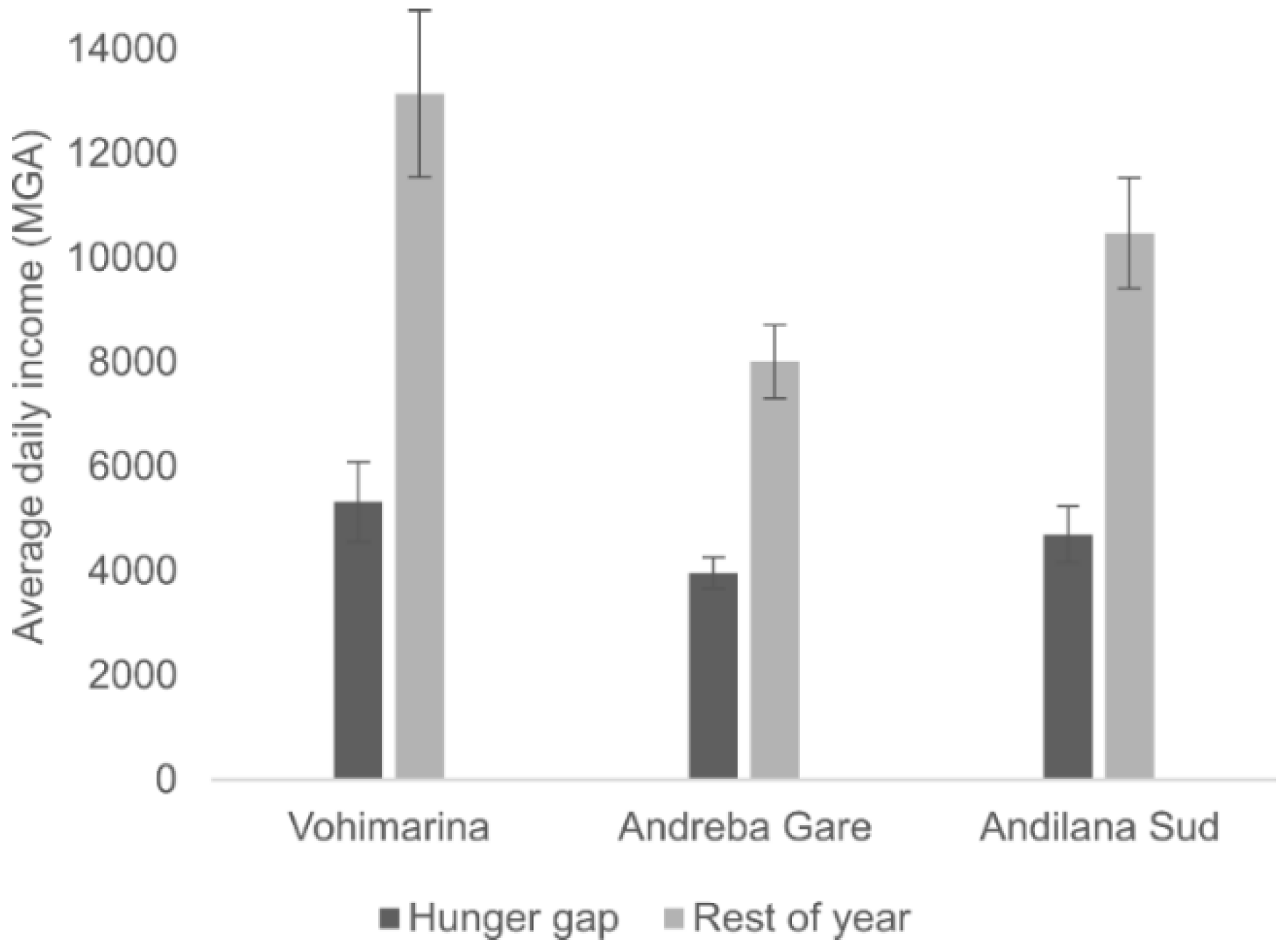

3.2. Perceived Impacts of the Hunger Gap

3.3. Coping with the Hunger Gap

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Participant Demographics

| Vohimarina | Andreba Gare | Andilana Sud | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % female | 65.9 | 42.9 | 51.2 | 53.3 |

