Abstract

Current serious environmental issues, such as deforestation, compel compulsory school education on the need for reflection on pedagogical practices to promote education for environmental sustainability. The educational process about the “tree as living being” requires that content and attitudinal dimensions be deeply integrated. Therefore, meaningful learning of biological similarity—between tree and animal—needs to be prioritised. It will promote the development of tree protection attitudes. Under this approach, an action research was developed to contribute to a future primary teacher education model. A didactic-pedagogical intervention was designed. It was implemented to assess the educational potential of infrared thermography in the development of ecocentric education. A group of students attending the 3rd year of primary education participated in this qualitative case study. The results revealed that ecocentric conceptions were constructed bringing these children closer to scientific knowledge. It resulted in the development of conservation/protection tree attitudinal learning. It is also worth mentioning the contribution of this study to (re)think (re)construction of the formative process of future primary teachers in order to: direct the teaching–learning process to environment real problems; and to promote the necessary debate on the contribution of technology to achieve innovation of pedagogical practices.

1. Introduction

Worldwide ecosystem deforestation has led to local and global environmental imbalances, to the point of compromising the present and future of the ecosphere. Human behaviour has significant involvement in the breakdown of balance in ecological interrelationships. The environmental impact leaves humanity with troubling challenges, which require a commitment to the search for urgent answers and solutions. In this scenario, compulsory schooling can play a relevant role. “Education is the action we perform on the people with the purpose of enabling them to become society members in an integral, conscious, efficient and effective way; education allows them to give value to the acquired contents, applying them directly to their daily life, that is, to act as a result of the assimilated educational process” [1] (p. 109).

Thus, the educational process is a challenge. It needs to be renewed permanently. Therefore, it is necessary to debate this subject. There is a need to develop a reflective spirit to scrutinise everyone stages of the teaching-learning process. There are plenty of references to guide this process [2,3].

Education research has increasingly shown concern about the connection between teacher and teaching–learning process quality. It is emphasized the need for teachers to develop reflection and research skills during their pedagogical practices [4]. The development of research capacities and reflection during pedagogical practices of education students contributes to make them change agents. This is because these capabilities will impact their own teaching-learning process [5].

Both scholar curriculum and program of the educational system also intervene in this context because it is the teacher that operates them (curriculum and program developer).

The Portuguese educational system (Law no. 46/86 of October 14, art. 7: 3069) states that the 4 years primary education is universal, compulsory and free [6]. The curriculum of Portuguese elementary education encompasses the following areas: Portuguese, Mathematics, Study of the Environment, and Artistic and Motor Expressions. It is aimed for the child to acquire the bases of scientific, technological and cultural knowledge, which will enable them to understand nature and its insertion in society. The basic education is governed by a formal curriculum and each area has its own syllabus. The document Curricular Organization and Programs of the Study of the Environment Curriculum Area begins with the assumption “Children of this age level perceive reality as a globalised whole” [7] (p. 101). It states as guiding principles: “Study of the Environment is the curriculum area that groups concepts and methods of various scientific disciplines such as History, Geography, Natural Sciences, Ethnography, and others. It contributes to the progressive understanding of the interrelationships between Nature and Society. On the other hand, Study of the Environment is at the intersection of all other areas of the education program, being the motivation for learning these areas” [7] (p. 101).

A pedagogical objective of the Study of the Environment curriculum area is to know the concept of what a being is living, and to understand the ecological relations of existing living beings in natural ecosystems. Several studies [8,9,10] have verified the principle at the beginning of schooling: the educational process in the science area is based on the search of explanation from the environmental surroundings. It gives the child the ability to give meaning to the construction of concepts; when these conceptions form part of the child, they condition their way of thinking and acting. It is a motivating educational challenge in formal compulsory education to engage children in the identification of causes and the search for solutions to current serious environmental problems. It is about building a concept of nature not confined to biology but coupled with the joint perception of environment and humanity. It is directed to a necessary social transformation. It has been demonstrated that the ecosphere faces serious sustainability risks. So, it is urgent to develop competencies to enable the exercise of critical, reflexive and committed citizenship with an ecocentric attitude in the face of nature. That is, the child must understand that he/she is an integral part of the ecosphere, like all other living beings; the child depends on nature and cannot have only a utilitarian conception of nature (anthropocentric conception). When the child acquires an ecocentric conception, these children should be encouraged to contribute with their attitudes and practices in order to find answers and solutions to environmental problems. Ecocentrism is described as the degree to which individuals become aware of and engage in the search for solutions to environmental problems [11]. An educational process capable of developing these competencies, based on respect for socio-cultural differences and synchronised with a pro-intervention role contributes to ecosphere sustainability. Therefore, it will contribute to the exercise of pro-environmental citizenship. Scientific literacy and citizenship are intertwined in the learning of sciences, so it is a necessity of society. Sciences learning from the socio-constructivist approach [12] points to the need to develop in future teachers, both personally and professionally, skills that allow them to respond to recurrent educational challenges. However, today’s environmental problems, particularly those arising from human interference against interdependencies and interrelations of the environment, are challenging. Teaching science is teaching students to (re)build their own knowledge and to position themselves as committed environmentalists in an ecocentric society [2].

It is expected that higher education pedagogical education will include the development of skills for teachers to be reflective, evaluative, and critical. New teachers will be resourceful to review constantly their pedagogical practices and to motivate themselves for innovation search [13]. The articulation between reflection and investigation on the teaching process improves the performance of the teacher himself and increases a student’s motivation [14].

The Portuguese legal system of qualification of primary education teachers establishes that supervised teaching practice (STP) is the initiation to professional practice. The STP includes conceptual and procedural knowledge of the curriculum. The STP is a pedagogic training. The curricular STP should be a means of promoting the autonomy of future professionals; it provides social and personal training for integrating information, methods, techniques, knowledge, skills, attitudes and scientific, pedagogical and social values according to the teacher’s role [15]. It is a means to expose the future teacher to a vocational learning context in a gradual and targeted manner, and it is the environment to develop teaching skills. From this perspective, the teacher professional development integrates the following dimensions: research–action–training [16]. In this sense: “The quality of teacher education is shown when the teaching activity is carried out. The quality has direct effects not only on students’ level of knowledge but also on their personality, particularly in the early years of their school experience” [17]. This should be even more important in the training of future primary teachers. The new teacher needs to understand the relevance of children’s ecocentric education as a way to develop valuation and environmental preservation attitudes; these attitudes are the basis of sustainability. Thus, this research is based on the following premises:

- (i)

- The pedagogical model of teacher education influences the construction and operationalisation of the teaching–learning process.

- (ii)

- The teaching of sciences in the curriculum area of Study of the Environment must be linked to real problems of the environment.

- (iii)

- Deforestation of the ecosphere is a major environmental problem.

- (iv)

- The didactic resources and dialectical methodology of the teaching process condition students’ learning.

Didactic resources and their didactic exploration are particularly relevant when it comes to teaching and learning complex scientific concepts. If the didactic resource “image” manages to show the “hidden world” of living beings, it may be a relevant pedagogical resource in the teaching of complex concepts that imply abstraction. Thermograms—images obtained through infrared thermography technology (IRT)—allow us to observe in a real way the particularity of this “hidden world” of living beings. The temperature (“hidden world”) is also a physiological characteristic of the tree. Based on thermal radiation emitted by objects, the IRT is a non-destructive, non-contact and sustainable (non-waste-generating) diagnostic technique that allows the evaluation of surface temperature [18].

Considering the above, this study was carried out in the context of STP in primary education. It focuses on the teaching of science, specifically in the Study of the Environment area. It follows the socio-constructivist approach to learning. It seeks to develop an enhanced meaningful learning about “the tree is a living being”. It resorts to temperature as a physiological characteristic common to living beings. This is a supervised study carried out in the classroom and the technology laboratory of a university. The data analysis evaluates didactic-pedagogical intervention based on the IRT application.

This supervised educational research is part of the studies that we have been developing in Teachers for Primary Education and Childhood Education Course of an Institution of Higher Education.

Problem and Objectives

The research questions of this study are:

Q1: Does infrared thermography applied to trees actually contribute to the ecocentric education of children attending primary education?

Q2: Does the training of the reflective/research teacher prepare them to use IRT in the ecocentric education of children?

The objectives of this research are:

(a) To construct, apply, and assess an infrared thermography (IRT) didactic–pedagogical intervention (DPI) on concepts related to “the tree is a living being”.

(b) To understand the effectiveness of the training of the reflective/research teacher in their competence in the use of IRT in ecocentric education in science.

2. Background

Serious environmental problems have long threatened the balance of natural ecosystems, endangering ecosystem sustainability. It is a troubling problem “to meet the needs of present generations without compromising the possibility of future generations being able to meet the needs of the future” [19] (p. 43). Education plays a decisive role in the reorientation of humanity through the development of the necessary social sensitisation [20]. Education must be focused on the real world [21]. In the context of education, the school is expected to integrate real problems of environment and society in the curriculum. The teacher is asked to be a guide and facilitator of this learning. The school is the propitious institution to educate in this sense.

