Abstract

The motivations for clothing companies to implement dedicated certification schemes as sustainability practices has received limited attention in sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) research so far. Therefore, it is important to understand how different rationales for the implementation of certification schemes have developed in the past because they considerably influence the overall success of sustainability management efforts. This paper picks up on this gap and presents the results of an in-depth comparative case study drawing on interviews conducted with five managers of three companies from the clothing sector in 2018 and abductive content analysis. By applying such a qualitative approach, this study explores motivations and benefits as well as elaborates on the implementation of certification schemes in apparel supply chains. It outlines that certification in the clothing sector is driven by strategic factors, marketing considerations, and information considering sustainability aspects. The study also shows that certification schemes may strengthen the marketing and competitive position of clothing companies as well as sustainability awareness in textile and apparel supply chains in general. Finally, a framework conceptualized from the findings of the interviews presents relevant SSCM practices in the clothing industry. Therefore, the present study contributes to theory building in SSCM by confirming and extending previous research on the implementation of certification schemes for sustainability, as well as to practice by examining reasons to apply certification schemes and potential performance outcomes.

1. Introduction

Due to the interdependence of international markets, textile and apparel supply chains have become more globalized as they become even more connected to (and within) developing countries [1]. These increases in outsourcing and international trade have connected a large number of people in emerging and developing countries to the world market. While incidents such as the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh in 2013 have made social and environmental violations in apparel supply chains more obvious, various stakeholders and proactive management approaches have placed sustainability issues along supply chains on the business agenda [2,3]. Due to these changing conditions of economies and societies, clothing companies need to be adaptable and flexible in order to meet new and unpredictable sustainability requirements and other external challenges within this increasingly complex competitive environment [4]. At the present time, the resulting changes are often meant to address unequal working conditions in developing world regions. Accordingly, social and environmental issues along textile and apparel supply chains can lead to operational and reputational risks for clothing companies [5] and their globally fragmented and dynamic supply networks [6,7,8].

In the past, many clothing companies expanded their supply chains into international locations in order to benefit from tariff and trade concessions, lower labor and logistics costs, and closer proximity to their foreign supply markets [9]. Such globalized supply chains offer new procurement possibilities and price advantages, but they also result in the increased complexity of supply networks with multi-tier structures and a greater number of suppliers [10,11]. Furthermore, the lack of direct contractual agreements, power asymmetries, and regional and cultural distances can make it difficult for focal firms to extend their control over globalized multi-tier supply chains in order to maintain or achieve the desired level of sustainability performance [11].

Generally, certification schemes help companies achieving or improving corporate image and reputation, protecting the brand and attracting qualified staff and new customers and, thus, contribute to a firm’s competitive advantage [12]. While drivers and barriers to the implementation of social and environmental practices have been widely analyzed in sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) research (see, e.g., [13]), the understanding of the implementation of sustainability policies through certification merits further research. Therefore, this paper focuses particularly on the motivational aspect of certification schemes for SSCM in the clothing industry. An in-depth case study within this sector has been conducted to determine whether certification can overcome certain barriers to SSCM policy implementation, and to broaden the understanding of what motivates companies to participate in voluntary certification processes. Labelling initiatives have been analyzed for three companies which apply the bluesign certification (in short: bluesign), thereby implementing SSCM policies along their supply chains. The following research questions guided the study:

RQ1: Which motivational factors facilitate the implementation of sustainability standards in apparel supply chains?

RQ2: To which extent are certification schemes adequate to overcome barriers to implementing SSCM practices?

Bluesign defines a best practice SSCM approach for textile companies with regard to its effective implementation of both social and environmental policies. Therefore, this certification scheme can have a significant impact on the successful sustainable policy implementation along global supply chains. The mission of the bluesign certification scheme is defined as “the solution for a sustainable textile production. It eliminates harmful substances right from the beginning of the manufacturing process and sets and controls standards for an environmentally friendly and safe production” (http://www.bluesign.com/). Accordingly, the contribution of the present study is twofold. With regard to theory, we present a conceptual framework confirming, informing and extending previous research on the use of certification schemes in SSCM. With regard to practice, we identify concrete rationales and motives for participating in certification initiatives, as well as hurdles in the implementation and potential performance outcomes. While we solely study the bluesign system, nonetheless, the results are transferable to similar certification schemes.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the relevant literature with regard to sustainability aspects in the clothing industry and related certification practices. The research design of this study is outlined in Section 3, while Section 4 lays out the main results for the cases. Section 4 further provides a combined analysis of the cases that leads to a conceptualization of motivators for implementing SSCM policies along apparel supply chains. The last Section 5 and Section 6 discuss the findings against the literature on SSCM, and conclude the study accordingly.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Supply Chain Management

