Industrial Heritage 2.0: Internet Presence and Development of the Electronic Commerce of Industrial Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To formulate a model to evaluate the content of websites belonging to the industrial tourism sector based on the following four categories: Information, communication, electronic commerce, and additional functions.

- To evaluate websites from a sample of establishments offering industrial tourism in Catalonia.

- To improve the online management of these types of establishments by offering practical recommendations for more effective communication with their publics through their websites.

2. Industrial Tourism

3. Methodology

3.1. Information (I)

3.2. Communication (C)

3.3. Electronic Commerce (EC)

3.4. Additional Functions (AF)

4. Results

4.1. Information Dimension

4.2. Communication Dimension

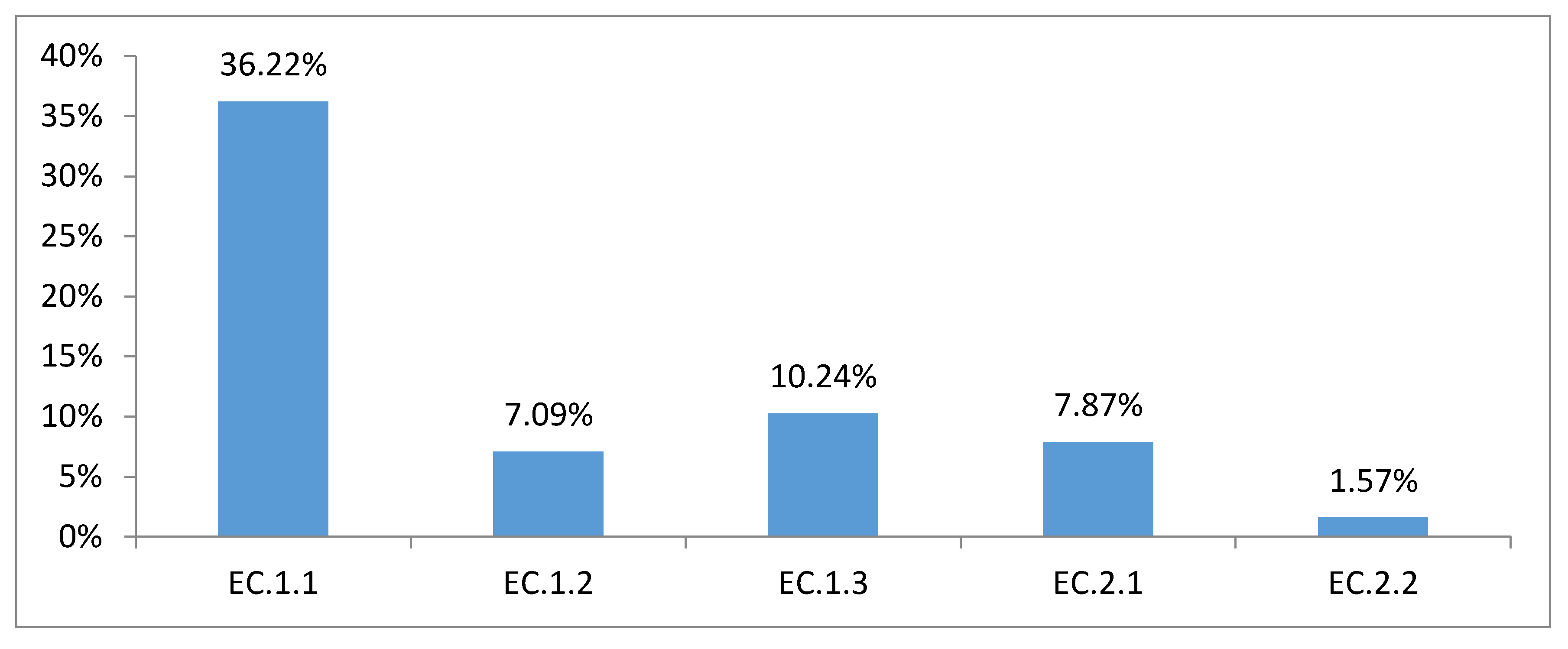

4.3. Electronic Commerce Dimension

4.4. Additional Functions (AF) Dimension

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Industrial Tourism Resources Analyzed

