1. Introduction

Enhancing adaptive capacity in natural protected areas (NPAs) requires different frameworks, since there are clear difficulties in connecting use and conservation, and there is also a gap between the planning of objectives and the management of protected areas. According to a social perspective framework, four major conflicts hinder the implementation of a management plan for NPAs: Between between uses and conservation; due to incompatibilities between different uses and activities; at the institutional and political level; and due to land-use changes [

1]. Some frameworks serve to evaluate the role of the populations and communities in participatory conservation, while others may be used to evaluate conservation supported by institutions that facilitate cross-scale and intersectoral planning. In either case, conservation of NPAs and their ecological resources and services is coproduced by humans and nature as a result of interactions between ecological functions and societal management and demand [

2]. Understanding how different social and ecological factors shape environmental conservation is essential for fair and effective policy and management. Therefore, at the heart of any local-level adaptation intervention is the need to increase the individual’s or community’s adaptive capacity [

3]. This capacity is also considered multidimensional within a complex and uncertain process because of the number of relationships and factors that act at different scales in socioecological systems (SESs) [

4]. By adaptive capacity, we refer to the ability of a system to adjust, modify, or change its characteristics or actions towards a disturbance, moderate potential damage, take advantage of opportunities, or cope with the consequences of transformation [

5]. Thus, it is a determinant of socioecological behavior of a system in response to various disturbances.

Recently, there have been different views on adaptive capacity with different approaches, contexts, and scales of analysis, which define the characteristics of the concept and its methodological application [

6,

7]. Since communities are unique and have their own local needs, experiences, resources, and ideas about prevention of, protection against, response to, and recovery from different types of changes, each community would have access to resources and the ability to manipulate and make decisions that single individuals do not. Therefore, community adaptive capacity is highly location-specific [

8]. A community-level focus on adaptive capacity—as opposed to a “one-size-fits-all” or “top-down” approach—results in local participation, ownership, and flexibility in building adaptive capacity. In this sense, strengthening local coping capacity can help empower local communities rather than foster institutional dependency [

9].

Through efforts to systematize reference frameworks, conceptual and methodological approaches, specific experiences in projects, and lessons learned about adaptation and development in case studies, resilience has been recognized as the closest concept, complementary to—and, to a large degree—overlapping with that of adaptive capacity [

10]. However, most socioecological frameworks developed to date lack clear operational linkages between humans and nature to efficiently guide SESs toward a key component of complex adaptive systems—resilience [

11]. Particularly, existing cases of resilience practice in natural resource management confirm that resilience can contribute to the understanding and adaptive governance of complex socioecological systems [

12]. Studying the key processes underlying the interaction dynamics, especially those leveraging adaptive management processes, would help identify adaptive pathways for practices and collective actions, provide a crucial knowledge base for policy makers, and foster operationality as a requisite of an SES research agenda [

11].

The conceptual framework of resilience practice refers to applications of resilience thinking in different real-world settings, i.e., non-academic contexts and research–practice interfaces, such as resilience assessment, planning, management, and action [

12]. In this sense, there is an increasing demand for practical approaches to resilience, for example, in urban planning and environmental management. We belief that to look at local adaptive capacity would be of doubtful practical utility, as a community’s ability to respond to environmental changes depends, at least in part, on underlying drivers of poverty and vulnerability (e.g., levels of economic resources and the effectiveness and flexibility of local institutions), and on factors that both influence and are highly influenced by them (e.g., the willingness of a community to innovate) [

3].

From a resilience approach, it is believed that the preservation of traditional peri-urban landscapes depends on their capacity to adapt to new challenges without altering their essential characteristics [

13]. Since peri-urbanization processes bring new challenges to governments and local communities of peripheral territories, stronger capacities to deal with economic, social, and environmental impacts such as rural and urban in-migration, land speculation, conversion of agricultural and forestry land into urban uses, negative environmental externalities, and de-territorialization and re-territorialization of livelihoods are required. Therefore, collaborative social networks, established inside the organization as well as in its institutional context, seem to be crucial for better solutions for the benefit of people [

14]. In peri-urban landscapes, common assumptions about the values, activities, land use, and social organization of rural or urban populations may not be valid, and policies for addressing the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of these populations to risks and changes may be ineffective. As the relationship of residents to their landscapes changes, these peri-urban spaces pose new institutional challenges for social–ecological planning [

15].

Meanwhile, research worldwide on factors that affect NPAs has traditionally focused on natural ecosystems [

1], complex environmental and territorial systems far from urban centers. The term urban protected area is not common in the literature, and the processes of deterioration of protected peri-urban ecosystems and the effectiveness and functioning of peri-urban NPAs are scarce or poorly reported. The main documented deterioration factor is the urbanization of rural areas adjacent to cities, which introduces changes in the ecological function of protected areas, loss of their biodiversity, change in land use, conflicts with wildlife, introduction of invasive species, vandalism, and noise, among others [

16]. In addition, there is a lack of information on integrated policies, effective intersectoral coordination, and instrumentation for monitoring purposes on peri-urban NPAs.