| mean age | 39.4 (12.4) | 40.1 (13.0) | 44.3 (12.3) | 41.3 |

| mean years of education | 7.6 (2.5) | 6.3 (3.1) | 8.5 (2.5) | 7.5 |

| household size | 4.8 (2.0) | 4.8 (2.0) | 4.6 (1.5) | 4.7 |

| % land owners | 85.4 | 61 | 92.68 | 79.7 |

Appendix B. Interview Questions

- Fokontany:

- Date:

- Participant number:

- Introduction

- We are conducting this study as part of the Alaotra Resilient Landscape (AlaReLa) project, based in Ambatondrazaka. We are trying to better understand farmers’ and fishers’ experience of the hunger gap around lake Alaotra. Everything that we discuss is confidential, and your responses will remain anonymous. Do you agree to continue with the interview?

- Personal details

- Sex

- How old are you?

- Where were you born?

- If not in the Alaotra region, ask when and why they moved to the region.

- Are you married?

- What is your main occupation?

- What are your secondary or tertiary occupation(s)?

- How many years of schooling did you have?

- How many people life in your household?

- How many children do you have?

- If yes ask how old the children areIf yes ask whether the children go to school

- How much do you earn during an average day?

- Physical wealth

- Are you a:

- Land owner

- If yes, ask more details about how much and where

- Land tenant

- Daily labour

- Other (please specify)

- Do you own livestock?

- If yes, ask what kind and how many.

- Agriculture

- What crops do you grow and where?

- What do you do with your crops?

- Ask how much they keep for their own consumption and how much they sell.

- What do you do with the money you earn from selling produce or from your other activities?

- Hunger gap

- What is your understanding and experience of the hunger gap?

- What impacts does the hunger gap have for you personally?

- What do you do to try to reduce these impacts?

- Has the hunger gap changed during the last 10 years?

- If yes, ask how, when and why

- How does your income vary during the year?

- Ask about income and expenses during the hunger gap and the rest of the year

- Are you pushed towards new activities during the hunger gap?

- If yes, ask what activities and why

- What are your eating habits like during the hunger gap compared to the rest of the year?

- Ask about type of food, quantity, quality

- Finance

- Do you or have you ever used microfinancing?

- If yes, why and when, and their experience of using microfinancingIf no, ask why

- Do you think that microfinancing could help with the hunger gap?

- How do you organise your children’s schooling fees during the hunger gap?

- Closing question

- What do you think could be done by yourself personally, by the community, or by the government, to decrease the impacts of the hunger gap?

