Social Capital and Disaster Resilience Nexus: A Study of Flash Flood Recovery in Jeddah City

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Area

- Site # 1 (Rughamah): Exhibited characteristics of middle-class residents and ethnic diversity.

- Site # 2 (Mraykh): Exhibited characteristics of a hub hazard and an overcrowded district lacking in organization and infrastructure and inhabited by people who were lower-class in terms of income and education.

- Site # 3 (Nakeel): Exhibited characteristics of an upper-class neighborhood, high levels of education, and modern construction and organization.

- Site # 4 (Goyzah): Exhibited characteristics of a district with random organization, inhabited by people who were lower than middle class in terms of income and education.

3. Methods and Data Requirements

- Social capital concept in general;

- Damage and relative devastation from the flash flood event both in 2009 and 2011;

- Flash flood responses and recovery;

- Social capital in relation the flash flood hazard; and

- Background information of the respondents.

4. Results

5. Discussion

- The length of stay in a particular community would enhance the resilience of the members in that area. For example, the Mryykh area was dominated by illegal immigrants and during the flash flood event, it was evident that this particular area suffered a lot in comparison to other neighborhoods. Most interviewees expressed a strong sense of togetherness in Nakheel, Rughamah, and Goyzah as compared to Mraykh as they socially interacted for sometime and exchanged their views at different community events;

