Dealing with Undeniable Differences in Thessaloniki’s Solidarity Economy of Food

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Meaning of Solidarity (Economy)

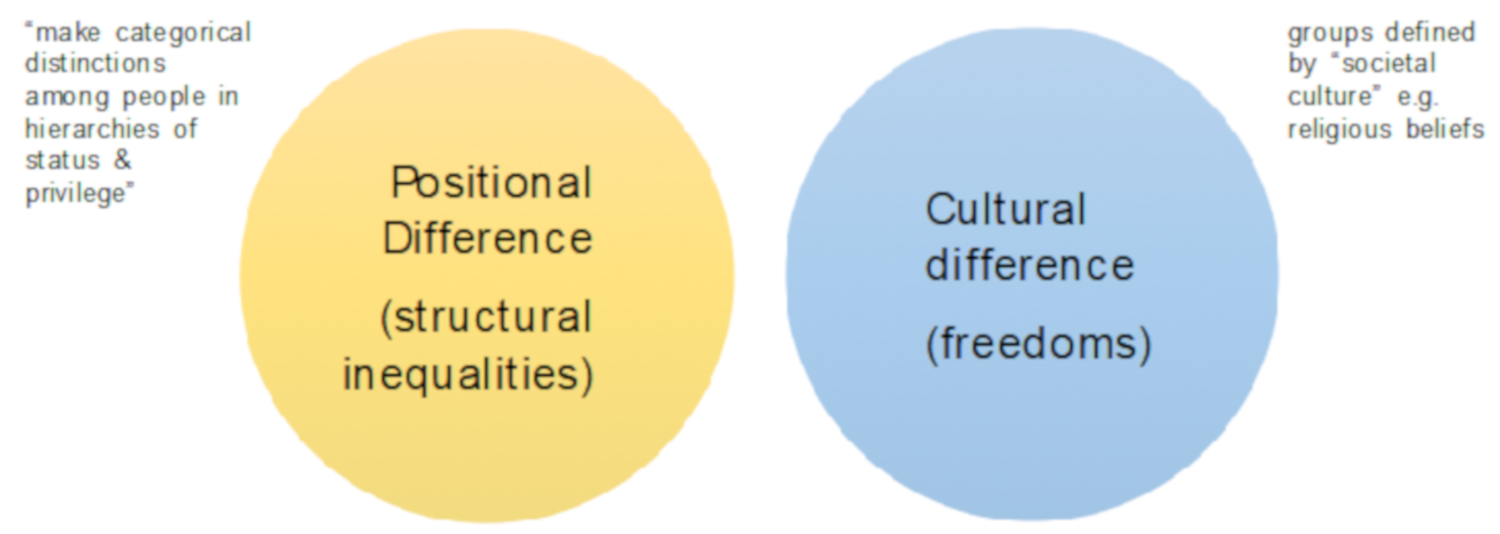

2.2. Examining Tension, Conflict, and Difference

3. Methods

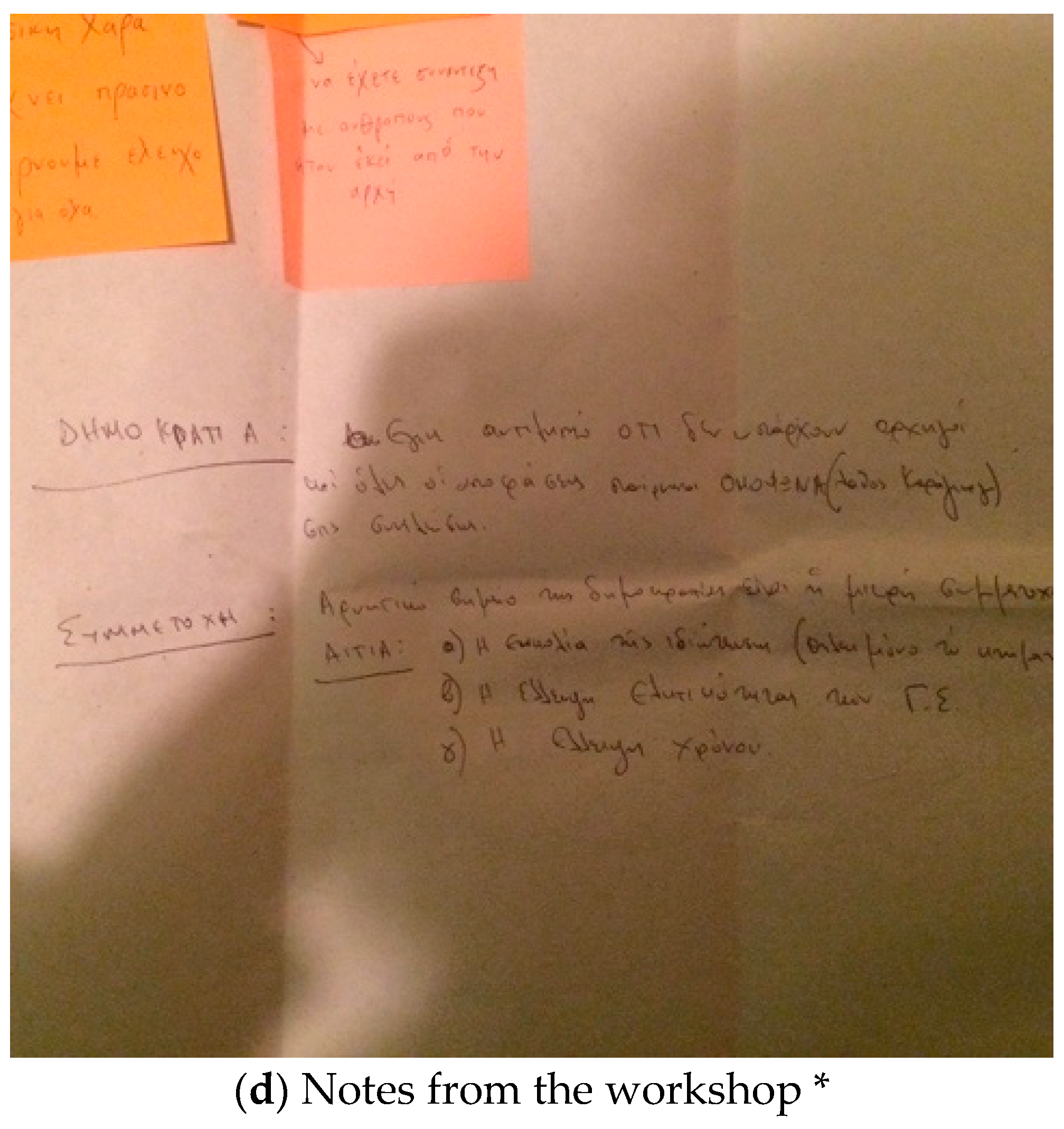

3.1. Participatory Video Group

3.2. Analyzing Conflict

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Motivations of Solidarity-Making

“We don’t want to make philanthropy. Let me give you an example. We have 22–30 families. Half of them cannot participate because they have serious health problems, mental problems, inside their families,…But the other half, they come with us they prepare the distribution they distribute food to other people also, so it’s like sharing the work, and spreading the work…We will invite them and produce with them all together, the products will be consumed by them, by us and by other people who cannot participate. We have to mobilise people, not just to provide them with food, but because we want to give them a perspective for the future”.

“The problems we talked about, they are the same throughout Greece, whether you are within the law, or outside of it, finding understanding between each other is a bit difficult. But the conclusion weighs up in the end, which is where you will find disagreements, the resignations, but nevertheless the initiative carries on, it stood its ground, and there is a recognition today of a wide range of citizens, so to say”.

4.2. Politics of Difference in Context

4.2.1. Material Difference

4.2.2. Positional Difference Influenced by Material and Social Inequalities

“…the old cooperative had to do with money and profits, they were profit, while we are not-for profit, so none of them has as a motivation the money, nobody gets extra money by doing what they do. Which is a basic difference. But it’s the same thing, you put power and it’s the same thing. There are some people who want to be in charge of the cooperative movement of Greece. They want to be in charge for different reasons, they may hope to claim better position governing, cooperative Greece, I don’t know, maybe, I am sure that some of them just want to be the number one lecturer and the number one guy when the media want to discuss with someone about cooperatives”.