References

- Gill, G.J. Seasonality and Agriculture in the Developing World: A Problem of the Poor and Powerless; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, S.; Sabates-Wheeler, R.; Longhurst, R. Seasonality, Rural Livelihoods, and Development; Earthscan: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chiwaula, L.; Waibel, H. Does seasonal vulnerability to poverty matter? A case study from the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands in Nigeria. In Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Berlin, Germany, 24–25 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselberg, J.; Yaro, J.A. An assessment of the extent and causes of food insecurity in northern Ghana using a livelihood vulnerability framework. GeoJournal 2006, 67, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S.; Mahmud, W. Mitigating seasonal hunger: Evidence from Northwest Bangladesh. In Policy Brief, International Growth Centre (IGC); LSE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, S.H.; Hadley, S.; Cichon, B. Crisis behind closed doors: Global food crisis and local hunger. J. Agrar. Chang. 2010, 10, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Quinn, T.; Lorenzoni, I.; Murphy, C.; Sweeney, J. Changing social contracts in climate-change adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotoks, A.; Kuhnert, M.; Dawson, T.P.; Smith, P. Global hotspots of conflict risk between food security and biodiversity conservation. Land 2017, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.K.; Belghith, N.B.H.; Bi, C.; Thiebaud, A.; Mcbride, L.; Jodlowski, M.C. Shifting Fortunes and Enduring Poverty in Madagascar: Recent Findings; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Waeber, P.O.; Wilmé, L.; Mercier, J.-R.; Camara, C.; Lowry, P.P., II. How effective have thirty years of internationally driven conservation and development efforts been in Madagascar? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSTAT (Institut National de la Statistique). Madagascar Millennium Development Goals National Monitoring Survey; INSTAT: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The MDG Country Progress Snapshot: Madagascar; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). FAOSTAT: Madagascar; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, C.A.; Rakotobe, Z.L.; Rao, N.S.; Dave, R.; Razafimahatratra, H.; Rabarijohn, R.H.; Rajaofara, H.; MacKinnon, J.L. Extreme vulnerability of smallholder farmers to agricultural risks and climate change in Madagascar. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2014, 369, 20130089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotobe, Z.L.; Harvey, C.A.; Rao, N.S.; Dave, R.; Rakotondravelo, J.C.; Randrianarisoa, J.; Ramanahadray, S.; Andriambolantsoa, R.; Razafimahatratra, H.; Rabarijohn, R.H.; et al. Strategies of smallholder farmers for coping with the impacts of cyclones: A case study from Madagascar. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 2016, 17, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, A.R.; Mittermeier, G.C.; da Fonseca, B.G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Parks, K.E.; Bethell, C.A.; Johnson, S.E.; Mulligan, M. Predicting plant diversity patterns in Madagascar: Understanding the effects of climate and land cover change in a biodiversity hotspot. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitla, B.; Devereux, S.; Swan, S.H. Seasonal hunger: A neglected problem with proven solutions. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S.R.; Khalily, M.A.B.; Samad, H.A. Seasonal and extreme poverty in Bangladesh: Evaluating an ultra-poor microfinance project. In Policy Research Working Paper No. WPS 5441; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, G.; Chowdhury, S.; Mobarak, A.M. Escaping famine through seasonal migration. In Yale Economics Department Working Paper 124; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Copsey, J.A.; Rajaonarison, L.H.; Randriamihamina, R.; Rakotoniaina, L.J. Voices from the marsh: Livelihood concerns of fishers and rice cultivators in the Alaotra wetland. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2009, 4, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, L.; Mietton, M.; Robison, L.; Erismann, J. Lake Alaotra—Past, present and future. Ann. Geomorphol. 2009, 53, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSTAT (Institut National de la Statistique). Available online: http://www.instat.mg/ (accessed on 29 December 2016).

