New Opportunities for Cruise Tourism: The Case of Italian Historic Towns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Trends and Characteristics of the Cruise Industry

3.2. The Shore Excursions of the Main Cruise Lines in Italy

- Panoramic: A type of shore excursions aimed at showing the different features of a city with no specific focus and where the cultural aspect is not a priority. Offered in all 11 ports.

- Culinary: Implies the tasting of typical Italian products (pasta, cheeses, wines, liquors), sometimes with the direct involvement of tourists in the practical making of the products. Offered in all 11 ports.

- Active: Cultural and/or sport activities where passengers are involved in hiking and cycling tours in natural environments and historical centres. Offered in all 11 ports.

- Cultural: Traditional cultural visits to monuments, archaeological sites, museums, churches/sanctuaries, etc. Offered in 10 out of 11 ports (except for Genoa).

- Cultural/panoramic: Coach tours with short stops aimed at providing an overview of the main points of interest. Offered in 8 out of 11 ports (except for Bari, Palermo, and Savona).

- Panoramic/active: These excursions offer overviews of the main points of interest, but unlike the previous case, they entail the use of particular means of transport such as jeeps, gondolas, and ferries. Offered in 8 out if 11 ports (except for Bari, Palermo, and Savona).

- Shopping: These mainly consist of trips to shopping malls and outlets and they are not explicitly linked to the purchase of local products. Only offered in 5 ports (Civitavecchia, La Spezia, Naples, Savona, and Venice).

3.3. Pressure Distribution Strategies: The Case of Italian Villages

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- Terminal managers

- Ship lines

- Local administrators

- Port authorities

- Tourists

- Local population

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA). State of the Cruise 2020, Industry Outlook. Available online: https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/state-of-the-cruise-industry.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Capacci, A. El mercado de cruceros en el mediterráneo. Pap. Tur. 2000, 1, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mangano, S. Il turismo croceristico: Il caso di Genova. Ann. Ric. Studi Geogr. 2000, 2, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ridolfi, G.; Soriani, S. Il Mediterraneo delle crociere. In L’Articolazione Territoriale Dello Spazio Costiero. Il Caso Dell’Alto Adriatico; Soriani, S., Ed.; Libreria Editrice Cafoscariana: Venezia, Italy, 2000; pp. 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cesare, F. Il turismo crocieristico. In Diciottesimo Rapporto sul Turismo Italiano 2011–12; Mercury: Firenze, Italy, 2013; pp. 487–500. [Google Scholar]

