3.1. The Importance of Anti-Money Laundering for Sustainability

The concept of sustainability proposed by researchers (e.g., Holmberg, Reed, and Harris) consists of three essential aspects of development: economic, environmental, and social. One can generalize that an economically sustainable system exists, when constant production of goods and services goes with maintaining manageable levels of government and external debt. This also means that there is the need to avoid extreme sectoral imbalances that damage agricultural or industrial production. An environmentally sustainable system requires establishing a stable resource base. Depleting non-renewable resources is realized to the extent that investment is made in adequate substitutes. This means a multidimensional approach to using the environment. For example, the maintenance of biodiversity, atmospheric stability, and other ecosystem functions. A socially sustainable system means fairness in distribution and opportunity. This includes, but is not limited to, an adequate provision of social services, including health and education, gender equity, and political accountability and participation [

21]. The concept of sustainability is multi-layered and could be adopted for complex social and economic phenomena, such as power structure, quality of education, and social innovations [

22,

23,

24]. Moreover, it seems important to apply sustainability as the approach to resolve different, detailed, social, and economic problems [

25]. Urban poverty or stakeholder engagement and responsibility [

26,

27], but also the anti-money laundering model [

8] could serve as examples of this. To implement such an approach, there is a necessity to establish an international platform for the sustainable model supported on an institutional level. United States Nations Development Goals have a chance to fulfil these criteria. In the process of achieving sustainability by macro-structures, meta-governance plays an important role. The term “meta-governance” is understood as the process of steering devolved governance processes or more simply as the “governance of governance” [

28].

Harris aptly notes that economic sustainability requires that the different kinds of capital making economic production possible must be maintained and developed. This means that manufactured and natural capitals must be complemented by human and social capitals. It is essential that all four of these capitals are maintained in the long term. From an ecological perspective, both human population and total resource demand must be limited in scale [

21]. This postulate; however, is difficult to fulfil. It is very difficult to limit resource consumption in the conditions of economic development in China, India, or Brazil where the total population is over 2 billion people. Reducing the cost of producing and using alternative energy sources will reduce the demand for non-renewable resources. The achievement of this goal is real, but the problem of meeting the food needs of the rapidly growing world population remains unsolved. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015, are the most relevant and recent attempt to obtain global agreement on 17 of the most important issues that involve all countries and their economies and societies. Climate protection, reduction of poverty and social exclusion, development of education, more equitable distribution of GDP, protection of natural resources for future generations, innovations, and implementation of the idea of governance in public life are goals that would benefit all inhabitants of our planet [

29].

The implementation of these goals requires the allocation of significant financial resources for different purposes. In many cases, the implementation of the objectives could involve excessive expenditure and may lead to a public deficit or even a national debt. The increase in the tax burden can lead to domestic economies becoming a less attractive investment opportunity. Unbalanced public finances make it difficult to implement the concept of an innovation in the state and its economy, which seems to be necessary in the efficient realization of SDGs. The analysis of potential threats to the implementation of SDGs emphasizes the need for seeking solutions that allow the government to increase its income without the need to raise taxes or limit social privileges. It is also worth highlighting that expenditure reduction does not help to implement innovative solutions in SDGs. Although budget balance can be achieved, the cost of such a policy is enormous. This can involve a loss of a competitive position in the global chain of cooperation based on innovations. Governments can maintain their position in the chain of cooperation and competition through eliminating the scale of financial crime, hence eliminating situations in which financial resources, instead of supporting the public budget and realization of SDGs, go to the accounts of criminals using money laundering.

Money laundering is “the processing of these criminal proceeds to disguise their illegal origin. This process is of critical importance, as it enables the criminal to enjoy these profits without jeopardizing their source” [

30], or “the method by which criminals disguise the illegal origins of their wealth and protect their asset bases, so as to avoid the suspicion of law enforcement agencies and prevent leaving a trail of incriminating evidence” [

31], or the process through which criminals give an apparently legitimate origin to proceeds of illegal activities [

8]. The review of the literature [

1,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44] shows that the definitions of money laundering proposed by various authors do not differ from those proposed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and the Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures and the Financing of Terrorism, as presented above in this article (

Table 1).

Whichever definition of money laundering is used, this process can be understood from its purpose. Money laundering aims to reduce or eliminate the risk of seizure or forfeiture of illegal funds obtained by criminals.

