Abstract

For the rural districts of China to get an economically and socially sustainable development, the strengthening of agricultural cooperatives is essential. This study aims at presenting a model about how social capital within the cooperatives can be converted into financial capital to the benefit of both the cooperative and the members. Case studies of four cooperatives serve as illustrations. There is a large amount of social capital in these cooperatives, with their operations simple enough to allow members to be involved. The supplying members (common members) are few and well acquainted with one another. They have close relationships with those individuals (core members) who have the dominating ownership and who run the cooperatives. These case cooperatives were chosen because they have innovative financial solutions. For example, members let their private assets and those of the cooperative constitute joint collateral when money is borrowed from financial institutions. In another case, the members trust each other sufficiently for there to be a mutual fund that lends money both to members and their cooperative. Yet another model involves members having low demands concerning capital returns when lending to their cooperative.

1. Introduction

It has been claimed that cooperatives in Western economies often encounter difficulties in obtaining financial capital [1,2], yet this is also the case in China [3]. One explanation for these difficulties is that the cooperatives’ collective ownership and governance do not suit selfish members. Cooperative property rights mean that selfish members have an incentive to be free riders, wanting others to invest. Individualistic members want returns on their investments, whereas a cooperative’s task is to promote the interests of the membership as a whole [4,5]. Self-interest-seeking behaviour is difficult to combine with the view that a cooperative’s financial capital is a tool for achieving social objectives.

Financial capital constraints can also be explained in terms of cooperative principles, as stated by the International Cooperative Alliance. For example, the principle of “voluntary and open membership” means that the stock of equity capital is unstable and risky, which is not appreciated by investors. The principle of “democratic member control” implies that members who contribute a large amount of share capital do not have any more control than those who contribute less. The principle of “member economic participation” indicates that members’ financial contributions receive limited compensation, if any at all. The principle of “autonomy and independence” implies that external financial capital would inhibit member control.

These observations may explain why a large number of agricultural cooperatives in Western economies have abandoned the traditional cooperative form in recent decades [6]. Increasing competition has induced many cooperatives to embark on a vertical integration strategy in attempts to reach the more lucrative markets for value-added products. As this strategy requires large investments, many cooperatives have acquired financial capital from outside sources [1,7]. At the same time, there is a process of horizontal integration in the form of mergers. However, large and heterogeneous memberships mean that the level of members’ social capital has diminished and thereby their incentives to invest. When farmers do not feel particularly involved, the cooperatives’ strategies of capital-demanding expansion are not in harmony with the prerequisites for traditional cooperation [8,9]. However, a more general conception of cooperatives says, “In a cooperative, the user is the focal point, with the direct status of user, owner, and control vested in the same individual” [10], p. 85. Since this definition does not require that the members have neither full ownership nor full control of cooperatives, the new organisational structures could be categorised cooperatives, though not traditional cooperatives.

When studying cooperatives’ financial constraints, researchers have used a variety of theories such as agency theory, property rights theory, transaction cost theory and governance theory [11,12,13,14]. These studies shed light on the many issues that cooperatives face in the acquisition of financial capital, but because they are based on a presumption of members seeking individual benefits, they do not problematise the farmers’ social motivations, something that would have been possible from a social capital theoretical perspective. The present study applied social capital theory to explore the financial issues faced by cooperatives. This paper aims to explain how social capital within Chinese cooperatives can stimulate the acquisition of financial capital, including both equity capital and borrowed capital, as well as capital to both the cooperative’s business activities and members’ operations. This is illustrated using four case studies of agricultural cooperatives in Fujian Province, China. The rationale for the study is that the strengthening of cooperatives is essential for the development of economic sustainability in the rural districts of China. A number of studies have investigated social capital in an agricultural cooperative context. They indicate that social capital is essential or even serves as the basis for cooperative businesses [8,15,16,17]. If members are to be willing to patronise, govern and finance the cooperative, there must be trust between the members and between members and the leadership [17].

Studies of Chinese agricultural cooperatives similarly indicate the importance of social capital [18,19,20]. For example, Liang, Huang, Lu and Wang [20] found a positive relationship between the amount of social capital and members’ participation in technical training and general meetings. These factors were positively related to the cooperatives’ economic performance. Yu and Nilsson [3] studied the importance of social capital for the financing of Chinese cooperatives and their members. Based on a survey of a sample of 60 cooperatives, the authors found that social capital helps cooperatives obtain bank credits. Social capital also makes members more likely to obtain financial services, such as guarantees for member loans, and cooperatively convinced members are more willing to provide financial capital. Thus, the existence of social capital is beneficial for obtaining equity and borrowed capital, capital for cooperatives and members, and capital from members and external sources.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides a theoretical framework of social capital in relation to the financial capital of cooperatives, while Section 3 reports on the structure of agricultural cooperatives in China. Section 4 presents how the empirical investigation was conducted, and the results are reported in Section 5. In Section 6, the investigated cooperatives’ financial capital acquisition is discussed in relation to their social capital. Finally, conclusions are drawn in Section 7.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Social Capital in Cooperatives

Social capital, according to Bourdieu [21], is a real or potential set of resources, which exists in networks that people have established in familiar and cognitive relationships. Grootaert and Bastelaer [22], p. 19 distinguish between structural social capital (objective and externally observable) and cognitive social capital (subjective and intangible), suggesting that “structural social capital facilitates information sharing, and collective action and decision making through established roles, social networks and other social structures supplemented by rules, procedures and precedents. And cognitive social capital refers to shared norms, values, trust, attitudes, and beliefs.”

Putnam [23] argues that social capital facilitates coordination and communication, incentivises partnership and reduces opportunism. Thus, it also reduces both transaction costs and agency costs [24,25]. Narayan and Pritchett [26] present a number of effects that may accrue from social capital: it facilitates collaboration; it improves governments; it leads to more community action, thereby solving local common property problems; it strengthens links between individuals, thereby speeding up the diffusion of innovations; it improves the quantity and quality of information flows; and it pools risks and allows people to pursue risky activities with high returns.