In Mexico, diverse strategies have been promoted towards conservation and protection of the environment, particularly in NPAs. Mexico’s environmental policy includes the creation of the National System of Protected Areas (SINAP) within the National Program for Environmental Protection. An NPA is defined as a geographical and legal territory designed to conserve ecosystems altered to a greater or lesser extent by humans [

17]. These areas are essential for biodiversity conservation in a mega-diverse country like Mexico [

18], as they activate flows and ecological cycles that provide ecosystem services to society. NPAs are crucial for nature conservation and vital to the cultures and livelihoods of indigenous and local communities [

19,

20].

In Mexico, NPAs are defined as areas over which the nation exercises sovereignty and jurisdiction, as appointed by presidential decree and supported in the General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection (LGEEPA) [

21]. From different perspectives, NPAs correspond to a gradient—from confined spaces, to those where there is a significant cultural component, and even where sustainable resource extraction is allowed [

22].

Mexico has 182 NPAs, which cover an area of 90,839,521.55 hectares, supported in 339 voluntarily designated conservation areas that cover 506,912 hectares, representing approximately 12% of this country [

23,

24]. Despite the significant growth in number and territory of the NPAs, a number of limitations associated with effective management and conservation have been identified; particularly, the need to strengthen the management of environmental sustainability: Focusing on the declining environmental quality in ecosystems, problems associated with land-use change, degradation, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity conservation.

In Mexico, 60% of NPAs are socially owned, 20% are federally owned, 12% are privately owned, and 8% are not yet determined [

25]. Some of the communities that manage these spaces have oriented them towards ecotourism as an economic development strategy. These social features commonly go unnoticed in public decision-making, where the Western conception of isolation between society and its natural environment is still perceived. In Mexico, most NPA plans or public decisions do not include communities and their current problems, since most approaches are top-down (government to community) and do not take into account the specific components of each locality.

One of the largest NPAs in the central region of Mexico is the Iztaccíhuatl Popocatépetl National Park (NP Izta-Popo), nestled in the center-east of the Transversal Volcanic Axis, which includes urban and peri-urban centers that together reach up to 25 million inhabitants, and is considered a strategic area because of its hydrological and forest reserves. The NP Izta-Popo represents a current opportunity of intervention in the face of new challenges posed by climate change and risk associated with urban growth and environmental crisis. In this sense, it is a priority to consider the fundamental criteria of adaptation to reduce negative impacts on this NPA under the framework of inclusion of local communities and their efforts to strengthen the conservation of their resources and to promote their local development potential.

This article assumes that for conservation and ecosystem management of an NPA, traditional knowledge and community participation constitute the main grounds to improve the capacity of local communities to adapt to changing dynamics and decrease risk processes. We present the results obtained by applying collaborative processes of knowledge co-production with a community that is part of an NPA—NP Izta-Popo—that performs various types of natural resource management in the peri-urban area of Mexico City.

