Socio-Economic Benefits Stemming from Bush Clearing and Restoration Projects Conducted in the D’Nyala Nature Reserve and Shongoane Village, Lephalale, South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Socio-Economic Benefits of Restoration Projects in South Africa

2. Methods

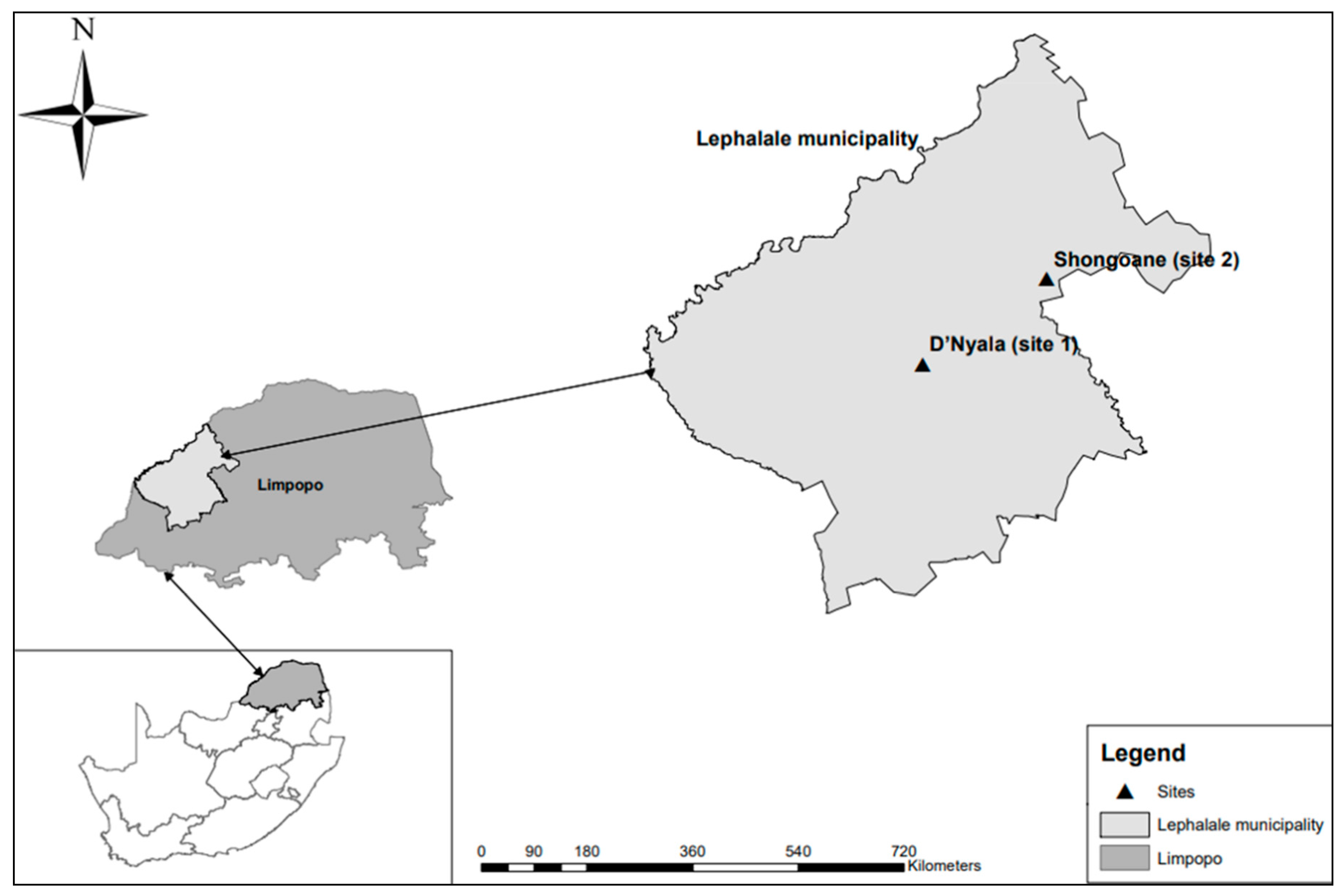

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Approach and Strategy

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure and Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Gathering

