Qualitative Study on Electricity Consumption of Urban and Rural Households in Chiang Rai, Thailand, with a Focus on Ownership and Use of Air Conditioners

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

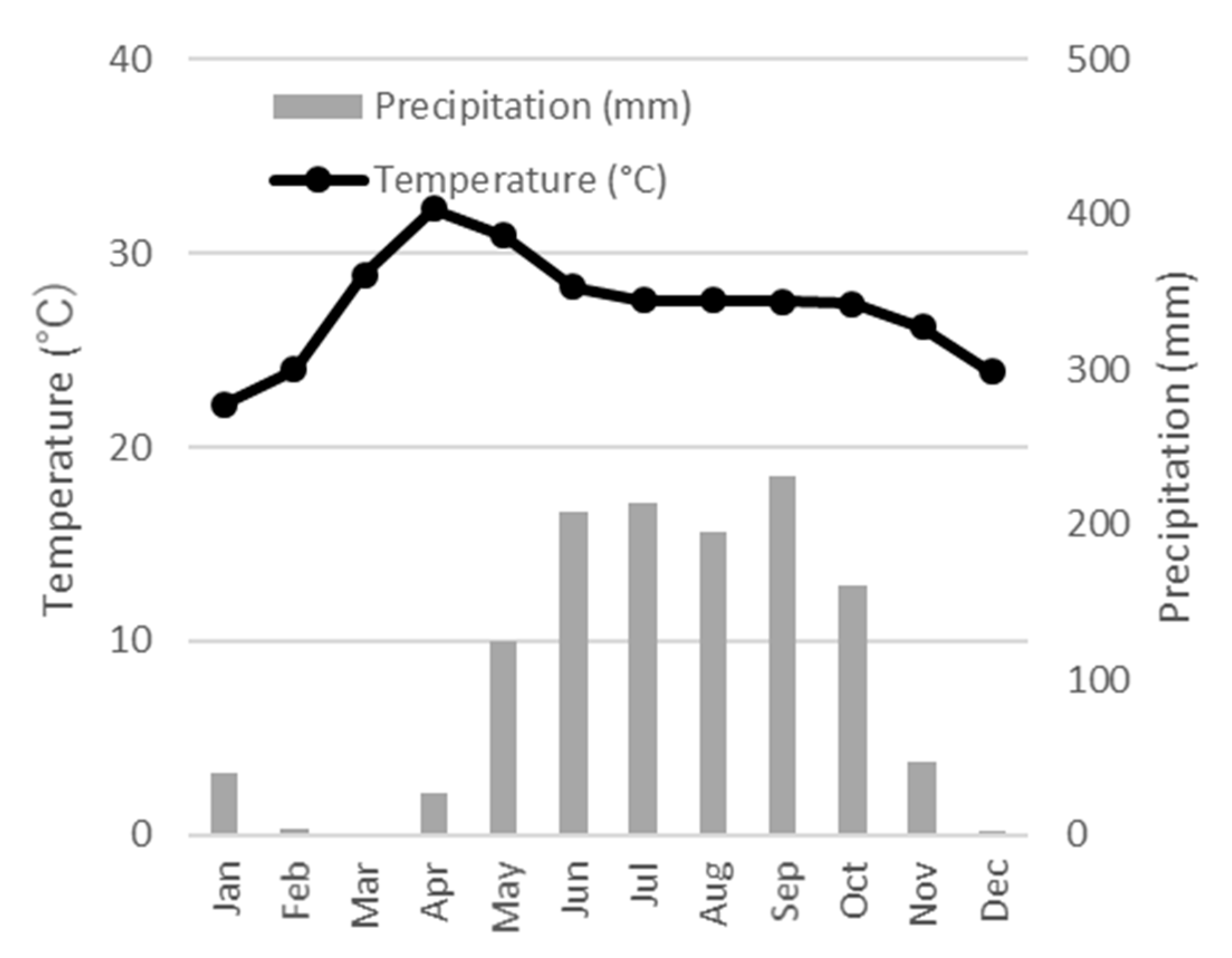

2.1. Survey Area

2.2. Household Survey

3. Results

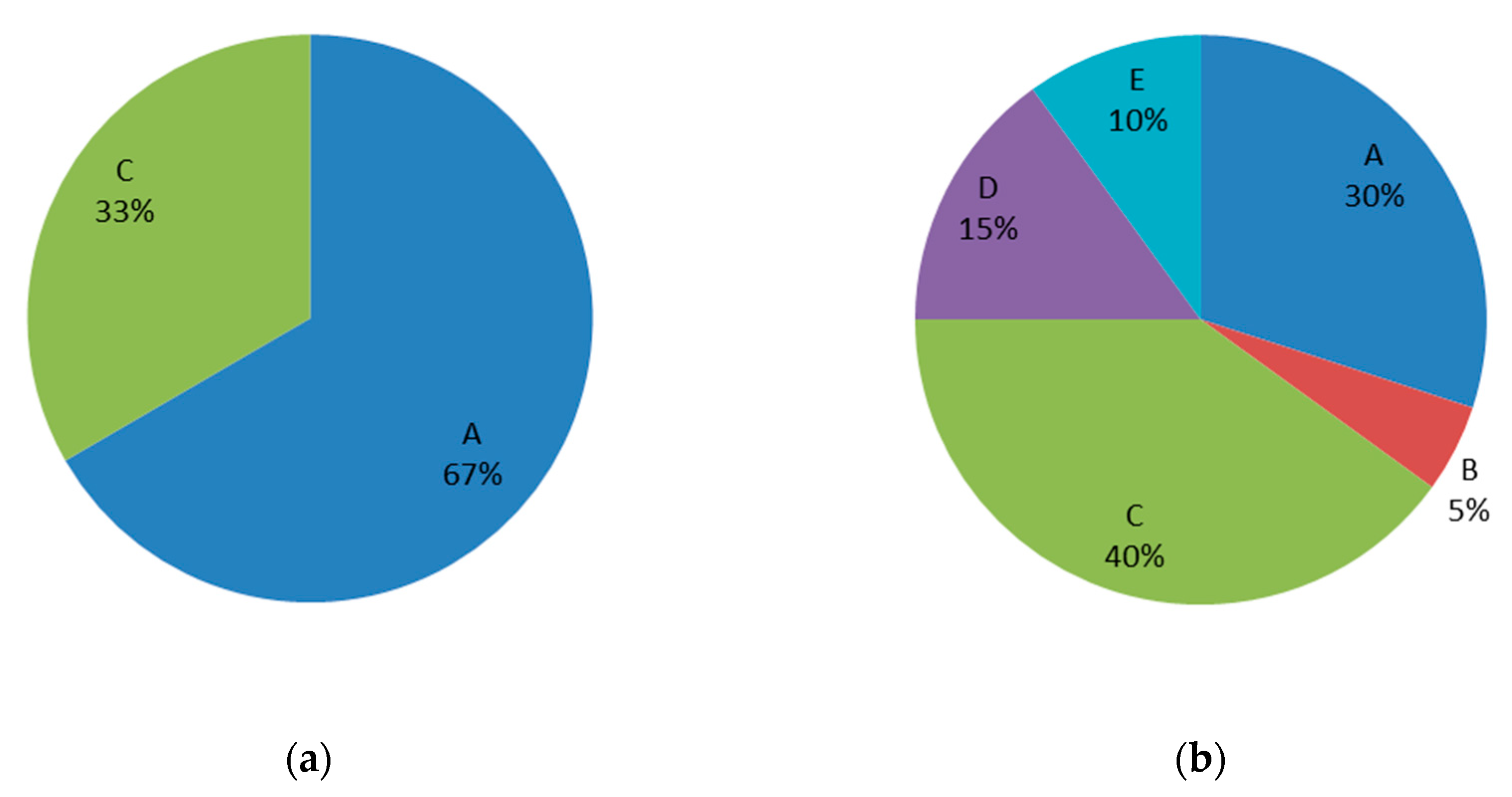

3.1. Household Characteristics

Subsubsection

3.2. Housing Characteristics

3.3. Ownership of Electric Devices

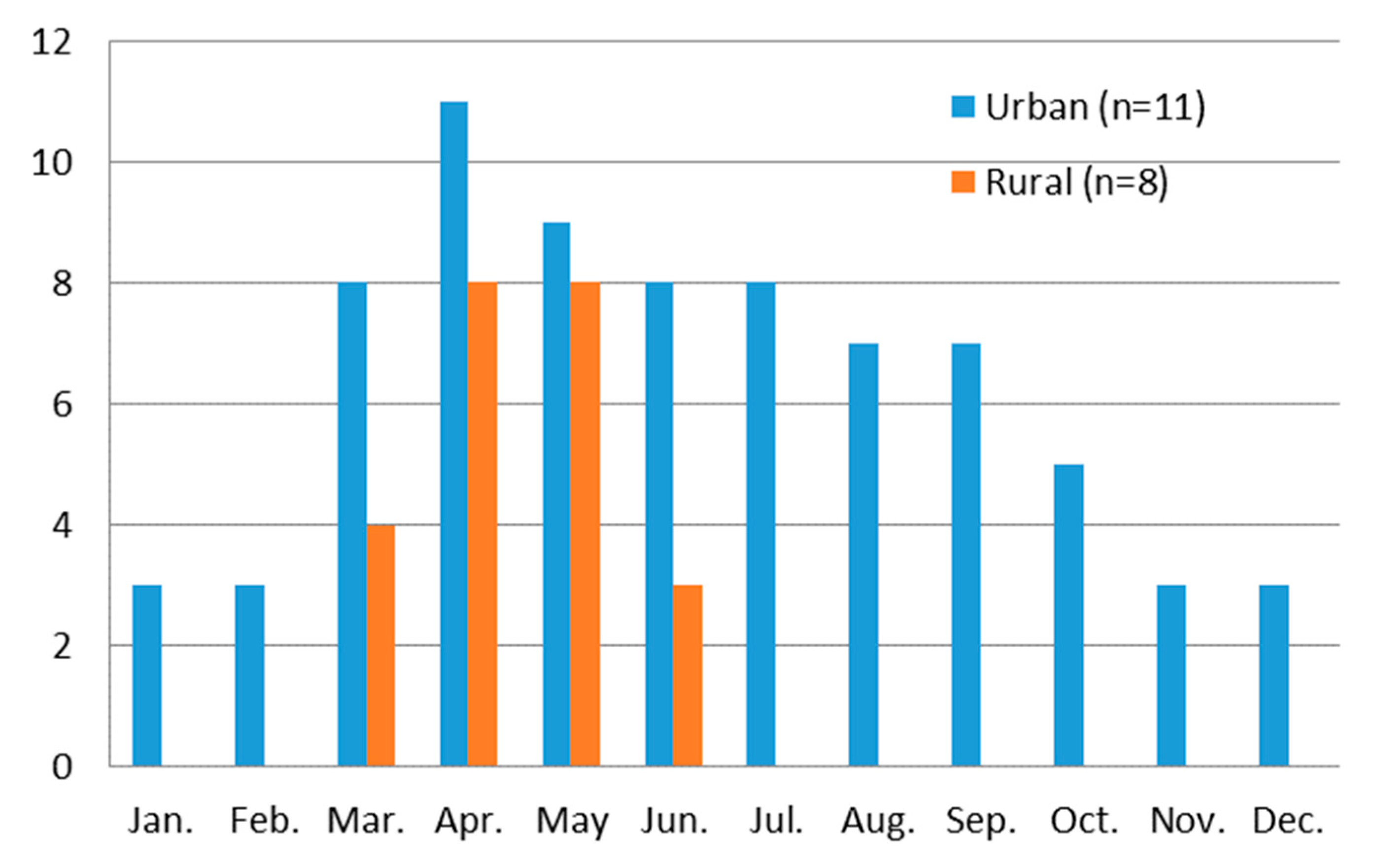

3.4. AC Use

3.5. Alternative Methods of Cooling

3.6. Energy Saving

3.7. Purchase of Electric Appliances

3.8. Future Prospects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Household | Gender of Respondents | Age of Respondents | Monthly Income (THB) | No. of Household Members | Household Members’ relation to Respondents (age) | Education of Main Income Earners | Occupation of Main Income Earners | Location | TVs in Use | Air Conditioners in Use | Electric Fans in Use | Refrigerators in Use | Rice Cookers in Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 59 | 36,000 | 5 | Husband (60), daughter (22), son-in-law (24), grandchild (<1) | Upper secondary | Farmer (rice & veg.), representative to local council | San Sai | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | M | 34 | 28,000 | 3 | Wife (35), Son (7) | College/university | Government employee | San Sai | 2 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | M | 60 | 17,867 | 2 | Wife (58) | Elementary | Farmer (rice & veg.) | San Sai | 1 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | M | 54 | 54,700 | 4 | Wife (48), son (27), son (24) | Upper secondary | Farmer (rice & veg.), grocery store owner | San Sai | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | M | 58 | 42,000 | 4 | wife (56), daughter (30), grandchild (7) | Elementary | Farmer (rice & veg.), general work | San Sai | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | M | 50 | 175,000 | 6 | Wife (47), father (79), son (25), daughter-in-law (26), grandchild (7) | Upper secondary | Farmer (rice & veg.) | San Sai | 3 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | M | 68 | 3600 | 2 | Wife (58) | Lower secondary | Hairdresser | San Sai | 1 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | F | 59 | 30,000 | 7 | Husband (59), daughter (35), daughter (30), grandchildren (8, 5, and <1) | Elementary | Farmer (rice & veg.) | San Sai | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | F | 64 | 16,200 | 6 | Husband (66), daughter (44), son-in-law (52), grandchildren (21 and 18) | Elementary | Grocery store | San Sai | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | M | 56 | 123,600 | 3 | Wife (53), brother or relative (61) | Elementary | Trading, handicraft | San Sai | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | M | 62 | 21,200 | 2 | Husband (65) | No formal education | Farmer (rice & veg.) | Mae Kao Tom | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 12 | F | 54 | 13,000 | 5 | daughter (32), grandchildren (13, 10, and <1) | Lower secondary | Hairdresser, computer assembly | Mae Kao Tom | 5 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 1 |