2. Materials and Methods

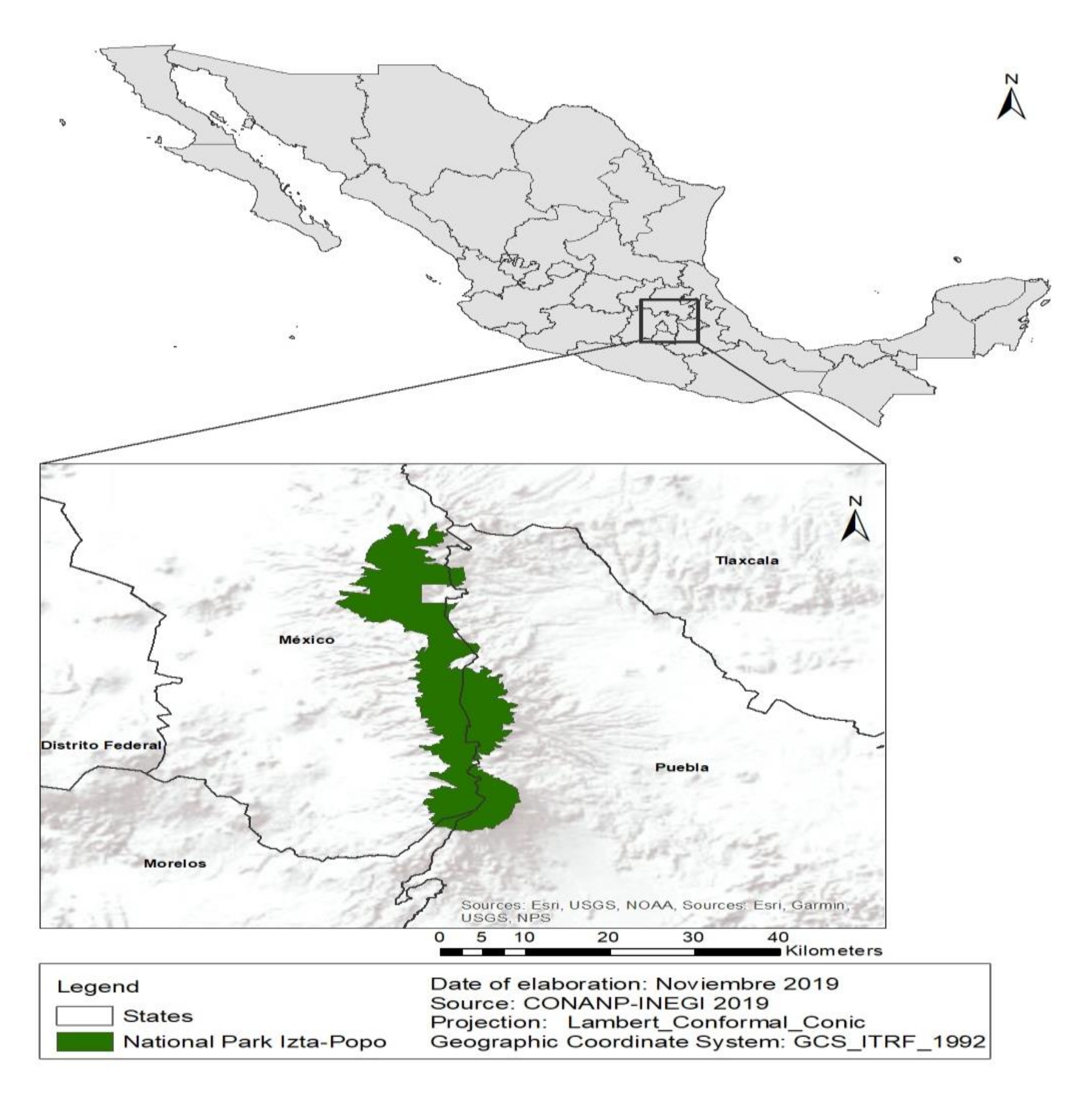

NP Izta-Popo (

Figure 1) has been one of the areas with the greatest historical significance in Mexico since its declaration on 8 November 1935. This national park (NP) was envisioned as an engine for development, given its capacity to provide water, energy, and wood as ecosystem services. At NP Izta-Popo, the term “conservation” was understood as the challenge to maintain productive landscapes where nature and culture intermingle [

26]. The main goals of this NP are the protection and conservation of the mountains that form the Sierra Nevada in the eastern center of the Transversal Volcanic Axis. In 2010, it was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve of Volcanoes; this declaration implies an international recognition of the importance of this territory for the conservation and protection of biodiversity. The NP has an area of 39,819 hectares [

27]; land tenure is ejidal, (an ejido is a social, rural, and collective property in Mexico with legal personality and its own assets, which operates according to internal regulations for economic and social organization), communal, private, and federal [

28]. It is a high mountain ecosystem, with an altitudinal range of 2589 to 5454 m above sea level. As a whole, NP Itza-Popo is the most important remnant of coniferous forests and high mountain meadows in the center of Mexico.

There are 1,559,796 people in 808 communities within the area of influence of NP Izta-Popo [

27]. Most of these communities are engaged in agricultural and livestock activities, while some communities have begun to develop projects aimed at conservation, such as ecotourism. Most of these activities are carried out under the figure of the

ejido. Adjacent to NP Izta-Popo is our case of study, the ejido Emiliano Zapata, founded in December 1999, with an area of 96.7 hectares and a total of 27

ejidatarios (ejido farmers). It belongs to the town of San Nicolás Cuiloxotitla, State of Mexico.

Initially, ejidatarios were engaged in agricultural activities of planting corn and fodder; however, they faced problems, such as soil erosion, pests, early frosts, diseases, invasion of harmful fauna, and grazing of cattle, which caused low profitability in agricultural production. In 2012, the ejidatarios decided to form the Emerald Forest group as an ecotourism park under a vision of sustainable development supported by four environmental, social, educational–cultural, and economic axes. As a local social enterprise, Emerald Forest develops community-planning processes; among these is a zoning use survey. The current zoning of the common land (ejido) is composed of protected, restoration, conservation, and sustainable use areas (i.e., Christmas tree nurseries and ecotourism activities of the forest park). The main community activities are aimed at the conservation of the regional socioecological system in which they live, given the importance of the natural resources.

