Sharing Economy and Lifestyle Changes, as Exemplified by the Tourism Market

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Systematic Literature Review—Lifestyle, Sharing Economy and Peer-to-Peer Accommodation

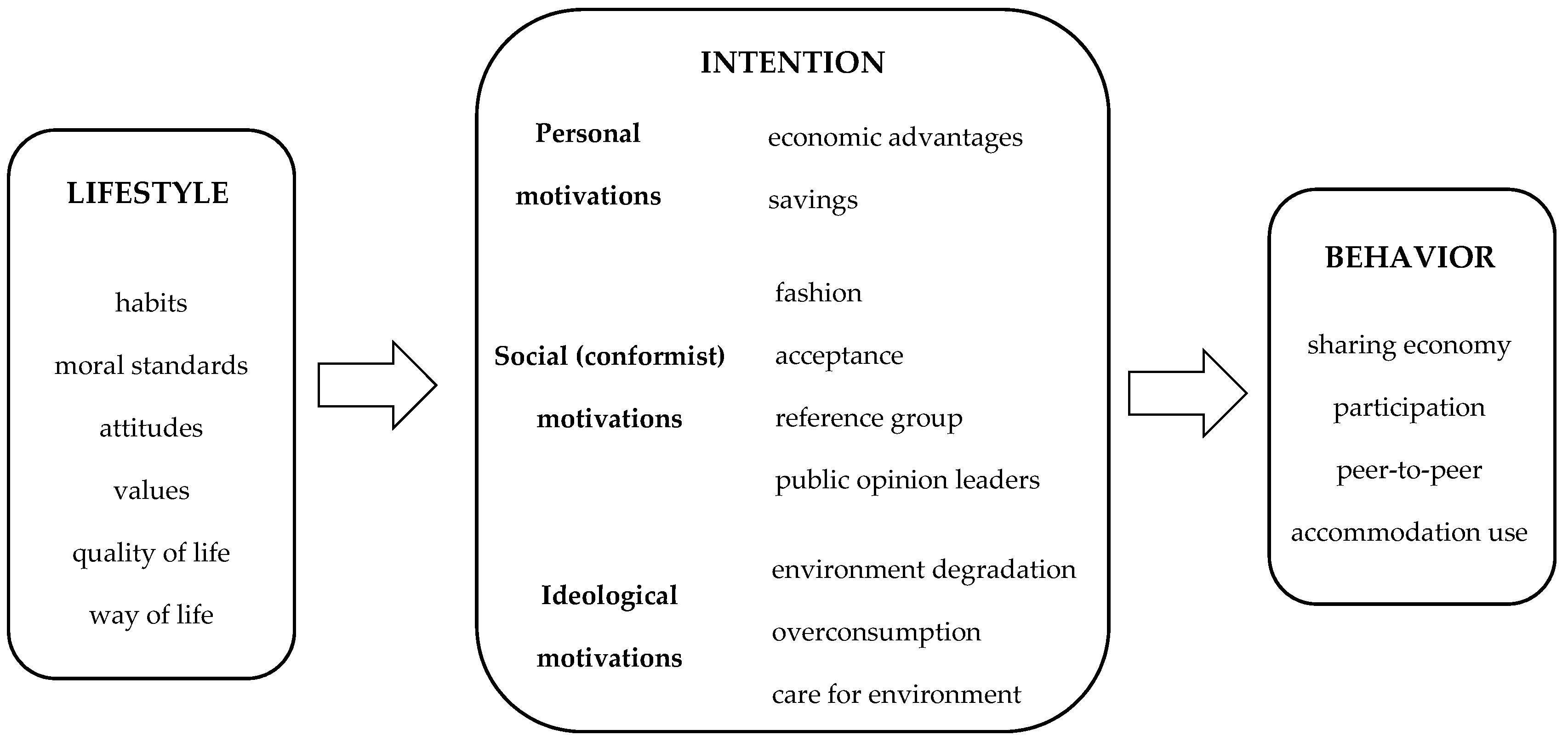

2.1. Lifestyle Changes and the Sharing Economy

2.2. Motivations for Activities Pertaining to the Sharing Economy

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results of the Empirical Study

