How Can Travel Agencies Create Sustainable Competitive Advantages? Perspective on Employee Role Stress and Initiative Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influence of Market Orientation on Role Stress

2.2. Influence of Role Stress on Organizational Citizenship Behavior

3. Methodology

Data Collection

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

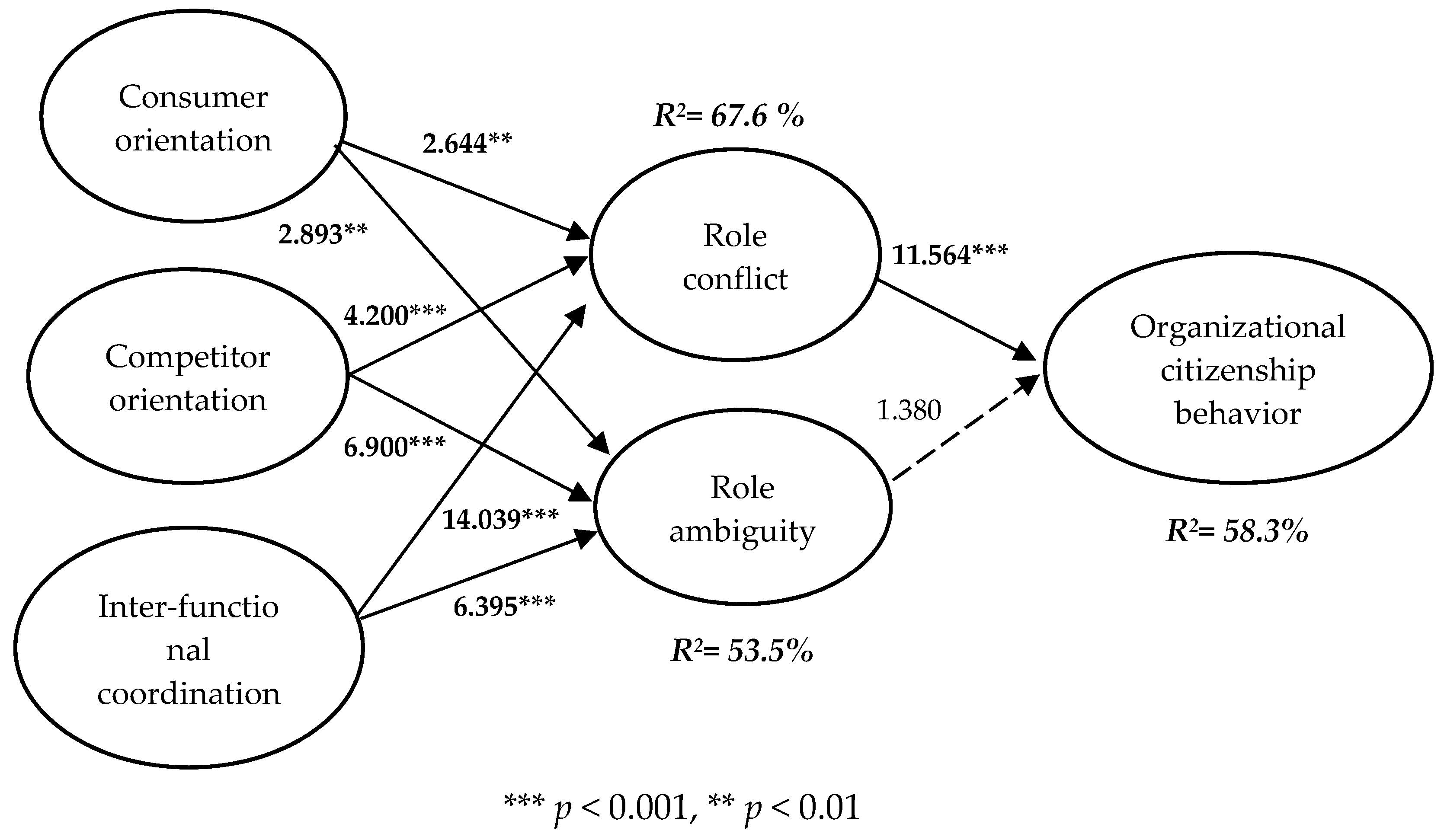

4.2. Structural Model

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Scale Development

| Factor | Item Description |

|---|---|

| Consumer Orientation (CO) | Our company emphasizes the commitment to customers. |

| Our company is committed to creating customer value. | |

| Our company will set customer satisfaction goals. | |

| Our company usually measures customer satisfaction. | |

| Competitor Orientation (CPO) | Salespeople usually share competitors and market information. |

| Our company can quickly respond to competitors’ threatening behavior. | |

| Top management often discusses competitors ’advantages and strategies. | |

| Competitor’s behavior is the basis for our company’s strategy. | |

| Inter-Functional Coordination (IFC) | Our company emphasizes cross-functional customer response. |