| 13 | M | 57 | 55,000 | 6 | Wife (58), daughter (31), son-in-law (28), grandchildren (9 and 2) | Elementary | Farmer (rice & veg.), assistant to a village head | Mae Kao Tom | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 14 | F | 65 | 3600 | 1 | - | Elementary | Rice mill | Mae Kao Tom | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 15 | M | 73 | 23,700 | 4 | Daughter (43), son-in-law (43), grandchildren (20, 14) | Vocational | Mechanic, farmer (rice) | Mae Kao Tom | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | M | 55 | 12,200 | 3 | Sister or relative (65), sister or relative (47) | Elementary | Hairdresser and farmer (frog) | Mae Kao Tom | 4 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| 17 | F | 54 | 15,000 | 4 | Husband (55), daughter (22), son-in-law (23) | Elementary | Driver | Mae Kao Tom | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 18 | M | 36 | 26,200 | 7 | Wife (30), child (4), nephew (21), niece (15), mother (63), father (63) | Upper secondary | Government employee, general work | Mae Kao Tom | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 19 | F | 57 | 12,000 | 2 | Husband (59) | Elementary | Farmer (rice), driver | Mae Kao Tom | 2 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| 20 | F | 29 | 62,000 | 5 | Father (60), mother (57), husband (33), son (1) | College/University | Nurse | Mae Kao Tom | 3 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 |

| Household | Gender of Respondents | Age of Respondents | Monthly Income (THB) | No. of Household Members | Household Members’ relation to Respondents (age) | Education Level of Main Income Earners | Occupation of Main Income Earners | House Type | ACs in Use | TVs in Use | Electric Fans in Use | Refrigerators in Use | Rice Cookers in Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 27 | 30,000 | 2 | Sister (30) | Master | Government employee | Two-story detached house | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | F | 50 | 80,000 | 2 | Husband (53) | Bachelor | Government officer | One-story detached house | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | F | 36 | 152,000 | 2 | Husband (69) | Bachelor | Retired/consultant/organic farmer | One-story detached house | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | F | 44 | 84,000 | 3 | Husband (46), daughter (9) | Bachelor | Teacher/music tutor | Two-story detached house | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | M | 36 | 105,000 | 4 | Wife (30), son (<1), mother-in- law (55) | PhD | Teacher | One-story detached house | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | F | 31 | 55,000 | 2 | Roommate (31) | Master | Teacher/selling daily commodities | Two-story row/shop house | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | M | 28 | 25,000 | 1 | None | Vocational | Bakery shop owner | Two-story row/shop house | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | F | 45 | 39,000 | 4 | Niece (29), son (21), daughter (9) | Master | Government officer | Two-story row/shop house | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | F | 36 | 50,000 | 2 | Roommate (28) | PhD | Teacher | Two-story detached house | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | M | 65 | 50,000 | 1 | None | Bachelor | Retired/missionary | Condo | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | F | 67 | 90,000 | 2 | Husband (70) | PhD | Teacher | Two-story detached house with guest house | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 |

