The Analysis of Stress and Negative Effects Connected with Scientific Work among Polish Researchers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Problems with working hours, workload, and pace of work;

- Control methods used to measures levels of autonomy, pacing, and timing of scholars working methods;

- Peer support and the degree of help and respect from other university staff including colleagues;

- Managerial support and their supportive behaviors. Help from line managers and also the organization itself. The examples of this help are encouragement and availability of feedback;

- Relationships between university staff and levels of conflict in the workplace. In this case, the very important problems are bullying behavior and harassment;

- The extent to which researchers believe that their work is important and fits into the aims of the particular organization; and

- Change which reflects how well changes in the university environment are managed and communicated.

- Burnout is when a particular person has pushed creative energy beyond the borders.

- Burnout is when a person is subjected to continuous job-related stress, especially in situations where one has the loss of emotional, physical, and mental energy.

- Burnout is the lack of motivation and desire to achieve a sufficient level of balance among professorial responsibilities in the job, especially in areas of teaching, service, scholarship, peer relationships, and student care-giving.

- Burnout is when one experiences problems connected with detachment (especially detachment from staff, students, peers, and clients) and a decrease of satisfaction or sense of well-being.

- Burnout is frustration, fatigue, or apathy resulting from long periods of stress, intense activity, or overwork.

- Burnout is neither a neurosis nor physical ailment. It is an inability to mobilize one’s capabilities and interest or loss of will.

- Recognize symptoms of burnout regarding their performance, body language, communication style, and attitudes.

- Willingness to make changes.

- Talk to someone, for example, counselor, friend, family physician, or doctors specializing in stress.

- Balance their lifestyle and analyze what is important in their life.

- Develop a plan to overcome the stressors. Set targets and goals for change.

- Join in some stress management programs.

- Read books and papers about burnout, stress, and suggested coping mechanisms.

- Negotiate with the department authorities to temporarily change their professional responsibilities.

- Take a sabbatical or personal leave.

- Reverse negative vocabulary and also negative thinking.

- Explore some relaxation exercises.

- Find a hobby.

- Explore about assistance in these problems with the university’s human resources department.

- depression (75%),

- panic attacks (42%),

- eating disorder (15%),

- self-harm (11%),

- obsessive-compulsive disorder (11%),

- alcoholism (11%),

- post-traumatic stress disorder (9%),

- other mental health disorder (7%),

- bipolar disorder (4%),

- drug addiction (2%).

- In many surveys, UK higher education teachers have reported that their well-being is worse compared with staff well-being in other types of organizations (including health, education, and social work). They compared areas of work demands, support provided by managers, change management, and clarity about one’s role.

- The proportions of both scholars and postgraduate students which have a risk of having or developing a problem with mental health. This proportion is based on, for example, self-reported data. It is generally higher than we can observe among other working populations.

- The main factors that are associated with the development of depression and other typical mental health problems among PhD students are work–life conflict, high levels of work demands, poor support from the supervisor, low job control, and exclusion from the decision making processes.

- Studies pinpoint that academic staff involved in research on sensitive topics as abuse or trauma can be emotionally affected by the problems they encounter in their research. They should receive better support for university authorities to mitigate the possible negative impacts of this work. The problem of abuse in the university environment was also pointed out by Oleksinienko [99].

- We can observe that job stress levels and poor workplace conditions can contribute to reduced productivity of academic staff. It can be both through absence and also through presentism. Because of that researchers can attend work and are less productive.

- Implementation of detailed personal development plans, 360-degree feedback, group sessions, and mentoring. Workshops with staff can be useful to increase the level of understanding and engagement of researchers into the strategic plan, online resources, and communication, vice-chancellor-led open meetings, etc.

- Briefings, stress risk assessment, free gym membership, training, and solution groups.

- Academic and non-academic middle managers can participate in a program connected with individual executive coaching [100].

- Establishment of workplace policies useful for stress reduction [101].

- Suicide-prevention training program [104].

- Mindfulness six-week program to decrease stress levels [105].