The Portuguese Primary Education Curriculum highlights the role of science education in the development of skills to respond to current complex environmental problems. Joaquim Sá [22] (p. 29) says: “Science has a dynamic structure, and it is in permanent evolution; it constitutes a privileged instrument of stimulation of the human spirit; it is important for ordinary people as an integral part of their intellectual development in view of understanding the world we live in, and the ability to critically solve today’s increasingly complex problems”.

In the socio-constructivist perspective of science learning, it is essential to debate the conceptual perspective of teaching. The (re)construction of conceptions in the teaching processes is proposed. In the perspective of several researchers, school curriculum should provide the construction of scientific knowledge (socio-constructivist design) through meaningful learning [23,24,25]. According to Significant Learning Theory, this learning is conditioned by teaching strategies options as well as of evaluation strategy. This last one constantly calls the attention of the teacher to the challenge “How to teach?”. The teacher is committed to knowing what the student knows about what is intended to teach; and to adapt the strategies to this context [26]. It is highlighted that the student needs to be actively and emotionally involved in the (re) construction of their knowledge [12]. The application of this pedagogical strategy allows the student to develop a set of competencies that promote their autonomy, such as cooperation and critical thinking [27]. But for this to happen, the teacher has to adapt his teaching strategy: the teacher guides and motivates at the same time, and this process requires the teacher to have reflective and investigative capacities.

In this study, teaching linking with real contexts of environmental problems poses the challenge of developing a new proposal for learning about the tree. In fact, it is considered that formal education has responsibilities in the ecocentric education of children. The task is to contribute to sustainability by means of changing the mindset from a human being (anthropocentrism) on the centre of life to perceiving the nature as the whole (biocentrism and ecocentrism) [28]. The environment is not only a concern of environmentalists. It should occupy a prominent place in the ordinary citizen’s consciousness. In this way, the involvement and awareness of everybody in the free and informed choice for responsible environmental behaviours is emphasized. In Portugal’s National Environmental Education Strategy 2020, it says “individual, and collective choices and behaviours contribute to a healthier environment for human life” [29] (p. 15). From an early age, individuals should be sensitized to the development of pro-environment sustainable actions [30].

This behaviour can be greatly influenced by the teacher because they have a relevant role. The teacher’s attitude in the teaching–learning process is a conditioning factor for students’ motivation, interest and commitment [31]. The attitudes are fixed and acquired; there is an association between attitudes and behaviours [32]. The teacher should conceive the curriculum to build knowledge interconnecting with the acquisition of skills [8]. The process of teaching underlies a set of methodological options, strategies and didactic resources. The role of the teacher in this whole process is crucial. Determinants are the choices of the teacher to achieve the educational objectives and their operationalisation. The teacher decisions feedback the next decisions; it conditions the success of the teaching–learning process. The teacher is the mediator of science curricular learning; therefore he/she requires an integrative attitude. The teacher should combine the instructional dimension with the educational dimension. The teacher will seek to make science conceptual curricular learning inseparable from the development of pro-environment attitudes. The teacher is the group member who observes and interprets the actions and manifestations of each child and the group as a whole. The teacher is able to create a culture in which the learning of sciences is linked to awareness, evaluation capacity and pro-active personal desire about environmental problems. That is, the teacher joins curricular conceptual learning to the construction of attitudes directed to socio-environmental transformation. That is, the teacher promotes science education committed to attitudes of environmental citizenship.

Each science teaching situation is idiosyncratic. Teaching and learning about “the tree is a living being” at the same time that the development of an ecocentric perspective is pursued is complex. It is about a biological entity integrated in an ecocentric conception, which requires protective attitudes, all this under equal rights vision. It is an educational action of great complexity. Moreover, the challenge increases when students attending primary education are at the stage of concrete operations [33]. Moreover, society does not perceive yet that humans are living beings as part of nature. Nor is it still accepted that this living being needs social practices based on egalitarian respect, be it animal or tree. This is why the lessons are prepared to face the environmental problems of tree destruction, that is, to facilitate the development of proactive environmental individuals. It is clear that the didactic resources and its exploitation will play a key role.

Of course, if the didactic resource “image” allows the “hidden world” of living beings to be seen, it constitutes a relevant pedagogical resource in the teaching of Study of the Environment. However, thermal images obtained by IRT allow us to observe particularities of the “hidden world” of a living being. Therefore, they are a promising resource in the teaching of complex and imbricated abstract concepts to children at the stage of concrete operations.

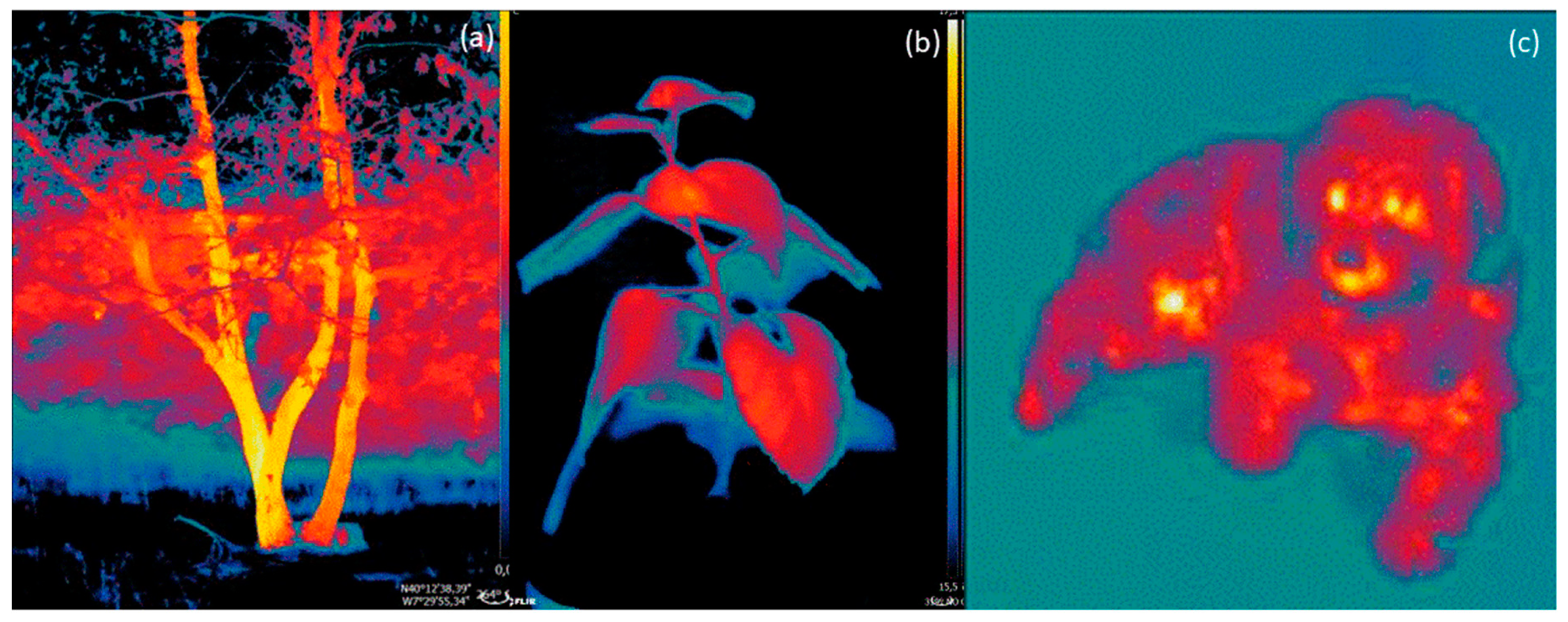

Infrared thermography is a generic term for a variety of techniques that allow the visualisation of the surface temperature of objects on a map. This technology is already widely and successfully used in several domains. Nevertheless, its application to tree monitoring is recent. The temperature distribution in the “living tree” results from the thermal balance between the metabolic heat generation and the exchanges with the environment. The application of IRT to trees requires the reading of several parameters that influence the emissivity of the temperature: apparent, reflected and reflective temperature that vary as a function of the angle between the chamber and the tree surface, and the direction of the incidence of the radiation coming from the environment and the incidence of solar rays [18,34]. In the thermographic record, it is required a strong thermal contrast; that is, there must be a difference of radiative power between the environment and the object under analysis [35]. Despite the necessary rigour of the application of IRT to the tree, some conditions are required to transform the thermogram into a didactic resource, that is, to be a facilitator of teaching–learning. The didactic adaptation of this technological resource (the thermograms) as a tool in a dialectic methodology in the teaching–learning process will certainly be demanding to the teacher.

The teacher naturally has didactic resources which they are already familiar with for the application in his routines. However, it is necessary to question the suitability of these routine practices. Are they able to respond to serious socio-environmental challenges? The resources must be adequate, innovative, motivating and facilitating of a teaching–learning process that seeks to integrate real contexts of the local and global environment into the curricular content of science. Does it thus contribute to the necessary social transformation in relation to the interaction with nature? In this line of questioning, teacher education requires debate and innovation of pedagogical practices of science teaching. In fact, science teaching needs to be prepared for socio-environmental problems challenges; it has to be a promoter of the exercise of citizenship anchored in ecocentrism.

