Values Influence Public Acceptability of Geoengineering Technologies Via Self-Identities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Geoengineering Technologies

1.2. Theoretical Framework

1.2.1. Values

1.2.2. Values and Self-Identities

1.2.3. Values, Self-Identities, and Acceptability

1.3. Environmental, Economic, and Political Self-Identities

1.4. Aims of This Paper

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Design

2.2. Materials and Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Zero-Order Correlations

3.2. Geothermal Energy

3.2.1. Zero-Order Correlations

3.2.2. Indirect Relationships

3.3. Nuclear Power

3.3.1. Zero-Order Correlations

3.3.2. Indirect Relationships

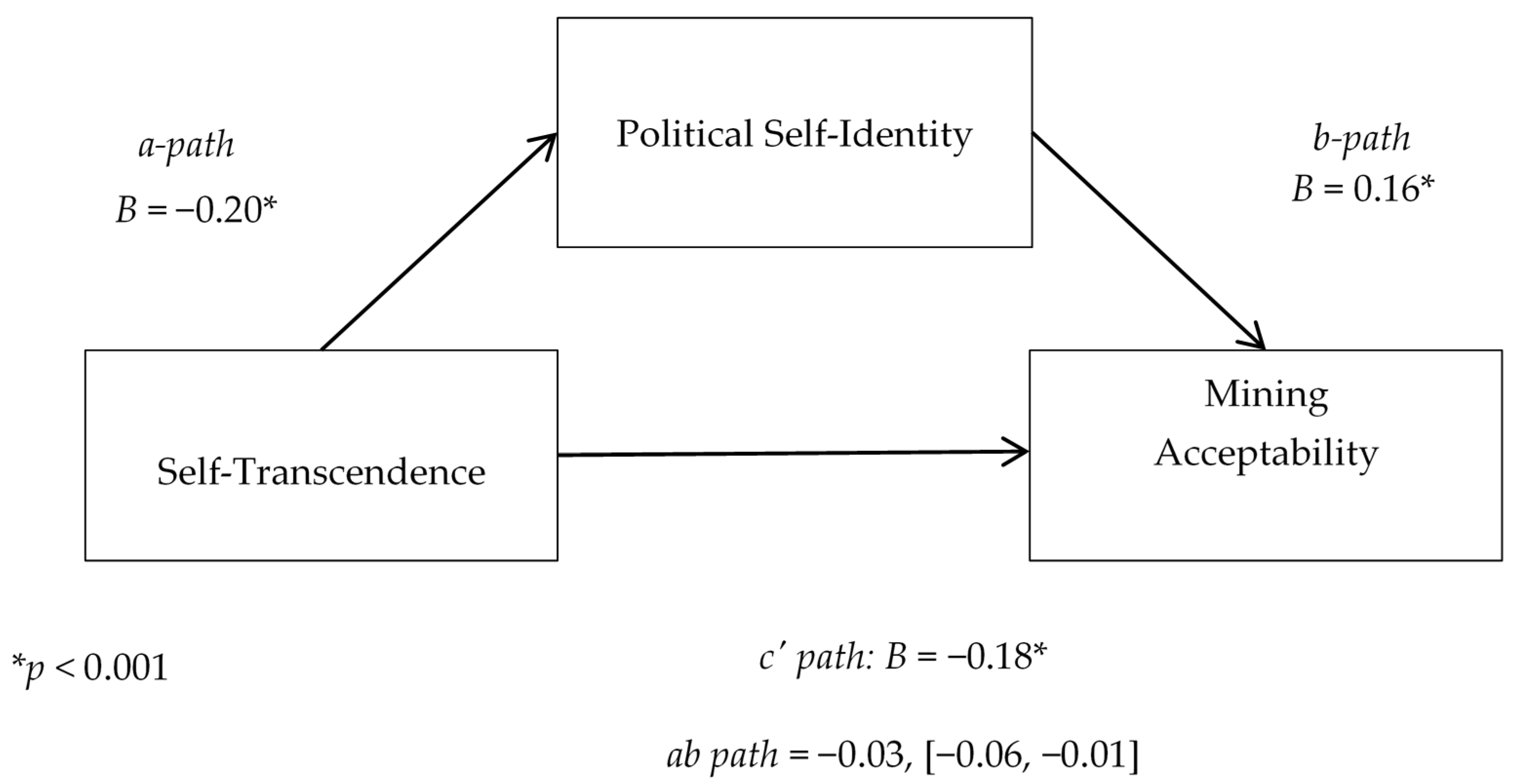

3.4. Mining

3.4.1. Zero-Order Correlations

3.4.2. Indirect Relationships

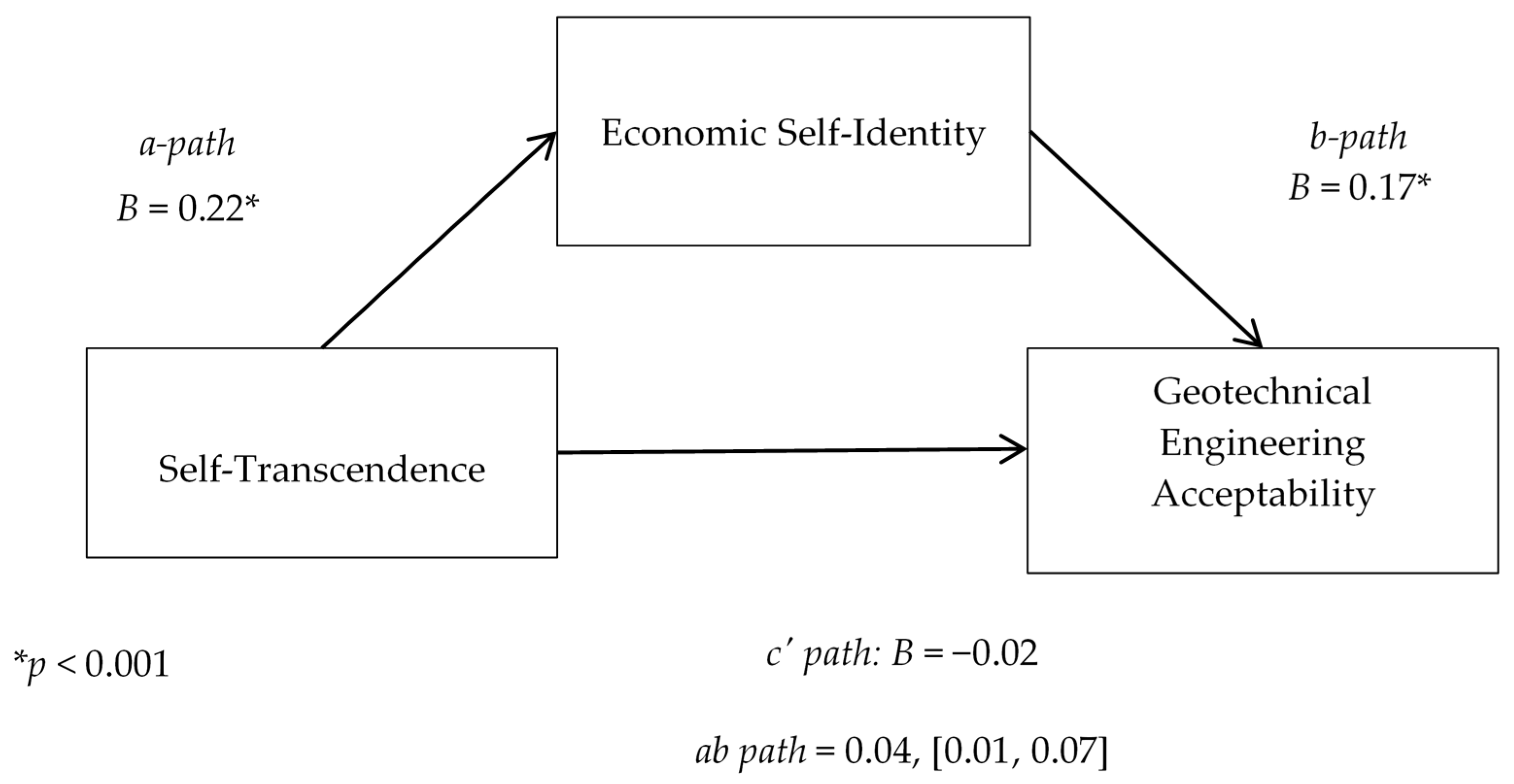

3.5. Geotechnical Engineering

3.5.1. Zero-Order Correlations

3.5.2. Indirect Relationships

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- About the Sustainable Development of Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Dowd, A.M.; Boughen, N.; Ashworth, P.; Carr-Cornish, S. Geothermal energy in Australia: Investigating social acceptance. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 6301–6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Stern, P.C.; Whitmarsh, L.; Carrico, A.; Steg, L.; Bonnes, M. Psychological research and global climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlaviciute, G.; Schuitema, G.; Devine-Wright, P.; Ram, B. At the heart of a sustainable energy transition: The public acceptability of energy projects. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2018, 16, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prno, J.; Slocombe, D.S. Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’ in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Energy studies need social science. Nat. News 2014, 511, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. What are we doing here? Analyzing fifteen years of energy scholarship and proposing a social science research agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Saleem, H.A.; Bazilian, M.; Radley, B.; Numery, B.; Okatz, J.; Mulvaney, D. Sustainable minerals and metals for a low-carbon future. Science 2020, 367, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geological Survey of Ireland. Review of key issues around social acceptance of geoscience activities earth resources in Ireland. In Research Conducted by SLR Consulting, GSI PROC 24/2015; Geological Survey of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, I.S.; Ickert, J.; Lacassin, R. Communicating seismic risk: The geoethical challenges of a people-centred, participatory approach. Ann. Geophys. 2017, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Van der Werff, E. Understanding the human dimensions of a sustainable energy transition. Front. Psychol 2015, 6, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schuitema, G.; Ryan, L.; Aravena, C. The consumer’s role in flexible energy system: An interdisciplinary approach to changing consumers’ behavior. IEEE P E Mag. 2017, 15, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W.; Purdam, K.; Darnton, A.; McLachlan, C.; Devine-Wright, P. Public Attitudes to Environmental Change: A Selective Review of Theory and Practice: A Research Synthesis for the Living with Environmental Change Programme; Research Councils: Swindon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Upham, P.; Poortinga, W.; Darnton, A.; McLachlan, C.; Devine-Wright, P. Sherry-Brennan Public Attitudes, Understanding, and Engagement in Relation to Low-carbon Energy: A Selective Review of Academic and Non-Academic Literatures; Research Councils UK Energy Programme: Swindon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L.; Poortinga, W. Values, perceived risks and benefits, and acceptability of nuclear energy. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.R.; Yardley, S.; Medley, S. The social acceptance of fusion: Critically examining public perceptions of uranium-based fuel storage for nuclear fusion in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 52, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benighaus, C.; Bleicher, A. Neither risky technology nor renewable electricity: Contested frames in the development of geothermal energy in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 47, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffacher, M.; Muggli, N.; Scolobig, A.; Moser, C. Framing deep geothermal energy in mass media: The case of Switzerland. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 98, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Sütterlin, B. Human and nature-caused hazards: The affect heuristic causes biased decisions. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, R. Green energy futures: Responsible mining on Minnesota’s Iron Range. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Graetz, G. Energy for whom? Uranium mining, Indigenous people, and navigating risk and rights in Australia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černoch, F.; Lehotský, L.; Ocelík, P.; Osička, J.; Vencourová, Z. Anti-fossil frames: Examining narratives of the opposition to brown coal mining in the Czech Republic. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 54, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotey, B.; Rolfe, J. Demographic and economic impact of mining on remote communities in Australia. Resour. Policy 2014, 42, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.M.; Paxton, G.; Parsons, R.; Parr, J.M.; Moffat, K. For the benefit of Australians”: Exploring national expectations of the mining industry. Resour. Policy 2014, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Pert, P.; McCrea, R.; Boughen, N.; Rodriguez, M.; Lacey, J. Australian Attitudes toward Mining: Citizen Survey—2017 Results; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2017.