3. Materials and Methods

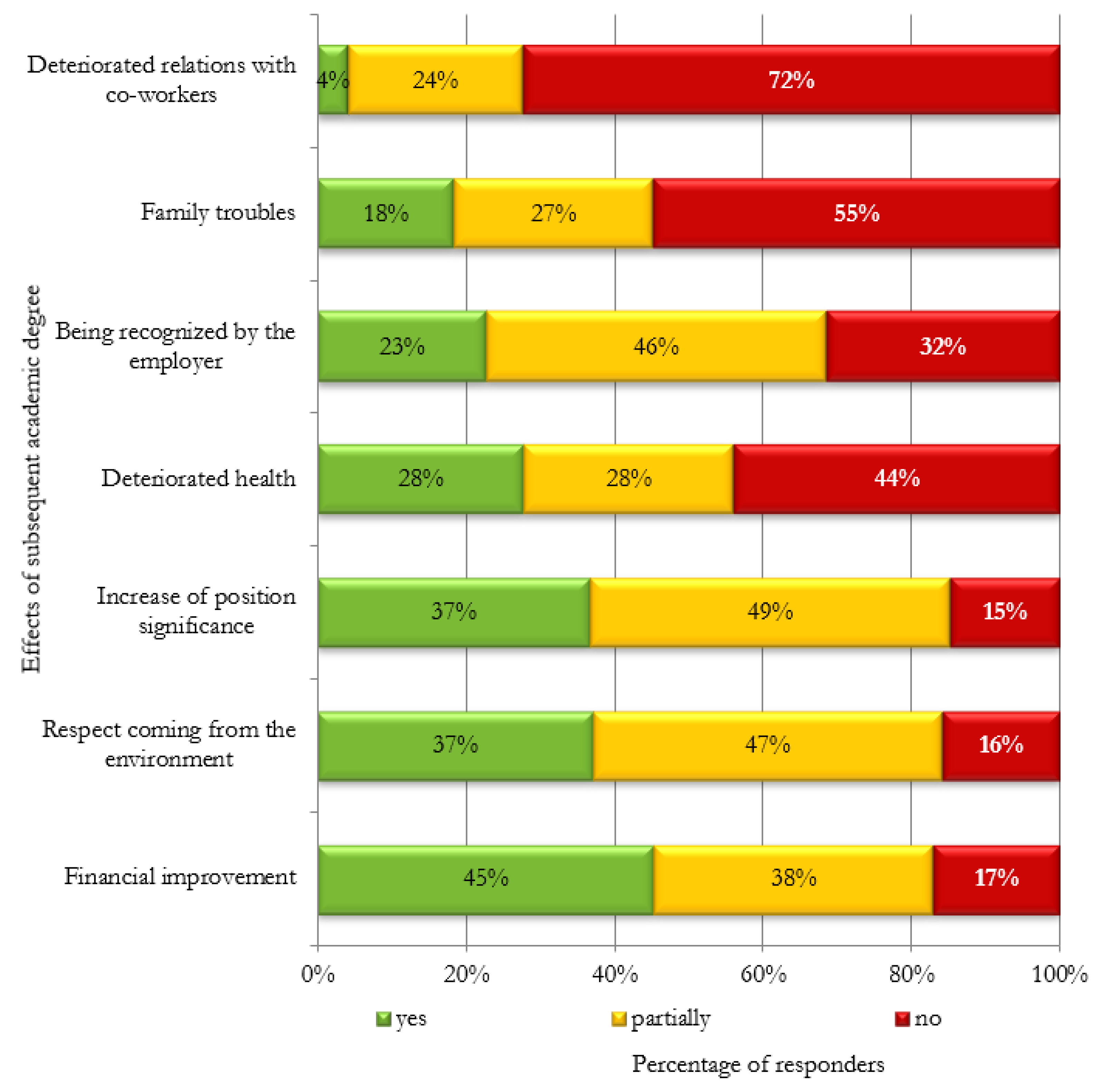

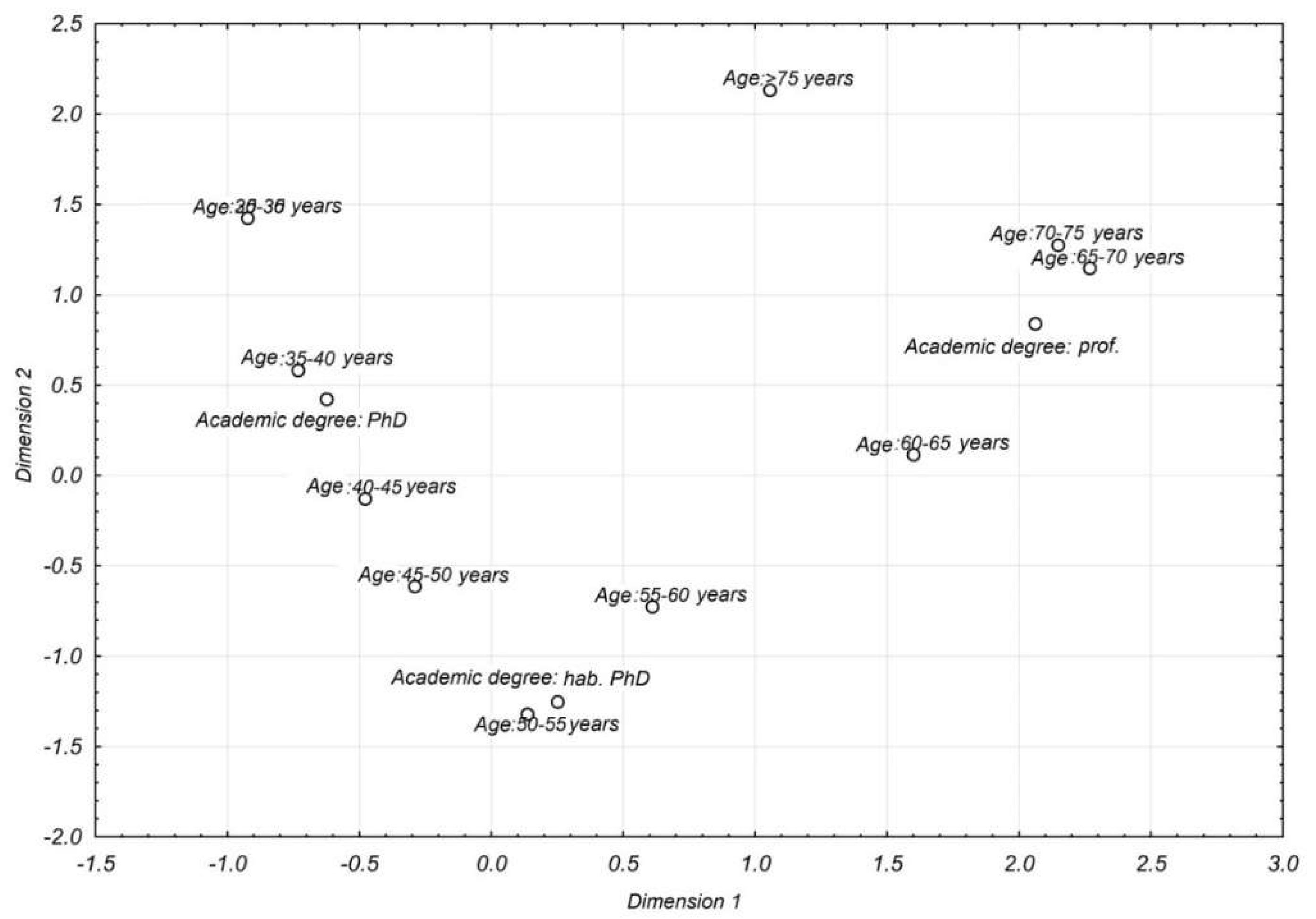

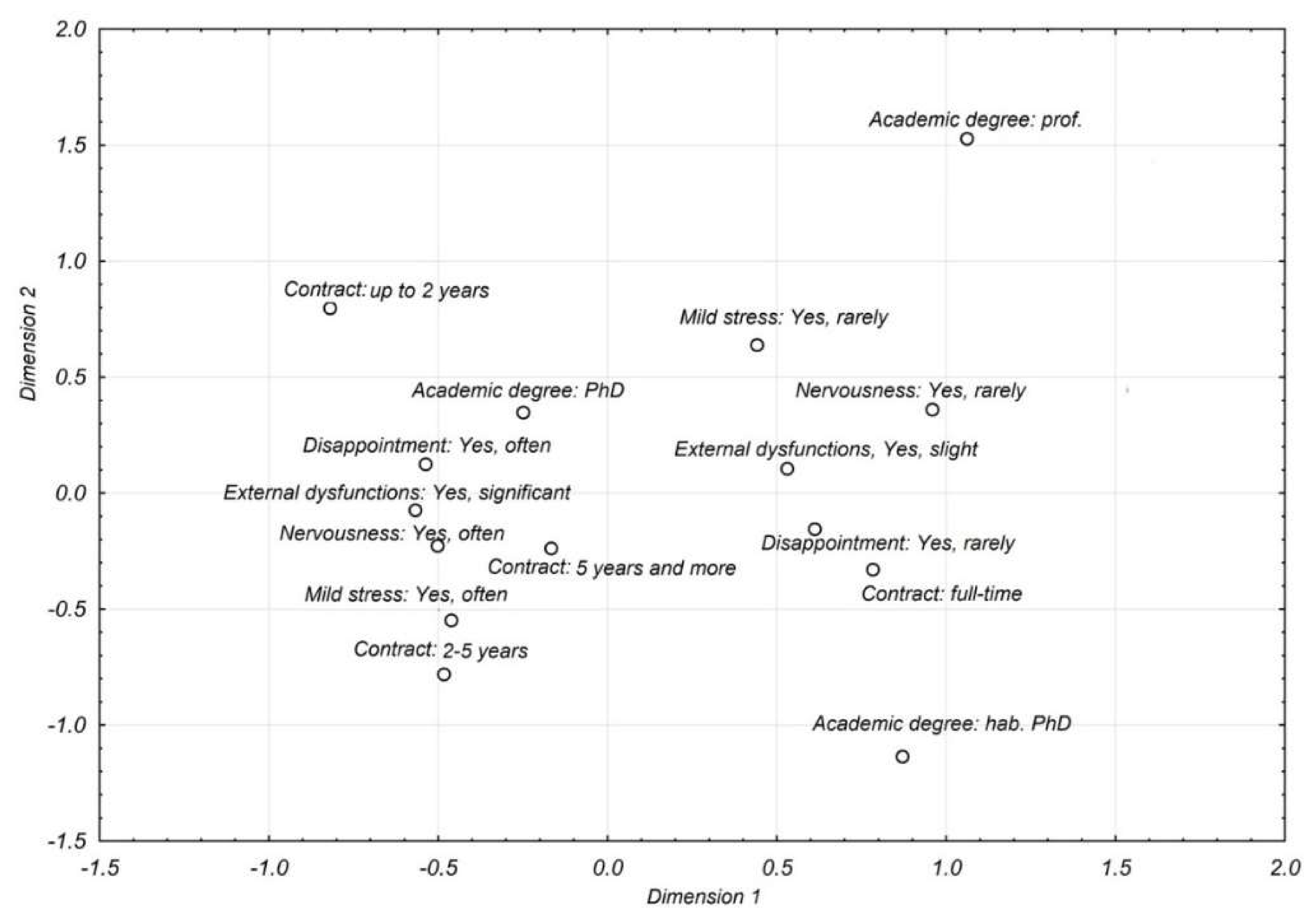

4. Results of Our Own Research

4.1. Stress Level in Scientific Procedures

4.2. Ailments and Dysfunctions Related to Participation in the Scientific Procedure

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- good, objective, and relevant assessment system,