References

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A. Destination reputations and brands: Communication challenges. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Daries-Ramon, N. User-Generated Social Media Events in Tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Wang, Y.R. Key issues for ICT applications: Impacts and implications for hospitality operations. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2010, 2, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.-H.; Tzeng, G.-H. Exploring heritage tourism performance improvement for making sustainable development strategies using the hybrid-modified MADM model. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 921–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Mejia, M.D.L.Á.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamori, N.; Sun, J.; Zhang, S. The announcement effects of regional tourism industrial policy: The case of the Hainan international tourism island policy in China. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Zulaica, A. Redefiniendo el concepto de Turismo Industrial. Comparativa de la terminología en la literatura castellana, francesa y anglosajona. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2017, 15, 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- del Águila Obra, A.R.; Moreno, A.G.; Meléndez, A.P. Creación de valor online y redes sociales en el contexto del turismo cultural: El caso de los museos. Estud. Turísticos 2010, 185, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Daries-Ramon, N.; Mariné-Roig, E.; Martin-Fuentes, E. Implementation of Web 2.0 in the snow tourism industry: Analysis of the online presence and e-commerce of ski resorts. Spanish J. Mark. ESIC 2017, 21, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M. A review of innovation research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Hernández-Soriano, F.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Daries, N. Exploring service quality among online sharing economy platforms from an online media perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalicic, L.; Önder, I. Residents’ involvement in urban tourism planning: Opportunities from a smart city perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briciu, A.; Briciu, V.-A.; Kavoura, A. Evaluating How ‘Smart’Brașov, Romania Can Be Virtually via a Mobile Application for Cultural Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfetto, M.C.; Vargas-Sánchez, A. Towards a Smart Tourism Business Ecosystem based on Industrial Heritage: Research perspectives from the mining region of Rio Tinto, Spain. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat Forga, J.M.; Canoves Valiente, G. Cultural change and industrial heritage tourism: Material heritage of the industries of food and beverage in Catalonia (Spain). J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2017, 15, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempa, M.; Bujok, P.; Porzer, M.; Skupien, P. Industrial complexes and their role in industrial tourism–example of conversion. Geosci. Eng. 2016, 62, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiok, P.; Rodrigez, M.A.; Klempa, M.; Ielinek, Y.; Porzer, M. Industrial tourism and the sustainability of the development of tourism business. Tour. Educ. Stud. Pract. 2014, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsillo, N. On the Concept of Cultural Landscape and Methods for Protectings Ostrava s Post–Industrial Mining Cultural Landscape. Sborník příspěvků z mezinárodního kolokvia a Odb. Semin. TECHNÉ OSTRAVA 2007, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter, G.C.; Sperlich, T.; Worts, D.; Rivard, R.; Teather, L. Fostering cultures of sustainability through community-engaged museums: The history and re-emergence of ecomuseums in Canada and the USA. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, F.; De Crescenzo, V. Ecomuseums (on clean energy), cycle tourism and civic crowdfunding: A new match for sustainability? Sustainability 2018, 10, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.S.; Lee, S.Y. Smart ecomuseum app for efficient management of local resources. Int. J. Multimed. Ubiquitous Eng. 2014, 9, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Daries, N.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Marine-Roig, E. Maturity and development of high-quality restaurant websites: A comparison of Michelin-starred restaurants in France, Italy and Spain. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Qi, S.; Buhalis, D. Progress in tourism management: A review of website evaluation in tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, W.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Perng, C. A strategic framework for website evaluation based on a review of the literature from 1995–2006. Inf. Manag. 2010, 47, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González López, Ó.R.; Bañegil Palacios, T.M.; Buenadicha Mateos, M. El Índice Cuantitativo De Calidad Web Como Instrumento Objetivo De Medición De La Calidad De Sitios Web Corporativos/Quantitative Web Quality Index: An Objective Approach To Website Quality Assessment. Investig. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empres. 2013, 19, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, R.; Rocha, T.; Martins, J.; Branco, F.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Evaluation of e-commerce websites accessibility and usability: An e-commerce platform analysis with the inclusion of blind users. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2018, 17, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. Content analysis and thematic analysis. In Advanced Research Methods for Applied Psychology; Brough, P., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 211–223. ISBN 9781138698895. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez Diaz, Y. La Orientación al Mercado en el Sector Turístico con el uso de las Herramientas de la Web Social, Efectos en los Resultados Empresariales. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10902/5018 (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Bingley, S.; Burgess, S.; Sellitto, C.; Cox, C.; Buultjens, J. A classification scheme for analysing Web 2.0 tourism websites. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2010, 11, 281. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, T.; Law, R. Developing a performance indicator for hotel websites. