Public Bike Sharing Programs Under the Prism of Urban Planning Officials: The Case of Santiago de Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Overview of Bike Sharing in Chile

4. Materials and Methods

Focus Groups Conduction

5. Results

5.1. TA Coding Stage A

- Issues of empirical references (codes A1): Pertained to planning practitioners addressing their own experience in diverse real-life situations where PBSP have been implemented, along with other related situations, with regard to infrastructure conditions, challenges, and planning decisions altogether.

- Issues of critical reflection (codes A2): Related mainly to opinions and analyses, brought by planning practitioners while explaining and developing answers to questions that are prone to critical thinking.

- Issues of perception (codes A3): To explicitly provide opinions on matters with regard to both exposed empirical facts and critical analyses.

5.2. TA Coding Stage B

- Present infrastructure conditions and public space (B1 Codes): These codes sort all references to existing infrastructural conditions that enhance or neglect biking conditions in general and specially focused on the alteration of PBSP functioning—involving streets, walkways, parks highways, bikeways, metro stations, public transport lanes, etc.

- Present planning conditions (B2 Codes): These codes seek to retrieve issues related to existing planning conditions that directly or indirectly affect the implementation processes and existing PBSP, whether related to urban planning practice in general or highlighting particular ordinances and/or legal mechanisms related to such practices.

- Cultural adaptation processes (B3 Codes): These codes pertain to every process related to a change of conduct or conflicts of PBSP users, pedestrians, and users of other motorized and non-motorized transport modes altogether, for instance, the portrayal of conflicts between cars and bikes in the usage of street lanes, or problems between pedestrians and bikes in park areas.

- Perceptions on the implementation of PBSP (B4 Codes): These codes refer to matters of opinion regarding the present performance of the existing PBSP—to spot opinions on the use of existing PBSP coming from UPOs and how these are related to matters of perception of urban bettering or worsening, for instance.

5.3. TA Coding Stage C

5.4. Thematic Analysis Interrelations

- Progress perceptions brought by PBSP implementation (B1, B4)

- Infrastructural inequalities (B1, B2)

- Cultural assimilation and the use of PBSP (B2, B3)

in [the district of] Independencia we made a change in the local government [in relation to the recently elected major], the previous major was very unpopular, so all these things are perceived by people like improvements, like when the metro [Santiago´s underground network] arrived to the district. Thus, the arrival of BikeSantiago was like saying: look at what we were missing out… let´s imagine, an orange artifact came to our neighborhood, it was like saying “finally we are being considered” “someone is spoiling us”. (UPO testimony).

Most people understand that this “is what is coming”, the fact that there is an association with Paris or the Netherlands, people think that this is the right path, something like “Oh, it´s the same system of Paris. (UPO testimony).

- Infrastructural and cultural adaptation challenges (B1, B3)

- Beyond infrastructure and the role of planning in promoting a new biking conscience (B3-B4)

[T]he urban law [ordinance] is behind the bicycle, [and] to me this is the main reason behind the conflicts emerge either on roads, between cars and bicyclists, or in sidewalks, between cyclists and pedestrians. (UPO testimony).

- Mobility and accessibility planning needs at sight (B2, B3)

“The truth is that all factors and actors underline the difficulty to consolidate the necessary cycling infrastructure projects, and on top of this there is an anxiety on the part of urban planners of having little support from communities to implement cycling projects”

- Lacking planning partnerships (B2, B4)

- City governance (B2, B4)

