Solutions for the Sustainable Management of a Cultural Landscape in Danger: Mar Menor, Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Therefore, cultural heritage is not something hieratic or ancient, but must be understood as a dynamic element, one that is part of our lives, and its value contributes to society, being incorporated into our daily lives. [75].One of the main signs of identity and a testimony of the contribution made to the universal culture. The assets form an invaluable heritage and their conservation and enrichment corresponds to all the people of Murcia, and especially to the public authorities that represent them [74].

4.1. Balnearios

4.2. La Vela Latina

According to the extensive report provided by the Higher Technical School of Naval and Oceanic Engineering of the Polytechnic University of Cartagena, “Vela Latina sailing is the result of the uses and customs that involve a technical knowledge of undoubted value in the historical knowledge of navigation”. The rich cultural heritage that results from this relationship between man and the environment deserves to be taken care of and conserved, especially when many of these practices are an example of sustainability, essential even for the conservation of biological diversity [92].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística España. 30035 San Javier. Available online: http://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=28831 (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Ramsar Convention Secretariat. An Introduction to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, 5th ed.; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/handbook1_5ed_introductiontoconvention_e.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2019).

- García Sánchez, A.; Artal Tur, A.; Ramos Parreño, J.M. El turismo del Mar Menor: Predominio de la segunda residencia. Cuad. Tur. 2002, 9, 33–44. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/21981 (accessed on 8 June 2019).

- Barragán, J.M.; García Sanabria, J. Estrategia de Gestión Integrada de Zonas Costeras del Sistema Socio-Ecológico del Mar Menor y su Entorno; Consejería de Presidencia y Fomento CARM: Murcia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