- Moffat, K.; Zhang, A.; Boughen, N. Australian Attitudes toward Mining: Citizen Survey—2014 Results; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Devine-Wright, P. Beyond NIMBYism: Towards an integrated framework for understanding public perceptions of wind energy. Wind Energy 2005, 8, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Oltra, C.; Boso, À. Towards a cross-paradigmatic framework of the social acceptance of energy systems. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.J.; Kerr, G.N.; Moore, K. Attitudes and intentions towards purchasing GM food. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, S. Values as the core of personal identity: Drawing links between two theories of self. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2003, 66, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. I am what I am by looking past the present: The influence of biospheric values and past behavior on environmental self-identity. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 626–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse proenvironmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N.T. Values, valences, and choice: The influences of values on the perceived attractiveness and choice of alternatives. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Shwom, R.; Dietz, T. What drives energy consumers? Engaging people in a sustainable energy transition. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2018, 16, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, S.C.; Rosa, E.A.; Dan, A.; Dietz, T. The future of nuclear power: Value orientations and risk perception. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colvin, R.M.; Witt, G.B.; Lacey, J. Strange bedfellows or an aligning of values? Exploration of stakeholder values in an alliance of concerned citizens against coal seam gas mining. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, R.M.; Witt, G.B.; Lacey, J. The social identity approach to understanding socio-political conflict in environmental and natural resources management. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 34, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. The influence of values on evaluations of energy alternatives. Renew. Energy 2015, 77, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.S.; Lewis, D. Communicating contested geoscience to the public: Moving from ‘matters of fact’ to ‘matters of concern’. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 174, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Nash, N.; Upham, P.; Lloyd, A.; Verdon, J.P.; Kendall, J.M. UK public perceptions of shale gas hydraulic fracturing: The role of audience, message and contextual factors on risk perceptions and policy support. Appl. Energy 2015, 160, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Boehnke, K. Evaluating the structure of human values with confirmatory factor analysis. J. Res. Personal. 2004, 38, 230–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value structures behind proenvironmental behaviour. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, S0272–S4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value priorities and behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value systems. In The Psychology of Values: The Ontario Symposium; Seligman, C., Olson, J.M., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1996; Volume 8, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, environmental concern, and environmental behavior: A study into household energy use. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. Follow the signal: When past pro-environmental actions signal who you are. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gecas, V. Value identities, self-motives, and social movements. In Self, Identity, and Social Movements; Stryker, S., Owens, T.J., White, R.W., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, T.; Kasser, T. Meeting Environmental Challenges: The Role of Human Identity; WWF-UK: Godalming, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R. Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior: Assessing the role of identification with “green consumerism”. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Holland, R.W. Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheek, J.M. Identity orientations and self-interpretation. In Personality Psychology; Buss, D.M., Cantor, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, R.J. The importance of authenticity for self and society. Symb. Interact. 1985, 18, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Toner, K.; Gan, M. Self, identity, and reactions to distal threats: The case of environmental behavior. Psychol. Stud. 2011, 56, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitema, G.; Anable, J.; Skippon, S.; Kinnear, N. The role of instrumental, hedonic, and symbolic attributes in the intention to adopt electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A 2013, 48, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; McDonald, R.; Louis, W.R. Theory of planned behaviour, identity, and intentions to engage in environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Opotow, S. Introduction: Identity and the natural environment. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; Clayton, S., Opotow, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nestle, U. Does the use of nuclear power lead to lower electricity prices? An analysis of the debate in Germany with an international perspective. Energy Policy 2012, 41, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, T.C.; Fleischmann, K.R. The relationship between human values and attitudes toward the Park51 and nuclear power controversies. Proc. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, G.; Pandelaere, M.; Warlop, L.; Dewitte, S. Positive cueing: Promoting sustainable consumer behavior by cueing common environmental behaviors as environmental. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2008, 25, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. It is a moral issue: The relationship between environmental self-identity, obligation-based intrinsic motivation and pro-environmental behavior. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. The psychology of participation and interest in smart-energy systems: Comparing the value-belief-norm theory and the value-identity-personal norm model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 20, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gatersleben, B.; Murtagh, N.; Abrahamse, W. Values, identity, and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2014, 9, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boudet, H.; Clarke, C.; Bugden, D.; Maibach, E.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Leiserowitz, A. “Fracking” controversy and communication: Using national survey data to understand public perceptions of hydraulic fracturing. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Juknys, R. The role of values, environmental risk perception, awareness of consequences, and willingness to assume responsibility for environmentally-friendly behaviour: The Lithuanian case. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3413–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indecon. An Economic Review of the Irish Geoscience Sector; Indecon International Economic Consultants: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, D. The economic impact of Marcellus shale gas drilling: What have we learned? What are the limitations? In Working Paper Series: A Comprehensive Economic Analysis of Natural Gas Extraction in the Marcellus Shale; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Science Foundation Ireland. Science Foundation Ireland—Science in Ireland Barometer: An Analysis of the Irish Public’s Perceptions and Awareness of STEM in Society; Science Foundation Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environ. Behav. 