5.5. Summary of Results and Pre-Theoretical implications

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Citylab. 2019. Available online: https://www.citylab.com/city-makers-connections/bike-share/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Faghih-Imani, A.; Eluru, N. Incorporating the impact of spatio-temporal interactions on bicycle sharing system demand: A case study of New York CitiBike system. J. Transport Geogr. 2016, 54, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, X. Bike-sharing systems and congestion: Evidence from US cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 65, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, T.L.; Wichman, C.J. Bicycle infrastructure and traffic congestion: Evidence of DC’s capital Bikeshare. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 87, 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Martin, E.; Cohen, A.P.; Finson, R. Public Bikesharing in North America: Early Operator and User Understanding; Mineta Transportation Institute: San Jose, CA, USA, 2012; Available online: http://transweb.sjsu.edu/PDFs/research/1029-public-bikesharingunderstanding-early-operators-users.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Woodcock, J.; Tainio, M.; Cheshire, J.; O’Brien, O.; Goodman, A. Health effects of the London bicycle sharing system: Health impact modelling study. BMJ 2014, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rueda, D.; de Nazelle, A.; Tainio, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. The health risks and benefits of cycling in urban environments compared with car use: Health impact assessment study. BMJ 2011, 343, d4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Guzman, S.; Zhang, H. Bikesharing in Europe, the Americas, and Asia: Past, present, and future. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 159–167. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6qg8q6ft (accessed on 10 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Vogel, M.; Hamon, R.; Lozenguez, G.; Merchez, L.; Abry, P.; Barnier, J.; Borgnat, P.; Flandrin, P.; Mallon, I.; Robardet, C. From bicycle sharing system movements to users: A typology of Vélo’v cyclists in Lyon based on large behavioral dataset. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 41, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Geneidy, A.; van Lierop, D.; Wasfi, R. Do people value bicycle sharing? A multilevel longitudinal analysis capturing the impact of bicycle sharing on residential sales in Montreal, Canada. Transp. Policy 2016, 51, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaio, P. Bike-sharing: History, impacts, models of provision, and future. J. Public Transp. 2009, 12, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslow, J.; Mont, O. Bicycle Sharing: Sustainable Value Creation and Institutionalisation Strategies in Barcelona. Sustainability 2019, 11, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.; Cai, H. Understanding bike sharing travel patterns: An analysis of trip data from eight cities. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kang, L.; Hsu, Y.; Wang, P. Exploring trip characteristics of bike-sharing system uses: Effects of land-use patterns and pricing scheme change. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Assi, W.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Habib, K.N. Effects of built environment and weather on bike sharing demand: A station level analysis of commercial bike sharing in Toronto. Transportation 2017, 44, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, X.; Tu, W.; Chen, Y.; Ratti, C. Unravel the landscape and pulses of cycling activities from a dockless bike-sharing system. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 75, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Akar, G. Gender gap generators for bike share ridership: Evidence from Citi Bike system in New York City. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-R.; Yang, T.-H. Strategic design of public bicycle sharing systems with service level constraints. Transp. Res. Part E 2011, 47, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frade, I.; Ribeiro, A. Bike-sharing stations: A maximal covering location approach. Transp. Res. Part A 2015, 82, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lamb, D.; Zhang, M.; Jia, P. Examining and optimizing the BCycle bike-sharing system—A pilot study in Colorado, US. Appl. Energy 2019, 247, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, I.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Rojas-Rueda, D. Health impacts of bike sharing systems in Europe. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E. Bikeshare: A Review of Recent Literature. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, R.; Smart, M. Bikeshare trip generation in New York City. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 94, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.B.; Brakewood, C. Sharing riders: How bikesharing impacts bus ridership in New York City. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 100, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Z. Improving Cycling Behaviors of Dockless Bike-Sharing Users Based on an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior and Credit-Based Supervision Policies in China. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z. Identifying the factors affecting bike-sharing usage and degree of satisfaction in Ningbo, China. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.; Usher, J. The role of bicycle-sharing in the city: Analysis of the Irish experience. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2015, 9, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathia, N.; Ahmed, S.; Capra, L. Measuring the impact of opening the London shared bicycle scheme to casual users. Transp. Res. Part C 2012, 22, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E.; Washington, S.; Haworth, N. Barriers and facilitators to public bicycle scheme use: A qualitative approach. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behavi. 2012, 15, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, A.; Charlemagne, M.; Xu, L. Data on public bicycle acceptance among Chinese university populations. Data Brief 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitas, A. How to Save Bike-Sharing: An Evidence-Based Survival Toolkit for Policy-Makers and Mobility Providers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizek, K.; Forsyth, A.C.; Slotterback, C. Is There a Role for Evidence-Based Practice in Urban Planning and Policy? Plan. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Sharing and Riding: How the Dockless Bike Sharing Scheme in China Shapes the City. Urban Sci. 2019, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Hernández, P.; Toro, F. Urban Systems of Accumulation: Half a Century of Chilean Neoliberal Urban Policies. Antípode 2019, 51, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.; Hodgson, F.; Mullen, C.; Timms, P. Creating inequality in accessibility: The relationships between public transport and social housing policy in deprived areas of Santiago de Chile. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 67, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.; Hurtubia, R. Vectores de expansión urbana y su interacción con los patrones socioeconómicos existentes en la ciudad de Santiago. EURE (Santiago) 2016, 42, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorf, A.; Hidalgo, R.; Sánchez, R. A new model of urban development in Latin America: The gated communities and fenced cities in the metropolitan areas of Santiago de Chile and Valparaíso. Cities 2007, 24, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.; Greene, M.; Mora, R. Efectos de las autopistas urbanas en sus entornos inmediatos: Un análisis desde la Sintaxis Espacial. Revista 2018, 180. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biblioteca de Sectra. Available online: http://www.sectra.gob.cl/biblioteca/detalle1.asp?mfn=3253 (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- La Tercera. 2018. Available online: https://www.latercera.com/opinion/noticia/bicicletas-publicas-santiago/105652/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Codeverde. 2019. Available online: http://codeverde.cl/santiago-es-la-segunda-ciudad-con-mas-viajes-en-bicicleta-en-latinoamerica/ (accessed on 10 July 2020). (In Spanish).