The design of this research takes up the conceptual model of adaptive capacity management in socioecological systems from a participatory approach [

29]. Particularly, our approach is comparable to existing approaches that seek to understand the systemic challenges and opportunities as well as their interrelatedness with socioecological systems in order to implement potential solutions in an inclusive, participatory manner from the perspectives of multiple system actors [

30]. The research fieldwork was done in 2016. The first part of the research included a review of documents and the inclusion of general, regional, and local mapping interviews (six) and meetings (two) with local decision-makers to delineate the regional framework and to discuss the vision of resources and problems. Interviews have been reported as a valid instrument to identify which factors affect the deterioration of peri-urban NPAs [

16]. The second part involved a participatory diagnostic workshop on 4 February 2016, which provided an understanding of regional problems through the participation of local actors and key informants for collection of narrative data, which was a search for meaning and multiple realities. Data collected through a participatory diagnostic workshop have been used for studying resilience in NPAs [

24].

The workshop included six participatory assessment activities with the participation of 20 of the 27 total ejido members over eight hours of work. The participatory assessment activities included: (1) Mapping of context, resources, and problems; (2) historical analysis and climate trends; (3) mapping of institutions and actors, including a Social Network Analysis; (4) matrix of risks and threats; (5) adaptation strategies; and (6) strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. Each of these components is described in more detail below.

The context mapping was aimed at establishing a description of the system and key processes (physical and social): Ecosystems, structures, and actors. This step identified the issues that are considered most relevant, some of them facing the deterioration of the natural system because of their anthropocentric character.

Historical analysis and climate trends identified the main historical and past climatic events and their consequences. The changes that have occurred and how they have affected the life of the community are illustrated. In addition, oral history was collected on historic trends in regional and local change from the collective memory about extreme events in the past. Before the activity, four categories of analysis were defined corresponding to socioecological system components in order to study adaptive strategies (biophysical, political–institutional, sociocultural, and economic–productive).

Mapping of institutions and actors, which included a Social Network Analysis using GEPHI 0.9.1 software, was a key element in the strengthening of adaptive capacity, the importance of management, and the role of institutions in terms of identifying support networks and local population interactions. In particular, it has been reported that social network analysis undertaken with regard to natural resource management issues in peri-urban landscapes is useful when community groups contribute to landscape-scale ecological change through their aggregation of local ecological knowledge [

31]. In our study, in order to establish the institutions and their networks with the local community, a mapping of institutions aimed at identifying internal and external actors to know the influence in decision-making and power and establish relationships between different organizations was carried out.

During fieldwork, institution type was recorded based on its economic–productive, social, and ecological activities and institutional support profile. In this mapping, relationships differed (line types) in some of these connections established between institutions and actors, with a weight based on the significance and importance of each of these according to the consensus of the community. This type of analysis is useful in determining the adaptive capacity based on stakeholders’ identification, participation of different groups in local planning processes, and the structure of institutions and their functioning with communities. Institutional and stakeholder analyses help to detect institutions and their relevance for training and networking, which allows the development of organisms necessary to potentiate the results of an initiative with comprehensive proposals and meet the objectives of all participating entities.