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 22, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. An evaluation of Spanish hotel websites: Informational vs. relational strategies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Morrison, A.M. A comparative study of web site performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2010, 1, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schegg, R.; Steiner, T.; Frey, S.; Murphy, J. Benchmarks of web site design and marketing by Swiss hotels. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2002, 5, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; To, P.-L.; Shih, M.-L. Website practices: A comparison between the top 1000 companies in the US and Taiwan. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2006, 26, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Cantallops, A.S.; dos Santos, C.P. The characteristics of hotel websites and their implications for website effectiveness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, L.; Faré, M.; Inversini, A.; Passini, V. Hotel websites and booking engines: A challenging relationship. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2011; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, R. Five year longitudinal study of Australian winery websites. In Proceedings of the 13th Asia Pacific Management Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 18–20 November 2007; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2007; pp. 1429–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze, N.; Hu, Q. The evolution of corporate web presence: A longitudinal study of large American companies. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2006, 26, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, A.; Marine-Roig, E. Destination brand communication through the social media: What contents trigger most reactions of users? In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. Exploiting web 2.0 for new service development: Findings and implications from the Greek tourism industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walcott, P.A. Evaluating the readiness of e-commerce websites. Int. J. Comput. 2007, 4, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Marine-Roig, E. Diverse and emotional: Facebook content strategies by Spanish hotels. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Marine-Roig, E. Do Hotels Talk on Facebook About Themselves or About Their Destinations? In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 344–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, P.-H.; Wang, S.-T.; Bau, D.-Y.; Chiang, M.-L. Website evaluation of the top 100 hotels using advanced content analysis and eMICA model. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Chung, N.; Lee, C.; Preis, M.W. Motivations and use context in mobile tourism shopping: Applying contingency and task–technology fit theories. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Barcala, M.; González-Díaz, M.; Prieto-Rodríguez, J. Hotel quality appraisal on the Internet: A market for lemons? Tour. Econ. 2010, 16, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimon, F.; Vidgen, R.; Barnes, S.; Cristóbal, E. Purchasing behaviour in an online supermarket: The applicability of ES-QUAL. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 52, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondović, B.; Djuričković, T.; Kašćelan, L. Drivers of E-business diffusion in tourism: A decision tree approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F. E-WOM and Accommodation: An Analysis of the Factors That Influence Travelers’ Adoption of Information from Online Reviews. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.E.; Clarke, T.B.; Spekman, R.E. The emergence and impact of consumer brand empowerment in online social networks: A proposed ontology. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E.; Fernandez, C.; Mateu, C.; Marine-Roig, E. Modelling a grading scheme for peer-to-peer accommodation: Stars for Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E.; Mateu, C.; Fernández, C. Are users’ ratings on Tripadvisor similar to hotel categories in Europe? Cuad. Tur. 2018, 42, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busalim, A.H.; Che Hussin, A.R.; Iahad, N.A. Factors Influencing Customer Engagement in Social Commerce Websites: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Montegut-Salla, Y.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Daries, N. Rural cooperatives in the digital age: An analysis of the Internet presence and degree of maturity of agri-food cooperatives’e-commerce. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daries-Ramon, N.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Mariné-Roig, E. Deployment of Restaurants Websites’ Marketing Features: The Case of Spanish Michelin-Starred Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 20, 249–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, W.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Perng, C. A strategic website evaluation of online travel agencies. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Gretzel, U. Perceptions of museum podcast tours: Effects of consumer innovativeness, Internet familiarity and podcasting affinity on performance expectancies. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Tourist Movement on Borders Survey Frontur 2019. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 1 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SEGITTUR Estudio de Mercado de Apps Turísticas. Available online: www.segittur.es (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Nogueira Cortimiglia, M.; Ghezzi, A.; Renga, F. Social Applications: Revenue Models, Delivery Channels, and Critical Success Factors—An Exploratory Study and Evidence from the Spanish-Speaking Market. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2011, 6, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cole, D. Exploring the sustainability of mining heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Definition | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Information | This dimension assesses the information available on the websites of industrial tourism establishments and ease of finding it. | [25,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] |