4.1. Global Waste of Resources

4.2. Engaging in the Sharing Economy—Transportation, Food, Clothes, and Equipment

4.3. Travel Patterns, Peer-to-Peer Accommodation

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- The lack of a relationship between participation in the sharing economy and care for the environment is in contrast with some studies on motives for participating in the sharing economy in tourism and using peer-to-peer accommodation [16,24,61]. This could indicate that sharing economy business models may not be seen by consumers as sustainable or environmentally friendly. However, this finding does correspond to the economically and socially motivated behaviors reported in previous studies. Therefore, more attention should be paid to sustainability issues. Although the sharing economy model was conceived as an answer to over-consumption and the waste of resources, in reality, consumers pay more attention to financial and social benefits. By participating in sharing economy activities, they tend to contribute to reducing resource use in an unconscious and unintentional way.

- The results may be useful for companies that would like to operate according to a sustainable business model, which includes creating value for the customer in accordance with the principles of sustainable development. When constructing their own business models, companies should consider the overall lifestyle changes that characterize both groups of respondents (potential customers) and the importance of new customers’ preferences. These preferences should be taken into account in the creation of extended and potential components of business models, which may give a competitive advantage to traditional businesses in the tourism market (accommodation, transport, catering).

- The study shows differences between the two generations in terms of lifestyle, sense of responsibility for the use of resources, and motivations for participating in the sharing economy and for the specific organization of travel and use of peer-to-peer accommodation. In planning activities to promote sustainable consumption and sustainable business models, one should take these differences into account and highlight diverse lifestyle aspects in messages to both groups.

- The study was exploratory in nature and only included Polish respondents, but it should be noted that in the era of globalization, the needs and preferences of consumers may not necessarily differ between countries. People from both surveyed segments, YT and OR, can model their lifestyles on those found in other countries due to the frequency of travel and possibilities of communication using new technologies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Cheng, M.; Zhang, G. When Western hosts meet Eastern guests: Airbnb hosts’ experience with Chinese outbound tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 288–303.

- Guyader, H. No one rides for free! Three styles of collaborative consumption. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 692–714.

- Avdimiotis, S.; Poulaki, I. Airbnb impact and regulation issues through destination life cycle concept. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 13, 458–472.

- Lee, H.J. The effect of anti-consumption lifestyle on consumer’s attitude and purchase intention toward commercial sharing systems. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 1422–1441.

- Forno, F.; Garibaldi, R. Sharing Economy in Travel and Tourism: The Case of Home-Swapping in Italy. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 202–220.

- Nguyen, J.; Armisen, A.; Sánchez-Hernández, G.; Casabayó, M.; Agell, N. An OWA-based hierarchical clustering approach to understanding users’ lifestyles. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2020, 190, 1–26.

- Saturnino, R.; Sousa, H. Hosting as a Lifestyle: The Case of Airbnb Digital Platform and Lisbon Hosts. Partecip. E Conflitto 2019, 12, 794–818.

- Min, W.; Lu, L. Who Wants to Live Like a Local?: An Analysis of Determinants of Consumers’ Intention to Choose AirBNB. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering (ICMSE); IEEE, 2017; pp. 642–651.

- Alonso-Almeida, M. del M.; Perramon, J.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Shedding light on sharing ECONOMY and new materialist consumption: An empirical approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 1–9.

- Gierszewska, G.; Seretny, M. Sustainable Behavior—The Need of Change in Consumer and Business Attitudes and Behavior. Found. Manag. 2019, 11, 197–208.

- Penz, E.; Hartl, B.; Hofmann, E. Collectively Building a Sustainable Sharing Economy Based on Trust and Regulation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1–6.

- Cheng, M. Current sharing economy media discourse in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 60, 111–114.