| Each department of the company shares information and resources with each other. | |

| Our company has a cross-functional strategy integration. | |

| Role Conflict (RC) | I have to deal with many different natures of work while working. |

| I was assigned to lack of enough manpower and resources to complete. | |

| In order to perform work tasks, I often have to violate the company’s rules or policies. | |

| I often receive contradictory job requests from my boss or colleague. | |

| Role Ambiguity (RA) | I clearly realize my permissions. |

| I understand my job responsibilities. | |

| I exactly know what others expect from me while working. | |

| My supervisor clearly explains what I should do. | |

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) | I use initiative to guide new colleagues to adapt to the working environment. |

| I use initiative to share responsibilities or fill in for colleagues concerning working stuff. | |

| I never select the job tasks, but I am willing to accept new or difficult tasks as much as possible. | |

| I strive to maintain the company’s image and actively participate in related activities. |

References

- Hu, H.H.; Hu, H.Y.; King, B. Impacts of misbehaving air passengers on frontline employees: Role stress and emotional labor. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1793–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D.; Endang, S.; Khasbulloh, H. The Impact of Job Satisfaction, Organization Commitment, Organization Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) on Employees Performance. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2016, 9, 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- Callea, A.; Urbini, F.; Chirumbolo, A. The mediating role of organizational identification in the relationship between qualitative job insecurity, OCB and job performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Mehta, S. antecedents and consequences of organizational citizenship behavior: A conceptual framework in reference to health care sector. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 10, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleke, O.B.; Jianguo, D. When the good outweighs the bad: Organizational citizenship behavior in the workplace. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemian, S.; Abdul Rahman, R.; Mohd, S.Z.; Adewale, A. Role of market orientation in sustainable performance: The case of a leading microfinance provider. Humanomics 2016, 32, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, C.; Ingram, T. Ethical leadership in the salesforce: Effects on salesperson customer orientation, commitment to customer value and job stress. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablah, A.R.; Franke, G.R.; Brown, T.J.; Bartholomew, D.E. How and When Does Customer Orientation Influence Frontline Employee Job Outcomes? A Meta-Analytic Evaluation. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersson, L.M.; Bateman, T.S. Cynicism in the workplace: Some causes and effects. J. Organ. Behav. 1997, 18, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, A.H.; Christian, K.; Michael, J.G.; Jason, S. The Impact of Vocational and Social Efficacy on Job Performance and Career Satisfaction. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2004, 10, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.H.; Valentine, S.R. Cynicism as fundamental dimension of moral decision-making: A scale development. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 34, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C. The Effect of Role Stress on the relationship between Internal Marketing and Customer-oriented Behavior: The Case of Food Service in Taiwan’’s International Tourist Hotels. Unpublished. Master Thesis, National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, R.F.; Hult, G.T.M. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. The resource advantage theory of competition: Dynamics, path dependencies, and evolutionary dimensions. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Customer-led and market-oriented: Let’s not confuse the two. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Myagmarsuren, O. Exploring the moderating effects of value offerings between market orientation and performance in tourism industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, A.; San, M.H.; Collado, J. Market orientation and SNS adoption for marketing purposes in hospitality microenterprises. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 34, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, C.W.L.; Jones, G.R. Strategic Management: An Integrated Approach; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas, B.A. Strategy Type, Market Orientation, and the Balance Between Adaptability and Adaptation. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 45, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R. Market Orientation and Organizational Performance Linkage in Chinese Hotels: The Mediating Roles of Corporate Social Responsibility and Customer Satisfaction. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prifti, R.; Alimehmeti, G. Market orientation, innovation, and firm performance—An analysis of Albanian firms. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bader, Y.O. The Effect of Strategic Orientation on Organizational Performance: The Mediating Role of Innovation. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Syst. Sci. 2016, 9, 478–505. [Google Scholar]