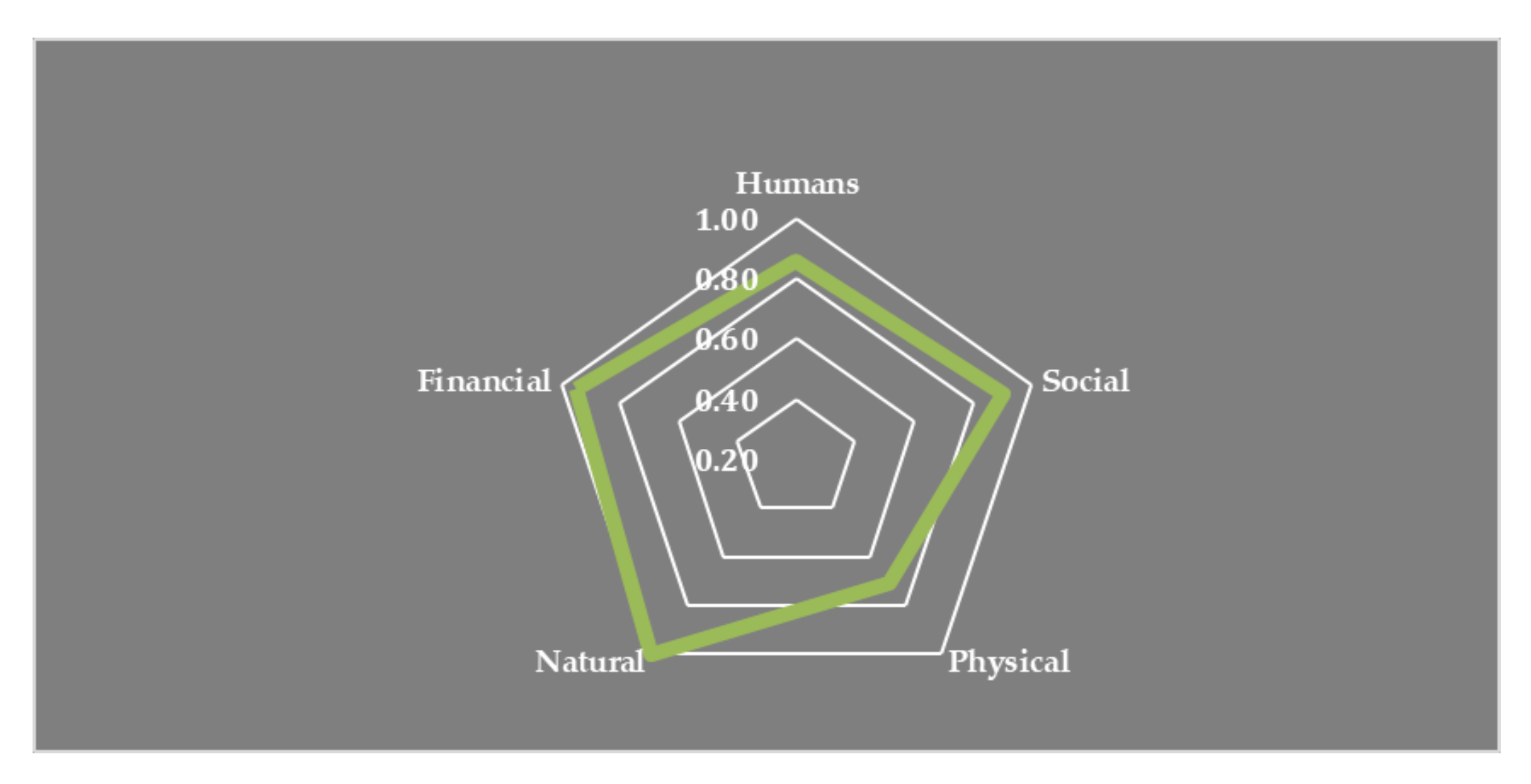

To achieve a finer analysis pattern of the local community’s adaptive capacity, including the identification of risks and threats, different matrices of risks and threats were applied. The first one helped to create a list of risks and threats that the community faces and their relationships with each of the systems that make up the livelihoods (human, social, physical, natural, and financial). This list was the result of a process of debating arguments and facts. Once risks and threats were identified, affecting values were established for each system. With the results in this matrix, we built a radar chart that visually displays the categories that require greater attention in the context of risk and threats, since they were assigned a higher value on the level of involvement.

One of the key objectives of the workshop was to know the set of adaptation strategies carried out in accordance with the list of risks and threats detected, which, as noted in the previous paragraph, are deeply connected with the construction of this matrix. Adaptation strategies focused on meeting four key points: The first one has to do with those affected by the collective judgment; the second has to do with the consequences or damages that the risk or threat brings; and the third and fourth ones aim to know the answer and the series of actions to strengthen that answer, respectively.

Through collective discussion, we established the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT analysis) that were defined by community participants to establish a scheme of capacity adaptation and elements for strengthening it. SWOT analysis is a strategic planning tool that allows the definition of a situational diagnosis for the identification of elements and implementation of strategies to facilitate stakeholder decision-making, and it aims to improve the system by reducing the weaknesses and threats presented by the system. It is important to recognize the value of the SWOT analysis, which is largely to support the construction of future scenarios based on current performance with the knowledge of internal and external environments and to establish priority strategies to promote future scenarios with better prospects.

3. Results

3.1. Mapping Context: Resources and Problems

The results of the mapping exercise helped visualize a current account of the vast resources of the region—mention was made of the number of species of flora and fauna that can be found in addition to the water resources that are available thanks to the topographic and climatic conditions. Some of the socioecological problems that people face, such as illegal logging, uncontrolled tourism, pests, grazing, and forest fires caused by the owners of grazing animals, became evident. The region was mapped with roads, land-use types (e.g., protection, restoration, conservation, harvest), and threats (e.g., conflict) placed in a regional context by a park guard. Some of the responses raised by the participants were the establishment of forestry action programs, regulation of areas of reforestation and monitoring, improvement of the protection of wild areas, establishment of connections between protected areas, strengthening of environmental education for local visitors, raising awareness with visual communication processes, and surveillance of restoration areas. A local map was drawn, offering more detailed information on land use and threats.

Likewise, by means of participatory cartography, geographic areas and possible tourist circuits were defined that promote the development of activities related to rural tourism from the perspective of local actors. It has been mentioned that local knowledge is relevant in the analysis, design, instrumentation, and evaluation of rural tourism based on community-based proposals that contribute to sustainable local development in NPAs [

32]. This community makes use of its natural resources to promote nature tourism, which is one of the key ways of conserving the natural heritage and promoting conservation through reuse of materials and applying energy-saving technologies that use renewable energy (i.e., photovoltaic systems, rainwater capture, firewood saving stoves, and dry toilets). In addition, environmental education workshops are offered, which are a source of income and promote community stewardship of the natural conditions, resources, and landscape value.