References

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-Based Consumption: The Case of Car Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlmann, M. Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalska, T.; Markiewicz, E.; Pędzierski, M. Konsumpcja kolaboratywna w obszarze turystyki. Próba prezentacji stanu zjawiska na rynku polskim. Folia Tur. 2016, 41, 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Guyader, H. No one rides for free! Three styles of collaborative consumption. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 692–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- del Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Perramon, J.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Shedding light on sharing ECONOMY and new materialist consumption: An empirical approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böcker, L.; Meelen, T. Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansky, L. The Mesh—Why the Future of Business Is Sharing; Penguin: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780874216561. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J. The effect of anti-consumption lifestyle on consumer’s attitude and purchase intention toward commercial sharing systems. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 1422–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotko, E. Lifestyles in Modern Society and their Impact on the Market Behaviour of the Young Consumers. Ekon. Wrocław Econ. Rev. 2017, 23, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Patrzałek, W. The Determinants of Young Consumer’s Lifestyle. Mark. i Zarz. 2017, 2, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mihajlović, I.; Koncul, N. Changes in consumer behaviour—The challenges for providers of tourist services in the destination. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2016, 29, 914–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarmento, E.; Loureiro, S.; Martins, R. Foodservice tendencies and tourists’ lifestyle: New trends in tourism. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2017, 1, 2265–2277. [Google Scholar]

- Chon, K.S.; Pizam, A.; Mansfeld, Y. Consumer Behavior in Travel and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B. Consumer Behaviours on the Tourism Market. Econ. Probl. Tour. 2014, 4, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Forno, F.; Garibaldi, R. Sharing Economy in Travel and Tourism: The Case of Home-Swapping in Italy. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannisto, P. Travelling like locals: Market resistance in long-term travel. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, M.S.; Rangel, C.R.; Caldito, L.A. Analysis of spa tourist motivations: A segmentation approach based on discriminant analysis. Enl. Tour. A Pathmaking J. 2016, 6, 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daunorienė, A.; Drakšaitė, A.; Snieška, V.; Valodkienė, G. Evaluating Sustainability of Sharing Economy Business Models. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M.; Ruzzier, M.K. Transition towards sustainability: Adoption of eco-products among consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popovic, I.; Bossink, B.A.G.; van der Sijde, P.C. Factors influencing consumers’ decision to purchase food in environmentally friendly packaging: What do we know and where do we go from here? Sustainability 2019, 11, 7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Pesonen, J. Impacts of Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Use on Travel Patterns. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Pesonen, J. Drivers and barriers of peer-to-peer accommodation stay—An exploratory study with American and Finnish travellers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balck, B.; Cracau, D. Empirical analysis of customer motives in the shareconomy: A cross-sectoral comparison. Working Paper Series, University of Magdeburg. 2015. Available online: www.fww.ovgu.de/fww_media/femm/femm_2015/2015_02-EGOTEC-pfuspggp6m5tm4cr9hkm6h00i1.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Karlsson, L.; Dolnicar, S. Someone’s been sleeping in my bed. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlitschek, F.; Teubner, T.; Gimpel, H. Understanding the Sharing Economy—Drivers and Impediments for Participation in Peer-to-Peer Rental. In Proceedings of the 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; Volume 4801, pp. 4782–4791. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag, D.; Smith, S.; Potwarka, L.; Havitz, M. Why Tourists Choose Airbnb: A Motivation-Based Segmentation Study. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonides, G.; Van Raaij, W.F. Consumer Behaviour. A European Perspective; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek-Łopacińska, K.; Sobocińska, M. Virtualization of Marketing Communication in the Context of Population and Lifestyle Changes. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego. Probl. Zarządzania Finans. Mark. 2015, 39, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, E.; Arita, S.; Joung, S. Advancing sustainable consumption in Korea and Japan-from re-orientation of consumer behavior to civic actions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bywalec, C. Consumption in Economic Theory and Practice; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, B. Consumerism vs. sustainability: The emergence of new consumer trends in Poland. Int. J. Econ. Policy Emerg. Econ. 2010, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Micevski, M.; Dlacic, J.; Zabkar, V. Being engaged is a good thing: Understanding sustainable consumption behavior among young adults. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalega, T. Sustainable Consumption in Consumer. Stud. Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Katow. 2019, 82–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, C.T.; Hsieh, C.M.; Chang, H.P.; Chen, H.S. Environmental consciousness and green customer behavior: The moderating roles of incentive mechanisms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorenzen, J.A. Diderot Effect. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Consumption and Consumer Studies; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The rise of Collaborative Consumption; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-06-196354-4. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J. Understanding current and future issues in collaborative consumption: A four-stage Delphi study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akbar, Y.H.; Tracogna, A. The sharing economy and the future of the hotel industry: Transaction cost theory and platform economics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann Molz, J. Social networking technologies and the moral economy of alternative tourism: The case of couchsurfing.org. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Understanding repurchase intention of Airbnb consumers: Perceived authenticity, electronic word-of-mouth, and price sensitivity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Gyimóthy, S. The collaborative economy and tourism: Critical perspectives, questionable claims and silenced voices. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 286–302. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, C.Y. Sharing economy and prospects in tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zhang, G. When Western hosts meet Eastern guests: Airbnb hosts’ experience with Chinese outbound tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saturnino, R.; Sousa, H. Hosting as a Lifestyle: The Case of Airbnb Digital Platform and Lisbon Hosts. Partecip. Confl. 2019, 12, 794–818. [Google Scholar]