The threat of money laundering is underlined by De Koker and Turkington [

45], and by Panibratov and Michailova [

46]. Money laundering is one of the essential types of organizational pathologies that can be perceived through the prism of its impacts on the state, banking system, individual business, and individuals. Money laundering is dangerous for the stability of states and their economies for several reasons. First, it can disrupt a country’s banking system that relies heavily on trust. Second, it can have a negative impact on a country’s monetary policy, including budgetary balance. Third, it can negatively influence the predictability of a country’s financial markets by eroding public trust. From the perspective of the proponents of the new institutional economics, a generalization can be formulated that money laundering disturbs the institutional order. Money laundering catalyses other organizational pathologies and influences on the corporate image and public trust [

1,

10,

11,

47]. It can also be the result of the existence of other pathologies. Therefore, money laundering should not be analyzed in isolation from corruption, fraud or the shadow economy [

1].

There are two reasons why criminals—either drug traffickers, corporate embezzlers or corrupt public officials—need to launder money. The money obtained during illegal activities constitutes an evidence of their crime, and the money itself is vulnerable to seizure and has to be protected [

31]. Actions to strengthen the anti-money laundering system should, therefore, constantly increase the risk of money laundering being revealed by public organizations. The increase in the cost of money laundering will make this practice less profitable for those gaining profits from organized crime [

1].

The money laundering, which aims to give the real value of items derived from the illegal activities, is carried out using techniques such as “structuring”, “smurfing”, or “blending”. Splitting large amounts of financial transactions into smaller amounts is intended to avoid detection of money laundering. This procedure (“structuring”) can be implemented through multiple entities (“smurfing”), which additionally makes it difficult to identify money laundering. “Structuring” and “smurfing” can be used in the placement, which is the first stage of the process of money laundering and intends to place illegal funds into the financial system. The second money laundering stage, entitled layering, occurs after the illegal funds have entered the financial system. The aim of this stage is to separate illegal gains from their criminal source. Funds can be transferred by check, money order, or bearer bond, or transferred electronically to other accounts in various banks. The third stage, entitled integration, involves the integration of funds into the legitimate economy. This is realized through the purchase of assets, such as real estate or other luxury goods or by “blending”, which means providing illegal funds to legal business by mixing such funds with legal incomes. In this stage accounting fraud is necessary.

3.2. Key Stakeholders of Anti-Money Laundering

The FATF is an inter-governmental organization established in 1989 by the ministers of its member jurisdictions. The FATF aims to set standards and “promote effective implementation of legal, regulatory and operational measures for combating money laundering, terrorist financing and other related threats to the integrity of the international financial system” [

48]. The FATF comprises of 35-member jurisdictions and 2 regional organizations, representing the most major financial centers in all parts of the world [

49]. FATF observer organizations include, among others, the African Development Bank, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Central Bank, Eurojust, Europol, Inter-American Development Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), Interpol, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), United Nations—United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), United Nations Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate (UNCTED), and the World Bank. FATF associate members include, among others, the Council of Europe Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures and the Financing of Terrorism (MONEYVAL) [

49].

Typically, as presented in

Figure 1, national anti-money laundering systems consist of four main stakeholders. They include financial intelligence units (FIU), cooperating units (CU), obligated institutions (OI), and law enforcement agencies (LEA). Domestic FIUs often cooperate with FIU from other countries (foreign FIU–FFIU).

Under existing national laws, FIUs may be a part of a ministry of finance, a law enforcement institution or a central bank. They play a key role in national anti-money laundering systems. According to FATF standards, FIU is usually involved in the process of acquiring, collecting, processing, and analyzing information in the manner prescribed by law [

1,

50].

Domestic FIU (

Table 2) undertake actions aimed at counteracting money laundering and terrorist financing, particularly by [

1,

50].

Depending on the legal requirements, a FIU may be obliged to submit an annual report on its activities to the prime minister, president, or parliament within a period of time after the end of the year [

1,

50].