Supply chains are vulnerable to increasing sustainability needs, and this trend has been amplified by ongoing globalization [14,15]. Focal firms must meet the sustainability demands of their customers, governments, and other stakeholder groups, thereby passing on these requirements to their upstream partners in the supply chain [16]. Hence, companies must recognize the importance of the sustainability performance of their supply chain partners for their own development [17]. Moreover, sustainability risks can arise within a firm’s supply chain [18] because a high level of social or environmental engagement achieved by the focal firm can be brought to naught by the unsustainable behavior of its suppliers or sub-suppliers [19,20]. Hence, the pursuit of social and environmental responsibility on the part of any organization is impossible without incorporating SSCM into their practices [21,22]. In general, SSCM is comprehended as “the management of material, information and capital flows as well as cooperation among companies along the supply chain while taking goals from all three dimensions of sustainable development, i.e., economic, environmental and social, into account which are derived from customer and stakeholder requirement” [16] p. 1700. In this regard, SSCM broadens the view of managing operations and the SC from a narrow focus on economic success only to a wider perspective that includes socio-ecologic factors thereby reflecting all three dimensions of the triple-bottom line [23].

2.2. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Clothing Industry

The triple bottom line (TBL) of sustainability is of particular importance for textile and apparel supply chains [24]. The economic growth of the clothing retail sector in Europe and other industrialized markets has been paralleled by offshoring of textile and apparel production to emerging economies and developing countries [25,26]. In addition, the supply chains of the clothing industry have a strong impact on the environment due to the intensive use of chemicals, water, energy, and land in cotton growth and textile and apparel production [24]. Lastly, the transnational supply chains of the clothing industry have raised awareness of ethical dilemmas, social issues, and societal factors, e.g., in the form of human resource exploitation [27]. Ranging from neglecting workers’ health and safety to the use of child labor, the abuse of labor is often associated with global textile and apparel supply chains [28]. Low levels of transparency and the problem of ethical misconduct in the clothing industry are compounded by a high degree of complexity in global subcontracting relationships [27,29].

Aside from these issues per se, the clothing industry in particular is characterized by globally fragmented and dynamic supply chains [7]. Social and environmental issues have often been observed and reported in clothing production and along textile and apparel supply chains [8]. Clothing companies have to consider social and environmental impacts in nearly every step of their supply networks. This is because they are confronted with the increasing demands of consumer markets and other stakeholder groups that call for higher levels of responsibility and transparency in textile and apparel supply chains [30]. Achieving sustainable production along the whole supply chain is difficult due to the nature of the industry in general, which is characterized by fast fashion trends and short seasons that make clothing production one of the most change-intense economic sectors [30]. Nevertheless, several initiatives have started to enhance sustainability in the international clothing industry [31]. Legal and non-legal standards and customer debates have influenced retailers in the clothing industry to improve the sustainability standards of their suppliers and to commit to codes of conduct (CoCs) [32]. As one particular example, the conventions of the International Labor Organization (ILO) have had a great impact on clothing retailers and prime manufacturers in ensuring that socially acceptable employment and compensation practices in their supply chains are granted and maintained [31].

2.3. SSCM Certification in the Clothing Industry

The use of certification and labeling initiatives is a specific approach toward SSCM in the clothing industry [31,33] which thematically constitutes an adequate field of analysis of SSCM certification for several reasons. First, many apparel firms strive for environmental and social sustainability while also seeking to enhance their image and reputation by communicating their sustainability activities through certification schemes and labeling initiatives [34]. According to Müller et al. [33] p. 512, “certification standards demonstrate a system of pre-settings with their compliance certified by a third party […] [and] this form allows for concrete controls, which have already been identified as a constitutive element of legitimacy.” Earlier work distinguishes between certification and labeling in such a way that to whom the compliance of standards is addressed becomes especially clear. For instance, according to Liu, “while the certificate is a form of communication between seller and buyer, the label is a form of communication with the end consume” [35] pp. 8–9. However, since certification and labeling initiatives are part of a process through which an organization or a product comply to defined standards, this study considers certification and labeling initiatives as one general construct without differentiation. Therefore, in the following sections, the generic term of certification schemes is used interchangeably for certification and labeling initiatives.

However, not every certification scheme in the clothing sector covers all three TBL dimensions, namely the economic, the environmental and the social one. Instead, some certify a company or a product with regard to only one or two dimensions of sustainability. Therefore, the scientific literature differentiates between eco-labeling and social labeling; the corresponding certification schemes thus relate to environmental or social issues, respectively [36,37]. According to Hilowitz [38] p. 217, eco-labels “inform consumers about the environmentally safe mode of production of, or the ecological benefits of using, specific products.” Furthermore, social labels “inform consumers about the social conditions of production in order to assure them that the item or service they are purchasing is produced under equitable working conditions” [38] p. 216. In the past, certification schemes focused mainly on environmental aspects such as raw materials and production waste, but certification schemes borne out of concerns for social and ethical issues have recently became more important [37]. Simplicity and visibility in the perception of their recipients are particular advantages of certification schemes that sustainability reports, CoCs, and other means of communication with consumers do not offer [37]. Furthermore, environmental and social certification schemes can be classified in terms of the object of certification, whether it be the product itself or its manufacturer that can be certified [37].