- Day, G.S. The Capabilities of Market-Driven. Organizations. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Gupta, M.C. A perusal of extant literature on market orientation—Concern for its implementation. Mark. Rev. 2010, 10, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L.; Wolfe, D.M.; Quinn, R.P.; Snoke, J.D.; Rosenthal, R.A. Organizational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Dubinsky, A.B.; Mattson, R.E.; Michaels, M.; Kotabe, C.U.; Lim, H.M. Influence of Role Stress on Industrial Salespeople’s Work Outcomes in the United States, Japan, and Korea. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1992, 23, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.P.; Murrmann, S.K.; Lee, G. Moderating effects of gender and organizational level between role stress and job satisfaction among hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, S.M.; Brief, A.P.; Schuler, R.S. Role conflict and role ambiguity: Integration of the literature and directions for future research. Hum. Relat. 1981, 34, 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.; George, R.T. Understanding the influence of polychronicity on job satisfaction and turnover intention: A study of non-supervisory hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.J.; Lambert, R.G.; Reiser, J. Vocational Concerns of Elementary Teachers: Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Occupational Commitment. J. Employ. Couns. 2014, 51, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgunduz, Y. The influence of self-esteem and role stress on job performance in hotel businesses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1082–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.E. Stress and Behavior in Organizations. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.S., Ed.; Rand McNally College Pub.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, T.; Kilic, C. The Effect of Market Orientation on New Product Performance: The Role of Strategic Capabilities. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2015, 19, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Powpaka, S. How market orientation affects female service employees in Thailand. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, H.L.; Rizzo, J.R.; Carroll, S.J. Management Organizational Behavior; Blackwell Publishers: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, D.; Kim, H.; Crutsinger, C. Examining the effects of role stress on customer orientation and job performance of retail salespeople. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.L.; Lu, L.C.; Su, H.J.; Lin, T.A.; Chang, K.Y. The Mediating Effect of Role Stressors on Market Orientation and Organizational Commitment. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2010, 38, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Boles, J.S. Employee behavior in a service environment: A model and test of potential differences between men and women. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R.L. The social psychology of organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.L.; Morrison, E.W. Psychological contracts and OCB: The effect of unfulfilled obligations on civic behavior. J. Organ. Citizsh. Behav. 1995, 16, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P. Organizational Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dyne, L.V.; Graham, J.G.; Dienesch, R.M. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Construct Redefinition, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 765–802. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D. The motivational basis of organizational behavior. Behav. Sci. 1964, 9, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.W.; Tang, Y.Y. Promoting service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors in hotels: The role of high-performance human resource practices and organizational social climates. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.; Chuang, C. Individual differences, psychological contract breach, and organizational citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation study. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Datta, S.; Blake, B.S.; Bhargava, S. Linking LMX, innovative work behaviour and turnover intentions: The mediating role of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A.; Sharoni, G. Organizational citizenship behavior, organizational justice, job stress, and workfamily conflict: Examination of their interrelationships with respondents from a non-Western culture. Rev. De Psicol. Del Trab. Y De Las Organ. 2014, 30, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.C.; Shiao, S.Y.; Ho, W.C. Relationship among Organizational Support, Knowledge Sharing and Citizenship Behaviors Based on the Perspective of Social Exchange Theory: Viewpoints of Trust and Relationship. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 5, 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.T.; Xinmin, Z.J. Impact of Transformational Leadership’s on Employee Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Examing A Multiple-Mediation Model. Sci. Sci. Manag. 2010, 3, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Yue, A.; Han, Y.; Chen, H. Exploring the Effect of Different Performance Appraisal Purposes on Miners’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organization Identification. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deepa, E.; Palaniswamy, R.; Kuppusamy, S. Effect of performance appraisal system in organizational commitment, job satisfaction and productivity. J. Contemp. Manag. Res 2014, 8, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Redman, T.; Snape, E. The consequences of dual and unilateral commitment to the organisation and union. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamsani, H.; Valeriani, D.; Zukhri, N. Work Status, Satisfaction and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Case Study on Bangka Islamic Bank. Prov. Bangka Belitung Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Colquitt, J.A. Organizational justice and stress: The mediating role of work-family conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moorman, R.H. Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, P.N.; Robert, H.M. Justice as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Methods of Monitoring and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. AMJ 1993, 36, 527–556. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, E.S.; Xin, X.C. Re-examining Citizenship: How the Control of Measurement Artifacts Affects Observed Relationships of Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Organizational Variables. Hum. Perform. 2014, 27, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Leigang, Z.; Huaibin, J.; Tingting, J. Leader-member exchange and organisational citizenship behaviour: The mediating and moderating effects of role ambiguity. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.P.; Christopher, E.; Lin, S.C. Impetus for Action: A Cultural Analysis of Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Chinese Society. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of pls-sem. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H. Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in pls-sem: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3192–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Shiau, W.-L.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Fritze, M.P. Methodological research on partial least squares structural equation modeling (pls-sem): An analysis based on social network approaches. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. Pls path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using pls path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (pls) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. A meta-analysis of cronbach’s coefficient alpha. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Engelen, S. Fast cross-validation of high-breakdown resampling methods for pca. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 51, 5013–5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Taniguchi, M. Discriminant analysis for stationary vector time series. J. Time Ser. Anal. 1994, 15, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, E.A.; Alonso, A.M. Discriminant analysis of multivariate time series: Application to diagnosis based on ecg signals. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2014, 70, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, I.S.; Ragsdale, C.T. Combining neural networks and statistical predictions to solve the classification problem in discriminant analysis. Decis. Sci. 1995, 26, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 128 | 52% |