Obligated institutions include branches of a credit institution, any financial institutions, banks, electronic money institutions, payment institutions, investment companies, custodian banks, legal entities carrying out brokerage activities and commodity brokerage houses, entities operating in the field of gambling, insurance companies, investment funds, investment fund management companies, notaries in so far as operations concern trading in asset values, attorneys, legal advisers practicing their profession outside their employment relationship with agencies providing services to the government authorities and local government units, active tax advisers, entities operating in accounts bookkeeping services, entities carrying out activities in currency exchange, entrepreneurs engaged in auction houses, antique shops, business factoring, trading in metals or precious/semi-precious stones, commission sale or real estate brokerage, foundations, associations, entrepreneurs receiving payment for commodities in cash to a value equal to or exceeding some established by law quota of money, or when the payment for a given product is made by more than one operation [

1]. Banks play a key role in the modern financial system. However, the researchers underline the problem that shareholders are willing to take on high-risk projects that maximize their values at the expense of the deposits and that such activities have an influence on bank liquidity [

51]. Banks are usually proper obligated institutions, but the case of some Nordic banks showed that they may participate in money laundering knowingly, because of the incentives of bank managers [

52]. Therefore, the role of compliance systems in the prevention of practices that harm sound economic relations is pointed out in the literature [

53].

Obligated institutions have several duties related to counteracting money laundering (

Table 3).

Taking into accounts duties of obligated institutions, there is no doubt that in such a model of the anti-money laundering system, the obligated institutions play a key role and their reliability, as well as the effectiveness of the monitoring of anti-money laundering system performed by the FIU, determine whether money laundering takes place. The effectiveness mentioned above also depends on the system solutions in the field of counteracting the shadow economy. For example, an antiquarian shop can register every tenth transaction made. Therefore, in this respect, FIU will have the required information about clients of every tenth transaction. On the other hand, FIU will not have information regarding other transactions not reported for taxation. There is, therefore, a close relationship between money laundering and a shadow economy [

1].

In accordance with FATF standards and national law, any obligated institution conducting a transaction exceeding some amounts (for example 15,000 euros in the case of Poland) is required to register such a transaction. The procedure also applies if it is carried out by more than one single operation but the circumstances indicate that they are linked and that they were divided into operations of lower value with the intent to avoid the registration requirement (“structuring”). The ability to link the client’s transactions characterized by lower values and the ability to demonstrate that it was the client’s attempt to circumvent the anti-money laundering system requires obliged institutions, not only to have an appropriate IT system, but also staff with the required knowledge and skills. Regardless of registering the transactions mentioned above, any obligated institution conducting a transaction, the circumstances of which may suggest that it was related to money laundering or terrorist financing, is required to register such a transaction, independently of its value and character [

1].

Detection of suspicious transactions by obligated institutions requires employees of these institutions to have specialist knowledge and skills. Certain requirements regarding the identification of suspicious transactions should be established. For example, making transactions from certain countries may be suspicious. Customer behavior should also be taken into account. This makes one realize that in such cases, the role of FIU will consist in examining and assessing the criteria for specifying suspicious transactions used by obligated institutions, evaluation of compliance by obligated institutions with their requirements, and evaluation of the effectiveness of training of their employees. FIU can also support the process of training employees of obligated institutions by offering specialized courses. FIU’s cooperation with obligated institutions in training their employees is underlined in literature as a way to improve anti-money laundering (AML) prevention [

54]. As mentioned above, an obligated institution has to carry out an ongoing analysis of the transactions carried out. The results of those analyses need to be documented in paper or electronic form to be kept for a period established by domestic law. An obligated institution that identifies a suspicious transaction is obliged to inform FIU about this fact in writing by passing all the data related to such suspicious transactions and is obliged to cooperate with FIU in a manner prescribed by law. For example, an obligated institution cannot carry out the transaction when the account is blockaded [

1].

In addition to FIUs and obligated institutions, other competent institutions play an important role in anti-money laundering systems. Their role and composition depend on legal solutions adopted in a particular country. Other competent institutions can include prosecution offices, internal security agencies, tax authorities, customs authorities, and even SAIs. Within their statutory authority, such cooperating units (

Table 4) are obliged to cooperate with FIU in efforts to prevent money laundering and/or terrorism financing [

1,

50].

FIUs cooperates with law enforcement agencies by notifying them of offences of money laundering (

Figure 2). Domestic FIUs cooperate with foreign FIUs based on bilateral agreements (

Figure 3). FIUs exchange information necessary to identify suspected financial transactions, individuals, and entities [

1,

50].