| 12 | F | 51 | 83,000 | 4 | None (live away from family for work) | PhD | Teacher | Condo | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2017. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2017 (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Sahakian, M. Keeping Cool in Southeast Asia: Energy Consumption and Urban Air-Conditioning; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). The Future of Cooling in Southeast Asia 2019. Available online: http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/The_Future_of_Cooling_in_Southeast_Asia.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Japan Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Industry Association. Estimation of Global Air Conditioner Demand, 2019 (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.jraia.or.jp/download/pdf/we2019.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- The MECON Project. Effective Energy Efficiency: Policy Implementation Targeting “New Modern Energy CONsumers” in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Available online: http://meconproject.com/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Piyasil, P. Deliverable Report for MECON Project, Household Energy Efficiency: A Socio-Economic Perspective in Thailand. Available online: http://www.meconproject.com/wp-content/uploads/report/[Task%203-Household%20energy%20efficiency]%20Thailand%20country%20report.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Novianto, D.; Gao, W.; Kuroki, S. Review on People’s Lifestyle and Energy Consumption of Asian Communities: Case Study of Indonesia, Thailand, and China. Energy Power Eng. 2015, 7, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hori, S.; Kondo, K.; Nogata, D.; Ben, H. The determinants of household energy-saving behavior: Survey and comparison in five major Asian cities. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakoshi, C.; Nakagami, H.; Xuan, J.; Takayama, A.; Takaguchi, H. State of Residential Energy Consumption in Southeast Asia: Need to Promote Smart Appliances Because Urban Household Consumption Is Higher than Some Developed Countries. European Council for an Energy efficient economy Summer Study proceedings 2017. Available online: https://www.eceee.org/library/conference_proceedings/eceee_Summer_Studies/2017/7-appliances-products-lighting-and-ict/state-of-residential-energy-consumption-in-southeast-asia-need-to-promote-smart-appliances-because-urban-household-consumption-is-higher-than-some-developed-countries/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Mishra, A.; Ramgopal, M. Field studies on human thermal comfort—An overview. Build. Environ. 2013, 64, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.F.; Natalia, G.V.; Roberto, L. A review of human thermal comfort in the built environment. Energy Build. 2015, 105, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, F.; Nastasi, B. Energy Retrofitting Effects on the Energy Flexibility of Dwellings. Energies 2019, 12, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haldi, F.; Robinson, D. Adaptive actions on shading devices in response to local visual stimuli. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2010, 3, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, G.Y.; Steemers, K. Behavioural, physical and socio-economic factors in household cooling energy consumption. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Yan, D.; Wu, R.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, Y. Quantitative description and simulation of human behaviour in residential buildings. Build. Simul. 2012, 5, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.; Fabi, V.; Toftum, J.; Corgnati, S.; Olesen, B. Window opening behaviour modelled from measurements in Danish dwellings. Build. Environ. 2013, 69, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oca, S.; Hong, T.; Langevin, J. The human dimensions of energy use in buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jareemit, D.; Limmeechokchai, B. Understanding Resident’s Perception of Energy Saving Habits in Households in Bangkok. In 2017 International Conference on Alternative Energy in Developing Countries and Emerging Economies; Waewsak, J., Sangkharak, K., Othong, S., Gagnon, Y., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Jareemit, D.; Limmeechokchai, B. Impact of homeowner’s behaviours on residential energy consumption in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 21, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supasa, T.; Hsiau, S.-S.; Lin, S.-M.; Wongsapai, W.; Wu, J.-C. Household Energy Consumption Behaviour for Different Demographic Regions in Thailand from 2000 to 2010. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiang Mai University. Report of Thailand Household Energy Survey in Northern and Bangkok Metropolitan; unpublished. (In Thai)

