Green Human Resource Management: An Evidence-Based Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art on GHRM

1.2. Aims of This Systematic Review

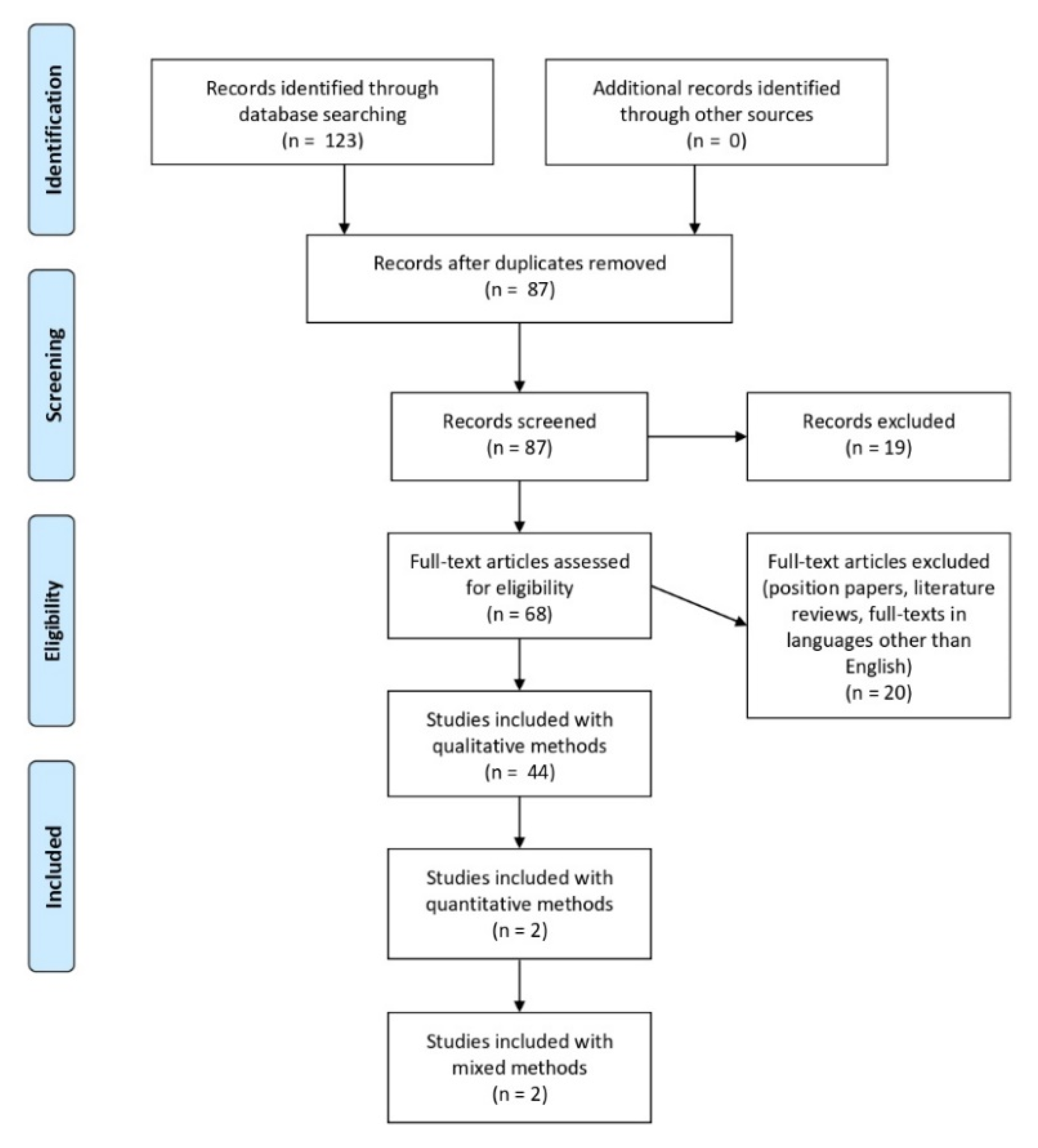

2. Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

- (green or environmental or sustainable) and (“human resources” or “human resource management” or HRM).