In addition, FIUs cooperate in training activities. For example, the Egmont Group organized in Poland, on 23–25 April 2019, a workshop called “Group Corporate Vehicles and Financial Products” for representatives of FIUs. Initially, the Egmont Group was established in 1995 in Brussels as an organization gathering FIUs from European Union countries and the USA. In 2007, a decision was made to transform this group, gathering financial intelligence units from 105 countries into a formal international organization [

55,

56,

57].

FIUs coordinate their other tasks. For example, the task of the Expert Group on Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (EGMLTF) is to support the European Commission in setting policy directions in the field of counteracting money laundering and terrorist financing, preparing legal acts, as well as advising at the stage of preparing proposals for implementing measures and coordinating cooperation between EU Member States. At EGMLTF meetings, FIUs update information on the progress in the preparation of national money laundering and terrorist financing risk assessments. EGMLTF collects statistics from countries about the effectiveness of their systems to combat money laundering or terrorist financing. They also establish the risk-laundering and terrorist financing risk assessment at an EU level. As part of EGMLTF, a team was formed in 2018, consisting of FIU representatives from Denmark, Estonia, Liechtenstein, Latvia, Germany, and Italy, who participated in the work of the Expert Group of the Commission for Electronic Identification and Know-Your-Customer Processes. The effects of the group’s work were presented at the FATF meeting in the context of a possible modification of the Interpretative Note to Recommendation 10 FATF Customer Due Diligence in connection with non-face-to-face transactions that generate higher risk. FIUs participate in the work of the EU-FIU Platform, which is the European Commission advisory body for ongoing cooperation between the FIUs of EU member states. During the meetings of the EU-FIU Platform, the new EU initiatives in the field of counteracting money laundering and terrorist financing are discussed, as well as, proposals to improve the exchange of information between financial intelligence units, issues of joint analysis of cases with a cross-border element, the topic of transnational risk assessment, and reporting of suspicious cross-border transactions. In 2018, an important topic of the meetings of the EU-FIU Platform was the EU draft directive on the exchange of financial information and other information to combat certain offenses [

55].

As part of the EU-FIU Platform, the FIU.NET (a computer network enabling the cooperation between the FIUs in the European Union) Advisory Group was established, which supports Europol in creating development strategies for the FIU.NET network, helps in implementing innovations and provides opinions on FIU applications outside the EU for connecting to the abovementioned network. This group consists of representatives of the financial intelligence units of Austria, Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania, and Sweden, as well as Europol. In 2019, FIU representatives from Finland and Portugal joined the group [

55].

The Role of Supreme Audit Institutions in Anti-Money Laundering

In contemporary western and developed countries, the role of SAIs for governments and societies is critical because SAIs are important pillars of democracies that assist parliaments and legislatures in the exercise of their rights, concerning actions carried out by executive branches. Although governments have a key responsibility to create a system that does not favor or enables occurrence of irregularities, SAIs have a key role to play as an advocate of good governance [

1]. The important role SAIs play in promoting good governance typically results from their special position with the government. SAIs are nonpartisan organizations whose auditors provide crucial information to their countries and fellow citizens. These organizations are subordinate only to their parliaments and they are independent of their governments’ executives and judiciary branches. Having broad audit authorities, SAIs evaluate the functioning of a whole government system. From such a broad perspective they can advise one on how to strengthen public institutions. SAIs carry out the state budget, the realization of tasks required by legislation, and other actions taken by the executive. In addition, the work of SAIs is a tangible manifestation of a concern for the proper functioning of the state administration, proper implementation of public services, and the interest of citizens. Through these activities, SAIs help to reinforce the legitimacy of the public government as well as enhance the democratization, thriftiness, and effectiveness of the public sector through the implementation of the financial management principles adopted in the private sector, and through activation of social control [

1]. Given the role of SAIs in modern countries, a generalization can be formulated that SAIs participate in “meta-governance”. The term “meta-governance” is understood as the process of steering devolved governance processes or more simply as the “governance of governance” [

28]. The theoretical reasoning, with the earlier research, showed the necessity of SAI involvement in combating corruption and other types of organizational pathologies [

1]. Considering the scale of money laundering in the world is the result of relatively low-level of protection against money laundering, the research objective is justified.