At the institutional level, the importance of the natural systems included in NP Izta-Popo was recognized, but their deterioration was also noted. A list of the main manifestations and impacts on the NPA was created, and, in all cases, it was agreed that the reduction and disappearance of glaciers was the most important at the institutional level, precisely because it is linked to the decrease in aquifers and water volume. From a university study in April 2020, it was reported that 12 glaciers of a total of 16 of the Izta-Popo volcanoes have disappeared in the last 15 years due to climate change, which has reduced meltwater from the two volcanoes, affecting the inhabitants of the area who depend on these water sources [

33]. Undoubtedly, we agree that glaciers should be considered as analogous to endangered umbrella, keystone, and flagship species whose conservation would secure wider environmental and social benefits at different scales [

34]. The risk and vulnerability detected by decision-makers were related to the decrease in water availability; thus, all respondents agree that it is the priority issue.

3.2. Historical Analysis and Climate Trends

The participants established the period 1950–2010 as critical, although the higher contribution was concentrated in the 90s and during the decade starting in 2000. In addition to local events, there was also mention of events at the regional scale—for instance, the 1985 earthquake had an impact on the sociocultural level because it caused the population of central Mexico City to move to outlying areas, one of which was the east area adjacent to NP Izta-Popo. This implied the creation of informal human settlements (1990) such as Valle de Chalco, an event that increased pressure for change of land use from agricultural to urban, promoted largely by political institutions related to housing issues. The intervention of the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP, acronym in Spanish) in the NP Izta-Popo began in 2000, so it is an important step in the start of conservation projects, including works of reforestation in degraded areas, conservation works of water and soil, and species monitoring; it also generates sociocultural changes due to the implementation of environmental education and training for peri-urban communities near NP Izta-Popo by the Program for the Protection, Restoration, and Conservation of Natural Resources (2001).

The closure of NP Izta-Popo during 1994 to 2004 due to significant volcanic activity represented a major event that impacted social and natural resource conservation activities. Park closure due to this volcanic activity contributed to ecological deterioration of the area. Reduced surveillance of the park due to its closure favored processes of corruption, including some illegal logging and induced forest fires. In contrast to the version of local people, CONANP states that the volcanic activity led to some of the park remaining closed to the public, which paradoxically allowed the recovery of zone ecosystems. Commercial chains of national and foreign wholesalers arrived in the region (2004), changing regional food consumption patterns. Later, the NP Izta-Popo was declared by UNESCO as a Biosphere Reserve of Volcanoes (2010), and a Management Program Izta-Popo was proposed (2013).

3.3. Mapping of Institutions and Actors

This exercise differentiated between the institutions inside and outside the community; thus, the community presents an established organization that they began forming years ago, which is why the location of their own organization facilitated the exercise. The organization of these institutions is related to their economic–productive, social, and institutional support activities.

Figure 2 shows the importance of institutions, in the first instance, within the community where the structure that the

ejidatarios have formed stands out; secondly, the institutions and actors outside the community are presented, and it can be seen that the community gave an important weight to tourists and visitors; since there is a link between them and the economic activities of the ecotourism park, an important weight of federal institutions, which have to do directly with support for productive projects towards the ejido, is also observed.

One of the key relationships in this mapping was between the CONANP and Pro-Forest, while other relationships with diverse institutions are observed very close to the area of decision-making that takes place within the community. It is important to highlight the participation and weight that the community gives to the academic and social welfare institutions and the fundamental role of tourists, neighbors, and families in the community (

Figure 2).

As was observed in the mapping exercise, each institution received a relative weight, which has to do with the importance given to it by the members of the community; this analysis should be carried out when one wants to apply a community-based initiative. In this sense, under the conventional institutional management approach, the increase in governance is sought to improve control of the process. A complementary form is governance, understood as the set of collective rules and processes of decision-making concerning dilemmas and problems that arise from the use, appropriation, and conservation of natural resources, as it is a basic element of adaptive capacity. According to the networks elucidated (

Figure 2), in order to consider the social rules and relationships that may influence local community-based conservation outcomes in a more systematic manner, three waypoints may be applied: (1) Think about the networks in which they are embedded and the constellation of actors that influence conservation practice; (2) examine the values and interests of diverse actors in governance and the implications of different perspectives for conservation; (3) consider how the structure and dynamics of networks can reveal helpful insights for conservation efforts [

35].

In this sense, by performing a social network analysis to detect the most connected institutions and actors (i.e., grades) as well as the shortest paths between centralities, we found that most of the connections are related to the Ejidal Commissary Communal Administrator (

Table 1), which may mean that the

ejidatarios are still depending on internal decision levels to manage their resources. However, it is notable that the actions of external stakeholders involved in this NPA are subject to the transformations of local communities in terms of seeking benefits and alliances in accordance with participation agreements in development and conservation programs and projects. This means that, although these projects were not initially intended to consolidate local communities, they do seek adaptation to regional urbanization processes through negotiation and resource management. This trend is similar to two recently reported case studies [

36].