- Han, J.; Yang, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Moschandreasb, D.J. A comparative analysis of urban and rural residential thermal comfort under natural ventilation environment. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Provincial Administration. Number of Citizens throughout the Kingdom according to the Civil Registration Evidence as of 31 December 2015 (In Thai). Available online: http://stat.bora.dopa.go.th/stat/pk/pk_58.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Thai Meteorological Department (TMD). Annual Weather Summary over Thailand in 2016. Available online: https://www.tmd.go.th/programs/uploads/yearlySummary/weather2016.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- National Statistics Office (NSO). Major Findings of the 2015 Household Energy Consumption. Available online: http://service.nso.go.th/nso/nsopublish/themes/files/EnergyPocket58.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Hachiya, Y.; Inoue, T. Housing in a Modern Farm Village in the Northeastern Part of the Kingdom of Thailand. Geijutsu Kogaku, J. Des. 2012, 16, 39–52. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Kondo, K.; Chutchaipolrut, A.; Arampongpun, S.; Kikusawa, I. Influence of Favorite Place in House—Outdoor or Indoor—On Energy Consumption and Happiness in Rural Thailand. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kubota, T.; Jeong, S.; Toe, D.; Ossen, D. Energy Consumption and Air-Conditioning Usage in Residential Buildings of Malaysia. J. Int. Dev. Coop. 2011, 17, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Leelakulthanit, O. Barriers and benefits of changing people’s behavior regarding energy saving of air conditioners at home. Asian Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rangsiraksa, P. Thermal comfort in Bangkok residential buildings. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture PLEA 2006, Geneva, Switzerland, 6–8 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karjalainen, S. Gender differences in thermal comfort and use of thermostats in everyday thermal environments. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Peer Review on Energy Efficiency in Thailand. Available online: https://aperc.ieej.or.jp/file/2010/9/26/PREE20100414_Thailand.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020).

| Section | Content |

|---|---|

| A. Household attributes | Number of household members, occupation(s) of main income earner, monthly income of main income earner, monthly income of household, education level of main income earner, type of dwelling, housing construction year, type of housing (owned/rented), number of rooms, electricity bill and energy consumption, other utility costs, energy/fuel for lighting and for cooking, hours spent at home |

| B. Ownership of electric appliances | Product type, number, size, power consumption, year of manufacture, hours in use |

| C. Use of air conditioners (ACs) | Reasons for purchasing new/additional AC units, usage period (heating and cooling function), hours in use, temperature setting, use of electric fan, cooling methods used besides AC or fan, satisfaction with use of AC |

| D. Intention/knowledge of reducing electricity consumption | Intention to reduce consumption of electricity, reason for saving electricity, recognition of energy label information |

| E. Purchase of electric appliances | Place where electric appliances were purchased, method of payment, three important factors that influenced purchasing decisions |

| F. Future lifestyle prospects | Three electric appliances you want to buy in the future, barrier(s) to purchase, consideration of secondhand appliances, role models for an ideal lifestyle |

| Brand Name | Model Number | Number of Doors | Capacity | Power Consumption | Refrigerant | Age of Product (Years in Use) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAEWOO | DTR-1459B | 1 | 141 L | NA | R134a 85 g | (16) |