3.3. Auditing the Anti-Money Laundering System—Auditors’ Dilemmas and Constraints

The problem which arises in the case of auditing anti-money laundering systems is the consequence of domestic laws and regulations that provide the basis of the legal authority of the FIU and define the scope of its cooperation with other AMLOs [

1]. One can generalize that the position of FIU in the macrostructure—the state—determines the possibility of auditing such organizations. For example, in some countries (Poland), FIU was created within the Ministry of Finance, which enables SAI auditors to gather the necessary evidence and carry out reviews and evaluation of FIU’s activities [

55,

58,

59]. In other countries, FIUs may be part of the central bank or law enforcement authorities. Banking secrecy can hamper efforts to obtain information about a FIU’s activities. In addition, information related to criminal investigations is typically unavailable to auditors. For example, to develop information on the vulnerabilities to money laundering in the credit card industry GAO asked officials from different government agencies for information about any cases they were aware of pertaining to credit cards and money laundering. GAO faced problems in obtaining requested information and documentation because of confidentiality and privacy issues [

60]. In the case of the Polish SAI, an audit of the FIU is possible, as the FIU is the part of the Ministry of Finance. SAI revealed; however, that some groups of obligated institutions were generally not audited by the FIU [

58]. Due to the scale of FIU operations (the number of obligated institutions), the SAI had to limit the scope of its audit [

59].

Another problem is the fact that while it is easy to focus the auditor’s attention on monitoring the implementation of international regulations in the domestic legal system, this does not mean that the anti-money laundering system created by the law will efficiently combat money laundering. For example, organizations using a “blending” approach (mixing legal and illegal business activity) usually fulfil their tax obligations properly. Sometimes the lines between tax management and tax evasion are blurred [

61]. This means that the internal revenue service should analyze very good taxpayers through the prism of whether sales and income declared by the taxpayer were documented or if the transactions were fictitious. Reliable accounting systems as well as replacing cash transactions using non-cash transactions will increase the effectiveness of combating money laundering. Taking into account these issues, one can formulate a generalization that the anti-money laundering process should be viewed from a broader perspective than only the activities of the FIU, obligated institutions, and cooperating units, although they are crucial for the AML system. One needs to analyze both the process of combating money laundering and activities restricting the scale of the shadow economy and corruption [

1]. Both GAO and Polish SAI did not analyze issues during their audits to the extent described above [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62].

During interviews, the SAI’s representatives who participated in activities of INTOSAI WGFACML underlined (all of them) that there is a lack of a comprehensive audit approach to AMLOs’ activities that enables an evaluation of the effectiveness of an AML system. SAIs carry out audits of single organizations from an AML system or try to carry out such an audit on a bigger scale, evaluating some parts of the cooperation between AMLOs. Such audits are usually focused on legal issues and rarely enable the evaluation of the effectiveness of AMLOs, considering the effects of their cooperation with other organizations. There is a lack of an audit of the whole AML system, especially evaluations of the achievement of established objectives, measures employed, and effectiveness of initiatives taken by all AMLOs that are part of the AML system.

All SAI auditors who participated in interviews confirmed that the provision of audit services related to anti-money laundering enhances auditors’ credibility. They formulated the opinion that the auditors’ credibility increases through the improvement of effectiveness of the anti-money laundering system. However, the SAI auditors (except the Polish ones) confirmed that they do not have sufficient knowledge and experience in conducting the audit of entities creating an anti-money laundering system. The auditors (all of them) confirmed that trust in a SAI will increase if the provision of audit services by the SAI’s auditors is to require an adherence to some established INTOSAI standards. However, such worldwide INTOSAI standards do not currently exist.

3.4. The Concept of Multiple Anti-Money Laundering Activity (MAMA) as a Universal Framework of Anti-Money Laundering and an Assessment Tool for Auditors

The effective combating of money laundering requires not only the creation of appropriate organizations, which build the anti-money laundering system, but resources that can guide, direct, and support activities in this system to move towards innovative approaches. Introducing new innovative methods of combating money laundering increases the cost of money laundering for criminals. Thus, increasing costs makes this illegal process less and less profitable. Searching for new solutions in the field of combating money laundering, it is worth using, after previous modification, the European approach to achieving excellence through Total Quality Management. Such an approach has been developed and tested in 17 public organizations in 7 EU member states. Early in the first decade of the 21st century, the Common Assessment Framework became reality, providing its users with a framework for assessing and improving their performance for achieving better quality in government operations. This model was based on nine criteria. Five criteria, called enablers, address what an organization does, whereas four results criteria address what an organization achieves [

63,

64].