| Female | 117 | 48% | |

| Age | Less than 24 | 13 | 5% |

| 25–29 | 41 | 17% | |

| 30–39 | 63 | 26% | |

| 40–49 | 50 | 20% | |

| 50–59 | 51 | 21% | |

| Over 60 | 27 | 11% | |

| Marriage | Yes | 156 | 64% |

| No | 89 | 36% | |

| Education | Senior High School | 49 | 20% |

| College | 153 | 62% | |

| Above Graduate School | 43 | 18% | |

| Seniority | Under 1 year | 12 | 5% |

| 1–5 years | 54 | 22% | |

| 6–10 years | 69 | 28% | |

| 10–15 years | 60 | 25% | |

| Over 16 years | 50 | 20% | |

| Area | North Area | 107 | 44% |

| Central Area | 77 | 31% | |

| South Area | 61 | 25% |

| Factor | Item | Loading | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Orientation (CO) | CO1 | 0.89 | 54.26 |

| CO2 | 0.87 | 46.22 | |

| CO3 | 0.89 | 47.49 | |

| CO4 | 0.74 | 20.62 | |

| Competitor Orientation (CPO) | CPO1 | 0.91 | 17.13 |

| CPO2 | 0.90 | 57.93 | |

| CPO3 | 0.89 | 57.49 | |

| CPO4 | 0.77 | 45.25 | |

| Inter-Functional Coordination (IFC) | IFC1 | 0.79 | 20.05 |

| IFC2 | 0.77 | 33.82 | |

| IFC3 | 0.87 | 40.79 | |

| Role Conflict (RC) | RC1 | 0.84 | 29.95 |

| RC2 | 0.91 | 78.85 | |

| RC3 | 0.61 | 8.63 | |

| RC4 | 0.89 | 43.43 | |

| Role Ambiguity (RA) | RA1 | 0.77 | 16.41 |

| RA2 | 0.76 | 26.84 | |

| RA3 | 0.67 | 13.67 | |

| RA4 | 0.67 | 8.61 | |

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) | OCB1 | 0.81 | 28.19 |

| OCB2 | 0.80 | 30.79 | |

| OCB3 | 0.84 | 25.45 | |

| OCB4 | 0.78 | 17.71 |

| Construct | Composite Reliability | Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Orientation | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.87 |

| Competitor Orientation | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.89 |

| Inter-functional Coordination | 0.85 | 0.66 | 0.74 |

| Role Conflict | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| Role Ambiguity | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0.70 |

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.82 |

| Mean | S. D | CO | CPO | IFC | RC | RA | OCB | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Orientation | 6.01 | 0.67 | (0.85) | 0.72 | |||||

| Competitor Orientation | 6.22 | 0.62 | 0.43 | (0.87) | 0.76 | ||||

| Inter-Functional Coordination | 6.14 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.36 | (0.81) | 0.66 | |||

| Role Conflict | 1.90 | 0.58 | −0.50 | −0.51 | −0.77 | (0.82) | 0.67 | ||

| Role Ambiguity | 2.34 | 0.70 | −0.49 | −0.61 | −0.58 | 0.71 | (0.72) | 0.52 | |

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior | 6.29 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.72 | −0.76 | −0.59 | (0.81) | 0.65 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficients | t-Value | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Consumer orientation → Role conflict | −0.146 | 2.644 | 0.008 |

| H2 | Consumer orientation → Role ambiguity | −0.169 | 2.893 | 0.004 |

| H3 | Competitor orientation → Role conflict | −0.220 | 4.200 | 0.000 |

| H4 | Competitor orientation → Role ambiguity | −0.409 | 6.900 | 0.000 |

| H5 | Inter-functional coordination → Role conflict | −0.634 | 14.039 | 0.000 |

| H6 | Inter-functional coordination → Role ambiguity | −0.361 | 6.395 | 0.000 |

| H7 | Role conflict → Organizational citizenship behavior | −0.698 | 11.564 | 0.000 |

| H8 | Role ambiguity → Organizational citizenship behavior | −0.088 | 1.380 | 0.168 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, L.; Chang, K.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-C. How Can Travel Agencies Create Sustainable Competitive Advantages? Perspective on Employee Role Stress and Initiative Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114557

Huang L, Chang K-Y, Yeh Y-C. How Can Travel Agencies Create Sustainable Competitive Advantages? Perspective on Employee Role Stress and Initiative Behavior. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114557

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Leo, Kuang-Yu Chang, and Yu-Chen Yeh. 2020. "How Can Travel Agencies Create Sustainable Competitive Advantages? Perspective on Employee Role Stress and Initiative Behavior" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114557

APA StyleHuang, L., Chang, K.-Y., & Yeh, Y.-C. (2020). How Can Travel Agencies Create Sustainable Competitive Advantages? Perspective on Employee Role Stress and Initiative Behavior. Sustainability, 12(11), 4557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114557