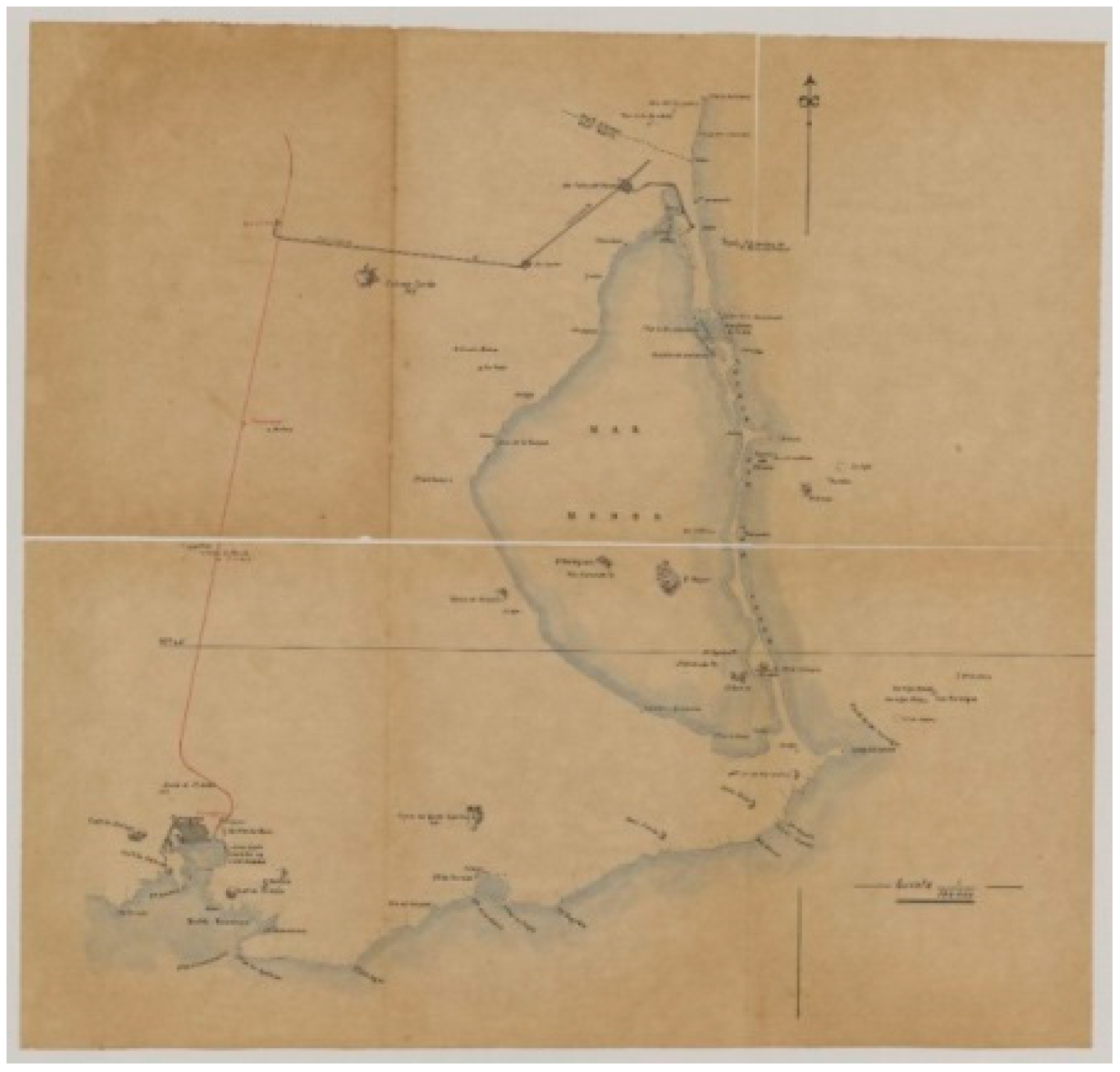

- Gustavo Gillman, B. Mapa de la Comarca del Mar Menor by Gustavo Gilman; Archivo General de la Región de Murcia (AGRM): Murcia, Spain, 1905; Gustavo Gillman Bovet, ingeniero y fotógrafo. 248.6. [Google Scholar]

- The Manifiesto de Boadilla (Boadilla Manifiesto), February 2019, was launched by the civic groups and associations that met at the 16th Jornadas en Defensa del Patrimonio Cultural de España (Conference for the Defence of Spanish Cultural Heritage), where they declared their intention to create the Federación Nacional de Asociaciones (National Federation of Associations) which would act as an intermediary with the state administrative entities. They also advocated the urgent need to undertake conservation, dissemination, promotion and educational activities with regard to cultural heritage across all tiers of society. Manifiesto de Boadilla. Asociaciones en Defensa del Patrimonio Cultural, 2019; p. 2. Available online: https://madridciudadaniaypatrimonio.org/sites/default/files/pdf-embed-blog/manifiesto_boadilla_asociaciones_en_defensa_del_patrimonio (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- author’s note: The translation of this term as bathing house does not do full justice to the architectural construction referred to by this Spanish term and described in this article, hence the Spanish term is used.

- Ashworth, G.; Voodg, H. Marketing of tourism places: What are we doing? J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1994, 6, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, S. Turismo y Gestión Municipal del Patrimonio Cultural; AECIT: Gijón, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D.C. Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2001, 7, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora Acosta, E. Sobre patrimonio y desarrollo. Aproximación al concepto de patrimonio cultural y su utilización en procesos de desarrollo territorial. Pasos 2011, 9, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.; Boyd, S. Heritage Tourism; Peqrson Education Lm.: Essex, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Rodledge-Haworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. Managing for sustainable tourism: A review of six cultural World Heritage Sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Cros, H. A new model to assist in planning for sustainable cultural heritage tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydland, L.; Grahn, W. Identifying heritage values in local communities. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L. Anfitriones e Invitados. Antropología del Turismo; Endymion: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero, C.; Garrido, M.J. Marketing del Patrimonio Cultural; Prámide: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.B.; Tresserras, J.J. Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barre, J. Vendre le Tourisme Culturel. Guide Méthodologique; Institut d’ Éstudes Superieurs des Arts: París, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.; Grimwade, G. Balancing use and preservation in cultural heritage management. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 1997, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bendix, R. Cultural tourism in Europe. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Barre, H. Cultural Tourism And Sustainable Development. Mus. Int. 2002, 54, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Hall, C. Geography, Marketing and the Selling of Places. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1997, 6, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimanche, F.; Havitz, M.E. Consumer Behavior and Tourism: Review and Extension of Four Study Areas. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1995, 3, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council On Monuments and Sites. Carta Internacional sobre Turismo Cultural La Gestión del Turismo en los sitios con Patrimonio Significativo. In Proceedings of the 12th Asamblea General ICOMOS en México, México, 17–23 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Herreman, Y. Museum and Tourism: Culture and Consumption. Mus. Int. 1998, 50, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, B.; Lord, G.D. Manual de Gestión de Museos; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, C. The Museum Environment and the Visitor Experience. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.; Rentschles, R. Changes in Museum Mnagement. A Custodial or Marketing Emphasis? J. Manag. Dev. 2002, 21, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaumier, S. Des Musées en Quête d’Identité (Nouvelles Études Anthropologiques); L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg, T. Cultural Tourism and Business Opportunities. For Museum Heritage Sites. Available online: https://www.lord.ca/Media/Artcl_Ted_CultTourismBusOpps.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Asenjo, E. (Ed.) Lazos de Luz Azul: Museos y Tecnologías 1, 2 y 3.0; UOC (Universitata Operta de Cataluya): Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moreré Molinero, N.; Perelló Oliver, S. Turismo Cultural. Patrimonio, Museos y Empleabilidad; FundaciónEOI: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://www.eoi.es/es/savia/publicaciones/20726/turismo-cultural-patrimonio-museos-y-empleabilidad (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Marchena, M.J. Turismo Urbano y Patrimonio Cultural. Una Perspectiva Europea; Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo Santos, J. El patrimonio histórico como factor de desarrollo sostenible. Una reflexión sobre las políticas culturales de la Unión y su aplicación en Andalucía. Cuad. Econ. Cult. 2003, 1, 55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, A.J. Patrimonio Histórico—Artistico; Historia 16: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Martínez, A. ¿Qué hace una chica como tú en un lugar como este?(Algunas reflexiones acerca de la relación entre Historia del Arte y Patrimonio Cultral). Artigrama 2000, 15, 543–564. [Google Scholar]