- Babinger, F. Impacto de los cruceros en la economía local y regional: El caso de Progreso, Yucatán, México. In Temas Pendientes y Nuevas Oportunidades en Turismo y Cooperación al Desarrollo; Nel-lo Andreu, M., Campos Cámara, B.L., Sosa Ferreira, A.P., Eds.; Universitat Rovira I Virgili: Tarragona, Spain, 2015; pp. 268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Wondirad, A. Retracing the past, comprehending the present and contemplating the future of cruise tourism through a meta-analysis of journal publications. Mar. Policy 2019, 108, 103618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H.; Law, R. In search of ‘a research front’ in cruise tourism studies. Inter. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Petrick, J.F.; Papathanassis, A.; Li, X. A meta-analysis of the direct economic impacts of cruise tourism on port communities. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, L.J.; Butler, R.W. Cruise ship industry-patterns in the Caribbean 1880–1986. Tour. Manag. 1987, 8, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, S.; Choi, H.S.C. Motivational Considerations of the New Generations of Cruising. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Luna Buades, M. El turismo de cruceros en el Mediterráneo y en las Illes Balears. Scr. Nova. Rev. Electr. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2015, 29, 1–33. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-514.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Hung, K.; Petrick, J.F. Why do you cruise? Exploring the motivations for taking cruise holidays, and the construction of a cruising motivation scale. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Hein, C.; Zhang, T. Understanding how Amsterdam City tourism marketing addresses cruise tourists’ motivations regarding culture. Tour. Manag. Persp. 2019, 29, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, F.; Satta, G.; Penco, L.; Persico, L. Destination satisfaction and cruiser behaviour: The moderating effect of excursion package. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.Á.; Del Chiappa, G.; Battino, S. Percepción de los residentes de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria ante el turismo de cruceros. Vegueta. Anu. Fac. Geogr. Hist. 2015, 15, 287–316. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. Inter. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Lorenzo-Romero, C.; Gallarza, M. Host community perceptions of cruise tourism in a homeport: A cluster analysis. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J.K.; Iversen, N.M.; Hem, L.E. Hotspot crowding and over-tourism: Antecedents of destination attractiveness. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Schlesinger, W. The sustainability of cruise tourism onshore: The impact of crowding on visitors’ satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Cruise Tourists’ Perception of a Port of Call: Differences between Internet Versus Other Information Sources Used. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ff29/1e731c7b4378239741e4cb3c84711bc62427.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Penco, L. Il Business Crocieristico: Imprese, Strategie e Territorio; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- González-Relaño, R.; Mangano, S.; Ugolini, G.M. El territorio como producto turìstico para los cruceristas: El caso de Italia. In Proceedings of the CRAFERIC 2017, II Cruise & Ferries International Conference Cruising Sea Hotels, Madrid, Spain, 22–24 February 2017; Fundacion General de UPM: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Biehn, N. A cruise ship is not a floating hotel. J. Rev. Pricing Manag. 2006, 5, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakson, R. Beyond the tourist bubble? Cruise ship passengers in port. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, L.K.; Miller, A.; Gende, S. Sustainable Cruise Tourism in Marine World Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2020, 12, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, S. Tourism pressures and depopulation in Cannaregio: Effects of mass tourism on Venetian cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, D.; Camatti, N.; Giove, S.; Van der Borg, J. Venice and Overtourism: Simulating Sustainable Development Scenarios through a Tourism Carrying Capacity Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M. La Gran Ola del Turismo en Cádiz: Cómo se Para un Tsunami. Available online: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/cadiz/turistizacion-aumento-precios-alquiler-cruceros (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Boira, J. Turismo y Ciudad. Reflexiones en Torno a Valencia; Universitat de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, N. A Social Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Vehicle Restriction Policy for Reducing Overtourism in Udo, Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Cruise Tourism Development Strategies. 2016. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284417292 (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Asero, V.; Skonieczny, S. Cruise Tourism and Sustainability in the Mediterranean. Destination Venice. In Mobilities, Tourism and Travel Behavior; Butowski, L., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Magano, S. I Territori Culturali in Italia. Geografia e Valorizzazione Turistica; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, M.T.; Cavallo, L. I borghi italiani: Dimensioni e caratteristiche dei flussi turistici. In XXI Rapporto Sul Turismo Italiano; Becheri, E., Micera, R., Morvillo, F., Eds.; Rigosi: Napoli, Italy, 2017; pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.; Radicchi, E.; Zagnoli, P. Port’s Role as a Determinant of Cruise Destination Socio-Economic Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Kwortnik, R.; Gauri, D.K. Exploring behavioural differences between new and repeat cruisers to a cruise brand. Inter. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ruiz, S.; Casado-Díaz, A.B.; Ivars-Baidal, J. Cruise tourism: The role of shore excursions in the overcrowding of cities. Inter. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 6, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, L.; Russo, A.P. Cruise ports: A strategic nexus between regions and global lines-evidence from the Mediterranean. Marit. Pol. Manag. 2011, 38, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Pulina, M.; Riaño, E.; Zapata-Aguirre, S. Cruise Passengers in a Homeport: A Market Analysis. Tour. Geograph. 2013, 15, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cantis, S.; Ferrante, M.; Kahani, A.; Shoval, N. Cruise passengers behaviour at the destination: Investigation using GPS technology. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.; Wolff, K.; Marnburg, E.; Øgaard, T. Belly full, purse closed: Cruise live passengers’ expenditure. Tour. Manag. Perspec. 2013, 6, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, S. Il Piano Strategico per il Turismo 2017–2022 e il programma attuativo 2017–2018. In XXI Rapporto Sul Turismo Italiano; Becheri, E., Micera, R., Morvillo, F., Eds.; Rigosi: Napoli, Italy, 2017; pp. 789–795. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Crociere. Available online: https://www.costacrociere.it/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Royal Caribbean. Available online: https://www.royalcaribbean.com/ita/it?country=ITA (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- MSC Crociere. Available online: https://www.msccrociere.it/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Bandiere arancioni. Available online: https://www.bandierearancioni.it/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- I Borghi Più Belli d’Italia. Available online: https://borghipiubelliditalia.it/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- GP Wild. Cruise Industry Statistical Review 2015–16. 2016. Available online: http://gpwild.britweb-forms.co.uk/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Risposte turismo. Il Traffico Crocieristico in Italia Nel 2017 e le Previsioni Per Il 2018. 2018. Available online: http://www.risposteturismo.it/Public/RisposteTurismo(2018)_SpecialeCrociere.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Risposte turismo. Il Traffico Crocieristico in Italia Nel 2018 e le Previsioni Per il 2019. 2020. Available online: http://www.risposteturismo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/RisposteTurismo2019_SpecialeCrociere2019.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Babinger, F. La actividad crucerística para el desarrollo socioterritorial de destinos turísticos españoles. In Transportes, Movilidad y Nuevas Estrategias Regionales en un Mundo Postcrisis; Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles y Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2018; pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve-Pérez, J.; García-Sánchez, A.; Gutiérrez Romero, J.E. Estacionalidad del turismo de cruceros: El Mediterráneo español. In Actas del XVIII Congreso AECIT; 2014; Available online: https://aecit.org/files/congress/18/papers/107.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Della Corte, V. Imprese e Sistemi Turistici; Egea spa: Milano, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Touring Club Italiano. Bandiere Arancioni Funzionamento e Modalità di Candidatura. 2016. Available online: https://www.bandierearancioni.it/sites/default/files/iniziativa/documenti/brochure%20BA_verticale_18x25,4%20cm_DIGITALE_BASSA_0.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Pencarelli, T.; Fraboni, C.; Splendiani, S. Il ruolo della Bandiera arancione per la valorizzazione dei piccoli comuni dell’entroterra. Il Cap. Cult. Ital. Stud. Value Cult. Herit. 2016, 13, 391–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendiani, S. Le certificazioni ambientali e di qualità delle destinazioni turistiche: Il panorama italiano. In Comunicare le Destinazioni Balneari. Il Ruolo Delle Bandiere Blu in Italia; Pencarelli, T., Ed.; FranAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2015; pp. 49–99. [Google Scholar]