- support from staff,

- relevant remuneration, liquidation of short-term contracts,

- improvement of work-life balance,

- psychological help from doctors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pop-Vasileva, A.; Baird, K.; Blair, B. University corporatisation: The effect on academic work-related attitudes. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2011, 24, 408–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taberner, A.M. The marketisation of the English higher education sector and its impact on academic staff and the nature of their work. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2018, 26, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, E.J.; Whitty, S.J. A model of projects as a source of stress at work: A case for scenario-based education and training. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 13, 426–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. University academics’ psychological contracts and their fulfilment. J. Manag. Dev. 2010, 29, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, C.; Churchman, D. Sustaining academic life: A case for applying principles of social sustainability to the academic profession. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoll, X.; Ramos, R. Quality of work, economic crisis, and temporary employment. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vereycken, A.Y.; Kort, L.D.; Vanhootegem, G.; Dessers, E. Care living labs’ effect on care organization and quality of working life. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2019, 32, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamija, P.; Gupta, S.; Bag, S. Measuring of job satisfaction: The use of quality of work life factors. Benchmarking 2019, 26, 871–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarayalu, A.V.; Al Kuwaiti, A. Quality of work life (QoWL) of faculty members in Saudi higher education institutions: A comparison between undergraduate medical and engineering program. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2019, 33, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaskoaga-Larrauri, J.; González-Laskibar, X.; Diaz-De-Basurto-Uraga, P.; Ignacio-Gómez, P. Why has there been a decrease in the job satisfaction of faculty at Spanish universities? Tert. Educ. Manag. 2015, 21, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, N.A.; Walsh, M.; Winefield, A.H.; Dua, J.; Stough, C. Occupational stress in universities: Staff perceptions of the causes, consequences and moderators of stress. Work Stress 2001, 15, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G. Pressure Points: A review of research on stressors and strains in UK academics. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Smith, A.P. Effects of occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and attributional style on the mental health and job satisfaction of university employees. Anxiety, Stress Coping 2012, 25, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.N.; Bush, R.F. Research Burnout in Tenured Marketing Professors: An Empirical Investigation. J. Mark. Educ. 1998, 20, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; Thomas, K.; Smith, A.P. Stress and Well-Being of University Staff: An Investigation Using the Demands-Resources- Individual Effects (DRIVE) Model and Well-Being Process Questionnaire (WPQ). Psychology 2017, 8, 1919–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moeller, C.; Chung-Yang, A. Effects of social support on professors’ work stress. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2013, 27, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwaiti, A.; Bicak, H.A.; Wahass, S. Factors predicting job satisfaction among faculty members of a Saudi higher education institution. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 12, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Caudle, D.J. Balancing academia and family life: The gendered strains and struggles between the UK and China compared. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacana, A.; Czerwińska, K.; Bednarowa, L. Comprehensive improvement of the surface quality of the diesel engine piston. Metalurgija 2018, 58, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Winefield, A.; Jarrett, R. Occupational Stress in University Staff. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2001, 8, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Smith, A. A Qualitative Study of Stress in University Staff. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2018, 5, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, S. Stress in Academic Life: The Mental Assembly Line; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Latack, J.C. Coping with job stress: Measures and future directions for scale development. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S. Towards better research on stress and coping. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohne, H. Stress and Coping Theories; Johannes Gutenberg-Universitat Mainz Germany: Mainz, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits, P.A. Stress and Health: Major Findings and Policy Implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, J. The psychosocial person. In Dimensions of Human Behavior; Person and Environment, 4th ed.; Hutchison, E.D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organisational Behaviour, 15th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seaward, B.L. Essentials of Managing Stress; Jones & Bartlett learning: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, P.A. The Job Satisfaction of English Academics and Their Intentions to Quit Academe; Discussion Paper; National Institute of Economic and Social Research: London, UK, 2005; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Teachers’ motivation for entering the teaching profession and their job satisfaction: A cross-cultural comparison of China and other countries. Learn. Environ. Res. 2014, 17, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, F.J.; Barry, A. Job satisfaction among academic staff: An international perspective. High. Educ. 1997, 34, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, S.; Kinman, G. Tackling Stress in Higher Education; University and College Union: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kinman, G.; Wray, S. Higher Stress. A Survey of Stress and Well-Being among Staff in Higher Education; University and College Union: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, C.; Cooper, C.L.; Ricketts, C. Occupational stress in UK higher education institutions: A comparative study of all staff categories. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2005, 24, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Chughtai, A.A.; Flood, B.; Willis, P. Job satisfaction among accounting and finance academics: Empirical evidence from Irish higher education institutions. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2012, 34, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G. Pressure Points: A Survey into the Causes and Consequences of Occupational Stress in UK Academic and Related Staff; AUT Publications: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, J.; Robertson, N. Burnout in university teaching staff: A systematic literature review. Educ. Res. 2011, 53, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minter, R.L. Faculty Burnout. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 2009, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyangwe, E. Recognising and Managing Stress in Academic Life, 2012. High Education Network Blog. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2012/jun/13/managing-academic-stress (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Simons, A.; Munnik, E.; Frantz, J.; Smith, M. The profile of occupational stress in a sample of health profession academics at a historically disadvantaged university in South Africa. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2019, 33, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wyllie, A.; Digiacomo, M.; Jackson, D.; Davidson, P.; Phillips, J.L. Acknowledging attributes that enable the career academic nurse to thrive in the tertiary education sector: A qualitative systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 62, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, M.; Macaskill, A.; Reidy, L. Stress among UK academics: Identifying who copes best. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opstrup, N.; Pihl-Thingvad, S. Stressing academia? Stress-as-offence-to-self at Danish universities. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2016, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packham, C.; Webster, S. Psychosocial Working Conditions in Britain in 2009; Health and Safety Executive: London, UK, 2009.