3.4. Matrix of Risks and Threats

This exercise contributes to the definition, establishment, and redesign aimed at strengthening local adaptive capacity proposals. From this perspective, we see that the population considers the natural system the most vulnerable to the risks and threats; therefore, it is defined as a priority for attention. This result is linked to the close sensitivity between the community and the natural assets of the area, especially in the economic activities of conservation and promotion of the ecotourism park, Emerald Forest. Such a socioecological trend is similar to several cases in Mexico, where there are rural community dynamics that intertwine the use of forest resources through the creation and operation of a system of natural resources for common use in the ejido with the policy of conservation of natural heritage through protected natural areas [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Among the risks and threats detected in our case study, the important link between economic activities and ecological components can be highlighted; the latter is largely due to the close sensitivity that exists between the NP Izta-Popo, all its natural assets, and communities nearby who base their economic dependence (income and employment) on natural resource management. Another element that stands out from the analysis of risks and threats is the fact that climate change factors do not have a transcendental weight for the community, despite the fact that this NPA is one of the most sensitive areas, according to studies [

31,

42,

43] aimed at determining its risk and vulnerability due to climate change according to its characteristics, such as the presence of volcanic activity and the existence of glaciers, as well as soil erosion, where the effects of climate change can be more directly evidenced.

Figure 3 shows that the population considers the natural system more vulnerable to the risks and threats detected and, therefore, this can be established as a priority of attention for the strengthening and construction of adaptive capacity. The excessive exploitation of natural resources and the change of use of forest land to agricultural and livestock activities are critical problems that are evidenced daily by actors who live in the region; by presenting an important root in the area, they make themselves evident and take an important place within the collective consciousness.

During the workshop, the broad knowledge that the community has about its environment, climatic patterns, and natural, historical, and social landscape value was observed. Likewise, it was identified that the community has an interest in joining institutions and in the operation of programs and projects, largely to seek support for productive projects, where social organization stands out as a key to obtaining resources and promoting actions. A fundamental part of social participation and organization has to do precisely with current and future adaptation strategies, which are the set of responses that the community gives to an event of risk and threat. It has been reported that participatory scenario planning (PSP), particularly when tailored to shared objectives between local people and researchers, has enriched environmental management and scientific research through building common understanding and fostering learning about future planning of socioecological systems. However, PSP still requires greater systematic monitoring and evaluation to assess its impact on the promotion of collective action for transitions to sustainability and the adaptation to global environmental change and its challenges [

44].

To have deeper information on the behavior of the values in

Table 1, the average and the standard deviation of the risk and threats detected by the community and the data for livelihood categories are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

A key part of social participation and organization has to do with adaptation strategies, which are the set of answers given by a community in the event of risk and threat; so, it was also necessary to know what these activities are, the period in which they apply, and the actions to strengthen those answers.

3.5. Adaptation Strategies

Reported in

Table 4 are the disaggregated adaptation strategies in accordance with the list of risks and threats that have to do with the implementation of livelihoods, actions, and community awareness for short-term answers, while actions requiring longer durations, such as training, strengthen the answers, but require organization and searching for legal instruments. It is important to recognize adaptation strategies by community members in any context where it is intended to establish an adaptive capacity model; however, it is also necessary to know the adaptation measures observed and applied from the institutional level. Part of the results of the interviews is oriented in that regard.

Table 4 reflects, on the one hand, the adaptation measures observed by the community; mostly, there is mention of changes in much more conscious modes of consumption and formation of committees that promote social participation. On the other hand, institutional measures to increase adaptive capacity have been directed towards the promotion of environmental education programs, social programs, and the application of ecotechnologies. Examples of these ecotechnologies undertaken by the communities include: Rainwater harvesting programs, campaigns for the reuse of Christmas trees, building an artificial lake with rainwater, and building dry baths where there is no drainage.

3.6. SWOT Analysis

According to the SWOT analysis, two priority areas of management were defined for this case of study:

(1) Institutional coordination and community development, which include three action guidelines: (a) Institutional strengthening is required to link local governments, management institutions, and agencies involved in decision-making regarding the conservation and protection of NPAs; (b) design of community development strategies that allow the construction of networks or social exchange and economic cooperation organizations that allow an integration of knowledge with related objectives, where it is possible to develop comprehensive proposals that meet the objectives of all actors; (c) generate strategies and mechanisms for linking and collaborating with institutions associated with local problems, such as universities and research centers.

(2) Conservation projects in the NP Izta-Popo, which include the following: (a) In coordination and integration with the previous products, promote investment in research, training, and technological development programs of short-, medium-, and long-term impact with works of soil conservation, reforestation, and use of ecotechnologies, among others; (b) promote actions that counteract and prevent clandestine logging and forest fires, as well as surveillance and continuous review of agricultural and livestock techniques in the areas of influence and damping of the NPA and nearby communities; (c) generate of an effective and quality permanent system for training and technical advice that considers aspects of environmental education and the promotion of cultural activities associated with the conservation of the NPA.

