Students’ Perception of Using Digital Badges in Blended Learning Classrooms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

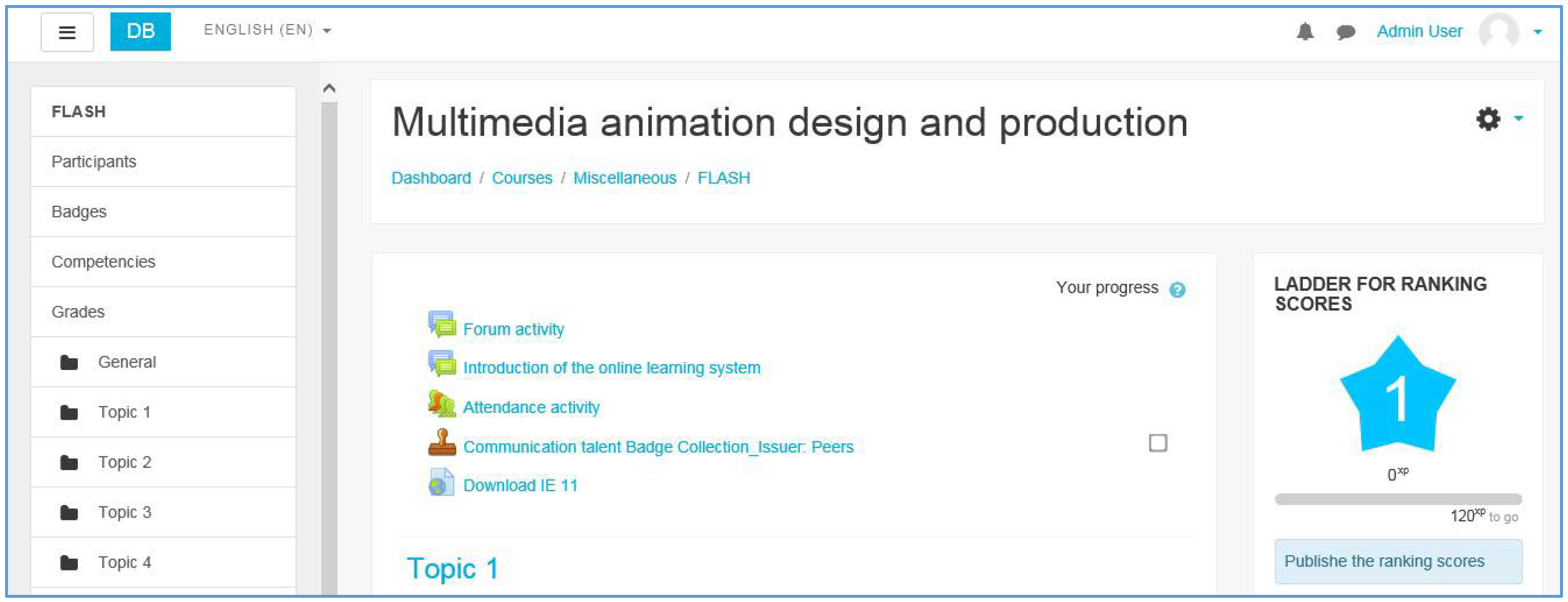

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Reward Mechanisms and Digital Badges in Education

2.2. Blended Learning in Higher Education

2.3. Digital Badges as Game Mechanics in Moodle Learning Platform

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Q Methodology for Analyzing Students’ Perception

3.2. Context

3.3. Participants

3.4. Instrument

3.5. Procedure

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Student’s Perception of the Digital Badges Mechanism

5.1.2. Effect of a Digital Badges Mechanism on Blended Learning

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, D.; Huang, R.; Wosinski, M. Future Trends of Smart Learning: Chinese Perspective. In Smart Learning in Smart Cities. Lecture Notes in Educational Technology; Liu, D., Huang, R., Wosinski, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 185–215. [Google Scholar]