2007, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors, and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hurst, M.; Dittmar, H.; Bond, R.; Kasser, T. The relationship between materialistic values and environmental attitudes and behaviours: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Van der Werff, E. The significance of hedonic values for environmentally relevant attitudes, preferences, and actions. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D. Political distinctiveness: An identity optimising approach. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 24, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duck, J.M.; Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.J. Me, us, and them: Political identification and the third-person effect in the 1993 Australian federal election. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duck, J.M.; Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A. Perceptions of a media campaign: The role of social identity and the changing intergroup context. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Xiao, C.; McCright, A.M. Political and environment in America: Partisan and ideological cleavages in public support for environmentalism. Environ. Politics 2011, 10, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.A.; Willer, R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCright, A.M.; Dunlap, R.E. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 21, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.R.; Schuldt, J.P.; Romero-Canyas, R. Social climate science: A new vista for psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Fielding, K.S. It’s political: How the salience of one’s political identity changes climate change beliefs and policy support. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 27, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Font, J.; Rudisill, C.; Mossialos, E. Attitudes as an expression of knowledge and “political anchoring”: The case of nuclear power in the United Kingdom. Risk Anal. 2008, 28, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffarth, M.R.; Hodson, G. Green on the outside, red on the inside: Perceived environmentalist threat as a factor explaining political polarization of climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, M.F.; Schwartz, S. Values and voting. Political Psychol. 1998, 19, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burningham, K.; Barnett, J.; Thrush, D. The Limitations of the NIMBY Concept for Understanding Public Engagement with Renewable energy Technologies: A Literature Review; Working Paper; School of Environment and Development, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Contextual and psychological factors shaping evaluations and acceptability of energy alternatives: Integrated review and research agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations. In Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally—Lessons from the European Social Survey; Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R., Eva, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 169–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward a theory of the universal content and structure of values: Extensions and cross-cultural replications. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunally, J.O. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, S.R.; Cheek, J.M. The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J. Personal. 1986, 54, 106–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, E.; Schmidt, P.; Schwartz, S.H. Bringing values back in: The adequacy of the European Social Survey to measure values in 20 countries. Public Opinion Q. 2008, 72, 420–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Melech, G.; Lehmann, A.; Burgess, S.; Harris, M.; Owens, V. Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2001, 32, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, W.A.P.; Igou, E.R. Going to political extremes in response to boredom. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J.W. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, C.; Hertel, M. Contested deep geothermal energy in Germany—The emergence of an environmental protest movement. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 27, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Dessai, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Morton, T.A.; Pidgeon, N.F. Psychological responses to the proximity of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, P.; Stirling, A. Comparing nuclear trajectories in Germany and the United Kingdom: From regimes to democracies in sociotechnical transitions and discontinuities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 59, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleeming, R.G. Factors affecting attitudes toward nuclear power in the Netherlands. The J. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 125, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Gilbert, A.; Nugent, D. An international comparative assessment of construction cost overruns for electricity infrastructure. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.; Schweizer-Ries, P.; Wemheuer, C. Public acceptance of renewable energies: Results from case studies in Germany. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4136–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I.M.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W.; Siero, F. General antecedents of personal norms, policy acceptability, and intentions: The role of values, worldviews, and environmental concern. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Fitzgerald, A.; Shwom, R. Environmental values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 335–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I.M. Environmental values. In The Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Trafimow, D.; Khusid, I.K.; Holland, R.W.; Steentjes, G.M. Different selves, different values: Effects of self-construals on value activation and use. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, W. Brazil: Mining 2020; Advogados: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Goal-framing theory and norm-guided environmental behaviour. In Encouraging Sustainable Behaviour; Van Trijp, H., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine-Wright, P. Reconsidering Public Attitudes and Public Acceptance of Renewable Energy Technologies: A Critical Review; Working Paper; School of Environment and Development, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schuitema, G.; Steg, L.; Forward, S. Explaining differences in acceptability before and acceptance after the implementation of a congestion charge in Stockholm. Transp. Res. Part A Pol. Prac. 2010, 44, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Zani, B. The effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident on risk perception, antinuclear behavioral intentions, attitude, trust, environmental beliefs, and values. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.C. Opening the black box of psychological processes in the science of a sustainable future: A new frontier. Europ. Jour. Sus. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Descriptive Statistics | N | M | SD | Max | Min | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ||||||