- Min, W.; Lu, L. Who Wants to Live Like a Local?: An Analysis of Determinants of Consumers’ Intention to Choose AirBNB. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Management Science and Engineering (ICMSE), Guilin, China, 18–20 August 2017; pp. 642–651. [Google Scholar]

- Gierszewska, G.; Seretny, M. Sustainable Behavior—The Need of Change in Consumer and Business Attitudes and Behavior. Found. Manag. 2019, 11, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avdimiotis, S.; Poulaki, I. Airbnb impact and regulation issues through destination life cycle concept. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 13, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Armisen, A.; Sánchez-Hernández, G.; Casabayó, M.; Agell, N. An OWA-based hierarchical clustering approach to understanding users’ lifestyles. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 190, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, E.; Hartl, B.; Hofmann, E. Collectively Building a Sustainable Sharing Economy Based on Trust and Regulation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palos-Sanchez, P.R.; Correia, M.B. The collaborative economy based analysis of demand: Study of airbnb case in Spain and Portugal. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 13, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sung, E.; Kim, H.; Lee, D. Why do people consume and provide sharing economy accommodation?-A sustainability perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansourian, Y. Exploratory nature of, and uncertainty tolerance in, qualitative research. New Libr. World 2008, 109, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezgoda, A.; Markiewicz, E. Lifestyle and Ecological Awareness of Consumers in the Tourist Market—Relations, Conditions and Problems. Ekon. Wroc. Econ. Rev. 2017, 23, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Niezgoda, A. Wpływ mody na rozwój turystyki. In Współczesne Uwarunkowania i Problemy Rozwoju Turystyki; Pawlusiński, R., Ed.; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2013; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sztompka, P. Zaufanie. Fundament Społeczeństwa; Znak: Kraków, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. An Exploratory Study on Drivers and Deterrents of Collaborative Consumption in Travel. In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015, Lugano, Switzerland, 3–6 February 2015; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 817–830. [Google Scholar]

- Owyang, J.; Tran, C.; Silva, C. The Collaborative Economy: Products, Services, and Market Relationships Have Changed as Sharing Startups Impact Business Models. To Avoid Disruption, Companies Must Adopt the Collaborative Economy Value Chain; Altimeter: San Mateo, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rostek, A.; Zalega, T. Konsumpcja kolaboratywna wśród młodych polskich i amerykańskich konsumentów (cz. 1). Mark. Rynek 2015, 5, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Skalska, T. Sharing economy in the tourism market: Opportunities and threats. Kwart. Nauk. Uczel. Vistula 2017, 4, 248–260. [Google Scholar]

| Aim | Method | Overall Results | Lifestyle Context | Activity Type | Sharing Economy–Lifestyle Links | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The study investigated western Airbnb hosts’ experiences with Chinese outbound tourists (p. 288). | Four-stage analysis of hosts’ comments. Co-occurrence analysis using the Gephi software | The research highlighted the role that cultural differences and tradition play in guest–host encounters, and offered a theoretical framework on inter-cultural host–guest relationship that provides an initial understanding of this phenomenon. | Lifestyle in an intercultural context: western hosts–Chinese guests | Peer-to-peer accommodation | Not directly indicated. Differences in the represented lifestyles can affect the experiences of both hosts and guests in case of peer-to-peer accommodation. | [47] |