The European approach to achieving excellence through Total Quality Management is a kind of business excellence model. Business excellence models can be defined as frameworks that when applied within an organization, can help to realize tasks in a more systematic and structured way that should lead to increased performance. The models are holistic, in that they focus upon all areas and dimensions of an organization and factors of performance. “These models are internationally recognized as both providing a framework to assist the adoption of business excellence principles, and an effective way of measuring how thoroughly this adoption has been incorporated. Several business excellence models exist worldwide. While variations exist, these models are all remarkably similar. The most common include: Baldrige (MBNQA)—Used in over 25 countries including US and UN; European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM)—Used throughout Europe; Singapore Quality Award Model—Singapore; Japan Quality Award Model—Japan; Canadian Business Excellence Model—Canada; Australian Business Excellence Framework (ABEF)—Australia” [

63,

64]. The proposed Anti-Money Laundering Business Excellence Model is based on the European Foundation for Quality Management with the usage of an assumption of a balanced scorecard. To combat money laundering, the use of the concept of continuous improvement for business excellence along with the tool—Common Assessment Framework, established in 2000 by the EU, enables structured organizational self-assessment of all activities and comparison of the results, carried out by those organizations—AMLOs, who are the members of an anti-money laundering system. Such self-assessment should be treated by AMLOs, as in the case of other public organizations, as a diagnostic approach for improvement of their activity [

63,

64]. One can generalize that the MAMA model should be treated as an aid to organizations for reviewing and evaluating their anti-money laundering practices, regardless of the type of organizations and the countries they come from. It is reasonable to state that the MAMA model has therefore three main purposes. First, the model should serve as an assessment tool for public organizations that want to improve their anti-money laundering activities. Second, its purpose is to act as an initial assessment tool during the risk analysis carried out by FIUs by implementing some measure of comparability between plans, processes, and the results of activities of obligated institutions. Thirdly, the model acts as an assessment tool during the risk analysis for external auditors. Finally, it allows for comparison studies between different organizations and anti-money laundering systems. Such a comparison enables and facilitates benchmarking, learning, and introducing new practices in the systems.

