How You Deal with Your Emotions Is How You Drive. Emotion Regulation Strategies, Traffic Offenses, and the Mediating Role of Driving Styles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

3.2. Correlational Analysis

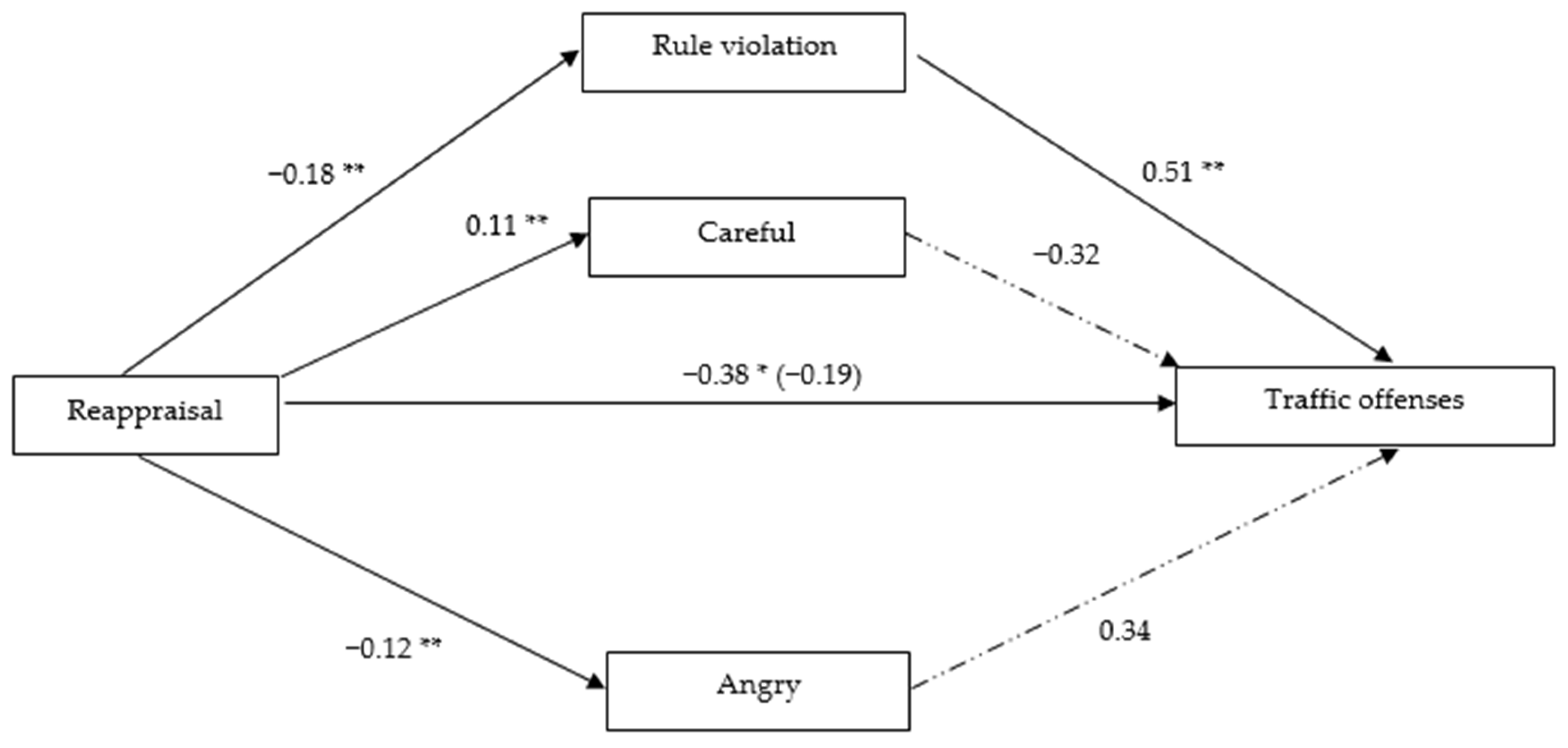

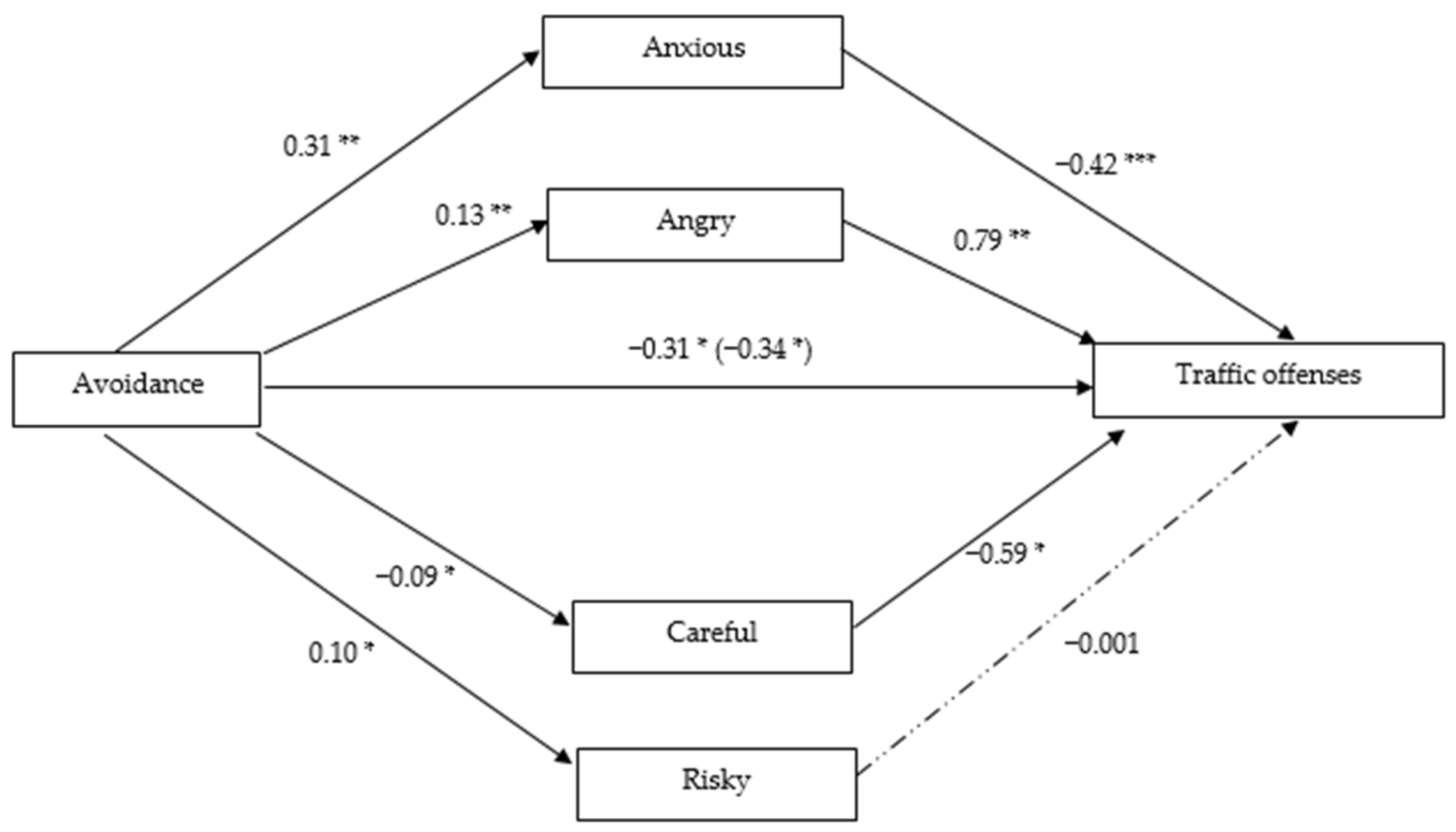

3.3. Testing for Mediation

3.4. Emotion Regulation Strategies and Driving Styles According to the Number of Traffic Offenses

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization, Global Status Report on Road Safety; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Corbett, C.; Simon, F. Decisions to break or adhere to the rules of the road, viewed from the rational choice perspective. Brit. J. Criminol. 1992, 32, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, P.; af Wåhlberg, A.; Freeman, J.; Watson, B.; Watson, A. Predicting crashes using traffic offences. A meta-analysis that examines potential bias between self-report and archival data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Traffic Police Statistics. Available online: https://www.politiaromana.ro/ro/structura-politiei-romane/unitati-centrale/directia-rutiera/statistici (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Farooq, D.; Moslem, S.; Duleba, S. Evaluation of driver behavior criteria for evolution of sustainable traffic safety. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niu, S.F.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, L.; Li, H.Q. Effects of Different Intervention Methods on Novice Drivers’ Speeding. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Skvirsky, V. The multidimensional driving style inventory a decade later: Review of the literature and re-evaluation of the scale. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 93, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvanfar, A.; Shafaghat, A.; Muhammad, N.Z.; Ferwati, M.S. Driving behaviour and sustainable mobility—policies and approaches revisited. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holman, A.C.; Havârneanu, C.E. The Romanian version of the multidimensional driving style inventory: Psychometric properties and cultural specificities. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 35, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faílde-Garrido, J.M.; García-Rodríguez, M.A.; Rodríguez-Castro, Y.; González-Fernández, A.; Fernández, M.L.; Fernández, M.V.C. Psychosocial determinants of road traffic offences in a sample of Spanish male prison inmates. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 37, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poó, F.M.; Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Ledesma, R.D.; Díaz-Lázaro, C.M. Reliability and validity of a Spanish-language version of the multidimensional driving style inventory. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2013, 17, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Mikulincer, M.; Gillath, O. The multidimensional driving style inventory—scale construct and validation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2004, 36, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, J.L.; Doncel, P.; Gugliotta, A.; Castro, C. Which drivers are at risk? Factors that determine the profile of the reoffender driver. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 119, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagberg, F.; Selpi; Bianchi Piccinini, G.F.; Engström, J. A review of research on driving styles and road safety. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 1248–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwyther, H.; Holland, C. The effect of age, gender and attitudes on self-regulation in driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Yehiel, D. Driving styles and their associations with personality and motivation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poó, F.M.; Ledesma, R.D. A study on the relationship between personality and driving styles. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2013, 14, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingus, T.A.; Guo, F.; Lee, S.E.; Antin, J.F.; Perez, M.; Buchanan-King, M.; Hankey, J. Driver crash risk factors and prevalence evaluation using naturalistic driving data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2636–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eboli, L.; Mazzulla, G.; Pungillo, G. How drivers’ characteristics can affect driving style. Transp Res Procedia 2017, 27, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffenbacher, J.L.; Deffenbacher, D.M.; Lynch, R.S.; Richards, T.L. Anger, aggression, and risky behavior: A comparison of high and low anger drivers. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulleberg, P.; Rundmo, T. Personality, attitudes and risk perception as predictors of risky driving behaviour among young drivers. Saf. Sci. 2003, 41, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Zhang, W. Sadder but wiser? Effects of negative emotions on risk perception, driving performance, and perceived workload. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kovácsová, N.; Lajunen, T.; Rošková, T. Aggression on the road: Relationships between dysfunctional impulsivity, forgiveness, negative emotions, and aggressive driving. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 42, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trick, L.M.; Brandigampola, S.; Enns, J.T. How fleeting emotions affect hazard perception and steering while driving: The impact of image arousal and valence. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2001, 10, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual Foundations. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.C.; Malmstadt, J.R.; Larson, C.L.; Davidson, R.J. Suppression and enhancement of emotional responses to unpleasant pictures. Psychophysiology 2000, 37, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, A.A.; Loucks, E.B.; Buka, S.L.; Kubzansky, L.D. Divergent associations of antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation strategies with midlife cardiovascular disease risk. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 48, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- English, T.; John, O.P.; Srivastava, S.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation and peer-rated social functioning: A 4-year longitudinal study. J. Res. Pers. 2012, 46, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cludius, B.; Mennin, D.; Ehring, T. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion 2020, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzlaff, R.M.; Wegner, D.M. Thought suppression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 59–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L.D.; Overall, N.C. Suppression and expression as distinct emotion-regulation processes in daily interactions: Longitudinal and meta-analyses. Emotion 2018, 18, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, T.; Eldesouky, L. We’re not alone: Understanding the social consequences of intrinsic emotion regulation. Emotion 2020, 20, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilman, R.M.; Crişan, L.G.; Houser, D.; Miclea, M.; Miu, A.C. Emotion regulation and decision making under risk and uncertainty. Emotion 2010, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K.G.; Bissett, R.T.; Pistorello, J.; Toarmino, D.; Polusny, M.A.; Dykstra, T.A.; Batten, S.V.; Bergan, J.; et al. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. Psychol. Rec. 2004, 54, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, M.; Singhal, A. The emotional side of cognitive distraction: Implications for road safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 50, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deffenbacher, J.L. A review of interventions for the reduction of driving anger. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 42, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon, M.; Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. Driven by emotions: The association between emotion regulation, forgivingness, and driving styles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trógolo, M.A.; Melchior, F.; Medrano, L.A. The role of difficulties in emotion regulation on driving behavior. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2014, 6, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeibokaitė, L.; Endriulaitienė, A.; Sullman, M.J.; Markšaitytė, R.; Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, K. Difficulties in emotion regulation and risky driving among Lithuanian drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2017, 18, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parlangeli, O.; Bracci, M.; Guidi, S.; Marchigiani, E.; Duguid, A.M. Risk perception and emotions regulation strategies in driving behaviour: An analysis of the self-reported data of adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Hum. Factors Ergon. 2018, 5, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W.; Donnelly, J. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 3rd ed.; Cengage Learning: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter, F.; Wallnau, L. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 8th ed.; Wadswort: Belmont, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Methodology in the social sciences. In Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Yau, K.K.; Chen, G. Risk factors associated with traffic violations and accident severity in China. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 59, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Aldao, A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth, N.; Symmons, M. Driving to Reduce Fuel Consumption and Improve Road Safety. Monash University Accident Research Centre. Available online: http://acrs.org.au/files/arsrpe/RS010036.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Majid, M.Z.A.; Bigah, Y.; Keyvanfar, A.; Shafaghat, A.; Mirza, J.; Kamyab, H. Green Highway Development Features to Control Stormwater Runoff Pollution. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2015, 4, 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Carrese, S.; Gemma, A.; La Spada, S. Impacts of Driving Behaviours, Slope and Vehicle Load Factor on Bus Fuel Consumption and Emissions: A Real Case Study in the City of Rome. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 87, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alpha | Mean Inter-Item Correlation | Min | Max | M | SD | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reappraisal | 0.74 | 0.34 | 1 | 7 | 4.73 | 0.88 | −0.35 (0.10) | 1.06 (0.20) |