The pedagogical model that promotes debate and motivation develops in the teacher the role of teacher-researcher. The teacher can play a central role in the innovation of sciences educational practices in the case of Study of the Environment area. They will be able to contribute to a socio-environmental transformation through the integration of scientific literacy and ecocentric education. In PISA [36] “scientific literacy is defined as the ability to understand the characteristics of science and the significance of science in our modern world, to apply scientific knowledge, identify issues, describe scientific phenomena, draw conclusions based on evidence, and the willingness to reflect on and engage with scientific ideas and subjects. Student’s should be able to apply a scientific approach to assessing scientific data and information in order to make evidence-based decisions”. This seeks to contribute to the development of citizenship attitudes for the preservation of the tree approaching the living being from an ecocentric vision. It is learning based on constant questioning of what is observed and experienced. The notion of competence is shared as “knowledge in use”, as opposed to “inert” knowledge [37]. That is, being competent requires the mobilisation of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values. These dimensions influence how each individual act to solve problems and make decisions [38].

3. Materials and Methodology

3.1. Equipment

We used a FLIR thermal camera, model T1030sc; FLIR MR 176 moisture meter with thermo-hygrometer for determination of atmospheric conditions (temperature and relative humidity). Software used to treat thermograms were FLIR Tools + and ResearchIR Max 4. The colour pallet used in thermograms was LAVA. The thermal camera was connected to the projector during the Lesson in the Technology lab.

3.2. Photographs and Thermograms

Human presence in the natural landscape (didactic script (DS) n-1-).

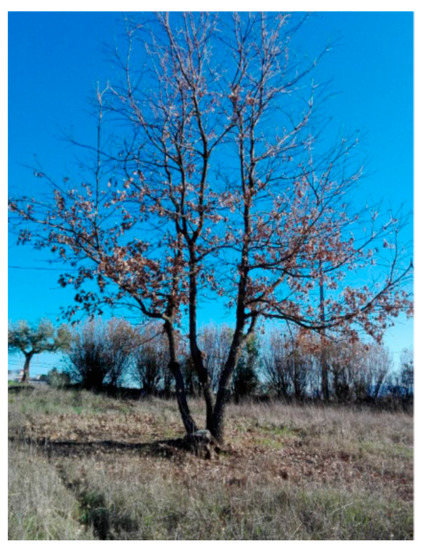

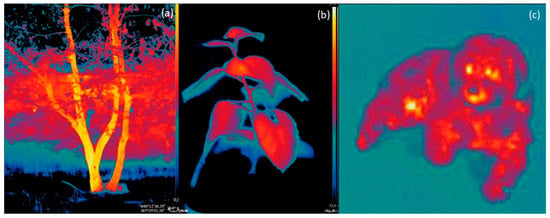

Tree of the species Quercus pyrenaica Willd (didactic scripts n-2 and n-4). It is an autochthonous species of the natural ecosystem from the region where the participating children came from. In order to avoid interfering with the measurement of temperature by the possible excess of water, these thermograms were obtained after several days without precipitation in the region. The thermograms and photographs were collected during the day, at the end of January, in the winter of the Northern Hemisphere.

Potted plantlet of the genus Hibiscus from Portugal (didactic script n-4);

Potted plantlet of the genus Malus;

The dog (didactic scripts n-3 and n-4).

3.3. Methodology

This supervised research is interpretative with participant observation [39]. This is a qualitative case study. It was developed as a DPI framed epistemologically in the learning socio-constructivist approach. This was an action-research study [40,41,42] as is required in the master’s course of pedagogical education in science for primary education. It was carried out in STP of the professional master’s degree course. The planning–action–observation–reflection model was applied throughout the investigation. In this regard, says that professional development submits itself to the action-research-training triad; it is representative of the whole reflective process [16].

It is a small-scale intervention that is part of the project “Advanced Monitoring and Maintenance of Trees”.

3.4. Participants

Tree researchers participated in the research; one of them was at the STP of the master’s degree program for teaching in primary education (future primary teacher) of an Institution of Higher Education. A group of 26 children, 46% female and 54% male, aged between eight and 10 years participated in the study. These children attended the 3rd year of schooling in a public elementary school in a Portuguese city, where the STP was carried out. This primary school established an agreement with the Institution of Higher Education to develop the STP. This supervised educational research is part of the activities that we have been developing in Teachers for Primary Education and Childhood Education Course of the Institution of Higher education.

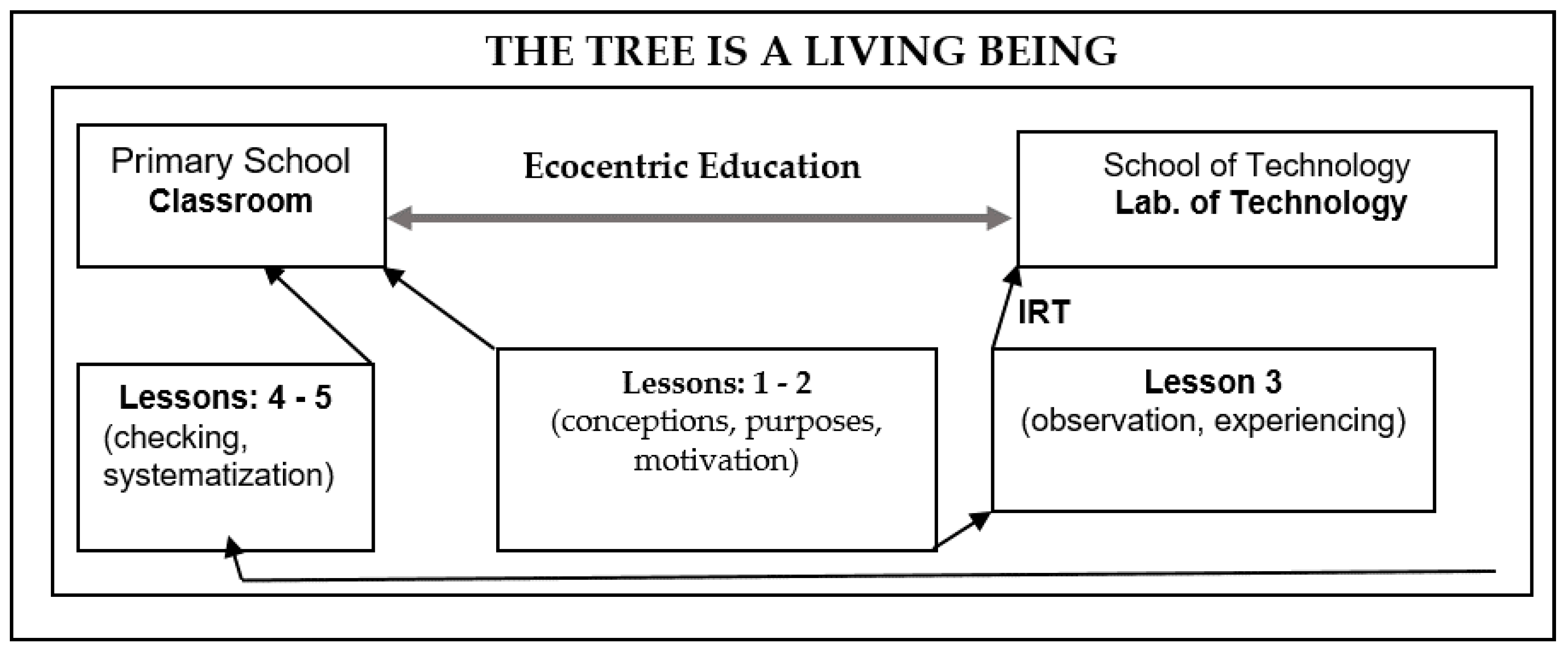

3.5. Contexts of Action

The DPI was carried on the primary school classroom and the technology laboratory of the university of the city where the primary school is located too.

3.6. Data Collection

The instruments used to collect the results of learning were:

(i) Participant observation and direct observation. The “observation allows the recording of events, behaviours and attitudes, in their own context and without changing their spontaneity” [43] (p. 109);

(ii) Written records (made by the children filling the didactic scripts).

Taking into account the premises and objectives described above, two categories of analysis were defined for the analysis of the DPI results. They were defined a priori:

(a) Teaching methods and didactic resources: whether the options taken to structure the DPI methodology, whether the didactic use of IRT thermograms are effective in the integration of scientific literacy and ecocentric education.

(b) Science–technology–tree–society integration: we tried to analyse if the use of technology in the DPI enables the conceptual learning of “the tree is a living being”. It was approached under an ecocentric conception that considered: the biological similarity and equal rights perspective, interconnection associated to the development of attitudes towards tree preservation, the creation of a social need as a real daily problem.

The performance of STP student was recorded. The data collection was carried out by direct and participant observation carried out by the STP pedagogical supervisor.

3.7. Design of Didactic–Pedagogical Intervention (DPI)

The work was divided into three phases.: Pre-action phase; Action phase; Post-action phase

3.7.1. Pre-Action Phase

Objectives: analyze the curriculum content about “the tree is a living being”; design didactic scripts adjusted to the selected class.