Almeida [39] as well as Li and Leonas [40] provide detailed information on bluesign’s certification scheme. For comprehensive reviews of literature on SSCM in the clothing industry, the reader is referred to Karaosman et al. [41], Köksal et al. [42] and Yang et al. [43]. Karaosman et al. [41] classify 38 papers on social and environmental sustainability in fashion operations according to product, process and supply chain levels. Their review explains and analyzes examples for product and process certification and sustainability labels in clothing supply chains. Köksal et al. [42] review 45 papers on social sustainability in textile and apparel supply chains under consideration of performance and risk. This study classifies drivers, barriers and enablers of sustainability in focal clothing companies, their suppliers and other stakeholders. Yang et al. [43] present a systematic review of 45 papers on sustainable retailing in the fashion industry.

Since empirical studies on certification schemes in the clothing industry merits further research [41,42,43], scholars often argue on theoretical terms about why many clothing firms adopt certification schemes as a probate SSCM practice and others do not. The extant literature categorizes the motivational factors of clothing companies to implement certification schemes in terms of three main aspects, namely (1) Information, (2) Marketing and (3) Strategy. Thus, certification schemes provide consumers with information about the environmental and social effects of consumption [37]. Furthermore, certification programs may help protect the environment and raise sustainability standards [37] because the social and environmental certification schemes encourage other producers to account for the environmental impact of their manufacturing processes and increase consumers’ awareness of social and environmental issues [44]. In a supply chain context, Carter and Rogers [23] explain that supply chain sustainability has to be part of an integrated strategy. The importance of information for supply chain sustainability is exemplified by Garcia-Torres et al. [45,46] at the examples of sustainability reporting and traceability in supply chains. The relevance of marketing for sustainability is studied by McDonagh and Prothero [47] who provide a synthesis and critical assessment of related literature. To build on this previous research, the present study analyzes company cases based on the core categories proposed by Koszewska [37]. The research design and methods are presented in the next Section 3.

3. Research Design and Methods

The methods applied in this study are rooted in qualitative research, which has been defined by Strauss and Corbin [48] pp. 10–11 as “any type of research that produces findings not arrived at by statistical procedures or other means of quantification.” Strauss and Corbin [48] has stated that the qualitative approach refers particularly to researching organizational functioning. Accordingly, this study aims at exploring the motivating factors for the application of certification schemes in the clothing industry as a driver of SSCM practices. Case studies are well suited to analyze such complex structures because they allow for intense interaction with the informant and draw on multiple sources of information, leading to robust data [49]. Hence, a case study approach was used because the boundaries of the phenomenon and its full scope and context were not entirely described beforehand [50]. We followed an exploratory qualitative case study approach as proposed by Eisenhardt [51] and chose case companies in the clothing industry as embedded units due to the high relevance of certification and labeling initiatives for this sector. Qualitative and primary datasets were gathered from three companies and analyzed to gain further insights into how different rationales for the implementation of such schemes have developed in the past. Details on case sampling, data collection and analysis, and aspects of scientific rigor are described and reflected on in the remainder of this section.

3.1. Case Sampling and Data Collection

Firms that were exclusively sampled were those that held a distinct sustainable supply chain certification, showing comparatively strong engagement in the sustainable management of their supply chains. Suitable clothing companies were identified on bluesign’s certifications website and initially contacted either by email or telephone. Following this sampling methodology, of the initial firms identified as potential participants, three agreed to participate in the study. The number of companies was in line with the suggestions in previous literature in operations management, where studies consider several cases ranging from three to ten [52,53]. The research sample included only clothing companies that were certified as bluesign system partners in order to guarantee “best practice” results. In this way, the research findings were derived from companies that were already concerned with sustainability issues along their supply chain, and, therefore, they were able to provide adequate insights and answers regarding the research questions.

This empirical research project made use of primary and qualitative data sets, consisting of five interviews across three firms. In any case, interviews allow researchers to get close to the point of theoretical saturation [50] while also collecting a relevant amount of data and information that can be processed in one study [51,54]. In sum, five managers from three companies were interviewed. This implied that the number of interviews and functions involved in the interviewing process varied within the overall sample. The interview data was gathered within the year of 2018. Through the multiple case study research approach, different cases and the perspectives of different managers could be analyzed [51]. A case study approach is therefore particularly useful for exploring how and why managers of different firms are integrating sustainability practices into their supply chains. As such, these in-depth case study interviews with responsible corporate managers provided insights into their real business context and the actions taken within their organization [50,55]. Table 1 gives an overview of the interviewees, displaying the department and position of each interviewee:

Table 1.

Companies and interviewees.

3.2. Data Analysis and Coding Scheme

The interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed [56]. The analysis of the data sets followed the approach of Strauss and Corbin [57]. First, the interviews were coded in a deductive manner by applying the categories already present in the literature, and second, they were analyzed inductively by using a matrix spreadsheet. As such, the matrix approach clustered the outcomes and, in this case, the quotes of the managers were denoted into the field of findings which are described as core-categories. On the basis of the defined core-categories, the findings could be allocated into clear topics, while new findings could be derived by adding further sub-categories. Therefore, the results of the conducted interviews can be compared with the existing theoretical and empirical literature. In this way, new research findings can be discovered and added to the currently established body of literature. By doing so, an emergent (rather than predetermined) coding scheme was developed. The final coding scheme is displayed in Table 2, which also displays the emerging codes in each case.