Social capital exists in all organisations—cooperatives, investor-owned firms and others—just as they all need financial capital. When there is social capital within organisations, it is a matter of bonding social capital [27]. Employees must communicate to coordinate their work tasks and the leadership of the organisation must be accepted by its employees. Likewise, bridging social capital is necessary irrespective of the organisational form. The firm must enjoy trust within its business environment, and the firm’s products must be appreciated by its customers. Together, social, financial, human and physical capital provides humans with economic, social and information services [28].

Cooperatives are networks that are established to provide specific services. The network character implies that cooperatives are social capital-based organisations [8]. Cooperative members must have sufficient trust in one another and in the elected representatives not to fear that others will be deceitful. Coordination within cooperatives and the allocation of resources depend on mutual understanding in the relationships between members. In short, social capital is a fundamental asset of cooperatives: “It can be proposed therefore that the economic principle of cooperative organisation is social capital shared by its membership; social capital performs the same organisational role for cooperatives as price and authority relation – respectively for markets and hierarchies. Consequently, cooperatives can be regarded as representing the social capital-based organisation”. [29], p. 7.

Social capital within a cooperative society is positively related to member satisfaction, which in turn is related to the size and degree of homogeneity within the membership and the size and complexity of the cooperative business. That is to say, that geographical proximity tends to increase the amount of trust and collaboration. Likewise, if the cooperative’s business operations are simple, its members will feel more involved than they would if the cooperative had complex operations [9].

2.2. Conversions between Forms of Capital

If organisations are to perform various production activities, they need both financial and social capital, but the activities can be performed with different combinations of financial and social capital. This is to say that an organisation that is based on one form of capital has to convert this into another form of capital in order to get an appropriate mix of the two forms of capital [28]. Similarly, human capital can be acquired through recruiting and incentivising individuals, and physical capital can be acquired in exchange for financial capital. Several researchers mention conversions of social capital. According to Valentinov, social capital is “made up of social obligations (‘connections’), which is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital” [30], p. 116. Burt [31] explains that individuals acquire opportunities to use other forms of capital through their friends, colleagues and other contacts.

All financial capital in cooperatives can be regarded as having been converted from social capital [8]. It is only because members trust one another that they dare invest in shares and pay membership fees as well as contribute with various efforts. The cooperatives have built up unallocated funds because members have voluntarily abstained from some part of the patronage refunds and dividends that they could otherwise have received. The borrowed capital of cooperatives is the result of social capital, because the membership, through the board of directors, has succeeded in building up trust among lenders or has provided securities to them. This process of building up financial capital has gone on throughout a cooperative’s existence, which is to say that members have sympathies even for future generations of members. Cooperatives with considerable social capital have advantages in obtaining financial capital. Thus, when a cooperative faces a financial capital dilemma, its members are often willing to find a joint solution. Individuals may realise that their own goals are related to the group’s goals. A reduction of opportunism is achieved through the internalisation of group goals [8].

Correspondingly, investor-owned firms convert their financial capital into the social capital they need. They use financial resources to incentivise their labour force and build up goodwill in relation to the business environment. They pay for enjoying loyalty from customers and other business partners, the labour market, political interest parties etc. Likewise, when an investor-owned firm has financial difficulties, its owners are often willing to rescue the money they have already invested by injecting more money.

Conversions from one form of capital into another are, however, associated with costs for the actors who conduct the conversion. The conversion costs correspond to transaction costs that arise when financial capital is turned into physical capital. In order to avoid unnecessary conversion costs, actors who are based on a specific form of capital prefer a production technology where this form of capital can be used. Thus, cooperatives will prefer to use social capital for their activities and less financial capital, while the opposite is the case for investor-owned firms. Production cooperatives often rely on labour-intensive production rather than capital-intensive production because they have a large amount of social capital and a shortage of financial capital [32]. Members are willing to invest their own labour in the cooperative and may enjoy working together. Members of cooperatives have historically been willing to work voluntarily with little or no payment.

When deciding on capital conversions, actors have to think in terms of marginal effects. Actors who possess an abundance of capital of one form will attach a low value to the last used unit of this capital. Therefore, these actors may economise less with this form of capital and are prone to use it for their activities. The marginal value of this form of capital is low. Correspondingly, when an actor has a strong need for another form of capital, this will be judged to have a high marginal value. Therefore, conversion costs vary, depending on how valuable actors consider their present stock of a certain form of capital to be and how greatly they need another form of capital.

While financial capital can be measured in monetary terms, there is no general measurement for social capital. Only various proxy variables can be used [3,19]. Thus, estimations of the need and the stock of social capital are associated with great uncertainty. For example, it is difficult to know beforehand whether only limited information is necessary to incentivise members to raise money in their cooperative, or if the amount of social capital is so small that members do not want to invest.

It could be argued that actors who have a large amount of a certain form of capital will have a chance to acquire even more of this form of capital. These actors can make better use of this capital than those with less capital. if a cooperative enjoys considerable social capital among its membership and in its environment, this cooperative will be so successful that it becomes even more appreciated by its interest parties [33]. The members will remain as patrons, be willing to invest more money, and take part in the governance processes. The opposite development will take place in a poorly performing cooperative [17]. Similarly, a poorly performing investor-owned company will not be treated favourably by investors. In both cases, the downfall may take place quickly, although probably even more so in cooperatives because of the difficulties in discerning how social capital is declining. If a trusted actor actually turns out to be deceitful, the trust may disappear abruptly. However, building up social capital is a long-term and difficult endeavour.

Thus, when an actor converts social capital into financial capital, it does not necessarily mean that this actor will end up with a smaller stock of social capital. If the conversion is deemed successful, the amount of social capital may in contrast increase. The members of a cooperative may raise financial capital, which the cooperative invests in such a way that social capital within the membership will grow. Similarly, an investor-owned firm may use its financial capital to incentivise staff, with the result that the firm’s financial capital increases.