- Bexley, E.; Richard, J.; Arkoudis, S. The Australian Academic Profession in Transition: Addressing the Challenge of Reconceptualising Academic Work and Regenerating the Academic Workforce; Centre for the Study of Higher Education: Victoria, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos, E.; Palatsidi, V.; Tigani, X.; Darviri, C. Exploring stress levels, job satisfaction, and quality of life in a sample of police officers in Greece. Saf. Health Work 2014, 5, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alsaraireh, F.; Griffin, M.T.Q.; Ziehm, S.R.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. Job satisfaction and turnover intention among Jordanian nurses in psychiatric units. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, K.; Frost, L.; Hall, D. Predicting Teacher Anxiety, Depression, and Job Satisfaction. J. Teach. Learn. 2012, 8, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive Psychological Capital: Measurement and Relationship with Performance and Satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Emerging Positive Organizational Behavior. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, W.; Fu, J.; Chang, Y.; Wang, L. Epidemiological Study on Risk Factors for Anxiety Disorder among Chinese Doctors. J. Occup. Health 2012, 54, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Sun, T.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Luan, Y.-Z.; Fan, L. The relationship between job performance and perceived organizational support in faculty members at Chinese universities: A questionnaire survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zábrodská, K.; Jiří, M.; Iva, Š.; Petr, K.; Marek, B.; Kateřina, M. Burnout among university faculty: The central role of work–family conflict. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 38, 800–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torp, S.; Lysfjord, L.; Midje, H.H. Workaholism and work–family conflict among university academics. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 1071–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, C.M.; Borden, V.M.H. Faculty Service Loads and Gender: Are Women Taking Care of the Academic Family? Res. High. Educ. 2017, 58, 672–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunguz, S. In the eye of the beholder: Emotional labor in academia varies with tenure and gender. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ComRes. Teachers’ Satisfaction and Wellbeing in the Work Place: NASUWT. The Teacher’s Union. 2015. Available online: http://www.nasuwt.org.uk/consum/groups/public/@press/documents/nas_download/nasuwt_011847.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- YouGov. 2015. Available online: https://www.teachers.org.uk/node/24849 (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Mwangi, C.I. Emotional Intelligence Influence on Employee Engagement Sustainability in Kenyan Public Universities. Int. J. Acad. Res. Public Policy Gov. 2014, 1, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horta, H.; Cattaneo, M.; Meoli, M. PhD funding as a determinant of PhD and career research performance. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 43, 542–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J. Academic work and performativity. High. Educ. 2016, 74, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postiglione, G.A.; Jung, J. The Changing Academic Profession in Hong Kong; Springer: Gewerbestrasse, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seeber, M.; Lepori, B.; Montauti, M.; Enders, J.; De Boer, H.; Weyer, E.; Bleiklie, I.; Hope, K.; Michelsen, S.; Mathisen, G.N.; et al. European Universities as Complete Organizations? Understanding Identity, Hierarchy and Rationality in Public Organizations. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 1444–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.-R.; Du, J.-J.; Dong, R. Coping Style, Job Burnout and Mental Health of University Teachers of the Millennial Generation. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 3379–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newlon, K.; Lovell, E.D. Community College Student-Researchers’ Real Life Application: Stress, Energy Drinks, and Career Choices! Community Coll. J. Res. Pr. 2016, 41, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, D.; Costas, R.; Larivière, V. Misconduct Policies, Academic Culture and Career Stage, Not Gender or Pressures to Publish, Affect Scientific Integrity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bednarova, L.; Chovancová, J.; Pacana, A.; Ulewicz, R. The Analysis of Success Factors In Terms of Adaptation of Expatriates to Work in International Organizations. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 17, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H.; Pienaar, J.; De Cuyper, N. Review of 30 Years of Longitudinal Studies on the Association Between Job Insecurity and Health and Well-Being: Is There Causal Evidence? Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Rose, R.; Pilkington, A. Perceived Stress amongst University Academics. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2016, 6, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kinman, G. Doing More with Less? Work and Wellbeing in Academics. Somatechnics 2014, 4, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabo, F. Occupational stress among university employees in Botswana. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 15, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gorczynski, P.F.; Hill, D.; Rathod, S. Examining the Construct Validity of the Transtheoretical Model to Structure Workplace Physical Activity Interventions to Improve Mental Health in Academic Staff. EMS Commun. Med. J. 2017, 1, 002. [Google Scholar]