Table 2.

Coding core- and sub-categories.

3.3. Scientific Rigor

Quality procedures with regards to internal validity, external validity, construct validity, and reliability need to be in place when analyzing qualitative data in order to ensure scientific rigor [50]. In terms of external validity, comparisons with the extant literature were conducted, as suggested by Riege [56]. The transcripts were coded by two researchers, thereby ensuring internal validity and inter-coder reliability. Construct validity and reliability were achieved by collecting data from and exposing relevant parallels across multiple sources. Reliability and validity were also ensured by applying a clearly structured and well documented research process [58].

4. Findings

The case companies generally were seeking to professionalize the implementation process of sustainable policies by investing into bluesign certification which provides expert knowledge of the effective incorporation of dedicated sustainability standards along the supply chain. Furthermore, the bluesign certification scheme enables entire supply chains to be certified with the same sustainability criteria by collaborating with all members participating in product creation along the supply chain. In the following, the deductive and inductive findings are presented in detail.

4.1. Deductive Findings

According to Gallastegui [44] and Koszewska [37], one central reason for clothing firms to implement certification schemes is to present information about the effects of consumption and manufacturing. This consideration can be found in the present findings only to some extent. More specifically, only the two German companies stated that they display information through certification schemes. For instance, one company said the following:

I also kind of see it as our educational task; that is what bluesign also says. It is the task of the brands to communicate it [social and environmental sustainability], and here I see it as our responsibility to focus on it more in communication (G1—Head of CSR).

While [G1] perceived it as their educational task and responsibility to communicate and provide information to their customers through certification schemes, [G2] reacted more passively in the same context:

We think that when someone asks us [about bluesign], then that individual will get an answer. However, it is not like this […], of course, when we have bluesign-certified materials that are usually displayed […] let’s say, there exists a hangtag for it. There are themes that are necessary. That is, for example, how the down feathers are processed, or something like that. This is simply because when I do not have transparency here, then the mistrust is really significant, so that things could go in the wrong direction. Therefore, we display certificates, but it is not the case that we broadcast it too much (G2—CEO).

In other words, [G2] actually presents the certifications outwardly, but mainly in order to avoid mistrust rather than to fulfill an educational task. Furthermore, both emphasized that they do not proactively promote certification schemes as means of advertisement. Moreover, Gallastegui [44] has argued that another potential reason to adopt certification schemes is to encourage environmental awareness. This means that certification schemes not only present information about consuming and manufacturing, but they also motivate and encourage consumers to be more aware about sustainability themes. Again, this aspect has only been mentioned by the two German firms. In detail, [G1] clearly stated that creating awareness is one of the main reasons for why they engage in sustainability practices and adopt certification schemes:

In particular, awareness—that is what we consider as our statement. Awareness raising. Because then, everyone can decide by themselves if they want it or not. However, at least they are aware of what they are doing when they buy a t-shirt from Only or ZARA (G1—Head of CSR).

‘Certification schemes, how do they help?’ There are definitely topics which simply do not make sense for every company to audit. However, certification does make a lot of sense—if it is conducted properly. And we say there are two reasons why. The first is definitely the topic of sustainability (G2—CEO).

[G1] points out that they do want to raise awareness, but they are not in a position to force their customers to buy exclusively sustainable clothing articles. The final decision of what the consumers actually buy is the sole responsibility of the consumers themselves. However, the Swedish firm did not mention those aspects at all. Considering a strategic perspective, De Boer [59] has argued that improving the market position or competitive position could be one reason for implementing certification schemes. Within the research findings, only one of the three companies mentioned this aspect:

We consider the standard that bluesign has in this area [chemical and garment materials] as relatively high. Insofar as this is the case, we also think that this will be perceived by the market to a certain extent. […] Since bluesign started, or since we started with bluesign, we saw a great chance that it would be the market standard (G2—CEO).

Thus, [G2] believes that the bluesign certificate could be the market standard in that area, which could therefore be one reason to implement this certification in order to improve the company’s market position. However, the other companies investigated did not refer to this point at all. Another reason companies adopt certification schemes could be that they are responding to external pressure [59]. However, the present research did not find significant support for this suggestion. That is, only [G1] mentioned this point subtly but not explicitly.

It was simply because there was an obligation to join it [bluesign] (G1—Head of CSR).

Therefore, [G1 – Head of CSR] explained that joining bluesign is an obligation while not going into detail about who or what organization had determined bluesign to be an obligatory standard. Due to the term “obligation”, it can be assumed that the driving factor for adopting the certification schemes is external.

4.2. Inductive Findings

Further findings regarding the reasons for applying certification schemes have been found in case studies that have not been clearly discussed in the existing literature yet. Thus, research reveals that there are further potential reasons to adopt certification schemes for clothing companies. As such, [G1] and [G2] explained that they decided to be certified by bluesign because of risk management.