- Stoudmann, N.; Waeber, P.O.; Randriamalala, I.H.; Garcia, C. Perception of change: Narratives and strategies of farmers in Madagascar. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 56, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direction Régional des Ressources Halieutiques et de la Pêche (DRRHP) Alaotra Mangoro. Development of the fish catches from the Lac Alaotra, edited by DRRHP, Unpublished raw data gathered through personal communication. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Andrianandrasana, H.T.; Randriamahefasoa, J.; Lewis, R.E.; Ratsimbazafy, J.H. Participatory ecological monitoring of the Alaotra wetlands in Madagascar. Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 2757–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, L. Rice on Shares: Agrarian Change and the Development of Sharecropping in Alaotra, Madagascar. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, L. Women as rice sharecroppers in Madagascar. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1991, 4, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendigs, A.; Reibelt, L.M.; Ralainasolo, F.B.; Ratsimbazafy, J.H.; Waeber, P.O. Ten years into the marshes—Hapalemur alaotrensis conservation, one step forward and two steps back? Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2015, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotoarisoa, J.; Bélières, J.-F.; Salgado, P. (Eds.) Agricultural Intensification in Madagascar: Public Policies and Pathways of Farmers in the Vakinankaratra Region. PROIntensAfrica. 2016. Available online: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/582242/1/ProIA_IDCS%20Madagascar_final%20report.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- Bellemare, M.F. Sharecropping, insecure land rights and land titling policies: A case study of Lac Alaotra, Madagascar. Dev. Policy Rev. 2009, 27, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibelt, L.M.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Waeber, P.O. Lac Alaotra bamboo lemur Hapalemur alaotrensis (Rumpler, 1975). In Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018; Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Eds.; IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG); International Primatological Society (IPS); Conservation International (CI); Bristol Zoological Society: Arlington, VA, USA, 2017; pp. 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Waeber, P.O.; de Grave, A.; Wilmé, L.; Garcia, C.A. Play, learn, explore: Grasping complexity through gaming and photography. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeber, P.O.; Reibelt, L.M.; Randriamalala, I.H.; Moser, G.; Raveloarimalala, L.M.; Ralainasolo, F.B.; Ratimbazafy, H.; Woolaver, L. Local awareness and perceptions: Consequences for conservation of marsh habitat at Lake Alaotra for one of the world’s rarest lemurs. Oryx 2018, 52, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, L.; Mietton, M.; Touchart, L.; Hamerlynck, O. Lake Alaotra (Madagascar) is not about to disappear. Hydrological and sediment dynamics of an environmentally and socio-economically vital wetland. Dyn. Environ. 2013, 32, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mietton, M.; Gunnell, Y.; Nicoud, G.; Ferry, L.; Razafimahefa, R.; Grandjean, P. ‘Lake’Alaotra, Madagascar: A late Quaternary wetland regulated by the tectonic regime. CATENA 2018, 165, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, P.L.; Richter, T.; Waeber, P.O.; Mantilla-Contreras, J. Lake Alaotra wetlands: How long can Madagascar’s most important rice and fish production region withstand the anthropogenic pressure? Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2015, 10, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, M.; Toit, D.D.; Pollard, S. ARDI: A co-construction method for participatory modelling in natural resources management. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibelt, L.M.; Moser, G.; Drey, A.; Randriamalala, I.H.; Chamagne, J.; Ramamonjisoa, B.; Garcia-Barrios, L.; Garcia, C.A.; Waeber, P.O. Tool development to understand rural resource users’ land use and impacts on land type changes in Madagascar. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. Br. Med. J. 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, M. Framework for Climate-Based Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment in Mountain Areas; International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmé, L.; Waeber, P.O.; Mouton, F.; Gardner, C.; Razafindratsima, O.; Sparks, J.J.; Kull, C.A.; Ferguson, B.; Lourenço, W.R.; Jenkins, P.D.; et al. A proposal for ethical conduct in research in and on Madagascar. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2016, 11, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, A.; Mitchell, T.; Lewis, K.; Lenhardt, A.J.; Lindsey, S.L.; Muir-Wood, R. The Geography of Poverty, Disasters and Climate Extremes in 2030; ODI: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rakotosamimanana, V.R.; Arvisenet, G.; Valentin, D. Studying the nutritional beliefs and food practices of Malagasy school children parents. A contribution to the understanding of malnutrition in Madagascar. Appetite 2014, 81, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.P.C.; Jones, J.P.G.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Wallace, G.E.; Young, R.; Nicholson, E. Drivers of the distribution of fisher efforts at Lake Alaotra, Madagascar. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 44, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.P.C.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Jones, J.P.G.; Bunnefeld, N.; Young, R.; Nicholson, E. Quantifying the short-term costs of conservation interventions for fishers at Lake Alaotra, Madagascar. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0129440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibelt, L.M.; Waeber, P.O. Approaching human dimensions in lemur conservation at Lake Alaotra, Madagascar; Intech Open: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.; Fordham, M. Double disaster: Disaster through a gender lens. In Hazards, Risks, and Disaster in Society; Collins, A.E., Samantha, J., Manyena, B., Jayawickrama, J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Penot, E.; Benz, H.; Bar, M. Utilisation d’indicateurs économiques pertinents pour l’évaluation des systèmes de production agricoles en termes de résilience, vulnérabilité et durabilité: Le cas de la région du la Alaotra à Madagascar. Ethics Econ. 2014, 11, 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Minten, B.; Randrianarisoa, J.