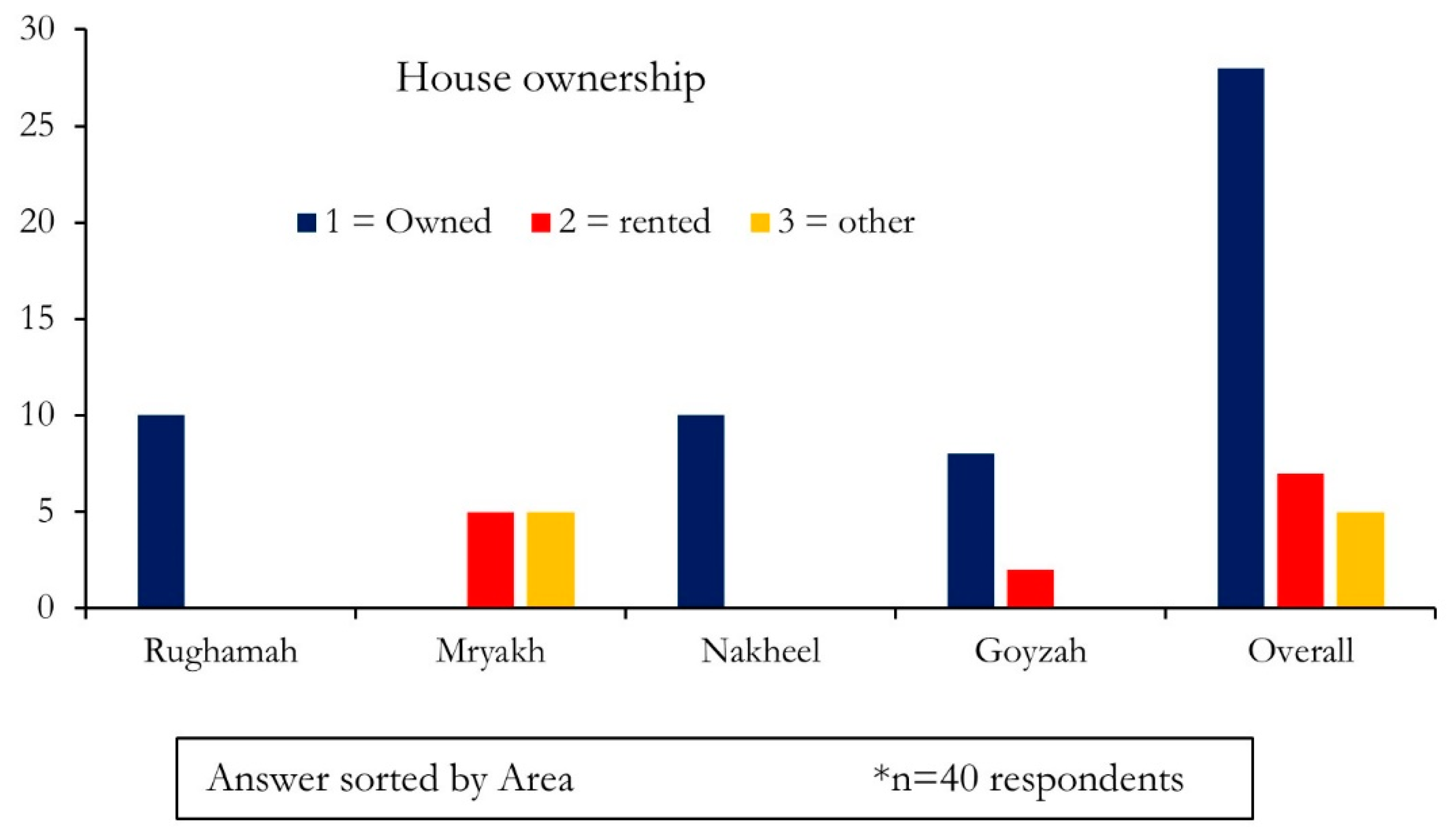

- Housing ownership was considered to be an important factor to enhance resilience. It was noticed that when people own their houses, they had the assets and a strong willingness to go back home after disaster occurred. Usually, people that did not own a house were planning to leave their houses after the disaster;

- The Mraykh area was considered as the poorest area among the four and the recovery was the fastest (see Figure 10). Remarkably, the physical survey revealed that the location of this area had identical exposure to flash floods among the four studied area (see Figure 8). This happened due to the fact that the area contained predominantly with small and single-floor houses with inexpensive furniture and a reduced number of vehicles. They also possessed few electronics, appliances and likely household assets. This point revealed that though some areas were better in terms of economic assets, they struggled to recover quickly in this context;

- Religious faiths in each of the four case study areas contributed varying levels of both low and high levels of resilience. Virtually all of the interviewees who noted the role of preparation also stated that, in the end, what happens is God’s will, i.e., that God has the power to override any preparations that humans might implement. This notion might weaken the community resilience in the study area. However, the participants noted that no matter how prepared a community was or how well houses were constructed; there was still the potential to be affected by a disaster. This could increase resilience amongst people who understood that technology was not infallible, since the respondents recognized that there were always an element of risk upon perceiving the idea of religion;

- Once discussed with the participants in the field, it was noted that most of the people had received information about the flooding from family members, neighbours, and friends, and through social media. Some people received phone calls and text messages from relatives and other family members who were living apart from the community. Some relatives watched the floods, which had been filmed by rescuers, on YouTube, and started to help the victims in their family. It was interesting to note that none of the interviewees received any warning information from government sources, which indicated that the government did not have any disaster management plans or mechanisms in place to save people during sudden flash flood event;

- In this study, we found that the local government responded in the post-recovery processes and increased the resilience of the community in several ways, such as distributing compensation. This situation should have prevailed in the pre-disaster preparedness phase. However, the government organizations had little knowledge of such havoc of flash flood, and thus, organizations commenced the compensation program afterward. The compensation was given based on the reported loss of wealth and assets. The compensation system was somewhat slow due to some formalities, but the monetary involvement was huge. Local government officials were the first to respond with relief aid, albeit with limited manpower. However, volunteers were prompted within a 24-h time period to join with the local government’s team to distribute relief, such as drinking water, safe places for children, transporting injured people to health centers and hospitals, necessary first aid and medicine, etc. Note that government aid was visible mostly in the Nakheel area because many of the municipal officials had their residents in that community;

- Some volunteer and non-government organizations came into help the affected people. However, due to the traditions of some conservative Muslim communities, women organizations played a key role to help the kids and female citizens. Note that male organizations could not help the women and children that much due to the strong cultural obligations. Several notable community-based organizations, such as: Women Charitable Society; Faisaliah Charity Feminism Organization; Neighborhood Society Centers; the First Women’s Charity; Charity House; and Al-Ber Society in the City of Jeddah immediately started helping people in the worst affected areas;

- Religious and cultural organizations (i.e., both public and private) also came to support people, although their missions were to recite holy Quran, exchanging views of religion, and discussion groups of retired officials and landlord. This was important information that we brought up in front that the missions of those groups were different than emergency management but they came to support people during the unwanted event and those organizations could enhance the recovery process;

- Some social organizations, such as: Emdad-SA; City of Jeddah Literary Club; Literary Girls Book Club; and City of Jeddah Cyclist Group also came forward to help the rebuilding and recovery process. Note that if the government would empower them and could define their voluntary roles during any future event, it would enhance the resilience of the communities;

- Residents also informed that they received significant assistance from their relatives. Ali, a resident of the Nakheel district, said “My brother who lives in northern part of the City of Jeddah, offer me to stay at his house until I can re-build my house.” In fact, when asked what gave them strength to recover from the disaster, the majority noted family and neighbours as an important support mechanism. Moreover, the social cohesion was very strong in the case of KSA during the natural events as the religion of Islam supported the idea to support people in need during a disaster.