- Il Club dei Borghi. Available online: http://borghipiubelliditalia.it/club/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e per il Turismo. Anno dei Borghi. 2017. Available online: https://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/sito-MiBAC/Contenuti/visualizza_asset.html_664421166.html (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Costa Crociere. Andar per Borghi. 2017. Available online: https://www.costacrociere.it/costa-club/magazine/viaggio/andar-per-borghi.html (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Corriere dell’Umbria. Borghi Più Belli D’Italia, Il Web Sceglie Orvieto. 2016. Available online: https://corrieredellumbria.corr.it/news/attualita/218600/Borghi-piu-belli-d-Italia-.html (accessed on 15 March 2020).

| Region | Municipalities with Villages Which Have Obtained a Quality Certification |

|---|---|

| Campania | Atrani; Cerreto Sannita; Conca dei Marini; Furore; Montesarchio; Nusco; Sant’Agata de’ Goti; Vietri sul Mare |

| Lazio | Acquapendente; Bagnoregio; Bolsena; Bomarzo; Calcata; Caprarola; Castel Gandolfo; Magliano Sabina; Nemi; Sutri; Trevignano Romano; Tuscania; Vitorchiano |

| Liguria | Airole; Ameglia; Apricale; Borgio Verezzi; Brugnato; Campo Ligure; Castelbianco; Castelnuovo Magra; Castelvecchio di Rocca Barbena; Cervo; Finale Ligure; Framura; Laigueglia; Lerici; Millesimo; Moneglia; Noli; Pignone; Sassello; Seborga; Toirano; Varese Ligure; Vernazza; Zuccarello |

| Apulia | Alberobello; Cisternino; Locorotondo |

| Sardinia | Carloforte; Laconi; Sardara |

| Sicily | Castelmola; Castiglione di Sicilia; Castroreale; Cefalù; Erice; Montalbano Elicona; Novara di Sicilia; Petralia Soprana; Petralia Sottana; Salemi; Sambuca di Sicilia; San Marco d’Alunzio; Savoca |

| Toscana | Barberino Val d’Elsa; Barga; Casale Marittimo; Castelnuovo di Val di Cecina; Certaldo; Coreglia Antelminelli; Fosdinovo; Isola del Giglio; Manciano; Massa Marittima; Monte Argentario; Montecarlo; Montescudaio; Peccioli; Pescia; Pitigliano; Pomarance; San Gimignano; Sorano; Suvereto; Vinci; Volterra |

| Veneto | Arquà Petrarca; Asolo; Cison di Valmarino; Follina; Marostica; Mel; Montagnana; Portobuffolè; Soave; Valeggio sul Mincio |