3. Chinese Agricultural Cooperatives

Cooperative structures have a long history in China. “[M]any years before the birth of Christ, the Chinese developed sophisticated savings and loan associations not too different from those we have today” [34], p. 106. More Western-style cooperatives evolved in the early 1900s [35]. During the 20th century, various forms of cooperative and collective organisation forms existed. The present-day cooperatives are, however, a result of the Law on Cooperatives (Law of the People’s Republic of China on Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives) was passed in 2007. The number of farmer cooperatives was in that year 26,400, while official statistics report 2173 million cooperatives by the end of 2018. The number of registered cooperatives has shown an average annual growth of 65% since 2007. By the end of October 2017, more than 100 million households had joined the cooperatives, accounting for 46.8% of the total number of households in China, with an average membership of about 60 households.

Chinese cooperatives are quite different from cooperatives in most of the rest of the world [36]. The law does not comply with the cooperative principles that are recognised in most countries [37,38]. The Chinese government possibly realised that the international principles would hamper investments in cooperatives in a country with many impoverished and poorly educated farmers. Hence, the law includes a clause that says that members may be both producers of agricultural products and service providers, and the latter group may include providers of financial capital and farm inputs.

Thus, some individuals and firms may become members—core members—by investing in the cooperatives, while others—common members—invest small amounts, if any at all [32]. Other than being the main owners, core members have most of the governance power, also because they are better educated, are often entrepreneurial, and have political contacts. The large group of common members are primarily suppliers of agricultural products to the cooperatives’ processing and marketing activities. They generally have restricted financial resources, limited business knowledge and a poor sense of cooperation. Because Chinese cooperatives have dual memberships, it may be questioned whether they are cooperatives. However, according to the general definition of cooperatives they could be considered cooperatives [10].

Core members’ capital contributions have played a major role in the years since the cooperatives were established. A large number of investor-controlled cooperatives have been formed. However, the core members also satisfy the common members’ interests because the common members get an assured marketing channel for their products as well as services, advice and an opportunity to borrow money. Common members have to compromise with core members. They sacrifice part of their control rights and residual claim rights for the benefits that cooperatives offer. Core members and common members are mutually dependent upon one other. However, doubts have been expressed concerning the core members’ control, which may weaken the cooperative character. Common members’ interests are not the main objective of the cooperatives. A focus on core members’ financial interests combined with downplaying democratic control may lead to the cooperatives resembling investor-owned firms [32,34,39]. An emphasis on financial capital and neglect of social capital affects the nature of cooperatives.

The financing potential of common members is limited and they tend to regard financing issues as a matter for the core members. Many common members want to invest only the compulsory basic membership fees. Reliance on the strength of core members and the ignorance of many common members may extend the cooperatives’ financial constraints [39].

The fact that the Chinese cooperatives have two categories of members implies heterogeneity within the memberships. When researchers write about membership heterogeneity, there are different interpretations. On the one hand, such heterogeneity may imply problems such as costs of decision-making, postponement of urgent decisions, or favourable treatment of a specific group of members [40]. On the other hand, membership heterogeneity may be positive, if two or more member categories have supplementary attributes and if the member categories have sufficiently strong social relations to acknowledge that they are interdependent [41]. It is likely that the common members and the core members of Chinese cooperatives supplement each other in this way.

Chinese cooperatives are typically small and local. The members’ production is often labour-intensive and takes place on small plots of land. For example, according to the statistics of the Department of Agriculture, in 2017 the total number of households in Fujian Province was 7988 million, and the households’ area of contractual operation was 121,000 hectares. Thus, the average household operating area was 0.015 hectares or 150 m2. The cooperative members come from the same village and have a consistent culture and common values. This reduces the cost of coordination, which provides good conditions for social capital. Chinese cooperatives also show embeddedness, implying that they depend on rural areas, social conditions and local markets.

A specific feature of Chinese cooperatives is that provincial governments and sometimes the central government give “honours” to cooperatives that are meant to be role models for other cooperatives [3,19]. An honour means not only large financial governmental support but also that a cooperative is deemed solid and reliable, and so, this firm enjoys social capital in the surrounding society. Official statistics show that 8.5% of the cooperatives were granted honors by the Department of Agriculture in 2017.

4. Approach

To illustrate how Chinese agricultural cooperatives handle their financial issues with the help of social capital, four case studies are presented. These were identified during interviews conducted by the research team in May and July 2016 and July 2018 with a group of 66 cooperatives that were randomly selected from an official list of cooperatives in Fujian Province. During these interviews, four cooperatives stood out to have especially novel financial models. Therefore, they were chosen because they show how social capital within memberships stimulates innovative solutions for cooperative financing and not because they are representative of the province’s cooperatives [42].

Fujian Province is in southeast China. The investigated cooperatives are located in Xiamen region and Gutian Ningde region. Xiamen is the province’s most developed region. Its cooperatives were established earlier and they are stronger than those in other parts of Fujian Province are. The cooperatives in Gutian Ningde were formed a few years later and are not very strong.

Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected from secondary sources, and personal interviews were conducted in two cooperatives in Xiamen and another two in Gutian Ningde. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with common members as well as with the cooperatives’ chairpersons and managers. The interviews were based on a semi-structured questionnaire. Most of interviewees were male and they were aged between 36 and 62 years.

The cooperatives in the two regions are presented separately because they operate under different conditions. Gutian Ningde is a pilot region of rural financial innovation. Since 2016, the government has carried out some reform projects that overturn previous rules that did not allow farmers to use their rights to contracted land or their property as collateral to obtain loans. The region, which has a traditional industry of tremella fungi production, has benefited from the pilot reforms. Xiamen is not covered by these rules. Cooperatives in the two regions therefore apply different financial strategies. The Xiamen cooperatives follow internal financial strategies, i.e., capital from members, while the Ningde Gutian cooperatives have an external financing practice, mainly in the form of loans from financial institutions.