| The study examined the nuanced styles of collaborative consumption in relation to market-mediated access practices and socially mediated sharing practices (p. 692). | Observation, ethnographic interviews, and a netnographic study | The research identified three styles of collaborative consumption: communal (pro-social), consumerist (commercial), and opportunistic (exploitative). | Lifestyle as part of collaborative consumption styles | Ridesharing | Convenient and trendy lifestyle as a factor influencing the consumerist collaborative consumption style in ridesharing. | [4] |

| The study re-established the role of the Airbnb platform in contemporary tourist destination management (p. 458). | Critical approach to regulatory measures | The findings indicated that restrictions on Airbnb are often unfounded. This is due to preconceptions regarding the impact on traditional hotels and the preservation of local lifestyles, rather than specific and objective measurements of impact. | Local lifestyle at risk due to the sharing economy | Short-term rental accommodation | The sharing economy is falsely seen as a threat to the local lifestyle. Local identity and lifestyle should be protected from unregulated sharing economy development. | [51] |

| The study described anti-consumption lifestyles and the impact of such lifestyles on the acceptance of commercial sharing systems (CSS) (p. 1422). | Structural equation modeling (SEM) | The findings indicated that anti-consumption lifestyles consist of frugality, voluntary simplicity, environmental protection, small luxury and tightwadism, and that they differently influence consumers’ behaviors with respect to using commercial sharing systems. | Lifestyle as a major driver of commercial sharing system use | Car and accommodation sharing services | The use of commercial sharing systems results from different anti-consumption lifestyles. Lifestyle trends of reducing consumption have emerged with the growth of the sharing economy. | [9] |

| This paper presented the results of an in-depth study into Italian home-swappers and discussed their socio-economic profiles, motivations, and lifestyles (p. 202). | Self-administered online survey | The findings indicated that home-swapping is an alternative form of tourism which requires trust, open-mindedness, inventiveness, enthusiasm, and flexibility. | Well-defined lifestyles as a driver of home-swapping | Home-swapping | In the case of the sharing economy (home-swapping), there is an overlap with other social practices present among niche consumers who are more concerned about the environment and more willing to respond to these concerns by changing their own lifestyle and consumption practices. | [16] |

| The study developed a method to understand users’ lifestyles based on their interactions with social networks (p. 1). | OWA (ordered weighted averaging) and hierarchical clustering | The selected partition for the Airbnb case defined a set of seven clusters. Six of them represented a different lifestyle. | Qualitative description of lifestyle | Dining in peer-to-peer accommodation (Airbnb) | Not directly indicated. The various lifestyle descriptions were determined based on characteristics obtained from comments from Airbnb accommodation users. | [52] |

| The study investigated how the sharing economy enables a digital platform to impact the way of life of Airbnb hosts (p. 794). | In-depth and semi-structured interviews | This shift in the sharing economy due to financial imperatives shows how much this field has been promoting the creation of new digital monopolies and the permanence of labor precariousness scenarios. People subject themselves to new forms of production that capitalize on their own intimacy. | Lifestyle changes as a result of being an Airbnb host | Peer-to-peer accommodation | Transforming the home into a commercial space forces hosts to adopt new social behaviors, and to acquire a new lifestyle. The contribution of hosting in the sharing economy is to challenge traditional social values. | [48] |

| The study explored the factors influencing consumer adoption of Airbnb. | Online survey | Performance expectancy, social influence, hedonic motivation, and price value are significant predictors of intention to use Airbnb. Consumers’ trust is positively related to performance expectancy. Consumers’ cross-cultural experience moderates the relationship between performance expectancy and behavior intention, and consumers’ extroversion. Change-seeking tendency moderates the relationship between hedonic motivation and behavior intention. | “Airbnb” as a new lifestyle | Short-term rental accommodation | The sharing economy appeals to those seeking change. Change-seeking refers to the demand for stimuli that a person needs to keep oneself in the best condition. It is a curiosity-motivated and variety-seeking behavior. Since Airbnb provides a lot of lodging types, change seekers are more likely to enjoy this feature. | [49] |