4.2.3. Positional Differences Influenced by Ideological Differences

“So all the important decisions were made in closed assemblies, without trying to decide what happened, without inviting the persons involved to give us an explanation of what they did, without trying to warn them, or give them, I don’t know, just tell them, if you do this again we will fire you. So we underestimated forgiveness, cooperation and education and we worked with punishment and power. That bothered me very much and…that’s the reason why many people of the board resigned, because we wanted to discuss about our problems, we didn’t want like a big hammer to smash them all the time”.

“You can’t neglect real life and practicing of a theory. Because ok in theory [a board member] was a member of the cooperative, [a worker] was a member of the cooperative, we have the weekly assembly where everyone can participate with direct democracy, so we have no bother, but you can’t keep the fact that there is also a board of directors, there is also a collective boss, so we would say the assembly, the weekly assembly is the boss of the workers, ok, the workers can participate in the assembly and can influence things, but in the end, a decision has to be made, and some people need to comply with that decision”.

“Yes we said that there is no place for initiatives which employ employees. All employees must be workers and all members should be workers, in order to not have employees…There are people that believe that they are not equals, and they must be employees, that is let’s say the right-wing approach of the cooperative work. The systemic. And some other they believe that the workers must decide for everything and the other members are just sponsors. They put just the money for the cooperative share. Wait a minute. I don’t accept the idea that the workers are my employees. My employees? I am not the boss”.