The construction of the didactic scripts resulted from the analysis to the curricular framework of “the tree is a living being” concept. It is a component of the “Living beings of each environment” sub-area of the Study of the Environment area [7]. It was found that the sub-area is taught all along the four years of primary education. This sub-area includes concepts of living being, tree care, life cycle, diversity and food chains.

It was observed that in compulsory primary education, the curriculum area of “Study of the Environment” is clear in relation to the educational path of the expected learning about “the tree as living being”. It states that the tree is a natural resource to preserve; and education should promote attitudes related to environmental sustainability through “enlightened and active participation in solving environmental problems” [7] (p. 127). What is described above was included in the lesson (was given of the classroom teacher) before STP took place.

Four didactic scripts were designed.

Photographs and thermograms obtained by IRT were utilized. These resources were means to motivate the interest of the students, to promote the generation of new concepts and to consolidate what was learned. Its construction resulted from the analysis to the curricular framework of “the tree is a living being” concept. It is a component of the “Living beings of each environment” sub-area of the Study of the Environment area [7]. It was found that the sub-area is taught all along the four years of primary education. This sub-area includes concepts of living being, tree care, life cycle, diversity and food chains.

It was observed that in compulsory primary education, the curriculum area of “Study of the Environment” is clear in relation to the educational path of the expected learning about “the tree as living being”. It states that the tree is a natural resource to preserve, and education should promote attitudes related to environmental sustainability through “enlightened and active participation in solving environmental problems” [7] (p. 127). What is described above was included in the lesson before Phase I took place.

3.7.2. Didactics Scripts

The following is a description of the didactic scripts designed for this study.

(A) Didactic script n-1—“What I know about what living beings are…”

The didactic–pedagogical options to design the didactic resources were taken according to the objectives of the Study of the Environment area of 1st, 2nd and 3rd year of primary education, specifically in relation to the content “the tree is a living being” [7]. It also took into account the time at which the DPI was to be carried out and the characteristics of the class. The formative assessment [44] included in this didactic script (DS) is based on the socio-constructivist approach; that is, it is focused on improving learning. According to the script, photography was used by the class as a didactic resource to understand better what living beings are.

The didactic script included a photograph of a natural landscape that shows a human presence (Figure 1). The students wrote down their conceptions, opinions and attitudes. They answered sequentially to the following questions: “(a) Which are the living beings in the photo? Justify your answer. (b) Are there only living beings? Justify your answer. (c) What is a living being? We must all protect nature, but animals should be the first to be protected. Do you agree? Justify your opinion “.

Figure 1.

Photograph of human presence in a natural landscape.

(B) Didactic script n-2—“Let’s explore: the tree is a living being?”

Unlike the DS nº1, the DS nº2 is directed to the ideas: the tree is a living being and is urgent to protect, and biological similarity exists between living beings as in the case of tree and pet. This DS was built up considering it as a fieldwork tool to prepare the class for a visit to the technology laboratory. This DS performs as a field study tool to record the concepts developed in the DPI.

Using the photograph of the tree of the species Quercus pyrenaica Willd (Figure 2), the students recorded their conceptions, attitudes, and expectations and motivations in writing. They answered sequentially the following questions: “1. Explain what a tree is?; 2. The larger tree has dry leaves. Is it a normal condition? Yes or No (Please tick off your idea) Explain your idea; 3. Is the tree a living being? Yes or No (Please tick off your idea) Justify your idea; 4. How could you know if your ideas about the trees are right? 5. Would you like to go to the technology laboratory of the polytechnic institute to know if your ideas about the trees are right? Why?”

Figure 2.

Photograph of the tree Quercus pyrenaica Willd.

(C) Didactic script n-3—“Let’s explore: The dog is a living being?”

Using the photograph of a pet (a dog in Figure 3), the students wrote their conceptions, ideas, attitudes, expectations, and motivations. They answered sequentially the following questions: “1. Explain what a dog is. 2. Explain what a pet is. 3. Is the dog a living being? Yes or No (Please tick off your idea). Explain your idea. 4. A difference between the dog and the tree is that dogs can get sick, but the trees never get sick. Do you agree? Yes or No (please tick your answer). Why? Explain your answer. 5. How would you know if your ideas about the dog are right? “

Figure 3.

Photograph of the dog.

(D) Didactic script n-4—“Let’s answer: When I used IRT I observed and learned:“

The thermograms used were: tree of the species Quercus pyrenaica Willd (Figure 4a), the plantlet of the genus Hibiscus (Figure 4b) and a dog as an example of pet (Figure 4c). The students wrote their conceptions, ideas, attitudes, expectations and motivations. They answered sequentially the following questions: “1. The tree and the dog have a similar characteristic. Can you tell what the characteristic is? 2. The images below are taken from to living beings that you studied in the technology laboratory of the polytechnic institute of your city. Write the description under each image. 3. Why do we say that all the images in Question 2 are taken from living things? Explain what you learned in the lab. 4. How do we know if the dog or tree is sick? Explain what you have learned. 5. What did you learn in the lab that helps you to clarify your ideas about trees? Explain your opinion. 6. Trees are living beings that need our protection. Explain your opinion”.

Figure 4.

Infrared thermography technology (IRT) thermograms: (a) tree of the species Quercus pyrenaica Willd; (b) plantlet of the genus Hibiscus and (c) the pet chosen is a dog.