| SINGER | NA | 1 | NA | NA | R12 100 g | (13) |

| AJ | RE-50C | 1 | 48 L | 50 W | NA | NA |

| HITACHI | R-64S-1 | 1 | 181 L | NA | R134a 100 g | 8 |

| HITACHI | R-H200PA | 2 | 217.2 L | 72 W | R600a 100 g | <1 |

| HITACHI | R-13DP | 1 | 111 L | 66 W | NA | (10) |

| SHARP | SJ-C17S-SL | 2 | NA | 101 W | NA | (5) |

| TOSHIBA | GR-B177T | 1 | 183.23 L | NA | R134a 95 g | 3 |

| Mitsubishi | MR-595GY | 1 | NA | NA | NA | (21) |

| TOSHIBA | GR-160DC | 1 | NA | 94 W | R12 110 g | (35) |

| HITACHI | NA | 2 | 189.3 L | 155 W | R134a 95 g | (10) |

| National | NA | 1 | NA | NA | NA | (20) |

| SAMSUNG | RA19FA | 1 | 190 L | 70 W | R134a 130 g | 7 |

| Whirlpool | NA | 1 | 127.95 L | 90 W | NA | (19) |

| SINGER | JL-245 | 1 | 128 L | 165 W | R12 108 g | (20) |

| Mitsubishi | MR-18RAX-GY | 1 | 180 L | 59 W | HFC134a 90 g | (4) |

| TOSHIBA | GR-B1732 | 1 | 170 L | NA | R134a 80 g | 6 |

| TOSHIBA | GR-M26KPD | 2 | 235.8 L | 135 W | HFC134a 135 g | NA |

| SINGER | JL-256 | 1 | 156 L | 90 W | R12 120 g | (21) |

| TANIN | NA | 1 | NA | NA | NA | (20) |

| HITACHI | R-T190W | 2 | 189.3 L | 155 W | R134a 95 g | NA |

| TOSHIBA | NA | 1 | 125 L | 158.4 W | R12 135 g | 34 |

| Philips | NA | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Panasonic | NR-A13G1 | 1 | 138 L | 69 W | HFC134a 90 g | (10) |

| TOSHIBA | GR-B157T | 1 | 155.8 L | 71 W | R134a 95 g | 4 |

| TOSHIBA | GR-H20KPD | 2 | NA | 100 W | HFC134a 115 g | 15 |

| SHARP | SJ-149 | 1 | 139 L | 85 W | R12 90 g | NA |

| TANIN | TER-518 | 1 | 140 L | 162.8 W | R12 145 g | (30) |

| SANYO | SR-659 MX | 1 | 165 L | 90 W | R134a 100 g | 10 |

| Haier | HR-1015B S MS | 1 | 147 L | 100 W | R134a 90 g | 5 |

| TOSHIBA | GR-B175Z | 1 | 170 L | 70 W | R134a 80 g | 5 |

| SAMSUNG | RA19FA | 1 | 190 L | 70 W | R134a 130 g | (5) |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural (n = 14) | Urban (n = 12) | Rural (n = 14) | Urban (n = 12) | Rural (n = 13) | Urban (n = 12) | |

| Price | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Function | 2 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Electricity consumption | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Warranty | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Good looking/appearance | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Durability | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Brand name | 4 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| Appliance 1 | Appliance 2 | Appliance 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Washing machine | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| TV | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Electric fan | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Refrigerator | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Ceiling fan | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| AC | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Electric stove | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Home theater for music | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Food mixer | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| None | 7 | 13 | 16 |

| Appliance 1 | Appliance 2 | Appliance 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Oven | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| TV | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Clothes dryer | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Coffee maker | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Water heater | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Microwave | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Freezer | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Washing machine | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Baby monitor | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Water boiler | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| None | 3 | 6 | 6 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshida, A.; Manomivibool, P.; Tasaki, T.; Unroj, P. Qualitative Study on Electricity Consumption of Urban and Rural Households in Chiang Rai, Thailand, with a Focus on Ownership and Use of Air Conditioners. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145796

Yoshida A, Manomivibool P, Tasaki T, Unroj P. Qualitative Study on Electricity Consumption of Urban and Rural Households in Chiang Rai, Thailand, with a Focus on Ownership and Use of Air Conditioners. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145796

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshida, Aya, Panate Manomivibool, Tomohiro Tasaki, and Pattayaporn Unroj. 2020. "Qualitative Study on Electricity Consumption of Urban and Rural Households in Chiang Rai, Thailand, with a Focus on Ownership and Use of Air Conditioners" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145796

APA StyleYoshida, A., Manomivibool, P., Tasaki, T., & Unroj, P. (2020). Qualitative Study on Electricity Consumption of Urban and Rural Households in Chiang Rai, Thailand, with a Focus on Ownership and Use of Air Conditioners. Sustainability, 12(14), 5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145796