- Bleiklie, I.; Enders, J.; Lepori, B. (Eds.) Managing Universities: Policy and Organizational Change From a Western European Comparative Perspective; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. The knowledge economy and university workers. Austria Univ. Rev. 2015, 57, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H.; Postiglione, G.A.; Jung, J. Managerialism and the Academic Profession in Hong Kong. In The Changing Academic Profession in Hong Kong; Postiglione, G.A., Jung, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.-H. Higher Education Transformations for Global Competitiveness: Policy Responses, Social Consequences and Impact on the Academic Profession in Asia. High. Educ. Policy 2015, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. A Comparative Study of Occupational Stress in African American and White University Faculty; The Edwin Mellen Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, A.; Beverly, A. Beating Job Burnout; Harbor Publishing, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, M.P.; Abimbola, O.H. Job satisfaction, organizational stress and employee performance: A study of NAPIMS. IFE Psychol. IA Int. J. 2013, 21, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R.; Chiu, M.M. Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Peterson, S.J. The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2010, 21, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGonagle, A.K.; Beatty, J.E.; Joffe, R. Coaching for workers with chronic illness: Evaluating an intervention. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, R.; Audenaert, M.; Huisman, J.; Decramer, A. Performance management fairness and burnout: Implications for organizational citizenship behaviors. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 44, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.L.A.; Mas, M.B. Job stress and burnout syndrome at University: A descriptive analysis of the current situation and review of the principia lines of research. Ann. Clin. Health Psychol. 2010, 6, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera, N.; Rey, L. Burnout en profesionales de la ensenanza. un estudio en educacion primaria, secundaria y superior. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 17, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, M.C. Caracterizacion multivariante del sindrome de burnout en la plantilla docente de la Universidad de Salamanca. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, E. Analisis pormenorozado de los grados de burnout y tecnicas de afrontamiento del estres docente en profesorado universitario. Annales de Psicologia 2003, 19, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, J.M.; Avargues, M.L. Evaluacion del estres sociolaboral en el personal la Universidad de Sevilla. Rev. Mapfre Med. 2007, 18, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, D.; Carlos, R. El sindrome del quemado por estres laboral asistencial en grupos de docentes universitario. Revista de Investigacion en Psicologia 2005, 8, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, P.J.G.; Iersel-Van, V.; Silfhout, I.J. Job stress, job strain and psychological withdrwal amond Futch University Staff: Towards a dual proces model for the effects of ocupatinal stress. Work Stress 2001, 15, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.; Joseph, S. Burnout in University teaching Staff. Occup. Psychol. 1995, 27, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, S. Burnout and depression in academia: A look at the discourse of the university. Empedocles: Eur. J. Philos. Commun. 2015, 6, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatani, Y.; Nomura, K.; Horie, S.; Takemoto, K.; Takeuchi, M.; Sasamori, Y.; Takenoshita, S.; Murakami, A.; Hiraike, H.; Okinaga, H.; et al. Effects of gaps in priorities between ideal and real lives on psychological burnout among academic faculty members at a medical university in Japan: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lapointe, R.; Bhesania, S.; Tanner, T.; Peruri, A.; Mehta, P. An Innovative Approach to Improve Communication and Reduce Physician Stress and Burnout in a University Affiliated Residency Program. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- More Academics and Students Have Mental Health Problems than Ever Before, 2018. Theconversation. Available online: http://theconversation.com/more-academics-and-students-have-mental-health-problems-than-ever-before-90339 (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Guthrie, S.; Lichten, C.; Van Belle, J.; Ball, S.; Knack, A.; Hofman, J. Understanding Mental Health in the Research Environment: A Rapid Evidence Assessment; Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health in Academia: A Review of the Evidence, 2017. University of Bristol. Available online: http://www.bris.ac.uk/education/events/2017/mental-health-in-academia-a-review-of-the-evidence.html (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Shaw, C. Overworked and isolated—Work Pressure Fuels Mental Illness in Academia. Guardian. 8 May 2014. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2014/may/08/work-pressurefuels-academic-mental-illness-guardian-study-health (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Oleksiyenko, A. Zones of alienation in global higher education: Corporate abuse and leadership failures. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2018, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, N.; Tinline, G.; Robertson, I. Improving Performance through Wellbeing and Engagement: Wellbeing and Engagement Interventions Summary Report. 2011. Available online: http://www.ucea.ac.uk/download.cfm/docid/61E30F58-41EF-4332-A58F260C5ED90259 (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Shutler-Jones, K. Improving Performance through Well-Being and Engagement. Available online: http://www.qub.ac.uk/safety-reps/sr_webpages/safety_downloads/wellbeing-final-report-2011-web.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Pignata, S.; Boyd, C.; Gillespie, N.; Provis, C.; Winefield, A. Awareness of Stress-reduction Interventions: The Impact on Employees’ Well-being and Organizational Attitudes. Stress Health 2014, 32, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brems, C. A Yoga Stress Reduction Intervention for University Faculty, Staff, and Graduate Students. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2015, 25, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indelicato, N.A.; Mirsu-Paun, A.; Griffin, W.D. Outcomes of a Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training on a University Campus. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2011, 52, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koncz, R.; Wolfenden, F.; Hassed, C.; Chambers, R.; Cohen, J.; Glozier, N. Mindfulnessbased stress release program for university employees: A pilot, waitlist-controlled trial and implementation replication. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 58, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baruk, A.I. Polish University as an (UN) attractive potential employer. Mark. Sci. Res. Organ. 2017, 26, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Baruk, A. Postrzeganie uczelni jako pracodawcy przez młodych potencjalnych pracowników. Mark. Instytucji Naukowych i Badawczych 2016, 3, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R.; Mermelstein, T.K. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Cross, W.; Munro, I.; Jackson, D. Occupational stress facing nurse academics—A mixed-methods systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horta, H.; Jung, J.; Zhang, L.-F.; Postiglione, G.A. Academics’ job-related stress and institutional commitment in Hong Kong universities. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2019, 25, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, K.A.; Chakradhar, K.; Muller, S.; Waddill, P. Multigenerational perceptions of the academic work environment in higher education in the United States. High. Educ. 2014, 70, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontinha, R.; Van Laar, D.; Easton, S. Quality of working life of academics and researchers in the UK: The roles of contract type, tenure and university ranking. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 43, 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlangeli, O.; Guidi, S.; Marchigiani, E.; Bracci, M.; Liston, P.M. Perceptions of Work-Related Stress and Ethical Misconduct Amongst Non-tenured Researchers in Italy. Sci. Eng. Ethic- 2019, 26, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, N.J.; Williams, L. A quantitative study on organisational commitment and communication satisfaction of professional staff at a master’s institution in the United States. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2017, 39, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. Teacher–researcher role conflict and burnout among Chinese university teachers: A job demand-resources model perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 44, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altfeld, S.; Kellmann, M. Are German Coaches Highly Exhausted? A Study of Differences in Personal and Environmental Factors. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2015, 10, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foley, C.; Murphy, M. Burnout in Irish teachers: Investigating the role of individual differences, work environment and coping factors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 50, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagaman, M.A.; Geiger, J.M.; Shockley, C.; Segal, E.A. The Role of Empathy in Burnout, Compassion Satisfaction, and Secondary Traumatic Stress among Social Workers. Soc. Work 2015, 60, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Definition |