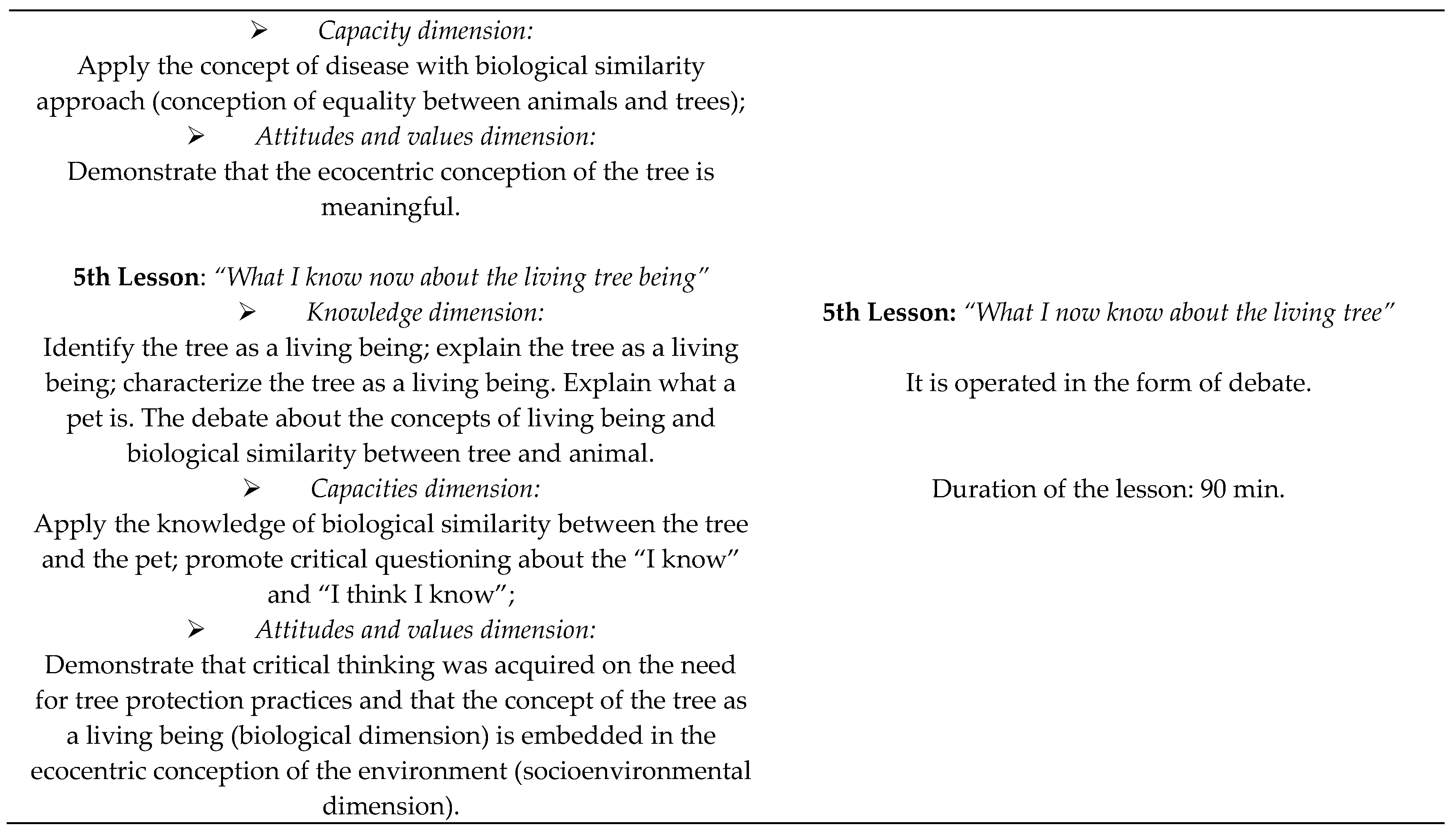

3.7.3. Action Phase and Post-Action Phase

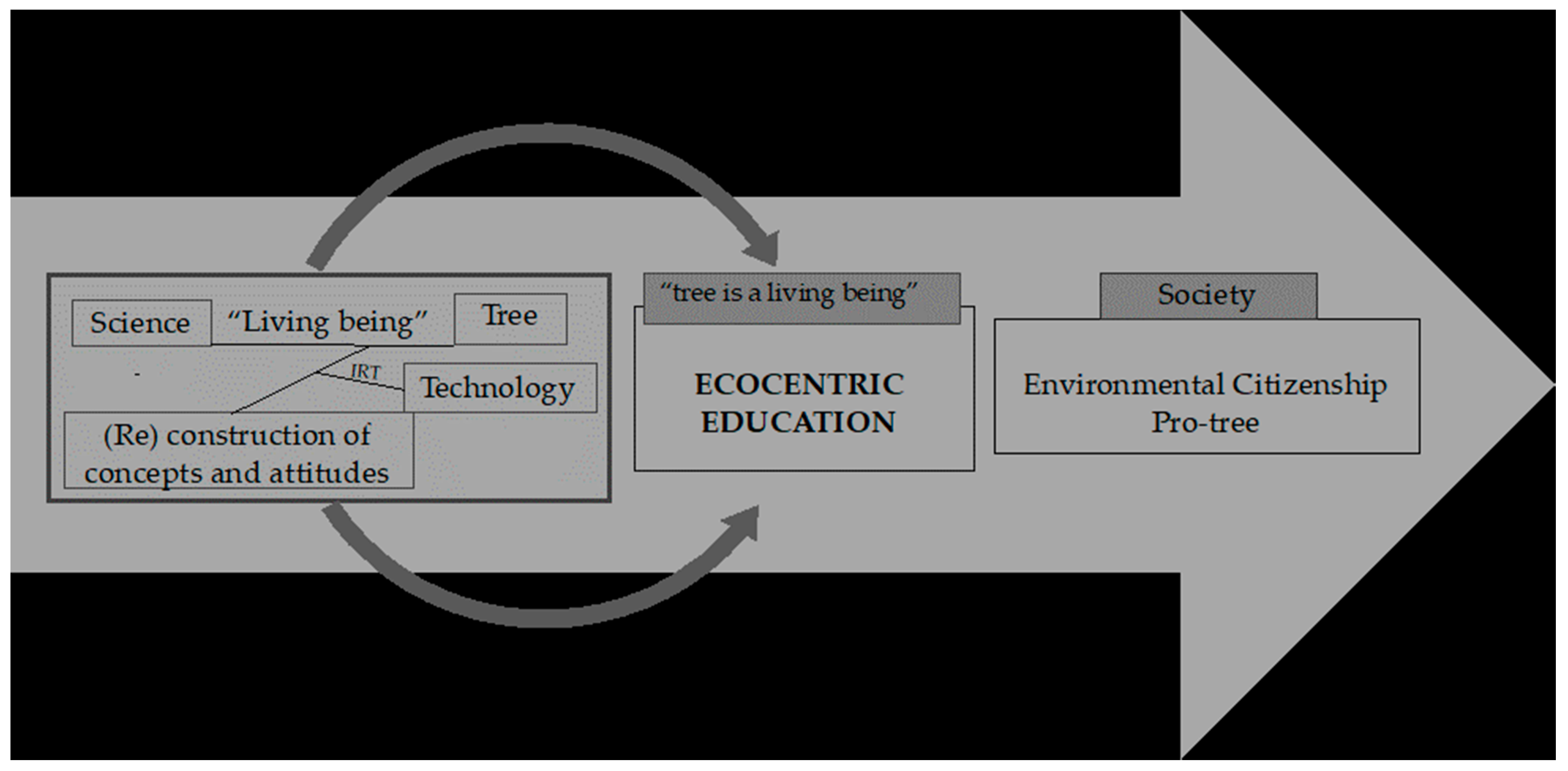

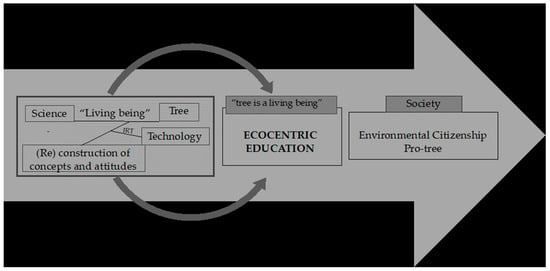

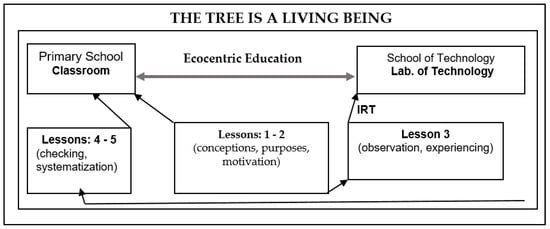

These phases were interrelated. They are related to the structure and development of the didactic-pedagogical intervention. The DPI to relate science-technology-tree-society (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Scheme of the relations between science–technology–tree–society in the didactic–pedagogical intervention (DPI).

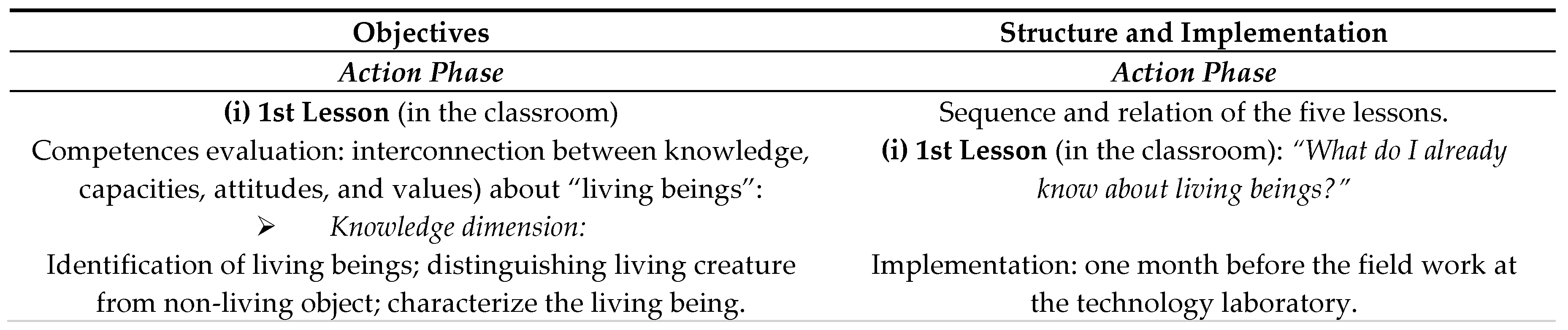

Table 1 shows the relationship between objectives (knowledge dimension; capacities dimension; attitudes and values dimension), structure (2 interrelated phases), implementation and the expected relationship between scientific literacy and ecocentric education. The attitude was the preservation/protection of the tree.

Table 1.

Didactic–pedagogical intervention interrelated phases.

The DPI described above is based on the conceptual scheme of Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Conceptual diagram of the didactic–pedagogical intervention.

Learning (conceptual dimension) is as important as the teaching-learning process itself, and commitment requires values and motivation for socio-environmental intervention. All of them interact with the student to give meaning to what has been learned. The teacher’s attitude conditions the attitudes of the students in relation to what is taught [31]. In this teaching experience, it was considered that the attitudes in the classroom should be given primacy to registration of concepts, exploring cognitive conflict, concept contextualization in everyday social life, motivation, reflection on the impact of human practices in relation to the tree, and to emphasize to the urgency in the change of attitudes.

The lesson carried out in the lab was under the control of the teacher of the lab, and the interactive dialogue was given priority in the communicative approach with the class (Table 2).

Table 2.

The work at the lab of Technology (field work).

4. Results and Discussion

The results and discussion were into two parts: (I) Ecocentric education of children (potentialities of the IRT); (II) Training of the reflective/research teacher (competence in the use of IRT).

4.1. Ecocentric Education of Children (Potentialities of the Infrared Thermography Technology (IRT))

We chose to analyze each lesson. Two categories of analysis were combined: teaching methodology and didactic resources; and science-technology-tree-society relation.

4.1.1. Lesson—“What I Already Know about What Living Being Is”

Using the interactive dialogue, all the children expressed their willingness to say their opinions about the questions posed (listed in DS n-1)) referred to the projected photograph. The children were invited to record in the script (it was distributed at that moment) their ideas on “What I already know about living beings”.