6. Limitations and Future Scope

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freeman, P.K.; Keen, M.; Mani, M. Being prepared. Financ. Dev. 2003, 341, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunreuther, H. Reducing losses from catastrophes: Role of insurance and other policy tools. Environment 2016, 58, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongman, B.; Winsemius, H.C.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Coughlan De Perez, E.; Van Aalst, M.K.; Kron, W.; Ward, P.J. Declining vulnerability to river floods and the global benefits of adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E2271–E2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bouwer, L.M.; Crompton, R.P.; Faust, E.; Höppe, P.; Pielke, R.A. Confronting disaster losses. Science 2007, 318, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neumayer, E.; Barthel, F. Normalizing economic loss from natural disasters: A global analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jodar-Abellan, A.; Valdes-Abellan, J.; Pla, C.; Gomariz-Castillo, F. Impact of land use changes on flash flood prediction using a sub-daily SWAT model in five Mediterranean ungauged watersheds (SE Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1578–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouad, G.; Al-Hajj, A.; Egbu, C. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Futures ICSF 2017, Sitra, Bahrain, 26–27 November 2017.

- Olsson, J.; Gidhagen, L.; Gamerith, V.; Gruber, G.; Hoppe, H.; Kutschera, P. Downscaling of short-term precipitation from regional climate models for sustainable urban planning. Sustainability 2012, 4, 866–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terti, G.; Ruin, I.; Anquetin, S.; Gourley, J.J. A situation-based analysis of flash flood fatalities in the United States. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourley, J.J.; Hong, Y.; Flamig, Z.L.; Arthur, A.; Clark, R.; Calianno, M.; Ruin, I.; Ortel, T.; Wieczorek, M.E.; Kirstetter, P.E.; et al. A unified flash flood database across the United States. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2013, 94, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Y.; Wetterhall, F.; Cloke, H.L.; Pappenberger, F.; Wilson, M.; Freer, J. Tracking the uncertainty in flood alerts driven by grand. Meteorol. Appl. 2009, 101, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pararas-carayannis, G. Critical assessment of disaster vulnerabilities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—Strategies for mitigating impacts and managing futures. In Proceedings of the First Saudi International Conference on Crisis and Disaster Management, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 12–13 February 2013; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gaurav, K.; Sinha, R.; Panda, P.K. The Indus flood of 2010 in Pakistan: A perspective analysis using remote sensing data. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Khan, A.U.; Ullah, S. Assessment of 2010 flash flood causes and associated damages in Dir Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 16, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, F. Floods in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Unusual Phenomenon and Huge Losses. What Prognoses. E3S Web Conf. 2016, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Aldosary, A.S.; Rahman, M.T. Flood induced vulnerability in strategic plan making process of Riyadh city. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, A.; Belhaj Ali, A. Urban Sprawl in Wadi Goss Watershed (Jeddah City/Western Saudi Arabia) and Its Impact on Vulnerability and Flood Hazards. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2019, 11, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Youssef, A.M.; Sefry, S.A.; Pradhan, B.; Alfadail, E.A. Analysis on causes of flash flood in Jeddah city (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) of 2009 and 2011 using multi-sensor remote sensing data and GIS. Geomatics3 Nat. Hazards Risk 2016, 7, 1018–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, S.A.; Rezgui, Y.; Li, H. Public perception of the risk of disasters in a developing economy: The case of Saudi Arabia. Nat. Hazards 2013, 65, 1813–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-ghamdi, A.M. Planning and Management Issues and Challenges of Flash Flooding Disasters in Saudi Arabia: The Case of Riyadh City. J. Archit. Plan. 2019, 32, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, S.A.; Rezgui, Y.; Li, H. Community resilience factors to disaster in Saudi Arabia: The case of Makkah Province. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2013, 133, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Aldosary, A.S.; Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Reza, I. Vulnerability of flash flooding in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 1807–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, S.A.; Rezgui, Y.; Li, H. Delphi-based consensus study into a framework of community resilience to disaster. Nat. Hazards 2014, 75, 2221–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.; Mourshed, M.; Ameen, R.F.M. Coastal Community Resilience Frameworks for Disaster Risk Management; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 101, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R.; Nakagawa, Y. Social Capital: A Missing Link to Disaster Recovery. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 2004, 22, 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, N.W.; Roy, R.; Lai, C.H.; Tan, M.L. Social capital as a vital resource in flood disaster recovery in Malaysia. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2019, 35, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.J.; Boruff, B.J.; Smith, H.M. When Disaster Strikes... how communities cope and adapt: A social capital perspectives. In Social Capital: Theory Measurement and Outcomes; University of Western Australia: Crawley, WA, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.A. Community resilience, policy corridors and the policy challenge. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, E.; Fouad, A.M.; Khater, E.I.M. Strengthening community emergency preparedness and response in threats and epidemics disasters prevention and management in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2017, 13, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeon, V.; Bates, S. Reviewing composite vulnerability and resilience indexes: A sustainable approach and application. World Dev. 2015, 72, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saja, A.M.A.; Goonetilleke, A.; Teo, M.; Ziyath, A.M. A critical review of social resilience assessment frameworks in disaster management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 35, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreight, R. Resilience as a goal and standard in emergency management. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, B.; Hagan, P. Disasters and communities: Understanding social resilience. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2007, 22, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankoff, G. Comparing vulnerabilities: Toward charting an historical trajectory of disasters. Hist. Soc. Res. 2007, 32, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dynes, R. Social Capital: Dealing with Community Emergencies. Homel. Secur. Aff. 2006, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. On the suitability of assessment tools for guiding communities towards disaster resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 18, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yila, O.; Weber, E.; Neef, A. The Role of Social Capital in Post-Flood Response and Recovery Among Downstream Communities of the BA River, Western Viti Levu, Fiji Islands; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 14, ISBN 9781781908204. [Google Scholar]