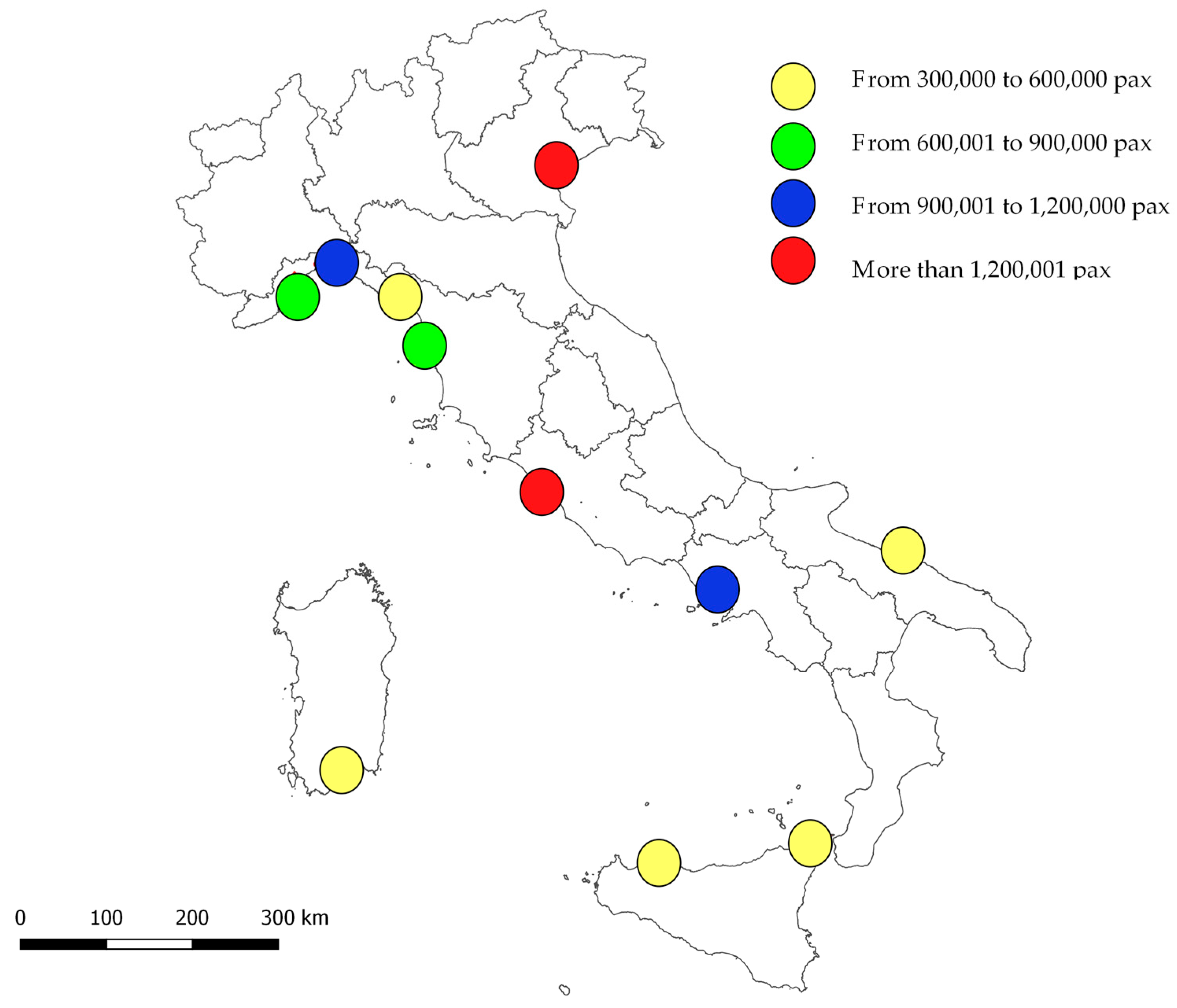

| Ports | Handled Passengers | Calls | Average Value by Call | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.v. | % | a.v. | % | ||

| Civitavecchia | 2,441,737 | 22.0 | 760 | 16.3 | 3213 |

| Venice | 1,560,579 | 14.0 | 502 | 10.8 | 3109 |

| Naples | 1,068,797 | 9.6 | 379 | 8.1 | 2820 |

| Genoa | 1,011,398 | 9.1 | 229 | 4.9 | 4417 |

| Savona | 848,487 | 7.6 | 195 | 4.2 | 4351 |

| Livorno | 786,136 | 7.1 | 354 | 7.6 | 2221 |

| Palermo | 577,934 | 5.2 | 172 | 3.7 | 3360 |

| Bari | 572,906 | 5.2 | 213 | 4.6 | 2690 |

| La Spezia | 448,204 | 4.0 | 129 | 2.8 | 3474 |

| Cagliari | 394,697 | 3.6 | 143 | 3.1 | 2760 |

| Messina | 372,365 | 3.4 | 172 | 3.7 | 2165 |

| Total ports with more than 300,000 passengers | 10,083,240 | 90.8 | 3248 | 69.7 | 3104 |

| Other ports | 1,024,673 | 9.2 | 1410 | 30.3 | 727 |

| Total Italian ports | 11,107,913 | 100.0 | 4658 | 100.0 | 2385 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mangano, S.; Ugolini, G.M. New Opportunities for Cruise Tourism: The Case of Italian Historic Towns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114616

Mangano S, Ugolini GM. New Opportunities for Cruise Tourism: The Case of Italian Historic Towns. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114616

Chicago/Turabian StyleMangano, Stefania, and Gian Marco Ugolini. 2020. "New Opportunities for Cruise Tourism: The Case of Italian Historic Towns" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114616

APA StyleMangano, S., & Ugolini, G. M. (2020). New Opportunities for Cruise Tourism: The Case of Italian Historic Towns. Sustainability, 12(11), 4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114616