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Emerging Themes: D’Nyala Nature Reserve

3.1.1. Increase in Revenue

“There used to be a lot of bush even closer to the tar road, sometimes you could see the animal but when you try to get closer it would run and hide into the bush and it would be difficult to locate it.” Participant #1, 42

3.1.2. Reduction in Costs

“So far where it is cleared especially sickle bush, there is a visible change of vegetation of which is beneficial for the animals because there is more grass to graze.” Participant #3, 33

3.1.3. Employment Opportunities

“I am very happy because the project has employed many people from outside the nature reserve especially from the villages. At least month end the people can get something to buy food, half a loaf is better than nothing.” Participant #2, 56

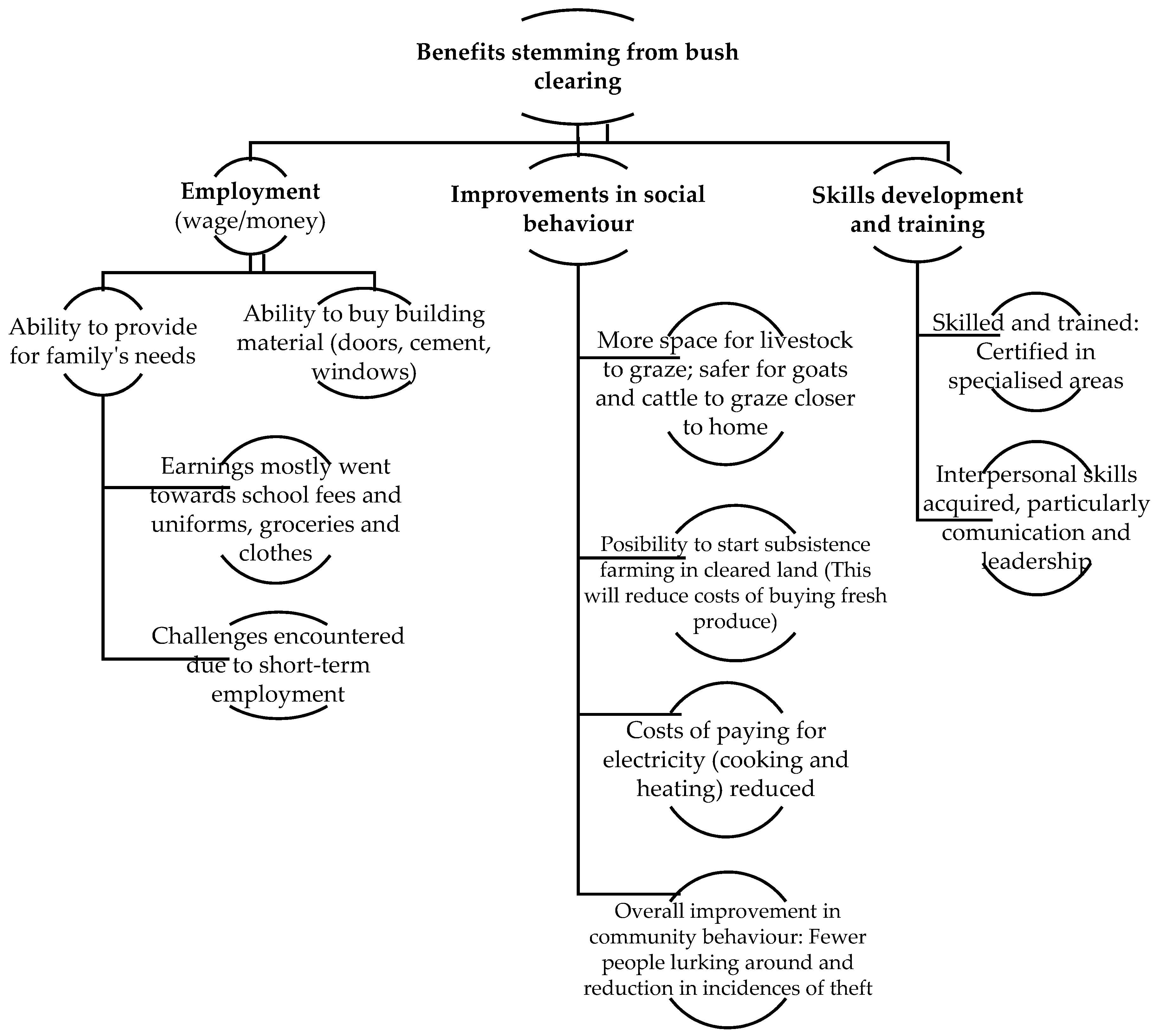

3.2. Emerging Themes: Shongoane Village

3.2.1. Employment

“This money has helped me because my husband is unemployed. We have a building project and the money has helped to buy doors and windows so that we can finish building the room.” Participant #8, 37

“Not much of my well-being has changed because the money is too little, I can only buy small things like groceries.” Participant #7, 31

3.2.2. Improvements in Social Behaviour

3.2.3. Skills Development and Training

“This project has not only benefited me, but others too because most people were unemployed in our village and now we are gaining experience.” Participant #5, 29

“We work well together and we listen to each other. If there is a problem, we solve it well without a fight.” Participant #5, 29

