Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon

Abstract

1. Introduction

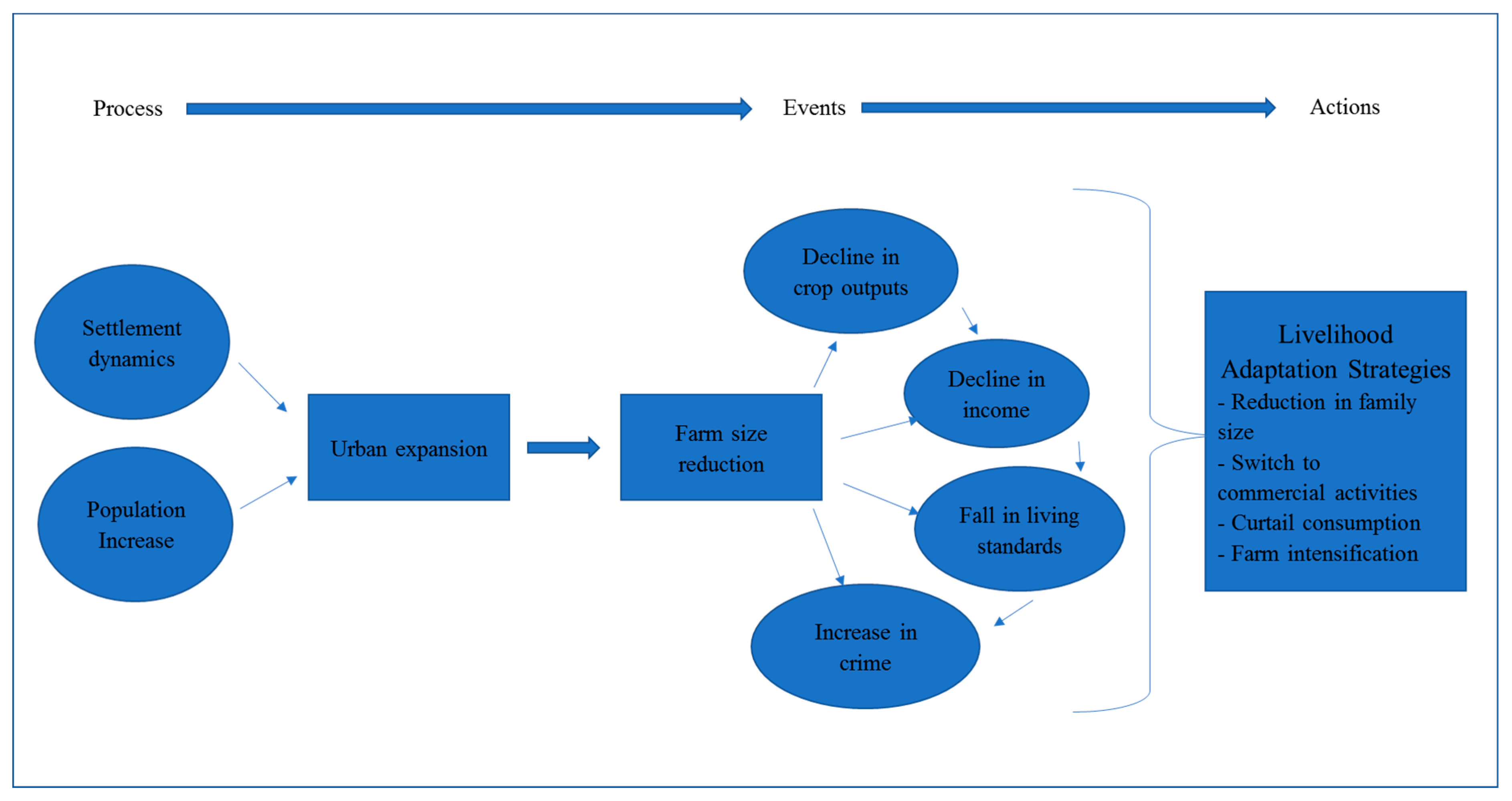

2. Analytical Lens

3. Materials and Methods

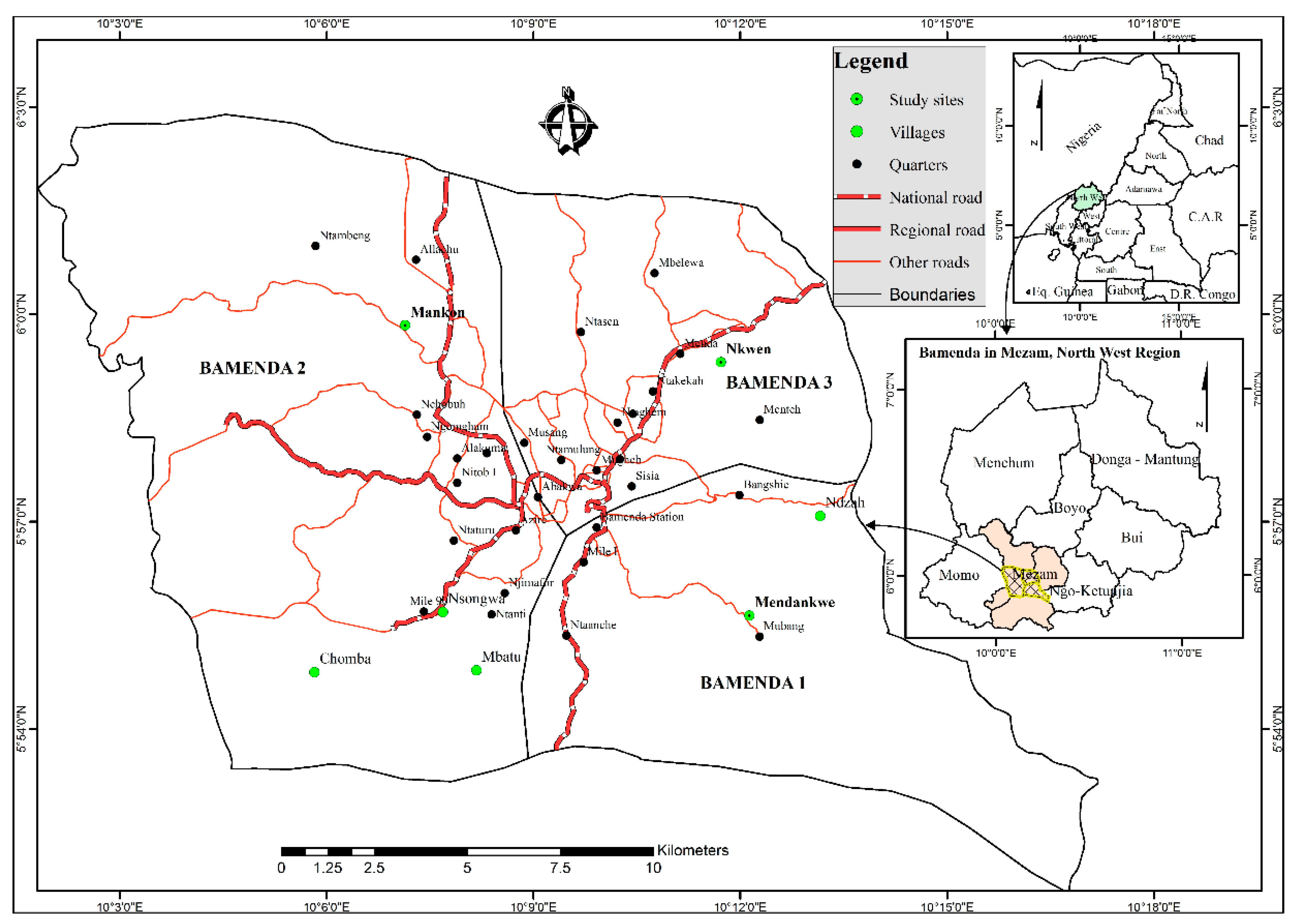

3.1. Study Area

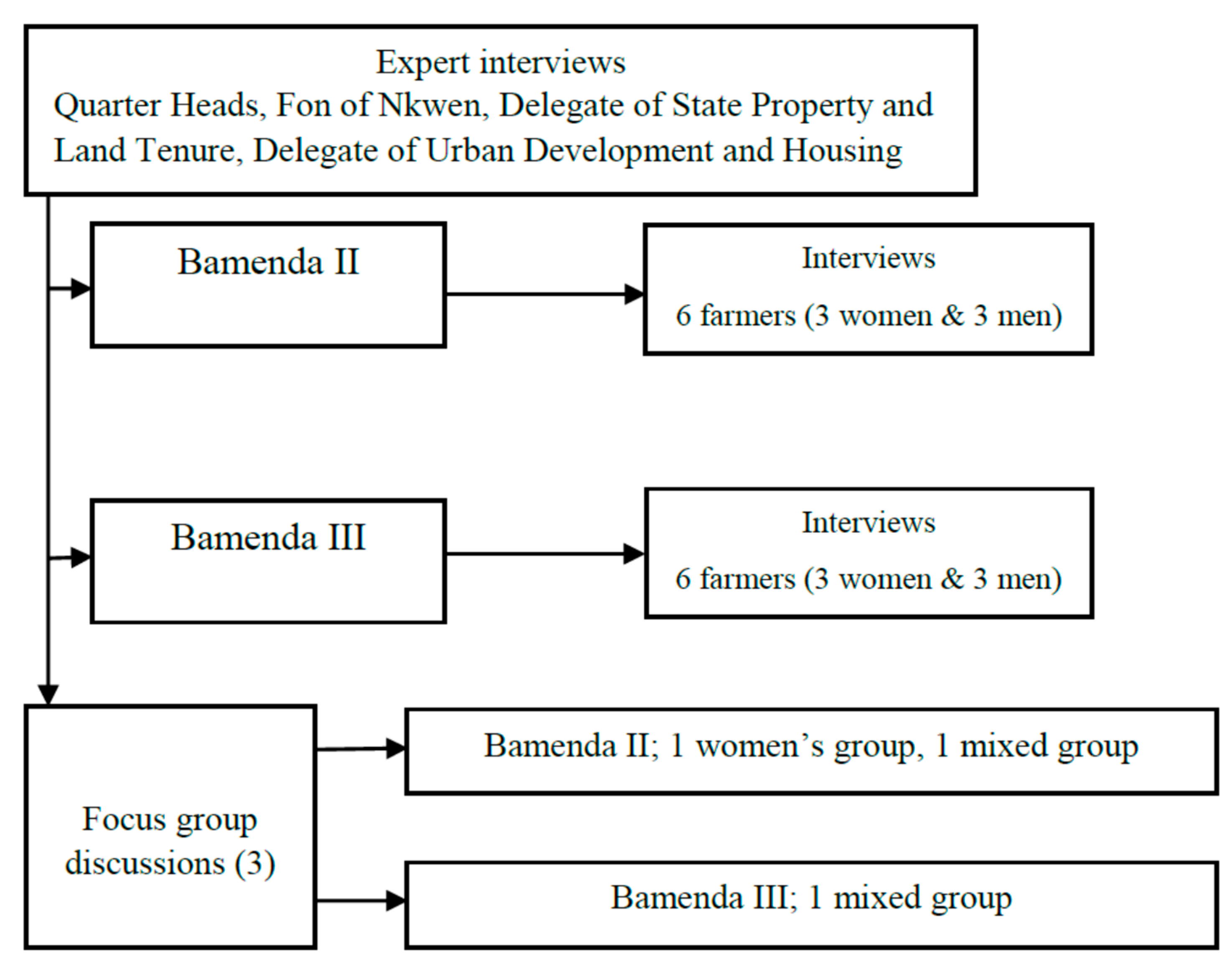

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

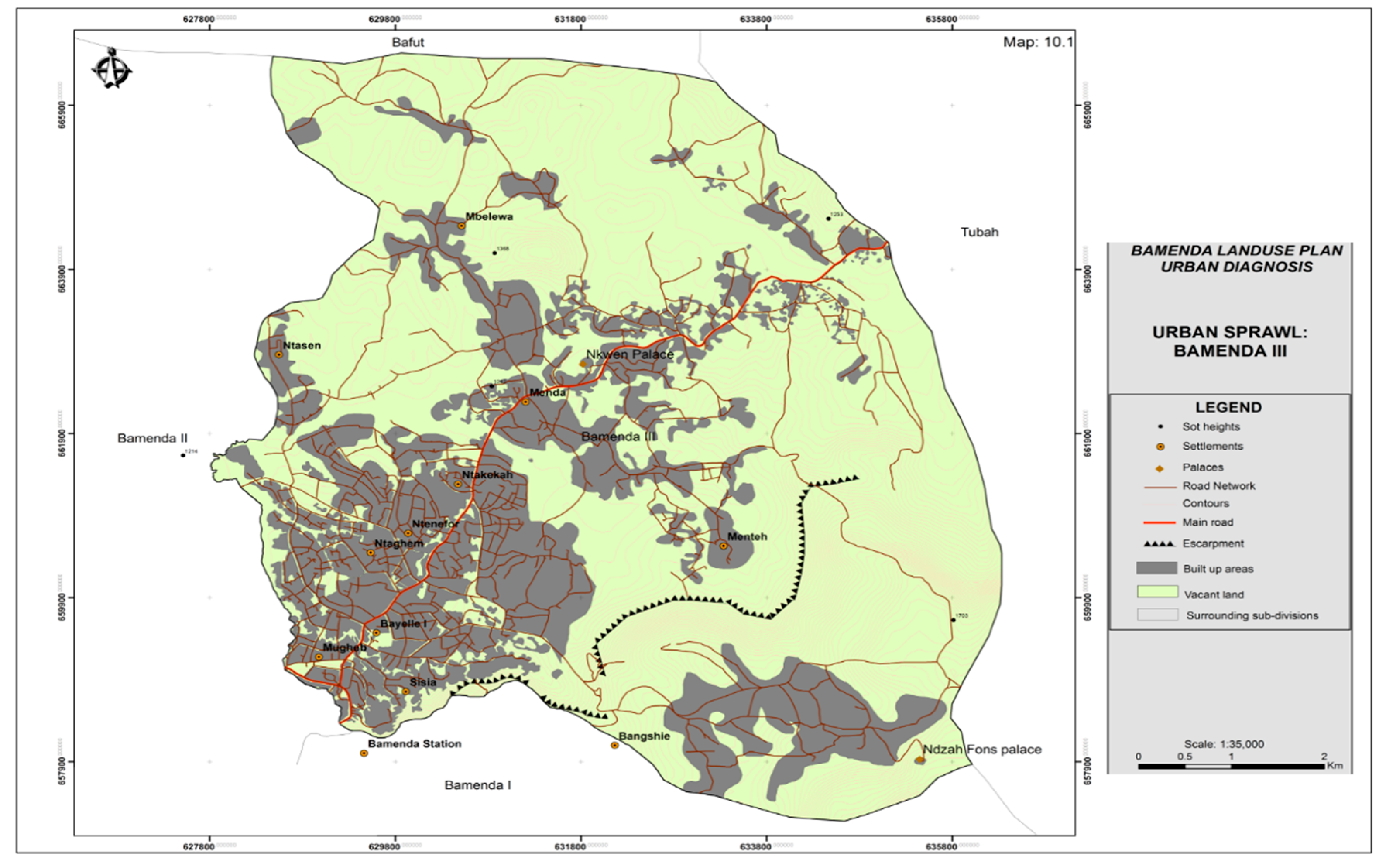

4.1. The Dynamics of Urban Expansion in Bamenda

4.2. Urban Expansion and Farmers’ Livelihood

I had friends that had been affected in one way or the other, but I really did not think it could come with strong implications not until I was faced with it. It was a nice thing for me to realize how development was being brought to us gradually through what you call