- Cuetos, P. El Patrimonio Cultural. Conceptos Básicos; Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dikovitskaya, M. Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeff, N. Una Introducción a la Cultura Visual; Paidos: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Debray, D. Vida y Muerte de la Imagen. Historia de la Mirada en Occidente; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brugère, F. Le musée entre la culture populaire et le divertissement. En quelle culture défendre? Sprit 2002, 283, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, H.I.; Manuel, G.; Santamarina Campos, B.; Moncusí Ferré, A.; Rodrigo, M.A. La Memoria Construida. Patrimonio Cultural y Modernidad; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, E.; Ranger, T. (Eds.) La Invención de la Tradición; Crítica: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Paz, E. De tesoro ilustrado a recurso turístico: El cambiante significado del. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2006, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Matías, A.R. Historia del Arte y Patrimonio Cultural de España; Sintesis: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc Altemir, A. El Patrimonio Común de la Humanidad. Hacia un Régimen Jurídico Internacional de su Gestión; Bosch: Barcelona, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrián Abellán, A. Turismo Cultural y Desarrollo Sostenible. Análisis de Áreas Patrimoniales; EDITUM: Murcia, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abad Liceras, J.M. Administraciones Locales y Patrimonio Histórico; Montecorvo: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, A. Turismo cultural, culturas turísticas. Horiz. Antropol. 2003, 20, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats, L. La mercantilización del patrimonio: Entre la economía turística y las representaciones identitarias. PH Bol. Inst. Andal. Patrim. Hist. 2006, 58, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi Vallbona, M.; Planells Costa, M. Patrimonio Cultural; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Amador de los Ríos, R. España, sus Monumentos y Artes. Murcia y Albacete; Tip. Daniel Cortezo: Barcelona, Spain, 1889. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez de Gregorio, F. El Municipio de San Javier en la Historia del Mar Menor; Academia alfonso X el Sabio: Murcia, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Fontes, J. Repartimiento y Repoblación en el Siglo XIII; Academia Alfonso X el Sabio: Murcia, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cutillas Victoria, B. Proteger y defender la Manga del Mar Menor: Estudio histórico-arqueológico de la Torre de San Miguel del Estacio y la Torre de la Encañizada. Defensive Archit. Mediterr: XV XVIII centuries. 2015, 1, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Victoria Moreno, D. Los Alcázares y el Mar Menor: El complejo tránsito a la Modernidad. En AAVV, Historia de los Alcázares; CARM: Murcia, Spain, 2008; Volume II, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Buitigieg, J. La despoblación del Mar Menor y sus causas. Bol. Pescas Dir. Gral. Pesca Minist. Mar. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 1927, 133, 251–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lillo Carpio, M. Geomorfologia litoral del Mar Menor. Pap. Dep. Geogr. 1978, 8, 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- López-Bermúdez, F.; Ramírez, L.; Martín de Agar, P. Análisis integral del medio natural en la planificación territorial: El ejemplo del Mar Menor. Murcia (VII) 1981, 18, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, I.M. Fitobentos de una Laguna Costera. El Mar Menor. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Arévalo, L. El Mar Menor como sistema forzado por el Mediterráneo. Control hidráulico y agentes fuerza. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 1988, 5, 63–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mas Hernández, J. El Mar Menor.: Relaciones, Diferencias y Afinidades Entre las Lagunas Costeras yel Mar Mediterráneo Adyacente. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Díaz, A. Belmonte SerratoF. Los paisajes geomorfológicos de la Región de Murcia como recurso turístico. Cuad. Tur. 2002, 9, 103–122. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/21931/21221 (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- Cabezas, F. Balance Hídrico del Mar Menor. El Mar Menor. Estado Actual del Conocimiento Científico; Fundación Instituto Euromediterráneo del Agua: Murcia, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baudron, P. Anthropisation d’un Système Aquifère Multicouche Méditerranéen (Campo de Cartagena, SE Espagne). Approches Hydrodynamique, Géochimique et Isotopique. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, I.A. Guerra y Decadencia. Gobierno y Administracción en la España de los Austrias. 1560–1620; Crítica: Barcelona, Spain, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Larrinaga, C. Patrimonio del sector turístico: Los balnearios. El caso guipuzcoano. Áreas Rev. Int. Cienc. Soc. 2010, 29, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.Á.; Troitiño Torralba, L. Patrimonio y turismo. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 20, 527–551. [Google Scholar]