All four cooperatives investigated have received an honour from the provincial government. They therefore enjoy high respect not only in governmental circles but also in the rural communities in which they operate. Their leaderships can be expected to have good relationships with financial institutions. All these factors indicate that they enjoy bridging social capital within the communities, and thus have a greater chance of acquiring financial capital. Another factor contributing to the cooperative’s strong positions in the local communities is that all of them sell their products under their own brands.

5. Results

5.1. Xiamen

Table 1 presents general data on the two investigated cooperatives in the Xiamen region. The members of both are mainly local villagers, and both were established shortly after the law on cooperatives was introduced. Xiamen Sanxiushan Vegetable Professional Cooperative (Sanxiushan Cooperative for short) was actually the first cooperative in the region. The other cooperative is Qinlu Flower Farmers’ Cooperative (Qinlu Cooperative for short).

Table 1.

Characteristics of two cooperatives in the Xiamen region.

5.1.1. Social Capital

Given the limitations of having two categories of membership, the cooperatives’ governance structure resembles member democracy. The Sanxiushan Cooperative holds a general meeting for all members once a year and the board of directors meets 12 times a year. A supervisory board with member representatives meets at least four times annually. Two to three training sessions for members are arranged every year. Nearly two thirds of the members have participated in the festival activities held by the cooperative every year. The core members of the cooperative and larger common members communicate with each other about once a week. The chairperson of the cooperative was very enthusiastic about it:

“I know all the members of the cooperative, and am familiar with about half of them… I’ve been engaged in agriculture since 1991, and rented the land of nearby farmers to grow vegetables, fruit and maize. I joined the cooperative with all my land when it was established. Because of good collaboration, farmers in the vicinity are also very confident about handing over land for me to manage. In fact, since joining the cooperative, my personal income has not yet increased, but considering the future and the development of the members, I’m willing to put my land into unified management. The monthly salary from the cooperative at the moment is only 3000 yuan, which is rather low for a manager, but it takes almost all my energy.” (Interview with the Chairperson of Sanxiushan Cooperative, July 2016)

To explore the extent of social capital among common members, the research team conducted interviews with a randomly selected sample of common members within the Sanxiushan Cooperative. Interviews were conducted with 25 of the cooperative’s 141 common members in July 2018. The age of the interviewees was between 36 and 62 years. All but one was male. Most respondents had had high school education. The results indicated a significant amount of social capital among the common members. Thus, 96% agreed that they are familiar with the cooperative’s leadership, and all the respondents trusted the leadership; 80% actively participated in the cooperative’s meetings; 92% regarded themselves as loyal members; 92% preferred to sell their products to the cooperative. Furthermore, 96% were satisfied with their cooperative’s services, and the same percentage believed that the cooperative works to satisfy member interests and were willing to assist the cooperative financially.