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Phillips, T.; Bonney, R. Citizen Science as a tool for conservation in residential ecosystems. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, G.M.; Norris, K.; Fitter, A.H. Biodiversity and ecosystem services: A multilayered relationship. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorondel, T.; Arma, I.; Florian, V.; Rusu, M.; Posner, C.; Erban, S. Policy Report Concerning the Socio-Economic and Environmental Transformations in the Lower Danube Floodplain. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Stefan_Dorondel/publication/308886022_POLICY_REPORT_CONCERNING_THE_SOCIOECONOMIC_AND_ENVIRONMENTAL_TRANSFORMATIONS_IN_THE_LOWER_DANUBE_FLOODPLAIN/links/57f4827c08ae280dd0b74940/POLICY-REPORT-CONCERNING-THE-SOCIO-ECONOMIC-AND-ENVIRONMENTAL-TRANSFORMATIONS-IN-THE-LOWER-DANUBE-FLOODPLAIN.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Linking social and ecological systems for resilience and sustainability. Link Soc. Ecol. Syst. Manag. Pract. Soc. Mech. Build. Resil. 1998, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Meek, M.H.; Wells, C.; Tomalty, K.M.; Ashander, J.; Cole, E.M.; Gille, D.A.; Putman, B.J.; Rose, J.P.; Savoca, M.S.; Yamane, L.; et al. Fear of failure in conservation: The problem and potential solutions to aid conservation of extremely small populations. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 184, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelane, T.S.; Kerley, G.I.H.; Knight, M.H. Reflections on the relationships between communities and conservation areas of South Africa: The case of five South African national parks. Koedoe 2006, 49, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saayman, M.; Van der Merwe, P.; Saayman, A.; Mouton, M.E. The socio-economic impact of an urban park: The case of Wilderness National Park. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2009, 1, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcamo, J. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A Framework for Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; p. 245. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, T.M.; Mittermeier, R.A.; da Fonseca, G.A.; Gerlach, J.; Hoffmann, M.; Lamoreux, J.F.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Pilgrim, J.D.; Rodrigues, A.S. Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 2006, 313, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francis, G.; Edinger, R.; Becker, K. A Concept for Simultaneous Wasteland Reclamation, Fuel Production, and Socio-economic Development in Degraded Areas in India: Need, Potential and Perspectives of Jatropha Plantations. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2005; Volume 29, pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, J.S.; Koro-Ljungberg, M.; Bartels, W.L. Power and conflict in adaptive management: Analysing the discourse of riparian management on public lands. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCaro, D.A.; Stokes, M.K. Public participation and institutional fit: A social–psychological perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernhardt, E.S.; Sudduth, E.B.; Palmer, M.A.; Allan, J.D.; Meyer, J.L.; Alexander, G.; Follastad-Shah, J.; Hassett, B.; Jenkinson, R.; Lave, R.; et al. Restoring rivers one reach at a time: Results from a survey of US river restoration practitioners. Restor. Ecol. 2007, 15, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Druschke, C.G.; Hychka, K.C. Manager perspectives on communication and public engagement in ecological restoration project success. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reid, H. Ecosystem-and community-based adaptation: Learning from community-based natural resource management. Clim. Dev. 2016, 8, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, C.A.; Reo, N.J.; Turner, D.A.; Cook, J.; Dituri, F.; Fessell, B.; Jenkins, J.; Johnson, A.; Rakena, T.M.; Riley, C.; et al. “The river is us; the river is in our veins”: Re-defining river restoration in three Indigenous communities. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, J.O. Conservation and development projects in the Brazilian Amazon: Lessons from the Community Initiative Program in Rondônia. Environ. Manag. 2002, 29, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhar, S.; Januschke, K.; Kail, J.; Poppe, M.; Schmutz, S.; Hering, D.; Buijse, A.D. Evaluating good-practice cases for river restoration across Europe: Context, methodological framework, selected results and recommendations. Hydrobiologia 2016, 769, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vermaat, J.E.; Wagtendonk, A.J.; Brouwer, R.; Sheremet, O.; Ansink, E.; Brockhoff, T.; Plug, M.; Hellsten, S.; Aroviita, J.; Tylec, L.; et al. Assessing the societal benefits of river restoration using the ecosystem services approach. Hydrobiologia 2016, 769, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roy, M.B.; Roy, P.K.; Samal, N.R.; Mazumdar, A. Socio-economic valuations of wetland based occupations of lower gangetic basin through participatory approach. Environ. Nat. Resour. Res. 2012, 2, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M.; Kok, K.; Rothman, D.S. Participatory scenario construction in land use analysis: An insight into the experiences created by stakeholder involvement in the Northern Mediterranean. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougill, A.J.; Akanyang, L.; Perkins, J.; Eckardt, F.D.; Stringer, L.C.; Favretto, N.; Atlhopheng, J.; Mulale, K. Land use, rangeland degradation and ecological changes in the southern Kalahari, Botswana. Afr. J. Ecol. 2016, 54, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mokgotsi, R.O. Effects of Bush Encroachment Control in a Communal Managed Area in the Taung Region. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University, North West Province, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.K.; Gerber, P.J. Climate change and the growth of the livestock sector in developing countries. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2010, 15, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Enhancing crop yields in the developing countries through restoration of the soil organic carbon pool in agricultural lands. Land Degrad. Dev. 2006, 17, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D. Do we understand the causes of bush encroachment in African savannas? Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2005, 22, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, W.; Birch, C.; Etter, H.; Blanchard, R.; Mudavanhu, S.; Angelstam, P.; Blignaut, J.; Ferreira, L.; Marais, C. The economics of landscape restoration: Benefits of controlling bush encroachment and invasive plant species in South Africa and Namibia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M.; Hutton, J. People, parks and poverty: Political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mukheibir, P.; Sparks, D. Water Resource Management and Climate Change in South Africa: Visions, Driving Factors and Sustainable Development Indicators. In Report for Phase I of the Sustainable Development and Climate Change Project; Energy and Development Research Centre (EDRC): Univesity of Cape Town, South Africa, 2003; Available online: http://www.erc.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/119/Papers-pre2004/03Mukheibir-Sparks_Water_resource_management.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Donnenfeld, Z.; Crookes, C.; Hedden, S. A delicate balance: Water scarcity in South Africa. ISS S. Afr. Rep. 2018, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, T.; Ashwell, A. Nature Divided: Land Degradation in South Africa; University of Cape Town Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2001; Volume 43. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.; The Nine Provinces of South Africa. South Africa Gateway 2019. Available online: https://www.southafrica-info.com/land/nine-provinces-south-africa/text=Limpopo (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Gibson, D.J. Land Degradation in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Gauteng Province, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lukomska, N.; Quaas, M.F.; Baumgärtner, S. Bush encroachment control and risk management in semi-arid rangelands. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffman, M.T.; Todd, S. A national review of land degradation in South Africa: The influence of biophysical and socio-economic factors. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2000, 26, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, D.; Holden, P. Case Studies on Successful Southern African NRM Initiatives and Their Impacts on Poverty and Governance; Report for IUCN/USAID Frame: Pretoria, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, J.; Clewell, A.F.; Blignaut, J.N.; Milton, S.J. Ecological restoration: A new frontier for nature conservation and economics. J. Nat. Conserv. 2006, 14, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Integrated Development Plan (IDP). Available online: http://www.lephalale.gov.za/docs/SDBIP/Final%20IDP%202018-19.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Moon, K.; Brewer, T.D.; Januchowski-Hartley, S.R.; Adams, V.M.; Blackman, D.A. A guideline to improve qualitative social science publishing in ecology and conservation journals. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, N.J.; Thomson, O.P.; Stew, G. Ready for a paradigm shift? Part 1: Introducing the philosophy of qualitative research. Man. Ther. 2012, 17, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khagram, S.; Nicholas, K.A.; Bever, D.M.; Warren, J.; Richards, E.H.; Oleson, K.; Kitzes, J.; Katz, R.; Hwang, R.; Goldman, R.; et al. Thinking about knowing: Conceptual foundations for interdisciplinary environmental research. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammersley, M. The issue of quality in qualitative research. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2007, 30, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Waterfield, J. Making words count: The value of qualitative research. Physiother. Res. Int. 2004, 9, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, G.R. Thematic coding and categorizing. Anal. Qual. Data Lond. Sage 2007, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Klerk, J.N. Bush Encroachment in Namibia. In Rep Phase 1 of the Bush Encroachment Research, Monitoring and Management Project; Ministry of Environment and Tourism: Windhoek, Namibia, 2004; p. 253. Available online: http://dasnamibia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/De-Klerk-Bush-Encoachment-in-Namibia-2004.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2019).