- Dormaels, M. Identidad, comunidades y patrimonio local: Una nueva legitimidad social. Alteridades 2012, 22, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Griñán Montealgre, M.; Trigueros Molina, J.C. Patrimonio y Paisaje Cultural del agua en el Valle de Ricote. E-rph 2018, 22, 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ley 4/2007 de Patrimonio Cultural de la Región de Murcia. Available online: http://noticias.juridicas.com/base_datos/CCAA/mu-l4-2007.html (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- UNESCO. “Culture: Urban Future”. The Role of Cultural Heritage for Sustainable Local Development. 2017. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/events/1395 (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Davallon, J. Comment se fabrique le patrimoine? Sci. Hum. Hors Sér. 2002, 36, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dormaels, M. The concept behind the word. In Understanding Heritage: Perspectives in Heritage Studies; Marie-Theres, A., Roland, B., Britta, R., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Informe Final de la Conferencia Mundial Sobre Políticas Culturales; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1982; p. 7. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000052505_spa (accessed on 8 February 2019).

- Carta de Burra para Sitios de significación Cultural. ICOMOS Australia. 1999. Preámbulo. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/burra1999_spa.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2019).

- Declaración Sobre la Conservación del Entorno de las Estructuras, Sitios y Áreas Patrimoniales –Xi’an (China), ICOMOS. 22 October 2005. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/xian-declaration-sp.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2019).

- 25 Ley 16/1985, de 25 de Junio, de Patrimonio Histórico Español. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1985-12534 (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. Gobierno de España, Regímenes Especiales de Protección del Patrimonio Histórico, Madrid, Spain. Available online: http://www.mecd.gob.es/cultura-mecd/areas-cultura/patrimonio/bienes-culturales-protegidos/niveles-de-proteccion/regimenes-especiales.html. (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia. Estrategia de Gestión Integrada de Zonas Costeras del Sistema Socio-Ecológico del Mar Menor y su Entorno. Available online: https://www.carm.es/web/pagina?IDCONTENIDO=106035&IDTIPO=10&RASTRO=c$m122,70 (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Ayuntameniento de San Javier. Bienes Inmuebles Protegidos Desde el Plan General Municipal de Ordenación de San Javier. In Registro General de Bienes Culturales dependiente de la Consejería de Educación y Cultura de la Región de Murcia; Ayuntameniento de San Javier: San Javier, España; Available online: http://www.pgmo.sanjavier.es/textos/02-3-1%20Catalogo%20de%20Bienes%20Protegidos-PGMO-AP%202014.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- VVAA. El Papel de Nuestra Historia. Los Alcázares, San Pedro del Pinatar, San Javier. Murcia; Tres Fronteras: Murcia, Spain, 2009; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cegarra Beltrí, G. Arquitectura Modernista en la Región de Murcia; Mablaz: Cartagena, Colombia, 2013; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Cortines Corral, C. La Arquitectura del Agua: Los Balneario del Mar Menor. Imafronte 1990, 19, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- irección General de Patrimonio Histórico. (Consejería de Cultura y Educación de la CARM). The Proyecto de Rehabilitación de las Playas (Project for the Rehabilitation of the Beaches) was launched by the Junta de Costas (Coastal Commission), which depended upon the Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo (Ministry for Public Works and Urban Planning). Murcia, Spain. Its aim was to create artificial beaches that would facilitate bathing and the enjoyment of the seaside, and this drastically affected the traditional image of the coast and led to the elimination of the majority of the maritime buildings.