- Tolsma, L.; Zezallos, Z. Enhancing Community Development in Adelaide by Building on the Social Capital of South Australian Muslims; Institute for Social Research, University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2009; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin-Gurley, J.; Peek, L.; Loomis, J. Displaced Single Mothers Displaced Single Mothers in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: Resource Needs and Resource Acquisition. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 2010, 28, 170–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans, R.; Priemus, H.; Engbersen, G. Understanding social capital in recently restructured urban neighbourhoods: Two case studies in Rotterdam. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 1069–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S. The Role of Social Capital in Community-Based Urban Solid Waste Management: Case Studies from Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria; University of Waterloo Library: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nurdin, M.R. Religion and Social Capital: Civil Society Organisations in Disaster Recovery in Indonesia; School of Humanities and Social Sciences: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy, B.; Yeung, M.C.H.; Au, A.K.M. Consumer Support for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of Religion and Values. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joakim, E.P.; White, R.S. Exploring the impact of religious beliefs, leadership, and networks on response and recovery of disaster-affected populations: A case study from indonesia. J. Contemp. Relig. 2015, 30, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.I.; Elagib, N.A.; Horn, F.; Saad, S.A.G. Lessons learned from Khartoum flash flood impacts: An integrated assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601–602, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQahtany, A.M.; Abubakar, I.R. Public perception and attitudes to disaster risks in a coastal metropolis of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 44, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eben Saleh, M.A. The transformation of residential neighborhood: The emergence of new urabanism in Saudi Arabian culture. Build. Environ. 2002, 37, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.; Knuiman, M. Creating sense of community: The role of public space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, Z.; As-Sefry, S.; Al-Harithy, S. Probable maximum precipitation and flood calculations for Jeddah area, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špitalar, M.; Gourley, J.J.; Lutoff, C.; Kirstetter, P.E.; Brilly, M.; Carr, N. Analysis of flash flood parameters and human impacts in the US from 2006 to 2012. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A.; Alserayhi, G. Public open space per inhabitant in the city of jeddah. Adv. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borga, M.; Anagnostou, E.N.; Blöschl, G.; Creutin, J.D. Flash flood forecasting, warning and risk management: The HYDRATE project. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, S.N. Global perspectives on loss of human life caused by floods. Nat. Hazards 2005, 34, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.L.T.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Wiering, M.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Matczak, P.; Crabbé, A.; Raadgever, G.T.; Bakker, M.H.N.; Priest, S.J.; et al. Toward more flood resilience: Is a diversification of flood risk management strategies the way forward? Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.B.; Bajracharya, S.R. Case Studies on Flash Flood Risk Management in the Himalayas in Support of Specific Flash Flood Policies; ICIMOD: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2013; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Levees and the National Flood Insurance Program: Improving Policies and Practice; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 9789896540821. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tammar, A.; Abosuliman, S.S.; Rahaman, K.R. Social Capital and Disaster Resilience Nexus: A Study of Flash Flood Recovery in Jeddah City. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114668

Tammar A, Abosuliman SS, Rahaman KR. Social Capital and Disaster Resilience Nexus: A Study of Flash Flood Recovery in Jeddah City. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114668

Chicago/Turabian StyleTammar, Abdurazag, Shougi Suliman Abosuliman, and Khan Rubayet Rahaman. 2020. "Social Capital and Disaster Resilience Nexus: A Study of Flash Flood Recovery in Jeddah City" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114668

APA StyleTammar, A., Abosuliman, S. S., & Rahaman, K. R. (2020). Social Capital and Disaster Resilience Nexus: A Study of Flash Flood Recovery in Jeddah City. Sustainability, 12(11), 4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114668