Currently, the Bosque Esmeralda community has established itself as a cooperative society with recreational and ecotourism activities of the Izta-Popo NPA (see

Figure 4). This community has collaborated with public organizations and institutions for the expansion of their equipment, as well as the development and installation of new eco-technologies. Since the reforestation, maintenance, and forest soil conservation works began in 2011, the protection of the Fireflies Sanctuary has been promoted, which represents the main natural touristic attraction of the site, having had the Environmental Management Unit registered before the environmental authorities in 2018. In these almost ten years of transition in moving from an agricultural zone to an ecological, the community has strengthened their livelihoods based on their beliefs that the protection and conservation of natural resources and their SESs have to be to promoted among the visitors of the area and the local population.

4. Discussion

In peri-urban areas, built and natural systems, including ecological and productive systems, ecosystem services, infrastructure, and urban equipment, are mutually dependent. Under this framework, it is necessary to understand what or who needs to be part of the adaptive capacity strengthening with respect to synergies and resulting, at the regional and local levels, from the relationship between the environment and the socioeconomic characteristics of their own multifunctionality [

8]. According to this, by applying a pre-eminent socioecological approach in local community adaptive strategies, through an integrated management of the territory, the appropriate conservation and restoration actions should be harmonized with the productive activities on which the local economies depend for the sake of local livelihoods. In particular, it is necessary to identify what capacities must be maintained and recovered from the direct and indirect impacts of changes that contribute to the transformation of peri-urban NPA; for example, urbanization trends, infrastructure provision, land use, and production and consumption patterns, including the agro-productive, forestry, and ecotourism systems, such as they are reported in this study.

There is a growing need to expand the conceptual and methodological approaches to incorporate the local knowledge of populations in processes, strategies, and actions of local and regional planning, which contribute to environmental conservation and the reduction of variables that represent risk, threat, or vulnerability from a socioecological vision that precisely integrates these two spheres (social and environmental or ecological) and their components. Therefore, in order to approach the adaptive capacity of local actors for changes in peri-urban geographies from the perspective of adaptive socio-environmental governance, it is possible to propose: (1) Include all of the actors and decision makers; (2) create processes for monitoring and social learning through local, scientific, and political sources of knowledge production; (3) maintain collaborative networks of the different actors of governance and the strengthening of adaptive capacity across geographical scales. In this sense, it is relevant to study the dynamic change of these geographical landscapes and the importance of multi-stakeholder frameworks in the management of peri-urban NPAs.

From a methodological point of view, establishing an analysis of adaptive capacity with community participation permits preliminary identification of the techniques, knowledge, tools, and instruments traditionally applied by a community in the face of risk variables. This also provides insight into the details of the variables fed by the group’s vision and opinion, and allows for a review of the processes and state of decisions leading to the inquiry about institutions and bodies of government in charge of policy and the management of socioecological problems. This type of analysis becomes an opportunity that may integrate areas poised to strengthen adaptation strategies and risk prevention, potentially anticipating changes ahead by factors such as climate change, climate variability, the growth of cities, deforestation, etc.

Measures aimed at adaptation should focus on multiple levels and incorporate different strategies [

36] to help obtain inputs for generating proposals that either design dynamic adaptation plans or determine measures to increase adaptive capacity. The following conceptual and methodological considerations for the study of adaptive capacity emerge from experience in the community of Ejido Emiliano Zapata (Emerald forest), adjacent to the NP Izta-Popo in peri-urban Mexico City:

Systems with a larger number of components (species, actors, sources of knowledge, etc.) tend to have greater adaptation capacity.

Well-connected systems are more likely to recover from disturbances, although, sometimes, highly connected systems can cause rapid dispersion of such disturbances along them. Connectivity between an NPA and its areas of influence (in this case, urban areas) increases the resilience of systems, both ecological and human [

38].

Promote recognition that socioecological systems consist of multiple connections occurring simultaneously at different levels and scales (i.e., local government).

Learning and experiences through adaptive management and social innovation are important mechanisms for socio-ecosystem adaptations. These mechanisms ensure that different types of solutions and sources of knowledge, valuations, and social practices that come together among groups and organizations, which have socio-historical knowledge about the trajectory of the transformations from the direct and indirect drivers on local SESs, are considered in adaptation development [

39].

Include different sectors/actors in decision-making, conservation plans, and actions to enrich prospects, and provide information that cannot be acquired exclusively by generating scientific knowledge.

It should be noted that it is necessary to create an enabling environment for community adaptation, mainly from participatory approaches. The set of methodological guidelines allows us to establish a potential system of intervention in natural areas, such as the NP Izta-Popo, taking into account community participation, components of each system, the causes that lead to and maintain conditions of vulnerability, and policies and programs that play an important role in determining adaptive capacity and resilience at the local level. However, in this research, we agree that there are significant challenges to be addressed in achieving equitably managed NPA, particularly in ensuring effective participation in decision-making [

45].