| Openness to Change | 505 | 3.93 | 0.78 | 6.00 | 1.83 | 0.73 |

| Conservatism | 505 | 3.76 | 0.83 | 5.83 | 1.33 | 0.69 |

| Self-Transcendence | 505 | 4.82 | 0.70 | 6.00 | 2.40 | 0.71 |

| Self-Enhancement | 505 | 3.29 | 0.91 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 |

| Environmental Self-Identity | 505 | 5.82 | 1.01 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Economic Self-Identity | 505 | 5.28 | 1.05 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 0.88 |

| Political Self-Identity | 505 | 3.46 | 1.28 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 0.78 |

| Geothermal Acceptability | 505 | 5.77 | 1.19 | 7.00 | 1.00 | - |

| Nuclear Acceptability | 505 | 3.82 | 1.96 | 7.00 | 1.00 | - |

| Mining Acceptability | 505 | 4.49 | 1.45 | 7.00 | 1.00 | - |

| Geotechnical Acceptability | 505 | 5.55 | 1.15 | 7.00 | 1.00 | - |

| Open | Conser | Self-Trans | Self-Enhance | Env | Econ | Pol | GthA | NucA | MinA | GtechA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open | - | 0.11 * | 0.36 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.11 * | 0.12 ** | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 * |

| Conser | - | - | 0.17 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.07 | 0.33 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.12 ** | 0.00 |

| Self-Trans | - | - | - | 0.09 * | 0.52 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.11 * | −0.09 * | −0.22 ** | 0.02 |

| Self-Enhance | - | - | - | - | −0.004 | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.09 * | 0.10 * | 0.06 |

| Env | - | - | - | - | - | 0.43 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.12 ** | −0.04 | −0.20 ** | −0.01 |

| Econ | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.13 ** | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.16 ** |

| Pol | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.03 | 0.10 * | 0.19 ** | 0.02 |

| GthA | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.33 ** |

| NucA | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.26 ** | 0.16 ** |

| MinA | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.22 ** |

| Predictors | Mediators | Path a | Path b | ab | 95% CI of ab | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatism | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.07 | 0.12 * | 0.01 | [−0.003, 0.02] | 2.15 |

| Openness to Change | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.26 ** | 0.09 * | 0.02 | [0.0001, 0.05] | 2.16 |

| Self-Transcendence | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.52 ** | 0.08 | 0.04 | [−0.01, 0.10] | 1.75 |

| Self-Enhancement | Environmental Self-Identity | −0.004 | 0.12 * | −0.001 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 1.52 |

| Conservatism | Economic Self-Identity | 0.33 ** | 0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | 0.85 |

| Openness to Change | Economic Self-Identity | 0.19 ** | −0.01 | −0.001 | [−0.02, 0.02] | 1.33 |

| Self-Transcendence | Economic Self-Identity | 0.22 ** | −0.01 | −0.002 | [−0.02, 0.02] | 1.28 |

| Self-Enhancement | Economic Self-Identity | 0.16 ** | 0.01 | 0.002 | [−0.01, 0.02] | 0.16 |

| Conservatism | Political Self-Identity | 0.39 ** | 0.002 | 0.001 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.64 |

| Openness to Change | Political Self-Identity | −0.11 * | −0.02 | 0.002 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 1.36 |

| Self-Transcendence | Political Self-Identity | −0.20 ** | −0.01 | 0.001 | [−0.02, 0.02] | 1.28 |

| Self-Enhancement | Political Self-Identity | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.002 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.24 |

| Predictors | Mediators | Path a | Path b | ab | 95% CI of ab | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatism | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.003 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.20 |

| Openness to Change | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.26 ** | −0.06 | −0.01 | [−0.04, 0.01] | 0.49 |

| Self-Transcendence | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.52 ** | 0.01 | 0.004 | [−0.05, 0.06] | 0.77 |

| Self-Enhancement | Environmental Self-Identity | −0.004 | −0.04 | 0.0002 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.96 |

| Conservatism | Economic Self-Identity | 0.33 ** | 0.07 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.50 |