- Publimetro. 2019. Available online: https://www.publimetro.cl/cl/noticias/2019/03/04/mobike-santiago-centro-bicicletas-dos-millones.html (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Morse, J.M. Simultaneous and sequential qualitative mixed method designs. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhojailan, M.I. Thematic analysis: A critical review of its process and evaluation. West East J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A. Focussing in on focus groups: Effective participative tools or cheap fixes for land use policy? Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sanfuentes, M.; Garreton, M. Renegotiating roles in local governments: Facing resistances to citizen participation in Chile. Action Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F.; Cáceres, G. Segregación residencial en las principales ciudades chilenas: Tendencias de las tres últimas décadas y posi-bles cursos de acción. Rev. Eure 2001, 27, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, R.; Torres, A. Gated communities in Santiago: Wall or frontier? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, F. Modernisation, segregation and urban identities in the twenty-first century. Urbani Izziv 2011, 22, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L.; Mc Clure, O. The middle classes and the subjective representation of urban space in Santiago de Chile. Urban Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

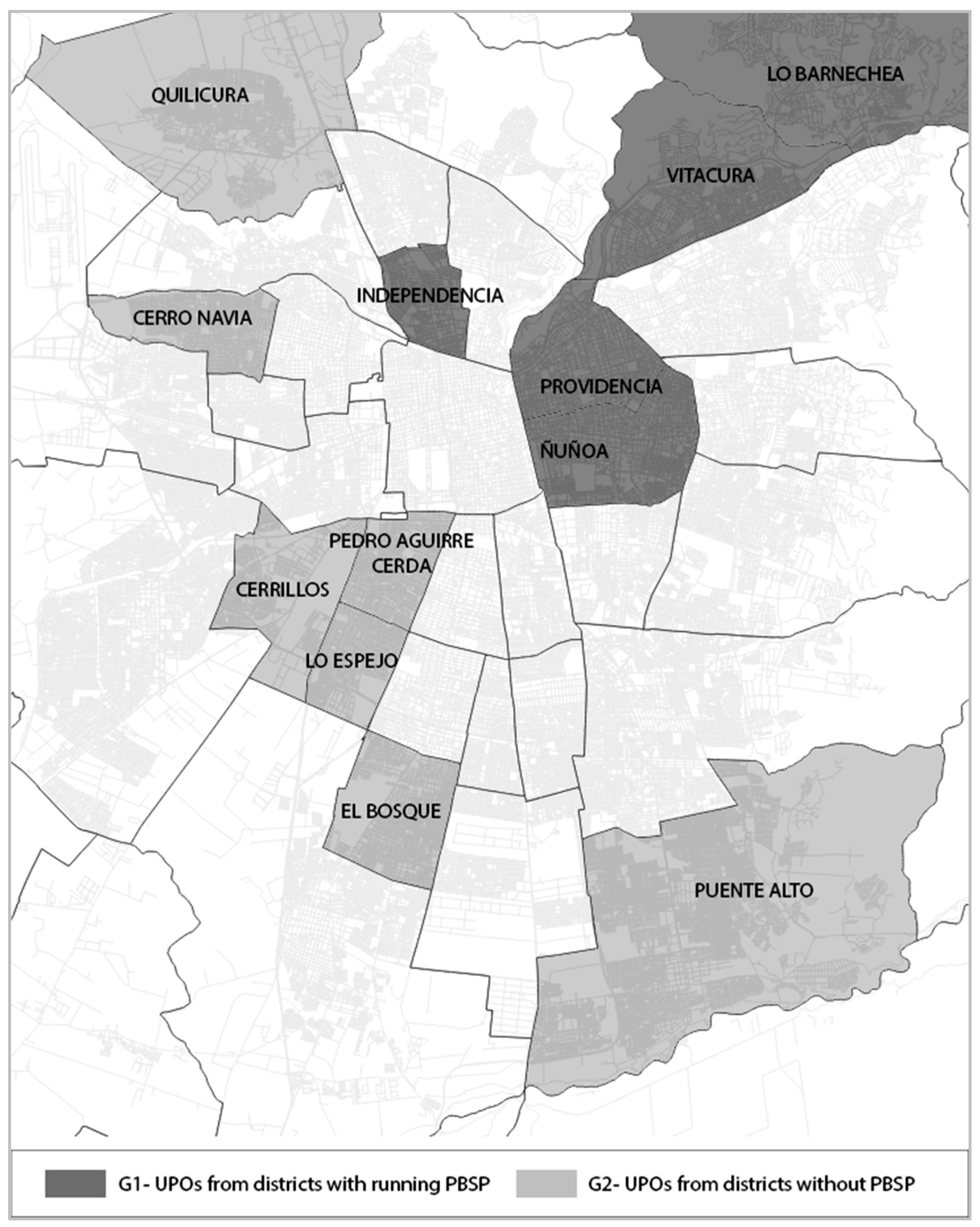

| Group name | Description | Group Size (N) | Common Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1-UPOs Group One | UPOs from local governments belonging to municipalities with running bike-sharing These municipalities are known as well-off districts also covering the area where most bike-sharing schemes operate in Santiago. | 7 participants | To understand the perception of bike-sharing schemes of those in charge of urban planning at district levels. |