-C.; Barrett, C.B. Productivity in Malagasy rice systems: Wealth-differentiated constraints and priorities. Agric. Econ. 2007, 37, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratsimbazafy, J.H.; Ralainasolo, F.B.; Rendigs, A.; Mantilla-Contreras, J.; Andrianandrasana, H.; Mandimbihasina, A.G.; Nievergelt, C.M.; Lewis, R.; Waeber, P.O. Gone in a puff of smoke? Hapalemur alaotrensis at great risk of extinction. Lemur News 2013, 17, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Reibelt, L.M.; Stoudmann, N.; Waeber, P.O. A role-playing game to learn and exchange about real-life issues. In Learn2Change—Transforming the World through Education; Verein Niedersächsischer Bildungsinitiativen (VNB e.V.): Hanover, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Urech, Z.L.; Zaehringer, J.G.; Rickenbach, O.; Sorg, J.-P.; Felber, H.R. Understanding deforestation and forest fragmentation from a livelihood perspective. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2015, 10, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibelt, L.M.; Woolaver, L.; Moser, G.; Randriamalala, I.H.; Raveloarimalala, L.M.; Ralainasolo, F.B.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Waeber, P.O. Contact matters—Local people’s perceptions of Hapalemur alaotrensis and implications for conservation. Int. J. Primatol. 2017, 38, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Madagascar: Systematic Country Diagnostic; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.L. Microcredit and agriculture: Challenges, success and prospects. In Microfinance in Developing Countries; Gueyie, J.-P., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillen: Basingstoke, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R.; Musshoff, O. Can flexible microfinance loans improve credit access for farmers? Agric. Financ. Rev. 2013, 73, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, E.; Wampfler, B.; Ralison, E. Rice inventory credit in Madagascar: Conditions of access and diversity of rationales around a hybrid financial and marketing service. In Rural Microfinance and Employment (RuMe) Working Paper; RUME: Marseille, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooyen, C.; Stewart, R.S.; de Wet, T. The impact of microfinance in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of the evidence. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2249–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minten, B.; Barrett, C.B. Agricultural technology, productivity, and poverty in Madagascar. World Dev. 2008, 36, 797–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, C.; Mulder, M.B.; Fitzherbert, E. Seasonal food insecurity and perceived social support in rural Tanzania. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, H.; Nin-Pratt, A.; Diao, X. Mechanization and agricultural technology evolution, agricultural intensification in Sub-Saharan Africa: Typology of agricultural mechanization in Nigeria. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 95, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penot, É.; Dabat, M.H.; Rakotoarimanana, A.; Grandjean, P. L’évolution des pratiques agricoles au lac Alaotra à Madagascar. Une approche par les temporalités. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environn. 2014, 18, 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto, Y.; Horie, T.; Randriamihary, H.; Shiraiwa, T.; Homma, K. Soil management: The key factors for higher productivity in the fields utilizing the system of rice intensification (SRI) in the central highlands of Madagascar. Agric. Syst. 2009, 100, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, D. The System of Rice Intensification: Time for an empirical turn. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2011, 57, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serpantié, G.; Rakotondramanan, M. From standards to practices: The Intensive and Improved Rice Systems (SRI and SRA) in the Madagascar highlands. In Challenges and Opportunities for Agricultural Intensification of the Humid Highland Systems of Sub-Saharan Africa; Vanlauwe, B., van Asten, P., Blomme, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, A.J.; Hobbs, P.R.; Riha, S.J. Stubborn facts: Still no evidence that the System of Rice Intensification out-yields best management practices (BMPs) beyond Madagascar. Field Crops Res. 2008, 108, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, E.; Glover, D.; Kuyvenhoven, A. On-farm impact of the System of Rice Intensification (SRI): Evidence and knowledge gaps. Agric. Syst. 2015, 132, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penot, E.; Fevre, V.; Flodrops, P.; Razafimahatratra, H.M. Conservation Agriculture to buffer and alleviate the impact of climatic variations in Madagascar: Farmers’ perception. Cahiers Agric. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruelle, G.; Naudin, K.; Scopel, E.; Domas, R.; Rabeharisoa, L.; Tittonell, P. Short- to mid- term impact of conservation agriculture on yield variability of upland rice: Ecidence from farmer’s fields in Madagascar. Exp. Agric. 2015, 51, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudin, K.; Bruelle, G.; Salgado, P.; Penot, E.; Scopel, E.; Lubbers, M.; de Ridder, N.; Giller, K.E. Trade-offs around the use of biomass for livestock feed and soil cover in dairy farms in the Alaotra lake region of Madagascar. Agric. Syst. 2014, 134, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgerson, C.; Vonona, M.A.; Vonona, T.; Anjaranirina, E.J.G.; Lewis, R.; Ralainasolo, F.; Golden, C.D. An evaluation of the interactions among household economies, human health, and wildlife hunting in the Lac Alaotra wetland complex of Madagascar. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: The science of natural resource management for poor farmers in marginal environments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 93, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; D’Annolfo, R.; Graeub, B.E.; Cunningham, S.A.; Breeze, T.D. Farming approaches for greater biodiversity, livelihoods, and food security. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-Benz, H.; Rakotoson, J.; Rasolofo, P. Les Politiques de Stabilisation des prix du riz à Madagascar; AFD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de l’Agriculture. Stratégie Nationale de Mécanisation de la Filière de riz à Madagascar; Ministère de l’Agriculture: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2015.