| Openness to Change | Economic Self-Identity | 0.19 ** | 0.06 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 0.61 |

| Self-Transcendence | Economic Self-Identity | 0.22 ** | 0.09 * | 0.02 | [0.001, 0.05] | 1.61 |

| Self-Enhancement | Economic Self-Identity | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 1.14 |

| Conservatism | Political Self-Identity | 0.39 ** | 0.11 * | 0.04 | [0.01, 0.08] | 1.13 |

| Openness to Change | Political Self-Identity | −0.11 * | 0.11 * | −0.01 | [−0.03, −0.001] | 1.41 |

| Self-Transcendence | Political Self-Identity | −0.20 ** | 0.09 * | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.001] | 1.53 |

| Self-Enhancement | Political Self-Identity | 0.06 | 0.10 * | 0.01 | [−0.003, 0.02] | 1.78 |

| Predictors | Mediators | Path a | Path b | ab | 95% CI of ab | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatism | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.07 | −0.21 ** | −0.01 | [−0.04, 0.01] | 5.80 |

| Openness to Change | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.26 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.06 | [−0.09, −0.03] | 4.38 |

| Self-Transcendence | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.52 ** | −0.12 * | −0.06 | [−0.12, −0.01] | 5.68 |

| Self-Enhancement | Environmental Self-Identity | −0.004 | −0.20 ** | 0.001 | [−0.02, 0.02] | 5.00 |

| Conservatism | Economic Self-Identity | 0.33 ** | 0.04 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | 1.61 |

| Openness to Change | Economic Self-Identity | 0.19 ** | 0.07 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.55 |

| Self-Transcendence | Economic Self-Identity | 0.22 ** | 0.13 * | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.05] | 6.18 |

| Self-Enhancement | Economic Self-Identity | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 1.39 |

| Conservatism | Political Self-Identity | 0.39 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.07 | [0.03, 0.11] | 3.94 |

| Openness to Change | Political Self-Identity | −0.11 * | 0.20 ** | −0.02 | [−0.04, −0.01] | 3.79 |

| Self-Transcendence | Political Self-Identity | −0.20 ** | 0.16 ** | −0.03 | [−0.06, −0.01] | 6.94 |

| Self-Enhancement | Political Self-Identity | 0.06 | 0.19 ** | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 4.52 |

| Predictors | Mediators | Path a | Path b | ab | 95% CI of ab | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatism | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.0004 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.00 |

| Openness to Change | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.26 ** | −0.03 | −0.01 | [−0.03, 0.02] | 0.97 |

| Self-Transcendence | Environmental Self-Identity | 0.52 ** | −0.02 | −0.01 | [−0.07, 0.05] | 0.09 |

| Self-Enhancement | Environmental Self-Identity | −0.004 | −0.01 | 0.0001 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.34 |

| Conservatism | Economic Self-Identity | 0.33 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.06 | [0.03, 0.10] | 3.02 |

| Openness to Change | Economic Self-Identity | 0.19 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.06] | 3.10 |

| Self-Transcendence | Economic Self-Identity | 0.22 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.04 | [0.01, 0.07] | 2.72 |

| Self-Enhancement | Economic Self-Identity | 0.16 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.05] | 2.81 |

| Conservatism | Political Self-Identity | 0.39 ** | 0.02 | 0.01 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.03 |

| Openness to Change | Political Self-Identity | −0.11 * | 0.03 | −0.003 | [−0.02, 0.01] | 0.96 |

| Self-Transcendence | Political Self-Identity | −0.20 ** | 0.02 | −0.01 | [−0.03, 0.01] | 0.09 |

| Self-Enhancement | Political Self-Identity | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.001 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.35 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moynihan, A.B.; Schuitema, G. Values Influence Public Acceptability of Geoengineering Technologies Via Self-Identities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114591

Moynihan AB, Schuitema G. Values Influence Public Acceptability of Geoengineering Technologies Via Self-Identities. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114591

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoynihan, Andrew B., and Geertje Schuitema. 2020. "Values Influence Public Acceptability of Geoengineering Technologies Via Self-Identities" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114591

APA StyleMoynihan, A. B., & Schuitema, G. (2020). Values Influence Public Acceptability of Geoengineering Technologies Via Self-Identities. Sustainability, 12(11), 4591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114591