| OK, thanksG2-UPOs Group Two | UPOs belong to municipalities without running bike-sharing schemes. These municipalities correspond to poor districts located in central and peripheral areas | 8 participants |

| District | Area | Population (2017 Census) | District’s SOCIOECONOMIC Profile | Presence of PBSP | Bike Lane Network (km) (2020) | Bike-Sharing Stations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitacura | 28 | 85,384 | High-income | Yes | 11.9 | 48 |

| Providencia | 14 | 142,079 | High income | Yes | 24 | 44 |

| Lo Barnechea | 1024 | 105,833 | High income | Yes | 0 | 15 |

| Ñuñoa | 17 | 208,237 | Middle-high income | Yes | 20.2 | 14 |

| Independencia | 7 | 100,281 | Middle-low income | Yes | 5.6 | 6 |

| Estación Central | 24 | 147.041 | Middle-low income | Yes | 10.8 | 3 |

| Quilicura | 58 | 210.410 | Low income | No | 6.5 | 0 |

| Cerro Navia | 11 | 132.622 | Low income | No | 2.7 | 0 |

| Puente Alto | 88 | 625,551 | Low income | No | 21.6 | 0 |

| Lo Espejo | 7 | 98,804 | Low income | No | 2.9 | 0 |

| Pudahuel | 197 | 230,293 | Low income | No | 2.9 | 0 |

| El Bosque | 14 | 162,505 | Low income | No | 5.9 | 0 |

| Cerrillos | 21 | 80.832 | Middle income | No | 4.6 | 0 |

| G1—TA —Stages A to B—UPOs in Municipalities with PBSP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A codes: data sorting | 88 total codes | B codes: data thematic categorisation | Intertwined B Codes: data reconstruction and crossed-referenced analysis | ||

| A1-empirical references A2-critical reflections A3-issues of perception | B1 Infrastructure | 23 codes | B1–B2—Interrelated infrastructure and planning conditions. | 6 intertwined codes | |

| B2 Planning | 33 codes | B2–B3—Planning concerns and cultural adaptation processes. | 5 intertwined codes | ||

| B3 Cultural adaptation | 23 codes | B1–B3—Infrastructural conditions portraying cultural adaptation processes. | 5 intertwined codes | ||

| B4 PBSP references | 17 codes | B2–B4—Planning concerns in the implementation and existing PBSP. | 5 intertwined codes | ||

| B1–B4—Infrastructure issues in the implementation and existing PBSP. | 7 intertwined codes | ||||

| B3–B4—Cultural adaptation processes in the implementation and existing PBSP. | 5 intertwined codes | ||||

| TA—Stages A to B—UPOs in Municipalities without PBSP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A codes: data sorting | B codes: data thematic categorisation | Intertwined B Codes: data reconstruction and crossed-referenced analysis | |||

| A1- empirical references A2-critical reflections A3-issues of perception | 94 total codes | B1 Infrastructure | 35 codes | B1-B2—Interrelated infrastructure and planning conditions. | 2 intertwined codes |

| B2 Planning | 22 codes | B2-B3—Planning concerns and cultural adaptation processes. | 4 intertwined codes | ||

| B3 Cultural adaptation | 22 codes | B1-B3—Infrastructural conditions portraying cultural adaptation processes. | 6 intertwined codes | ||

| B4 PBSP references | 23 codes | B2-B4—Planning concerns in the implementation and future PBSP. | 6 intertwined codes | ||

| B1-B4—Infrastructure issues in the implementation and existing PBSP. | 5 intertwined codes | ||||

| B3-B4—Cultural adaptation processes in the implementation and existing PBSP. | 5 intertwined codes | ||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mora, R.; Moran, P. Public Bike Sharing Programs Under the Prism of Urban Planning Officials: The Case of Santiago de Chile. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145720

Mora R, Moran P. Public Bike Sharing Programs Under the Prism of Urban Planning Officials: The Case of Santiago de Chile. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145720

Chicago/Turabian StyleMora, Rodrigo, and Pablo Moran. 2020. "Public Bike Sharing Programs Under the Prism of Urban Planning Officials: The Case of Santiago de Chile" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145720

APA StyleMora, R., & Moran, P. (2020). Public Bike Sharing Programs Under the Prism of Urban Planning Officials: The Case of Santiago de Chile. Sustainability, 12(14), 5720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145720