- Halverson, L.R.; Spring, K.J.; Huyett, S.; Henrie, C.R.; Graham, C.R. Blended learning research in higher education and K-12 settings. In Learning, Design and Technology; Michael, J.S., Barbara, B.L., Marcus, D.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.R. Blended learning systems. In The Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs; Bonk, C.J., Graham, C.R., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, N.B.; Hull, A.L.; Young, J.B.; Stoller, J.K. Just imagine: New paradigms for medical education. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, J.; Devedzic, V. Open badges: Novel means to motivate, scaffold and recognize learning. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2015, 20, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, L.E.; Nunn, S.G.; Avella, J.T. Digital Badges and Micro-credentials: Historical Overview, Motivational Aspects, Issues, and Challenges. In Foundation of Digital Badges and Micro-Credentials; Ifenthaler, D., Bellin-Mularski, N., Mah, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Filsecker, M.; Hickey, D.T. A multilevel analysis of the effects of external rewards on elementary students’ motivation, engagement and learning in an educational game. Comput. Educ. 2014, 75, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boticki, I.; Baksa, J.; Seow, P.; Looi, C.K. Usage of a mobile social learning platform with virtual badges in a primary school. Comput. Educ. 2015, 86, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Singh, S. Digital badges in afterschool learning: Documenting the perspectives and experiences of students and educators. Comput. Educ. 2015, 88, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, W.M.; Hope, S.; Adams, B. Teachers’ perceptions of digital badges as recognition of professional development. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, R.; Porto, S.; Thompson, J. Competency-based education and the relationship to digital badge. In Digital Badges in Education: Trends, Issues and Cases; Muilenburg, L.Y., Berge, Z.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovich, S. Understanding digital badges in higher education through assessment. Horizon 2016, 24, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.; Pierce, W.D.; Banko, K.M.; Gear, A. Achievement-Based Rewards and Intrinsic Motivation: A Test of Cognitive Mediators. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.; Ostashewski, N.; Flintoff, K.; Grant, S.; Knight, E. Digital badges in education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2013, 20, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyjur, P.; Lindstrom, G. Perceptions and uses of digital badges for professional learning development in higher education. TechTrends 2017, 61, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovich, S.; Schunn, C.; Higashi, R.M. Are badges useful in education? It depends upon the type of badge and expertise of learner. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2013, 61, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Potential and Value of Using Badges for Adult Learners. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/about-shrm/news-about-shrm/Documents/AIR_Digital_Badge_Report_508.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Hanus, M.D.; Fox, J. Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchem, I. Digital Badges at (Parts of) Digital Portfolios: Design Patterns for Educational and Personal Learning Practice. In Foundation of Digital Badges and Micro-Credentials; Ifenthaler, D., Bellin-Mularski, N., Mah, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 343–368. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovich, S.; Wardrip, P. Impact of Badges on Motivation to Learn. In Digital Badges in Education: Trends, Issues and Cases; Muilenburg, L.Y., Berge, Z.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, K.L.; Stefaniak, J.E. An exploration of the utility of digital badging in higher education settings. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 66, 1211–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, K.F.; Huang, B.; Chu, K.W.S.; Chiu, D.K. Engaging Asian students through game mechanics: Findings from two experiment studies. Comput. Educ. 2016, 92, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.L. History and Context of Open Digital Badges. In Digital Badges in Education: Trends, Issues, and Cases; Muilenburg, L.Y., Berge, Z.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Biles, M.L.; Plass, J.L. Good Badges, Evil Badges? Impact of Badge Design on Learning from Games. In Digital Badges in Education: Trends, Issues, and Cases; Muilenburg, L.Y., Berge, Z.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, J.M. Blended Learning Design: Five Key Ingredients. Available online: https://www.it.iitb.ac.in/~s1000brains/rswork/dokuwiki/media/5_ingredientsofblended_learning_design.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Riffell, S.; Sibley, D. Using web-based instruction to improve large undergraduate biology courses: An evaluation of a hybrid course format. Comput. Educ. 2005, 44, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonk, C. Best Practices for Online and Blended Learning: Introducing the R2D2 and TEC-VARIETY Models. Available online: https://mushare.marian.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013andcontext=ffdc (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Bernard, R.M.; Borokhovski, E.; Schmid, R.F.; Tamim, R.M.; Abrami, P.C. A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2014, 26, 87–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E. Opening up to open source: Looking at how Moodle was adopted in higher education. Open Learn. J. Open Distance e-Learn. 2013, 28, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhash, S.; Cudney, E.A. Gamified Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippoliti, C.; Baeza, V.D. Using digital badges to organize student learning opportunities. J. Electron. Res. Librariansh. 2017, 29, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Quadir, B.; Chen, N.S. Effects of the badge mechanism on self-efficacy and learning performance in a game-based English learning environment. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2016, 54, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.L.; Montgomery, D. Community college students’ views on learning mathematics in terms of their epistemological beliefs: A Q method study. Educ. Stud. Math. 2009, 72, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlo, S. Mixed method lessons learned from 80 years of Q methodology. J. Mixed Method Res. 2016, 10, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Stenner, P. Doing Q methodology: Theory, method and interpretation. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2005, 2, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.J.; Wehby, J.H.; Feurer, I.D. The social validity assessment of social competence intervention behavior goals. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2010, 30, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R. Q methodology and qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrtek, R.G.; Tafesse, E.; Wigger, U. Q-Methodology and Subjective. J. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 1996, 13, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, B.; Thomas, D. Q Methodology, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 66, pp. 23–25, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Chen, T.-L.; Chen, N.-S. Students’ perspectives of using cooperative learning in a flipped statistics classroom. Aust. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 31, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlo, S. Free speech on US university campuses: Differentiating perspectives using Q methodology. Stud. High. Educ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.B.; Lin, Y.; McCline, R.M. Q Methodology and Q-Perspectives® Online: Innovative Research Methodology and Instructional Technology. TechTrends 2018, 62, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. Political Subjectivity; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1980; Available online: https://qmethodblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/brown-1980-politicalsubjectivity.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Malone, T.W. Toward a theory of intrinsically motivating instruction. Cogn. Sci. 1981, 5, 333–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, S. Afterschool and Digital Badges: Recognizing Learning Where It Happens. In Digital Badges in Education: Trends, Issues and Cases; Muilenburg, L.Y., Berge, Z.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.H.; Schneider, C.; Valacich, J. Enhancing the motivational affordance of information systems: The effects of real-time performance feedback and goal setting in group collaboration environments. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 724–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziopa, F.; Ahern, K. A systematic literature review of the applications of Q-technique and its methodology. Method Eur. J. Res. Method Behav. Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrioni, F. Cross-European Perspective in Social Work Education: A Good Blended Learning Model of Practice. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gillard, L.A.; Lewis, V.N.; Mrtek, R.; Jarosz, C. Q Methodology to Measure Physician Satisfaction with Hospital Pathology Laboratory Services at a Midwest Academic Health Center Hospital. Lab. Med. 2005, 36, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Badges | Name | Criteria and Rules | I/G | F | Q | Issuer | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great team Badge | Complete teamwork: Two people in a group must submit Flash homework; total score of 80 or above. | G | 1 | More than 5 badges in total | Ir | No |