5.1.2. Financial Capital

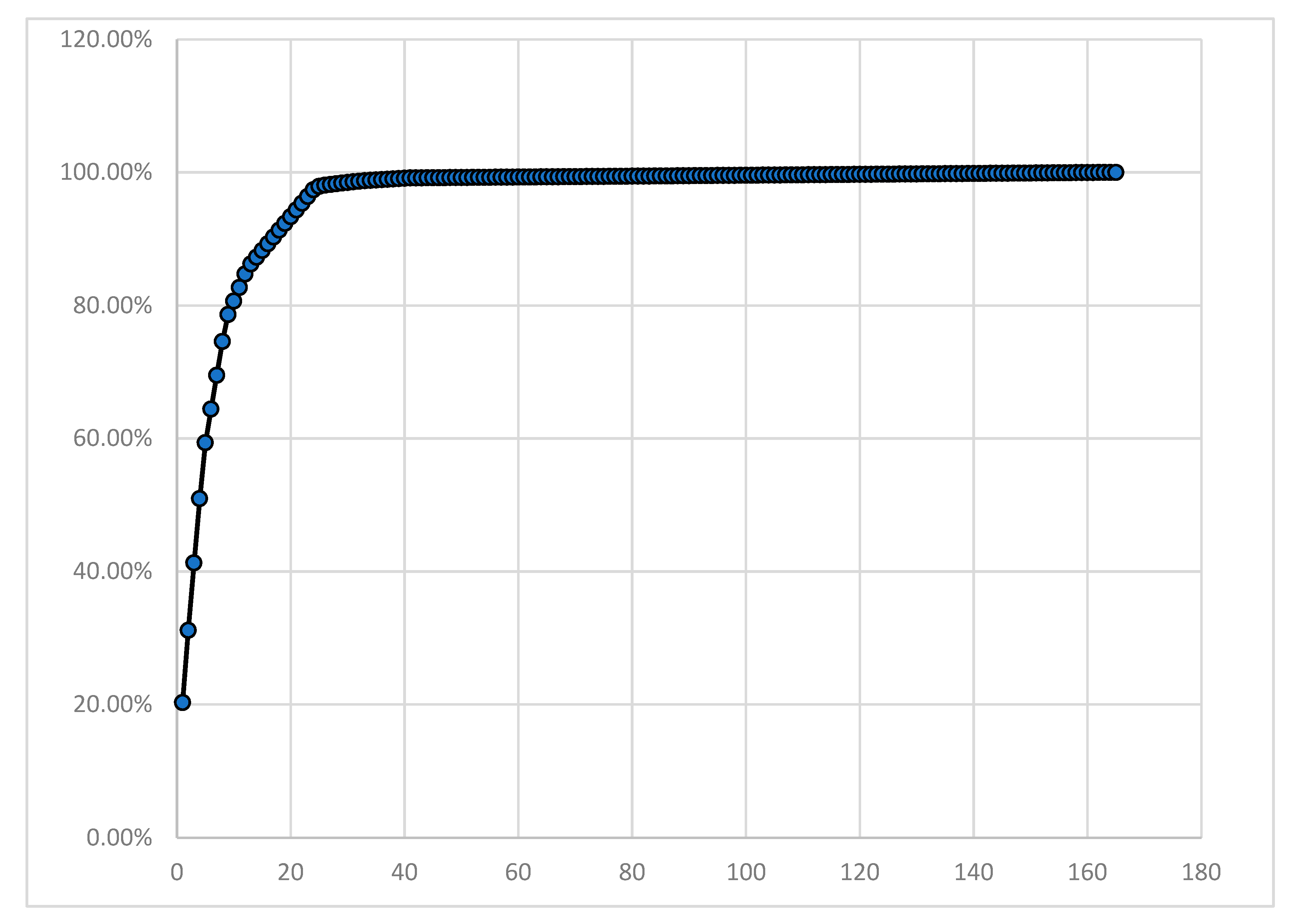

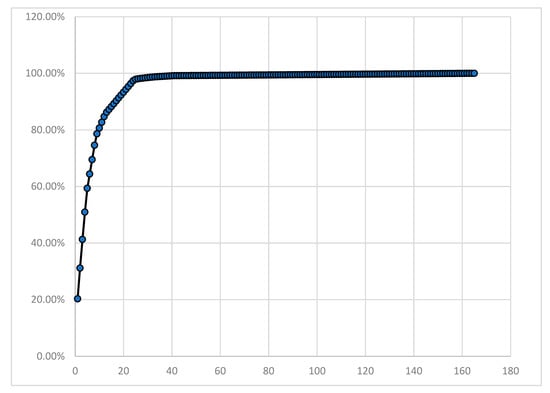

As in most other Chinese cooperatives, the ownership of shares was skewed in the cooperatives investigated. Thus, in the Sanxiushan Cooperative, core members who have invested more than 10,000 yuan hold about 97% of the equity capital, but represent just 14.5% of the membership (Figure 1). The largest shareholder, with about 20% of the equity capital, is a vegetable growers’ association, which is a non-profit non-governmental organisation. However, it does not participate in the cooperative decision-making but is only aiming for capital dividends. The second largest share (11%) is owned jointly by a group of five individuals. One of these is the general director, while the other four are only investors. The third largest share (10%) is financed by the chairperson. Therefore, the chairperson is the most important core member. Furthermore, each of the 123 common members has invested 100 yuan of equity capital. The total share capital of the Sanxiushan Cooperative has risen from 1030 million yuan in 2007 to 1478 million yuan in 2010.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Equity Capital in Sanxiushan Cooperative.