| Expressive suppression | 0.55 | 0.23 | 1 | 7 | 3.68 | 0.94 | 0.16 (0.10) | 0.44 (0.20) |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.74 | 0.28 | 1 | 7 | 2.56 | 1.04 | 0.78 (0.10) | 0.32 (0.20) |

| MDSI—rule violation | 0.84 | 0.47 | 1 | 6 | 3.09 | 1.18 | 0.17 (0.10) | −0.80 (0.20) |

| MDSI—anxious | 0.80 | 0.48 | 1 | 6 | 2.01 | 0.95 | 1.01 (0.10) | 0.58 (0.20) |

| MDSI—careful | 0.73 | 0.29 | 1 | 6 | 4.97 | 0.74 | −0.92 (0.10) | 0.85 (0.20) |

| MDSI—risky | 0.75 | 0.34 | 1 | 6 | 2.63 | 0.93 | 0.53 (0.10) | 0.004 (0.20) |

| MDSI—angry | 0.81 | 0.35 | 1 | 6 | 3.01 | 0.92 | 0.24 (0.10) | −0.30 (0.20) |

| MDSI—distress | 0.61 | 0.29 | 1 | 6 | 4.17 | 1.01 | −0.45 (0.10) | −0.25 (0.20) |

| MDSI—dissociative | 0.70 | 0.28 | 1 | 6 | 1.91 | 0.70 | 1.18 (0.10) | 1.73 (0.20) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Traffic offenses | - | −0.12 ** | 0.04 | −0.14 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.09 * | −0.16 ** | 0.12 * | 0.20 ** | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.31 ** | −0.14 ** |

| 2. Reappraisal | - | 0.03 | −0.14 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.03 | 0.14 ** | −0.08 | −0.11 ** | 0.11 ** | −0.01 | −0.09 * | 0.11 * | |

| 3. Expressive suppression | - | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.09 * | ||

| 4. Experiential avoidance | - | 0.02 | 0.34 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.10 * | 0.14 ** | −0.03 | 0.30 ** | −0.12 * | 0.12 ** | |||

| 5. MDSI—rule violation | - | −0.03 | −0.39 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.08 | −0.18 ** | ||||

| 6. MDSI—anxious | - | −0.23 ** | −0.06 | 0.12 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.01 | 0.14 ** | |||||

| 7. MDSI—careful | - | −0.45 ** | −0.48 ** | 0.03 | −0.28 ** | 0.08 | 0.14 ** | ||||||

| 8. MDSI—risky | - | 0.59 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.14 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.20 ** | |||||||

| 9. MDSI—angry | - | 0.20 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.10 * | −0.10 * | ||||||||

| 10. MDSI—distress | - | −0.01 | −0.22 ** | −0.03 | |||||||||

| 11. MDSI—dissociative | - | −0.02 | 0.13 ** | ||||||||||

| 12. Age | - | −0.07 | |||||||||||

| 13. Gender | - |

| Bias Corrected | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimate | SE | 95% Lower | 95% Upper | |

| Reappraisal | ||||

| Rule violation | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.1922 | −0.0191 |

| Careful | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.0997 | 0.0082 |

| Angry | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.1112 | 0.0065 |

| Avoidance | ||||

| Anxious | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.2317 | −0.0395 |

| Angry | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.0350 | 0.1867 |

| Careful | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.0090 | 0.1250 |

| Risky | −0.001 | 0.02 | −0.0452 | 0.0385 |

| Number of Traffic Offenses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (N = 321) | High (N = 233) | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | t | |

| Reappraisal | 4.79 (0.87) | 4.64 (0.89) | 1.97 * |

| Expressive suppression | 3.61 (0.97) | 3.78 (0.90) | −02.09 * |

| Avoidance | 2.67 (1.06) | 2.43 (1.00) | 2.55 * |

| MDSI—Rule violation | 2.79 (1.10) | 3.51 (1.16) | −7.44 ** |

| MDSI—Anxious | 2.07 (0.97) | 1.93 (0.93) | 1.75 |

| MDSI—Careful | 5.08 (0.73) | 4.84 (0.74) | 3.72 ** |

| MDSI—Risky | 2.49 (0.89) | 2.83 (0.97) | −4.20 ** |

| MDSI—Angry | 2.84 (0.89) | 3.24 (0.92) | −5.14 ** |

| MDSI—Distress | 4.16 (1.00) | 4.19 (1.02) | −0.25 |

| MDSI—Dissociative | 1.92 (0.74) | 1.89 (0.65) | 0.71 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holman, A.C.; Popușoi, S.A. How You Deal with Your Emotions Is How You Drive. Emotion Regulation Strategies, Traffic Offenses, and the Mediating Role of Driving Styles. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124929

Holman AC, Popușoi SA. How You Deal with Your Emotions Is How You Drive. Emotion Regulation Strategies, Traffic Offenses, and the Mediating Role of Driving Styles. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124929

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolman, Andrei C., and Simona A. Popușoi. 2020. "How You Deal with Your Emotions Is How You Drive. Emotion Regulation Strategies, Traffic Offenses, and the Mediating Role of Driving Styles" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124929

APA StyleHolman, A. C., & Popușoi, S. A. (2020). How You Deal with Your Emotions Is How You Drive. Emotion Regulation Strategies, Traffic Offenses, and the Mediating Role of Driving Styles. Sustainability, 12(12), 4929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124929