- AGRM. ES.30030.AGRM/71. 71.12./Postales y Documentos de San Javier y La Ribera (1822–1965). Serie Costa de la Luz. Available online: https://archivoweb.carm.es/archivoGeneral/arg.muestra_detalle?idses=0&pref_id=4343958 (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Decreto, n. 7/2018, de 31 de enero, del Consejo de Gobierno de la Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia, por el que se declara Bien de Interés Cultural inmaterial(BIC) la Vela Latina y los oficios y saberes relacionados con su práctica. Boletín Oficial Región de Murcia, 8 febrero. 2018, pp. 2898–2906. Available online: https://www.borm.es/services/anuncio/ano/2017/numero/1619/txt?id=755120 (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Ley 10/2015 para la Salvaguardia del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. (BOE 126, de 27 de mayo de 2015, art.1 45289). Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2015-5794 (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Available online: https://www.laopiniondemurcia.es/consejo-gobierno/2018/01/31/ (accessed on 22 September 2019).

- La Spina, V.; Serrano Hidalgo, M.C. El Modernismo en la Región de Murcia; Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, CRAI Biblioteca: Murcia, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- El Levante (Valencia). Available online: https://www.levante-emv.com/valencia/2018/12/02/vela-latina-reivindica-bic-segundo/1803368.htm (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- UNESCO. Textos básicos de la Convención del Patrimonio Mundial de 1972. Available online: http://www.icomos.es/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DIRECTRICES.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- UNESCO. Join the World Heritage Volunteers Campaign 2020. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2061 (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- UNDP. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development.html (accessed on 12 October 2019).

| BIENES | GRADO | POBLACIÓN |

|---|---|---|

| ARQUITECTURA CIVIL | ||

| Casa del Conde Campillo | 1 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Chalet Barnuevo | 1 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Hacienda de Roda | BIC | Roda |

| Conjunto de Edificaciones de la Isla del Barón | Incoado BIC | La Manga (San Javier) |

| Villa San Francisco Javier | 1 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Torre Javiera | 2 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Villa la Pinada | 2 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Casa Benimar | 2 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Torre García | 2 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Villa “El Retiro” | 2 | San Javier |

| Torre Saavedra | 3 | San Javier |

| Colonia Ruiz de Alda | 2 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Academia General del Aire | 3 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Torre Mínguez | 3 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Club Náutico | 1 | San Javier |

| Cuartel de la Guardia Civil | 2 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Casa en Paseo Colon, nº 48 | 3 | San Javier |

| Grupo Escolar San Javier | 3 | San Javier |

| Torre Octavio | 3 | La Manga |

| Casa en Veneziola. | 3 | La Manga |

| Casa de la Encañizada | 1 | San Javier |

| Casa Los Urreas | 3 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Casa en Paseo Colon, nº 46 | 3 | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Casa en Paseo Colon, nº 47 | 3 | |

| ARQUITECTURA POPULAR | Stgo. de La Ribera | |

| Noria de sangre de la Torre García | 3 | La Manga |

| Aljibe de cúpula de la Isla Grossa | 1 | |

| MOLINOS | BIC | |

| Molino de Sal | La Manga | |

| Molino de Sal | La Manga | |

| Molino de trasegar Agua | La Manga | |

| Molino Finca la Máquina | San Javier | |

| Molino de Agua | San Javier | |

| Molino de Harina | San Javier | |

| Molino de Agua | La Grajuela | |

| Molino de Agua | La Grajuela | |

| Molino de Agua | La Grajuela | |

| ARQUITECTURA RELIGIOSA | ||

| Iglesia Parroquial de San Francisco Javier | 1 | San Javier |

| Iglesia Nuestra Señora de EL Rosario | 2 | El Mirador |

| Ermita de San José | 3 | Pozo Aledo |

| Iglesia Parroquial de Santiago Apóstol | Stgo. de La Ribera | |

| BALNEARIOS | ||

| Balneario. Concesión 522 | Incoado BIC | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Balneario. Concesión 474 | Incoado BIC | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Balneario. Concesión 397 | BIC | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| Balneario. Concesión 445 | BIC | Stgo. de La Ribera |

| ÁREAS DE INTERÉS ARQUEOLÓGICO | ||

| Isla Perdiguera I - Exp.208/90 45 | C | La Manga |

| Isla Perdiguera II - Exp.830/98 46 | C | La Manga |

| La Grajuela - Exp.877/90 47 | B, C | La Grajuela |

| La Esparteña I - Exp.828/98 48 | C | Isla La Perdiguera |

| La Esparteña II – Exp.829/98 | C | Isla La Perdiguera |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montealegre, M.G. Solutions for the Sustainable Management of a Cultural Landscape in Danger: Mar Menor, Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010335

Montealegre MG. Solutions for the Sustainable Management of a Cultural Landscape in Danger: Mar Menor, Spain. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010335

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontealegre, María Griñán. 2020. "Solutions for the Sustainable Management of a Cultural Landscape in Danger: Mar Menor, Spain" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010335