2.2. Data Collection Process

2.3. Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

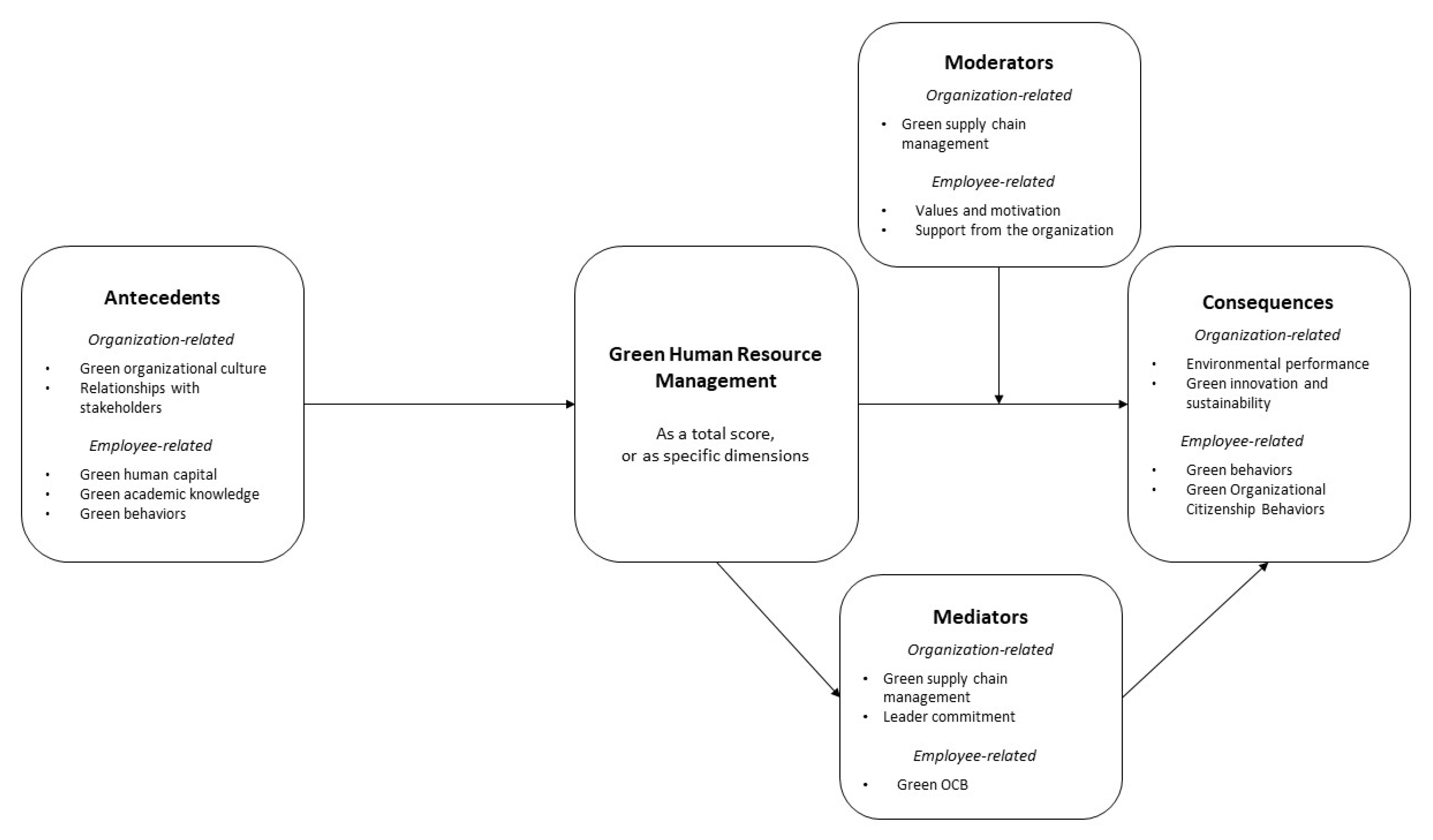

3.2. Synthesis of Results

3.2.1. Conceptualizations of GHRM

3.2.2. Organizational and Employee-Related Antecedents of GHRM

3.2.3. GHRM Consequences on Organizations

3.2.4. GHRM Consequences on Employees

4. Discussion

4.1. Chronological and Geographical Trends

4.2. Dimensions of the GHRM Construct

4.3. GHRM Organizational Outcomes

5. Main Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Our Common Future: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmeyer, W. Greening People: Human Resources and Environmental Management; Wehrmeyer, W., Ed.; Greenleaf: Sheffield, UK, 1996; ISBN 1874719152. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benn, S.; Dunphy, D.; Griffiths, A. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability, 3rd ed.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781315819181. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M. European corporate sustainability framework for managing complexity and corporate transformation. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2003, 5, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, C.L.Z.; Dubois, D.A. Strategic HRM as social design for environmental sustainability in organization. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.M.; Lawrence, G.A. Agripolitical Organizations in Environmental Governance: Representing Farmer Interests in Regional Partnerships. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, K.A.; Nyborg, K. Attracting responsible employees: Green production as labor market screening. Resour. Energy Econ. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Montanari, F.; Scapolan, A.; Epifanio, A. Green and nongreen recruitment practices for attracting job applicants: Exploring independent and interactive effects. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, G.; Mzoughi, N.; Pekovic, S. Green not (only) for profit: An empirical examination of the effect of environmentalrelated standards on employees’ recruitment. Resour. Energy Econ. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhwar, P.S.; Sparrow, P.R. An integrative framework for understanding crossnational human resource management practices. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donohue, W.; Torugsa, N.A. The moderating effect of ‘Green’ HRM on the association between proactive environmental management and financial performance in small firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.J.; White, K.M. A Tale of Two Theories: A Critical Comparison of Identity Theory with Social Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Brooks-Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg, M.; Pringle, C.D. The Missing Opportunity in Organizational Research: Some Implications for a Theory of Work Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, C.; Lochan Dhar, R. Green competencies: Construct development and measurement validation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, V.N.; Geetha, S.N. A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Turner, J.C. Intergroup behaviour, self-stereotyping and the salience of social categories. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ ecofriendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; MullerCamen, M. Stateoftheart and future directions for green human resource management. Ger. J. Res. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J.P.; Jacob, J. A Study of Green HR Practices and Its Effective Implementation in the Organization: A Review. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opatha, H.H.D.N.P.; Arulrajah, A.A. Green Human Resource Management: Simplified General Reflections. Int. Bus. Res. 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Green Human Resource Management: Policies and practices. Cogent. Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.A.; Opatha, H.H.D.N.P.; Nawaratne, N.N.J. Green human resource management practices: A review. Sri Lankan J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Jan, F.A.; Ahmad, M.S. Green employee empowerment: A systematic literature review on stateofart in green human resource management. Qual. Quant. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; MullerCamen, M.; Redman, T.; Wilkinson, A. Contemporary developments in Green (environmental) HRM scholarship. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green HRM: A review, process model, and research agenda. Univ. Sheff. Manag. Sch. Discuss. Pap. 2008, 1, 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Shahriari, B.; Hassanpoor, A.; Navehebrahim, A.; Jafarinia, S. A systematic review of green human resource1 management. Environ. Prot. 2019, 7, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, J.Y.; MohdYusoff, Y. Studying the influence of strategic human resource competencies on the adoption of green human resource management practices. Ind. Commer. Train. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kerdawy, M.M.A. The Role of Corporate Support for Employee Volunteering in Strengthening the Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Corporate Social Responsibility in the Egyptian Firms. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixedmethods study. Tour. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee Green Behavior: A Theoretical Framework, Multilevel Review, and Future Research Agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.; Teixeira, A.A.; Freitas, W.R.S. Environmental development in Brazilian companies: The role of human resource management. Environ. Dev. 2012, 3, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Fawehinmi, O. Nexus between green intellectual capital and green human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Redman, T. Progressing in the change journey towards sustainability in healthcare: The role of “Green” HRM. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Translating stakeholder pressures into environmental performance—the mediating role of green HRM practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Rabiei, S.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Envisioning the invisible: Understanding the synergy between green human resource management and green supply chain management in manufacturing firms in Iran in light of the moderating effect of employees’ resistance to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VidalSalazar, M.D.; CordónPozo, E.; FerrónVilchez, V. Human resource management and developing proactive environmental strategies: The influence of environmental training and organizational learning. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S.; Jiang, K. An Aspirational Framework for Strategic Human Resource Management. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.Y.; Cao, Y.; Mughal, Y.H.; Kundi, G.M.; Mughal, M.H.; Ramayah, T. Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anwar, N.; Nik Mahmood, N.H.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Noor Faezah, J.; Khalid, W. Green Human Resource Management for organisational citizenship behaviour towards the environment and environmental performance on a university campus. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Jantan, A.H.; Yusoff, Y.M.; Chong, C.W.; Hossain, M.S. Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) Practices and Millennial Employees’ Turnover Intentions in Tourism Industry in Malaysia: Moderating Role of Work Environment. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Vo Thanh, T.; Tučková, Z.; Thuy, V.T.N. The role of green human resource management in driving hotel’s environmental performance: Interaction and mediation analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HaddockMillar, J.; Sanyal, C.; MüllerCamen, M. Green human resource management: A comparative qualitative case study of a United States multinational corporation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Mohd Yusoff, Y. Green human resource management: A twostudy investigation of antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Manpow. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Norazmi, N.A.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Fernando, Y.; Fawehinmi, O.; Seles, B.M.R.P. Top management commitment, corporate social responsibility and green human resource management: A Malaysian study. Benchmarking 2019, 26, 2051–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; FazalEHasan, S.M.; Kaleem, A. How ethical leadership stimulates academics’ retention in universities: The mediating role of jobrelated affective wellbeing. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 1348–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtembu, V. Does having knowledge of green human resource management practices influence its implementation within organizations? Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2019, 17, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, Q. The Era of Environmental Sustainability: Ensuring That Sustainability Stands on Human Resource Management. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjarwati, T.; Budiarti, E.; Audah, A.K.; Khouri, S.; Rębilas, R. The impact of green human resource management to gain enterprise sustainability. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 20, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H.; Xu, H. Effects of green human resource management and managerial environmental concern on green innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D.; Guerci, M. Deploying Environmental Management Across Functions: The Relationship Between Green Human Resource Management and Green Supply Chain Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1081–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.M.; Talib Bon, A. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Effects of Green HRM and CEO ethical leadership on organizations’ environmental performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Chong, T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organisational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamola, P.; Bangwal, D.; Tiwari, P. Green HRM, worklife and environment performance. Int. J. Environ. Work. Employ. 2017, 4, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance: An EmployeeLevel Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. The role of environmental uncertainty, green HRM and green SCM in influencing organization’s energy efficacy and environmental performance. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2020, 10, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, H.A.; Jaaron, A.A.M. Assessing green human resources management practices in Palestinian manufacturing context: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.C.; Unsworth, K.L.; Russell, S.V.; Galvan, J.J. Can green behaviors really be increased for all employees? Tradeoffs for “deep greens” in a goaloriented green human resource management intervention. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management and Employee Green Behavior: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Mohamad, Z.; Noor Faezah, J.; Muhammad, Z. Assessing the green behaviour of academics: The role of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Int. J. Manpow. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.; Kinnie, N.; Hutchinson, S.; Rayton, B.; Swart, J. Understanding the People and Performance Link: Unlocking the Black Box; CIPD Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- HowardGrenville, J.A. Inside the “black box”: How organizational culture and subcultures inform interpretations and actions on environmental issues. Organ. Environ. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Paper Characteristics | Study Characteristics | Participant Characteristics | GHRM Construct and Role | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Country | Study Methodology | Organization (Type) | Participants | GHRM Dimensions Included | GHRM as Mediator or Moderator | |