“The achievement of formal equality does not eliminate social differences, and rhetorical commitment to the sameness of persons makes it impossible even to name how those differences presently structure privilege and oppression”.

“I and many other people of the cooperative think that they don’t work with cooperation anymore, they don’t try to build on different views in order to create the road that the cooperative will take, but they insist on their own view and they isolate all the people with different views than them, so they are more hard than they should be…, and this happens despite them going to the media every other day and saying and declaring how democratic we are how everything is amazing and how equal everybody is. But what they say and what they do is different”.(Orfeas, Bioscoop)

4.2.4. Strategic Differences Influenced by Ideological Differences

“…so we had people from let’s say anti-authoritarian or anarchist movements up to I don’t know the central mainstream PASOK movement, PASOK political party, but all these people used to manage to cooperate and work with each other very well, and that was the main thing that attracted me and made me participate in this effort…we were very confident the first three years, we were all believing we had strong bonds with each other, even with the two opposite sides, we were something like friends, there was big trust between us, and all of this slowly and steadily started collapsing, until we reached this point where no way I cannot trust them. And maybe them me”.(Orfeas, Bioscoop)

“…when he was the leader, or at least one of the leaders in the working group of the quality and compatibility, they always stopped Bioscoop from having Bio.Me products because Bio.Me products don’t have the license. And Bioscoop could have a fine because of that, but we decided that we were willing to take this risk, we need to support Bio.Me and if a fine comes, we will find solidarity, we will find a way to solve it”.

4.3. The “Political” Becomes “Personal”

“The collective spirit is a thorn in our side. Though, we are working hard to improve it. That is to say, even though we say that we are doing things collectively, we can often blow them apart with just one detail. This means that we are not mature, while we say things, we sign things, we do things too, [but] very often we dissolve things”.

5. Conclusions

“…surely it is unrealistic to assume that such decentralized communities need not engage in extensive relations of exchange of resources, goods and culture. Even if one accepts the notion that a radical restructuring of society in the direction of a just and humane society entails people living in small democratically organized units of work and neighborhood, this has not addressed the important political question: how will the relations among these communities be organized so as to foster justice and prevent domination?”

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dacheux, E.; Goujon, D. The solidarity economy: An alternative development strategy? Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2011, 62, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSE Secretariat, of the Greek Ministry of Labour, Social Security and Social Solidarity (2018) Annual Report on SSE 2018. Available online: https://kalo.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/kalo_annualreport2018.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Laville, J.-L. The Solidarity Economy: An International Movement. RCCS Annu. Rev. 2010, 2, 2–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, S. Social and Solidarity Economy and the Crisis: Challenges from the Public Policy Perspective. East-West J. Econ. Bus. 2018, XXI, 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Rakopoulos, T. Responding to the crisis: Food co-operatives and the solidarity economy in Greece. Anthropol. South. Afr. 2013, 36, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steinfort, L.; Hendrikx, B.; Pijpers, R. Communal Performativity—A Seed for Change? The Solidarity of Thessaloniki’s Social Movements in the Diverse Fights Against Neoliberalism. Antipode 2017, 49, 1446–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekeris, C.; Kaberis, N.; Pinguli, M. The Self in Crisis: The Experience of Personal and Social Suffering in Contemporary Greece Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe. Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe; London School of Economics: London, UK, 2015; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Theocharis, Y.; van Deth, J.W. A Modern Tragedy? Institutional Causes and Democratic Consequences of the Greek Crisis. Representation 2015, 51, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzogopoulos, G. The Greek Crisis in the Media: Stereotyping in the International Press; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades, A. At the eye of the cyclone: The Greek crisis in global media. In Greece’s Horizons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Theodossopoulos, D. Infuriated with the Infuriated? Curr. Anthropol. 2013, 54, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzfeld, M. The hypocrisy of European moralism: Greece and the politics of cultural aggression—Part 2. Anthropol. Today 2016, 32, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Capelos, T.; Demertzis, N. Political Action and Resentful Affectivity in Critical Times. Humanit. Soc. 2018, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. The Ideal of Community and the Politics of Difference. Soc. Theory Pract. 1986, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arampatzi, A. Constructing solidarity as resistive and creative agency in austerity Greece. Comp. Eur. Politics 2016, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantzara, V. Solidarity in times of Crisis: Emergent Practices and Potential for Paradigmatic Change. Notes from Greece. Studi Di Sociologia 2014, 3, 261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Karyotis, T. Greece, When the Social Movements Are All That Is Left. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/theodoros-karyotis/greece-when-social-movements-are-all-that-is-left (accessed on 24 September 2015).