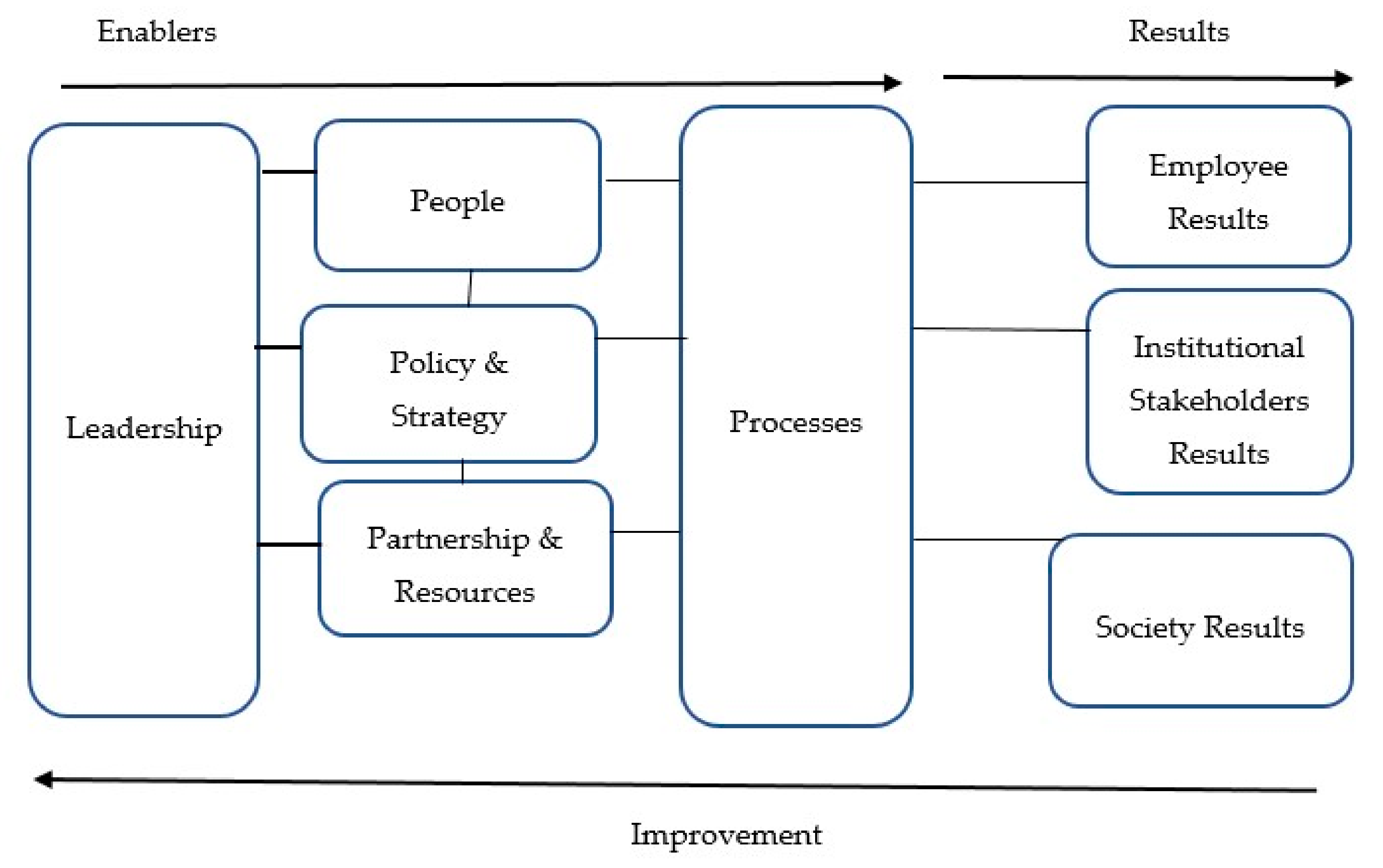

The MAMA model, which is based on the concept of the European Foundation for Quality Management Model, consists of eight criteria. Five of these are “enablers” and three are “results”. The “enabler” criteria cover what the AMLO does. The “results” criteria cover what the AMLO achieves. The MAMA model is based on the premise that results of activities with respect to institutional stakeholder results, AMLO’s employee results are achieved through leadership, policy and strategy, human resource management, partnership, resources, and processes.

Figure 4 presents the MAMA model.

The MAMA model is presented above in a diagrammatic form. The arrows emphasizes the dynamic nature of the model. They show that innovative solutions and learning help to improve “enablers” that in turn lead to improved “results” [

64]. The first criterion regards leadership. Without a clear mission and vision, it is not possible to precisely define individual goals, tasks, measures, resources, and responsible persons for anti-money laundering. Leadership enables the creation of organizational involvement with customers, or more broadly, with stakeholders. The second criterion concerns policy and strategy, which should undoubtedly be based on transparent and understandable assumptions. It is also necessary to include in this criterion, both present and future needs of stakeholders. The implementation of policy and strategy should be realized through the process of cascading, aligning, prioritizing, agreeing, and communicating plans, objectives, and targets. Human resource management is the third criterion. The process of hiring, career development, and employee’s management should consider the necessity of continuously improving the ability to identify suspicious transactions based on the analysis of the behavior of the customers of the obligated institutions. One can formulate a generalization that human resource management should be aligned with the policy and strategy, organizational structure, and anti-money laundering processes applied in the organization. Such an analysis is necessary to develop skills and new competencies of AMLO employees. The fourth criterion concerns partnership and resources. External relations may be the result of accidental actions or can be the consequence of planned undertakings. The latter situation is more beneficial from the point of view of achieving the objectives of the anti-money laundering system. Therefore, one can formulate a generalization that external partnership should be managed. This means that the scope of cooperation within the anti-money laundering system requires not only the legal framework but also planning, executing planned goals and tasks, as well as motivating employees to effective collaboration with other organizations that belong to the anti-money laundering system. It also requires the construction of an effective system for collecting and processing transaction information. The fifth criterion concerns process and change management. Data collection and processing is a process in which different constraints may occur. It is necessary that such constraints should be foreseen and appropriate remedies should be planned. The organization operates in a turbulent environment. Changes are, therefore, unavoidable. One should plan how the organization will deal with these changes. How will money laundering techniques change? How will the legal and technical environment influence the efficient anti-money laundering? The actions of the organizations that are a part of the anti-money laundering system must produce specific and visible results. The organization, in accordance with the sixth criterion, must be focused on institutional stakeholders’ satisfaction. Simultaneously, following the seventh criterion, results should be achieved in accordance with the employee’s needs and in relation to their competency development. The eighth criterion concerns the impact on society. Money laundering should be efficiently reduced, but activities taken by SAIs should also result in further preservation and sustainability of resources and creating public trust.