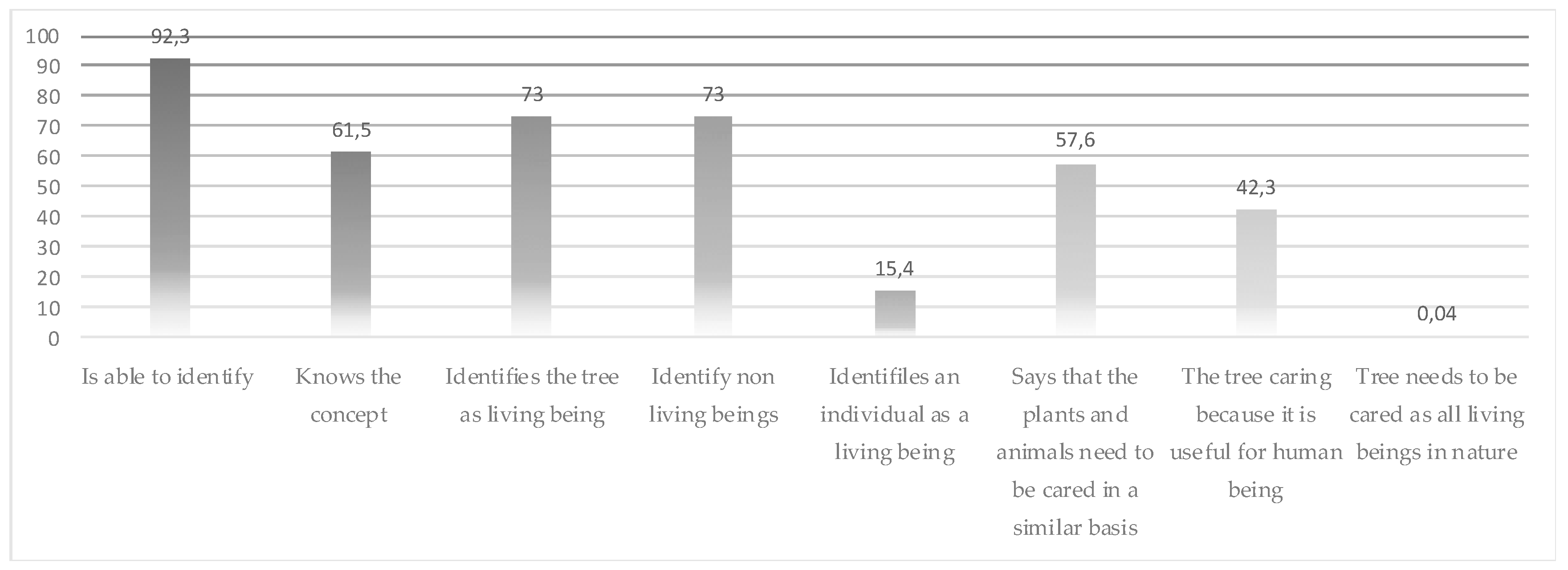

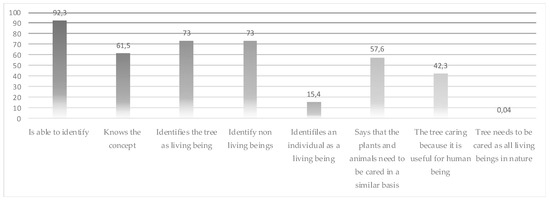

From the analysis of the records made by the children in DS n-1 (Figure 7), only 4% of these children referred to the need to protect trees as all living beings as nature deserves (ecocentric conception).

Figure 7.

Class conceptions about “living beings” (n = 26).

These results demonstrate that this teaching–learning process was focused on learning the concept’s elements (Shepard’s behavioural learning design, [45]); it did not focus on existing relationships. The results showed that the most of these students did not have significant learning in relation to the concept of biological similarity between living beings—tree and animal—and its link to the attitudinal learning of tree protection (ecocentric education). According to [46], meaningful learning favours the construction of answers and enables commitment and responsibility. Learning the concept of “the tree is a living being” means understanding, interpreting and having the ability to apply that knowledge to the tree as a living being. According to the theory of socio-constructivist learning [45,47], learning is conditioned by the appropriation of concepts and by the sociocultural context. It is an active process of construction and attribution of meanings. It is sensitive to motivating and challenging educational contexts. In this case, the curricular content “the tree is a living being” had already been taught. The children’s answer sheets (DS n-1) evidence the existence of previous concepts and scientific conceptions about this. The constructivist perspective about learning was confirmed. Under the point of view of [12], effective meaningful learning means that the student will have to be actively and emotionally involved in (re) building their knowledge. But it is possible to achieve if the teacher needs to know and recognizes the relevance to the students’ conceptions. The evaluation of the students’ conceptions was an effective methodological option in the (re) construction of the knowledge, as suggested by several authors [48,49].

4.1.2. Lesson—“Let’s Explore: The Tree Is a Living Being?” and “Let’s Explore: The Dog Is a Living Being?”

The DSs 2 and 3 were designed based on the analysis of the answer sheets of DS n-1 “What I already know about what are living beings”.

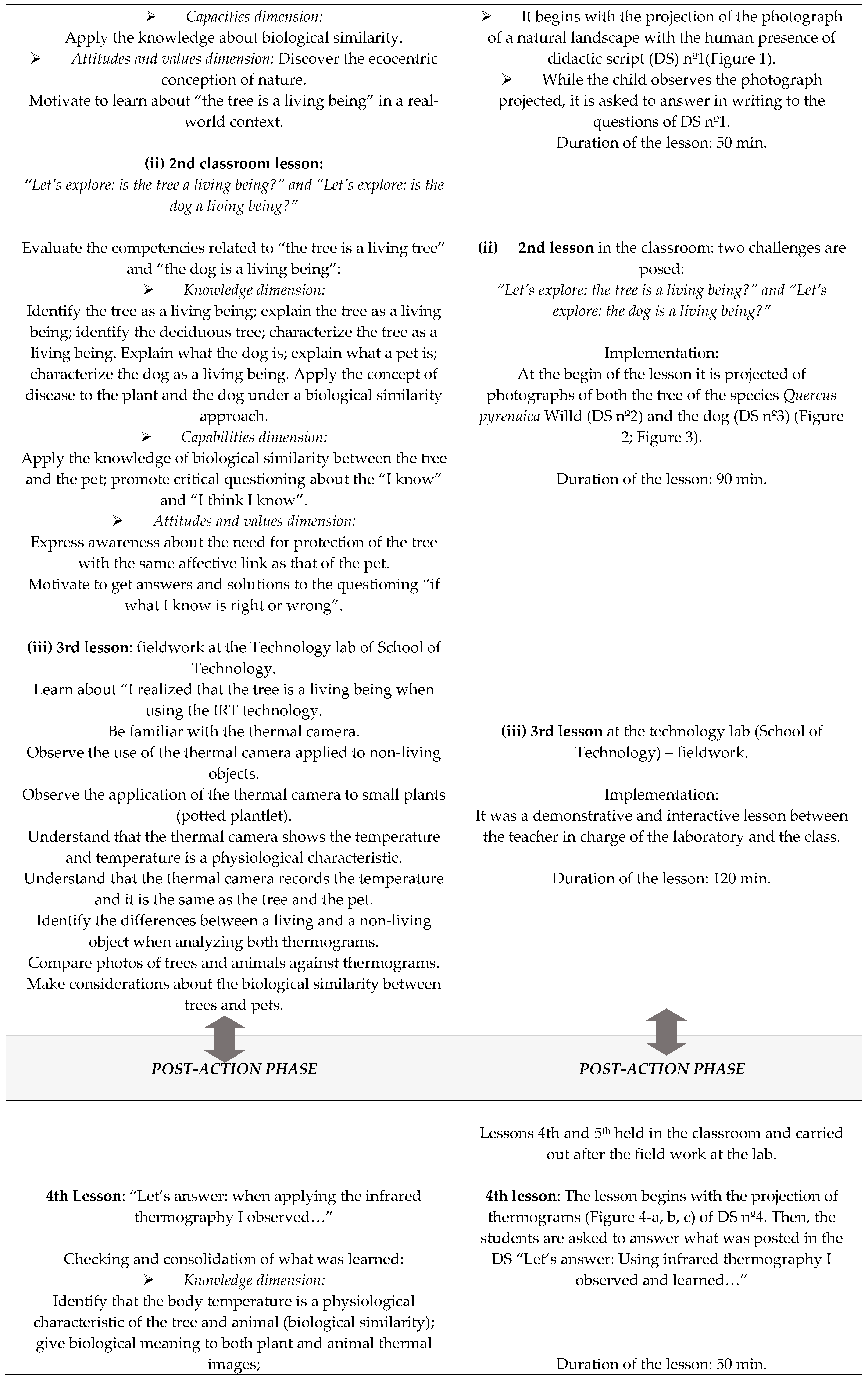

From the DS n-2 and n-3 answer sheets analysis (n = 23), Table 3, it was verified that approximately half of the group had conceptual knowledge, while only 38.4% (in relation to what is “tree is a living being “—a biological entity) explained the tree as a living being that is important and useful for people. A student wrote:” because it gives us good air to live and a few more things.” In relation to the living dog, 73% of these children explained the dog as a pet that is useful. A student wrote: “it is an animal that gives us joy when we are sad, and it plays.” Only 31.7% are critically involved in their knowledge of the “dog is a living being”. They do not know the meaning of disease (biological conception). Although they know the terminology “illness” they revealed common-sense conceptions “because everyone can get sick” as one of the students wrote. Most of these children associate “pet” with an animal that is at home and with a utilitarian function (73%). These children showed no doubt about the ecocentric conception about “living tree”, as 92.3% of them identified it as being alive.

Table 3.