| Carmona-Moreno | 2012 | Spain | Quantitative | Chemical firms | M | ns | Mediator |

| Jabbour | 2012 | Brazil | Quantitative | Automobile manufacturers | M | ns | |

| Vidal-Salazar et al. | 2012 | Spain | Quantitative | Hotels | M | Training | Mediator |

| Jabbour et al. | 2013 | Brazil | Quantitative | Automobile manufacturers | M | ns | |

| Paillè et al. | 2014 | China | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E + M | ns | |

| Pinzone et al. | 2016 | UK | Quantitative | Health services | E | Competence building, Performance management, Employee involvement. | |

| Guerci et al. | 2016 | Italy | Quantitative | Manufacturing and service firms | M | Hiring, Training and involvement, Performance management and compensation. | Mediator |

| O’Donohue et al. | 2016 | Australia | Quantitative | Machinery and equipment manufacturers | E | ns | Moderator |

| Haddock-Millar et al. | 2016 | UK, Germany, Sweden | Qualitative | Restaurant chain | E | ns | |

| Masri et al. | 2017 | Palestine | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E+M | Management of organizational culture, Performance management and appraisal, Recruitment and selection, Training and development, Employee empowerment and participation, Reward and compensation. | |

| Cheema et al. | 2017 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | M | ns | |

| Dumont et al. | 2017 | China | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | ns | |

| Nejati et al. | 2017 | Iran | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | Recruitment and selection, Training and development, Employee empowerment, Pay and reward, Performance management and appraisal. | |

| Chamola et al. | 2017 | India | Quantitative | Energy provider firms | E | Training and development, Pay and reward * | |

| Zaid et al. | 2018 | Palestine | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | Hiring, Training and involvement, Performance management and compensation | |

| Longoni et al. | 2018 | Italy | Quantitative | Manufacturing and service firms | E | Hiring, Training and involvement, Performance management and compensation * | |

| Shen et al. | 2018 | China | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | ns | |

| Saeed et al. | 2019 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | Recruitment and selection, Training and development, Employee empowerment, Pay and reward, Performance management and appraisal. | |

| Rawashdeh | 2018 | Jordania | Quantitative | Health services | M | Recruitment and selection, Training and development, Rewards. | |

| Yusliza et al. | 2019 | Malaysia | Quantitative | Manufacturing and service firms | M | Analysis and job description, Performance, Recruitment, Rewards, Selection, Training. | |

| Yong et al. | 2019 | Malaysia | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | Analysis and job description, Performance, Recruitment, Rewards, Selection, Training. | |

| Roscoe et al. | 2019 | China | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | Analysis and job description, Performance, Recruitment, Rewards, Selection, Training * | |

| Ahmad et al. | 2019 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Health services | E+M | Involvement, Pay and reward, Performance management, Training, Recruitment and selection * | Mediator |

| Moktadir et al. | 2019 | Bangladesh | Qualitative | Tannery industry | M | ns | |

| Yong et al. | 2019 | Malaysia | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | ns | |

| Mtembu | 2019 | South Africa | Mixed methods | University Campus | acHR | ns | |

| Andjarwati et al. | 2019 | Indonesia | Quantitative | Mining sector | E | ns | |

| Kim et al. | 2019 | Thailand | Quantitative | Hotels | E | ns | |

| Agyabeng-mensah et al. | 2019 | China | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | ns | |

| Davis et al. | 2020 | UK | Quantitative | Automobile manufacturers | E | ns | |

| Pham et al. a | 2019 | Vietnam | Mixed methods | Hotels | E | ns | |

| Al Kerdawy | 2019 | Egypt | Quantitative | Manufacturing and service firms | M | Staffing, Training, Performance appraisal, Reward and recognition * | |