| The study identified a new consumer materialism within the sharing economy (p. 1). | Surveys collected during various events | Traditional materialism, i.e., the ownership and accumulation of goods, is losing its importance in favor of new materialism. Materialism is evolving from a mere static accumulation of goods towards a hybrid model (property and the enjoyment of goods coexist with the enjoyment of experience). | New materialism as a lifestyle | Sharing economy in general | The sharing economy can be a business model that will change consumers’ relationship to objects and the materialistic lifestyle. Changes in lifestyles caused by the economic crisis could lead to a reduction in the excessive consumption of goods and promote more responsible consumer behavior. | [5] |

| The study investigated the readiness of the young generation to face the challenge of changing their lifestyle based on unlimited consumption towards one that will take sustainability into account as a basis for consumer behavior (p. 179). | CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interview) method and online interviews | The quality of life, in the context of responsible development, requires a change in the way of thinking and philosophy of life, recognition of new values and lifestyles, and different shaping of living conditions. This includes changing consumer habits, which would contribute to changing lifestyles and thus reducing environmental damage. | Lifestyle results from consumption patterns | Freeganism (the reuse of food that has been thrown away or is to be thrown away) | Not directly indicated. Lifestyle results from consumer behavior. The method of consumption and striving for its rational dimension contribute to changing consumer habits and lifestyle, and to reducing environmental damage. The sharing economy can be the solution. | [50] |

| The study investigated how trust and regulation shape relations between providers and consumers in the sharing economy (p.1). | Literature review | Most sharing economy research is not focused on sustainability. Some areas of the sharing economy are conducive to sustainable development, others are conducive to social cohesion and ultimately build social capital, while still others focus on comfort and lifestyle. | Sustainable lifestyle | Sharing economy in general | Adopting a sustainable lifestyle can reduce the exploitation of natural resources. The sharing economy is part of a sustainable lifestyle—it offers and shares underutilized resources. | [53] |

| The study uncovered the theoretical foundations and key themes underlying the sharing economy. | Systematic literature review | There are three distinct areas within the sharing economy literature and two areas specific to tourism and hospitality: the sharing economy’s impact on destinations and tourism services, and the sharing economy’s impact on tourists. Five research streams were identified: lifestyle and social movement, consumption, sharing, trust, and innovation. | Lifestyle as one of the research streams | Sharing economy in general | The sharing economy has a strong intellectual tradition in the lifestyle and social movement field, consumption practices, and the sharing paradigm. Lifestyle is a primary means to foster social change. | [54] |

| Variable | Study |

|---|---|

| Cost savings, familiarity, trust, utility | [2] |

| Social appeal, economic appeal | [24] |

| Enjoyment, perceived network effect | [56] |

| Enjoyment, monetary benefits, accommodation amenities | [27] |

| Enjoyment, independence through ownership, modern lifestyle, social experience | [28] |

| Interaction, home benefits, novelty, sharing economy ethos, local authenticity | [29] |

| Activities | Motivations | |

|---|---|---|

| YT | OR | |

| Prevention of wasting resources | Ideological, personal | None |

| Fighting with environment pollution | Personal, ideological | Personal |

| Healthy eating | None | Personal, conformist |

| Attending “breakfast markets” | Personal | Personal, ideological |

| Using means of transport associated with the sharing economy | Personal, ideological | Personal |

| Swapping clothes | Personal, ideological | None |

| Renting equipment | Personal, ideological | None |

| Using peer-to-peer accommodation | Personal | Personal, conformist |

| Individual organization of holidays | Personal | Conformist |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niezgoda, A.; Kowalska, K. Sharing Economy and Lifestyle Changes, as Exemplified by the Tourism Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135351

Niezgoda A, Kowalska K. Sharing Economy and Lifestyle Changes, as Exemplified by the Tourism Market. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135351

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiezgoda, Agnieszka, and Klaudyna Kowalska. 2020. "Sharing Economy and Lifestyle Changes, as Exemplified by the Tourism Market" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135351

APA StyleNiezgoda, A., & Kowalska, K. (2020). Sharing Economy and Lifestyle Changes, as Exemplified by the Tourism Market. Sustainability, 12(13), 5351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135351