Therefore, it [bluesign] is absolutely just a risk management and quality assurance tool (G1—Head of CSR).

[…] it will probably be the case that we continue to try to make bluesign products but do not advertise them externally. And we do not talk about [it] so much anymore, but rather use them as a risk management tool for us (G2—Head of production).

Hence, both German firms clearly considered the bluesign certification scheme as a risk management tool. Due to the high standards and sustainability principles, bluesign ensures that the companies work with socially and environmentally friendly materials. Thus, it can be assumed that one potential reason to adopt certification schemes is that the firms constitute bluesign as an assurance regarding sustainability issues.

The reason is risk minimization, primarily. This is because when you buy bluesign-approved fabrics or bluesign-approved products, then the likelihood that they are chemically contaminated is really low (G1—Head of CSR).

Of course, I will take a significantly lower risk when I have been absolved of a certain certification process (G1—CEO).

However, while the German firms emphasized the function of risk reduction with respect to bluesign in their case studies, the Swedish firm did not refer to this aspect at all. In addition, the findings indicate that one driving factor for adopting certification schemes is that they provide specific knowledge access. Hence, two firms, [G2] and [S], underlined the possibility of gaining know-how and knowledge by being bluesign-certified.

It [bluesign] was actually well aligned with our system because we primarily saw problems in the materials, and we said that everywhere where we use garments is a black box for us. And there, we can work with bluesign relatively well, and it was a really, really good choice (G2—CEO).

When we joined bluesign it wasn’t because of a label that we could have, but because of the knowledge that they have that we lack, so we absolutely had to have a partner like that. If that means we can have a certification as well, it’s very good (S—CEO).

Consequently, both of the CEOs of [G2] and [S] stated that bluesign gives them access to knowledge that they previously lacked. While [G2] referred to a “black box” in the field of garments, [S] lacked knowledge in the chemical field:

It was the lack of knowledge in the chemical field of electricity and water consumption, but especially chemicals (S—CEO).

Even though [G1] did not explicitly mention that increased access to knowledge could be one potential reason they adopt certification schemes, the other firms underlined this aspect with more certainty. Thus, it can be suggested that certification schemes are not implemented by the firms only because of the displayed label, but rather because of all of the knowledge that is behind that partnership. Furthermore, the research shows that two of the analyzed firms implemented the bluesign certification scheme because of the possibility to network. As such, [G1] described that this condition constitutes the greatest benefit from being certified by bluesign:

Currently, we have not benefited from it [bluesign] so much except for networking. That has been the greatest benefit, I would say, until now (G1—Head of CSR).

Therefore, the certification scheme of bluesign provides the firm with a platform within which all the partners can meet and collaborate.

At bluesign, it is definitely the case that we are system partner and have a really formal collaboration […] and of course, we have regular exchanges with the other system partners. […] we are often in discussions with Mammut, VAUDE, and Schoeffel, and we exchange regularly (G2—Head of Production).

Thus, it can be suggested that the networks and partnering systems behind certification schemes play a crucial role with respect to why firms implement them. That is, gaining access to an existing network facilitates the opportunity to collaborate with partners.

4.3. Conceptual Framework

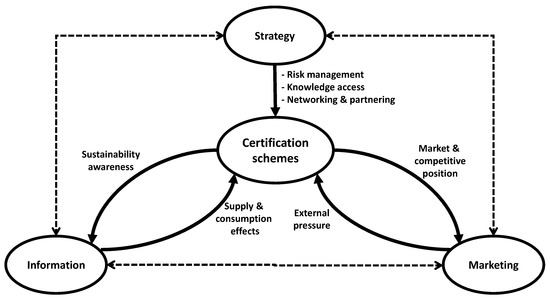

Drawing on the empirical results, we conceptualize a framework that illustrates how Certification schemes interact with Strategy, Information, and Marketing, thereby, strengthening the existing links between these three management areas (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Certification schemes linked to strategy, information and marketing.

The empirical findings provide evidence that risk management and knowledge access as well as networking and partnering opportunities represent strategic factors that encourage the adoption of certification schemes. Moreover, better information on the effects of supply and consumption as well as external pressure may also motivate companies to implement certification schemes. Although just mentioned indirectly in the interviews, external pressures represent an additional category complementing networking which emphasizes outside pressures to implement SSCM by both stakeholders and an increased consumer awareness for sustainability. Regarding TBL performance outcomes, the empirical findings suggest that certification schemes may result in the adoption of higher standards, particularly with respect to an improved competitive market position, and also in increased awareness towards environmental and social issues.

The framework illustrates that certification schemes may serve as a binding link between different management areas. Strategic factors as well as information on supply and consumption or external market pressure may force companies to implement certification schemes, which in turn improve a firm’s sustainability performance.