| Completion Badge | Submit work on time; complete the course activities. | I | 3 | 3 badges at most | Ir | No |

| Welcome Badges | Log into the system, register, and provide the required information. | I | Irgr | 1 badge per person | Ir | No |

| Participation Badge | Issued to top 20 in course activities ranking. Rules: 5 points for log-in and 20 for each specified activity completed (including replies and comments in forum, evaluation, peer-assessment, feedback, download course resources, and other learning activities). | I | 2 | 20 badges per time | Ir | No |

| Independent learning badges | Complete independent learning activities on time, including viewing course materials before class; complete pre-class test; and complete after-school test. | I | 1 | 1 badge per person | P | No |

| Communication talent Badge | Issued to students who receive a peer review medal | I | 1 | 1 badge per person | P | S |

| Knowledge talent Badge | Issued to students who achieve more than 80 points in knowledge test. | I | 1 | 1 badge per person | Ir | No |

| Assessment Badge | Complete peer review. | I | 1 | 1 badge per person | Ir | S |

| Grade Badge: Novice | Final examination badges. Novice Grade Badge awarded for less than 70%. Adept Grade Badge awarded for between 71% and 79%. Apprentice Grade Badge awarded for between 80% and 89%. Professor Grade Badge awarded for more than 90%. | I | Once at the end | 1 badge per person | Ir | No |

| Grade Badge: Adept | ||||||

| Grade Badge: Apprentice | ||||||

| Grade Badge: Professor |

| Person No. | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 69 | Male | ||

| 20 | 66 | Male | ||

| 14 | 63 | Female | ||

| 9 | 63 | Female | ||

| 1 | 58 | Female | ||

| 3 | 58 | Male | ||

| 7 | 54 | Male | ||

| 22 | 47 | Male | ||

| 15 | −64 | Female | ||

| 5 | −58 | Male | ||

| 10 | −85 | Male | ||

| 17 | 49 | Female | ||

| 19 | 80 | Male | ||

| 21 | 37 | Male | ||

| 16 | 83 | Male | ||

| 6 | −48 | Female | ||

| 11 | 87 | Female | ||

| 12 | 87 | Female | ||

| 18 | 39 | Male | ||

| 2 | 76 | Male | ||

| 8 | 40 | Female | ||

| 4 | 53 | Female |

| Factor Statements | Factor | Rankings (*) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Factor 1 Neutral learners | ||||

| 33 | Digital badges have a clear objective for learning outcomes; I can learn better. | 4 | −1 | −1 |