The MAMA model provides self-assessment that organizations need to carry out systematically, identifying their strengths and weaknesses, and forming assumptions, objectives and measurable goals for improvement plans. Such self-assessment requires an appropriate organizational culture, which is based on reliability, integrity, and accountability. Taking into account the risk of unintentional assessment errors, the data collected via self-assessment are analyzed and reviewed during “Enablers Assessment” and “Results Assessment”. The first of these permits is the assessment of actions. The second self-assessment presents the achieved results [

63,

64]. During the “Enablers Assessment”, one needs to seek proper answers to the following statements (see

Table 5. Enablers Assessment Scale Template presented below).

During the “Results Assessment”, one needs to seek proper answers to the following statements (see

Table 6. Results Assessment Scale Template presented below).

Both of the assessments presented above have to be supported by reliable evidence. Such evidence needs to be stored. These two assessments and corresponding evidence are a valuable source of information for external auditors.

To some extent, the MAMA model is a modification of the EU Common Assessment Framework defined as a quality management tool [

63,

64]. The innovative approach in the MAMA model is conceptualized through acceptance that the Common Anti-Money Laundering Assessment Framework is constructed as a spatial arrangement—a cuboid consisting of 8 horizontals (criteria of assessment) and four vertical areas of measuring performance, corresponding to the balanced scorecard concept. In relation to each criterion, four areas of organizational activities are linked. There are: (1) learning and growth (to achieve a vision of the organization, how will the AMLO sustain the ability to change and improve their activities?); (2) internal activities (to satisfy stakeholders and customers, what do AMLO activities have to be excelled at?); (3) customers (to achieve organizational vision, how should AMLO present itself to their customers?); and (4) financials (to succeed financially, how should AMLO appear to their decision-makers?) (Authors’ concept is based on the concept from the Balanced Scorecard Institute) [

63,

64,

65].

For each objective on the strategy map, at least one key performance indicator (KPI) will be identified and tracked over time (authors of this article did not formulate the KPI due to the fact that such indicators should be formulated for individual organizations, which are different in structure and financial sources). KPIs show progress towards a preferable outcome. KPIs monitor the implementation and effectiveness of an AMLO’s strategies, determine the gap between actual and desirable performance, and determine organization and operational effectiveness. KPIs have: (1) to provide an objective way to see if the strategy of anti-money laundering is working; (2) to offer a comparison that helps in estimating the degree of performance change over time; (3) to provide employees’ attention on what matters most to achieve success in fighting against money laundering —the best identification of suspected transactions; (4) to allow measurement of accomplishments; (5) to provide a common language of communication; and (6) to help in reducing intangible uncertainty (the authors’ concept is based on concept of the Balanced Scorecard Institute) [

63,

65,

66].

Using the modified concept of balanced scorecard [

65] enables organizations belonging to the anti-money laundering system: (1) to communicate what these organizations are trying to accomplish; (2) to align the day-to-day work that everyone is doing with organizational strategy; (3) to prioritize projects, products, and services taking into account efficient anti-money laundering; and (4) to measure and monitor progress towards strategic targets linked with AML.

The results of such an analysis carried out by AMLOs are important for external auditors. Based on them, the risk assessment of inefficient counteracting of money laundering is made. The result of the risk analysis allows the auditors to focus on those parts of AMLO activity that really need to be audited and evaluated. Due to AMLOs’ self-assessment and external auditors verifying the reliability of the analyses performed by an AMLO, a system of double reviewing of AMLO activities is created.