urban expansion. Honestly, I never imagined that there was another side to it probably because I was not touched. I know roads and shops that were opened as more houses and offices were built in my area because of expansion of the city which was and still is a good thing.

4.3. Livelihoods Repertoire and Portfolio of Farmers before Urban Expansion

How much attention I gave to my farm? (Laughs). How can you ask a full-time farmer that? If I was not on the farm where else would I be? I did not even respect our traditional Sundays and that is how bad my own case was. Apart from Sunday which was my official off-farm-day, I was always on the farm. I only reduce farm going when my crops are at a stage where they do not need much attention. But it is so difficult not to find something to do on the farm.

…It is not only farming that puts food on my table or takes care of my family. … I am not saying that only farming is too menial for me to have achieved a good life, but I was lucky too to have some support from my brother abroad. He sent me money from time to time based on errands I ran for him back home.—Male respondent

Can I consider sponsorship and scholarship as part of income because my son earned a community scholarship that paid his fees every year also my last two children were sent to school every year by my sister’s husband? He sent money for their school fees and all other school needs every year.—Female respondent

In my own case I am or was not the only one that brought income to the family my wife also assisted a great deal. She did petit trading making snacks and selling them on campuses during lunch time and she was also a domestic servant for three families.—Male respondent

I had a large family then and they were really very supportive with very little exceptions. … There wasn’t any specific age for them to go or not go to the farm because we carry the very little ones to the farm as well and keep them under a tree for shade meanwhile, we work. When they eventually start walking, they try to do one of two things on the farm and we do not stop them in most cases and that is how they start embracing farming. Generally, they were all resourceful.