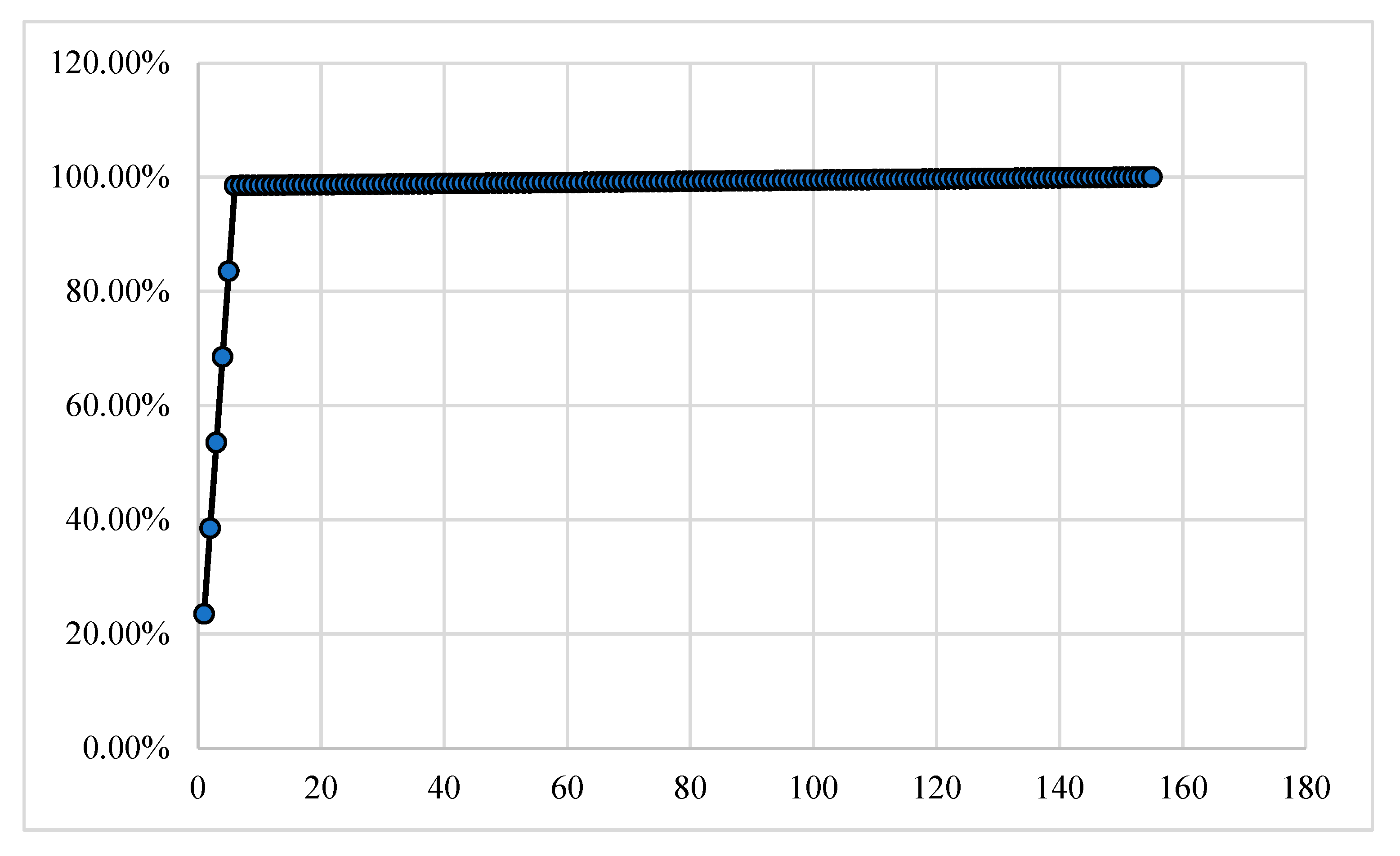

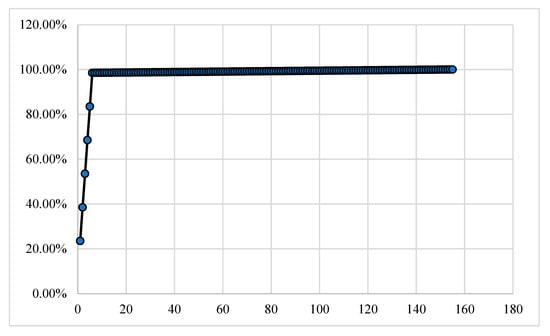

The Qinlu Cooperative has six core members and 149 common members. The largest shareholder is the chairperson, who holds 23.5% of the equity capital. Core members, who account for nearly four percent of the membership, together contributed over 150 million yuan, corresponding to 98.50% of the equity capital (Figure 2). Most of the common members contributed 1000 yuan. The skewed nature of the ownership and control may indicate that these cooperatives are characterised by diverging interests. Nevertheless, the member categories support one other, not only because they are interdependent but also because they have social relations.

Figure 2.

Distribution of equity capital in the Qinlu cooperative.

At its establishment, the Sanxiushan Cooperative raised most of its capital from both core and common members through an auctioning procedure. Members were asked to say at which interest rate they would be willing to lend money to the cooperative, and the ones who indicated the lowest interest rate were chosen as capital providers. The common members of the Sanxiushan Cooperative lent a considerable amount of capital to the cooperative in 2014–2016. The cooperative could have got bank loans instead, but the application procedure is complicated and requires a great deal of time for examination and approval. Furthermore, loans from agricultural funds are often temporary and the amounts are uncertain. Therefore, members see the advantages of giving credits to the Sanxiushan Cooperative.

In 2014, the Sanxiushan Cooperative needed liquidity capital of one million yuan over the following three years. All the members were asked to provide a three-year loan of 400,000 yuan, a two-year loan of 200,000 yuan and a one-year loan of 400,000 yuan. To obtain a low interest rate, an auctioning process was used again. The loans from the members amounted to between 1000 and 50,000 yuan. One interesting observation concerns the distribution of loans from core members and common members (Table 2). The three-year loans came mainly from core members, while common members were more willing to lend money for one or two years. Core members were thus more involved in financing and more willing to take risks. However, the common members were willing to lend money even though their financial status is poor. The total amount of loans from common members was 963,000 yuan from 2014 to 2016, which accounts for nearly 60% of all member loans and is more than the loans from core members.

Table 2.

Financing of the Sanxiushan Cooperative in 2014.

In 2015, however, the members found that the auctioning procedure had led to such a low interest rate that it was unfair. Thus, the members agreed upon a fixed capital remuneration of one percent per month. Members who were willing to lend money registered with the cooperative, and then the cooperative decided on financing options. In this way, the cooperative obtained loans from the members amounting to 400,000 yuan in 2015 and 200,000 yuan in 2016.

The Sanxiushan Cooperative has 165 members: 24 core members and 141 common members. In 2014, 99 members (60%) took part in this financing activity: 21 core members (88% of the core members) and 78 common members (55% of the common members) (Table 3). The cooperative’s chairperson expressed his satisfaction with the member’s financial contributions:

Table 3.

Financial participation by core members and common members.

“Financing members can obtain the required funds in a timely manner. The efficiency of the use of funds is very high and most members have trust in cooperatives so are willing to lend idle money to cooperatives if the cooperatives need money. I can use my personal property as a guarantee.” (Interview with the Chairperson of Sanxiushan Cooperative, December 2016)

The Qinlu Cooperative mainly uses mutual credit for the financial needs of both the cooperative and its members. In 2008, 18 members established an internal mutual fund within the cooperative. The amount of the mutual fund was 86,400 yuan, financed by these members, but by 2012 the number of participants had risen to 65 and the amount of the mutual fund was 960,000 yuan. The members apply for loans from this credit fund, with the loans guaranteed by other members. Since it started, the members’ internal mutual fund has operated in accordance with its statutes without any amounts being overdue, and the members’ financial problems have been eased. The members have been able to expand their production facilities.

5.2. Gutian Ningde

Some characteristics of the two investigated cooperatives in the region of Gutian Ningde are shown in Table 4. Gutian Nongfen Edible Fungus Cooperative (abbreviated as Nongfeng) was established in 2013. Its largest (core) member holds 20% of the shares, and the ten largest members hold 40%. Gutian Fumin Edible Fungus Cooperative (Fumin for short) was established in 2011. Its largest shareholder holds 10% of the shares, and the five largest shareholders hold nearly half. In both cooperatives, the core members are in control and receive much of the surplus. However, most core members are also major producers of fungi, so the identity of the suppliers and capital owners is the same.

Table 4.

Characteristics of two cooperatives in Gutian Ningde region.

The main financial problem in both the Ningde Gutian cooperatives is that their members cannot obtain enough money for profitable investments in their agricultural operations. One solution is that the cooperatives lend money to members on the basis of private contracts with them. Thus, the members of the Nongfen Cooperative have lent 100 million yuan to the cooperative and the Fumin Cooperative members have lent 70 million yuan. The cooperatives accept the members’ land management rights, farmhouses, mushroom sheds and other production facilities as collaterals. No financial institution would accept these assets as collaterals. While the members thus obtain loans from the cooperatives, the cooperatives are able to borrow corresponding amounts from financial institutions. In so doing, the cooperatives use part of their equity as a risk guarantee to these financial institutions. Through this arrangement, members may borrow amounts six times greater than the amounts deposited by the cooperatives in the financial institutions.

In 2015, the two cooperatives joined a farmers’ cooperative union that offers rural social services, including credits, on a non-profit basis. When the interviews were conducted in 2016, the members of the two cooperatives had received about 170 million yuan in loans. Thanks to the arrangement with the cooperative union, the farmers have lowered their credit costs. The annual interest rate is 5.93%, which is clearly lower than the ordinary interest rate. A member can take out loans of between 50,000 and 300,000 yuan at a time. According to an interview with the chairperson of one Nongfen cooperative in 2018, the number of farmers who have received financing assistance has increased by approximate 15 percent every year since 2016, and some farmers have alleviated their poverty as a result.