|---|---|

| Latack (1986) [23] | Defines stress by explaining the components of dealing with stress:

|

| Lazarus (2000) [24] | Defines the term stress as being a complex and multidimensional negative emotion. Coping with stress can lead to the reduction of demands (internal and external). |

| Krohne (2002) [25] | States that external demands (stressors) and those experienced by the body (stress) can be placed into two categories:

|

| Thoits (2010) [26] | Stressors can have a substantial damaging effect on mental and physical health |

| Walsh (2011) [27] | Describes a stressor as “any biological process, emotion or thought”. It is the outcomes of demands on the body during experiences of fight or flight. |

| Robbins and Judge (2013) [28] | Stress is an unpleasant psychological process that may happen as a response to environmental pressures. |

| Luke Seaward (2016) [29] | Stress is any change experienced by the individual. |

| Factor | Actions |

|---|---|

| General |

|

| Management |

|

| Employment |

|

| Career |

|

| Teaching |

|

| The Level of Stress for a Scientific Procedure (on a Scale from 1 to 10) | Academic Degrees and a Title | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In General | PhD | Hab. PhD | Prof. | |

| Sample size (N) | 1019 | 626 | 298 | 95 |

| Arithmetic mean (xsr) | 6.28 | 6.39 | 6.63 | 4.44 |

| Standard deviation (SD) | 2.53 | 2.30 | 2.62 | 2.95 |

| Lower quartile Q1 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 |

| Median Q2 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 4.00 |

| Upper quartile Q3 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 9.00 | 6.00 |

| Dominant Do | 8.00 | 7.00 | 8.00 | 1.00 |

| Minimum (MIN) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Maximum (MAX) | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| Coefficient of variation (Vx) | 40.32 | 35.97 | 39.52 | 66.30 |

| Ailments Felt | PhD | hab. PhD | Prof. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild stress | 33.7% | 12.9% | 6.3% |

| Nervousness | 33.0% | 15.0% | 5.2% |

| Psychological ailments | 19.9% | 8.7% | 2.9% |

| Damage to the relations | 19.5% | 8.1% | 2.9% |

| Psychosomatic disorders | 17.8% | 8.8% | 2.2% |

| Disappointment | 16.3% | 6.2% | 2.1% |

| Cardiac incidents | 8.8% | 5.1% | 3.9% |

| Felling of superiority | 6.7% | 3.5% | 1.3% |

| Cancer | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| External dysfunctions | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Other | 6.3% | 2.5% | 0.8% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolniak, R.; Szromek, A.R. The Analysis of Stress and Negative Effects Connected with Scientific Work among Polish Researchers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125117

Wolniak R, Szromek AR. The Analysis of Stress and Negative Effects Connected with Scientific Work among Polish Researchers. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125117

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolniak, Radosław, and Adam R. Szromek. 2020. "The Analysis of Stress and Negative Effects Connected with Scientific Work among Polish Researchers" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125117