I would not say I was living in affluence then but what I got was sufficient for myself and my family… you can always say you are rich financially when you can afford comfortably the basic necessities of life. I equally was not living a hand to mouth life because money gotten from the sale of farm output could provide even for my saving. I mean it actually made up part of what I saved each month.

This idea was equally shared by majority of the respondents who said they considered or could rate their living condition as very comfortable. There was only one exception to this idea as the respondent said, “…I cannot actually tell you I was 100% fine because I still lived in debts back then, even though the situation is worse now.”

4.4. Livelihood Repertoire and Portfolio after Expansion

... and there is a lot of time on my hands now but nothing much to do I was so used to always going to the farm but now I do petit trading, that is, buying things from the city and selling them in interior markets on their market days which take place one a week.—one informant

Even though it does not add up to my income directly I can say that I was one person who was never regular at meeting sessions no had the time to participate in activities of the community but now that I have only one small farm, I am more active and dedicated.—one informant

... Yes of course if one loses his land and does not have where to farm, he must try to find an alternative means or activity to earn money. Alternatively, for me, I engaged in commercial motorbike riding during the weekends from Friday to Sunday I rent a bike and transport people. I learned how to ride a bike just as I was trying to find myself out of the challenges, I faced hopefully I can get my own bike one day.—Male respondent

It is very difficult for me to have coped without borrowing. At the beginning of every academic year I borrow money from a microfinance and spread payment within the year and if I have other commitments which come up, I borrow from family or friends (usually it is a small amount of money compared to what I take from the bank). Presently the yearly loan that I took from the bank I have stopped that because my business is growing fast and right now, I have grown past borrowing meagre amount I used to.—Male respondent

…It is very difficult for me to evaluate what assets I have because I have finally lost all of my cultivable land. But there are two things I can say I hang onto now which are my house (where I pay no rents) and my children or should I say family. When I say my family, I specifically refer to the strong and healthy who can do odd jobs to fend for the rest of the family… so, they are my assets.—Female respondent

… I had no option but to send five of my children to other relatives and family friends. I really do not regret this because they were the same people, I assisted at one point in life when I could. So, I do not think they took offence with this. At least none that I can think of right now.—Female respondent

5. Discussion

… urban expansion is evil and just a way to manipulate and marginalize the under privileged. You cannot disagree with me totally because I have had no visible good thing come out of all this. My farmland was taken away and I was promised compensation, but nothing has been given to me and it about 9 years today. My children left school and we sold almost all our property but ventured into the wrong business because I am not used to such investments. Most of you should know by now the reason why I lost my youngest son to hunger and malnutrition and my wife left me for another man because I could not provide for her anymore. I honestly did not have a name for all these until now that you can tell me it called urban expansion.

Yes, I received compensation for my land, and I am very grateful for that because some other women until today have not been paid even a little portion of the money. I was devastated at first but when I received the money, in two instalments, it was in time when I needed it. I had an opportunity to get a place into a professional school and the only issue was money. I sort for help for months and got nothing favorable and just when I was about to give up, I received a call that my name was amongst those to collect their money. So, I am now a teacher with the government, and I am assured of my monthly income and I can continue with farming because I have enough time. Had this not happened to me, I am sure I will not be able to get even a quarter of what I was expected to bring, or I will probably remain a farmer. …of course, I cannot compare my net income now to when I was a farmer. (Laughs) they are worlds apart.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muluken, D. An Assessment of the Impact of Urbanization on Peripheral Community Livelihood: Akaki kality Sub-City Case. Master’s Thesis, Ethiopian Civil Service College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Harmonious Cities: State of the World’s Cities 2008/2009; UN-Habitat: London, UK, 2009; Available online: www.clc.org.sg/pdf/UN-HABITAT20Report%20 (accessed on 30 August 2009).