6. Discussion

6.1. Financing Model and Operational Structure

Since the investigated Xiamen cooperatives are not involved in much processing of products, the need for funding is small and temporary. To obtain small funds quickly for short periods, financing from members is convenient. This presupposes the trust of members, which reduces the moral hazard in transactions and opportunistic behaviour [43]. The cooperatives write informal agreements with their members, based on social capital [44]. Therefore, both cooperatives indicated that it is easy for members to raise funds.

Because the Ningde Gutian cooperatives involve themselves in processing the members’ products, they need considerable and long-term capital for investments in fixed assets such as equipment and buildings. Internal financing from members fails to meet such financing needs. Therefore, external financing is needed.

6.2. Internal Financing and Social Capital

The Xiamen cooperatives acquire money from both its core and common members. The relationships within the memberships as well as between the members and the leadership are expressions of structural social capital. These relations give rise to trust and an awareness of financial participation, which express cognitive social capital [3]. There is frequent interaction between the cooperatives and the members. The chairperson’s dedication strengthens the ties between members and the leadership. This social capital has made financial initiatives from the cooperative possible. The fact that members have repeatedly injected money into the cooperatives indicates that the amount of social capital has increased due to members’ satisfaction with the cooperatives’ investments (Table 3). The members have considered the costs of converting social capital into financial capital to be outweighed by the benefits of having cooperatives with a stronger financial status.

When people involve themselves in joint action, there is a risk that some of the participants may be deceitful. However, the members who take part in the mutual credit funds seem not to fear such a risk. Both the number of participating members and the amounts of deposits are increasing. Such an initiative presupposes both horizontal and vertical trust. There is bonding social capital within the group of common members, implying that the members trust that they will not be cheated or let down by the others [16]. Likewise, the vertical relationship between common members and the group of core members is a kind of bridging social capital [16]. Those who have involved themselves in the mutual fund have trust in the cooperative’s leaders who administer the fund. One interpretation is that social capital generates an even larger amount of social capital.

When common members get more involved in the cooperatives, the costs of converting social capital into financial capital will be reduced. Strong involvement is likely to strengthen the common members’ position in the governance of the cooperatives. As the common members acquire greater ownership, it may be that core members will be willing to give more power to the common members.

6.3. External Financing and Social Capital

The Gutian Ningde cooperatives guarantee their members’ loans from financial institutions and, in return, the cooperatives get collaterals from their members, consisting of land leasing contracts and various production means. These assets would not be accepted as collaterals if the members wanted to borrow from financial institutions. This arrangement implies that members become vulnerable due to the risk that some members are deceptive, and so the members must have a significant amount of trust in one another and in the cooperatives’ leadership. There is a need for information exchange, which reduces information asymmetry. The members benefit from this arrangement in the form of good financial terms.

The cooperatives and the credit union form a network composed of their respective members. As the cooperatives are well respected by their members and because everyone in the region knows one another, the cooperatives have a good understanding of their members [3]. This facilitates the flow of information from members and reduces the cost of supervision. The cooperatives’ risk deposits and a good relation to government provide the basis for the guarantee.

The written but informal agreements between the members and the cooperatives would not be possible without trust. Since not all the possible conditions can be stated in these agreements, there must be trust to overcome potential side effects and thus reduce the cost of contract execution [44].

For the two Ningde Gutian cooperatives, a balance between social capital and the core members’ financial capital is essential. Social capital has been built up during a long-term collaboration between one of the chairpersons and the local credit cooperatives. This contributes to the financial institutions accepting the cooperative as a guarantor and providing loans to farmers. Another contributing factor is that the cooperatives deposit large amounts of risk capital, which originates partly from the cooperatives’ equity capital and partly from local government.

The Ningde Gutian cooperatives’ financial practice indicates that social capital promotes credit financing. Informal contracts between the cooperative and its members are possible due to social capital [43]. The formal contract between the financial institution and the cooperative presupposes that members’ assets function as collaterals. Likewise, the core members’ financial contribution is partially compensated by income rights. Thus, the different member categories get their interests satisfied at the same time.

7. Conclusions

This paper explains how social capital within memberships can alleviate financial problems in agricultural cooperatives. Well-functioning cooperatives are instrumental to raise the living conditions of the rural population. They contribute to economic and social sustainability in the rural areas. The theoretical reasoning is based on the presumption that humans are social creatures who interact with each other in order to obtain common goals i.e., a social capital approach is used. The empirical analyses consist of four case studies of Chinese cooperatives that need both equity capital and borrowed capital for the cooperatives’ business activities and their members’ farming operations. Chinese cooperatives have good conditions for considerable social capital because many of them have a small number of members who are local and know one another. The cooperatives’ operations are simple enough to enable members to be involved. The case studies show that social capital exists despite the Chinese cooperatives having two categories of members. The common members are mainly suppliers of agricultural products, while the smaller group of core members dominates with regard to ownership and governance. However, because the two groups are interdependent, there is sufficient trust to enable financial capital to be raised for the benefit of both the cooperatives’ businesses and the members’ agricultural production.

One solution is that the cooperative’s assets and members’ assets together serve as collateral when money is borrowed from financial institutions. Another is the establishment by members of a mutual fund that lends money to both members and the cooperative. Yet another model is that members have low requirements concerning capital returns when lending money to the cooperative.

A theoretical interpretation of these models is derived from the view that cooperatives are based on social capital. In the infancy of cooperatives and throughout their existence, the trust of members lies at the origin of their financial capital. The members have been willing to invest and to abstain from parts of the cooperatives’ profits, and this money has been added to the cooperatives’ funds. As cooperatives mature, they will gradually have an increasing need for financial capital. When social capital is converted into financial capital, this does not mean that social capital within the membership diminishes. In fact, evidence shows the opposite: if the cooperative is successful with its investments, the amount of social capital within the membership will increase, and then members will want to provide even more financial capital.