- Rakotosamimanana, V.R.; Valentin, D.; Arvisenet, G. How to use local resources to fight malnutrition in Madagascar? A study combining a survey and a consumer test. Appetite 2015, 95, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, C.M.; Connors, M.M.; Sobal, J.; Bisogni, C.A. Sandwiching it in: Spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate income urban households. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibelt, L.M.; Richter, T.; Waeber, P.O.; Rakotoarimanana, S.; Mantilla-Contreras, J. Environmental education in its infancy at Lake Alaotra, Madagascar. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2014, 9, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, J.R. The impact of health and nutrition on education. World Bank Res. Obs. 1996, 11, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; Pollitt, E. Malnutrition, poverty and intellectual development. Sci. Am. 1996, 274, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.P.; Wachs, T.D.; Gardner, J.M.; Lozoff, B.; Wasserman, G.A.; Pollitt, E.; Carter, J.A. Child development: Risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet 2007, 369, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Bertlett, K.; Gowani, S.; Merali, R. Is Everybody Ready? Readiness, Transition and Continuity: Lessons, Reflections and Moving Forward. Paper Commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2007. Strong Foundations: Early Childhood Care and Education. 2006. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000147441 (accessed on 9 April 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoudmann, N.; Reibelt, L.M.; Kull, C.A.; Garcia, C.A.; Randriamalala, M.; Waeber, P.O. Biting the Bullet: Dealing with the Annual Hunger Gap in the Alaotra, Madagascar. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072147

Stoudmann N, Reibelt LM, Kull CA, Garcia CA, Randriamalala M, Waeber PO. Biting the Bullet: Dealing with the Annual Hunger Gap in the Alaotra, Madagascar. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072147

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoudmann, Natasha, Lena M. Reibelt, Christian A. Kull, Claude A. Garcia, Mirana Randriamalala, and Patrick O. Waeber. 2019. "Biting the Bullet: Dealing with the Annual Hunger Gap in the Alaotra, Madagascar" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072147