- Arbieu, U.; Grünewald, C.; Schleuning, M.; Böhning-Gaese, K. The importance of vegetation density for tourists’ wildlife viewing experience and satisfaction in African savannah ecosystems. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gcabo, R.P.E. Money and Power in Household Management: Experiences of Black South African Women. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Gauteng Province, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Posel, D.R. Who are the heads of household, what do they do, and is the concept of headship useful? An analysis of headship in South Africa. Dev. South Afr. 2001, 18, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, J.S.; Kieti, D. Tourism and socio-economic development in developing countries: A case study of Mombasa Resort in Kenya. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topics | Questions |

|---|---|

| (1)Bush clearing programme’s main benefit | Can you please describe what the main benefit that you received was and how you used the provision from participating in the bush clearing project? What was your involvement directly or indirectly in the bush clearing and restoration project? |

| (2)Programme influences and the outcome | Can you describe how you experienced the programme: did it help in any way, or not at all? |

| (3)Possible lasting/sustainable impact of the bush clearing programme | (a) Shongoane participants: What changes, if any, have you seen in your well-being (included here are money for school fees, food and basic needs, etc.) as a result of participating in the bush clearing and restoration project? Is there anything that you gained from the project that will help you in future? Please describe if there are any. (b) D’Nyala participants: What changes, if any, have you seen in the nature reserve (included here are generating money, enhancing game/nature viewing, etc.) as a result of participating in the bush clearing and restoration project? |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mangani, T.; Coetzee, H.; Kellner, K.; Chirima, G. Socio-Economic Benefits Stemming from Bush Clearing and Restoration Projects Conducted in the D’Nyala Nature Reserve and Shongoane Village, Lephalale, South Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125133

Mangani T, Coetzee H, Kellner K, Chirima G. Socio-Economic Benefits Stemming from Bush Clearing and Restoration Projects Conducted in the D’Nyala Nature Reserve and Shongoane Village, Lephalale, South Africa. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125133

Chicago/Turabian StyleMangani, Tshepiso, Hendri Coetzee, Klaus Kellner, and George Chirima. 2020. "Socio-Economic Benefits Stemming from Bush Clearing and Restoration Projects Conducted in the D’Nyala Nature Reserve and Shongoane Village, Lephalale, South Africa" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125133

APA StyleMangani, T., Coetzee, H., Kellner, K., & Chirima, G. (2020). Socio-Economic Benefits Stemming from Bush Clearing and Restoration Projects Conducted in the D’Nyala Nature Reserve and Shongoane Village, Lephalale, South Africa. Sustainability, 12(12), 5133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125133