There is a risk that the leaderships of many Chinese cooperatives do not exploit the potentials of social capital within their memberships because they are often investor-controlled, i.e., a small number of core members are the prime owners and eager to keep control of the cooperatives. Without a balance between social and financial capital, the dominance of investing core members may result in weak cooperatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y. and J.N.; Data curation, L.Y.; Formal analysis, J.N.; Investigation, L.Y.; Methodology, L.Y.; Writing—original draft, L.Y. and J.N.; Writing—review & editing, L.Y. and J.N.

Funding

China Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (Grant no. xjq201632) and Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University Research Fund for Young Teachers (Grant no. 2013xjj27) provided funding for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflict of interest.

References

- Chaddad, F.R.; Cook, M.L.; Heckelei, T. Testing for the Presence of Financial Constraints in U. S. Agricultural Cooperatives:An Investment Behaviour Approach. J. Agric. Econ. 2005, 56, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijman, J.; Iliopoulos, C.; Poppe, K.J.; Gijselinckx, C.; Hagedorn, K.; Hanisch, M.; Hendrikse, G.W.J.; Kühl, R.; Ollila, P.; Pyykkönen, P.; et al. Support for Farmers’ Cooperatives Final Report; WUR: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Nilsson, J. Social capital and the financing performance of farmer cooperatives in Fujian Province, China. Agribusiness 2018, 34, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, A.M. The changing values of the cooperative and its business focus. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1997, 79, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, M.; Giannakas, K. Agency and leadership in cooperatives: Endogenizing organizational commitment. In Vertical Markets and Cooperative Hierarchies; Karantininis, K., Nilsson, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J. Governance costs and the problems of large traditional cooperatives. Outlook Agric. 2018, 47, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, M.; Hueth, B. Cooperative conversions, failures and restructurings. An overview. J. Coop. 2009, 23, i–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov, V. Social capital and organisational performance: A theoretical perspective. J. Inst. Innov. Dev. Transit. 2004, 8, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.; Svendsen, G.L.H.; Svendsen, G.T. Are Large and Complex Agricultural Cooperatives Losing Their Social Capital? Agirbusiness 2012, 28, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.R. Basic Cooperative principles and their relationship to selected practices. J. Agric. Coop. 1998, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, H.C. The economic role and limitations of cooperatives: An investment cash flow derivation. J. Agric. Coop. 1992, 7, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.L. The Future of U.S. Agricultural Cooperatives: A Neo-Institutional Approach. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1995, 77, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, M. The future of agricultural cooperatives in Canada. A property rights approach. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1995, 77, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, B. The future of cooperatives: A corporate perspective. Finnish J. Bus. Econ. 1999, 48, 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, G.; Sporleder, T.L. Social Capital in Agricultural Cooperatives: Application and Measurement; Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, R.; Roessl, D. The role of social capital in the development of community-based cooperatives. In New Institutional Developments in the Theory of Networks, Franchising, Alliances and Cooperatives; Tuunanen, M., Windsperger, J., Cliquet, G., Hendrikse, G., Eds.; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.; Kihlén, A.; Norell, L. Are traditional cooperatives an endangered species? About shrinking satisfaction, involvement and trust. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2009, 12, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, Q.; Huang, Z. Benefits and pitfalls of social capital for farmer cooperatives: Evidence from China. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Lu, H.; Deng, W. Between social capital and formal governance in farmer cooperatives: Evidence from China. Outlook Agric. 2018, 47, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, X. Social Capital, Member Participation, and Cooperative Performance: Evidence from China’ s Zhejiang. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Grootaert, C.; Van Bastelaer, T. Understanding and Measuring Social Capital: A Multidisciplinary Tool for Practitioners; Social Capital Working Paper Series; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hail, L. The impact of voluntary corporate disclosures on the ex-ante cost of capital for Swiss firms. Eur. Account. Rev. 2002, 11, 741–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnen, C.M. Business networks, corporate governance, and contracting in the mutual fund industry. J. Financ. 2009, 64, 2185–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, D.; Pritchett, L. Cents and sociability: Household income and social capital in rural Tanzania. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1999, 47, 871–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, L.J.; Siles, M.E.; Schmid, A.A. Social Capital and Poverty Reduction: Toward a Mature Paradigm; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, L.J.; Schmid, A.A.; Siles, M.E. Is Social Capital Really Capital? Rev. Soc. Econ. 2002, 60, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, V.L. Toward a social capital theory of cooperative organisation. J. Coop. Stud. 2004, 37, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Golovina, S.; Hess, S.; Nilsson, J.; Wolz, A. Social capital in Russian agricultural production cooperatives. Post-Communist Econ. 2011, 26, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F.; Modena, F.; Tortia, E. Do cooperative enterprises create social trust? Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingalsbe, G.; Groves, F. Historical Development. In Cooperatives in Agriculture; Cobia, D., Ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 106–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, A.; Miani, M. The long march of Chinese cooperatives: Towards market economy, participation and sustainable development. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2014, 20, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liang, Q. Agricultural organizations and the role of farmer cooperatives in China since 1978; Past and present. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hendrikse, G. Core and common members in the genesis of farmer cooperatives in China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2013, 34, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hendrikse, G.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X. Governance Structure of Chinese Farmer Cooperatives: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Agirbusiness 2014, 31, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.; Woodruff, C. Private order under dysfunctional public order. Mich. Law Rev. 2000, 98, 2421–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, C.; Valentinov, V. Member heterogeneity in agricultural cooperatives: A system-theoretical perspective. Sustainablility 2018, 10, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhler, J.; Kühl, R. Dimensions of member heterogeneity in cooperatives and their impact on organization—A literature review. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2018, 89, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Nilsson, J. Capital Constraints of Farmers’ Cooperatives: From the Perspective of Social Capital Theory. China Rural Surv. 2017, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, S.J.; Hart, O.D. The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).