| Communication | This dimension measures the website’s capacity to interact with customers, either through communication mechanisms, Web 2.0 resources or the availability of information in different languages. | [25,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] |

| Electronic commerce | This dimension assesses the website’s capacity to conduct secure commercial activities. | [25,29,32,33,34,36,37,45] |

| Additional functions | This dimension measures the website’s capacity to convey security through data protection elements and certifications and the use of new media such as the mobile version of the website or its applications. | [29,38,42,45,46] |

| Categories | Items |

|---|---|

| 1. Information | I.1.1. Description of location (which economic activity it belongs to, address, origin, history, etc.) |

| I.1.2. Location images | |

| I.1.3. Visual information regarding visits: duration, price, whether guided or not, etc. | |

| I.1.4. Communication of news or events | |

| I.1.5. Links to websites evaluating tourist services (Booking, Trivago, Tripadvisor, etc.) | |

| I.1.6. Schedules for visits, opening times, vacation schedule | |

| 2. Facilities and services | I.2.1. Information regarding the area to be visited |

| I.2.2. Information on how to get there (maps or Google maps) | |

| I.2.3. Information on the processes involved in carrying out the economic activity | |

| I.2.4. Information on the different operational areas of the company | |

| I.2.5. Information regarding the final distribution channels | |

| 3. Environment | I.3.1. Links to different tourism information websites for nearby areas |

| I.3.2. Links to other businesses related to the economic activity | |

| 4. Promotion | I.4.1. Promotion of events, advertisements, etc. |

| I.4.2. Economic incentives: vouchers, coupons, discounts (for groups, for example), exclusive offers, product promotions, etc. |

| Categories | Items |

|---|---|

| 1. Interaction with customers | C.1.1. Contact: telephone, fax, e-mail |

| C.1.2. Possibility of receiving comments online | |

| C.1.3. Instant messaging | |

| C.1.4. Online surveys | |

| C.1.5. Frequently asked questions section (FAQs) | |

| C.1.6. Section to subscribe to the newsletter and offers (Newsletter) | |

| C.1.7. Customer registration area | |

| C.1.8. Possibility for customers to vote on services received and visits made | |

| 2. Resources Web 2.0 | C.2.1. Content syndication (RSS) |

| C.2.2. Podcast/Vodcast | |

| C.2.3. Applications that allow the user to publish content | |

| C.2.4. Possibility for customers to share content (retweet, share, etc.) | |

| C.2.5. Link to Twitter | |

| C.2.6. Link to company blog | |

| C.2.7. Links to external image and video platforms (YouTube, Flickr, Instagram, Pinterest, etc.) | |

| C.2.8. Links to company’s social networks (Facebook, Linkedln, Google+, etc.) | |

| C.2.9. Link to Wikipedia | |

| C.2.10. Other 2.0 platforms (Technorati, Netvibes, etc.) | |

| 3. Language capabilities | C.3. Website available in more than two languages (Catalan, Spanish and a third language) |

| Categories | Items |

|---|---|

| Reservation services | EC.1.1. Possibility of making a reservation online |

| EC.1.2. Discount vouchers | |

| Pay online | EC.2.1. Possibility of paying online |

| EC.2.2. Guarantees of secure payment |

| Categories | Items |

|---|---|

| 1. Data security | AF.1.1. Privacy policy or legal notice |

| AF.1.2. Data Protection Act | |

| 2. Certifications | AF.2.1. ISO9000 or EFQM quality certificates |

| AF.2.2. Q Quality Tourism Certification | |

| AF.2.3. Environmental certifications (ISO14000 or EMAS) | |

| AF.2.4. Other certifications (SICTED, D.O., etc.) | |

| 3. Mobile version | AF.3.1. Web link to website’s mobile version |

| AF.3.2. Availability of apps |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Daries, N.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Montegut-Salla, Y. Industrial Heritage 2.0: Internet Presence and Development of the Electronic Commerce of Industrial Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155965

Cristobal-Fransi E, Daries N, Martin-Fuentes E, Montegut-Salla Y. Industrial Heritage 2.0: Internet Presence and Development of the Electronic Commerce of Industrial Tourism. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155965

Chicago/Turabian StyleCristobal-Fransi, Eduard, Natalia Daries, Eva Martin-Fuentes, and Yolanda Montegut-Salla. 2020. "Industrial Heritage 2.0: Internet Presence and Development of the Electronic Commerce of Industrial Tourism" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155965

APA StyleCristobal-Fransi, E., Daries, N., Martin-Fuentes, E., & Montegut-Salla, Y. (2020). Industrial Heritage 2.0: Internet Presence and Development of the Electronic Commerce of Industrial Tourism. Sustainability, 12(15), 5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155965