Knowledge and attitudes about the “tree is a living being” (a) and “the dog is a living being” (b) and examples of transcriptions of student’s contributions.

The didactic model (interrelation between science, tree and society) applied in the construction of the DSs (1,2, and 3) of this DPI proved to be adequate for the analysis of the competences of these children. At the same time, it provided a motivational context for the discovery of “what I know is correct”—“knowledge in action”. The child was involved in the development of their learning. The child was centred on the opportunity and the need to decide the way in which this process is (re)constructed. They all wanted to go to the technology lab. This type of study provides unique opportunities for meaningful learning; simultaneously it is a significant time in the process of personal and social formation [35].

The analysis of DSs n-2 and n-3 answer sheets shown the unequivocally expressed will to learn about trees; it was a consequence of the technology laboratory experience. Children are actively involved and motivated (re) constructing their conceptions: “... because I will get to know more about the trees and check if my answers are right:” is a wished meaningful learning. The role of the teacher, and their strategies and didactic resource can stimulate the child in the search of how to find the best way to overcome their doubts and difficulties.

4.1.3. Lesson—Fieldwork at the Technology Lab

The children were always very participative and sociable. Table 4 shows what was learned when observing the group during this lesson.

Table 4.

Learning results as a consequence of the intervention of the teacher in charge of the laboratory.

The observed conceptual apprenticeships showed the efficacy of the teaching-learning process. These children performed the (re) construction of conceptions in relation to what they observed and about what they experienced. The child progressively establishes relationships between ideas until they created a basis for developing more complex and structured ideas. “There is no competence without knowledge, just as no one solves problems with knowledge alone” [50] (p. 96). The attitudes dimension is shaped by cognitive, affective and behavioural components. At the level of ecocentric education in science education, it highlights the need to awaken children at an early age for a sense of responsibility towards nature emphasizing the serious environmental problems, in which deforestation is included.

It was realized that listening, observing, giving the children time to express their opinions, and giving value to their explanations enhanced the dialogue interactivity. It makes it possible to perceive what they learned about “the tree is a living being”. It was observed the development of communicative skills and critical thinking. The social interaction and dialogue are basic elements of the development of cognitive processes [51].

Both, the technological resources and the practice were effective learning tools. It contributed to raising awareness about the urgent need to take actions to protect the “living tree”.

In fact, teaching about “the tree is a living being” in the Technology lab ambient favoured the learning of the relation science-technology-tree-society. It is concluded that it activated an ecocentric consciousness in this group of primary school children.

4.1.4. Lesson—“Let’s Answer: Using Infrared Thermography I Observed and Learned…”

From the analysis of children’s answer sheets of DS n-4 (n = 26), results of which are shown in (Table 5), it was found that the children considered effective the methodological options and didactic resources of DPI in the promotion of ecocentric education about “the tree are a living being”.

Table 5.

Knowledge and attitudes about “the tree is a living being” and the “living dog” after the lesson in the laboratory.

The technology lab created a learning context. The out-of-school activities (with the IRT) shows that it provided significant learning. It was achieved through the cognitive conflict relation of curricular concepts (content and attitudinal) (ds n-1, 2, and 3) and the participation of the researcher (Table 5). We observed that the DPI facilitated the transfer of learning; for example the discussion about the observations made in Table 5. The children showed that they had acquired ecocentric transferability skills (example: “I’m going to put on my Facebook today to not cut the trees”). The children showed pro-active behaviour in the search for a solution for tree protection. It was shown that the teacher plays a key role in enabling the student to achieve the transfer of learning [52]. A propositional attitude towards the protection of the tree was observed that led us to conclude that these children were involved in the experience. Attitudes and behaviors are correlates [53]. The dialectic methodology followed by the researcher proved to be a teaching strategy that promotes pro-activity in relation to tree protection attitudes. These children showed great enthusiasm in the experience and discussions, highlighting that the teaching strategy and the didactic resources constructed were adequate to the objectives of the intervention.

The observations and the analysis of the answer sheets allowed us to verify that these students: (re) constructed their knowledge and attitudes regarding the tree; they valued getting to know about the IRT and its application to living beings; they valued being involved in the need to protect the tree because a “Tree is a living being”.

4.1.5. Lesson—Debate on “What I Know Now about the Living Tree”

Fifteen days after the study was carried out, a lesson to discuss the theme was held. The theme was: “What I now know about the living tree.” The class was organized into three groups. The option of the debate as a teaching strategy was intended to bring the learning context closer to the context of society debates at the television. It was found to have provided an approximation in the classroom to the sociocultural contexts of the daily life of these children. In fact, it proved to be the engine of great enthusiasm in wanting to express ideas from each group. In addition, the debate showed effectiveness in developing skills such as: how to wait in turn to participate, how to listen to the opinions of each group, synthesizing the ideas that the group conveyed. The classroom became a space for oral communication and exchange of ideas.

In order to verify the learning achievements and the need to reinforce the teaching–learning process, the teacher sequentially asked questions (Table 6) related to those of the DSs. It was confirmed that the children learned. However, in DS Nº4 it was found that 30% of students still showed an anthropocentric conception (answer example “No, because both are useful for our health and life”). In view of these result, the teacher reinforced the critical reflection dialogue. The teacher requested group I to share their ideas about the thinking of groups II and III, and groups II and III were requested to better explain their ideas. At the end of the dynamic participation in the discussion, it was agreed that group I would share the views of group II and group III.

Table 6.

Synthesis of the learning observed in the debate.

When we did an overview of the development of DPI (Figure 5), it turns out that it was possible to develop a science–technology–tree–society interrelationship and promote the ecocentric education of children.

4.2. Training of the Reflective/Research Teacher (Competence in the Use of IRT)

In view of the results observed on students learning, it was found that the planning-action-observation-reflection model, applied in this research, developed competences to use IRT in ecocentric education of children. This experience brought the future primary teacher closer to a children´s ecocentric education approach.

Along the development of the pre-action phase, it was possible to observe motivation and worthiness for teamwork. The STP student emphasized the relevance of the options selection process for DPI. The student drew attention to the development of the investigative and reflexive process to choose the options for structuring and operationalizing DPI. According to the analysis of the results observed in the DS (Figure 7), the student mentioned how relevant this process is since the student concluded that “the teaching complexity involved is astonishing”.

Analysing the results of the children’ learning (Table 5) highlights that the time spent in work meetings to reflect on and investigate how to (re)build their pedagogical knowledge in order to innovate the practices applying IRT was worth it.

5. Conclusions

This research highlighted the potential of thermograms (images) as a didactic resource in the development of children’s ecocentric education. This research evidenced how the model of the pedagogical formation of future teachers could be a key factor for the development of children ecocentric education.

In this investigation, the educational process itself was placed at the centre of educational research. The results showed how action-research contributed to the development of professional competencies for the promotion of ecocentric education. It promoted the development of investigative and reflexive skills during the STP process (we could say that the development of these capacities occurred in situ, that is, the class is the “ideal laboratory” of the educational process). The STP student when assuming a reflective–investigative role was able to diagnose and analyse the class conceptions about “livings beings”, allowing her to seek and develop the methodological strategies most appropriate to the (re)construction of knowledge by the children, that is to promote ecocentric education. It was a didactic–pedagogical practice that focused on the student. It was shown to be effective in the process of developing pro-environment attitudes and interest in scientific knowledge in the construction of ecocentric education. Operationalization strategies to (re)construct knowledge for capacities acquisition and pro-active attitude strengthening were learned. It has been demonstrated the enhancement of learning when the interconnection of science education with ecocentric education is carried out.

Learning about “the tree is a living being” by applying IRT showed that thermography technology associated with dialectical methodology pedagogical revealed potentialities in the development of ecocentric education. Ecocentric conceptions were constructed by observing, experiencing, and bringing these children closer to scientific knowledge. It was observed that the IRT motivates the students for learning about the “tree is a living being” because the IRT reveals the hidden world of this living being. That is, it was possible to see the biological similarity (temperature) between animal and tree. It was possible to develop abstract elaboration (motivated by thermal imaging), debate and proactivity in relation to the tree’s socio-environmental context. Learning from the application of a technology (in this case it was IRT) has meant to integrate the child in the current techno-scientific society, and to create opportunities linked to real contexts for discussion and resolution of a sensitive condition (preserving/protecting the tree) which we believe is a contribution to sustainability.

6. Limitations

It should be noted that any teaching strategy is always only a means by which meaningful learning is favored. It is considered a limitation of this study the generalization because it is applied although it was a one-off intervention. It is not possible to generalize about the didactic-pedagogical intervention developed.

There were no time constraints for lessons implementation. There was no limitation in the construction/adaptation/reflection of didactic resources and dialectic methodology. In addition, these students were assiduous. Class size is small. This was an advantage because the teaching–learning process in the class was carried out more easily.

7. Recommendations

The teaching of to preserve the tree constitutes the pedagogical objective of Natural Sciences subject at any level of education. However, current society continues to face serious environmental problems, in which the destruction of forests and the lack of caring for the tree as a living being is the main issue. It is concluded that the current education of future teachers needs adjustments to respond to the challenges of society.

Currently, there is a need to look for new teaching paths. It is necessary to respond to current societal-environmental requirements. Researchers in education at Higher Education Institutions need to pay particular attention to the educational process of the science curriculum content.