| 35 | Digital badges do not represent a person’s true ability. | 3 | −1 | 0 |

| 28 | Digital badges and the websites have insufficient attention. | 3 | −3 | 0 |

| 1 | Digital badges make me actively participate in blended learning. | 1 | 3 | −2 |

| 24 | The network is not convenient, and user experience is not good. | 1 | −3 | 4 |

| 2 | Digital badges are less satisfying than physical rewards | 0 | −4 | −2 |

| 31 | Digital badges add to the fun of interaction and communication. | 0 | 2 | −1 |

| 21 | Badges represent acquired skills and achievements, which encourages me. | 0 | 4 | −4 |

| 10 | Obtaining badges is conducive to communication with classmates | −1 | 3 | 2 |

| 19 | Digital badges improve my learning. | −2 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | Digital badges are novel and unique with a bright design. | −3 | 3 | −1 |

| 25 | Ranking of badges has a negative effect on me. | −4 | −1 | −1 |

| Factor 2 Extreme learners | ||||

| 21 | Badges represent my achievements and stimulate me. | 0 | 4 | −4 |

| 15 | Badges help to foster a sense of competition and improve my shortcomings. | −1 | 4 | −3 |

| 1 | Digital badges make me actively participate in blended learning. | 1 | 3 | −2 |

| 6 | Digital badges are novel and unique with a bright design. | −3 | 3 | −1 |

| 31 | Digital badges add fun to interaction and communication. | 0 | 2 | −1 |

| 36 | Blended learning tends to be compared to traditional education. | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| 27 | Digital badges improve interaction and teaching efficiency. | −2 | 1 | −1 |

| 29 | Digital badges refer to grades. | −3 | 0 | −4 |

| 3 | There is unfair phenomenon of low scoring when students evaluate each other. | 0 | −1 | 0 |

| 20 | The evaluation results of digital badges do not reflect the true level. | 3 | −2 | 3 |

| 30 | Digital badges are not famous or widely used. | 1 | −2 | 0 |

| 14 | Badges are not motivating unless teachers emphasize them in class. | 2 | −2 | 2 |

| 28 | Digital badges and the website have insufficient attention. | 3 | −3 | 0 |

| 24 | The network is not convenient, and user experience is not good. | 1 | −3 | 4 |

| 2 | Digital badges are less satisfying than physical rewards | 0 | −4 | −2 |

| Factor 3 Skeptical learners | ||||

| 24 | The network is not convenient, and user experience is not good. | 1 | −3 | 4 |

| 5 | The display position of a personal badge is not obvious enough | −2 | −1 | 4 |

| 16 | Acquiring a badge rather than acquiring knowledge is not conducive to an intrinsic motivation to learn. | −2 | 0 | 2 |

| 18 | Computer study is troublesome. I don’t like learning on the internet. | −4 | −3 | 1 |

| 22 | Digital badge icons are drab and imperfect. | −1 | −2 | 1 |

| 28 | Digital badges and the website have insufficient attention. | 3 | −3 | 0 |

| 6 | Digital badges are novel and unique with a bright design. | −3 | 3 | −1 |

| 31 | Digital badges add fun to interaction and communication. | 0 | 2 | −1 |

| 1 | Digital badges make me actively participate in blended learning. | 1 | 3 | −2 |

| 2 | Digital badges are less satisfying than physical rewards. | 0 | −4 | −2 |

| 13 | Digital badges give timely feedback on learning. | 2 | 0 | −2 |

| 17 | Online learning is convenient and conducive to independent learning. | 1 | 1 | −3 |

| 21 | Badges represent acquired skills and achievements, which encourages me. | 0 | 4 | −4 |

| Factor Statements | Factor | Rankings (*) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 4 | Peer assessment increases the chances of learning from each other. | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | The ranking rules of digital badges in blended learning activities are reasonable and clear. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | Digital badges, like Red Flowers for primary school students, are not suitable for college students. | −3 | −4 | −3 |

| 12 | Digital badges are easy to use, but they reduce learning supplies. | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 34 | I am not interested in the interactive activities of obtaining digital badges and have little enthusiasm for them. | −3 | −3 | −3 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Fan, Q.; Ji, Y. Students’ Perception of Using Digital Badges in Blended Learning Classrooms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072151

Zhou L, Chen L, Fan Q, Ji Y. Students’ Perception of Using Digital Badges in Blended Learning Classrooms. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072151

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Li, Liwen Chen, Qinman Fan, and Yueli Ji. 2019. "Students’ Perception of Using Digital Badges in Blended Learning Classrooms" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072151