- Araya, Y.H. Urban Land Use Change Analysis and Modelling: A Case Study of Setubal-Sesimbra, Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, NOVA University, Lisbon, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A.; da Silva, N.; Corubolo, E. Environmental Problems and Opportunities of the Peri- Urban. Interface and Their Impact Upon the Poor; Development Planning Unit, UCL: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, C.R.; Russwurm, L.H.; McLellan, A.G. The City’s Countryside: Land and its Management in the Rural-Urban Fringe; Longman: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ilbery, B.W. Agricultural specialization and farmer decision making in the West Midlands. Tijdschr. voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 1984, 75, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Gwan, S.A.; Elinge, L.E. Peri-Urban Settlement Dynamics in BUEA, Cameroon: Planning Challenges. UGEC Viewpoints: A Blog on Urbanization and Global Environmental Change. 2016. Available online: https://ugecviewpoints.wordpress.com (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- Organzation for Economic Cooperation. OECD Trends in Urbanisation and Urban Policies in OECD Countries: What Lessons for China? 2010. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/urban/roundtable/45159707.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2017).

- Bentinck, J. Unruly Urbanization on Delhi’s Fringe: Changing Patterns of Land Use and Livelihood. Utrecht/Groningen; The Netherlands Geographical Studies: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Nguh, B.S.; Nafoin, A.S. Peri-urban land use dynamics and development implications in the bamenda III municipality of Cameroon. Sustain. Environ. 2017, 2, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Fogwe, Z.N. Urban green development planning opportunities and challenges in sub-saharan Africa: Lessons from Bamenda city, Cameroon. Int. J. Glob. Sustain. 2017, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgah, S.N. Population growth and land use dynamics in Buea urban area, Cameroon. Loyola J. Soc. Sci. 2007, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Amawa, S.G.; Kimengsi, J.N. Accelerated Urbanisation in the Buea Municipality: The Question of Sustainability in the Provision of Social Services. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Cities, Cameroon, Yaounde, 10–13 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambod, E.M. Environmental consequences of rapid urbanisation: Bamenda city, Cameroon. J. Environ. Prot. 2010, 1, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kometa, S.S.; Akoh, N.R. The hydro-geomorphological implications of urbanisation in Bamenda, Cameroon. J. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgah, S.N.; Kimengsi, J.N. Land use dynamics and wetland management in Bamenda: Urban development policy implications. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgah, R.A.; Kimengsi, J.N. Can policy deviance reduce poverty? Empirical evidence from self-return environmental migrants in Cameroon. Soc. Sci. J. 2019, 69, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Mukong, A.K.; Balgah, R.A. Livelihood diversification and household well-being: Insights and policy implications for forest-based communities in Cameroon. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFID. Framework Introduction. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. 2000. Available online: http://www.eldis.org/go/topics/dossiers/livelihoods-connect/what-are-livelihoods-approaches/training-and-learningmaterials (accessed on 8 September 2016).

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tellis, W. Introduction to case study. Qual. Res. 1997, 3, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qual. Res. 2008, 8, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woiceshyn, J.; Daellenbach, U. Evaluating inductive vs deductive research in management studies. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 13, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, R.E.; Anderson, W.D. Development at the Urban Fringe and Beyond: Impacts on Agriculture and Rural Land; Agricultural Economic Report No. 803; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington DC, 2009; pp. 5–88.

- Andersson, A.; Djurfeldt, G. African smallholders-food crops, markets and technology. In Maize Remittances, Market Participation and Consumption Among Smallholders in Africa; Djurfeldt, G., Aryeetey, E., Isinika, A.C., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele, F. The Impact of Horizontal Urban Expansion on Sub-Urban Agricultural Community Livelihood: The Case of Tabor Sub-City, Hawassa City, SNNPRS, Ethiopia; Institute of Rural Development, College of Development Studies, School of Graduate Studies Addis Ababa University: Addis Ababa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Xin, L.; Hao, H. Geographic concentration and driving forces of agricultural land use in China. Front. Earth Sci. 2012, 6, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keliang, Z.; Prosterman, R. Securing land rights for Chinese farmers: A leap forward for stability and growth. Cato Dev. Policy Anal. Ser. 2007, 3, 20. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gwan, A.S.; Kimengsi, J.N. Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145788

Gwan AS, Kimengsi JN. Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145788

Chicago/Turabian StyleGwan, Akhere Solange, and Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi. 2020. "Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145788

APA StyleGwan, A. S., & Kimengsi, J. N. (2020). Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon. Sustainability, 12(14), 5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145788