| Pham et al. b | 2019 | Vietnam | Quantitative | Hotels | E | Training, Performance management, Employee involvement. | |

| Singh et al. | 2020 | UAE | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | Ability (Recruitment, Training), Motivation (Performance, Rewards), Opportunity (Employee Involvement). | Mediator |

| Malik et al. | 2020 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Manufacturing firms | E | Analysis and job description, Performance, Recruitment, Rewards, Selection, Training. | |

| Anwar et al. | 2020 | Malaysia | Quantitative | University Campus | E | Competence (Recruitment, Training), Motivation (Performance, Rewards), Employee involvement. | |

| Shafaei et al. | 2020 | Malaysia | Quantitative | Hotels | E | ns | |

| Iqbal | 2020 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Banking sector | E | ns | Mediator |

| Yu et al. | 2020 | China | Quantitative | Automobile manufacturers | E | ns | |

| Lee | 2020 | Kazakistan | Quantitative | E | ns | ||

| Ren et al. | 2020 | China | Quantitative | Chemical firms | M | ns | |

| Song et al. | 2020 | China | Quantitative | Industries | E | ns | |

| Fawehinmi et al. | 2020 | Malaysia | Quantitative | University Campus | E | ns | |

| Hameed et al. | 2020 | Pakistan | Quantitative | E+M | ns | ||

| Zhao et al. | 2020 | China | Quantitative | Industries | E | Recruitment and selection, Training, Performance management, Compensation, Involvement * | Mediator |

| Islam et al. | 2020 | Malaysia | Quantitative | Hotels | E | Recruitment and selection, Training, Performance management, Pay and reward, Involvement. | |

| Chaudhary | 2020 | India | Quantitative | Automobile manufacturers | E | Recruitment and selection, Training, Performance management, Pay and reward, Involvement * | |

| Huo et al. | 2020 | China | Quantitative | Coal enterprises | E | Training, Recruitment, Staffing, Compensation, Performance management, Involvement * | Mediator |

| AMO Approach Construct | Description | GHRM Dimensions | Number of Papers Mentioning the Dimension | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability | Identifying and applying employee green competencies | Analysis and job description | 4 | |

| Selection, recruitment, and hiring | 20 | |||

| Training and development | 23 | |||

| Motivation | Creating an appraisal and reward system that reinforces green behaviors | Performance management, Performance appraisal, | 20 | |

| Rewards, pay, and compensation | 20 | |||

| Opportunity | Offering the opportunity to be proactive in the crafting of activities aimed at increasing green behaviors | Involvement and empowerment | 15 |

| Authors | Year | Studies Addressing GHRM Antecedents | Studies Addressing GHRM Consequences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee-Related Antecedents | Organization-Related Antecedents | Employee-Related Consequences | Organization-Related Consequences | Mediators | Moderators | ||

| Carmona-Moreno | 2012 | Environmental management | Organizational sustainability | ||||

| Jabbour | 2012 | Green management practices | |||||

| VidalSalazar et al. | 2012 | Organizational innovativeness | Proactive green strategies | ||||

| Jabbour et al. | 2013 | ||||||

| Paillè et al. | 2014 | Environmental performance | Green OCB | ||||

| Pinzone et al. | 2016 | Green OCB (all GHRM dimensions) | Environmental commitment (Employee involvement) | Affective commitment | |||

| Guerci et al. | 2016 | Environmental pressure by clients and stakeholders | Environmental performance (Training and involvement, Performance management and compensation) | ||||

| O’Donohue et al. | 2016 | Proactive environmental management | Environmental performance | ||||

| HaddockMillar et al. | 2016 | Organizational culture and implementation strategies | |||||

| Masri et al. | 2017 | Environmental performance | correlational analyses only | ||||

| Cheema et al. | 2017 | Corporate social responsibility | Sustainable environment | ||||