5. Discussion

Drawing on five semi-structured interviews with managers from three clothing companies, this present work examines potential reasons to apply certification schemes. The findings of the present work suggest that firms adopt certification schemes to inform their customers about the effects of consumption and manufacturing, or to encourage sustainability awareness. The conducted interviews also identify product differentiation or response to external pressure as motivations for certification scheme implementation. Therefore, the empirical findings confirm previous research on these issues. However, the obtained results of the analysis also go beyond what is currently known about certificate scheme implementation in this context. More specifically, the investigated firms adopted the bluesign certificate because of risk management, knowledge assessment, and networking opportunities. Therefore, not only the label itself but also the networking system behind it is a reason to apply certification schemes. While the (S)SCM debate predominantly focuses on the structures, processes, and relationships of organizations, the conceptual framework presented in this paper points toward a broader perspective that reflects different functions and offers a more comprehensive view of sustainability management in supply chains. The remainder of this section discusses the positioning of the present study within four research fields, namely: (i) the interface between operations and marketing, (ii) market position and competition, (iii) the mechanisms of sustainability propagation within and across supply chains, and (iv) risk management.

The present study contributes to the development of SSCM as a cross-functional and integrated topic in the clothing sector. Comparably few earlier works elaborate on the operations-marketing interface see [60] for a review of related models, and even fewer do so from a sustainability perspective [61]. This paper illustrates how certification schemes link strategy, information, and marketing in an SSCM context, thereby endorsing an integrated perspective of marketing, operations, and sustainability. Such a perspective, however, requires (sustainable) business collaboration, particular at the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) [62]. To tackle social operational performance in apparel supply chains for instance, not just multi-national players, but also small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) should apply certification schemes to communicate their sustainability activities. As SMEs in BoP contexts often lack related capabilities, certification schemes provide the opportunity for capability building for sustainable change. On the other side, certification processes are often time demanding, expensive and mainly required in international consumer markets [63], such that the lack of (financial) resources of SMEs requires collaboration with social business orchestrators [62]. Accordingly, certification bodies should consider a more intense interaction with certification holders, at least for SMEs at the BoP.

External pressures are caused by external stakeholder groups outside the supply chain and then propagated across the supply chain by the focal firm [16]. Such external stakeholder groups include government, local communities and NGOs as well as media or investors [18]. Although networking may involve working with such external stakeholder groups [64], we limit networking activities to the propagation of sustainability requirements and the resulting alignment activities within the supply chain thereby following Seuring and Müller [16]. Taking into account specific external pressures, particularly the fierce competition in the clothing sector, eco-labeling and social labeling are approaches for differentiating products [37] in order to achieve a better market position. Nonetheless, products labeled as socially responsible are often traded in niche markets, and moving such products into the mainstream still remains a challenge. Sustainable niche players who incorporate sustainability aspects into their core businesses often trigger market innovations that drive sustainable change [65]. Bigger players increasingly launch marketing campaigns related to certain sustainability issues in order to increase their competitive advantages and market shares in the already saturated market environment of the clothing sector [25]. Such campaigns, however, might just be a matter of “green washing”. Taking into account the empirical findings, the respondents assumed that there would be a change in the market shares between conventional and more sustainable products in the future, which results from the growth of niche players or the replication of bigger brands. In the course of sustainability becoming mainstream, however, the implementation of certification schemes might become an order qualifier for niche players and SMEs rather than an order winner, requiring additional means of differentiation.

Traditional SSCM research explains how focal firms propagate sustainability requirements from their customers to their upstream suppliers [16]. The present study illustrates that the certification schemes implemented by focal firms may raise the customers’ awareness of sustainability, which would complement the upstream direction of sustainability propagation in supply chains with a downstream one. While the present study explicitly points to certification schemes as means of raising the end customers’ awareness of environmental and social issues in the clothing sector, previous research has reported similar results in other industry sectors. For the logistics sector, for instance, Gruchmann et al. [66] has emphasized that easily accessible information can allow for additional hurdles to be avoided by consumers and other stakeholders in realizing more sustainable consumption patterns. However, they also conclude that the communicated content needs to be transparent and must be based on reliable indicators while avoiding overburdening with content, which is also true for the clothing sector [37]. With regard to multi-tier SSCM, managing upstream supply chain tiers beyond the first-tier level fosters the involvement of third parties, such as auditing agencies [67]. Although the empirical findings presented here only implicitly provide evidence that certification schemes help spread sustainable practices to sub-suppliers, the extant literature points in this direction e.g., [20]. For instance, Grimm et al. [11] found that sub-supplier management is driven by public attention directed toward first-tier suppliers, risks of sub-supplier misbehavior (as perceived by focal companies), and the focal company’s channel power. Accordingly, future work could extend the research-applied design to lower supply chain tiers.

With regard to risk management, it is important to identify and evaluate key sustainability risks [68]. Organizations increasingly manage their social and environmental performance by achieving certificates from standard-setting notified bodies, which also increases their legitimacy among their stakeholders [33]. In recent years, numerous sustainability standards have been developed. The empirical findings suggest that these standards are implemented to achieve structured risk management. Hence, standard-setting notified bodies and regulatory authorities may have an impact on an organization’s strategic intent [69]. Therefore, sustainability standards can be seen as a collection of formalized practices and routines that allow for the evaluation of a company’s progress toward becoming a more sustainable organization. Such processes also provide learning opportunities through knowledge access. As confirmed by the empirical results reported here, practices such as workforce training and employer-guided coaching promote organizational innovation and determine key capabilities for achieving a (sustainable) competitive advantage [69]. Learning opportunities may lead to an even more enhanced innovation climate within the organization [70]. Besides developing internal capabilities for sustainability through knowledge access, recent research has shown that cross-organizational capabilities stimulate organizational change [71]. In line with such findings, the empirical results reported here point to networking as an additional source of information that facilitates inter-organizational capabilities.

6. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

The present study has identified several reasons why clothing companies implement certification schemes. Moreover, the interplay of certification schemes with strategy, marketing, and information has been illustrated, explained, and conceptualized. By answering the proposed research questions by means of an explorative and qualitative research design, the present study provides valuable insights into further motivations for engaging in certification schemes in apparel supply chains, along with the perceived and derived benefits. Besides the theoretical contribution, practitioners might benefit from the insights of the present study. While a previous research strongly emphasized the value of certification schemes with regard to marketing and customer information, we shifted the focus to the potentials internal gains with regard to learning, collaboration/networking, and risk management. Particular for those companies where the marketing potential of certification is limited, certification schemes still can be useful to facilitate organizational change for sustainability.

Nonetheless, the present study also exhibits some limitations. These limitations, in turn, provide opportunities for future research activities. First, the sample only covers five interviews with managers from three firms from Europe. Therefore, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the obtained results. For better comparability among the case studies, further research, e.g., in other countries or sectors, is necessary to identify additional factors influencing certification scheme implementation for SSCM. Second, since the research is based on data gathered by qualitative interviews, the findings are subject to social desirability bias. Additional research into this topic is also needed to validate and test the conceptual framework of this work. Therefore, conducting further case studies and implementing other research approaches such as surveying is recommended. Furthermore, analyzing companies with different organizational sizes, national origins, or industry sectors could be helpful to further validate the presented results or gain new insights. Regarding reasons for adopting certification schemes, certification schemes other than bluesign could also be included and addressed in the interview guidelines in order to obtain a broader range of statements and more generalizable results.

Author Contributions

The study represents joint work of all three authors. N.O. conducted the research design, data collection, and data analysis of the interviews. N.O. also mainly contributed to the writing of the manuscript. T.G. and M.B. supported the writing of the manuscript and particularly added the conceptual framework and the discussion section. Editing of the draft versions was mainly done by T.G. and M.B. while reworking of the final manuscript was carried out by T.G. and N.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the Sustainability Special Issue on “Sustainable Operations and Supply Chain Management” edited by the authors of this paper. The authors thank MDPI for enabling and publishing the Special Issue and for supporting our Guest Editor activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Oelze, N. Implementierung von Umwelt-und Sozialstandards entlang der Wertschoepfungskette: Lernen aus den Erfahrungen fuehrender Unternehmen. In CSR und Beschaffung; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann-Pauly, D.; Labowitz, S.; Banerjee, N. Closing Governance Gaps in Bangladesh’s Garment Industry—The Power and Limitations of Private Governance Schemes; SSRN 2577535; SSRN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, S.; Chesney, T.; Gruchmann, T.; Trautrims, A. Diffusion of labor standards through supplier-subcontractor networks: An agent-based model. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, M.; Gruchmann, T.; Oelze, N. Sustainable Supply Chain Management? A Conceptual Framework and Future Research Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S. Supply chain specific? Understanding the patchy success of ethical sourcing initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmelhainz, M.A.; Adams, R.J. The apparel industry response to “sweatshop” concerns: A review and analysis of codes of conduct. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 1999, 35, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiengarten, F.; Pagell, M.; Fynes, B. Supply chain environmental investments in dynamic industries: Comparing investment and performance differences with static industries. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, M.; Seuring, S. Social and environmental risk management in supply chains: A survey in the clothing industry. Logist. Res. 2015, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixell, M.J.; Gargeya, V.B. Global supply chain design: A literature review and critique. Transp. Res. Part Logist. Transp. Rev. 2005, 41, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplin, J. Integrating environmental and social standards into supply management—An action research project. In Research Methodologies in Supply Chain Management; Physica-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 381–396. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, J.H.; Hofstetter, J.S.; Sarkis, J. Exploring sub-suppliers’ compliance with corporate sustainability standards. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1971–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Massa, I. Social values and sustainability: A survey on drivers, barriers and benefits of SA8000 certification in Italian firms. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4120–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabat, A.; Govindan, K. An analysis of the drivers affecting the implementation of green supply chain management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morali, O.; Searcy, C. A review of sustainable supply chain management practices in Canada. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S. A review of modeling approaches for sustainable supply chain management. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebs, T.; Brandenburg, M.; Seuring, S.; Stohler, M. Stakeholder influences and risks in sustainable supply chain management: A comparison of qualitative and quantitative studies. Bus. Res. 2018, 11, 197–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, R.; Wagner, B.; Gimenez, C.; Tachizawa, E.M. Extending sustainability to suppliers: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 531–543. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, P.; Seuring, S. A three-dimensional framework for multi-tier sustainable supply chain management. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 23, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageron, B.; Gunasekaran, A.; Spalanzani, A. Sustainable supply management: An empirical study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L. Rhetoric and reality of corporate greening: A view from the supply chain management function. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warasthe, R.; Brandenburg, M. Sourcing organic cotton from African countries—Potentials and risks for the apparel industry supply chain. IFAC Pap. OnLine 2018, 51–30, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, P.; Towers, N. Determining the antecedents for a strategy of corporate social responsibility by small-and medium-sized enterprises in the UK fashion apparel industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 337–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M.; Laursen, S.E.; de Rodriguez, C.M.; Bocken, N.M. Well dressed?: The present and future sustainability of clothing and textiles in the United Kingdom. J. Home Econ. Inst. Aust. 2015, 22, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel, O. The paradox of extralegal activism: Critical legal consciousness and transformative politics. Harv. L. Rev. 2006, 120, 937. [Google Scholar]