- Rozakou, K. Socialities of solidarity: Revisiting the gift taboo in times of crises. Soc. Anthropol. 2016, 24, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodossopoulos, D. ‘Philanthropy or solidarity? Ethical dilemmas about humanitarianism in crisis-afflicted Greece’. Soc. Anthropol. 2016, 24, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arampatzi, A.; Nicholls, W.J. The urban roots of anti-neoliberal social movements: The case of Athens, Greece. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 2591–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvário, R.; Kallis, G. Alternative Food Economies and Transformative Politics in Times of Crisis: Insights from the Basque Country and Greece. Antipode 2017, 49, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. Solidarity Economy: Key Concepts and Issues. In Solidarity Economy I: Building Alternatives for People and Planet; Kawano, E., Masterson, T., Teller-Ellsberg, J., Eds.; Center for Popular Economics: Amherst, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchman, J. Ideas on How Food Sovereignty and Solidarity Economy Fit Together; Background Paper; Coordinating Committee of the Civil Society Mechanism of the Committee for Food Security: Budapest, Hungary, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, S. ‘What Markets Can—and Cannot—Do’. Challenge 1991, 34, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. Realizing justice in local food systems. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakopoulos, T. The crisis seen from below, within, and against: From solidarity economy to food distribution cooperatives in Greece. Dialect. Anthropol. 2014, 38, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakopoulos, T. Solidarity, Ethnography and the De-Instituting of Dissent. J. Mod. Greek Stud. Occasional Paper 6. 2016. Available online: https://www.press.jhu.edu/journals/journal-modern-greek-studies/occasional-papers (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. A Postcapitalist Politics; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E. Other Economies are Possible! Organizing toward an economy of cooperation and solidarity. Available online: http://www.dollarsandsense.org/archives/2006/0706emiller.html (accessed on 4 January 2019).

- Anderson, C.R. Growing Food and Social Change: Rural Adaptation, Participatory Action Research and Civic Food Networks in North America. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Structural Injustice and the Politics of Difference; University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Plush, T. Fostering social change through participatory video: A conceptual framework. In Handbook of Participatory Video; Milne, E.-J., Mitchell, C., de Lange, N., Eds.; Altamira Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Herr, K.; Anderson, G.L. The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pasmore, W. Action Research in the Workplace: The Socio-technical Perspective. In Handbook of Action Research. Participatory Inquiry and Practice, 2nd ed.; Bradbury, H., Reason, P., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, P.; Agyeman, J. Urban food sharing and the emerging Boston food solidarity economy. Geoforum 2019, 99, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiven, M.; Khasnabish, A. The Radical Imagination; Zed Books: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Utting, P. (Ed.) Social and Solidarity Economy. Beyond the Fringe? Zed Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Packard, J. “I’m Gonna Show You What It’s Really like out Here”: The Power and Limitation of Participatory Visual Methods. Vis. Stud. 2008, 23, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindon, S. Participatory video in geographic research: A feminist practice of looking? Area 2003, 35, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madianos, M.G. Suicide, unemployment and other socioeconomic factors: Evidence from the economic crisis in Greece. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2014, 28, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hahnel, R. Economic Justice and Democracy: From Competition to Cooperation; Routeledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McAlevey, J.F. No Shortcuts. Organising for Power in the New Guilded Age; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, D.M. The Greek economic crisis as trope. Focaal 2013, 65, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Initiative | Semi-Structured Interviews | Events | Fieldnotes—Ethnography/Informal Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perka | 9 × single 1 × group (2) | Film screening and discussion Assembly discussing statute 2 × festivals Mapping at festival | Dinners at APAN social centre Discussions whilst gardening at Perka 2 Informal chats with friends |

| Bioscoop | 5 × single (1 repeat) 1 × group (2) | Anniversary celebration event | Informal discussions with members |

| Koukouli | 2 × single | Attended event at the shop | Informal discussions at store |

| Producers/activists involved in other initiatives | 4 × single 2 × group (2) | Consumer–producer event at Mikropolis Pervolarides events Katerini/Thessaloniki ecofestivals | Farm visit to Giannis Discussions about collaboration at Ecofestival |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buchanan, C. Dealing with Undeniable Differences in Thessaloniki’s Solidarity Economy of Food. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082426

Buchanan C. Dealing with Undeniable Differences in Thessaloniki’s Solidarity Economy of Food. Sustainability. 2019; 11(8):2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082426

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuchanan, Christabel. 2019. "Dealing with Undeniable Differences in Thessaloniki’s Solidarity Economy of Food" Sustainability 11, no. 8: 2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082426

APA StyleBuchanan, C. (2019). Dealing with Undeniable Differences in Thessaloniki’s Solidarity Economy of Food. Sustainability, 11(8), 2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082426