| Dumont et al. | 2017 | Green behavior | Green climate | ||||

| Nejati et al. | 2017 | Green supply chain management (Training and development, Employee empowerment, Pay and reward) | Resistance to change (negative) | ||||

| Chamola et al. | 2017 | Environmental performance | Employee motivation to show green behaviors at work | ||||

| Zaid et al. | 2018 | Environmental performance | Green supply chain management | ||||

| Longoni et al. | 2018 | Environmental performance, Financial performance | Green supply chain management | ||||

| Shen et al. | 2018 | Performance, Turnover intentions, OCB | Perceived organizational support | ||||

| Saeed et al. | 2019 | Green behavior (all GHRM dimensions) | Environmental knowledge | ||||

| Rawashdeh | 2018 | Environmental performance | correlational analyses only | ||||

| Yusliza et al. | 2019 | Top management commitment (all GHRM dimensions) and green supply chain management (Analysis and job description) | |||||

| Yong et al. | 2019 | Organizational sustainability (Recruitment and Training) | |||||

| Roscoe et al. | 2019 | Environmental performance | Leadership emphasis, message credibility, peer involvement, and employee empowerment | ||||

| Ahmad et al. | 2019 | Ethical leadership | Job satisfaction | ||||

| Moktadir et al. | 2019 | Green selection and recruiting processes, Green organizational culture, Green purchasing, Top management commitment | |||||

| Yong et al. | 2019 | Green human capital | Green relational capital | ||||

| Mtembu | 2019 | Green academic knowledge | Green organizational policies | ||||

| Andjarwati et al. | 2019 | Green behavior | Environmental performance | Employee personal values | |||

| Kim et al. | 2019 | Organizational commitment, Green behavior | Environmental performance | ||||

| Agyabengmensah et al. | 2019 | Organizational performance | |||||

| Davis et al. | 2020 | Green behavior | Motivation | ||||

| Pham et al. a | 2019 | Green behavior | Green performance management, Green employee involvement | ||||

| Al Kerdawy | 2019 | Corporate social responsibility | Corporate support for employee volunteering | ||||

| Pham et al. b | 2019 | Green commitment (Training and Performance management) | Green OCB | ||||

| Singh et al. | 2020 | Green transformational leadership | Green innovation (Ability, Motivation, and Opportunity) | ||||

| Malik et al. | 2020 | Organizational sustainability (Recruitment and selection, Rewards) | |||||

| Anwar et al. | 2020 | Environmental performance (Competence and Motivation) | Green OCB | ||||

| Shafaei et al. | 2020 | Organizational culture | Job satisfaction | Environmental performance | Employee meaning of work | ||

| Iqbal | 2020 | Employees’ green behavior | Organizational sustainability | ||||

| Yu et al. | 2020 | Environmental cooperation with customers and suppliers | Green supply chain management | ||||

| Lee | 2020 | Environmental performance, Energy efficiency | |||||

| Ren et al. | 2020 | Environmental performance | Top management team commitment | ||||

| Song et al. | 2020 | Green innovation | Green human capital | ||||

| Fawehinmi et al. | 2020 | Green behavior | Environmental knowledge | ||||

| Hameed et al. | 2020 | Green OCB | Green empowerment, Personal values | ||||

| Zhao et al. | 2020 | Environmental strategies, discretionary slack | Environmental reputation | ||||

| Islam et al. | 2020 | Turnover intentions (Involvement, Pay and reward) | |||||

| Chaudhary | 2020 | Green behavior | Organizational identification | ||||

| Huo et al. | 2020 | Organizational commitment towards HRM | Green-related creativity | ||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benevene, P.; Buonomo, I. Green Human Resource Management: An Evidence-Based Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155974

Benevene P, Buonomo I. Green Human Resource Management: An Evidence-Based Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):5974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155974

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenevene, Paula, and Ilaria Buonomo. 2020. "Green Human Resource Management: An Evidence-Based Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 5974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155974

APA StyleBenevene, P., & Buonomo, I. (2020). Green Human Resource Management: An Evidence-Based Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 12(15), 5974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155974