- Gam, H.J.; Banning, J. Addressing sustainable apparel design challenges with problem-based learning. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2011, 29, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCarthy, B.L.; Jayarathne, P.G.S.A. Supply Network Structures and SMEs: Evidence from the International Clothing Industry. In Managing Cooperation in Supply Network Structures and Small or Medium-Sized Enterprises; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J.; Schmitz, H. Governance in global value chains. IDS Bull. 2001, 32, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Dos Santos, V.G.; Seuring, S. The contribution of environmental and social standards towards ensuring legitimacy in supply chain governance. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaus, K. Zertifizierung in der Textilbranche—Einblicke in die Arena nachhaltiger Strategien. In Zertifizierung als Erfolgsfaktor; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P. Environmental and Social Standards, Certification and Labelling for Cash Crops; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2003; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Koszewska, M. Social and eco-labelling of textile and clothing goods as means of communication and product differentiation. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2011, 19, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Koszewska, M. Life cycle assessment and the environmental and social labels in the textile and clothing industry. In Handbook of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Textiles and Clothing; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston/Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Hilowitz, J. Social labelling to combat child labour: Some considerations. Int’l Lab. Rev. 1997, 136, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, L. Ecolabels and Organic Certification for Textile Products. In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Leonas, K.K. Trends of Sustainable Development Among Luxury Industry. In Sustainable Luxury. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Karaosman, H.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Brun, A. From a systematic literature review to a classification framework: Sustainability integration in fashion operations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social sustainable supply chain management in the textile and apparel industry—A literature review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Song, Y.; Tong, S. Sustainable retailing in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarraga Gallastegui, I. The use of eco-labels: A review of the literature. Eur. Environ. 2002, 12, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torres, S.; Rey-Garcia, M.; Albareda-Vivo, L. Effective disclosure in the fast-fashion industry: From sustainability reporting to action. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torres, S.; Albareda, L.; Rey-Garcia, M.; Seuring, S. Traceability for sustainability? Literature review and conceptual framework. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainability marketing research: Past, present and future. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 1186–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M. Understanding the factors that enable and inhibit the integration of operations, purchasing and logistics. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 459–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Choi, T.Y. Supplier-supplier relationships in the buyer-supplier triad: Building theories from eight case studies. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 24, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Wu, Z. Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 exemplars. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2009, 45, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Hak, T. Methodology in Business Research; Blutterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; Heilderberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Riege, A.M. Validity and reliability tests in case study research: A literature review with “hands-on” applications for each research phase. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2003, 6, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S. Assessing the rigor of case study research in supply chain management. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2008, 13, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J. Sustainability labelling schemes: The logic of their claims and their functions for stakeholders. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2003, 12, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C. A review of marketing-operations interface models: From co-existence to coordination and collaboration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 125, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Iyer, G.R.; Mehrotra, A.; Krishnan, R. Sustainability and business-to-business marketing: A framework and implications. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Chowdhury, I.N.; Huq, F.A.; Heinemann, K. Social business collaboration at the bottom of the pyramid: The case of orchestration. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossle, M.B.; Neutzling, D.M.; Wegner, D.; Bitencourt, C.C. Fair trade in Brazil: Current status, constraints and opportunities. Organ. Soc. 2017, 24, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frostenson, M.; Prenkert, F. Sustainable supply chain management when focal firms are complex: A network perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruchmann, T.; Schmidt, I.; Lubjuhn, S.; Seuring, S.; Bouman, M. Informing logistics social responsibility from a consumer-choice-centered perspective. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachizawa, E.; Wong, Y. Towards a theory of multi-tier sustainable supply chains: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske, P.; Land, A.; Seuring, S. Sustainable supply chain management practices and dynamic capabilities in the food industry: A critical analysis of the literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management: Organizing for Innovation and Growth; Oxford University Press on Demand: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon-Byrne, L.; Harney, B. Microfoundations of dynamic capabilities for innovation: A review and research agenda. Ir. J. Manag. 2017, 36, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amui, L.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Kannan, D. Sustainability as a dynamic organizational capability: A systematic review and a future agenda toward a sustainable transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).