Both societal demands and serious environmental problems require the (re)construction of strategies and didactic resources for the promotion of ecocentric education of children and young people. We need to educate children who are able to collaborate in finding answers and solutions to serious environmental problems. However, the promotion of this education requires teachers who are sensitized and motivated to develop it.

Although this study was carried out in primary education, it would be very interesting to understand the effectiveness of the IRT applied to trees actually contributing to the development of the ecocentric education of students at other levels of education on the training of future teachers. It is also suggested that this is carried out with university students studying natural science subjects.

Author Contributions

M.E.F. and R.P. designed the study, developed the methodology, performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. M.E.F. supervised A.C.A. to carried out the implementation of the study at the supervised teaching practice.

Funding

This study is framed in the activities of the project “TreeM—Advanced Monitoring & Maintenance of Trees” Nº.023831, 02/SAICT/2016, co-funded by CENTRO 2020 and FCT within PORTUGAL 2020 and UE-FEDER structural funds.

Acknowledgments

The authors are gratefully acknowledged the Ana Margarida Cardoso the involvement of the class of students in this study. We would also like to thank João Crisóstomo for the technical support with the photos and thermograms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Calleja, J.M.R. Os professores deste século. Algumas reflexões. Revista Institucional Universidad Tecnológica del Chocó 2008, 27, 109–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.E.R.; Dias, H. Uma experiência na formação de futuros professores primários: Aprender sobre ambiente através do ensino das ciências. Revista Electrónica De Investigación En Educación En Ciencias 2018, 2, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Loughran, J.J. Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2002, 53, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcão, I. Professores Reflexivos em Uma Escola Reflexiva; Cortez: São Paulo, Brasil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leitch, R.; Day, C. Action research and reflective practice: Towards a holistic view. Educ. Action Res. 2000, 8, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal-Lei de Bases do Sistema Educativo—[LBSE]. Lei nº 46, de 14 de Outubro 1986; nº 237, I Série, A; Diário da República Portuguesa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Portugal-Ministério da Educação [ME]. Organização Curricular e Programas: Ensino Básico—1º Ciclo, 4th ed.; ME-DEB: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.E.; Porteiro, A.C.; Pitarma, R. Enhancing Children’s Success in Science Learning: An Experience of Science Teaching in Teacher Primary School Training. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, I.; Veiga, M.; Teixeira, F.; Tenreiro-Vieira, C.; Vieira, R.; Rodrigues, A.; Couceiro, F. Educação em Ciências e Ensino Experimental—Formação de Professores; Ministério da Educação: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007.

- Sá, J. Renovar as Práticas no 1º Ciclo Pela via das Ciências da Natureza, 2nd ed.; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E. The new environmental paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Pérez, D.; Guisásola, J.; Moreno, A.; Cachapuz, A.; Pessoa de Carvalho, A.M.; Martínez Torregrosa, J.; Salinas, J.; Valdés, P.; González, E.; Gené Duch, A.; et al. Defending Constructivism in Science Education. Sci. Educ. 2002, 11, 557–571. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, J. A Natureza de uma disciplina de didática: O caso específico da Didáctica das Ciências. Revista de Educação 2002, XI, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Femdman, A.; Altrichter, H.; Posch, P.; Somekh, B. Teachers Investigate Their Work. An Introduction to Action Research Across the Profissions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Formosinho, J.; Niza, S. Iniciação à Prática Profissional: A Prática Pedagógica na Formação Inicial de Professores. Projecto de Recomendação; INAFOP: Lisboa, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, A. La Investigación-Acción. Conocer y Cambiar la Práctica Educativa; Editorial Graó: Barcelona, Espanha, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Committee on Culture and Education of the European Parliament European Parliament, A6-0304/2008. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+REPORT+A6-2008-0304+0+DOC+XML+V0//PT (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- Holst, G.C. Common Sense Approach to Thermal Imaging; SPIE—The International Society for Optical Engineering Bellingham: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Assmann, H. Reencantar a Educação: Rumo à Sociedade Aprendente; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brasil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gadotti, M. Perspectivas Atuais da Educação; Artes Médicas: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, J. Renovar as Práticas no 1º Ciclo Pela via das Ciências da Natureza; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, C. Os Professores e a Concepção Construtivista; Edições ASA: Porto, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, D. Teaching and Learning Science: Towards a Personalized Approach; Open University Press: Buckingham, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Savery, J.R.; Duffy, T.M. Problem-based learning: An instructional model and its constructivist framework. In Constructivist Learning Environments: Case Studies in Instructional Design; Wilson, B., Ed.; Educational Technology Publications: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, D.P. Psicología Educativa: Un Punto de Vista Cognoscitivo; Editorial Trillas: Mexico City, México, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, F.; Coelho da Silva, J.L. Investigação Educacional e Transformação da Pedagogia Escolar. In Actas do Congresso Ibérico/5º Encontro do GT-PA em Pedagogia Para a Autonomia; Universidade do Minho-CIEd: Braga, Portugal, 2011; pp. 547–557. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, F.S.; Gonçalves, A.B. Educação ambiental e cidadania: Os desafios da escola de hoje. In Actas dos Ateliers do Vº Congresso Português de Sociologia Sociedades Contemporâneas: Reflexividade e Acção Atelier: Ambiente; APS Publicações: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente-Portugal. Estratégia Nacional de Educação Ambiental 2020; Ministério do Ambiente: Lisboa, Portugal. Available online: https://www.apambiente.pt/_zdata/DESTAQUES/2017/ENEA/AF_Relatorio_ENEA2020.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Uzzell, D.; Fontes, F.; Jensen, B.; Vognsen, C.; Uhrenholdt, G.; Gottrsdiener, H.; Davallon, J.; Kofoed, J. As Crianças Como Agentes de Mudança Ambiental; Campo das Letras: Porto, Portugal, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez-Alonso, A.V.; Manassero-Mas, M.A. Una evaluación de las actitudes relacionadas con la ciencia. Enseñanza de las Ciencias 1997, 15, 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Zacharia, Z.; Barton, A.C. Urban middle-school students’ attitudes toward a defined science. Sci. Educ. 2004, 88, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J.; Inhelder, B. A Psicologia da Criança; Edições ASA: Porto, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pitarma, R.; Crisóstomo, J.; Jorge, L. Analysis of Materials Emissivity Based on Image Software. In Proceedings of the WorldCIST’16 Conference—4th World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, Recife, Brazil, 22–24 March 2016; pp. 749–757. [Google Scholar]

- Pitarma, R.; Crisóstomo, J.; Ferreira, M.E. Learning About Trees in Primary Education: Potentiality of IRT Technology in Science Teaching. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN18 Conference, Palma de Maiorca, Espanha, 1–3 July 2018; pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- OECD-Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Available online: https://www.pisa.tum.de/en/domains/scientific-literacy/ (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- Roldão, M.C. Gestão do Currículo e Avaliação de Competências: As Questões dos Professores; Editorial Presença: Lisboa, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Perrenoud, P. Porquê Construir Competências a Partir da Escola? Desenvolvimento da Autonomia e Luta Contra as Desigualdades; ASA Editores: Porto, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, D.; Carrascosa, J.; Furió, C.; Martínez, J. La Ensenanza de Las Ciencias en la Educación Secundaria; Horsori: Barcelona, Espanha, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, C.P.; Sousa, A.; Dias, A.; Bessa, F.; Ferreira, M.J.; Vieira, S. Investigação-acção: Metodologia preferencial nas práticas educativas. Revista Psicologia Educação e Cultura 2009, 2, 355–379. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita-Pires, C. A Investigação-acção como suporte ao desenvolvimento profissional docente. Revista de Educação 2010, 2, 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.; Biklen, S. Investigação Qualitativa em Educação: Uma Introdução à Teoria e aos Métodos; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, A.B. Investigação em Educação; Livros Horizonte: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gipps, C.; Stobart, G. Alternative Assessment. In International Handbook of Educational Evaluation; Kellaghan, T., Stufflebeam, D.L., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 549–576. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, L. The role of classroom assessment in teaching and learning. In Handbook of Research on Teaching; Richardson, V., Ed.; American Educational Research Association: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J.D. Aprender, Criar e Utilizar o Conhecimento: Mapas Conceituais Como Ferramentas de Facilitação nas Escolas e Empresas; Plátano Edições Técnicas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, L. The role of classroom assessment in learning culture. Educ. Res. 2000, 29, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlen, W. The Teaching of Science in Primary Schools; David Fulton Publishers: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, R.; Squires, A.; Rushworth, P.; Wood-Robinson, V. Making Sense of Secondary Science: Research into Children’s Ideas; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.I. (Coord) Despertara Para a Ciência: Actividades dos 3 aos 6; Ministério da Educação—Direcção-Geral de Inovação e de Desenvolvimento Curricular: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. A Formação Social da Mente; Martins Fontes: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, G.L.; Bahia, S. Psicologia da Educação: Temas de Desenvolvimento, Aprendizagem e Ensino; Relogio D’Agua: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shrigley, R. Attitudes and behavior are correlates. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1990, 27, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).